Chapter 5 - The ageing/disability interface

Introduction

5.1

This chapter will focus on the interface between disability services

provided under the CSTDA and aged care services.

5.2

Australia's demographic trend is towards an ageing population. By

2044-45 one-quarter of Australians will be aged 65 years or more, approximately

double the present proportion. This is expected to have broad implications for

social and economic policy and government spending. Aged care has been

recognised as the most demographically sensitive area of government spending

and the number of people requiring aged care services is expected to increase.[1]

There will also be significant implications for people with disabilities.

People with disabilities, because of improvements in care and support, are

living longer and increasingly also require aged care services. People with

disabilities can also need aged care services earlier in life as a consequence

of living with a disability or due to shorter than average life expectancy.

5.3

There are also workforce and social implications for disability services

as the proportion of population aged over 65 increases. The available workforce

in the health, community services and disability areas is likely to decrease while

demand for services will increase. Informal carers will also be under

increasing pressure as they age and will be caring for a greater number of

older people as well as people with disabilities.

5.4

Given these trends the interface between disability services funded

under the CSTDA and aged care services will be important. In 2005 the Senate Community

Affairs References Committee Report, Quality and Equity in Aged Care,

recommended that the Commonwealth 'address the need for improved service

linkages between aged care and disability services'.[2]

While disability services and aged care services can often provide similar

types of services to clients, disability services are generally not well equipped

to manage the conditions and symptoms of ageing, and aged care services are

generally not able to meet the specific support needs of people with disability.

Disability and ageing

5.5

The relationship between disability and ageing is complex. While the

prevalence of disability increases steadily from around 35 years of age, the needs

of people with disabilities and the types of disabilities acquired vary as they

age.[3]

The most frequently reported primary disability for users of CSTDA funded

services in all age groups from 5–14 years to 45–64 years was intellectual

disability. In contrast the most commonly reported disability for users aged 65

years and over was physical.[4]

People over 65 with a disability needed more frequent assistance and with more

core activities than younger people. This appears particularly true for people

with intellectual disabilities as they get older.[5]

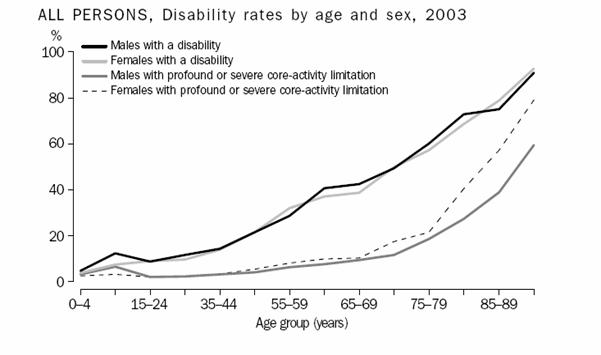

Figure 5.1

Source: ABS, Disability Ageing and Carers, 2003, p. 5.

People with a disability who are ageing

5.6

The exact number of people with disabilities who also require aged care

services is not certain. Dr J Torr commented:

One thing to recognise is that we are not talking about a huge

population. Even though there are projections for the rapid increase of that

population, it is still going to be a small population compared with, say, the

general population and the explosion in the number of people with dementia.[6]

5.7

The AIHW report, Disability support services 2004-05, reported there

were 2,819 persons aged over 65 in CSTDA funded supported accommodation. While

not all these people would require or seek access to additional support for

needs associated with ageing, people with disability can require ageing related

support before they reach 65. In the AIHW report there are 11,229 people listed

in supported accommodation aged 45 to 65.[7]

5.8

The AIHW report Disability and Ageing identified a number of

groups at risk of falling within the 'grey areas' of the disability and aged care

services interface and potentially not being able to access appropriate

services.

- People with an early onset disability often have fewer basic

living skills and so need higher levels of assistance in these areas as they

age.

- People ageing with a disability acquired during adulthood usually

have basic living skills. Their need for assistance generally arises from

increasing physical frailty and diminishing levels of functional skills.

- Some people ageing with an intellectual disability may acquire

dementia relatively early in life, at around age 50. They may become frail and

need health and medical care more than help with other activities. These people

may be more appropriately assisted by aged care services, because of their

early ageing and deteriorating health.

- People retiring from Commonwealth-funded employment services may

need replacement services.

- People accessing CSTDA accommodation support may require more

flexible 'retirement' services, enabling them to 'age in place' or to make a

smooth transition to appropriate residential aged care.[8]

5.9

The AIHW noted that because of their changing needs, or changes in their

eligibility for certain services, it may be appropriate or necessary for people

ageing with a disability to transfer between service types – for instance from

specialist disability to generic aged care services. This transition is most

likely to affect people with an early onset disability in their later years.[9]

5.10

People with a lifelong disability who are ageing have different needs

from older people who have not aged with a lifelong disability. Associate Professor

Christine Bigby in her submission to the Committee stated:

Although a diverse group, people ageing with a life long

disability share some common characteristics associated with their pattern of

ageing and the impact of their life experiences of being a person with a

disability that suggest they should be regarded as a distinct special group of

older people, who cannot simply merge into the general aged population. For

example, some groups of people with life long disability age relatively early,

experience additional health needs or impairments associated either with ageing

per se or with their original impairment. For some their age related health

needs are a complex combination of disability and age related changes.[10]

5.11

People with a disability who are ageing are not a homogenous group and there

is no single factor such as age, the age disability is acquired or the type of

acquired disability which will reliably indicate their needs as they age. This

is important as it highlights the importance of tailoring services to the needs

of each person and the need for services and programs to work across

jurisdictional boundaries to meet these individual needs and circumstances.[11]

Jurisdictional overlap and inefficiency

5.12

The disability services provided under the CSTDA and aged care services

can differ in a number of ways. These include the focus of their programs, the

types of services offered, the main target groups and the expertise of

personnel providing the services. While aged care services focus more on health

needs, broad personal care and self-maintenance, disability support services

emphasise non-health needs and can address a broader range of needs, including

employment.[12]

5.13

The difficult nature of the interface between CSTDA and aged care

services was discussed in the AIHW's evaluation of the Innovative Aged Care Interface

Pilot.

Community aged care programs act on the disability sector by

blocking access to community-based aged care specific services for CSTDA

consumers in supported accommodation. Correspondingly, the disability sector

acts on the aged care sector by steering disability services clients who are

ageing and younger clients with complex needs that cannot be managed at home

towards residential aged care. A number of complex issues lie hidden in this

simplistic appraisal of the situation.

There is considerable overlap between the type of basic living

support that supported accommodation providers deliver to CSTDA consumers and

the types of assistance delivered to older people through community aged care

programs. Older people with disabilities and people with disabilities who age

prematurely typically experience an increase in support needs that is

associated with ageing. Much of the additional need that emerges falls into the

areas of personal assistance, domestic assistance and social support— all types

of assistance which is presumed to be provided by the person’s supported

accommodation service. An important question is what level of service a

supported accommodation service is funded to deliver and whether the level of

funding is designed to meet the lifelong needs of each resident.[13]

5.14

Many of the interface problems appear to stem from the access and

eligibility requirements of disability services and aged care services. The CSTDA

does not impose explicit age-based restrictions on eligibility for services,

however the current CSTDA defines 'people with disabilities' as those with

disabilities which manifest before the age of 65 and in practice services are

generally directed to people under 65 years of age.[14]

5.15

ACROD commented:

The needs that arise from ageing do not displace the needs

associated with a long-term disability: they are additional. Yet the existing

funding arrangements and policy rules mostly deny a person simultaneous access

to services from the aged care and disability service systems.[15]

Aged care services

5.16

The main aged care services funded by government in Australia are

residential services, community care services, respite services and assessment

services. These include the Home and Community Care (HACC) program, the Aged

Care Assessment Program, Community Aged Care Packages (CACPs), the Extended

Aged Care at Home (EACH) program and the National Respite for Carers Program

(NRCP).

5.17

Several other programs address the special needs of aged care including

various programs for people with dementia and their carers, the Veterans' Home

Care (VHC), the Veterans' Home Nursing Program, the Day Therapy Centre Program,

the Continence Aids Assistance Scheme, and flexible aged care services through Multipurpose

Services and services under the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Aged

Care Strategy.[16]

Home and Community Care (HACC)

Program

5.18

Home and Community Care (HACC) Program provides services for older

people, people with disability, and their carers. HACC services include

community nursing, domestic assistance, personal care, meals on wheels and

day-centre based meals, home modification and maintenance, transport and

community-based respite care (mostly day care).[17]

The HACC program is aimed at reducing inappropriate or premature admission to

residential care by providing basic maintenance and support services to frail

older people and people with a disability.

5.19

Commonwealth, State and Territory governments jointly fund the HACC

program, with the Commonwealth contributing approximately 60.8 per cent and

State and Territory governments funding the remainder. Total national

expenditure on the Home and Community Care (HACC) program was $1.3 billion in

2004-05.[18]

In 2004-05, HACC services provided care and assistance to over 744,000 people,

36,800 more than in 2003-04. People with disability are estimated to comprise

over 24 per cent of the total number of HACC clients but consume an estimated

30 per cent of the funding. This is because proportionally people with

disabilities access higher levels of services.[19]

5.20

Nominally HACC services are delivered on the basis of a person’s need

for assistance and not on the basis of age. An estimated 68.2 per cent of HACC

clients in 2004-05 were aged 70 years or over. However CSTDA clients who reside

in supported accommodation facilities are normally excluded from accessing HACC

services. People with disabilities (including CSTDA service users) who live in

private residences, or another form of accommodation besides disability-funded

supported accommodation, form part of the HACC target population and may be

eligible to receive HACC services.[20]

5.21

Access to HACC services is governed by the HACC National Program

Guidelines (2002), which provides:

The HACC Program does not generally provide services to

residents of aged care homes or to recipients of disability program

accommodation support service, when the aged care home/service provider is

receiving government funding for that purpose. Nor does it generally serve

residents of a retirement village or special accommodation/group home when a

resident’s contract includes these services...

The excluded services, also known as 'out of scope', are classed

as such because funding is already provided for them through other government

programs.

Excluded services are: accommodation (including rehousing,

supported accommodation, and aged care homes or a related service)...[21]

5.22

In general all services provided by supported accommodation services

under State and Territory government disability programs are regarded as ‘a related

service’. This eligibility barrier exists so that HACC services would not be

provided where services would be funded under another government program such

as the CSTDA, or in other words to prevent 'double dipping' (the receipt of

substitutable services from multiple program sources of funding).[22]

5.23

A number of submissions and witnesses raised the issue of the

bureaucratic boundaries between the disability and HACC services and the

problems caused. For example Associate Professor Christine Bigby stated:

What is happening is that people are living in shared supported

accommodation funded by disability services, and the Commonwealth funded aged

care services or HACC services are saying, "We can't provide top-up

support, we can’t provide expertise, we can't provide in-home nursing, because

otherwise that would be double dipping".[23]

5.24

Ms Raelene West commented:

Continuing to be problematic is the interface between the CSTDA

and HACC funding arrangements...The shortfall in disability services resources

however has seen many people with disabilities being forced to utilise HACC

services to make up the need for services they require to live independently

within the community. In many cases, as the Young People in Nursing Homes

campaign has shown, many people with disabilities are being forced into

institutional facilities because of limited or no other accommodation options

available. The use of HACC funding to provide disability services therefore

provides a messy interface between Commonwealth HACC funding and

State/Territory funded disability services.[24]

Aged Care Assessment Program

5.25

The objective of the Aged Care Assessment Program is to assess the needs

of frail older people and their eligibility to access available care services

appropriate to their care needs. This is largely through Aged Care Assessment

Teams (ACATs). In general ACATs have access to a range of skills and expertise

and are able to comprehensively assess older people taking account of the restorative,

physical, medical, psychological, cultural and social dimensions of their care

needs. ACATs involve clients, their carers, and service providers in the assessment

and care planning process. A key feature of the ACAT process is face-to-face

assessment. While ACATs can refer to a variety of services, including HACC

services, their assessment is mandatory for access to Commonwealth funded residential

aged care (permanent or respite) as well as some community and flexible care.

5.26

The Committee received evidence that ACATs were not sensitive to

requirements of people with disability who also required care for needs

associated with ageing. For example Dr Jennifer Torr commented:

The average age for someone with Down syndrome to develop

Alzheimer's disease is around 50. In a shared supported accommodation house, if

the carers in that house approach the aged-care assessment services or teams,

they are routinely told that the person is under 65. If you ring up and say you

want to receive services, the first thing they do is get the person’s name,

address and date of birth. If they are under 65, they say, 'They’re under 65.'

You say, 'Yes, but they’ve got Down syndrome.' The reply is, 'We don’t see

people with intellectual disabilities.' That is fair enough. It is not the role

of the aged-care assessment teams to do assessments for someone who is under 65

with an intellectual disability. However, this is for someone who has an age

related disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, which is a progressive and currently

terminal condition. When that is pointed out to them the next thing they say

is, ‘But we don’t put young people into nursing homes.[25]

Community Aged Care Packages

5.27

Community Aged Care Packages (CACPs) provide an alternative home-based

service for elderly people who an ACAT assesses as eligible for care similar to

low level residential care. The program provides individually tailored packages

of care services that are planned and managed by an approved provider.

5.28

CSTDA clients in supported accommodation are also not normally eligible

to receive a CACP. Provisions that allow younger people with disabilities to be

considered for a CACP do not apply in the case of those who live in supported

accommodation settings.[26]

An older person with a disability who resides in supported accommodation would

also not be able to access assistance through a CACP. The guidelines provide

that people who live in supported accommodation facilities and receive funding through

government programs to provide services similar to CACPs, or where lease

arrangements include the provision of similar services, are not eligible to receive

CACPs. While it appears some scope exists for CACPs to co-exist with disability

services, the 'governing principle is that people are not receiving the same

services from different sources at the same time'.[27]

Extended Aged Care at Home (EACH)

program

5.29

The EACH program provides tailored and managed packages of care, including

nursing care or personal assistance, targeted at the frail aged and who have care

needs equivalent to a high level of residential care. The Aged Care Assessment

and Approval Guidelines note that it should be 'extremely rare' for an ACAT to approve

a younger person for an EACH package. The guidelines state that:

These packages are intended to be provided to frail older

Australians. Disability programs managed by state and territory governments are

the main providers of services to assist younger people with disabilities to

remain at home.[28]

Residential aged care

5.30

Residential aged care is intended for frail older people whose overall

care support needs cannot be adequately met in the general community, even with

HACC services, CACPs or EACH packages. Residential aged care comprises

accommodation plus care services within the accommodation setting (for example,

nursing care, personal care, meals and laundry). A person approved for

residential aged care by an Aged Care Assessment Team is approved for either

residential respite care or low level or high level permanent residential care.

5.31

A person with a disability who would not be classed as an aged person

may still be eligible for residential aged care if there are no other care facilities

more appropriate to meet the person's needs. In the past residential aged care

has been the main type of aged care service to be accessed by people with

disabilities who live in CSTDA-funded accommodation facilities because this

group is not ordinarily entitled to access community aged care programs funded

by the Commonwealth. For a person with a disability, transferring to a

residential aged care service can mean losing their existing specialist

disability services.[29]

5.32

There were also indications that some younger people with a disability were

being disadvantaged by recent policy decisions to divert them from accessing

residential aged care. Dr Flett of the Brightwater Care Group commented:

...the gate-keeping, if you like, for entry into nursing homes and

hostels now is being quite scrupulously applied—for very good reasons—to

preserve aged care beds for aged people, but it means that where a person might

have been able to enter a nursing home in the past they cannot now. And so they

are sitting in hospitals or in other services for a much longer time, because

the queue is a whole lot longer.[30]

Young people in aged care

5.33

In June 2004 there were 6,240 clients aged under 65 years in permanent

residential aged care, representing 4.3 per cent of all residents. Of these

clients, 987 (16 per cent) were aged under 50 years.[31]

There has been recent concern about the significant number of young people with

disability in residential aged care. Such an environment is generally

considered inappropriate for younger people (with the average age of residents

being 84 years on entry to care) and is a 'last resort'. In the Quality and

equity in aged care report this Committee found the situation of younger

people in residential aged care facilities 'unacceptable in most instances' and

it recommended that individual situations be assessed and alternative

accommodation be provided.[32]

5.34

In February 2006, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) announced

joint funding of $244 million over five years for a programme aimed at reducing

the number of younger people with disability in residential aged care. This program

will initially target people aged under 50 years and people will only be moved

to alternative, more appropriate services if they wish to do so.

Impacts of the aged care/disability

interface

5.35

A number of submissions regarding the aged care/ disability interface

outlined problems relating to the availability of aged care services when

people reach the age of 65. Other submissions highlighted what they perceived

as an unfair difference in the availability of aged care services for people

who were disabled. Dr Morkham of the YPINH Alliance commented:

We have a very fragmented system at the moment. It is divided

according to age, not need. The quite extraordinary situation exists where you

are considered young and disabled until you are 65, whereupon your disability

magically disappears and you are simply old. This means that you lose some of

the valuable disability supports and services, if you can get them, that you may

need to continue beyond 65.[33]

5.36

The lack of clarity of the interface between disability and aged care

services also appears to be creating additional burdens for service providers. Ms

Armstrong of Endeavour commented:

We are currently finding that one of our levels of frustration

is our ability to work with all levels of government to successfully pilot our

way through the ageing issue and to develop seamless transitions between the

different services required by people, regardless of the jurisdiction and

funding body. The organisation strongly supports the principle of ageing in

place. It is one of the key challenges that we are facing. Cross-jurisdictional

issues between Commonwealth and state funding and program bodies impact upon Endeavour’s

ability to successfully and adequately acquire funding and supports, as well as

to undertake transitional planning for service users wanting to retire from

Commonwealth business services, where they live in state funded, non-vocational

services.[34]

5.37

There were also concerns expressed regarding the lack of uniformity and

consistency of assessment procedures for access to disability services and aged

care services. Carers Australia commented:

People over 65 years with disabilities are also accessing

CSTDA-funded services. As a consequence of these situations, many carers are

interacting with service providers from CSTDA, HACC and NRCP funded services. A

common eligibility assessment tool would remove the need for many carers and

the person for whom they care to undergo multiple assessments to achieve the

mix of services required. Often assessment is required by different service

areas within the same agency or provider.[35]

Innovative Pool Aged Care

Disability Interface Pilot

5.38

The Disability Aged Care Interface Pilot was established under the Aged

Care Innovative Pool, an initiative of the Department of Health and Ageing.

Through the Pilot, a pool of flexible care places was made available outside

the annual Aged Care Approvals Rounds to trial new approaches to aged care for

specific population groups. This Pilot was aimed at people with aged care needs

who live in supported accommodation facilities funded under the CSTDA and who

were at risk of entering residential aged care. The objective was to test

whether these people have aged care needs distinct from their disability needs

and whether the provision of aged care services in addition to disability

services could reduce inappropriate admissions to residential aged care.[36]

The Pilot delivered additional services, tailored to individual needs, which

are aged care specific, to assist clients remain in their current CSTDA funded

living situations for as long as possible. Nine Pilot projects commenced

operation between November 2003 and December 2004. The Department of Health and

Ageing has agreed to continue to fund clients already in the pilots, but not to

admit new entrants or to expand the pilots into a program.

5.39

An AIHW evaluation of the Pilot identified a number of benefits for the

individuals involved and the service delivery systems. It indicated that

'additional assistance delivered with an aged care focus has significantly

improved the quality of life of individual clients and that these improvements

are likely to have long-term benefits for individuals and service systems'. The

evaluation participants received was a median of approximately 6 additional

hours of assistance in addition to aged care planning and ancillary services.[37]

Comprehensive and collaborative joint assessments involving aged care providers

and disability sector providers resulted in very few inappropriate referrals.

5.40

However, the AIHW evaluation also identified issues with the provision

of aged care services to people with disabilities, including difficulties in

assessing what were aged care specific needs and what was to be considered expenditure

on aged care.

Perhaps the greatest conundrum for evaluation is the contrast

between seven projects operating separate aged care and disability budgets and

two, Ageing In Place and MS Changing Needs, that operate with aged care

services fully integrated into the disability accommodation service using

pooled aged care and disability budgets. To some extent the latter two projects

were able to provide a more seamless service, but there were indications that

pooled funding and full integration made the reporting of aged care specific

expenditure more difficult...

From a system-wide perspective the top-up model of aged care

funding seems to be an incomplete solution to the problem of limited choice in

community-based aged care for people with disabilities in supported

accommodation. It helps in individual cases by patching over systemic problems

at the interface of disability and aged care programs and at the interfaces

between different types of specialist disability services. There is a risk that

some groups will fall through gaps in services modelled on separate aged care

and disability funding. The high degree of overlap between the types of

assistance delivered by Pilot projects and those funded under the CSTDA means

that criteria are required to establish how aged care funding is to be used.

The Pilot has shown that individual care planning will tend to address areas of

need that are implicated in an individual’s risk of entry to residential aged

care and that these areas are closely related to features of the disability

support system.

The evaluation concludes that eligibility criteria based on

interpretations of aged care specific need or age-related need, which have been

demonstrated to vary, may lead to program management rules such as those which

currently prevent access to HACC-funded services for the target group. Using

subjective eligibility criteria, the only way to avoid questions of ‘double

dipping’ and ‘cost shifting’ is for program managers to trust the processes

that determine eligibility for aged care. There is also the unresolved issue of

people with disabilities aged over a certain age, say 60 or 65 years, who live

in supported accommodation and whose risk of admission to residential aged care

is assessed as mainly disability related. The needs of these older Australians

are not addressed by the evaluated model. [38]

Support for the Pilot

5.41

A number of submissions expressed support for the Pilot and various

'top-up' or blended funding arrangements as a possible solution to problems

with the disability/aged care interface. Associate Professor Bigby commented on

the success of the Pilots:

They demonstrated that there can be partnerships between

disability workers in the disability system and in the aged care system. With a

fraction of extra funds you can resource the people who are in the shared

supported accommodation—the staff—to respond appropriately and to add to their

knowledge and their ability to respond to people’s age related health care

needs in particular. They demonstrated that you can share staff, you can

resource staff or you can employ specialist staff—that the agencies can work

together. They were very successful in improving the quality of life of all the

residents in those houses where people were ageing, and they demonstrated that people

could be retained and age in place. They also showed that the amount of top-up

that was necessary was significantly less, I think, than a full package.

...they are people with a disability who are being compensated for

that disability and they are also people who are ageing and are entitled to

support from the aged care system. I do not think they are double dipping, but

they certainly do not need twice as much. You need to look at it that way. In

terms of the shared arrangement between the Commonwealth and the state, the

state pays the same and the Commonwealth pays a fraction of what it would pay

if the costs were transferred completely. And that is what is happening at the

moment: there is a cost shift going on between the states and the Commonwealth.[39]

5.42

ACROD argued in their submission that:

The principle of 'top up' funding (with clients of disability

service programs entitled to attract Commonwealth Aged Care funding) should be

more widely applied in recognition of the fact that the needs that arise from

ageing are additional to those associated with a long-term disability.[40]

5.43

This argument was repeated by Aged and Community Services Australia,

which did not regard the concerns in relation to distinguishing disability and

aged care needs as significant:

This principle of blended funding, enabling services and support

for those care needs related to disability and those to ageing, needs to be

able to be applied throughout the system...

However, the Department of Health & Ageing, while committing

to continued funding for existing clients, will not continue the program or

make these services available as a mainstream, rather than pilot, program. The

main issue appears to be the need to determine which supports are required as a

result of the disability a person may have and which, and how much, relate to

the persons ageing. This is a prime example of concerns about cost shifting

between jurisdictions getting in the way of effective service delivery to

clients. A practical way of determining, or approximating, this needs to be

developed or it will be used as a reason for not being able to combine funds

and create service responses which genuinely meet the needs of this population.[41]

5.44

However, the Commonwealth saw the need for more work in determining the

most appropriate model to address the ageing needs of people with disability:

Preliminary results of the evaluation of these pilots by the

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare indicate that identifying ageing

related care needs of people already receiving disability services is complex.

Although the pilots enabled some useful insights, further work is needed to

inform any consideration by governments of how best to meet their needs.[42]

Ageing in place

5.45

An important component of aged care services is the principle of 'ageing

in place'. The concept of ageing in place was a key part of the Aged Care

Act 1997 which increased the opportunities for people to remain in

their home (however defined) regardless of their increasing care needs.[43]

Ageing in place as a policy was designed to enable residents to remain in the

same environment as their care needs increased, in facilities which could offer

appropriate accommodation and care. The advantages of ageing in place for the

elderly are significant and include less disruption to their lives and

continuity of care in a familiar environment.

5.46

Broad support was expressed for the right of people with disabilities to

'age in place' where they choose to do so.[44]

However, a part of the difficulty of the jurisdictional overlap and inefficiency

in the interface between aged care and disability services is the commitment to

allow people to age in place. If people with disability are to be allowed to

age in place then their aged care needs must be assessed and then aged care

services must provided to them as they age.

5.47

The Queensland Government proposed a clear division to provide clarity

regarding which level of government is responsible for people over 65 years of

age with a disability.

The Queensland Government considers that the Commonwealth

Government should take responsibility for those aged over 65 years, including

those who have a disability, while the Queensland Government should maintain

responsibility for those aged less than 65 years. To have clear policies in

this area would help to reduce the complexity surrounding the provision of

services to this cohort.[45]

5.48

However the Commonwealth noted this could be contrary to the principle

of allowing people with a disability the choice to age in place:

As a growing number of people with disability are living longer,

the principle of ‘ageing in place’ should apply to the disability community,

just as it does to the general community, so that people with disability are

encouraged to age in place and, where they choose to do so, are able to access appropriate

support services.

Suggestions have been made that the Australian Government should

take responsibility for older people with disability and that all their care

needs should be regarded as aged care needs.

Such suggestions would be at odds with 'ageing in place' and

conflict with responsibilities under the current CSTDA. In addition, as with

older people generally, not all people with disability who are ageing will

require aged care services (noting that the average age at entry into

residential aged care is 84 years). Continuity of their specialist disability

support services as they age will be essential.[46]

5.49

The Committee considers that people with disabilities should have the

option of ageing in place if they so desire. Funding arrangements and eligibility

criteria should not disallow people with disabilities in supported

accommodation from receiving aged care services. At the same time, the

Committee recognises that for some people with disabilities, an aged care

facility may offer the most appropriate accommodation setting given their

particular circumstances. In such cases, access to residential aged care

services should be made available even if the person is not over 65 years of

age

Recommendation 22

5.50

That funding arrangements and eligibility requirements should be made to

allow supplemental aged care services to be made available to people with

disabilities who are ageing, allowing them to age in place. Administrative funding

arrangements should not impede access to aged care services for people with a

disability who are ageing.

Interface with health care

5.51

People with disabilities have very diverse health needs and like the

rest of the population require access to health services. People with

disabilities experience poorer health outcomes compared to the general

population and can have significantly lower life expectancy as a result. The

Victorian Government commented:

Higher incidences of conditions such as

epilepsy, mental health disorders, vision and hearing impairments,

gastrointestinal conditions, obesity, osteoporosis and dental disease are

reported frequently. Additionally these health conditions are either poorly

recognised or inadequately managed by health professionals. Many of these

diseases and conditions are preventable or through earlier identification and

intervention the impact can be significantly decreased thereby reducing more

costly interventions.[47]

5.52

Strengthening 'access to generic services for people with disabilities'

was one of the strategic policy priorities in the current CSTDA. Access to

health care was identified as an issue for people with a disability. Associate

Professor Bigby commented:

There is also an assumption that, under the CSTDA, people with

disabilities have access to healthcare services. They are not funded through

the CSTDA, but it is assumed that, like everybody else, they have access to

good-quality medical services. It is very clear from the research both here and

overseas that people with disabilities, people with intellectual disabilities in

particular, have difficulty accessing high-quality medical care. Our generic

system is not attuned to dealing with people with complex needs associated with

disability. There are almost no specialist services for adults and older people

with lifelong disabilities that address their particular healthcare needs.[48]

5.53

Problems with access to generic health services were also identified by

the Disability Advocacy and Complaints Service of South Australia:

Women in wheelchairs still cannot be transferred onto

examination tables, many private practitioners and allied health services such

as chiropractors, do not provide wheelchair access. Private psychiatrists

refuse to treat people with intellectual disabilities and paranoid

schizophrenia.[49]

5.54

The role of disability service providers and health care was highlighted

by Dr Torr:

However state disability services do have a role to play in

health care of people with intellectual disabilities. As the providers of

supported accommodation and general care disability service providers have a

role to play in managing lifestyle risk factors. Disability workers are

expected to be able to identify when someone needs to access a health service,

arrange access, coordinate care, attend appointments, manage health information

and to follow through on recommendations. All of this is required of people who

are not health professionals.[50]

5.55

There is growing interest in the issue of health services for people

with disabilities, their health outcomes, access to services and the quality of

those services. Concerns which have been identified often relate to the

training and expertise of health professionals. These concerns include: problems

in communication between health professionals and people with disabilities;

health professionals' inadequate knowledge of health conditions of people with

disabilities, including patterns of dual diagnoses such as mental health and

intellectual disability; 'diagnostic overshadowing' when a person's symptoms or

condition is wrongly attributed to their disability rather than a separate

medical condition; and the need for health professions to ensure sexually

active people with disabilities are respected and given the 'appropriate

information and support to protect themselves'.

5.56

Other issues for people with disability and health services include: the

adequacy of medical records; the need for Medicare schedules to recognise that

some people with disabilities require longer consultations to ensure the

required communication takes place; the need for Auslan services; affordability

of equipment; medication labelling and instructions (a variety of formats are

needed); and the need for trials of new drugs to include a wider range of

people, including people with disabilities.[51]

Recommendation 23

5.57

Access to generic services should continue to be a priority for the next

CSTDA, particularly access to health care services.

Ageing informal carers

The importance of informal care

5.58

Family members shoulder the main responsibility of meeting the needs of

people with disabilities, providing unpaid care and assistance on a regular and

sustained basis. Of the 200,493 CSTDA service users during 2004-05, 84,964 (42

per cent) reported the existence of an informal carer. Of these 57,712 (68 per

cent) reported that this carer was their mother. The next most commonly

reported carer relationships were father (6.5 per cent), other female relative

(6.3 per cent), wife/female partner (4.6 per cent) and husband/male partner

(4.3 per cent).[52]

5.59

Trends towards deinstitutionalisation and non-institutionalisation mean

that greater numbers of people with disabilities now live in the community,

frequently with their families. In 2003, nearly 454,000 people aged 65 years

and over provided assistance to people with a disability. Around one-quarter of

these care providers (113,200) were a primary carer, that is, they provided the

most assistance to the care recipient. Overall, people aged 65 and over

accounted for 24 per cent of primary carers of people with a disability.[53]

37 per cent of primary carers spent on average 40 hours or more per week

providing care and 18 per cent spent 20 to 39 hours per week.[54]

5.60

The Committee's report Quality and equity in aged care recognised

the tragic challenges facing ageing carers.

Many ageing carers have provided care for family members for

years, if not decades. This length of caring takes its toll on ageing carers:

physically, financially, socially and emotionally. At a time when others have

enjoyed a long retirement, carers face the anxiety of what will happen to their

children once they require aged care.[55]

5.61

Evidence provided to the Committee again highlighted the problems facing

ageing carers, particularly parents who were caring for children with

disabilities. For example Ms Catherine Edwards, who cares for her son, commented:

Most people look forward to a day they can retire; go on

holidays and generally slow down a bit. When can carers look forward to

retirement?

With no security, my motivation is practically zilch and like

many others in similar situations, I see myself reaching crisis point sooner

than I technically would expect. I would dearly like to see my son settled into

supported accommodation where I can assist in the transition making it easier

for him, the staff and my family.[56]

He will be in his 30s when I am in my 60s. How will I manage? It

is not a luxury. It is not about families trying to renege on responsibilities.

It is about quality of life, not just for the person with a disability but for

the whole family. It is about choice for families. It is about being able to

choose when the time is right for the whole family to say, "We can't do

this anymore." This country needs a really good system of supported

accommodation for adults with a disability.

5.62

Submissions also made clear that the ageing population was placing

increasing pressures on carers. Carers Australia commented:

Many carers have dual caring roles. They care for a child with a

disability and care for a frail aged parent or a partner with a disability at

the same time. Many carers who have cared for a child with a disability for a

long time now require their own age care services.[57]

Transitional arrangements for ageing

carers

5.63

An ageing population means that an increasing number of unpaid carers

will require aged care services themselves and will no longer be able to act as

carers. The people with disability for whom they care will need to be

transitioned to alternative paid care. The uncertainty surrounding the issue of

future care was a critical issue for informal carers and people with

disabilities.

5.64

The AIHW study of unmet need in 2002 noted that disability services

packages and residential arrangements are most valued when they allow a carer

to begin withdrawing from the primary care role and assure carers regarding

future care arrangements. It noted that the fundamental questions facing ageing

carers are 'When can I retire?' and 'What will happen when I die?' [58]

It was suggested to the Committee that a wider range of options was needed to support

unpaid ageing family carers including in the transition arrangements involved with

relinquishing care. This would assist in providing unpaid family carers with

greater certainty in planning for the future. Ms Estelle Shields commented:

I would also like to see a recommended age, possibly 30 or 35

for the disabled person or 65 for the primary carers, whereupon the family was

offered (but not compelled to accept) an appropriate residential setting for

their family member.[59]

5.65

Ms Deidre Croft made a similar argument highlighting the need to address

the uncertainty for family carers:

Basically they want to have an assurance that, when they

indicate that they can no longer provide the care that is required for their

son or daughter, there will be an alternative available...

One of the concerns that I have,

particularly with regard to people with a lifelong disability, is that the

assumption is that parents will make a lifelong commitment. If you do not have

an end point, you cannot pitch yourself or pace yourself over a time frame. So

parent carers want some assurance that this is the extent of the commitment.

Given that we define ‘youth’ these days normally as up to 25 years of age, I

think that at 25 years of age an adult with a disability, even if it is an

intellectual disability, should have the opportunity to leave the family home...

If a family carer knew: "When my son or daughter turns 20 I

have given my life, I have done my all; I do not have to break my back anymore,"

I think that would sustain people. It would give them a sense of hope that they

can go the distance, whereas now people have no hope, they look at an

indefinite future.[60]

Respite for ageing carers

5.66

In the 2004-05 Budget, the Commonwealth announced that it would provide

$72.5 million over four years from 2004-05 to 2007-08, to increase access to

respite care for older parents caring for their sons and daughters with a

disability. Under this measure, parents aged 70 years and over who provide

primary care for a son or daughter with a disability will be entitled to up to

four weeks respite care a year. Parent carers aged between 65 and 69 who

themselves need to be hospitalised will be entitled to up to two weeks respite

care a year.

5.67

This increased level of access to respite care is subject to state and

territory governments matching the Australian Government's offer and managing

combined funds to directly assist older parent carers. As part of the

announcement, the Minister for Family and Community Services indicated that

this Budget measure would be implemented via bilateral agreements between

Australian Government and state and territory governments under the

Commonwealth State Territory Disability Agreement.

5.68

A number of submissions argued that while they welcomed the additional

respite care being made available it did little to address the need for

long-term accommodation. Additional respite did not address the concerns of

family carers that their loved one would be well cared for when they were no

longer able to do so themselves.

Recommendation 24

5.69

That Commonwealth, State and Territory governments, as part of their

commitment to life long planning for people with disabilities, ensure:

- that transitional arrangement options are available for people

with disabilities who are cared for by ageing family members; and

- that there are adequate options for people with a disability and

their carers to plan for their futures.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page