Quantifying the impacts of stillbirth

3.1

Stillbirth has far-reaching impacts on individuals, families,

communities and Australian society. However, the economic and social costs of

stillbirth are not widely recognised, and there has been limited attention to

quantifying these costs in the Australian context.

3.2

International researchers found that the direct financial cost of care

associated with a stillbirth was 10−70

per cent greater than the cost of care for a live birth, and that the costs

were predominantly met by government.[1]

3.3

Research conducted in the United States indicated that women whose

babies were stillborn, particularly where the cause was unknown, had

significantly higher hospital costs during labour and birth than women with

live births, while in England and Wales there were increased costs for

subsequent births as a result of more intensive surveillance of the pregnancy.[2]

3.4

More detailed research is required to guide national policymaking,

funding decisions and future corporate investment, as well as to better target

stillbirth research and education programs.[3]

According to the Centre of Research Excellence in Stillbirth (Stillbirth CRE):

The economic impact of stillbirth is significant and far

reaching and extends further than just the direct costs to the healthcare

sector. One important area in which major employer groups might see benefit

from targeted stillbirth research is in the impact of pregnancy loss on women

and their families in terms of time off work, altered work performance, and

other employment-related impacts. Improving bereavement care and recovery after

stillbirth has potential beneficial spin-offs for employers and the broader

economy, and this could encourage investment from the corporate sector.[4]

Direct and indirect costs

3.5

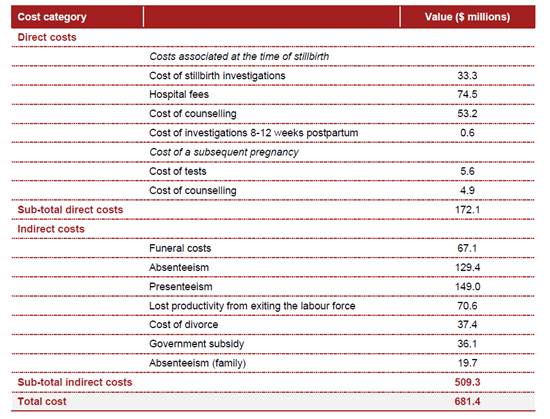

A study prepared by PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PwC) for Stillbirth

Foundation Australia estimated the total projected direct and indirect costs of

stillbirth to the Australian economy to be $681.4 million for the five-year

period from 2016 to 2020.[5]

3.6

The study analysed projected direct and indirect costs of stillbirth in

Australia for the period 2016 to 2020 across 13 categories, as shown in Table 3.1

below.

Table 3.1: Cost of stillbirth in

Australia for the five-year period 2016−20,

in 2016 present value terms[6]

3.7

The PwC study projected that, if the 2016 stillbirth rate of 7.4 per

1000 births remained unchanged, and assuming an increase in the Australian

population and number of births in this five-year period, the number of

stillbirths would increase from approximately 2500 stillbirths in 2016 to 2700

stillbirths in 2020.[7]

3.8

In addition to the above projection, the study calculated the cost of

lost future productivity of the stillborn child in 2016 as $7.5 billion in 2016.

PwC acknowledged that these costs were more difficult to quantify, but noted

that they 'have serious impacts on people and society' and are no less

important than the readily quantifiable costs included in the study.[8]

3.9

Stillbirth CRE noted that preliminary efforts to quantify stillbirth costs

suggest that direct hospitalisation costs associated with the time of birth is

$9630 for women who had a stillbirth and $6690 (30 per cent lower) for women

who did not. This calculation did not take into account the ongoing costs of

support, bereavement care and counselling, or the difficulty in returning to

work.[9]

3.10

Other research projects are underway that focus on identifying and

quantifying the costs of stillbirth to the nation, including a collaborative

research project between the Australian Institute of Tropical Health and

Medicine at James Cook University and the Stillbirth CRE.[10]

3.11

The Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI) also noted that there are

significant costs to the community as a result of poor fetal health, even when

a baby is born alive, and advocated that researchers should not solely focus on

stillbirth, but also consider the ongoing risk of babies being born with

long-lasting effects.

When the baby does not grow well in utero, the ongoing impact

is great—the

likelihood of doing well in school and securing a good job is reduced, the

likelihood of a decreased life expectancy and developing of heart disease,

diabetes and kidney failure is increased, particularly in vulnerable

populations. The resulting impact to Australia’s economic and social wellbeing

is vast.[11]

3.12

One witness advocated that a longitudinal study on the social and

economic impacts of pregnancy loss be undertaken by the National Centre for

Longitudinal Data (NCLD).[12]

3.13

The NCLD, funded by the Australian Department of Health, is a national

population study examining the health of over 57 000 Australian women. The

study includes data on the number who have experienced a miscarriage or

stillbirth. However, it does not gather information about how experiencing

stillbirth affects the woman's future health. Professor Gita Mishra, Director,

Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health, noted that this is an area

that demands further research in order to identify women at risk of future

health conditions.

I think that's so important—apart from her mental health. It

could be an underlying condition that puts her at risk of maybe future

cardiovascular diseases, as we've seen with other conditions. So, I think it's

a big program that we really need to understand. If there are risk prediction

models with accurate prevalence data, we can tell women what they're getting

into and how we can avoid that situation for them. But, also, then what happens

to her health and wellbeing in the future?[13]

Impact on families

3.14

Evidence presented to this inquiry clearly showed the significant

financial impact that a stillbirth has on individual families. Some of the

unexpected costs included:

- costs associated with the autopsy process including transporting

the baby to the autopsy, travel and accommodation for the parents, and the cost

of the autopsy itself;

-

costs associated with a funeral, cemetery site and gravestone;

-

the cost of grief counselling;

-

extended periods of unpaid leave or part-time work;

-

costs associated with an inability to return to work; and

-

the cost of additional medical care associated with subsequent

pregnancies.[14]

Autopsy costs

3.15

The Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia (RCPA) reported that

costs of autopsies vary depending on complexity, and provided an example of one

major public service charging $2500 per autopsy.[15]

3.16

The Victorian Perinatal Autopsy Service reviewed the cost of a perinatal

post-mortem examination in 2016, and found that the cost depended on the

complexity of the examination, as follows:

- full post-mortem examination: $1976−$2673;

-

limited post-mortem examination: $1279−$1859; and

-

external post-mortem examination: $654−$866.[16]

3.17

Dr Diane Payton, Chair, Paediatric Advisory Committee, RCPA, pointed out

that most autopsies are conducted on a voluntary basis due to the lack of

funding.

This leads to virtually all of them being done in public

hospitals, which for me is a good thing. But it also does mean that in a

department, where the director is really looking after his budget and there is

no funding for the perinatal autopsy, it really does get pushed to the bottom

of the pile. Here is a departmental director who's looking at one of his

pathologists maybe spending a whole day, when you add up the performance of the

autopsy and the reporting, for which they could have been reporting 60 small

biopsies, and they would have had money coming in, or medical benefits accrued—the

sort of funding they count on their books—whereas for the autopsy there is

nothing.[17]

Medicare and other healthcare benefits

3.18

Whilst Medicare benefits are available for standard medical care costs,

there are a number of services for which benefits are not available. For

example, pathology services performed on stillborn babies do not quality for payment

under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS).[18]

3.19

Professor Hamish S Scott and Associate Professor Christopher Barnett

noted that current MBS funding for perinatal autopsy only provides for anatomic

analysis, and not genetic analysis. They argued that MBS funding processes need

to become more flexible in order to deal with such rapid advances in medical

research and technology, and estimated that MBS funding of $4000 per autopsy

would provide an answer for up to 50 per cent of cases involving stillbirth or

congenital abnormalities leading to death.[19]

3.20

The Parental Leave Act of 2010 (Cth) provides that a person is

eligible for Paid Parental Leave or Dad and Partner Pay where the child is

stillborn or dies. The welfare payment is linked to an entitlement to unpaid

parental leave.[20]

3.21

Parents of a stillborn child may also be able to access Centrelink

benefits through the Stillborn Baby Payment, although there are time limits on

applying and eligibility criteria in the form of income and/or work tests.[21]

3.22

Insurance policies may also have limitations in relation to health care

claims resulting from stillbirth. One submitter discovered that her insurance

policy excluded certain depressive and anxiety disorders, meaning that she was

ineligible to make a claim as a result of seeking psychological support

following stillbirth.[22]

Families in rural and remote

communities

3.23

As noted in Chapter 2, the closure of small maternity units in rural and

remote communities across Australia has had an impact on maternity health

outcomes for pregnant women living in those communities, including additional financial

impacts as a result of having to travel long distances to receive maternity

care, and a higher risk of stillbirth because women may be less likely to leave

their community to seek antenatal care until late in their pregnancy.[23]

Intangible costs

3.24

The intangible costs of stillbirth are more difficult to quantify, and as

such have tended to receive less attention from policymakers. However, it is

clear from research that they play a major role in families' circumstances and

have a rippling effect across communities.

Stillbirth exacts an enormous psychological and social toll

on mothers, fathers, families and society. It is estimated that 60−70% of affected

women will experience grief-related depressive symptoms at clinically

significant levels one year after their baby's death. These symptoms will

endure for at least four years after the loss in about half of those women.[24]

3.25

Researchers have noted that intangible costs contribute to the

longer-term economic burden of stillbirth as a result of the higher level of

anxiety and depression in families experiencing stillbirth compared to other

families.[25]

3.26

The PwC study analysed five intangible costs associated with stillbirth

in Australia: the impact on mental well-being; relationship with partner;

relationship with others (family and extended family); other children; and the

effect of financial loss. It found that stillbirth had a profound psychological

impact on parents.

Many suffer from grief and anxiety, the effects often lasting

long periods of time. Experiencing a stillbirth caused stress and anxiety in

subsequent pregnancies and some parents received counselling to deal with this

increased level of stress. Stillbirth put considerable strain on marital or

partner relationships. Different grieving patterns between men and women,

blame, anger and resentment were often cited. Some couples separated after the

experience.[26]

3.27

Other flow-on effects for families may include increased fear and

anxiety amongst other children, and social isolation.[27]

These psychological effects may adversely impact on their daily health, functioning,

relationships and employment.[28]

Costs can no doubt be attributed to each of the above issues

by economists, but how do you quantify the impact of a stillborn baby on its

family? Without wanting to be overly dramatic, Joshua’s death traumatised me in

ways I cannot always describe, and impacted on the mothering of my other two

children. I was diagnosed with breast cancer six years after Joshua’s birth,

and although there is no evidence, I strongly believe the grief I experienced

after Joshua, and the stress of my subsequent pregnancies played a role in

this. I was 36 at the time of diagnosis.[29]

3.28

In addition to the emotional grief and trauma of stillbirth, bereaved

families are often faced with longer-term financial burdens that extend well

beyond 12 months after the loss.[30]

...I keep needing to see new specialists for things that we're

still trying to find answers for. Now I'm struggling with infertility, so I'm

going through IVF, which is partially Medicare rebated. Counselling is another

thing that I've utilised. It has been very helpful to have access to the mental

healthcare plan, but I don't think it's enough to subsidise 10 sessions a year

for something that's as profound and ongoing as this.[31]

...

My husband and I were both self-employed. I was an IT

consultant, and my husband has an electrical contracting business. He couldn't

take time off. His staff tried to keep things going, but we had no such thing

as paid leave, and ultimately we moved out of Sydney, partly for economics.

That was an economic outcome of the death. I completely change[d] careers as a

result. We went from a staff of five electricians down to just my husband.[32]

...

It’s fair to say that my productivity was severely impacted

by my loss experience. I struggled to concentrate, and I found it difficult to

re-discover purpose in my work. I found group situations challenging, including

leading meetings and presenting to groups. I had lost all confidence. This was

my experience, despite my having accessed extensive bereavement counselling

through (then) SIDS and Kids—both

individual and support groups, and actively working hard to rediscover hope and

happiness after loss.[33]

...

...I now find myself mentally unprepared to re-join the

workforce in the immediate future due to a lack of drive and mental capacity to

be able to fulfil work obligations. Re-joining the workforce too soon may

result [in] a phenomenon known as presenteeism, where an employee is physically

present, but mentally absent. Further, the prolonged period of remaining at

home without an active income will eventuate in financial burden, and

potentially a strain on the relationships within the household.[34]

Impact on healthcare providers

3.29

The College of Nursing and Health Sciences at Flinders University noted

that some of the direct and indirect costs of stillbirth are borne directly by

healthcare providers. These include increased medical and health care costs,

costs associated with subsequent pregnancies which would be regarded as

high-risk, and costs associated with stillbirth investigations and reporting.[35]

As one bereaved parent explained:

Extended leave from the workforce, and impacted productivity

are not the only impacts with respect to quantifying the impact of stillbirth

on the Australian economy. It is important to also take account of the impact

on the public health system of subsequent pregnancy care...This increased level

of specialist care by an esteemed, senior medical professional, certainly came

at a cost to the public health system. With this replicated more than 2000

times every single year, it is clear to see that we have an unacceptable and

unsustainable situation on our hands.[36]

3.30

The economic impact of stillbirth also extends to clinicians and other

health professionals who care for those experiencing stillbirth, although this

impact is not accounted for when quantifying the costs of stillbirth. As Ms

Victoria Bowring, Chief Executive Officer, Stillbirth Foundation Australia, explained:

Obstetricians, midwives and the nursing staff all feel this

loss at the same time, and that wasn't taken into account. I'm sure there would

be many workers who find it difficult to return to their jobs, having sat

beside a family who've gone through this and held their hand and then had to go

home and deal with that themselves. So, whilst we have this figure, it is much

broader than it seems.[37]

3.31

The 2018 Victorian parliamentary inquiry into perinatal services also

heard evidence that short staffing combined with overtime and double shifts had

led to workplace stresses for midwives, leading to increased sick leave,

reduction in working hours, or even leaving the workforce.[38]

3.32

Professor Craig Pennell, Senior Researcher, HMRI noted that, whilst

considerable effort goes into training so that staff can deal with the

emotional stress surrounding stillbirth, it takes a particular type of person

to do so repeatedly. He noted that:

...there are staff who are involved, especially in the unexpected

cases or cases that happen in labour, who would not attend work for a week or

weeks. I know of staff who have left the profession because of stillbirths that

were particularly unexpected, or where the management of those cases wasn't

good, or where there was blame or the junior staff were blamed. But every case

is, obviously, different.[39]

3.33

The loss of skilled staff as a result of these pressures is therefore a

significant issue that needs to be factored into the calculation of the economic

impacts of stillbirth on hospitals and the healthcare system.

Employment-related costs

3.34

Stillbirth has a significant economic impact on employees, employers,

and the labour force more generally. Bereaved parents may withdraw from normal

social activities, including labour force participation, in the aftermath of

stillbirth, with life-long implications for the economic status of women and

their families.[40]

3.35

Stillbirth CRE estimated that the annual cost of one mother missing from

the labour force as a result of stillbirth was $33 000 in Gross Domestic

Product.[41]

3.36

PwC concluded that, even in cases where a bereaved mother has to return

to work for financial reasons following a stillbirth, her productivity is

estimated to be 26 per cent of her normal rate after 30 days.[42]

Leave following stillbirth

3.37

A key issue raised by witness and submitters in relation to employment

matters concerned leave entitlements for parents who experienced a stillbirth.

3.38

According to the International Labour Organisation, compulsory leave of

six weeks should be provided to all women in the event of a stillborn child, as

a health-related measure. However, only 12 of 170 countries with maternity

benefit policies include any specific provision for stillbirth-related leave,

while others have leave provisions that protect parents from discrimination

based on maternity.[43]

National Employment Standards

3.39

In Australia, the National Employment Standards (NES) of the Fair

Work Act 2009 (Cth) provide for minimum leave entitlements for all employees

in the national workplace relations system. Other leave entitlements available

under an award, registered agreement or contract of employment cannot be less than

those contained in the NES.[44]

3.40

Parental leave under the NES of the Fair Work Act is unpaid leave,

although many employees are entitled to various degrees of paid parental leave

under various industrial instruments, including enterprise agreements and some

awards. These employees keep this paid entitlement as it is a benefit in excess

of the NES entitlement.[45]

3.41

The Fair Work Act provides for two days' compassionate or bereavement

leave 'each time an immediate family or household member dies'.[46]

3.42

The Fair Work Act provides for special maternity leave for a

pregnant employee who is eligible for unpaid parental leave, where 'the

pregnancy within 28 weeks of the expected date of birth of the child otherwise

than by the birth of a living child'. If an employee takes leave because of a

stillbirth, the leave can continue until she is fit for work.[47]

3.43

An eligible pregnant employee can reduce or cancel their period of

unpaid birth-related parental leave if their pregnancy ends due to their child

being stillborn, or if their child dies after birth.[48]

3.44

State and territory parental leave provisions apply only to those

employees not covered by the parental leave component of the NES (that is,

employees who are award/agreement free). The majority of state and territory

laws are generally consistent with the provisions provided for in the Fair Work

Act. Only New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and

Tasmania have applicable laws, while the ACT, Northern Territory and Victoria

are essentially governed by the Fair Work Act alone (with some exceptions

regarding public service).[49]

Parental Leave Pay

3.45

The Australian government's Paid Parental Leave Scheme, introduced on 1 January

2011, provides access to 18 weeks of parental leave pay for eligible working

parents when they take time off from work to care for a newborn or recently

adopted child. It is fully government-funded. Parental leave pay is not a leave

entitlement, but a payment made to an eligible employee while that employee is

on leave.

3.46

Parents of a stillborn child are eligible for parental leave pay,

although the same income caps and activity tests apply as for paid parental leave

which effectively excludes many employees.[50]

Inconsistent leave provisions

3.47

The Community and Public Sector Union New South Wales (CPSU NSW) noted

that the Fair Work Act appears to contradict the federal allowance provided

under the Paid Parental Leave Scheme. Section 77A, for example, states that

'Pregnancy ends (other than by birth of a living child)', which appears to

allow the employer to cancel unpaid leave in the instance of a stillbirth and

require the worker to return to work. In other words the entitlement is

removed.[51]

3.48

Mr Troy Wright, Branch Assistant Secretary, CPSU NSW, pointed out that

the relevant provisions of the Fair Work Act (sections 77A and 80) are

inadequate because they discriminate between mothers whose children are born

full-term and mothers whose children are not.

Mothers who give birth to a child are recipients of the

government's Paid Parental Leave scheme, whereas mothers experiencing a

stillbirth or miscarriage are reliant upon unpaid parental leave [and] requires

a series of medical certificates in the event of a miscarriage or stillbirth...somehow

the issue of stillbirth and miscarriage is still treated as a medical issue

industrially and is still reliant on medical certificates.[52]

3.49

The CPSU NSW recommended that section 80 of the Fair Work Act be amended:

...to reduce the threshold from 12 weeks pregnancy and also to

ensure that workers are paid special maternity leave at a rate equal to their

pre miscarriage level regardless of the employment status of the worker.[53]

Inadequate leave provisions

3.50

Even where bereavement or other types of paid leave were available to

them, some bereaved parents found that the period of leave was not sufficient

and were forced to take additional unpaid leave.[54]

Tim and Leanne Smith explained that it took time to deal with the grief and

trauma of a stillbirth:

I was not a functioning member of society or the workforce

for at least 6 months. I believe that people need to be given sufficient time

away from the workforce in the first instance to deal with the emotional and

physical turmoil.[55]

3.51

Mrs Jackie Barreau agreed, arguing that the two days'

compassionate/bereavement leave provided under the Fair Work Act is not enough

to manage the emotional, physical and mental impact of losing a child and planning

for a funeral. She recommended that this leave should be extended to five days,

and that flexible workplace arrangements in both public and private sectors

should extend to stillbirth to allow for the bereavement of a family member.[56]

3.52

Mrs Clare Rannard testified that, whilst she was able to access a

combination of workplace maternity leave, paid parental leave and unpaid leave,

she found it difficult to work in a full-time capacity following her daughter's

stillbirth, with implications for her employment security.[57]

3.53

Ms Lisa Martin found that she was ineligible for parental leave because

of strict provisions regarding the classification of 'stillborn'.

My son Carter Jake Martin was born at 19 weeks 6 days and 2 &

half hours just making him a few hours shy of a classified stillborn, therefore

not entitled to recognition of a birth or parental leave. Not only did I endure

the birth I faced the cold hard reality of what was to come after that which

was the effect on our family, my sons and friends, the impact on my job and the

financial position we were in which may see us lose our home.[58]

Employer discretion

3.54

The committee heard evidence about the difficulties and inconsistencies

experienced by employees when seeking access to leave following a stillbirth,

highlighting that employers may lack awareness of the trauma associated with

stillbirth and exercise considerable discretion and control over access to

parental leave entitlements.[59]

3.55

Nick and Elena Xerakias noted that, while Ms Xerakias was not able to

work full-time and could not commit to a full-time position, Mr Xerakias's

employer and colleagues were supportive and, upon his return to work, he was

provided with flexibility in his work hours.[60]

3.56

Ms Naomi Herron was advised by her employer that she had been made

redundant whilst on leave and that she would not receive a payout. She stated

that she worked in a male-dominated industry and her employers seemed to be

unaware of their responsibility to their employees.[61]

3.57

Sands Australia noted that '[s]tillbirth does not satisfy

Centrelink/government maternity leave requirements and this is often the case

for employer maternity leave entitlements'.[62]

Access to maternity leave may be granted at the discretion of the employer. One

submitter stated that her employer had honoured their maternity leave policy

'even though I had no baby', and this had enabled her to work through her grief

and not worry about losing her home.[63]

3.58

Australian Public Service (APS) employees may be able to access accrued

personal leave and paid maternity leave, but parental leave policies in the

private sector are inconsistent and ambiguous.[64]

3.59

Mr Andrew McBride stated that he and his wife were both in the APS at

the time of their stillbirth, and were able to access paid personal and

maternity leave. However, he recalls meeting a newly-grieving mother who had to

return to work because she had no leave and could not afford to take time off

and, when he was later employed in the private sector, he observed that

corporate parental leave policies were often ambiguous as to whether parents of

stillborn babies were entitled to paid parental leave, because they tended to

mirror the provisions contained in the Fair Work Act.

3.60

Since then, he has been working with corporate leaders to ensure recognition

of stillbirth in paid parental leave policies becomes the norm, and that

parents of stillborn children are afforded the same rights as other parents.

Our ask of companies has been straightforward: a commitment

to review company parental leave policies to ensure that employer funded paid

parental leave is available in the circumstance of stillbirth.[65]

3.61

Mr McBride recommended that the provisions for paid parental leave needed

to be clarified in order to encourage private employers to ensure that

employees who experience stillbirth have access to such leave.[66]

I do not believe that the ambiguity in existing company

parental leave policies was through ill-intent but simply neglect—companies have tended to

take the mandated legislative provisions in the Fair Work Act of 2009 (that

focus on unpaid parental leave) and overlay their own paid parental leave

policies, which tend to be cast around the care-giving aspect of parental leave

and just don't consider the circumstance of stillbirth. Consequently, clauses

from the Fair Work Act, such as Section 80 on “Unpaid special maternity”, are

confusingly included in policies that are addressing paid parental leave.[67]

3.62

Annette Kacela and Christopher Lobo reported that, whilst they had

access to some paid leave, their respective experiences of returning to work

were starkly contrasting.

Following the stillbirth of our son Thomas, neither

Christopher nor I were capable of immediately returning to work due to the

sheer devastation, grief and crippling mental effects. We have since returned

to our respective employers to different departments. Christopher’s employer

granted him paid leave for 2 months who was exceptionally supportive of the

circumstances and even contacted him on multiple occasions to ensure his and

our family’s wellbeing. My employer dealt with Thomas’s passing in stark

contrast, I was on leave for four months where I was required to use all of my

personal and annual leave entitlements which I had been accumulating in

preparation for Thomas live birth, the remainder of the time was un-paid...The

non-supportive work culture demonstrated by my employer compounded the

situation we were already in. I was also requested to complete my ‘on-call’

shifts over the Christmas period that I had to decline, this gesture clearly

demonstrated the lack of awareness stillbirth has across various domains including

the healthcare industry.[68]

Best practice employment models

3.63

The Centre for Midwifery, Child and Family Health advocated a review of

employment laws across Australian jurisdictions, using a 'stillbirth lens' to

ensure that bereaved parents are protected and supported in legislation.[69]

3.64

Stillbirth CRE recommended the following benefits to reduce the

financial burden on parents of stillbirth:

- minimum paid period of time off work;

-

respite child care if there are other children or care

responsibilities;

-

Medicare reimbursement for psychiatric or psychological referral;

and

-

equity of parental leave support post stillbirth for both mothers

and fathers.[70]

3.65

One submitter noted that 'parents of babies who die are subjected to a

lot of misinformation on their rights and responsibilities in the workplace',

and recommended that the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman develop a best

practice guide for employees and employers, and a national stillbirth in the

workplace campaign to assist employers and employees to navigate the return to

work after a stillbirth.[71]

3.66

In 2017 Stillbirth Foundation Australia called on private employers to

review their parental policies to ensure that their company extended paid

parental leave in the case of stillbirth. The Foundation listed the economic

and social benefits including removing financial pressure from the bereaved

family, recognising the birth of a child and allowing time for bereaved mothers

to recover from the birth.[72]

3.67

The committee identified two examples of best practice currently

operating in Australia that contain specific provisions for employees who have

experienced stillbirth.

Australian Public Service

3.68

The Maternity Leave (Commonwealth Employees) Act 1973 (Cth) covers

APS employees and ensures that mothers of stillborn children are entitled to

the same maternity leave as mothers of children born live.

3.69

The Act provides for a maximum period of absence of 52 weeks. Under the

Act, a person is required to commence maternity leave six weeks before the

expected birth of the child. Where the child is born earlier than six weeks

before the expected date of birth, the required absence commences on the date

of birth and continues for six weeks. In this case, the 52 week period of

maternity leave absence commences from the date of birth.

3.70

Eligible employees may access the Paid Parental Leave Scheme (PPL

Scheme) or Dad and Partner Pay (DAPP) in addition to entitlements to paid and

unpaid leave provided under individual agency Enterprise Agreements.

Ausgrid Enterprise Agreement

3.71

Maurice Blackburn Lawyers and the CPSU NSW advocated that the provisions

for stillbirth and miscarriage in the Ausgrid Enterprise Agreement, as negotiated

with the Electrical Trades Union, represented best practice and should be

included in the NES. Section 30.8 of the Ausgrid Enterprise Agreement reads as

follows:

30.8 Cessation of pregnancy - stillbirth and miscarriage

30.8.1 Where the pregnancy ceases by way of miscarriage

between 12 and 20 weeks gestation then subject to providing a medical

certificate:

(a) the birth parent will be entitled to six weeks paid

special parental leave; and

(b) the non-birth parent will be entitled to compassionate leave

in accordance with Clause 29 of this Agreement.

30.8.2 Where the pregnancy ceases by way of stillbirth after

20 weeks gestation to birth then subject to providing medical certificate:

(a) the birth parent will be eligible for 16 weeks paid

special leave; and

(b) the non-birth parent will be eligible for one week of

paid special leave.

30.8.3 The leave set out above in this Clause 30.8 may be

added to with approved accrued leave including annual leave, personal carer’s

leave and accrued personal leave.[73]

Committee view

3.72

Stillbirth has significant and far reaching economic effects for

Australia that extend well beyond the direct costs to the healthcare sector.

The committee acknowledges that further research and education is required to

understand the full extent of these impacts and to inform public policymaking

and awareness-raising, including:

- the impact on bereaved parents and their families, including

additional financial pressures associated with additional health care, funeral

costs and, for many, extended periods of unpaid leave, part-time employment or

unemployment;

-

the impact on employers and employees in relation to time off work,

the process of returning to work, and altered work performance;

-

the impact on society when skilled clinicians and health

professionals leave the workforce as a result of the pressures of dealing with

stillbirth;

-

the potential benefits for employers and the Australian economy

of improving bereavement care and recovery after stillbirth; and

-

the potential for greater investment in innovative research and

education from the corporate sector if the economic benefits of improved

bereavement care and recovery are more widely recognised.

3.73

The committee recognises that providing protection and support for

employees who have experienced stillbirth is a priority across Australia's

jurisdictions. It urges the federal, state and territory governments to review

employment laws and policies with a 'stillbirth lens' and make necessary

changes to ensure that appropriate protection and support provisions are in

place.

3.74

The committee acknowledges the success of the Stillbirth Foundation

Australia campaign in urging private employers to formally recognise stillbirth

in their corporate policies by ensuring that their company extends paid

parental leave to employees who have experienced stillbirth. The committee

agrees with the approach proposed by Mr McBride and the CPSU NSW, that the

relevant provisions of the Fair Work Act should be clarified and strengthened

to encourage private employers to review their workplace policies and afford

employees who experience stillbirth the same access to paid parental leave as

other parents.

Recommendation 1

3.75

The committee recommends that the Australian government reviews and amends

the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) and provisions relating to stillbirth in

the National Employment Standards (NES) to ensure that:

- provisions for stillbirth and miscarriage are clear and

consistent across all employers, and meet international best practice such as those

contained in the Ausgrid Enterprise Agreement; and

-

legislative entitlements to paid parental leave are unambiguous

in recognising and providing support for employees who have experienced

stillbirth.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page