Clinical trials for people with low survival rate cancers

3.1

This chapter examines two distinct issues with respect to clinical

trials for people with low survival rate (LSR) cancers: barriers to accessing

trials and jurisdictional issues for trials.

3.2

The Garvan Institute of Medical Research/The Kinghorn Cancer Centre/The

Garvan Research Foundation (Garvan Institute) outlined in its submission the existing

ways in which patients without any standard treatment options can access

clinical trials, and noted that '[t]he first step in improving the outcomes for

rare and high-mortality cancers is to engage patients in the research

enterprise. Without data, nothing can improve'.[1]

The treatment access options are as follows:

-

phase 1 clinical trials – as these

are primarily focused on defining the toxicity profile of a new treatment, it

takes a long time to get sufficient numbers of participants and they are costly

and intensive, limiting the number of phase 1 studies that a single institution

can open at one time.

-

phase 2 or 3 clinical trials,

however, cost limits the number of phase 2 studies that can be run

simultaneously at any one institution.

-

compassionate access to new drugs

and off‐label treatment. This is common practice in Australia,

and while it may produce anecdotal insight into novel therapeutic

possibilities, these results are idiosyncratic, ad hoc, unsupervised and

unregulated, and mostly go unreported, thus failing to contribute to the body

of knowledge. Most importantly, ineffective treatment is likely to be

underreported.[2]

3.3

The Garvan Institute further noted that the 'two key barriers to

improved outcomes for less common cancers' are lack of access to clinical

trials, and lack of access to the best available treatments, which are

'[i]nextricably linked', because:

As governments use information gained from trials when

deciding if they will fund a new drug, it is critical that patients with less

common cancers have access to clinical trials, and that government, academics,

clinicians and the pharmaceutical industry work together to develop trials for

these cancers, as well as the more common cancers. Currently, there is a real

disconnect between the identification of a new treatment by researchers and,

where relevant, access to these treatment options.[3]

3.4

The relationship between clinical trials and the Therapeutic Goods

Administration (TGA), the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) and

the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), as well as philanthropic and

pharmaceutical funding for clinical trials, were examined more generally in

chapter 2.

Barriers to accessing trials

3.5

There are a number of barriers to accessing trials, including the

absence of trials for LSR cancers, identifying the availability of trials, meeting

the trial criteria and having the physical and financial means to participate

in a domestic or international trial.

3.6

The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (Walter and

Eliza Hall Institute) identified the following 'recurring themes' with respect

to the challenges to establishing clinical trials in Australia:

- access is limited for patients with rare cancers, as

trials will not be available in all major treatment centres;

- access for patients in rural Australia is difficult when

the trial requires frequent attendance at a capital city centre;

- the time taken to establish a trial is

disproportionately long compared to the survival time of patients with low

survival cancer; and

- pharmaceutical companies are risk adverse when it comes

to initiating adequately sized trials in cancers with low incidence.[4]

3.7

Mr Tim Eliot identified several barriers to his participation in

clinical trials which caused him to accept standard of care treatments[5]

for his glioblastoma:

...admin did not provide details of the trial; existing

treatment timing meant the trial start date was missed by a week; my tumour was

in the wrong location; the trial was already full; the trials were not being

run in Western Australia; etc, etc.[6]

3.8

Mr Eliot opined that:

...these symptoms show the

current funding model is based on standard clinical research practices with a

limited number of patients able to be involved, and little, if any, data

sharing between trials.[7]

3.9

Mr Eliot argued that '[t]his approach is simply not working'[8]

and although he acknowledged that '[t]here are valid reasons for clinical

standards to be set high, particularly in researching new treatments',[9]

he submitted that 'standard, slow, phased clinical trials are not the only way

forward' and discussed the GBM AGILE model as an alternative.[10]

The Cure Brain Cancer Foundation (CBCF) noted that this particular trial had an

'innovative trial design' and 'an adaptive trial platform, which has great

potential to reduce timeline[s] through seamless transition from Phase 2 to

Phase 3 within the trial'.[11]

Access to this trial is further discussed in chapter 5.

3.10

The following sections examine some barriers to accessing trials that were

repeatedly cited during the course of the committee's inquiry.

"Dr Google"

3.11

In addition to people independently searching the internet for

information about inexplicable symptoms[12]

or about a disease following diagnosis,[13]

the committee heard that people resort to "Dr Google" to find

out information about access to trials. For example, Ms Marilyn Nelson, who has

lung cancer, described how she conducted her own research on clinical trials in

order to find 'some hope':

We are looking for news about trials and new drugs that are

coming along. There is not that much information about it here in Australia, so

we look to Google and we look to proper websites over there to try to find—just

some hope, you know? That is what we are looking for, that there might be

something.[14]

3.12

Professor Mark Hertzberg of the Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma

Group (ALLG) considered that it is now easier, with the internet, to access

information about clinical trials, noting that patients:

...come with wads of paper, particularly the relatives of the

patient and the children of the patient. The clinicians also have better access

[to information about trials] than ever before.[15]

3.13

Indeed, Professor David Walker opined that the approach of searching the

internet for treatments occurs '[a]ll the time', as:

...a patient with a brain cancer will be told they need an

operation, they will be told the diagnosis and 'This is what is going to happen

to you'. There is very little information given to them up-front and there is

certainly no information in almost all circumstances about available trials and

what that might have to offer.[16]

3.14

Ms Julie Marker of Cancer Voices Australia also suggested that

clinicians may be unfamiliar with LSR cancers and associated trials, which in

turn can raise a whole host of problems:

Often clinicians are not so familiar with these rare cancer

types and the trials. So there may well be opportunities for treatments that

people are just not aware of both from the clinicians and from the consumers

side of it to find the best treatments, or even the clinicians who are in any

way familiar with treating these conditions. Often that means travelling to

other locations. Again, you have to be wealthy enough to afford to do that

because that is not supported. There is the potential for duplication if there

is not some register of even the preliminary pilot studies.[17]

3.15

This issue about the lack of information available to patients was also

reflected in the evidence from Mr Evan Shonk and Mrs Suzanne Turpie:

CHAIR: One of the other things that a number of you

have mentioned was clinical trials. I am interested in what sort of information

you were given about clinical trials and how much you had to go away and

research for yourselves.

Mr Shonk: There is virtually none available. They

pretty much do not exist.

CHAIR: Someone mentioned to me that there are not even

any brochures available about brain cancer.

Mrs Turpie: Yes. We did not encounter any brochures.

We were just sat in a room and told, 'This is a clinical trial that kids with

medulloblastoma are on.' To be honest, there was nothing given to us, it was

scary and I felt like my son was being used for research himself while he was

still living.[18]

3.16

Similarly, in her evidence to the committee, Ms Jill Emberson, who has

ovarian cancer, expressed her surprise that 'there is not more clear

information available about running trials', but also identified why this may

be the case:

...I understand that all the people running the trials are so

strapped in even getting their trials up and running and that the

administrative support, as I understand, is also a real barrier to people

running the trials inside the hospitals and the labs. And that that would be stopping

trials getting up and running, I find, gobsmacking.[19]

3.17

Mr William Williams, whose wife passed away from a GBM grade 4, also spoke

of his experience of finding out information about trials:

There is a website that I did look at, which did not really

lead me anywhere in particular to the possibility of a trial. So it was in fact

drawing on the experience of Denis and other people I knew in the brain tumour

area, and just saying, 'Who do you think might be running a trial?' Denis said,

'Well, you can call so and so in Melbourne', and I did. After announcements of

other initiatives in cancer research in this country, I called and just said

who I was. But there was no coordination or leading me in any way that showed

me a direction where there could be a trial. So you just cold-call and say who

you are and say, 'Can you help?' because it was not available.[20]

3.18

As Mr Todd Harper of the Cancer Council Victoria (CCV) observed, the

motivation of cancer patients to seek out the clinical trials available to them

'speaks to the value of having information that is consumer friendly and is

able to guide them towards these types of activities'.[21]

AustralianClinicalTrials.gov.au

3.19

The committee was informed that information about trials is available on

the AustralianClinicalTrials.gov.au website, developed by Cancer Australia in

partnership with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, the

University of Sydney and Cancer Voices.[22]

3.20

Dr Alison Butt of Cancer Australia provided the following

information about the website:

...the Cancer Australia website supports the only national

cancer clinical trials website which gives consumers access to current clinical

trials in Australia and to Australian arms of international trials. A

particular focus of the website is that it's consumer friendly. So there are

consumer lay descriptions of the trials, which obviously help when patients are

looking for appropriate trials. There are simple search functions which enable

them to navigate through the site and find trials that are eligible. In

addition, there's also specific information about the eligibility of the trials

and the implications of the trial participation. So the focus of the website is

really aimed at trying to encourage participation by making it a very

user-friendly experience.

As you alluded to, the data for the Australian cancer

clinical trials website is sourced from the Australian New Zealand Clinical

Trials Registry, the ANZCTR, but also ClinicalTrials.gov, which is the US

clinical trials website. It is dependent on the clinical trials being

registered, and the responsibility rests with the investigator and sponsor of

the clinical trials, so that is potentially a challenge. It is their

responsibility to update and provide information on that website.[23]

3.21

Although this description indicates that the website contains a wealth

of information about clinical trials, the committee heard that people living

with cancer are not accessing this information due to the difficulty they

experience navigating the website.[24]

3.22

Mr Greg Mullins of Research Australia proffered why this may be the

case:

I think it is extremely difficult for individual patients to

know what clinical trials might be suited to them. In nearly all cases they are

going to be relying on their treating doctor to be able to assist them to

understand whether they are eligible or not. There are searches that can be

done and, if someone perhaps gets really lucky and really knows what they are

doing, they might be able to find that information, but most people are going

to be relying on their doctors to assist them with that.

We have undertaken public polling in the past, where we have

asked people about clinical trials: are they aware of them and what they are?

Typically, what they are telling us is: 'I rely on my doctor.' That is very

much where it is at. I know the last speakers were talking about the difficulty

of understanding even the range of clinical trials happening within Victoria.

On a global scale, that is enormous, and it is not the patients who are in a

position to do that. It really is a matter of ensuring that our researchers and

our organisations are connected globally and understand what is happening.[25]

3.23

Indeed, Professor R John Simes considered that doctors are the 'main

people' who view the AustralianClinicalTrials.gov.au website, but noted that the

website, which contains 'a lay description so that the information is in less

threatening terms', is also accessible to members of the community.[26]

Despite this, Professor Simes considered that improvements could be made to the

website, as:

...to work out whether a particular trial is suitable for a

particular patient still requires a discussion with their doctor et

cetera...while one thing is to be able to find out what trials are available, the

other thing is—if the trial is not available at your site, in your city or at

your hospital—how can you get access to other places. They are really important

issues.[27]

3.24

This was reflected in Mrs Madeline Bishop's submission, where she

asserted that, when looking at the website:

...one needs to know exactly what one is looking for to be able

to locate and be included in a trial. When looking for non-government or

partially funded trials, one must seek information from the individual groups

and their current trials. This haphazard method is not good enough for the

individual whose health and wellbeing is already compromised by their cancer.[28]

3.25

Indeed, Ms Susan Pitt also informed the committee that some trials, such

as physician-led trials, may not be listed on the website.[29]

3.26

In its submission, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)

referred to survey results which 'demonstrate that the lack of awareness of

relevant trials is a barrier, not just to increased participation, but also to

increased cross-referral of patients by general practitioners or clinicians'.[30]

3.27

In response to this, the NHMRC has been 'working to improve recruitment

into and awareness of clinical trials' in the following ways:

- enhancing the functionality of the

AustralianClinicalTrials.gov.au website to bring together resources for

consumers, participants, researchers and proponents of clinical trials, and as

a tool to encourage patient recruitment, and

- developing a national marketing campaign to improve

awareness of the website and an understanding of the role and value of clinical

trials. Funding for the campaign has been provided by the Department of

Industry, Innovation and Science.

3.28

The NHMRC noted that '[i]mprovements in cross-referral rates of GPs and

clinicians have also been observed through the use of a Mobile Applications

(‘Apps’) - ClinTrials refer'.[31]

3.29

However, in response to a question about the accessibility of the

website, Adjunct Associate Professor Christine Giles of Cancer Australia conceded:

We can certainly look at different ways of directing people

to the website—through social media and some of our existing mechanisms. The

consumer organisations, we would anticipate, would do that as well. But, given

the comments that you're making, we would certainly be able to have a look at

that.[32]

3.30

Mr Harper spoke to the committee about the CCV's clinical trials website,

Victorian Cancer Trials Link (VCTL), informing the committee that, following a

redevelopment, the CCV had successfully made the website 'more user-friendly

and searchable for individuals' and as a result, 'there has been quite a lot of

interest right across Australia' and internationally.[33]

Mr Harper elaborated on the redevelopment process:

The recent website redevelopment was done with patients. We

wanted to make sure that the final product was one that was very user friendly.

Since the redevelopment of the website we saw in May this year the website

attracted 3,130 visits from users, which was a 30 per cent increase from prior

to the introduction of the new website. At least on those initial numbers we

are very confident that it has responded to the need of cancer patients.[34]

3.31

Mr Harper suggested that the CCV clinical trials could be 'made

available more broadly', noting that:

I am sure that my Cancer Council colleagues, for whom

clinical trials is a priority, would be very happy to work on expanding what

was essentially a prototype developed in Victoria and making that available

nationally. Obviously, having a site that is already established and has

demonstrated feasibility may offer some advantages.[35]

3.32

However, Mr Harper identified that some issues would need to be

addressed, including:

...encouraging clinical trial sites to contribute data. That is

done under a funding model in Victoria, as I said. Currently it is about

$200,000 in Victoria. Ideally, we would like to increase that in Victoria to

make that available or provide a greater incentive for organisations to submit

their trial's information. I do not see any reason why that could not be looked

at as a prototype that could be rolled out across Australia. My guess is that,

if that was done, funding would be between $1 million and $2 million, probably

closer to two, to enable incentives for trial sites to submit their data and

also to upkeep the website and promote that website.[36]

3.33

Mr Harper outlined the benefits of this approach:

The two principal benefits of that that, I see, are: firstly,

to provide access in a form that has been demonstrated to work well with

consumers; and secondly, to enable trial sites to use that to recruit patients

to their clinical trials. I think that that would be quite a substantial

benefit as well. I should also note that the Ian Potter Foundation was very

generous in providing us funding to enable the website to be recently

redeveloped.[37]

Eligibility for trials

3.34

Many people who have LSR cancers may be ineligible for trials because of

their current state of health, prior treatment, or their age.

3.35

For example, Ms Linda Ferguson, who lost her wife to brain cancer,

informed the committee that:

We asked our various specialists in Canberra and in Gosford

if there were any trials that were suitable. We were told that there were not.

We did research online to see if we could come up with anything, but we found

that, once you make particular treatment choices, you are given a particular

drug or the tumour recurs, suddenly anything that might have been eligible you

are no longer eligible for, because you have already had another drug. So the

doors close very quickly once you have made treatment options. With time being

such a pressure, you make those treatment decisions as quickly as you can.[38]

3.36

Mrs Raechel Burgett, who has a grade-3 oligoastrocytoma, stated that to

access certain trials, she would need to be on her 'deathbed':

I looked and I applied but it is all for grade 4 astrocytomas

because that is the worst and the deadliest. They are opening all the trials

for them, and even at that stage it is not until you are terminal that they

really let you in. I am someone who is still relatively early in their

diagnosis and who has a few years up their sleeve, and so they will not me let

in until I am on my deathbed.[39]

3.37

Mrs Tracy Taylor also described how her son, who has brain cancer, could

not access trials for various reasons, including his prior treatment and age:

My son has already had the gold standard of treatment and

radiation a couple of times, so that in itself makes him not applicable for

trials. His age as well makes him not eligible for trials. If they know from

the start and they have other treatments, as they are calling them, or ones

that are yet to be made and they are yet to trial that they can maybe go on

this path of this new thing, as opposed to just doing the gold standard of

treatment, which then makes them not eligible to do other trials.[40]

3.38

The timeframe within which a person can be eligible to begin a trial can

also be quite tenuous. For example, Ms Simone Leyden of the Unicorn Foundation recounted

a story of a patient who managed to join to a trial after her oncologist initially

informed this patient that no trials were available. Ms Leyden noted that '[i]f

she had literally waited another 24 hours, she would not have been eligible for

that trial'.[41]

3.39

In addition to the eligibility criteria, Ms Nelson informed the

committee that '[t]here is a strict protocol' when you are in a trial,

explaining that:

I cannot have had this and I cannot have had that to get into

the trial. Then, while I am on the trial, I cannot use any other therapy. If I

do, my doctor would have to agree to it. The only reason they would stop the

trial would be if the trial ends or I get progression, which is going to be

picked up on one of the regular scans and then I am bumped out of the trial and

we find out which drug I was actually on. That then decides what is

next—whether it is chemo next or whether there is actually another targeted

therapy that I can try. Yes, there are very strict guidelines for getting in

and there are certainly very strict guidelines—you cannot undertake any other

treatments while you are on the trial. But it is better than the alternative.[42]

3.40

In its submission, the NHMRC noted that the criteria for eligibility 'are

usually determined by the clinical trial sponsor', such as a pharmaceutical

company or a clinical trial network.[43]

It was noted that:

Paradoxically, a sponsor’s legitimate aim to reduce

confounding factors and thus ensure that a clinical trial produces the highest

quality evidence of efficacy, may result in narrow eligibility criteria that

significantly lower recruitment.[44]

3.41

Dr Melissa Grady of AstraZeneca explained why inclusion/exclusion

criteria are in place:

It is not an exclusion by want of exclusion. It is simply

that, if you follow the science and you want to make sure you have answered

that scientific question of that drug or innovative therapy, you must be quite

rigorous around the protocol that you design. By virtue of that, it means you

have a certain population to study and study very well so that you get the

right answer at the right time and that you are not wasting time as well.[45]

3.42

On the other hand, the eligibility criterion used by Professor David Thomas

of the Garvan Institute for his work in advanced genomics and personalised

therapy for people living with incurable rare cancer, is that his patients are

unable to access other trials:

...we have actually designed our modules with exclusion

criteria that say: 'The diseases where there are existing trials which people

can get access to are excluded from this because there are other trials

available. It is the people who do not have the trials available that we are

selectively screening.' And we have 170 of those within nine months; we have

600 by the end of this year. There is a huge population that just cannot get

access to trials.[46]

Australians in regional and remote

areas

3.43

People with cancer in rural and regional Australia also face additional

barriers in accessing clinical trials. This was illustrated in the submission

received from Mr Denis Strangman AM, whose wife passed away 11 months

after her diagnosis with a glioblastoma multiforme grade iv brain tumour:

...as a general rule, patients from regional centres do miss

out, unless they can travel to a major centre. From my knowledge the Canberra

Cancer Centre, as an example of a regional centre, has not so far participated

in an adult brain tumour clinical trial locally, although some of its patients

have – by travelling interstate.[47]

3.44

Ovarian Cancer Australia observed that:

Patients from rural and regional areas opt out of trials

because of the long distances travelled, the cost of travel and finding

accommodation and the rigours of travelling while feeling unwell from their

illness or the treatment they are undergoing.[48]

3.45

The committee also heard from numerous witnesses about the variations in

survival for people living with cancer in regional and remote areas versus

those in metropolitan areas.[49]

3.46

For example, CCV noted that '65% of people with cancer living regionally

survived five years after diagnosis, compared to 69% of people living in a

metropolitan Melbourne region', and provided the following table which

illustrates the five year survival rate for metropolitan and regional

integrated cancer service regions in Victoria, with the regional integrated

cancer services highlighted.

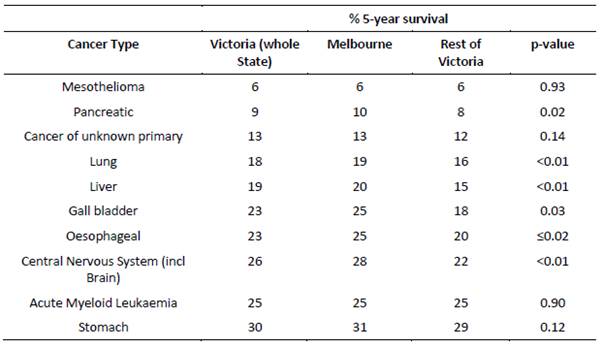

Table 5: Five-year

survival rates for Victorian Integrated Cancer Services[50]

3.47

CCV also provided information about the differences in five-year

survival for low survival cancers between metropolitan Melbourne and the rest

of Victoria, which illustrates that, in many instances, people with LSR cancers

living in regional areas have poorer survival outcomes compared with those in

metropolitan areas.[51]

Table 6 presents this data over a five-year period.

Table 6: Five-year

survival for low survival cancers between metropolitan Melbourne and rest of

Victoria[52]

Funding for travel

3.48

In discussing the barriers to clinical trial participation, the

Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre (VCCC) submitted that, although the

'largest regional centres can conduct clinical trials, as they have the economy

of scale required':

...a recurring theme in recruiting for clinical trials is that

patients from rural and regional areas opt out of trials because of the long

distances travelled, the cost of travel and finding accommodation and the

rigours of travelling while feeling unwell from their illness or the treatment

they are undergoing.[53]

3.49

In his evidence to the committee, Associate Professor Gavin Wright of

the VCCC identified the 'regional-rural problem' as the 'No. 1' struggle in

recruiting people for clinical trials:

The kind of surgeon I am is not a common surgeon, so the

practice tends to come to me. I look after people from Launceston,

Albury-Wodonga, even Adelaide, Mount Gambier and all of Victoria. If I have a

trial on at my institution someone from Mildura or somewhere does not get any

reimbursement to turn up for a trial presentation. They can only get what

limited funding there is from state governments for assistance for actual

clinical presentations only, not for turning up to a trial test.[54]

3.50

Indeed, in advocating for centres of excellence for people with neuroendocrine

tumours (NET), Ms Leyden observed that:

The problem, obviously, is that most of those centres are

located in metro areas, and we see a huge burden for regional patients. We run

a NETs patient support line, which is just our nurse who works very hard three

or four days a week on the telephone, and we see that about 40 per cent of

those calls come from regional areas. So what we would foresee is, yes, those

patients still need to be actually funded or helped to go and be seen at these

centres of excellence...[55]

3.51

The ANZCHOG National Patient and Carer Advisory Group similarly observed

that '[w]here a trial is only available interstate, participation requires

funding for interstate travel and accommodation', which is 'a huge financial

burden for interstate patients', as currently, there is no funding available.[56]

3.52

In his evidence to the committee, Mr Dan Kent of the Australasian Gastro‑Intestinal

Trials Group, stated that in New South Wales, 'we get $60 a night to travel to

a treating centre, and that really does not cover too much. It would be nice if

those costs could be encompassed within trials to get regional, rural and

remote people in'.[57]

3.53

In contrast, patients participating in a pharmaceutical clinical trial

will generally be reimbursed for travel and other costs associated with

attending appointments, unless these patients are on a cooperative group or

investigator-initiated (that is, non-commercial) trial.[58]

3.54

In its submission, Ovarian Cancer Australia recommended 'expanding

medical travel and accommodation reimbursement schemes to include registered

clinical trial participation' in order to 'overcome the reluctance displayed by

some rural and regional patients who would otherwise be ideally suited to

participate in clinical trials'.[59]

3.55

The Cancer Council Australia (CCA) and Clinical Oncology Society of

Australia (COSA) identified the lack of financial assistance as a barrier to people

living with cancer participating in clinical trials and provided the following

information about existing subsidy schemes:

Financial assistance to support travel for specialist medical

services that are not available locally are offered by state and territory governments

and administered through public hospitals. Currently, patients who choose to

participate in a clinical trial do not qualify for these schemes. For the

patient, this can reduce their available treatment options and for the

researcher, it can limit representation of the rural and remote population in

their study.

The various patient travel subsidy schemes lack flexibility

to respond to complex circumstances of individual patients, constrain decision

making and segregate eligible patients from participating in clinical trials.

Additionally, these programs are under-funded and do not meet the real life

costs of travel and accommodation. The schemes do not ensure a patient has

equitable access to all treatment options regardless of geographic location, and

in the interests of the individual and the public, the Government must

encourage participation in clinical trials for all cancer patients regardless

of geographic location.[60]

3.56

Further, CCV provided the following figure which illustrates the

variation in reimbursement for patient transport assistance across Australia.

Figure 8: A comparison of

patient travel assistance schemes across Australia[61]

3.57

In order to respond to the barriers experienced by people with cancer in

regional Victoria, CCV, together with Cancer Trials Australia and the Victorian

Cancer Agency:

...have funded a three-year project to improve cancer patient

access to clinical trials conducted at regional centres. This is one of four

projects aiming to implement innovative solutions to increasing patient access

to cancer clinical trials. It is intended that the learning from these projects

will be applied to improve access to trials at other centres.[62]

The Australian Teletrial Model

3.58

Participation in teletrials is another way in which the barriers facing people

living with cancer in regional and remote areas may be ameliorated.

3.59

A 'teletrial' encourages the 'accrual of patients to a suitable clinical

trial regardless of geography within a state' by the use of technology to

reduce the need for patients to travel to institutions where the trial is

taking place.[63]

Mr Richard Vines of Rare Cancers Australia opined that '[t]eletrials are the

only way that people in the regions...are going to get access to state-of-the-art

treatment through clinical trials, if we can somehow build a protocol and

manage that remotely'.[64]

3.60

The Australian Teletrial Model, developed by the COSA Regional and Rural

Group, and endorsed by the COSA Council:

...outlines the key considerations for increasing access to

clinical trials for people with cancer living in rural and remote communities, and

facilitate study activity across rural and remote locations...[and] has the

potential to connect research centres, and improve the rate of recruitment to

highly specialised clinical trials, including low incidence cancers.[65]

3.61

The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute advocated for the support of the

Australasian Teletrial Model, which it submitted would 'encourage accrual of

patients to a suitable clinical trial regardless of geography within a state'.[66]

3.62

In their submission, the CCA and COSA provided the following information

about the model:

The model documents a feasible and effective tele-health

strategy to increase access to clinical trials closer to home using traditional

video-conferencing technology and web based systems. In addition, the model

will aid collaboration and networking between centres. This will have a flow on

effect for delivering greater engagement in research activity, improving

adherence to evidence based practice, improving the rate of recruitment of

patients into clinical trials, reducing the disparity in cancer outcomes for

geographically dispersed populations, building clinical trial capacity, and

providing trial-related training.

Since 2011, utilisation of tele-health in the delivery of

services has increased. In the first quarter of the 2011/2012 financial year

1,809 claims relating to telehealth services were processed through Medicare

compared to 40,570 in the quarter ending 30 June 2016.[67]

3.63

The CCA and COSA suggested the establishment of site specific governance

for accredited trial sites in public institutions, to be coordinated at a state

and territory or national level, and also supported the Australian Teletrial

Model, proposing that:

...an ‘accredited trial site cluster’ could be a network of

institutions identified as having clinical trials capacity as an established

multi-centre collaborative. The level of support provided to the smaller sites

would be determined by the complexity of the trial and the clinical

capabilities at the site. Increased capacity could be provided from the primary

site to potential rural and remote locations through tele-trial models and use

of e‑technology, such as the Australasian Tele-trial Model.[68]

3.64

To illustrate the way in which the Australian Teletrial Model could

operate, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, a founding partner of the model,

provided the following example:

...patients in Victoria would have access to a trial open in

Victoria at the closest comparable hospital. ‘Teleoncology’ models of care

offer the opportunity for patients living outside major metropolitan centres to

access clinical trials closer to home, reducing the need for travel...While the

principles of operation for primary and satellite centres are the same,

site-specific governance and processes need to be developed for effective implementation.[69]

3.65

Ovarian Cancer Australia also expressed its support for the model.[70]

International trials

3.66

As noted above, the rarity of LSR cancers means that there may not be

enough patients in Australia to conduct a stand-alone clinical trial. Indeed, Professor Walker

noted that:

...the barriers to running these trials is actually obtaining

numbers for rare cancers, and that is a common thing with all rare cancers. But

if you could get all the patients with brain cancer in one centre and available

for trials then I think that would accelerate improvements in outcomes. I think

that is the difference between here and Europe.[71]

3.67

The effect of the small number of patients with LSR cancers in Australia

on the ability to establish clinical trials was also reflected in the evidence

of Dr Chris Fraser of the Australian and New Zealand Children’s

Haematology‑Oncology Group (ANZCHOG), who spoke to the importance of

international partnerships in continuing to 'provide world's best care for

Australian children with cancer':

That is because our population is very small compared to that

of North America or the larger European countries. That means that we really

cannot run these clinical trials by ourselves in this patient population; we

have to be part of these international collaborative groups. The numbers for

each of those trials are becoming smaller and smaller as the subgroups that are

eligible for those trials get smaller. For example, for a particularly

molecularly targeted drug there is only going to be a small percentage of a

certain type of tumour that will be eligible for that trial. So international

cooperation and collaboration is increasingly important.[72]

3.68

Dr Fraser noted that he informs his patients about international trials,

because '[i]f we do not tell them, the age of the internet is such that they

find out about them very quickly':

It was probably five or six years ago that you could look

parents in the eye and say, 'There really is nothing else anywhere in the world

other than what we can do here.' That is not the case sitting here today. There

are treatments available overseas, some of which have very promising results

for very high-risk leukaemias that are proving to be very efficacious.[73]

3.69

However, Dr Fraser also informed the committee about the significant

cost of participating in international trials:

For me to send a patient to North America where they could

access one of these trials costs close to $500,000 to $700,000 for them to go

and enrol on that trial. That is something that parents now in Australia have

the knowledge about and have to deal with. I guess those cells are going to

come—they are in clinical trials. We need to position ourselves to be an

attractive enough partner that we can participate in those clinical trials, not

just in those cellular therapies but other new drugs. It is a rapidly moving

field. Our model, which has served us very well, has been to put our hand up to

be part of these trials and do it on the cost of the smell of an oily rag. And

that just does not work for these new trials. We need to work out a way that we

can continue to be attractive partners and continue to have early access in the

setting of clinical trials for these new and exciting drugs, so that parents do

not have to start looking overseas.[74]

3.70

Indeed, as Professor Terrance Johns identified, access to international

trials for Australians was not a regulatory problem, but a funding problem:

Prof. Johns:...Unless the company provides money to

specifically do an arm of the trial here or do the trial itself here, they just

will not run it. I try to work in that space a bit, but I think we can sell it

better. Internationally, I think we are very competitive, especially with the

dollar at 74c. I think it could be very attractive. Americans could do trials

here at half the price that they can in the US. I am also on the management

committee for COGNO, which is the major body that oversees clinical trials for

brain cancer in Australia. We have a very coordinated system across all states

in all the major teaching hospitals where we can run these trials; and we do

run them, but—

Senator SMITH: We could run more.

Prof. Johns: we could run more. We certainly have the

capacity to run more. It is trying to engage with industry in the US and Europe

to come and do some trials here, but we could do more. It is difficult. I

applied to do a trial through the new innovation grants, and it got knocked

back because they did not see enough value for Australia moving forward. So we

are trying to do that.[75]

3.71

The issue of funding was also reflected in Mr Dustin Perry's evidence to

the committee:

There have been times when [the oncologist] has told me that

there have been clinical trials running in other countries and they are happy

to enrol patients from Australia, but with an international clinical trial, if

the principal investigator for that trial is in another country, not in

Australia, you are instantly ineligible for government funding. Because a lot

of brain cancers, particularly paediatric ones, are so rare, there is not

enough of them in Australia to run a meaningful trial at all. The way the

funding system is set up literally discriminates against brain cancers and

others that are rare.[76]

3.72

Mrs Suzanne Turpie spoke to her frustrations with accessing domestic

clinical trials for her son who has brain cancer, when there are trials

available overseas:

We seem to have a standard treatment here depending on the

cancer and then an option of a clinical trial; however, if you look overseas,

there are options for treatment. Why are those options not available here? Why

are those drugs not available here? Why do we have people here in Australia

having to crowdfund huge amounts of money—in the hundreds of thousands of

dollars—to be able to go overseas to be given the opportunity to fight for their

child's survival? They talk to a doctor here and are told: 'There's nothing

more that can be done. Go home and wait for your child to die.' This is

heart-rending, this is real and this has been said.[77]

3.73

Following the presentation of the above evidence, on 24 August 2017,

the Australian government announced that it will co‑fund, together with

the Robert Connor Dawes Foundation, ANZCHOG's AIM BRAIN,[78]

'an international collaborative trial that will enable diagnostic molecular

profiling of children with brain cancer'.[79]

The duration of the AIM BRAIN is four years, and was accessible from 31 October

2017.[80]

3.74

As discussed in chapter 2, the government also announced on the same

date $13 million of funding for competitive research grants from the MRFF

'designed to boost clinical trial registry activity with priority given to

under-researched health priorities, such as rare cancers and rare diseases'.[81]

3.75

Further, as discussed in chapter 5, on 29 October 2017, the Australian

government announced the Australian Brain Cancer Mission, a $100 million fund

to defeat brain cancer.[82]

International comparisons

3.76

The following figure illustrates the number of total oncology trials

which started between 2007 to 2016, across Australia, China, the US, the United

Kingdom (UK), Canada and South Korea.

Figure 9: Phase

II/III and III oncology trials, by year of start-up - for China, USA, UK,

Canada, South Korea and Australia[83]

3.77

As this figure illustrates, trial activity in China has tripled in less

than a decade, and will increase on the basis of the following developments:

-

Firstly, the [Chinese Food and

Drug Administration (CFDA)] is actively encouraging the conduct of China clinical

studies (including phase I, II and III studies) at the same time as the global

clinical trials program; in the past, China studies were inevitably conducted

after global programs were largely complete; and

-

Secondly, CFDA is actively

accelerating the review of Clinical Trial Applications (CTA) and in the last 24

months the number of approvals has increased from 687 (in 2014) to 3666 (in

2016). This is a five-fold increase in just two (2) years across all

therapeutic areas; we estimate about half of these approvals are in oncology.[84]

3.78

Medicines Australia informed the committee that '[t]he implication of

these developments' is such that:

...China will start to run more clinical trials as part of

global trial programs and that it will recruit quickly. For innovator medicines

companies, which must make decisions about where to place trials in the global

setting, this means that trials will most likely begin to move from slower

and/or more costly markets, to China.[85]

3.79

Ms Elizabeth de Somer of Medicines Australia explained why Australia is

no longer as competitive as other countries as a place to run clinical trials:

...other countries that have entered into the clinical trial

competition, such as China, started off at a lower base than Australia and have

rapidly met and now exceed Australia's standards. Australian standards have

more or less stagnated; we have relied on our quality and we have not improved

our costs and time for setting up and initiating clinical trials. These other

countries have; they have addressed the issues and then exceeded Australia's

benchmark.[86]

3.80

Medicines Australia submitted that the way to overcome these issues

would be to establish 'an Australian Office of Clinical Trials to enable a

national central point of contact to help drive harmonization and quality

standards across the clinical trials sector'.[87]

3.81

Regulatory improvements to clinical trials are discussed later in this

chapter.

Committee view

3.82

The committee is concerned by the barriers to accessing clinical trials

faced by people with LSR cancers, which appear to be more significant for young

people and people in regional and remote Australia. The particular challenges

for young people with LSR cancers are explored in the following chapter.

3.83

The committee is concerned that there is inconsistency in the

availability of trial information for patients through their GPs, and that

patients often resort to "Dr Google" to locate information about

clinical trials. The committee does not discourage patients from researching

possible treatments for their disease, but considers that more could be done to

promote the availability of clinical trial information amongst GPs and the

public more broadly. The committee notes that, in its evidence to the

committee, Cancer Australia conceded that such improvements could be made.

Further discussion about how to increase the awareness of GPs and the public of

LSR cancers appears in chapter 5.

3.84

The Australian government website, AustralianClinicalTrials.gov.au, has

the potential to be a valuable resource to LSR patients and their families.

However, the committee has heard that the website is complex and difficult to

navigate, requiring those searching to be familiar with precise diagnoses and

medical terms. The committee believes that improvements should be made to the

Australian clinical trials site so that is a resource and not a further barrier

to accessing trials. The CCV's clinical trial website, VCTL, which allows the

user to search by cancer type, trial type, phase, molecular target and

hospital, and filter results by gender, age, diagnosis, surgical and medical

treatment(s) already received, is a much more user-friendly and accessible

format. It also provides pop up explanations of medical terms and phrases. In

improving the Australian clinical trials website, the Australian government

should look to the VCTL as an example.

Recommendation 3

3.85

The committee recommends that the Australian government improves

AustralianClinicalTrials.gov.au so it is more accessible and user-friendly.

3.86

The committee appreciates that traditional clinical trial design

deliberately excludes certain patients so that results are rigorous and

replicable. However, patients with LSR cancers are not your "usual"

patients and maintaining the status quo is unacceptable, it is simply hindering

progress towards potential treatments and improvements in survival rates.

Innovative trial designs must be devised and allowed, with appropriate

regulation, to be pursued. The committee welcomes the approach taken by

Professor Thomas of the Garvan Institute; the committee encourages more

researchers to follow this approach where an exclusion criterion is the

availability of other trials.

3.87

While it is not appropriate for the committee or the Australian

government to dictate to researchers their scientific methods and protocols,

the committee expects that the Australian government will address regulatory

barriers which limit the availability of clinical trials for LSR cancer patients.

Regulatory barriers are addressed in detail in the following sections of this

chapter.

3.88

The committee is also deeply concerned by the difference in access to

clinical trials for people with LSR cancer living in regional and remote

Australia, in comparison with people living in metropolitan areas. This is

particularly egregious given LSR cancer patients in regional and remote areas

suffer worse five year survival rates than their metropolitan counterparts.

3.89

The committee welcomes the Australian Teletrial Model and the national

implementation guide issued by COSA.[88]

Teletrials will continue to play an important and hopefully greater role in

facilitating access to clinical trials by LSR cancer patients in regional and

remote areas. However, the committee is of the view that LSR cancer patients in

regional and remote Australia must be assisted to participate in person in

clinical trials.

3.90

The inability of LSR cancer patients participating in clinical trials to

access state and territory patient travel subsidy schemes, and the

inconsistency in the subsidies provided, are further barriers to greater

participation in clinical trials. The committee urges state and territory

governments to consider allowing patients participating in clinical trials to

access patient travel subsidy schemes and to agree on consistent subsidy rates

based on the distance and method of travel, and the average cost of accommodation

in the city in which patients are participating in the trial.

Recommendation 4

3.91

The committee recommends that state and territory governments

consider:

-

allowing low survival rate cancer patients participating in

clinical trials to access patient travel subsidy schemes; and

-

agreeing on consistent subsidy rates based on the distance and

method of travel, and the average cost of accommodation in the city in which

the patient is participating in the trial.

3.92

Finally, in respect of international trials, the committee welcomes the

participation of Australian people with LSR cancers in international clinical

trials, and is encouraged by evidence received about the number of participants

in such trials. The committee acknowledges that not only does this have a

significant impact for the individual involved in the trials, but it may also

lead to ground breaking advances for people with LSR cancers. However, participation

in international trials often comes at great cost to the patient and the

committee considers that more could be done to reduce the financial barriers to

accessing international trials for all LSR cancers. The committee would also

like to see the inclusion of Australian trial sites in collaborative international

trials increase.

Recommendation 5

3.93

The committee recommends that Australian governments improve

access to international clinical trials for people with low survival rate

cancers, including by:

-

exploring ways to reduce the financial barriers to accessing international

trials to the extent possible; and

-

further developing the existing capacity for international

collaboration on trials.

Clinical trials and regulatory issues

3.94

A number of submitters and witnesses raised regulatory issues that

impede access to trials for patients with LSR cancers.

3.95

For example, Mr Peter Orchard of CanTeen Australia observed that the

research being undertaken by individual states and individual hospitals 'is not

always well coordinated and not well shared', and therefore advocated for 'a

national direction to be laid out and national strategies to be laid down and

have funding attached to them, to try and drive changes in behaviour to a more

nationally coordinated approach'.[89]

3.96

The Children’s Cancer Research Unit (CCRU) described a clinical trial it

undertook that took 12 years to be approved.[90]

Professor Jennifer Anne Byrne informed the committee that '[a] lot of the

delays were regulatory delays', explaining that:

We would submit an application. It would go to a body based

in Canberra that would consider it. It would take a long time for us to get

comments back. We would get those comments. We would need to address them. Then

there would be another long period. The regulatory process often involves long

periods of waiting, during which time you could work on certain things in the

laboratory. You can certainly get things ready but you cannot treat a patient.

That is an issue that affects clinical trials but also other kinds of research.[91]

3.97

The following sections examine the most prevalent regulatory issues

raised during the course of the inquiry, namely:

-

barriers to gaining ethics and governance approval;

-

the differences between state and territory jurisdictions;

-

the differences between private and public hospitals; and

-

issues with respect to insurance.

Ethics and governance approval

3.98

Although it acknowledged that 'some changes have been made to streamline

ethics approval processes in Australia' for clinical trial processes, the

Children's Hospital Foundation and Australian Centre for Health Services

Innovation noted that 'governance approval processes remain largely unchanged'.[92]

3.99

The Children's Hospital Foundation and Australian Centre for Health

Services Innovation outlined the process for obtaining ethical and governance

approval for clinical trial research in Australia:

Prior to conducting a clinical trial in Australia, it is

necessary to obtain approval from a Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) to

ensure that the proposed research will be undertaken in compliance with the

National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007). After obtaining

HREC approval, it is a requirement in most Australian public hospitals and

research institutes to obtain governance approval. Governance approval is based

primarily on resourcing, budget, legal, contractual, insurance and indemnity

issues, and provides approval to conduct the clinical trial under the auspices

of the institution.[93]

3.100

It was further noted that:

Delays in obtaining governance approval of over a year or

more have been reported and primarily result from lack of clarity, consistency

and transparency of governance processes. These avoidable delays in ethical and

governance approvals are themselves unethical. In addition, most institutions

choose to wait until ethics approval is granted before commencing governance

review. It is essential that the role of the research governance office in an

institution be clearly defined and adequately resourced to ensure that approvals

can be issued in a timely manner and patients have access to much needed

treatment. Furthermore, it is important that research institutions take

responsibility for appropriate training and coordination of ethics and

governance submission/re-submission processes including provision of resources

that appropriately support the investigators wishing to undertake research.[94]

3.101

CanTeen advocated for faster approval processes for clinical trials in

hospitals through the introduction of legislation requiring hospitals to be

bound by one ethics process, and changes in the hospital governance process,

noting that:

The fact that you have to go and repeat ethics approvals in

multiple settings and get governance approval in multiple settings can really

slow down the rollout of a trial, and then, if we are talking about

international competitiveness, it does not make us internationally competitive

with the other research markets around the world.[95]

3.102

Speaking of her personal experience with the clinical trial process, Mrs Carly Gray,

whose young son passed away as a result of a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma

(DIPG), called for a national network of trials across jurisdictions and

collaboration between hospitals and research institutions, asserting that

'[p]atients cannot afford to wait for trials to begin'.[96]

State and territory jurisdictions

3.103

In respect to ethics approval, the NHMRC observed that:

The operation of ethics committees and the approval, conduct

and monitoring of research are the responsibility of the states and territories

that apply both national and state specific guidelines and legislation.[97]

3.104

The NHMRC therefore noted that although it 'is responsible for setting

the national standards for human research in Australia', such as the National

Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007)[98]

and the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research:[99]

The authorisation of human research at a particular

institution (e.g. hospital or university) and the conduct of that research by a

researcher or health practitioner are subject to a variety of national, state

and territory laws and policies.[100]

3.105

This variance in laws and policies across jurisdictions was discussed by

a variety of submitters and witnesses, who noted a lack of consistency between

states and territories with respect to clinical trials.

3.106

In its submission, Medicines Australia recognised that '[t]he systems

under which clinical trial sites in Australia are approved differ between

states and territory' and the possible difference between sites within states

for research governance, is 'an avoidable inefficiency'.[101]

It recommended implementing previous recommendations made to the government,[102]

as well as:

Establishing an Australian Office of Clinical Trials, being a

national coordination unit, to enable a national central point of contact to

help drive harmonization and quality standards across the clinical trials

sector; this would entail working collaboratively with the Commonwealth, States

and Territories[103]

3.107

Medicines Australia also outlined the effects of this on GPs and

patients:

Physicians need to have that real-time ability to find out

where trials are happening for their patients sitting there right in front of

them today. But, because it is fragmented across institutions and

jurisdictions, it is very difficult for them to do that, and, because of the

way that our primary care and our tertiary care operate, they do not have the

time to dedicate to searching for those things.[104]

3.108

The NHMRC outlined the work it has undertaken to streamline clinical trials:

between 2013 and June 2017, $6.3 million was provided to the NHMRC under two

budget measures, Expediting Clinical Trial Reform in Australia and Simplified

and Consistent Health and Medical Research, 'to develop a nationally

consistent approach to clinical trials, improve efficiency and streamline

administration and costs with the aim of positioning Australia as a world

leader in clinical research'.[105]

3.109

A key outcome resulting from this funding was a National Good Practice

Process, piloted at 16 clinical trial sites across all Australian jurisdictions

except the Northern Territory, and intended to streamline clinical trial site

assessment and authorisation phases.[106]

3.110

As part of its work streamlining clinical trials, the NHMRC also noted that

it launched AustralianClinicalTrials.gov.au in 2012, in conjunction with the

Department of Innovation, Industry and Science.[107]

3.111

In examining some of these measures, the CCA and COSA commented that

'[c]urrent governance and ethics requirements are administratively burdensome

and resource intensive, and take considerable time to satisfy'.[108]

It was submitted that the structural barriers to conducting clinical trials—which

the CCA and COSA consider the 'greatest obstacles to conducting clinical trials

in low incidence and low survival cancers', rather than lack of funding—could

be overcome by '[i]mplementing systematic changes to improve collaboration will

support the sustainability of the cancer research sector and translation of

outcomes into practice'.[109]

3.112

Roche Products Pty Limited (Roche) also identified areas where

improvements could be made with respect to streamlining clinical trials. Roche commented

that, in Australia, '[m]any approval systems remain inefficient and manual,

with wide variation and incompatibility between states and even hospitals

within the same state'.[110]

Roche continued:

Governance approval by institutions is often delayed due to

inconsistent requirements, based on a poor understanding of essential and

non-essential steps. These issues are compounded for rarer cancers where the

need to find patients and the lack of treatment centres with expertise may mean

ethics and governance delays have a greater impact.

The need for reform has been recognised by many reviews and

government committees, including the 2013 McKeon Review of medical research.

The Government has committed to addressing competitiveness through an election

announcement of $7 million to improve access to clinical trials in Australia

and through the [Council of Australian Governments] Health Council. Roche

supports urgent action to position Australia as an international research

partner of choice.[111]

3.113

Roche therefore recommended that the Australian government '[i]mplement

regulatory reforms in partnership with state and territory governments to

streamline the clinical trials approval processes'.[112]

3.114

Similarly, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute discussed the requirement

to obtain multiple ethical approvals across states, and made some

recommendations for harmonising ethics committees and streamlining governance:

The time spent obtaining multiple ethical approvals in order

to put Australian patients with the same disease on the same trial in different

states causes critical delays, with impact on patients’ opportunities to

receive treatment. Harmonisation of human research ethics committees at a

national level should be facilitated. Similarly, governance needs to be

streamlined.[113]

3.115

The NHMRC also noted other activities that it has undertaken in order to

streamline ethics approval:

-

single ethics review/ 'mutual acceptance': the National

Certification Scheme of Institutional Processes related to the Ethical Review

of Multi-centre research commenced in 2010, and NHMRC has certified 44

institutions under this scheme. Additionally, Departments of Health in all

states and territories, bar the Northern Territory and Tasmania, are party to

an Memorandum of Understanding for the National Mutual Acceptance 'of ethics

and scientific review of clinical trials conducted in each of the participating

jurisdictions’ public health organisations', which is restricted to mutual

acceptance between approved state health organisation Human Research Ethics

Committees;[114]

and

-

the Human Research Ethics Application: this replaces the

National Ethics Application Form (NEAF), and aims 'to facilitate efficient and

effective ethics review for research involving humans (i.e. not limited to

clinical trials).[115]

It was adopted by the IT platform currently used by the health systems in New

South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory

'for the management of ethics review and site approval and authorisation';

however, 'timelines for ethics approval may still vary both within and between

the public and private health sectors'.[116]

3.116

Regardless of these changes, the committee heard that in practice,

ethics approval is not straightforward. For example, speaking to the time it

takes to set up a clinical trial, Mrs Helen Aunedi of Roche informed the

committee that 'it comes down to delays in our budget and contractual

negotiations', noting that there are '200 accredited ethics committees in

Australia'.[117]

Mrs Aunedi advocated for 'a centralised committee that can review and approve

these clinical studies so we can start quicker', but noted that there is also a

delay at the site level, because of the contract, the indemnity and the

insurance:

These are all core templates, so we do not really understand

why the institutions are spending so much time negotiating on these issues. But

I think, simply, if we could fix that aspect, and then we could perhaps use the

national office to promote more of this mutual acceptance. We already have it

in place. We just need to have it at the federal level. So it would be great to

get support from this inquiry to be able to move that forward.[118]

Public versus private hospitals

3.117

The differences between states and territories in respect of ethics

approval and conducting clinical trials also arise in respect of public versus

private hospitals.

3.118

For example, Ms Emma Raymond of Wesley Medical Research informed the

committee that the process for ethics approval in a private hospital is far

simpler than the process in public hospitals:

In the private sector, you know who your ethics committee is.

It is very simple: you know where the forms are, you submit them, and it is

done. If they have any questions they will come and ask you. When it goes

across to the public system, they have a thing called a NEAF, which is supposed

to allow for an easy application—one large application, and then site-specific

applications for each hospital. But it does not work that way. I did a NEAF

that was approved—one site was approved. I used the same documents for another

Queensland Health hospital and we had to rewrite everything ...

A NEAF...has about 61 pages where you answer a lot of questions

and upload documents about the research, and then, for each hospital site that

you want access to, you then have to do another application, which is then looked

at by each hospital's ethics committee. Once it is approved there, it then goes

to the governance committee. The problem arises if you have not filled

something out correctly. At one point I had the wrong number on a page. They do

not tell you that; they just put it on hold and then when they finally get back

to you have to resubmit it again, but you have missed the next deadline for the

ethics committee, so then it gets held over again and then, if it gets to

governance, and they do not like the paperwork, it gets held up again. That is

before you even start the research.[119]

3.119

Ms Raymond also observed that there are different time pressures on

clinicians in public, compared to private, hospitals:

...in the private sector there is more of a focus on clinician

research. In the public sector they are too busy and there are too many people

involved from start to finish. Sometimes, the clinician who is doing the care

will not even know that they have gone on to have treatment because it is just

such a busy, fast-paced scenario.[120]

3.120

Ms Delaine Smith of the ALLG informed the committee that private

institutions 'are traditionally not substantial contributors to investigator

initiated clinical trials', explaining:

There is little to almost no incentive for private facilities

or clinicians to have their patients participate in clinical trials. This

impacts adversely on the rate of patient accrual to clinical trials. The second

point is that, additionally, there is no incentive or support from private

health insurers to have their patients participate in clinical trial

research—it is simply not there. One could argue that it is even a greater

priority for the private sector to participate and champion research that

inevitably will have the potential to bring about healthcare efficiencies and

cost savings.[121]

3.121

Professor Andrew Roberts, also of the ALLG, provided a further

explanation:

It is quite clear that to be

involved in a clinical trial requires extra care, extra time, extra resources

and therefore extra costs. Clearly that affects issues around reimbursement,

whether that is through private or government. Ultimately, to participate in

clinical research, the patient, the doctor, the sponsor of the trial and our

health system are invested, and it is a question of whether they are clear

about that and whether there is an alignment of purpose.[122]

3.122

The ALLG suggested that the way in which to overcome the obstacle that

clinicians are time poor, which can impact matters such as timely access to

information about clinical trials, could be to encourage models that encourage

public/ private partnerships.[123]

The ALLG also recommended enabling collaboration between public and private

institutions by engaging with insurance companies and the private health care

sector, and implementing 'national clinical trial uptake across public and

private hospitals' as ways to improve survival rates by establishing Key

Performance Indicators (KPIs) for hospitals regarding clinical trial

participation, their uptake of patients to clinical trials, and creating 'a

culture of positive benefit'.[124]

3.123

CanTeen Australia also proposed collaboration across institutions,

recommending the establishment and operation of national low survival cancer

trial networks which would:

...operate across multiple hospital boundaries (including

across local health districts, public and private hospitals and adult and

paediatric settings), assure rapid trial initiation, consistent, cost effective

and timely ethics, governance and other relevant approvals, rapid and targeted

access to patients and consistent monitoring processes and standards.[125]

Insurance

3.124

In evidence to the committee, CanTeen highlighted the importance and

benefits of exploring options around a national insurance scheme covering

clinical trials which would alleviate the burden that individual hospitals

currently face by having to seek coverage for a given trial:

... in terms of insurance: again, could there be a national

insurance scheme that covers trials so that we do not have this business of

every hospital having to go to see whether their particular insurer will cover

them for this trial?

Just in terms of that insurance process alone: that gets

replicated in every hospital, let alone them needing to ask about the impacts

on their staffing or their budget. It is an understandable process that they

have to do, but to take four or five months for it is the part that does not

seem to be valid, really. If we are really keen about getting patients into

trials quickly and getting good research happening, we need to make those times

shorter.[126]

3.125

In response to this suggestion, Professor Anne Kelso of the NHMRC stated

that it was outside of the NHMRC's remit to do such work, and that 'unless we

were tasked and funded to do a particular project; it's otherwise not within

the remit of NHMRC's activities'.[127]

Committee view

3.126

While there have been recent changes to improve streamlining of clinical

trial ethics approval, the evidence presented to the committee indicates that differences

in ethics and governance approval processes between states and territories, and

private and public hospitals continue to delay and in some instances discourage

trials or trials across multiple sites.

3.127

The committee welcomes suggestions from various submitters and

witnesses, such as removing the requirement to obtain ethics and governance

approval for each individual trial site; the establishment of an Australian

Office of Clinical Trials to be a national coordination unit and national

central point of contact to help drive harmonization and quality standards;

further regulatory reforms to streamline approvals processes; and facilitating

better collaboration between private and public institutions.

3.128

The committee recommends that Australian governments address the

remaining barriers arising from differences in ethics and governance approval

processes as a matter of priority, and in doing so give serious consideration

to the proposals recommended to this inquiry.

Recommendation 6

3.129

The committee recommends that Australian governments, as a

priority, further streamline ethics and governance approval processes for

clinical trials, particularly where those processes differ between states and

territories, and public and private research institutions.

3.130

Further, the committee acknowledges the work that the NHMRC has done to

reduce unnecessary regulatory barriers with respect to ethics processes, and

while it recognises that some processes are beyond the scope of the NHMRC, the

committee considers that the NHMRC could make further changes in order to

eliminate those existing, significant regulatory delays.

3.131

Specifically, the committee considers that the NHMRC could develop a

standard template and associated guidelines, including timeframes, for ethics

and other governance approvals that could be adopted by every state and

territory. This in turn could allow for the approval from one institution to

lead to automatic approval at any other institution.

Recommendation 7

3.132