Funding for research into low survival rate cancers

2.1

The impact of effective research investment is clearly demonstrated by

the increased survival rates for people with certain cancers, such as breast

and prostate cancer.[1]

Funding for cancer research comes from various sources, including the National

Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), which, as discussed further below,

recently restructured its grants program.[2]

2.2

This chapter commences by defining cancer research and then examines the

various sources of funding for such research, focussing specifically on

government funding through the NHMRC, Cancer Australia and the newly

established Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF), as well as philanthropic and pharmaceutical

funding.

2.3

The chapter then provides some context to the challenges facing funding

for research into low survival rate (LSR) cancers by providing an overview of

the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), the Pharmaceutical Benefits

Advisory Committee (PBAC) and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).

The chapter concludes by examining the available funding for LSR cancers.

Cancer research

2.4

In 2016, Cancer Australia published a report into the funding for cancer

research projects in Australia from 2016–2018, using data from grants awarded to

these projects to the end of July 2015.[3]

2.5

This report identified that the Australian government is currently

funding 74 per cent, or $187 million, of the $252 million that has

been provided to 589 individual research projects for the period 2016–2018.[4]

Ninety five per cent of these research projects are funded by a single source.[5]

2.6

The following figure illustrates how cancer research funding for this

period has been allocated by reference to the Common Scientific Outline (CSO),

a system which 'uses easily applied terminology to describe and classify

research by where it best fits into the cancer research continuum'.[6]

Figure 1: The national pattern of cancer research funding

in 2016 to 2018[7]

2.7

As can be seen in Figure 2, Cancer Australia also classified the cancer

research funding during this period by reference to a system developed by the United

States (US) National Cancer Institute, which is used to identify translational

elements within CSO sub‑categories.[8]

These categories are defined as follows:

-

Not Translational – basic

research;

-

Translational/Early – the

translational process that follows fundamental discovery and precedes

definitive, late-stage trials;

-

Translational/Clinical – research

at the clinical application end of the translational spectrum;

-

Translational/General – research

where difficulty in separating early and late translation/clinical research;

-

Translational/Patient-oriented –

research focussed on needs in the area of patient care and survivorship[9]

2.8

This figure illustrates that translational research in the clinical,

general and patient‑oriented categories will receive less than 10 per

cent funding each for the 2016–2018 period.

Figure 2: Percentage of funding to cancer research

projects and programs classified by translation categories[10]

2.9

The lack of funding for the clinical stage of research was discussed by

the Low Cancer Survivals Alliance (LCSA), which submitted that '[t]here is a

lack of leadership by state and federal governments to encourage health

services to support clinical trial research':

Funding bodies such as the NHMRC traditionally do not support

translational research, therefore these breakthroughs are often not capitalised

on and further developed. Often funding for basic research is preferred over

clinical trials, as it can have more immediate results. As an example, in

February 2017 an incredible breakthrough was published in the international

journal Nature for the genome sequencing of pancreatic nets, led by Melbourne

University researchers. This research now needs to be supported and built upon,

in order for it to have an impact on patient outcomes.[11]

2.10

Indeed, The Unicorn Foundation similarly identified that 'the current

NHMRC model does not actively support translational research in low survival

cancers' and advocated for 'a new model of funding' for the NHMRC and support

for clinical trials for LSR cancers.[12]

2.11

However, in her evidence to the committee, Professor Anne Kelso of the

NHMRC made clear that her organisation funds discovery through to translational

research:

The NHMRC is interested in funding research that covers the

whole spectrum from discovery research, which might help us to understand the

origins of disease and also the origins of health, but we seek to fund across

the full spectrum from discovery through to translation into better health

care. We fund many clinical trials that assist in that translation of new

ideas, new discoveries, into better health care. We also fund research to

improve health services across the board. So there is a very broad range of

research that NHMRC funds, and some of it is very directly translational and

some of it is earlier stage.[13]

2.12

Despite this, Professor Stephen Fox identified a 'tension between true

translational clinical work and some of the basic discovery work', suggesting

how funding of clinical trials could jeopardise funding of discovery research:

There are the basic NHMRC studies, which are very much

discovery-type stuff, and then there is the other end of the spectrum, which is

the clinical trials-type activity. I think the clinical trials activity is

usually fairly explicit and straightforward in what the aims are. I think there

is an understanding behind that. The issue is that running a clinical trial, as

I am sure you have heard, is an incredibly expensive endeavour and takes a

large slice of the budget. So you only have to, I suppose, fund a few of those

and you have basically taken a huge chunk of your budget away from the

discovery sector.[14]

2.13

Advocating for a balance between discovery and translational research

funding, Professor Manuel Graeber identified that currently, 'there is no

balance' and further, that:

...translational outcomes, to some extent, represent marketing

speak. Politicians must be aware of the power they have. If the decision is

made to favour an area then everybody, in the current funding climate, will

jump at this. Administrators will and researchers have to follow but that is

wrong. Researchers are the ones that are supposed to come up with the

innovations. They are not being listened to often nowadays, because of the

way—based on a global trend—science has changed. In the old days it was just

idealists working somewhere without pay—some still work without pay today.

Generally institutions cannot afford it and that is the big problem—the

research dollars. I cost the university money. Teaching is much more

attractive, but, of course, it would be living on intellectual credit if we

would not support the research. That is the future.

I think it is really important how this is marketed—directed

by the politicians. Translational outcomes flies well with politicians, but it

is important to really look at the substance. What is really being produced?

Where is innovation coming from? How can we enable that? It will not come just

through some policy decisions. Scientists are not motivated to engage in it,

because it is like the 'fashion scientist', who makes a career by being in

policy making. We are about innovation. We are supposed to find new things that

are reproducible. That is our job. It is not to compete with politicians

implementing policies. That is my personal view, so do not blame it on the

university. That is my view, and I am happy to defend it.[15]

2.14

In its report, Cancer Australia concluded by identifying the following

opportunities for future strategic investment in cancer research, some of which

will be addressed in chapter 5 of this report:

-

targeted research investment by tumour site;

-

targeted research investment by research category;

-

translational research; and

-

research collaborations.[16]

Sources of funding

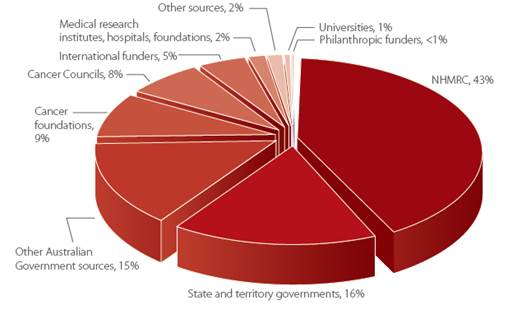

2.15

There are many different government and non-government sources of

funding for medical research. Although government funding can include funding

directly from the Department of Health (DoH), this chapter exclusively examines

funding from the NHMRC, Cancer Australia and the MRFF, which were the

government sources most frequently referred to in submissions and evidence to

the committee. At points throughout this report, there may be references to

other sources of government funding.

2.16

In addition to government funding for medical research, a significant

amount of funding is also provided by non‑government sources,

particularly philanthropic and pharmaceutical sources. For this reason, this

section also briefly examines these sources of funding.

The National Health and Medical

Research Council

2.17

The function of the NHMRC, a statutory body which operates pursuant to

the National Health and Medical Research Council Act 1992 (NHMRC Act), is

to assist the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the NHMRC, a position currently

held by Professor Kelso, in the performance of her functions.[17]

These functions are:

- in the name of the NHMRC, to inquire into, issue

guidelines on, and advise the community on, matters relating to:

- the improvement of health;

and

- the prevention, diagnosis

and treatment of disease; and

- the provision of health

care; and

- public health research and

medical research; and

- ethical issues relating to

health; and

- to advise, and make recommendations to, the

Commonwealth, the States and the Territories on the matters referred to in

paragraph (a); and

- to make recommendations to the Minister on expenditure:

- on public health research and

training; and

- on medical research and

training;

including recommendations on the

application of the Account; and

- any other functions conferred on the CEO in writing by

the Minister; and

- any other functions conferred on the CEO by this Act,

the regulations or any other law; and

- any functions incidental to any of the foregoing.[18]

2.18

The minister may also delegate additional functions to the CEO.[19]

2.19

The Council of the NHMRC[20]

provides advice to the CEO in relation to the performance of these functions,

and also performs any other functions conferred by the minister, the NHMRC Act,

its regulations, or any other law.[21]

2.20

Mr Greg Mullins of Research Australia observed that NHMRC funding has been

'effectively flatlining in recent years'[22]

and spoke to the positive effects of adequately funding the NHMRC:

One of the things that happened with NHMRC funding in the

period from 2000 to about 2010 was that the funding was doubled, and then it

was doubled again. That was a great outcome; it was really good news for the

sector. What it has done is attract a whole lot more people into the field. We

are seeing more people undertaking PhDs in this area. I think the latest budget

figures were predicting that Australia-wide we were going to move from 9½

thousand PhD completions last year to 12½ thousand by 2019-20. So we are seeing

an increasing number of people coming into this area.[23]

2.21

However, Mr Mullins opined that the availability of NHMRC funding to

support these researchers and their work is lacking, which is consequently

reflected 'in things like the drop in the success rates with NHMRC funding'.[24]

The difficulty of securing NHMRC funding was also identified by Dr Bryan Day,

who informed the committee that 'the competition in the current NHMRC funding

pool is incredibly high, because the pot of money is small'.[25]

The NHMRC's previous approach to

funding

2.22

The NHMRC is 'the largest single funder of health and medical research

in Australia', covering 'the breadth of health and medical research needs'.[26]

In its submission, the NHMRC set out the process by which it considers funding

applications:

Consistent with the NHMRC Act, NHMRC focuses on the relevance

of research proposals for health, rather than defining ‘health and medical

research’ as a set of research disciplines. NHMRC will fund research in any or

all areas relevant to health. It will also accept grant applications in any

research discipline and applicants are provided with an opportunity within

their application to explain how their research will lead to improved outcomes

in health.

Most NHMRC funding is awarded in response to

investigator-initiated applications in which the research is conceived and

developed by the researchers. A smaller proportion of funding is directed to

specific areas of unmet need, e.g., through Targeted Calls for Research,

special Centres of Research Excellence, Partnership Centres and some

Partnership Projects.

The primary criterion for all funding decisions is excellence.

NHMRC relies on review by independent experts to identify the best

applications, based on the significance of the research, the quality and

feasibility of the research proposal, and the track record of the

investigators. Rigorous processes of expert review ensure transparency, probity

and fairness.

When applications for funding are received, the office of

NHMRC manages the expert assessment of applications by independent experts. The

outcomes of expert review are used to determine which applications will be

recommended for funding. NHMRC’s [Research Committee] recommends those

applications to be funded through NHMRC Council to the CEO who submits them for

approval to the Minister with portfolio responsibility for NHMRC.[27]

2.23

The NHMRC also outlined its capacity to direct funding to priorities, as

required:

NHMRC’s range of funding schemes also provides the

flexibility necessary for targeting research and capacity building in key areas

of need in the health system. Each year NHMRC sets aside a component of the [Medical

Research Endowment Account] to address identified priorities. Priorities are

often implemented through additional funding provided for existing NHMRC

schemes, such as the Centres of Research Excellence scheme.

Each year, a small proportion of the total annual expenditure

budget is set aside to fund priority research areas through its Targeted Calls

for Research (TCR) funding program. A TCR is a specific funding mechanism that

invites grant applications to address a specific health issue. NHMRC may

initiate a TCR to address additional major issues that arise or in cases where

substantial gaps in evidence are identified. The aim of a TCR is to stimulate

or greatly advance research in a particular area of health and medical science

that will benefit the health of Australians. Through the TCR program, NHMRC has

an opportunity to identify and subsequently fund emerging health problems in

Australia.[28]

2.24

In respect of cancer funding in particular, the NHMRC stated that it 'is

the biggest funder of cancer research in Australia, accounting for 56% of all

funding nationwide'.[29]

The allocation of cancer research funding:

...is based on the review of each grant against a range of

investigator-provided data classifications including Burden of Disease

allocations, fields of research, keywords, grant titles and media summaries.

Many grants address more than one cancer type and in these cases the full value

of each is attributed to each relevant cancer type.[30]

2.25

The following table sets out the NHMRC's funding for cancer research for

the period 2012 to 2016, across all grant types, where the allocation of

funding is:

...based on the review of each individual grant against a range

of investigator provided data classifications including Burden of Disease

allocations, fields of research, keywords, grant titles and media summaries.

Many grants address more than one cancer type and in these cases the full value

of each is attributed to each relevant cancer type.[31]

Table 1: NHMRC cancer

research expenditure 2012 to 2016[32]

| Cancer Type |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

Total |

| Leukaemia |

$23,803,468 |

$19,769,414 |

$24,096,017 |

$25,068,518 |

$23,704,073 |

$116,441,490 |

| Breast

Cancer |

$24,803,186 |

$21,852,140 |

$20,508,426 |

$23,924,737 |

$21,469,127 |

$112,557,616 |

| Colorectal

Cancer |

$17,110,467 |

$14,400,726 |

$11,047,089 |

$13,427,898 |

$12,371,421 |

$68,357,601 |

| Childhood

Cancer |

$13,873,871 |

$12,425,114 |

$11,839,850 |

$12,219,439 |

$10,358,657 |

$60,716,931 |

| Melanoma |

$11,083,287 |

$11,012,931 |

$11,943,557 |

$13,145,930 |

$13,403,015 |

$60,588,720 |

| Prostate

Cancer |

$15,714,971 |

$10,777,957 |

$8,299,874 |

$8,895,471 |

$8,458,090 |

$52,146,363 |

| Hodgkin’s

Lymphoma |

$10,448,532 |

$8,507,097 |

$8,081,885 |

$8,088,540 |

$6,100,138 |

$41,226,192 |

| Ovarian

Cancer |

$11,516,436 |

$10,569,137 |

$7,690,016 |

$4,393,454 |

$4,701,048 |

$38,870,091 |

| Brain

Cancer |

$7,973,145 |

$7,207,891 |

$8,341,513 |

$8,469,035 |

$6,630,739 |

$38,622,323 |

| Lung

Cancer |

$5,822,566 |

$6,795,275 |

$7,610,659 |

$7,988,644 |

$7,769,633 |

$35,986,777 |

| Pancreatic

Cancer |

$9,812,427 |

$8,923,906 |

$6,841,808 |

$3,653,131 |

$4,117,523 |

$33,348,795 |

| Multiple

Myeloma |

$7,055,307 |

$6,079,353 |

$5,654,967 |

$5,851,116 |

$4,769,828 |

$29,410,571 |

| Liver

Cancer |

$3,209,094 |

$3,812,146 |

$5,470,925 |

$5,275,872 |

$4,455,742 |

$22,223,779 |

| Stomach

Cancer |

$3,731,366 |

$3,716,477 |

$2,662,717 |

$3,608,741 |

$4,695,318 |

$18,414,619 |

| Mesothelioma |

$1,914,182 |

$1,696,954 |

$2,097,639 |

$3,117,450 |

$2,142,460 |

$10,968,685 |

| Bone

Cancer |

$2,515,135 |

$1,986,772 |

$2,202,010 |

$2,205,394 |

$1,383,337 |

$10,292,648 |

| Oesophageal

Cancer |

$3,059,316 |

$2,667,775 |

$1,781,589 |

$1,524,016 |

$1,148,474 |

$10,181,170 |

| Endometrial

Cancer |

$2,362,829 |

$2,039,453 |

$1,587,515 |

$1,474,190 |

$1,420,730 |

$8,884,717 |

| Non-Hodgkin’s

Lymphoma |

$1,488,384 |

$1,533,322 |

$2,166,269 |

$2,210,672 |

$1,433,272 |

$8,831,919 |

| Head

and Neck Cancers |

$1,917,637 |

$1,929,367 |

$1,691,935 |

$1,195,252 |

$1,003,233 |

$7,737,424 |

| Cervical

Cancer |

$1,131,369 |

$1,442,060 |

$1,909,510 |

$1,040,493 |

$1,308,283 |

$6,831,715 |

| Testicular

Cancer |

$1,453,958 |

$1,602,101 |

$1,183,460 |

$1,194,662 |

$895,991 |

$6,330,172 |

| Kidney

Cancer |

$1,340,442 |

$852,278 |

$667,439 |

$420,627 |

$321,571 |

$3,602,357 |

| Bladder

Cancer |

$464,861 |

$467,727 |

$537,361 |

$304,437 |

$198,704 |

$1,973,090 |

| Thyroid

Cancer |

|

$97,733 |

$428,827 |

$551,373 |

$535,646 |

$1,613,579 |

| Vulvar

Cancer |

$439,249 |

|

$397,276 |

$383,721 |

$373,346 |

$1,593,592 |

| Adrenal

Cancer |

$295,384 |

$250,452 |

$119,529 |

$165,361 |

$477,340 |

$1,308,066 |

| Anal

Cancer |

$202,025 |

$132,337 |

$122,911 |

$60,173 |

|

$517,446 |

| Eye

Cancer |

$188,285 |

|

|

|

$36,134 |

$224,419 |

| Parathyroid

Cancer |

|

|

|

$124,531 |

|

$124,531 |

| Pituitary

Cancer |

|

$17,949 |

$38,437 |

$13,335 |

$21,197 |

$90,918 |

2.26

The NHMRC also provided the following additional table comparing its

research expenditure with incidence, mortality and survival rates, for 'all

persons', except in the case of the following gender-specific cancers:

cervical, ovarian, uterine, prostate and testicular cancers.[33]

The data for cancer incidence, mortality and survival rates were sourced from

the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW).[34]

Table 2: NHMRC cancer research expenditure comparison

with incidence, mortality and survival rates[35]

| Cancer

Type |

NHMRC

Expenditure 2012 to 2016 |

2013

Age-standardised incidence rate |

2014

Age-standardised 5 yr mortality rate |

Five-year

relative survival from selected cancers, 2009–2013 (%) |

| Leukaemia |

$116,441,490 |

13.3 |

6.2 |

- |

| Breast

Cancer |

$112,557,616 |

63.6 |

10.5 |

90.2 |

| Colorectal

Cancer |

$68,357,601 |

57.7 |

14.9 |

68.7 |

| Melanoma |

$60,588,720 |

50.3 |

5.5 |

90.4 |

| Prostate

Cancer |

$52,146,363 |

151.3 |

25.8 |

94.5 |

| Hodgkins

Lymphoma |

$41,226,192 |

2.6 |

0.4 |

87.5 |

| Ovarian

Cancer |

$38,870,091 |

10.6 |

6.8 |

44.4 |

| Brain

Cancer |

$38,622,323 |

6.5 |

5.3 |

22.1 |

| Lung

Cancer |

$35,986,777 |

42.6 |

30.5 |

15.8 |

| Pancreatic

Cancer |

$33,348,795 |

10.9 |

9.3 |

7.7 |

| Multiple

Myeloma |

$29,410,571 |

6.3 |

3.3 |

48.5 |

| Liver

Cancer |

$22,223,779 |

6.9 |

6.4 |

17.3 |

| Stomach Cancer |

$18,414,619 |

8.1 |

4.2 |

28.5 |

| Uterine

Cancer |

$12,351,703 |

18.6 |

3.4 |

83.2 |

| Mesothelioma |

$10,968,685 |

2.7 |

2.6 |

5.8 |

| Bone

Cancer |

$10,292,648 |

0.8 |

0.4 |

69.7 |

| Oesophageal

Cancer |

$10,181,170 |

5.4 |

4.4 |

20.1 |

| Non-Hodgkins

Lymphoma |

$8,831,919 |

19.4 |

5.5 |

74.3 |

| Head

and Neck Cancers |

$7,737,424 |

17.2 |

3.8 |

- |

| Cervical

Cancer |

$6,831,715 |

6.8 |

1.7 |

72.1 |

| Testicular

Cancer |

$6,330,172 |

6.4 |

0.2 |

97.9 |

| Kidney

Cancer |

$3,602,357 |

11.9 |

3.4 |

74.9 |

| Bladder

Cancer |

$1,973,090 |

9.7 |

3.7 |

53.3 |

| Thyroid

Cancer |

$1,613,579 |

10.6 |

0.5 |

96.1 |

| Anal

Cancer |

$517,446 |

1.5 |

0.4 |

67.1 |

Criticisms of the previous approach

with respect to funding research into LSR cancers

2.27

A number of submitters and witnesses criticised the former NHMRC funding

model—in place up until the minister's announcement on 25 May 2017—and its 'one

size fits all' approach[36]

asserting that it disadvantages,[37]

or is biased against,[38]

researchers into LSR cancers.

2.28

For example, the Children's Cancer Research Unit (CCRU) of The

Children's Hospital at Westmead outlined some issues that arise with respect to

receiving NHMRC grants for research into LSR cancers:

We believe that characteristics of low survival rate cancers

can make it more difficult for associated research grant proposals to be

considered “well designed (or to have) a near flawless design”. The fact that a

particular cancer is characterised by poor survival rates can reflect a more

limited research base, leading to less scientific knowledge. This can mean a

greater need for more open-ended research grant applications seeking to (for

example) identify treatment targets, or biomarkers of response. However, these

more open-ended proposals can be viewed by grant review committees and

reviewers as “fishing expeditions” that may be less likely to be considered to

have “objectives that are well-defined, highly coherent and strongly developed

(and be either) well designed (or have) a near flawless design”. Similarly, low

survival rate cancers may have fewer experimental models (cell lines, mouse and

other animal models) available for study. It can also be challenging to access

statistically informative and representative sample cohorts, or patient cohorts

for clinical trials. Reduced resources for research could therefore also lead

to reduced “scientific quality” and “significance and innovation” scores for

NHMRC project grant applications, as well as negatively impacting the team’s

“track record”. One of the most problematic issues is how the determination of

“an issue of great importance to human health” is made, as this judgement can

clearly be made according to various criteria. The association between lower

cancer incidence and reduced patient survival can mean that research into some

cancers with poor outcomes could be viewed as less “important”.[39]

2.29

The LCSA similarly outlined how this funding program disadvantages

'researchers investigating low survival cancers, who generally have less pilot

data or proof of concepts than those researching more common cancers with

better outcomes'.[40]

It submitted that '[t]he NHMRC is not a reliable method for many researchers

wishing to secure research funding for low survival cancers to get worthwhile

projects off the ground'.[41]

2.30

Dr Marina Pajic informed the committee of the difficulties with

obtaining NHMRC funding based on her experiences:

In order to get something to the standard that NHMRC requires

to really be competitive, that study pretty much needs to be 80 per cent

complete. You need to convince these reviewers that this grant is foolproof,

that it will work, and that is not really what research should be all about. It

is all about figuring out that, actually, maybe something will not work. That

in itself may then be an interesting result that you take further and develop

new ideas around. I guess philanthropic money is really where those sorts of

studies are currently done, and there is just not a lot of that money around. I

am talking about pancreatic cancer researchers in general. I am fortunate

enough to have the support of the Garvan Research Foundation, so I have been

able to get my studies to that level to get NHMRC and Cancer Australia funding

on occasion.[42]

2.31

The Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group (ALLG) noted that, in its

experience, the NHMRC model in place prior to 25 May 2017 'favour[ed] those

cancers that attract more non-government funding'. The ALLG observed that those

cancers which attract non-government funding, have elements of:

-

public “popularity” and

prominence;

-

commerciality i.e. where industry

has a vested interest in a commercial pipeline; and

-

potential commercialisation of

intellectual property.[43]

2.32

However, in its submission, Research Australia suggested another reason

why this correlation between non-government and NHMRC funding exists: that is, '[t]he

NHMRC typically only funds the direct costs of research, leaving the

organisation undertaking the research to meet the indirect research costs from

other sources', such as philanthropic funding.[44]

An explanation of this reasoning was provided:

As a consequence of the continuing under funding of indirect

research costs, researchers need to find other sources of funding for the

balance of the indirect costs. In the case of universities and medical research

institutes, these sources include their own funds and philanthropic funding;

some of the latter are directed towards supporting research into specific

diseases. The availability of funding from philanthropic sources to meet the

indirect costs of research can influence the types of research that an

organisation will undertake and the applications that it will make to the NHMRC

for funding. To the extent that there is more funding available from non‑government

sources to support research into a particular disease, this can lead to more

applications to the NHMRC for funding in that area. This can favour research

into areas that have strong philanthropic support. Conversely, areas of

research that receive relatively less funding from non‑government sources

can be less successful in the open, competitive grant schemes administered by

the NHMRC and other government funding agencies.[45]

2.33

In its submission to this committee, the Victorian Comprehensive Cancer

Centre (VCCC) also discussed the significance of philanthropic funding:

Philanthropic sources of funding are divided between patient

support services and grants for research and these funds can make a significant

impact on preliminary research activity. Higher levels of philanthropic funding

for the various charitable cancer foundations has typically been related to (i)

higher survival rate cancers, where survivors are active in fundraising to

“give back” to the field, and (ii) high incidence cancers, where a large pool

of affected individuals and families can be leveraged for philanthropic

donations. Low incidence and low survival cancers do not have these resources

and moreover, there may be social stigma related to the cancers, e.g. lung and

brain cancers.[46]

2.34

Although the VCCC did not consider that there was any 'systemic bias' in

the NHMRC model, asserting that '[t]he process of scoring to assess NHMRC

applications is rigorous and robust',[47]

it was acknowledged that:

...the success rates of applications reflect the far greater

pool of resources available to researchers working in certain areas, e.g.

breast cancer, that supports them being successful researchers who will in turn

have greater success at NHRMC, i.e. it is the funding of preliminary work,

which requires scientists, expendables and infrastructure, that results in a

high-scoring funding application. It is also this funding that can enhance

track record and demonstrate that a research group can complete the project.

This tends to be in the cancer types that have already shown research success

and improved outcomes (which are more noteworthy than failures in poor outcome

diseases), further compounding the disparity between highly-funded and

low-funded research.[48]

2.35

Research Australia therefore proposed that the government should fully

fund indirect costs of research on the basis that this:

...would allow more philanthropic funding to be directed to

support novel early stage research and early career researchers, in turn

helping to improve their chances of securing Australian Government competitive

grant funding.[49]

Changes to the NHMRC funding structure

2.36

On 28 January 2016, the NHMRC CEO, Professor Kelso, announced 'an over‑arching

review of the structure of NHMRC's grant program',[50]

which was considered necessary for a number of reasons.

2.37

One reason was the decrease in funding for most of the NHMRC's funding

schemes from 2012 to 2015,[51]

which created 'a hypercompetitive environment, and [maybe] lead to research

proposals targeting low survival rate cancers being increasingly

disadvantaged'.[52]

This is illustrated by the following example of the Project Grants scheme at

Figure 3.

Figure 3: Rising

application numbers and falling funding rates in the Project Grants scheme,

1980 – 2015[53]

2.38

Further, there was also 'widespread concern that the high volume of

applications for NHMRC funding is having a range of negative effects on

Australian health and medical research' including that:

-

Researchers are spending a

substantial period each year preparing grant applications that will not be

funded, despite many being of sufficient quality to be funded.

-

The load on peer reviewers (most

of whom are themselves researchers) has become excessive for the number of

grants funded.

-

Early and mid-career researchers,

especially women, may feel discouraged from pursuing a research career.

-

Applicants are more likely to

propose, and peer reviewers are more likely to favour, “safe” research to the

detriment of innovation.

-

The low likelihood of funding is

driving further increases in application numbers as researchers seek to improve

their chances of obtaining a grant, exacerbating the situation.[54]

2.39

The NHMRC’s Research Committee, after considering a range of options,

reached the conclusion 'that commonly suggested changes to existing funding

schemes would not achieve a sufficient reduction in application numbers' that

would overcome such issues.[55]

2.40

Indeed, in 2015, many submitters to the NHMRC's public consultation on

Current and Emerging Issues for NHMRC Fellowship Schemes called for an overarching

review of the NHMRC's grant program.[56]

2.41

The review therefore had the aim of determining:

...whether the suite of funding schemes can be streamlined and

adapted to current circumstances, while continuing to support the best Australian

research and researchers for the benefit of human health.[57]

2.42

On 14 July 2016, the NHMRC released a public consultation paper on the review,

and public forums were also held in several capital cities.[58]

2.43

During the process of the NHMRC's review into its funding structure, an Expert Advisory

Group 'provided advice and assistance to NHMRC in examining the current grant

program and possible alternative models'.[59]

The CEO subsequently drew on its advice in formulating the new funding

structure, as well as that of the NHMRC Research Committee, the NHMRC Council,

Health Translation Advisory Committee, Health Innovation Advisory Committee and

the Principal Committee Indigenous Caucus.[60]

2.44

The NHMRC's restructured funding program, an overview of which appears

at Table 3, was announced on 25 May 2017[61]

and aims to:

-

encourage greater creativity and

innovation in research,

-

provide opportunities for talented

researchers at all career stages to contribute to the improvement of human

health, and

-

minimise the burden on researchers

of application and peer review so that researchers can spend more time

producing high quality research.[62]

2.45

In summary:

The restructured program will comprise Investigator Grants,

Synergy Grants, Ideas Grants and Strategic and Leveraging Grants. Limits will

also be placed on the number of grants an individual researcher can apply for

or hold.

Investigator Grants, Synergy Grants and Ideas Grants will

replace Fellowships, Program Grants and Project Grants[63]

Table 3: Overview of NHMRC's restructured grant program[64]

| Grant type |

Investigator Grants |

Synergy Grants |

Ideas Grants |

Strategic and Leveraging Grants |

| Purpose |

To support the research programs of

outstanding investigators at all career stages |

To support outstanding

multidisciplinary teams of investigators to work together to answer major

questions that cannot be answered by a single investigator. |

To support focussed innovative

research projects addressing a specific question |

To support research that addresses

identified national needs |

| Duration |

5 years |

5 years |

Up to 5 years |

Varies with scheme |

| Number of

Chief Investigators |

1 |

4-10 |

1-10 |

Dependent on

individual scheme |

| Funding |

Research support package (RSP) plus

optional salary support |

Grant of a set budget ($5 million) |

Based on the requested budget for

research support |

Dependent on individual scheme |

| Maximum number of applications allowed

per round* |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Not capped relative to Investigator,

Synergy and Ideas Grants. Dependent on individual scheme. |

| Maximum number of each grant type that

can be held** |

1 |

1 |

Up to 2** |

Not capped relative to Investigator,

Synergy and Ideas Grants. Dependent on individual scheme. |

| Indicative MREA allocation |

About 40% |

About 5% |

About 25% |

About 30% |

**

A maximum of two grants can be held concurrently, by any individual, with the

following exceptions and conditions: (1) individuals who hold two Ideas Grants

can hold concurrently a Synergy Grant, (2) individuals who hold up to two Ideas

Grants can apply for, and hold an Investigator Grant, but their RSP will be

discounted until the Ideas Grant/s have ended and (3) individuals may apply for

an Investigator Grant concurrently with an Ideas Grant, and if both

applications are successful only the Investigator Grant will be awarded.

2.46

In speaking specifically to the Ideas Grants, Professor Kelso informed

the committee that this scheme replaces some of what the Projects Grants scheme

achieved, 'but in a more effective way'.[65]

Professor Kelso continued:

The purpose of this scheme is to focus on research which is

highly innovative, creative and does not require that somebody has a long track

record of research, which is an impediment for many people getting started,

attempting to change fields or addressing an important new question. Of course,

it's still going to be highly competitive, it's going to be highly rigorous but

it will have a different flavour from the current Project Grants scheme, which

has become increasingly competitive, such that people's track records have

become a very important driver in that scheme. So I'm very optimistic that the

Ideas Grants scheme is going to fill an important gap in our current range of

schemes.[66]

2.47

Dr David Whiteman of the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute

welcomed that the Ideas Grants were 'less focussed on track record and more

focussed on innovation', and acknowledged that while it is not a large pool of

money, 'it is a pool of money to address the issue of innovation and ensure

that innovative cutting‑edge ideas from younger early-career investigators

get picked up'.[67]

2.48

In speaking to the new five year grants for research, Professor Linda Richards

considered this a significant improvement compared to the previous three-year

funding structure, noting that this:

...is a huge step forward for everybody in terms of the amount

of time writing grants and the amount of time reviewing grants and also the

amount of time it takes to do high-quality research. You cannot do this in a

three-year funding cycle. It is just too short, especially for an organ system

like the brain, because the work is slow and time-consuming and it takes time

to do quality research. One thing though is that the NHMRC does have a fourth

category, which is for targeted research, and I would implore you that brain

research, in particular brain cancer, is one of those areas that we should be

targeting in this country.[68]

2.49

Dr Jens Bunt elaborated:

It is really hard to get long research programs, because most

of the project grants are for three years. Sometimes setting up something

ambitious or that is more risky takes more time. For instance, even though we

did not have funding for it, we invested three years to develop a mouse model.

It took us three years to get the exact model to mimic certain cancer

development. It is really hard to get funding for those kinds of things and

sometimes you have to think far ahead and invest a lot in developing techniques

and novel ideas that do not really directly fit in a project realm. There is

always an assumption of a small group of people working on something that is

finished within a certain set time. Whereas we, especially with rare cancers,

because we do not know that much yet, need to really develop these things with

multiple people from multiple different disciplines to work on it. It is really

hard to get sufficient scientific funding for that. I think this would also

help. But at the moment we have to think in packages of three years, which

makes it harder.[69]

2.50

Ms Emma Raymond also informed the committee that Wesley Medical Research

had to cease collecting samples, identifying the lack of longevity of funding

as a problem:

The problem is that people give you the money to set

something up and give you the infrastructure and the equipment, but there is no

longevity, so there is no funding to continue what we are doing. I have seen a

lot of biobanks go out of business when they have lost their funding from the

NHMRC. The problem is that we have a duty of care to these patients. We have

collected their samples to help other patients. If we lose our funding, then we

have to basically shut the doors, which is what happened at [the University of

Queensland] with their brain bank.[70]

2.51

Research Australia, which postulated that the changes to the NHMRC

funding structure 'are positive for the subject of this inquiry',[71]

also spoke to the importance of secure long term funding for research. Research

Australia stated that in order to see the greatest outcomes, research must be

funded for an extended period of time, as '[r]esearch, by its nature, is a long

term prospect', and provided the following example:

...to develop a new drug, from the initial stages through to

the end, takes anywhere between 10 and 15 years and can cost up around $3 billion.

So these are very intensive processes that need support over a long period.[72]

2.52

Although the overall changes to the grant program have been welcomed by

some, Dr Elizabeth Johnson of the VCCC warned that the NHMRC's 'capacity to

support multidisciplinary research may have been reduced' by these changes,

explaining that:

The focus is shifting away a little bit from the old

fashioned program grants, where you got a number of multidisciplinary teams, a number

of different people who had come from different institutions, who worked

together to support a particular research initiative. They typically tended to

be a bit bigger. We have yet to see how the restructure plays out, but the

NHMRC funding structure might not now be the ideal support for the type of

multidisciplinary approach that we need to really tackle [survival rates]

properly.[73]

Cancer Australia

2.53

Cancer Australia, a statutory body established in 2006 pursuant to the Cancer

Australia Act 2006, is 'the lead national cancer control agency' and 'aims

to reduce the impact of cancer, address disparities and improve outcomes for

people affected by cancer by leading and coordinating national, evidence-based

interventions across the continuum of care'.[74]

2.54

Cancer Australia has the following functions:

- to provide national leadership in cancer control;

- to guide scientific improvements to cancer prevention,

treatment and care;

- to coordinate and liaise between the wide range of groups

and health care providers with an interest in cancer;

- to make recommendations to the Commonwealth Government

about cancer policy and priorities;

- to oversee a dedicated budget for research into cancer;

- to assist with the implementation of Commonwealth

Government policies and programs in cancer control;

- to provide financial assistance, out of money

appropriated by the Parliament, for research mentioned in paragraph (e) and for

the implementation of policies and programs mentioned in paragraph (f);

- any functions that the Minister, by writing, directs

Cancer Australia to perform.[75]

2.55

In its submission, Cancer Australia noted that it performs its function

to oversee a dedicated budget for research into cancer[76]

through administration of the Priority-driven Collaborative Cancer Research

Scheme (PdCCRS).

2.56

The PdCCRS, established in 2007, 'brings together government and other

funders of cancer research to coordinate, co-fund and maximise the number of

cancer research grants funded in Australia',[77]

and was established:

...in order to:

-

better coordinate funding of

priority-driven cancer research;

-

foster collaborative cancer

research and build Australia’s cancer research capacity, and

-

foster consumer participation in

cancer research, from design to implementation.[78]

2.57

In determining which research programs to fund, Cancer Australia uses

'an evidence based approach' to fill gaps in funding, which was described to

the committee by Dr Paul Jackson:

We look at the national pattern of funding to cancer

research, which includes the funding that is provided from both national and

international sources, and, using that profile, we examine the funding that

goes to different tumour types as well as the funding across the broad areas of

the research spectrum—the main areas of the funding to where that project goes.

We then use that evidence to identify opportunities for us to make strategic

investments where there are gaps or opportunities to further research. That,

for example, can be in tumours which may be of high burden and poor survival,

where there are opportunities to strategically invest to address that.[79]

2.58

Dr Jackson informed the committee that in determining which applications

to fund, a merits-based approach is used, such that Cancer Australia funds:

...from the top-ranked merit based application downwards. We

maximise the amount of funding, or the number of grants that we're able to

fund, through collaborative funding with our funding partners in the scheme. We

start from the top down. Once the funding has ended, that's where we have to

stop funding.[80]

2.59

Dr Whiteman commended Cancer Australia on this approach:

I think the activities that Cancer Australia has done in just

looking back and saying: 'What have we funded previously? Does that reflect

where we want to invest our funding?' are very helpful, because they then put

the spotlight on neglected areas of research, including low-survival cancers. I

think there is a mood for recognising where there are deficits in funding, and

then looking for mechanisms to correct that.[81]

2.60

Other witnesses described the type of funding they receive from

Cancer Australia, and the positive impact this has had on their research.[82]

For example, Ms Delaine Smith of the ALLG informed the committee that:

...the ALLG, and now 13 other cancer trial groups around

Australia, have been able to have funding come straight from Cancer Australia.

That is about half a million dollars a year. The infrastructure that it

supports is very specific because Cancer Australia is very specific about how

it can be spent. So it goes towards the activities that develop clinical

trials. For us, in the ALLG, we utilise that funding on EFT and on roles and

positions that help prepare the clinical trial protocol. The protocol is the

instruction document that is going to go to the hospital to tell them what to

do in a very methodical and meticulous way. You cannot understate the

importance of preparation. Preparation is key.[83]

2.61

However, the committee also heard that Cancer Australia could have a

lead role with respect to 'developing, implementing and maintaining' a

sustained focus on LSR cancers.[84]

Further discussion about a national strategy for LSR cancers appears at chapter

5.

The Medical Research Future Fund

2.62

The MRFF, which operates pursuant to the Medical Research Future Fund

Act 2015 (MRFF Act), was established as part of the 2014–15 Federal Budget

with the purpose of providing:

...a sustainable source of funding for vital medical research

over the medium to longer term. Through the MRFF, the Government will deliver a

major additional injection of funds into the health and medical research sector.[85]

2.63

The $20 billion fund 'offers the opportunity to strategically fund

research and address national priorities in a cohesive and coordinated way'.[86]

The MRFF 'complements existing medical research and innovation funding', such

as the NHMRC, the Commonwealth Science Council and the National Innovation and

Science Agenda, 'to improve health outcomes by distributing new funding in more

diverse ways to support stronger partnerships between researchers, healthcare

professionals, governments and the community'.[87]

2.64

The operation of the MRFF is summarised in the MRFF Act as follows:

The Medical Research Future Fund consists of the Medical

Research Future Fund Special Account and the investments of the Medical

Research Future Fund. Initially, the Fund’s investments are a portion of the

investments of the Health and Hospitals Fund which was established under theNation—building Funds

Act 2008. Additional amounts may also be credited to the Medical Research

Future Fund Special Account.

The Medical Research Future Fund Special Account can be

debited for 3 main purposes:

- channelling grants to the COAG Reform Fund to make grants

of financial assistance to States and Territories; and

- channelling grants to the MRFF Health Special Account to

make grants of financial assistance to certain bodies; and

- making grants of financial assistance directly to

corporate Commonwealth entities.

The Australian Medical Research Advisory Board is established

to determine the Australian Medical Research and Innovation Strategy and the

Australian Medical Research and Innovation Priorities. The Health Minister takes

the Priorities into account in making decisions about the financial assistance

that is provided from the Medical Research Future Fund Special Account.

There is a limit on the amount that can be debited from the

Medical Research Future Fund Special Account each financial year. The limit,

which is called the maximum annual distribution, is determined by the Future

Fund Board for each financial year.

The Medical Research Future Fund is invested by the Future

Fund Board in accordance with an Investment Mandate given by the responsible

Ministers.[88]

2.65

Professor Ian Frazer, Chair of the Australian Medical Research Advisory

Board (AMRAB) which determines the Australian Medical Research and Innovation

Strategy and the Australian Medical Research and Innovation Priorities pursuant

to the MRFF Act,[89]

outlined for the committee the differences between the NHMRC and the MRFF:

The National Health and Medical Research Council largely

gives funding out in reply to specific proposals from individual researchers.

It does have some priority areas which it uses, but the vast majority of

funding is in response to a particular proposal on a particular bit of research

determined by the investigator themselves. The Australian Medical Research

Advisory Board advisory to the Medical Research Future Fund rather takes the

view of top-down driven research where we have recommended to the minister

priorities where we believe that research money should be best spent.

Therefore, while there might be a call for proposals in due course, at the

moment the money is being dispersed on the basis of the priorities and

strategies that we set when we completed our consultation with the medical

research community, the general public and other interested parties in the

course of 2016.[90]

2.66

Professor Frazer considered that the MRFF Act provides sufficient

flexibility in the granting of funding, specifically in relation to

collaboration across institutions:

Certainly, the funding will have to be administered by one

individual organisation which is responsible for its acquittal back to

government. But the concept of collaboration in research is pretty much

international, of course. Certainly, there is nothing intended about the way

that we made the strategy of priorities to suggest that we did not wish to see collaboration.

In fact, we positively expected that there would be collaboration and pointed

out that the value of collaboration, for example, between different research

institutes in this country and overseas, and research institutes and industry,

should be positively encouraged.[91]

The 2016–2021 strategy

2.67

Following consultation with the sector and the broader community, and

pursuant to the MRFF Act,[92]

the AMRAB developed six strategic platforms to underpin the Australian

Medical Research and Innovation Strategy 2016–2021 (the Strategy) that 'capture

and group together themes and provide a framework for the [Australian

Medical Research and Innovation Priorities 2016–2018] to improve research

capacity and capabilities in the research sector'.[93]

A list of priorities falls under each of these strategic platforms.[94]

2.68

The Strategy also sets out how the MRFF aligns with and compliments the

NHMRC, the National Science and Innovation Agenda, and other interests, such as

state and territory governments and the private and not-for-profit sectors;[95]

as well as the challenges facing the health and medical research sector.[96]

2.69

The strategic platforms of the Strategy are:

-

strategic and international horizons: funding to support

Australian participation and leadership in 'international research projects

focusing on major global health challenges and threats...complimentary to the

international collaborative activities of the NHMRC';[97]

-

data and infrastructure: funding for research that 'enables

the planning and implementation' of 'an integrated national health data

framework that supports healthcare delivery, service improvement and best

practice adoption';[98]

-

health services and systems: in contrast to the current

product and drug focussed medical research and the domination of the acute care

experience for research on health interventions, the intention is to bolster 'Australia’s

capacity in health services and systems research' by, for example, 'investment

activities...with the Medicare Benefits Schedule Review Taskforce and new policy

and program agendas, such as the Australian Government’s Health Care Homes

trial';[99]

-

capacity and collaboration: the focus is research

collaboration, to be achieved by 'investing in multi-disciplinary, institute

and sector teams', which could extend to collaborative funding, 'by leveraging

co-investment from other governments, private and philanthropic interests';[100]

-

trials and translation: the facilitation of 'non-commercial

clinical trials of potential significance', including by supporting

NHMRC-accredited Advanced Health Research and Translation Centres;[101]

and

-

commercialisation: supporting 'the creation and brokering

of linkages between researchers and industry that are transdisciplinary in

nature', noting the need for '[a] two-way exchange of knowledge and expertise

in research, and its translation into clinical practice' and better

encouragement 'adoption of the requirements for successful commercialisation in

both the academic and business environment'.[102]

2.70

Professor Frazer commented that, for the next round of consultations,

improvements could be made to AMRAB's processes:

...we may actually have to get focus groups together and

specifically engage, through the recruitment of individuals who would not

otherwise necessarily come forward, to get a more general representation of

what the public is interested in. One of the practical realities, of course, is

that people become most interested in the health system when they actually need

to use it, and yet the vast majority of people out there who might, in the

future, benefit from it, do not actually use it at the moment.[103]

2.71

Indeed, Professor Rosalie Viney of the Australian Health Economics

Society advocated for an additional injection of funds from the MRFF into

health research 'across the board':

It shouldn't just be in the discovery science; it needs to be

across the whole of translation. But I think it's absolutely critical that that

is done in a way that maintains the standards of excellence in research,

maintains the standards of scientific quality, makes sure that we apply the

same well-established principles that organisations like NHMRC have had for

peer review and for quality, and that that continues.[104]

2.72

However, Dr Richard De Abreu Lourenco warned that if the MRFF were to be

used for discovery research, it could be viewed 'as an implication of support

for commercialisation' from the government.[105]

First disbursements

2.73

The first disbursements of the MRFF, implemented in 2016–17, invested

$65.9 million:

-

$20 million for preventive health and research translation

projects.

-

$33 million for clinical trials that will build on Australia’s

world class research strengths and ensure Australia is a preferred destination

for research.

-

$12.9 million for breakthrough research investments that drive

cutting edge science and accelerate research into better and new treatments and

cures.[106]

2.74

Professor Terrance Johns of the Brain Cancer Discovery Collaborative,

who stated that his institution 'is not a large institution with political

clout', noted that '[t]here was no call for grants for MRFF funding' for its

first disbursements, and observed that the funds are 'pretty much locked up by

the G8 universities'.[107]

Professor Johns opined that, at present, the MRFF 'is about political

clout'.[108]

2.75

However, Mr Peter Orchard, whose organisation CanTeen Australia was a

recipient of some MRFF funding, suggested that '[t]o some extent, the MRFF is

in its absolute infancy, and so being able to comment on it feels difficult at

this stage, other than to say I am very grateful for it'.[109]

2.76

Indeed, Mr Mullins of Research Australia spoke to the benefits of the

MRFF:

...the MRFF funding, with its emphasis on translation, offers

new opportunity for advances that will benefit patients. The MRFF, importantly,

also has a top-down approach to funding. It is driven by a five-year strategy

and priorities, and the latter must explicitly take into account the burden of

disease, how to deliver practical benefits to the Australian community and

value for money. This must be combined with a focus on funding excellent

research, obviously, if it is to be successful, but it provides greater scope

for strategically directing funding to particular areas.[110]

Philanthropic funding

2.77

As indicated at paragraphs 2.32–2.33 above, philanthropic funding can be

vital to advances for research into LSR cancers, especially when researchers

find it difficult to obtain government funding.

2.78

Indeed, it was noted by the ANZCHOG National Patient and Carer Advisory

Group that 'oncology units are often largely dependent upon philanthropic and charitable

donations' to meet costs associated with enrolment in and compliance with

international trials, emphasising that '[c]urrently paediatric centres rely

heavily on philanthropy, charities and individual hospital budgets to fund most

cancer clinical trials'.[111]

2.79

To illustrate what such funding can achieve, the Mark Hughes Foundation

(MHF) outlined that in three years, it has contributed to the following

improvements in respect of brain cancer:

-

A Brain Cancer Biobank at [the Hunter

Medical Research Institute]

-

Over $300,000 in project grant

funding and various Travel Grants to allow brain cancer researchers attend

international conferences to present their work and establish important

research collaborations

-

A clinical research fellowship in

Brain Cancer

-

A dedicated Brain Cancer Care

Nurse at John Hunter Hospital

-

Communal brain cancer research

register with Brain Cancer Biobanking Australia[112]

2.80

Further, Professor Mark Rosenthal of the VCCC spoke to the work of the Cure

Brain Cancer Foundation (CBCF), a philanthropic organisation focused

exclusively on brain cancer, in providing financial assistance for brain cancer

research:

The [CBCF] has done terrifically well through, really, one

individual driving that over many years, but they now have a very established

philanthropic organisation that runs professionally and relatively

independently. We have made sure that there is rigour to their grant

application process and the grants that have been given out. It is not in

competition with NHMRC. It has grown because of the need for it. It would be

great if we did not have to have philanthropic funding, but actually we are

lucky in brain that at least there is some. We have only had one round of

grants, which total up to $2 million, I think.[113]

2.81

However, Associate Professor Gavin Wright identified a significant issue

with attracting philanthropic funding for LSR cancers, namely, the lack of

survivors:

The trouble with the philanthropic side of things is often

you need survivors, who generate a lot of push for these sorts of things. They

go to companies. The catch 22 is that, if you have a poor-survival cancer, you

do not have many survivors. If it is affecting a lower socioeconomic group, you

do not have the movers and shakers.[114]

2.82

Furthermore, as Dr Johnson noted, 'success breeds success' in terms of

the growth of philanthropic cancer support groups, observing that:

Once you have a critical mass of funding you can then do more

with it—you can advertise more and you can grow your foundations more. There

are numerous lesser-known small cancer foundations which really do exist on the

smell of an oily rag.[115]

2.83

The committee therefore heard calls for various improvements in respect

of philanthropic funding. For example, in addition to the recommendation by

Research Australia at paragraph 2.35 above that the government fund indirect

costs of research in order to 'allow more philanthropic funding to be directed

to support novel early stage research and early career researchers',[116]

Professor Guy Eslick called for greater philanthropy from 'wealthy

Australian businesses and individuals'.[117]

2.84

In his submission, Professor Eslick drew a contrast between the philanthropic

funding Harvard University received for research during his post-doctoral

training at Harvard ($100 million), compared to that received by the University

of Sydney in that same week ($10 million).[118]

Professor Eslick suggested that the government could encourage philanthropists

to donate to universities and research institutions by offering greater

incentives.[119]

2.85

The committee also received the following suggestions for improvement

with respect of philanthropic funding:

-

the Lung Foundation Australia called for the '[p]hilanthropic

community to establish specific targets for donations to lung cancer research';[120]

-

the MHF called for '[t]argeted Federal and state funding towards

brain tumour research, leveraged with funds from philanthropic agencies' to enhance

productivity in the field of brain cancer research;[121]

and

-

Ovarian Cancer Australia recommended the development of 'a

national strategy for coordinating the planning and funding of cancer research

across the government, medical, health, research and philanthropic

communities'.[122]

2.86

Despite the evidence from a number of submitters about their difficulty

in securing philanthropic funding, Mr Todd Harper of the Cancer Council

Victoria informed the committee that his organisation had not found it

difficult to get philanthropic support for research into LSR cancers, asserting

that:

...we have found that there is both an appetite amongst

philanthropy to invest in the haematology of less common cancers and in the

high-risk, high-return research. I think what is critical here though is that

one of the things that makes it more likely that philanthropy would fund these

is if they can have assurances over the quality or the rigour of the scientific

processes that assess those proposals. I think there is opportunity to bring

together the best scientific minds to assess high-quality proposals that can be

funded by philanthropic organisations like ours, or indeed others. I think

government can also play a role in providing seeding or cooperative funding to

enhance the chances of those programs being successful and the chances of those

programs being successfully funded.[123]

2.87

However, the committee also heard that '[p]hilanthropy will only go so

far': in speaking of the establishment of a centre for research excellence, although

the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research had benefitted from

philanthropic funding when NHMRC funding was not available, Professor Clare Scott

noted that '[g]overnment funding would allow us to entrench these approaches in

Australian medicine'. [124]

Pharmaceutical funding

2.88

A number of witnesses, whose clinical trial research was funded by

pharmaceutical companies, outlined for the committee the importance of funding

from pharmaceutical companies for cancer research.[125]

However, as the below evidence demonstrates, many witnesses were also critical

of the reluctance of pharmaceutical companies to become involved in drug

development for people with LSR cancers.

2.89

Roche Products Pty Limited (Roche), a research‑based healthcare

company focussing on pharmaceuticals and diagnostics, discussed the role of

pharmaceutical companies in improving survival rates for LSR cancers:

The pharmaceutical industry is a critical component of the

innovation ecosystem. Not only does industry contribute to basic research and

takes the lead in taking medicines through regulatory and reimbursement

processes, it is also the leading funder of clinical trials.[126]

2.90

Roche identified that improving survival outcomes for people with LSR

cancers is dependent on a number of factors including overcoming barriers to

participation in clinical trials (by clinicians as well as patients), and

affordable access to treatments through the PBS.[127]

Roche identified that '[b]reakthroughs in personalised medicine and

immunotherapy are offering hope to patients with both common and rare cancers –

yet these products face many challenges in navigating the reimbursement

system'.[128]

2.91

Indeed, a recent Deloitte Access Economics (Deloitte) report noted that

currently, 'only a small proportion of the potential indications for which

immunotherapies are able to be used in cancer treatment receive subsidised

funding from the Government', and as these therapies are expensive to develop

and produce, treatments 'are prohibitively expensive for many patients who seek

to self-fund'.[129]

A further discussion of this report, and its recommendations, appears at

chapter 5.

2.92

Medicines Australia—'the Australian peak body for the discovery-driven

pharmaceutical industry'—identified other challenges for pharmaceutical

companies particularly in respect of the policy and access environment:

The broader policy environment is also challenging the

investment decisions made by pharmaceutical companies. Increasing levels of uncertainty

caused by a single payer system, as well as inconsistent approaches to

intellectual property, aggressive pricing policies and an unpredictable policy

environment, are among the issues which Medicines Australia finds to be of some

concern.[130]

2.93

The committee also received evidence that there is a limited incentive

for pharmaceutical companies to fund clinical trials for LSR cancers,[131]

with one witness describing the lack of funding for brain tumour research 'very

disappointing'.[132]

Other barriers to clinical trials distinct from pharmaceutical funding that are

faced by people with LSR cancers is examined in chapter 3.

2.94

Speaking to the involvement of pharmaceutical companies in drug

development, Professor Richards asserted that 'it is unethical not to think about

those patients [with LSR cancers] and not to be trying to develop treatments

for them', arguing that '[t]hat is where government has to step in'.[133]

Professor Richards stated that:

...pharmaceutical companies have been turning away from drug

development for brain, partly because we, firstly, did not know enough about

the pathways involved to make the clinical trials effective. Also, for rare

diseases, of course, the market is not there for the company to want to invest

in a drug that is going to be used by a small number of patients.[134]

2.95

The ANZCHOG National Patient and Carer Advisory Group also recognised

the importance of return on investment for pharmaceutical companies, submitting

that '[t]here is little economic incentive for pharmaceutical companies to fund

paediatric cancer trials' as childhood cancers are 'made up of rare and

ultra-rare diseases'.[135]

2.96

This was also reflected by Mrs Therese Townsend, a pathology scientist who

has a neuro-endocrine tumour:

The costs of running such trials are disproportionate to the

potential profit when there are few potential “customers”. When those who may

benefit have inherently poor prognoses, courses of treatment are likely to be

short, and this further minimises the return on research investment. Hence there

is no financial incentive for private enterprise to conduct such trials,

especially in Australia due to its decentralisation and small population base.[136]

2.97

Dr Chris Fraser spoke to two barriers to participating in international

clinical trials: first is the cost of participation, and second, the increasing

requirement to partner with pharmaceutical companies.[137]

Dr Fraser elaborated on this second barrier:

Historically, this was very much an academic pursuit and

there were not new drugs, as I outlined, so we were able to do this amongst

ourselves. As these new drugs are developed, we increasingly have to partner

with pharma companies. Australia is not a big market. It is expensive for them

to open these trials in Australia. There may be only one, two or three

Australian patients that are eligible for a particular trial. So we need to

work out a structure that means we can still participate in these trials. The

first step to that is to make sure that we have a very robust clinical trials

infrastructure so that we are up and ready to start these trials so the

pharmaceutical companies know that the infrastructure and the organisations are

there to make sure that the process will run smoothly.[138]

2.98

Indeed, the Garvan Institute of Medical Research/The Kinghorn Cancer

Centre/The Garvan Research Foundation (Garvan Institute) identified that '[t]he

cost of drug development, which must be recouped by the pharmaceutical

industry, already limits access of some patients to important treatment

options' and outlined the significant cost of running trials:

The financial costs of conducting clinical trials have

doubled every nine years for the past 50 years. The estimated combined costs

per patient in a cancer clinical trial rose from less than US$10,000 to around

US$47,000 between 1980 and 2011. The average phase 2 study of 40 patients costs

upwards of US$2-10M, while the average phase 3 study costs upwards of US$40M.

Average development costs are estimated at around US$3.6 billion dollars per

drug.[139]

2.99

However, the Garvan Institute also informed the committee about the

alternative ways it has engaged with pharmaceutical companies to conduct

clinical trials. In order to minimise the barriers to engagement with

pharmaceutical partners in respect of its Molecular Screening and Therapeutics

(MoST) study, the Garvan Institute sought only:

...access to study drugs for each module and for engagement

with the pharmaceutical partner in data interpretation, as well as

decision-making regarding expansion of a drug–disease cohort in which a significant

signal of activity has been identified.[140]

2.100

Professor David Thomas of the Garvan Institute explained how this system

works in practice:

...we invest in drugs by where they are arise. If you invest in

breast cancer, you authorise and reimburse drugs on the basis that it works in

breast cancer, and that drives the way in which pharma invest. The problem is

that many of these drugs work across a whole range of cancers, because a whole

range of cancers have this particular common molecular abnormality. A molecular

taxonomy is required. That requires molecular screening. Pharma cannot invest

in screening 10,000 people to find 20 to treat, but we can. If we can match our

research investment with the opportunities from pharma, so we can create a

healthy model of collaboration with the benefit of pharma in mind but also

getting patients onto trials, that is a virtuous cycle.[141]

2.101

Further discussion about clinical trials appears at chapter 3, and

further discussion about the treatment of cancer through personalised medicine

and immunotherapies is found in chapter 5.