Chapter 8 - Inpatient and crisis services

One thing I came to understand clearly over these years of

dealing with and talking to the crisis teams and the staff of the mental health

centres is that the system is so under-resourced that they must deal with the

life and death cases first and other cases necessarily come second. This is a

brutal reality which should not exist in a civilised society.[747]

8.1

Mental health inpatient and crisis services are under

significant strain. Witnesses to the inquiry despaired at the absence of

treatment or other interventions in all but the most immediate life-threatening

situations. There was a clear call for increased resources to meet current

needs, to improve service availability and standards of care.

8.2

The committee received many harrowing personal stories

from consumers, carers and others about inpatient treatment experiences and

mental health crisis situations, in some instances leading to tragic deaths.

Many expressed their frustration and anger. Others expressed despair. Some

submitters had seldom told their stories before, feeling alienated and

stigmatised because of their circumstances. The committee appreciates the great

effort and courage they showed in giving evidence to this inquiry.

8.3

Other contributors had told their stories before, many

times. They commented that the same issues have been presented over and again

in different forums.[748] The committee

appreciates the determination these submitters show by continuing to contribute

their experience, knowledge and ideas to help improve mental health services

and ultimately the lives of those experiencing mental health problems.

Mental health care in an age of deinstitutionalisation

8.4

Care for people experiencing severe mental illness has

undergone a revolutionary transformation over the last few decades. Australia

had around 30,000 acute care psychiatric beds in the 1960s. The number of

public beds had fallen to around 8,000 at the time of the development of the

National Mental Health Strategy (NMHS), and is

now around 6,000.[749] This decline was

driven by several factors[750]:

-

Changes in views about human rights, treatment

and care for people experiencing mental illness

-

Improvements in treatment for mental illness,

particularly through new pharmaceuticals

-

Effective antibiotic treatment of syphilis,

avoiding the need for psychiatric hospitalisation in advanced cases of the

disease

-

Evolution of specialised aged care facilities

that could manage geriatric illnesses, particularly dementia

-

Creation of specialised institutions for people

with intellectual disabilities, and

-

Audits and reviews of stand-alone psychiatric

institutions that were highly critical of the care they provided.[751]

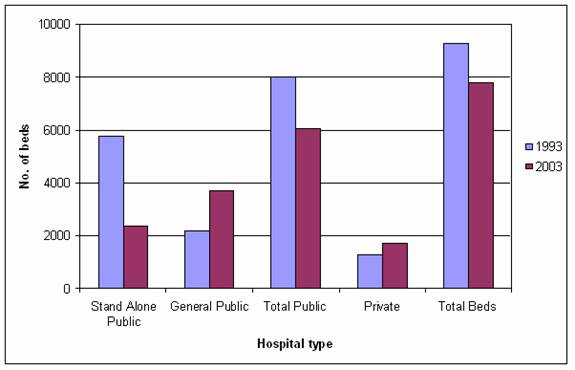

8.5

The closure of stand-alone psychiatric institutions is

often referred to as deinstitutionalisation.[752]

Figure 1 shows the change in beds over the last decade, and demonstrates two

key trends: the shift in beds from stand-alone facilities to general hospitals;

and the decline in the total number of beds, as more care takes place in the

community.

Figure 1: Number

of psychiatric hospital beds[753]

8.6

While deinstitutionalisation has meant closure of many

stand-alone psychiatric institutions, this closure has not happened in

isolation. It was meant to operate hand-in-hand with two parallel developments:

mainstreaming, involving the location

of acute psychiatric care facilities at general hospital sites; and the expansion of community care, ensuring

that people no longer in institutions have adequate care in their communities.

8.7

However, there is a general sense that mainstreaming

and community care have not kept up with the pace of deinstitutionalisation.

There are widespread problems with adequate accommodation, quality of care in

the new settings, and perhaps most clearly of all, problems for people in

gaining access to care in the new environment.[754] In this environment, it is not

surprising that the current policy direction is sometimes called into question.

The strong consensus that continues to exist around deinstitutionalisation may

be threatened if the policy is not fully and properly implemented and

community-based services significantly expanded. Much of the disenchantment

with the current system crystallises around experiences of acute care, but as

this report shows, the answer lies in improvements in every level of care and a

great deal more emphasis on community-based services than is currently the

case.

8.8

This chapter sets out the issues in relation to the

care people seek when acutely ill. People experiencing acute mental illness now

usually seek access to one of three types of service: hospital inpatient

services; emergency departments; or crisis assessment teams.

Inpatient services

Pressure on acute care places

8.9

Witnesses reported that unless a person experiencing

mental illness is considered to be a threat of immediate harm to themself or

others, there is little chance of their being admitted to hospital.[755] Some of the most devastating

evidence presented to the committee told the stories of those who knew they had

become unwell, had tried to seek hospital admission, been denied and

subsequently sought to harm themselves or others.

There were many instances of death or injury that were easily

attributed to not being admitted. A patient in Nepean

Hospital was placed on leave, while

trying to settle over the weekend, and on returning to the hospital unsettled,

to his promised bed found it had been filled. He went home and killed himself

and others in the family.[756]

One parent for example rang in saying her son had gone three

times to the local community mental health service and was repeatedly sent

away. The parents took him once and the Doctor on duty asked him if he was

going to kill himself. When he answered no the doctor said there was nothing

wrong with him and sent him away. He then drove his car through the hospital

front doors and was subsequently admitted for three days.[757]

8.10

A number of state government submissions to the inquiry

acknowledged the pressure on inpatient mental health services. The Victorian

Government stated:

In Victoria,

the current operating environment is one of sustained demand pressure. There

are a number of inter-related issues that place pressure on the mental health

system including growing demand, and increases in complex and involuntary

clients. Their impact is most evident in two key aspects of the hospital

system: adult acute beds and hospital emergency departments.

Client growth of more than 7 per cent per annum over five years

has led to services operating over capacity, as evidenced by high community

caseloads and chronic acute bed blockages, with 9.6 per cent of patients

staying more than 35 days. This has resulted in crisis driven services

responses, difficulties with service and bed access, 'revolving door' clients

(15 per cent each year) and a significant impact on other social policy areas.[758]

8.11

In New South Wales:

The level of psychiatric distress and disability in the

community is rising. Reasons for this change are poorly understood but may

include broad social changes, changes in social supports and social capital,

increasing inequality, and changes in patterns of drug use. Available resources

have not kept up with increased demand. Across Australia

there are problems with access to acute care, continuity of care and the availability

of coordinated and comprehensive community support. A time lag exists between

recognition of increased demand and construction and commissioning of new units

and the development and implementation of community based programs.[759]

8.12

This analysis is supported by other reviews of mental

health services, such as the Not for Service

report,[760] the South Australian

Legislative Council inquiry,[761] and

the Western Australian Legislative Council inquiry.[762]

The impact of acute bed shortages

8.13

Denying admission can result in ongoing hardship for

consumers and their carers. Consumers have in some cases been abandoned to a

cycle of homelessness and abuse. The costs of not providing treatment and care

when sought, both in terms of quality of life and later need for services, is

significant.

8.14

Early discharge from hospital places a significant strain

on families, which in turn creates a need for services:

Discharge from hospital is frequently too soon because of the

pressure for beds and carers assume responsibility for the consumer in a state

of unwellness. Programs are needed to provide support, information and skills

development to enable carers to cope in this kind of situation.[763]

8.15

Individual submissions from carers demonstrated

ARAFMI's concern:

Severe shortage of hospital beds...results in clients not being

admitted to hospital when there is a real need, or being sent home too soon,

with no other options. I have been called on the day my son is to be

discharged, and without prior warning, been told that I am to come and collect

him. When I have show reservations because I felt that he was not well enough,

and that I couldn't ensure his safety, I have been given the only other option

of having him sent to a homeless men's shelter...[764]

8.16

Carers illustrated the significant cost incurred when

patients 'recycle' through the hospital system:

After being put into hospital, my daughter with schizophrenia

was given medication for a few weeks and released, despite the family all

pleading with the hospital to keep her a bit longer as it was quite clear to us

this medication was not reducing her psychosis. In fact she had to be taken

back to the hospital within a week. She was put on another medication and

stayed in hospital a while. Then, again, despite still having intense psychotic

episodes she was let out – despite our huge concern. Off the record hospital staff

told me the reason she was let out was due to a shortage of beds! She had to be

re-admitted for the third time around August.[765]

My son was increasingly unwell for three months. When I asked

for help because of the case workers heavy work load they said he wasn't ill

enough.

At the end of the three months he was hospitalized six times in

two months.

He was discharged TOO early everytime because there were 25 beds

for up to 600 patients. He suffered unnecessarily and stress on the family was

enormous.[766]

The causes of acute bed shortages

8.17

The lack of acute beds has several interrelated causes.

While insufficient bed numbers was one factor raised, inadequate

community-based facilities appeared to be the central issue. Without

intervention programs and accessible community treatment, assistance and

support, the symptoms of mental illness can escalate, leading to acute episodes

and increased demand for inpatient services.

8.18

Following episodes of inpatient care, a lack of 'step

down' rehabilitation services and community supports can make discharge

difficult, resulting in longer inpatient stays than necessary. Consequently,

patients whose needs could be catered for in a less restrictive community

environment are retained in hospital, 'blocking' bed availability for new patients.

In other cases a combination of insufficient inpatient beds and inadequate

community facilities means that patients are discharged too early into

inadequate circumstances.

8.19

The NSW Nurses' Association reported that premature

discharge was the most common response to pressure for acute beds. A survey of

their members in 2004 found that:

Prematurely discharging patients was the number one way of

dealing with the problem, with 29 per cent indicating this method. Next highest

scoring method was keeping them in emergency departments (23 per cent) or

general wards (6 per cent), refrain from admitting them (13 per cent), manage

them in the community (11 per cent), or transfer them around the state (8 per

cent). About 8 per cent also indicated they routinely had mental health

patients sleeping on couches or on mattresses on the floor.[767]

8.20

Dr Morris,

Executive Director of the Gold Coast Institute of Mental Health, expressed the

view that state mental health acts were being misapplied in order to deny

admissions, due to the shortage of acute psychiatric beds.[768]

8.21

Several states acknowledged that some admitted patients

could be better served within the community, if adequate supports existed. In Queensland:

A recent snapshot of mental health inpatient beds conducted in December

2004 indicated that 30 percent of patients did not need hospitalisation if

other options were available. Similar pictures occurred across most

jurisdictions which participated in the exercise. Difficulty in accessing

suitable support and accommodation was the key factor preventing discharge.

This represents substantial numbers of patients accommodated in inpatient care,

effectively blocking throughput and being accommodated, often at acute bed day

costs, placing further pressure on systems already operating at maximum level

and with finite resources.[769]

8.22

In South Australia:

The Homeless and Housing Taskforce of the Australian Health

Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) draft report titled Australian Mental

Health Inpatient Snapshot Survey 2004 indicates that there were 505 patients in

10 mental health inpatient units on Census day in SA for whom immediate

discharge would have been possible if more intermediate treatment, rehabilitation

support and accommodation services were available in SA.[770]

8.23

In Western Australia:

The key findings from the 2004 national survey are consistent

with the earlier two state surveys and include:

- 53

per cent of patients could have been discharged if appropriate alternative

services were available and, of these

patients, 56 per cent required both appropriate intermediate

treatment/rehabilitation, support and

accommodation services.

- 51

per cent could have been discharged if appropriate support and accommodation

services were available.[771]

Responses

to acute bed shortages

8.24

There was a strong call from witnesses for additional

acute care places, to respond to current shortages. However the Committee's evidence strongly

suggested that the key cause of acute bed shortages is the lack of appropriate

emergency responses; a rehabilitative focus in acute care; interventions at

other levels, particularly step up and step down and respite beds; clinical

services in the community; and housing and employment supports. Each of these

needs strengthening and expanding to reduce the need for acute care over the

longer term. The Australian Mental Health Consumer Network recommended:

That the call for

‘more acute beds’ be understood in relation to the lack of

alternative modes of service delivery.[772]

8.25

Dr Freidin,

President of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists

said:

Increasing the number of hospital beds is not the sole answer

either. We need to have an adequate number of outpatient and community services

across the public and private sectors and these need to be integrated with all

other forms of support. We say that most mental illness is treatable, as

demonstrated by the increasing body of evidence. The inability of people with

mental illness to get appropriate help is one of the main barriers to the

provision of treatment. The treatments are available—it is just that the

service system does not deliver them.[773]

8.26

Ms Sheelah

Egan said:

... one hears calls for more beds instead of calls for much better

treatment in the community and more appropriate accommodation in the community.

Inpatient services are expensive, but could be minimised if sufficient

resources were put into the more efficient and cheaper community care.

(Unfortunately, in the past, community care has been treated as a cheap option.

Good community care is not cheap, but it is cheaper, for obvious reasons, than

inpatient care.)[774]

8.27

The Mental Health Council of Australia acknowledged

recent mental health funding increases announced by the Australian Government,

but commented:

...the next step is the most important: to use this funding to

build and strengthen the community based primary and secondary care systems

which will then take the pressure off the acute and crisis care services.[775]

8.28

The Council submitted that funding for acute care

should be limited to 25 per cent of any new funding.

8.29

All state and

territory governments' submissions stated that their budgets included funding

to improve inpatient services in coming years. In some jurisdictions this

funding related directly to inpatient services, in others it related to increased

'step down' facilities, supported accommodation and intensive community support

which would relieve pressure on inpatient services.[776]

8.30

In the short term, one strategy being used to lessen

pressure on acute care places is increased collaboration between the public and

private sectors. The Victorian Government commented:

Where public mental health services are operating at capacity,

it should be possible to make arrangements to use private mental health

services. For example, Victoria

has purchased acute inpatient beds from private mental health services to

manage periods of bed shortage.[777]

8.31

Healthscope Ltd saw opportunities to increase

collaboration between the sectors:

Although the private sector is primarily committed to providing

psychiatric services to privately insured patients, the private sector’s

ability to increase its capacity could be utilised to improve access during

periods of bed block. This could be achieved in a number ways:

-

Temporary

placement of patients requiring acute admission until a public bed becomes

available

-

Decanting of more

stable patients into the private sector as a mechanism of freeing up more acute

beds

-

Temporary

purchase of beds pending capital works

The basic economics of this solution

is compelling. A patient cared for in the Emergency Department for 24 hours by

an agency nurse will cost $1500 per day, when a bed could be purchased in the

private sector for approximately $500 per day.[778]

8.32

The committee supports innovative practices and

collaboration between sectors to respond to the pressure on acute inpatient

mental health services. However, investment in community-based care is required

to provide earlier interventions and in the longer term reduce the need for

acute services. The committee notes that in Trieste,

where there is strong community care infrastructure, it is rare for all the

psychiatric beds in the general hospital to be occupied (see Appendix 3).

8.33

Expansion of community services is not simply an issue

of cost effectiveness. It recognises the need to increase people's experiences

of mental health and where possible reduce the severity of illness experiences.

Rather than investing only in responses to acute episodes of illness, resources

are required to, wherever possible, prevent people's mental health

deteriorating to a situation requiring acute care. Following acute phases of

illness, adequate rehabilitation and support services are required to help

promote stability and wellbeing, and minimise the need for readmission.

Long stay care

8.34

While much of the evidence presented to the committee

about inpatient services concerned the pressures on short-term acute beds,

submissions also canvassed the issue of long-term care for the relatively small

number of people who are severely and chronically disabled by mental illness.[779] Witnesses observed that keeping

long-stay patients in hospital, because of a lack of alternative services, only

contributed to the strain on acute care places.

8.35

In 1992, the National Mental Health Policy recognised

that long-term care would be required for some consumers:

It is recognised that too much resource emphasis is currently

given to separate psychiatric hospitals. In some cases it may be both possible

and desirable to close them and replace them with a mix of general hospitals,

residential, community treatment and community supported services. However, a

small number of people, whose disorder is severe, unremitting and disabling,

will continue to require care in separate inpatient psychiatric facilities and

these facilities will need to be maintained or upgraded to meet acceptable

standards.[780]

8.36

However, the committee was told the NMHS has failed to

make appropriate provision for the care of these consumers.[781] Dr

Simon Byrne

outlined the kinds of services needed for chronically disabled consumers:

...it is possible to foster and develop long-stay wards with a

rehabilitation focus. Such services should be co-located with acute hospital

wards, partly because of the economies of scale involved in providing the

necessary support services and partly because of the need to rotate staff for

training purposes and to maintain morale when working with a very challenging

group of patients. The long stay services should have a rehabilitation focus

and have continuing active links with a variety of community services including

community residential services; thus all patients should be regarded as

potential candidates for community living, although the work necessary to

achieve this may take very long periods of time and may not always be

successful.[782]

8.37

Dr Philip

Morris outlined a similar approach:

We are suggesting that we need a substantial build of supported

accommodation. This is not accommodation where someone pops in to see a patient

once a day or whatever else. This is accommodation that has 24-hour nursing and

an appropriate level of support—medical, nursing, occupational therapy and

social worker support for patients. If you start doing that, you are getting

back to needing clusters of homes. They can be in the community, but they need

to be together. You will need to have them together because you cannot have

individual services going out because it is not efficient. We will get to

something like having properly based facilities that look different to the old

mental hospitals but, nonetheless, the services will be brought back to bear in

a sophisticated and specialised way. That will take some time. That is where we

need to go and that is the glaring omission at the moment: the longer stay

accommodation for people who cannot get back to independent care in the

community.[783]

8.38

While some submitters vehemently criticised the

implementation of deinstitutionalisation,[784]

a return to institutional-based care was not generally considered an

appropriate or advisable course for patients requiring long-term care.

Witnesses pointed to the stigma, isolation and lack of resources associated

with institutional care in the past.[785]

Reports have highlighted the abusive practices, discriminatory cultures and

lack of accountability which occurred in psychiatric institutions. Rather,

witnesses to this inquiry described the need for specialised community-based or

co-located services designed specifically for the long-term rehabilitation of

people severely disabled by mental illness.

Quality and effectiveness of

treatment

8.39

The committee received some graphic and alarming

evidence about inpatient treatment experiences. Assault and abuse of people

with mental illnesses still occurs within hospital settings. Discriminatory and

stigmatising attitudes and procedures remain.

8.40

The committee acknowledges that this inquiry has not

systematically reviewed all inpatient experiences and that some positive

experiences were also reported.[786]

However, the committee is disturbed that after many years of reform, abusive

and discriminatory practices remain evident. The following contributions

reflect some such experiences:

Another occasion was when the young man's mother and brother

visited him and he asked his brother to look at his room. They reached the room

to find a large 6ft male lying on his bed. The patient got a shock and was

clearly disoriented and went to another room and kicked some blocks around. A

nurse brought him back to his room and he appeared very frightened when the

nurse ordered a syringe. His brother asked what it was and was told that it was

"like liquid valium". A

doctor and two security men stood over him either side of his bed. Staff asked

the mother and brother to leave the room but they chose to stay and in front of

those people the patient's pants were pulled down and he went into a foetal position

because it was invasive and he was scared, as he had been a victim of rape. The

inhumane treatment raises the question of how and what was being done when no

family member was present. The patient was then told he could go and have

lunch. He left crying.[787]

......

Seclusion and restraint are used inappropriately and without

proper regard to the person. A client of our service was stripped naked and

thrown in seclusion for 12 hours when she had a known history as a victim of

sexual abuse. Clients report experiences of seclusion, terrified and left alone

for long periods of time with frightening psychotic symptoms. Seclusion is used

far more on weekends when no programs are

available.[788]

......

Instead the two security guards who arrived jumped me, threw me

to the ground and proceeded to beat the living daylights out of me. I was

repeatedly punched to the left eyebrow and as I wear an eyebrow ring, punching

the metal onto bone was exceedingly painful. I was repeatedly punched to the

right cheek bone. One of the guards twisted my elbow as far as it could be and

then brought his fist down onto my elbow with maximum force. This was done

several times. Both guards also bent my hands back at the wrist as far

backwards as they would go. I thought they were going to break them. I was

kicked in the base of the spine several times...I was kicked in the legs repeatedly.

I was punched in the chest and stomach repeatedly. One of the guards grabbed my

hair and drove my face forward into the ground, hurting my nose. He then pulled

my hair back the other way and repeatedly smashed the back of my head into the

hard, vinyl floor.

Throughout the attack I continued to scream and struggle, but

this was because I was in extreme agony. One of the guards put his hand around

my throat and squeezed to the point no air could enter or leave for at least a

minute. I was sure at that moment he was going to kill me. I could barely speak

for days afterwards.

The actual nursing and medical care I received ... was outstanding

so I have no idea why these nurses let the attack go on so long, although one

of the guards did lean over me at one point and whispered into my ear, “the

nurse can’t see what I’m doing from here and you’re fucking dead meat”. He also

laughed and smiled throughout the attack – he was clearly enjoying himself.[789]

......

On arrival [in the 'time out room'] I was ordered to strip all

clothes off. The situation was getting more and more bazaar [sic]. I thought I

was in hospital because I was sick and needed care. Is this the care that I

needed?

I told him "you've got to be joking".

He disappeared for a few minutes and came back with five other

nurses. They stripped me naked and put me into pyjamas. I can still see a big

guy with tattoos smiling all through the whole thing.

At no point did I abuse anybody or become violent. Why was I

getting such heavy-handed treatment when I don't think I deserved it.

After the nurse in charge pushed me into the back of the room

they locked the door and turned off the light. There was only a mattress on the

floor and the only window was in the locked door. If you have any iota about

psychosis you could imagine what was going through my head.[790]

8.41

Ms Isabell

Collins, Director of The Victorian Mental

Illness Awareness Council asserted

that damaging treatment experiences are common:

Having worked in the

public mental health care system for some 15 years, I am yet to meet a patient

of mental health who has not been damaged by the way he or she was treated and cared

for. Indeed, consumers will often say that it takes a good 12 months to recover

from hospitalisation just because of the way they were treated.[791]

Put simply, the current standard of practice is to contain

people with medication and then discharge them. That is all we do.[792]

8.42

Consumer

researcher Ms Cath Roper said:

I had 13 hospitalisations—all

of which were involuntary—yet I cannot look back and say that those were

healthy for me. There was extremely traumatic forced treatment involved in each

of those hospitalisations.[793]

8.43

The

Australian Mental Health Consumer Network recommended:

That government takes

seriously the consumer warning that some acute experiences leave people

psychologically scarred, sicker and more dependent in the long term.[794]

8.44

There have been some reviews of inpatient services and

changes that have been implemented to improve service standards.[795] The committee also heard the reality

of the complex situations hospital staff are required to deal with. For

example:

When he was again admitted to Maroondah Hospital psych ward my

son had a 3 week old untreated fractured leg gained after clinging onto and

being thrown from a car; he was taken to William Englis hospital emergency ward

after the incident but would not remain stationary for long enough for the cast

to be applied. There were several prior attempts seeking admission over

preceding months mainly due to violent and abusive behaviour.

During this stay in Maroondah hospital my son broke another

patients arm.[796]

8.45

Humane and professional responses are needed in what

can be complex and difficult situations. The personal experiences shared with

the committee show that in some areas inpatient service standards need to

improve.

8.46

Mr Graeme

Bond submitted that quality standards are

required:

When investigating my son’s treatment I sought to compare it

with any standards I could locate. I was able to locate very few publicly

accessible standards published by the Department of Human Services and resorted

to statements made by leading academic psychiatrists in a locally published textbook

of psychiatry.

There should be a comprehensive set of standards readily

accessible to carers and patients so that they can assess the care given

against an objective benchmark. Such standards should be the reference against

which actions of clinicians and services are judged, particularly in such forums

as the Coroners court.[797]

8.47

Observations by the Victorian Auditor-General are

pertinent:

The current set of mental health measures and key performance

indicators (KPIs) do not provide sufficient information to management and the

Government to measure the effectiveness of the services being delivered. Most

of the current measures and KPIs are not tied to departmental objectives and

relate to service delivery (i.e. outputs) rather than consumer outcomes.[798]

8.48

Acute care in hospitals needs to be guided by standards

of care that are focused on consumer outcomes, and which take a view beyond the

points of admission and discharge. This is important because issues raised with

the committee extended beyond acute care to the emergency departments where

admission took place and to discharge.

Emergency departments

8.49

While hospital emergency departments are one of the few

health services available to people with a mental illness on a 24 hour basis,

seven days a week, the environment is not necessarily therapeutic and treatment

may not eventuate. The NSW Nurses' Association commented that it was not

uncommon for mental health patients to wait in the emergency department for up

to five days before a suitable bed became available.[799]

8.50

The ARAFMI National Council Inc described the detrimental

impact of waiting in emergency departments:

The consequence can be that the consumer becomes acutely unwell

needing emergency treatment possibly though a hospital emergency service. If it

is then accepted that the consumer needs psychiatric care in a psychiatric

facility there are frequently no beds available and the consumer is kept in a

"holding" situation pending a bed becoming available, This is not

only detrimental to the consumer but also causes distress and anxiety to the

carer.[800]

8.51

Mrs Jan

Kealton described the void in emergency

departments services for psychiatric patients:

Once there you wait and wait and eventually you might get lucky.

... They take the person through to the triage area and tell them to sit in one

of the blue chairs. The chairs are near the reception area, and then there are

all the beds with curtains around them and so on. If you are a bit forceful,

like me, you say, ‘Excuse me, but I am going too,’ and then you, the mother,

are also allowed to sit on one of the blue chairs.

The blue chair is not in the treatment area and it is not in the

triage area, so you just hope that someone notices the person if they are

becoming distressed. You can walk straight out the door—if you do not have your

mother with you being nice to you and begging you and bribing you to stay—and

not get any treatment at all. Nobody would probably even notice. They are too

busy handling all the blood and gore, the heart attacks and those sorts of

things to go to somebody who looks perfectly normal, sitting there fidgeting ...

We have sat there for seven hours on a number of occasions...[801]

8.52

The NSW Nurses' Association described the hectic

environment of hospital emergency departments. They noted that it is not

possible in this environment to establish rapport with patients and initiate

preventative interventions. The Nurses' Association also pointed out that the

'excessive stimulus generated by the chaos and pressured atmosphere in the

department' itself can contribute to escalating behaviour. They stated:

Given that security personnel are engaged to provide supervision

for such volatile patients, it is clear that restraint and sedation are the

likely and foreseeable outcomes... This is an untenable situation for all

concerned.[802]

8.53

The committee heard that people with acute mental

illnesses are particularly vulnerable to breaches of their privacy and dignity

within the emergency department environment. Dr Georgina Phillips said:

Their ED management is usually

carried out in a high acuity, highly visible cubicle in the central part of an ED

work area (so that medical and nursing staff can closely monitor them). Many in

the ED usually overhear their conversations:

staff, security officers, other patients and their relatives. Many observe their

appearance and behaviour, and if containment and restraint is required then

this is usually carried out in full view of the rest of the ED.

This affects not only the mentally ill patient, but can cause distress and

potential physical harm to other patients or relatives in the ED.

These are daily occurrences in EDs, however few would have space or resources

to devise appropriate strategies to provide better and safer care.[803]

8.54

A report by the South Australian Ombudsman points to

some of the underlying resource issues creating strain on emergency

departments:

It appears that neither the existing mental health system or

supporting resources were sufficient to accommodate the significant changes

undertaken in this State, in line with the National Mental Health Strategy...

Moreover, there was overwhelming evidence during my inquiry from medical

practitioners and others that there has been a significant increase in numbers

of mental health patients presenting at emergency departments. This clearly,

has placed undue strain on junior medical and nursing staff who are left to

manage the increasing numbers of patients in crisis in emergency departments.

A common consumer and staff concern was the need to provide a

safe and stable environment for mental health patients in crisis and in the

community. It was apparent that in most emergency department environments staff

face difficulties in separating highly agitated patients and there is an

abundance of evidence that has shown that enormous pressure has been created at

times when there has been an acute shortage of available beds in psychiatric

wards and on discharge for either the emergency department or an inpatient

facility, with a distinct lack of support in the community.[804]

8.55

Several submitters recommended specialised emergency

departments for people experiencing mental illness.[805] Dr

Philip Morris

told the committee:

...patients that have been sent to emergency departments do not

get the best of care because the facilities are not providing unique services

for patients with mental illness. What we advocate now is a parallel—not a

separate but a parallel—program of emergency departments located in the setting

of the general health sector for patients with psychiatric illness. Some of

these things are now starting to happen in Australia.[806]

8.56

The New South Wales Government described a trial of

such services:

Psychiatric Emergency Care Centres (PECCs) have been

successfully trialled at Liverpool and Nepean

Hospitals. These PECCs have

resulted in a reduction of the average length of stay in Emergency Departments

for psychiatric patients. The PECCs are dedicated services, situated adjacent

to the Emergency Department, staffed 24 hours a day, 7 days a week by mental

health specialists for emergency assessment and treatment of people presenting

with serious mental illnesses.[807]

Discharge processes

8.57

Discharge from hospital can be as abrupt as admission

can be slow. Submitters told the committee about a lack of discharge planning

and continuity of care after discharge from hospital or the emergency

department. Poor discharge planning and insufficient community-based services

can leave consumers in inadequate environments without appropriate therapeutic

care, resulting in increased symptoms and possibly re-admission. Following an

acute episode of illness, the risk of suicide is highest in the first weeks

after discharge.[808] Where families

and carers are contacted and available, early discharge increases their burden

in providing care and support.

8.58

Dr Philip

Morris said:

Because of the pressure on bed numbers, patients are being

discharged before they are ready to go home. That leads to harm both to them

and to their families and the general public. If we had more resources,

patients could stay in hospital for longer and be treated to a point where they

were much more ready to be discharged. I am not just talking about discharge

from acute services. There is no opportunity at the moment to put many patients

into longer term facilities where they can be rehabilitated and recover further

so they can then go back into the community in a decent state.[809]

8.59

Dr Morris

also suggested there is evidence that some practitioners are having patients

placed under involuntary treatment orders as the only way to obtain follow up

treatment in the community after discharge.[810]

8.60

Mr David

Webb shared his discharge experiences with

the committee:

On the strength of that assessment, the psychiatrist judged that

I suffered from what he called existential depression and that I did not need

to be there. I had attempted suicide just a couple of nights before. He told

the social worker and the charge nurse to arrange for my discharge. That was

it. The psychiatrist spoke to me about where I would go on discharge and

whether I had somewhere to go. I did not have a place to go as I did not have a

home in Melbourne at the time. He spoke to the social worker and said, ‘Help

him find somewhere to go.’ I left that hospital with the phone number for the

emergency accommodation of the Salvation Army. That was the discharge support

that I got a couple of days after a suicide attempt. People tell me that would

not happen these days, but I am not sure. I am one of the fortunate ones. There

are a lot of people that have been through that experience and they have gone

straight to the nearest railway line to jump under the first train.[811]

8.61

Carer's also described the lack of services post

discharge:

Another issue in regard to the post acute-care situation is that

in the case of our son’s first psychosis, I had to initiate post-hospital case

work. No-one offered me access to services. I had to seek these out and despite

my best efforts to have a case worker assigned while our son was still in

hospital to facilitate a smooth transition on his discharge, it proved a

fruitless exercise. I knew nothing about mental health services and no-one

offered me any help or information. It concerned me enormously that if our son

had not had an active advocate in me, then he would have been discharged, unwell,

and having to fend for himself, with no accommodation and with no knowledge or

ability to access social welfare let alone any mental health services (as inadequate

as these turned out to be).[812]

8.62

Ms Isabell

Collins commented on the ethical dilemmas

facing staff who make discharge decisions:

Certainly psychiatrists have said to me that they are constantly

in this ethical dilemma where they have somebody who is really sick and needs

admission to hospital and they have somebody in hospital who is still sick but

not as sick as the one who needs to come in. They have to juggle and take these

risks. What happens is that they do take the risk. They send them out into the

community where there are no supports for them.[813]

8.63

Reviews of service standards indicate that the personal

anecdotes shared with the committee are illustrative of systemic failures. A

file audit by the Auditor-General in Victoria in 2002 found that 89 per cent of

consumers reported that they were discharged while still acutely unwell, with a

high level of need for ongoing support. Yet none of the discharge plans

reviewed met all required standards.[814]

8.64

Among the disturbing findings, the Auditor General

reported:

-

30 per cent of discharge plans reviewed showed

no evidence that consumers had been linked into appropriate community-based

services for ongoing treatment following discharge;

-

In 80 per cent of cases there was no evidence

that consumers were consulted in the formulation of the discharge plan. Family

or carers collaborated in discharge planning in only 15 per cent of reviewed

cases;

-

In only 16 per cent of the reviewed plans was

the consumer given emergency contact numbers; and

-

In only one per cent of cases reviewed was a

copy of the discharge plan actually provided to the consumer.[815]

8.65

Even where services specifically focus on discharge

planning with dedicated resources, evidence suggests that actual follow up remains

limited. A study of the emergency department of a Sydney hospital, which has a

dedicated Mental Health Liaison Nurse, found that 86 per cent of consumers felt

that adequate arrangements had been made with them before they left emergency

and 71 per cent were referred to a community mental health team on discharge.

However, only 63 per cent actually had contact with the community mental health

team after leaving emergency.[816]

8.66

The committee suspects that the lack of discharge

planning and support, at least in some cases, reflects the fact that acute

service providers know there is nowhere for the person to go. The Mental Health

Council of Australia submitted:

Consumers are often discharged without any rehabilitation plan

or even reference to appropriate places because the discharging services knows

these services have no capacity to accept further referrals.[817]

8.67

This situation reinforces the concern, expressed

throughout this report, that the mental health sector in Australia

currently lacks a full spectrum of care.

8.68

One possible consequence of inadequate discharge

planning, follow up treatment and care is the deterioration of a person's

mental health, which results in readmission. This is an unsatisfactory

situation for all involved, with consumers carrying an increased burden of

illness, carers suffering increased strain, and services sustaining repeated

costs. Even in Victoria,

a state with above average investment in mental health services and one of the

highest per capita investments in community-based care,[818] readmission rates remain high. In

2005 the Victorian Auditor-General reported that although initiatives had been

implemented since 2002 to increase community-based care, and more patients were

being contacted in the community before and after admission for acute care, an

increasing proportion of patients were being readmitted within 28 days of

discharge.[819] In the June

quarter 2005, 17 per cent of mental health patients were readmitted within 28

days of discharge.

8.69

This level of readmission suggests that community

supports remain inadequate to stabilise and support people with a mental

illness following acute episodes. However, the data might also suggest that at

least hospitals remain an accessible service for people requiring further care,

with people being readmitted rather than turned away.

Crisis services

8.70

Crisis services refer to services designed to respond

to mental illness related emergencies in community settings. Such services can

save lives and are particularly valued by carers. Crisis assistance needs to be

timely to be effective, and achieving prompt crisis response is a challenge

facing these services, which appear to be constrained by resources as well as

perceived safety issues.

8.71

A key issue regarding crisis services is the need for

services to attend and assist crisis situations out of business hours. Ms

Sharon Ponder

remarked on this need:

Apparently acute episodes of schizophrenia occur at the most

"inconvenient" times for our system, It needs to be told that an

acute schizophrenic episode is rarely "convenient" for the sufferer,

never mind the system.[820]

8.72

The lack of after hours mental health services means

that hospital emergency departments and emergency services (police and

ambulance) are often the only available services out of business hours. These

services are not necessarily trained or equipped to deal with mental illness

crises, and can create further distress for people experiencing mental illness:

The response from the mental health services to after hours

crisis is that the refuge phone an ambulance to take the young person to

accident and emergency or call the police, this of course creates a scene in

front of other young people and neighbours, not to mention the trauma for the

young person involved.[821]

8.73

In some areas, after hours phone calls to psychiatric

units are simply referred to Lifeline.[822]

Lifeline commented that its services are over stretched:

Lifeline...has become a defacto after hours mental health service

with volunteers answering call after call from people with a mental illness

that have been referred to Lifeline from other mental health services unable to

cope with high levels of demand. Lifeline is not adequately equipped, resourced

or developed to fulfil this role appropriately. Many of our traditional crisis

callers have not been able to access our service because of the dominant usage

of some mental health callers. With over half a million calls per annum being

answered by Lifeline volunteer telephone counsellors it is clear that this is a

significant community problem.[823]

8.74

Lack of services after hours for people experiencing

acute mental illness therefore impacts not only on mental health consumers and

their carers, but also on wider service providers and their clients.

Crisis assessment and treatment

teams

8.75

One service designed specifically to assess and

intervene during episodes of mental illness are mobile acute assessment and

treatment teams. These teams are 'medical health services which provide

home-based assessment, treatment or intervention primarily for people experiencing

an acute psychiatric episode and who, in the absence of home-based care, would

be at risk of admission to a psychiatric inpatient service'.[824] The services are known by different

titles across jurisdictions, including 'psychiatric crisis intervention' services,

'community assessment and treatment' services and 'crisis assessment and

treatment' (CAT) services.[825]

8.76

The National

Mental Health Report 2005 describes the essential characteristics of these

services as their 24 hour, 7 day per week availability and focus on short-term

intervention. However, carers lamented how often they were unable to obtain

assistance in crisis situations. Several submissions commented that the poor

response record of the Crisis Assessment and Treatment teams had earned them

the nicknames 'Can't Attend Today' teams or 'Call Again Tomorrow' teams.[826] If the CAT teams are to be effective

and supported by consumers and carers there is a need for better resources and

training.

8.77

One submitter described the frustration of the lack of

service, as follows:

...if they are contacted it means that the client or family, or

both, needs some help. Instead, you often get this indifferent response, trying

to get you to go away as your crisis doesn't fit their criteria. I have even

been told that I couldn't be helped because they were too busy with other more

urgent matters. This was before I was even listened to...In fact, they have never

made a trip for us. The only times I have received help was if my son could be

calmed down enough to let me drive him to hospital. If all else failed, I had

to call an ambulance.[827]

8.78

Mr Graeme

Bond reported his experience with the CAT

team:

Even when I have called reporting the most alarming behaviour

which posed a threat to my wife or, on occasions to me, I have been unable to

have a CAT Team attend. Indeed, in my area, I believe that after about 7:00pm the CAT Team is one person accessible by

a paging service.

The standard advice offered, in response to a request for a CAT

Team, is 'call an ambulance' or 'call the police'.[828]

8.79

The Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council

presented strong criticism of CAT services:

Crisis Assessment and Treatment teams (CATT)

are probably the best example of what happens when governments fail to

adequately fund services.

From the consumer perspective CATT would be the

most disliked and criticised service in mental health.[829]

8.80

However, the CAT team model is effective when

adequately resourced:

Whilst living in the ACT, we experienced excellence from the

local CATT which attended our home when our daughter was in a

prodromal state and had locked herself in her room late at night. As a result

of the CATT dedication, a humiliating and extremely

distressing family situation was brought under control without need for

hospitalization or the stigma of well-meaning but untrained police presence in

our neighbours' presence.[830]

8.81

Even with well resourced prevention and intervention

programs, the severe and episodic nature of some mental illnesses means that

crisis situations can occur. Without ready access to personnel adequately

trained and experienced in intervention and de-escalation, crisis situations

can end in tragedy:

I have just been involved in a coroner’s inquest. A young

23-year-old man had been shot dead by the police. He had an agreement with his

parents, before becoming unwell, that should he become unwell they would ring

the CAT team. He became very unwell and that was not the case. He had knives

and he hurt his father. The location was secured and his mother was terrified

her son would be shot. She told the police: ‘He is all right. He will be able

to talk. Please be careful of him.’ The police did everything in their

endeavours to get the CAT team. The duty person for the CAT team on the evening

of that night, when the police called, did not perceive that they were being

asked for assistance. They gave the response: ‘Yes, this person has been in

this hospital. Yes, this person does have a diagnosis of schizophrenia.’ But

they did not then go on to say, ‘And this person, in fact, has asked before to

be killed.’ So the police, acting as they believed they should, managed this

situation. Something really unfortunate occurred: the young man appeared behind

the house and came at a police officer with knives and the consequence was he

was shot.

At the coroner’s inquest, the CAT team thought that the

provision of the information I have just provided to you was enough to give

instructions to the police in how to take control of the situation and the

young man. The police do not have effective training in de-escalation; their

training is in control, not de-escalation. My submission is that when you have

the police ineffectively prepared, and when you have the CAT team not

perceiving that they need to attend and, further, saying that they would not

attend if their health and safety were in danger, then even if the police could

make their health and safety secure we either have to do something about the

function of the CAT teams or do something about the education of the police.[831]

8.82

As illustrated it the above example, coordination

between crisis teams and the police is essential in responding to crisis

situations involving mental health consumers. The role of police in mental

health services is discussed further in Chapter 13.

8.83

There is a need to ensure effective responses for

people with mental illnesses requiring emergency attention. CAT teams currently

have limited availability and are concerned about attending potentially violent

situations. Emergency departments, while always open, are stretched and do not

necessarily provide an environment or interventions appropriate for acute

mental illness. Similarly, while emergency services such as police and

ambulance will attend mental illness crisis situations, they are not trained to

respond effectively to psychotic episodes and their presence can escalate the

situation.

8.84

One of the NSW Government's initiatives is to improve

emergency mental health responses is the establishment of a 24-hour 1800 phone

number for each NSW Area Health Service.[832]

It was not clear from the NSW Government's submission the extent of the

services that would be offered via this phone line. However, a single 24 hour

access point for mental health emergencies may assist carers and consumers who

currently report a desperate need for assistance. The Council of Australian

Governments' proposed National Health Call Centre Network[833] may help meet this need, if

adequately resourced to include dedicated mental health professionals and

backed up by available intervention and treatment services.

8.85

Two points stand out in discussion of crisis services

for mental health. First, the very nature of mental health crises often means

that it is quite inappropriate for police or ambulance to respond. Mental

health crises need a mental health response. Being told to 'call the police' in

particular often seems to be inviting the escalation of a situation that need

not necessarily deteriorate. Second, better community-based care and support

would almost certainly mean less crises in the first place.

Contrasting experiences

8.86

Some witnesses expressed a view that evidence presented

to the committee may overly represent negative experiences:

The inquiry will receive a great deal of anecdotal evidence

about the inadequacy of services. For various reasons, the inquiry is unlikely

to hear from people who are satisfied with the service. For example, stigma is

still so great, people who are coping reasonably well will not want to draw

attention to themselves.

Anecdotal evidence can be out of date. Situations can improve or

deteriorate quite rapidly. It can come from people who are so shocked, angry or

distressed and who wish to find some one or something to blame. Two families

can have much the same experience and describe it in quite different ways.[834]

8.87

The Victorian Government commented on the nature of the

inquiry:

The methodology focuses on subjective measures such as

submissions and public hearings which will elicit public and expert opinions

from those who choose to submit, but will be limited if this information is not

balanced by objective evidence of systemic issues regarding state service

provision.[835]

8.88

It is difficult to reconcile this view with the

Victorian Government's own submission which states that the operating

environment in Victoria is one of 'sustained demand pressure', with 'services

operating over capacity, as evidenced by high community caseloads and chronic

acute bed blockages' and 'crisis driven service responses, difficulties with

service and bed access, 'revolving door' clients....and a significant impact on

other social policy areas'.[836]

8.89

There is evidence that confirms that systemic issues

underlie the personal experience of mental health services. Anecdotal

experiences of inpatient and crisis services are consistent with service

reviews, such as the Victorian Auditor-General's finding that:

Increasing service demand and associated levels of unmet demand

are resulting in service access difficulties for many consumer, early discharge

from hospital, and increased burden on family and carers. These outcomes

increase the likelihood of future unplanned re-admissions.[837]

8.90

The NSW Auditor-General similarly remarked:

The increase in demand for emergency mental health services has

offset many (and perhaps all) of the gains from funding increases. The system

is under considerable pressure, and patients can face lengthy delays before

being admitted to a bed.

It is important that services work together to share resources

at times of peak demand. Yet, there are times when the availability of mental

health beds means that some patients face being transferred very long distances

to access an acute mental health bed.

There is also evidence that some patients spend inappropriately

long periods in emergency departments while awaiting acute mental health beds

or are discharged from the emergency department prior to a bed becoming

available.[838]

8.91

The dearth of outcome reports in the mental health

sector also means there is little ongoing, systematic assessment of the actual

health outcomes provided by mental health services. There is generally no data

to contradict many of the systemic issues illustrated by personal anecdotes to

this committee.

8.92

Hearing personal experiences and reporting individual

concerns does not belie the substantial reforms that have occurred, the

systemic deficiencies that remain and the concerted and coordinated effort

required to continue to improve mental health services. The Victorian Government submitted:

A number of [the inquiry] terms of reference sit well outside

the mandate of the specialist mental health system and will require vigorous

and sustained effort by many different areas and levels of government,

including the Commonwealth Government, to address.[839]

8.93

The committee certainly assumes that all levels of

government are committed to making the 'vigorous and sustained effort' required

to improve mental health services, and ultimately the mental health of all

Australians.

Concluding remarks

8.94

There are serious problems facing people with mental

illness who find themselves seeking, or being placed in, acute care. There has

been some discussion of whether these problems are a result of the way in which

the policy of mainstreaming has been implemented. Mainstreaming was intended to

involve the replacement of stand-alone psychiatric facilities with a pattern of

brief admissions to acute psychiatric wards within general hospitals backed up

by community-based care of varying types. However, for many consumers this has

not been the reality.

8.95

A key criticism has been the apparent inability of

mainstream services to meet the specific needs of mental health consumers.

Submitters pointed to the need for tailored treatment and for the treatment

environment to be conducive to recovery:

The other point I would like to make in the broad sense is that

mainstreaming has failed. Mainstreaming was the idea that you bring all mental

health services under the one umbrella of general health and somehow this means

that all discrimination goes away. But that is not the case. There is some

reduction in stigma. One of the good things about mainstreaming is that it

recognised the role of general practitioners. But what it has not done is

maintain a focus on the unique needs of patients with psychiatric illness.

Because of this loss of focus we now have, for example, inpatient units being

built with no space. Psychiatric patients need space. When they are very unwell

they are agitated, they are sometimes very sensitive to others and they need

room.[840]

8.96

Dr Scott-Orr

argued for 'co-located' services, in which psychiatric services share medical

resources with general hospitals, but retain a separate environment and

specialised care:

It is my view that general hospital architecture and functioning

does not lend itself to mental health care. Nor does the recent design of

mental health units in general hospitals give me any hope or joy. I consider

the place(s) of round the clock mental health care should be readily accessible

by walking, to and from the relevant general hospital, and sharing its resources

for all sorts of medical reasons and economies.

It needs to provide a 'homey' environment, with that look and

feel, in which people are up and about in street clothes, preferably to have

its own street address, while having provision for some secure area and ready

observation where needed.[841]

8.97

On the other hand, the Royal Australian and New Zealand

College of Psychiatrists strongly supported mainstreaming:

We should progressively move to integrate mental health into

general health. There are enormous advantages in having the majority of

psychiatric services in general hospitals as part of the culture of general

hospitals with regard to constant review and quality improvement and in the

accessibility of general health care to patients with mental illness as well.

There is probably going to be a need for small specialist services for people

with particular disorders where all they need is psychiatric intensive care,

but I would see that as being a very small part of the much larger integrated

system.[842]

8.98

The committee accepts the argument that bringing acute

psychiatric care into a mainstream hospital setting helps ensure quality

treatment for all of a patient's health needs, and can have workforce and

management advantages. Effective acute care, however, needs to involve higher

standards of care and the provision of facilities that meet the specific needs

(such as open space and a more home-like environment than is typical for a

general hospital) of people with mental illness. Above all, these need to be

linked in to community-based services, before admission and after discharge.

8.99

There is now a substantial body of evidence before this

and other recent inquiries to show that inpatient and crisis mental health

services have severe shortcomings. Services have failed to meet the standards

Australians should now, after many years of inquiry and reform, be able to

expect.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page