Chapter 6 - Access to mental health services

6.1

Access to mental health services was a key issue for

the inquiry. This chapter deals with the role of mental health professionals,

workforce training and shortages and their uneven geographical distribution, government

initiatives intended to overcome these problems, barriers to utilising allied

mental health workers and alternative models of primary health care.

Workforce issues

Psychiatrists

6.2

Psychiatrists are medical practitioners with a

recognised specialist qualification in psychiatry.[441] They work in public hospitals, community

mental health services, private hospitals, and in private practice. The Royal

Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) stressed the

importance of their leadership role:

Psychiatrists are uniquely placed to integrate aspects of

biological health and illness, psychological issues and the individual’s social

context. They provide clinical leadership with many working in

multidisciplinary team settings. Psychiatrists treat patients and work with the

patient’s general practitioner, other health care providers, families and

carers of patients, and the general community.[442]

6.3

Access to psychiatrists is however very limited. The Australian

College of Psychological Medicine

(ACPM) submitted that private psychiatrists were largely inaccessible because

few bulk-billed, most are located in metropolitan areas and too few psychiatrists

are employed in the public sector. ACPM pointed out:

Most [public psychiatrists] are too busy coping with acute

crises to be able to become pro-active in prevention and early intervention.

Most have no time to deal with the high prevalence disorders such as anxiety,

depression, personality disorders and drug abuse, in the main treating the

individually very demanding schizo-affective range of disorders. [443]

6.4

The RANZCP itself said; 'There is clearly a discrepancy

between the available psychiatric workforce and the mental health needs of the

population'[444]. Dr

Martin Nothling,

a psychiatrist representing the Australian Medical Association (AMA), said this

shortage translated into long waits for patients to see psychiatrists:

...in many cases there can be delays of weeks or months before

someone can be seen because psychiatrists are literally so busy. It is common

talk at any psychiatry meeting you go to where you talk to colleagues—everyone

is booked out. How can you keep seeing patients? You cannot. ... You just

cannot keep adding on patients and working on into the night.[445]

6.5

Several witnesses commented that not many private

psychiatrists bulk-billed, putting access beyond the financial reach of many.[446]

Psychiatrist Professor

Ian Hickie told the committee that the out-of-pocket costs

of seeing a psychiatrist had risen by 49 percent since 1998.[447]

6.6

Difficulty in attracting young doctors to train as

psychiatrists was identified as a serious problem. The AMA indicated that many

psychiatric registrar training positions across the country are not filled by

trainees:

Psychiatrists are among the poorest paid of all medical specialties

and it is not attracting sufficient new entrants which will show up in serious

workforce shortages in later years.[448]

6.7

The Australian Medical Workforce Advisory Committee

found that psychiatry was one of a minority of specialisations in which fewer

people were training than had been recommended, and the only one showing a

decline in numbers.[449] Dr

Nothling told the committee how potential

trainee psychiatrists were put off pursuing a career in the field:

They go into these emergency rooms and they see how dysfunctional

they are. If you have a patient who is psychotic, what do you do? It is

extremely difficult. You spend a lot of time on telephones trying to find a bed

somewhere. You cannot get them in. The treatment they need is in-patient

facilities. They are not available. The emergency rooms get clogged up. The

young doctors see all that and they start thinking, ‘Would you want to be in

this area?’ That is a big problem. Many doctors who have said to me: ‘Look, I

wanted to be a psychiatrist,’ said that once they started to see how the system

was not working decided they would go elsewhere.[450]

6.8

Compounding the shortage of psychiatrists is their poor

distribution geographically, with the majority concentrated in urban areas. The

National Rural Health Alliance (NRHA) observed

that at the general hospitals outside of major urban centres that must deal

with mental health in-patients, there are few or no psychiatrists, and that less

than 3 percent of psychiatrists or psychiatrists in training work outside major

cities and inner regional centres.[451]

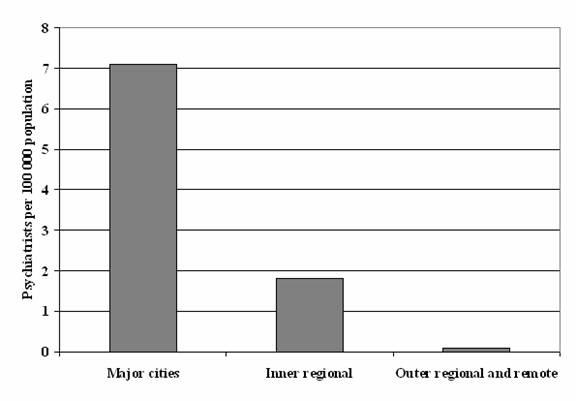

Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) indicates that

whereas there are 7.1 private psychiatrists per 100 000 population

practising in major cities, the equivalent figure for non-major city areas is far

less, with only 1.8 per 100 000 in inner regional areas, and less than 0.1

per 100 000 for outer regional and remote areas. (Figure

5.1)[452] Even within urban areas,

psychiatrists are more likely to be located in more affluent neighbourhoods.[453]

Figure 5.1 Number of psychiatrists per 100 000

population

6.9

Lifestyle appears to be a factor in the maldistribution

of psychiatrists. The RANZCP commented that psychiatrists liked to be close to

fellow psychiatrists to share information and for continuing education

programs.[454] Other evidence pointed

to problems with practising in small communities:

Unless you have a critical mass of psychiatrists on call ... you

are going to meet most of your patients in Coles and your kids

are going to be playing on the football team with some of your chronic patients

et cetera. So there are issues about living in rural communities for mental

health professionals generally that are tricky.[455]

6.10

Initiatives are being taken

to address the lack of psychiatrists in rural and regional areas. These are discussed

further in Chapter 16 in the context of the needs of rural and regional

Australians.

6.11

The practice of psychiatry came in for criticism for its

reliance on a medical model of treatment.[456]

Some witnesses said psychiatrists assessed patients and formed a diagnosis too

quickly and prescribed treatment that was all too often medication and/or

confinement, They were also criticised for not treating the patient with

respect and without taking into account the patient's perspective or broader

needs.[457]

6.12

Mrs Pearl Bruhn, with personal experience of the mental

health system, expressed frustration with the perfunctory treatment sometimes

received:

Psychiatrists, if you are lucky enough to see one, and not just

a medical officer, spend only 15 minutes with each patient, with time only to

discuss medication. There is no time to deal with the many other worries a

patient is likely to have.[458]

6.13

Others complained:

...psychiatrists knew that mania was a possible side effect of

many anti-depressant drugs but they weren’t apparently on the alert for it, and

they apparently did not know how to recognise it, or what questions to ask.

Even after I crashed, they had no idea how to deal with the aftermath, or how

to deal with the devastation caused except to write more prescriptions.[459]

6.14

The Mental Health

Foundation ACT was also critical:

Professionals, especially medical people, still hold power and

authority in our society. Psychiatrists are mainly educated in the medical

model of prescribing medication, but are not necessarily clued into the importance

of the relationship between themselves and their client, although this is

changing.[460]

6.15

The pressure in public hospitals, and emergency

departments in particular, contributed to what was seen as unsatisfactory

psychiatric treatment:

Many trainees are now forced to work on crowded, busy acute

adult inpatient units, where the disorders are generally restricted to three or

four diagnoses. The patients are chronic and almost impossible to treat and the

focus is mainly on the biological therapies.[461]

6.16

Obviously not all consumer experiences with psychiatric

treatment are negative. Consumer advocate, Mr

John Olsen, a

person with schizophrenia, described himself as 'one of the lucky ones' for

whom medication worked. He told the committee of his gratitude to a

psychiatrist (in a prison setting) who coerced him into taking medication, and

established him on the road to a stable life.[462]

Others referred to the positive experience of finding a 'wonderful

psychiatrist' whose care greatly assisted them or family for whom they cared.[463]

6.17

The RANZCP responded to criticisms of psychiatry by saying

that psychiatrists were working with a biopsychosocial model of care that was

consumer-centred:

In the clinical setting, the more information you can get about

someone’s social circumstances and social network and the involvement of their

carers and their families and their own views, quite simply the better able you

are to plan with them what needs to be done and then to implement a plan that

will be successful and acceptable to them.[464]

6.18

Dr Freidin

argued that inadequacies in psychiatric assessment and treatment are often the

result of factors beyond the clinician's control, agreeing that sometimes this

resulted in consumers and carers being marginalised:

We are also aware, though, that practically, in stressed,

under-resourced services, when people do start having to act fast to make

decisions more quickly than ideally they should—for a host of reasons—one of

the things that slips by the wayside is the time that should be taken

to consult in detail with family and with the patient before deciding on an

ongoing management plan. It is a little easier in private practice because one

is a bit more able to control the pace of things.[465]

Mental health

nurses

6.19

Mental health nurses work in public and private

hospitals, community mental health centres and teams, prison mental health

services, and in private medical practices. They are a significant part of the

mental health workforce: in 2001 there were 62.2 mental health nurses per

100,000 population.[466]

6.20

A joint submission by peak nursing representative

bodies, the Association for Australian Rural Nurses (AARN), the Australian and

New Zealand College of Mental Health Nurses

(ANZCMHN) and Royal College of Nursing Australia (RCNA), identified the current

nation-wide shortage of psychiatric nurses as critical, and affected the

ability of nurses to do their jobs properly:

The mental health nurse may be so overburdened by their workload

that they are unable to perform their roles to its fullest potential, and are

themselves being exposed to stress and anxiety. Staff going on leave,

especially in community services, are usually not replaced resulting in the

remaining staff not having the time to follow up all of their clients.[467]

6.21

This joint submission from nursing peak bodies also

pointed out that the workforce shortage is more marked in rural, regional and

remote areas:

There are a higher proportion of mental health nurses in the

capital cities and very low numbers in smaller regional and remote areas

(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2001). The shortage further

compounds the under-servicing of rural and remote locations.[468]

6.22

The numbers of mental health nurses in major cities,

inner and outer regional areas and remote and very remote are shown in Figure

5.2.[469]

Figure 5.2 Number of mental health nurses per

100 000 population

6.23

Submissions referred to the difficulty in recruiting

and retaining nurses in the field of mental health. The ageing of this

workforce was noted as a significant problem, with mental health nurse Mr

Jon Chesterson

observing that:

...the average age of the mental health nursing workforce is

47+, and more than half of the existing workforce is expected to retire within

the next 15 years. The pitifully small trickle of new graduates into mental

health today compared with the late nineteen seventies and early eighties has

already resulted in a workforce crisis.[470]

6.24

The Health Services Union pointed out that the bulk of older

nurses are graduates of the former direct entry psychiatric nursing courses.[471] Unlike their older colleagues, nurse

trainees today must first undertake a three-year generalist nursing degree (with

very limited content on mental health theory and clinical practice)[472], followed by post-graduate studies

in mental health nursing. Thus there is a reliance on generalist graduates

being attracted to pursuing further studies in mental health. The committee

heard that this was not happening to a sufficient extent. The NSW Nurses'

Association commented that 'the appeal of the sector to new graduates is

diminishing.'[473] Stressful working

conditions and significant levels of violence in the mental health workplace

were mentioned in several submissions as negative factors.[474] The AMA commented:

...nurses are not being attracted to work

in psychiatry because the system is dysfunctional and because of security

problems. It is a common theme across the nation that nurses and doctors

attending severely disturbed patients are being assaulted at a rate which

is causing concern and public discussion amongst these groups.[475]

6.25

A study of a psychiatric unit at one hospital in NSW

revealed high levels of violence and aggression, and pointed to the heavy toll

on mental health nurses:

[Psychiatric] Units where high levels of aggression and violent

behaviour are experienced in the workplace on a daily basis must be

acknowledged as dangerous workplaces. Staff work continuously under elevated

stress levels (physical, mental and emotional). Staff locked in [these] units

for eight hours per day for five shifts per week with aggressive patients must

pay a toll in some way. [476]

6.26

To address the problems of recruitment, the joint submission

from peak nursing bodies argued that mentoring in mental health nursing needed

to be provided to encourage already practicing nurses into the field, and that funding

incentives were also required:

It is ... important that appropriate funding be made available

for transition programs specifically for mental health ... for newly graduating

nurses coming into the workforce, to attract them into this specialty field.[477]

6.27

The shortage of mental health nurses has been the

subject of many reviews and studies. Submissions made reference to the 2003

report of the Australian Health Workforce Advisory Committee, Australia Mental Health

Nurse Supply, Recruitment and Retention.[478] This report made a number of recommendations

to address workforce shortage issues, including that an agreed framework for

mental health content in undergraduate general nursing degrees be developed.[479] The committee notes the recent

Victorian State Government Victorian

Taskforce on Nurses Preparation for Mental Health

Work Report (September 2005), which recommends, amongst other things, the trial

of a specialist university degree with a major in mental health.[480]

Psychologists

6.28

The greater role that could be played by psychologists,

particularly clinical psychologists, in Australia's

mental health workforce was a strong theme in the inquiry.

6.29

Psychologists, as defined by the Australian Institute

of Health and Welfare, consult with individuals and groups, assess

psychological disorders, and administer programs of treatment.[481] They do not prescribe medication,

and according to the Australian Psychological Society (APS), have spearheaded

the development of non-pharmacological treatments.[482] There are several different

specialisations within psychology, all requiring additional post-graduate study

and training. The APS advised of a number of specialist affiliated colleges covering

the fields of clinical, community, counselling, educational and developmental,

organisational, neuropsychology, and health psychology.[483] The committee received evidence that

psychologists can play an important role in the assessment and treatment of mental

disorders.[484]

6.30

The public sector is a major employer of psychologists,

particularly in community mental health teams. Yet evidence from representative

psychologist bodies suggests that psychologists in these teams are increasingly

employed in generic positions as 'case managers' or 'allied health workers', and

not providing psychological assessment and treatment for which they are

trained.[485] Many are too busy dealing

with clients with serious mental illness to be able to provide effective early

intervention 'upstream' treatment, or to provide treatment to those with high

prevalence disorders such as depression. The Victorian Section of the APS

explained:

Mental health services are currently only available to those

with the most severe mental health disorders. Many people suffering from

complex and disabling psychological problems, including disorders of high

prevalence, are unable to access psychological treatments in the public mental

health sector, despite evidence of their effectiveness. In addition, the long

waitlists and increasing caseloads present in continuing care mental health

teams mean that little or no opportunity is available for clinical

psychologists to provide early intervention and relapse prevention.[486]

6.31

Clinical Psychologist Dr Jillian Horton

argued that public mental health services should maintain the capacity to

provide psychological treatments by making more positions available for clinical

psychologists:

There needs to be many more positions available to six year

trained Psychologists in Community Health Centres and public mental health services

so that consumers can access these services. Psychological therapy positions

should not be down graded into generic mental health worker positions or to

other professions with short training in a limited number of psychological

therapy skills.[487]

6.32

Better access to psychologists was not only supported

for its potential to increase the scope of mental health services but also for

helping to provide a better balance between 'drug-therapy' and 'talk therapy'.

Some submissions expressed a view that medication as a treatment was sometimes

overused by both psychiatrists and GPs, and that non-pharmacological treatment

was often effective as an alternative or in combination with medication. The Western

Australia Section of the College of Clinical

Psychologists – APS - submitted that:

Research from overseas indicates that most consumers with less

serious mental health problems do not receive adequate care for their mental

health problems from GPs and this can lead to a worsening of their mental

health problems. Research also indicates that GPs tend to prescribe medication

for less serious mental health problems which adds to the high cost of medical care,

yet these individuals could be treated as effectively (and sometimes more

effectively) by psychological interventions provided by clinical psychologists.[488]

6.33

Beyondblue argued:

Non-pharmacological treatments, such as cognitive behaviour therapy,

are effective and therefore need to be more accessible to the general community

through improved access to psychologists and allied health.[489]

6.34

Access to psychological services was perhaps the single

biggest issue about which the committee heard evidence. In the private sector,

many psychologists registered to practise offer a range of psychological

treatment for mental health problems. However, as many submissions pointed out,

access to these private-sector services was beyond the financial reach of many.

The cost of a one hour sessions with a psychologist usually ranges from $100 to

$175[490] for which there is no

Medicare rebate, unlike consultations with private GPs and psychiatrists. The Mental

Health Association of NSW pointed out that 'people with

depression often want a choice between medication and counselling, but find

that their only access to counselling is through private practitioners, and

Medicare does not cover these services'.[491]

The Public Health Association of Australia commented that:

...for most people with mental disorders, clinical psychologists

in private practice are only accessible to those with the ability to pay. This

is therefore a greatly under-utilised resource, particularly as many of the

newer psychological treatments are provided by this group of mental health

professionals.[492]

6.35

This issue of whether or not governments should fund or

subsidise access to psychological treatment in the private sector, either

through Medicare or in some other way, was a recurrent theme of the inquiry. This

matter is discussed in more detail in a later section of this chapter.

6.36

The committee notes that private health insurance (ancillaries

cover) can provide some reimbursement of costs for psychological services, but the

benefits paid cover only a small portion of the cost paid for the service[493] and many people needing mental

health services are socially and financially disadvantaged, and cannot afford

private health insurance.[494]

General

practitioners

6.37

GPs are the first point of professional contact for a

great majority of people seeking help with mental health problems.[495] Although

research suggests that only 38 per cent of those with mental health problems

seek help, of those that do, 75 per cent do so in the first instance from

a GP.[496] Many with chronic physical

conditions visiting GPs frequently also have comorbid mental health conditions

such as depression and anxiety.[497] The

role of GPs in mental health is especially significant in rural and remote

areas, where there are often no other health workers.[498]

6.38

Dr Rob Walters of the Australian Divisions of General

Practice (ADGP) told the committee that 'it is general practice and not the

specialist mental health system that delivers the greater majority of mental

health care in this country', with over 10 million general practice visits in

2003-04 related to mental health.[499] Most

people with high prevalence disorders such as depression and anxiety are seen

by GPs.

6.39

The role of GPs as a 'gateway' to other services was

mentioned in a number of submissions.[500]

The AMA submitted that:

General Practitioners (GPs) are the most accessible medical

resource in the community and are the gatekeepers to other community resources

such as specialist psychiatric care and acute care.[501]

6.40

The ACPM argued that, because of the limited access to

psychiatrists and psychologists, GPs were significant providers of mental health

care, especially to the financially disadvantaged:

General practitioners ... have to provide a large proportion of

mental health services in this country. It cannot be overemphasised that the

mental health services general practitioners provide are to the most

financially needy, those who cannot access the private sector, and those with

the most difficult diagnoses in terms of their social impact – those with

chronic as opposed to acute problems who therefore cannot access the

crisis-focussed public system either.[502]

6.41

GPs should not be regarded as the last resort in

service provision. The AMA argued:

[It is necessary to] Recognise that GPs will not be able to

‘pick up the pieces’ when other mental health services, public specialist

mental health services in particular, are not able to provide sufficient

services to their consumers, particularly those with supposedly less serious mental

illnesses and those in extreme disadvantage, including financial disadvantage.[503]

6.42

In recognition of the reliance on GPs for the provision

of primary mental health care, the Australian Government in 2001 introduced and

funded the Better Outcomes in Mental Health

Care initiative (Better Outcomes). Better Outcomes provided education and

training for GPs in mental health, improved access to psychiatrist support for

GPs, and funded referrals to psychological services in private practice. Evidence

to the inquiry indicates that Better Outcomes has been a useful initiative,

though take-up by GPs and caps have limited its distribution. Better Outcomes is discussed in more detail

later in this chapter.

6.43

The Inquiry into the Human Rights of People with Mental

Illness in 1993 (the Burdekin Inquiry) had found that the training of GPs in

mental health was inadequate, and that they often failed to identify mental

illness.[504] The inquiry recommended

that GPs receive more comprehensive mental health education.[505] One of the results of Better

Outcomes has been an improvement in the mental health care skills amongst the

approximately 20 per cent of GPs who have undertaken

training. Several submissions argued that curricula at the undergraduate level

and in GP registrar training were deficient in mental health assessment skills

and care.[506] The ADGP suggested that the

training provided in Better Outcomes should be incorporated into GP registrar

training.[507]

6.44

It was argued that the general practice fee structure

for Medicare rebates discouraged the long consultations often required when

dealing with patients with mental health problems.[508] The Royal

Australian College

of General Practitioners (RACGP) submitted that more effective and

comprehensive care was achieved within longer consultations, yet the GP

consultation item structure encourages shorter consultations.[509] Evidence from the ACPM indicated

that a GP dealing with usual medical problems could normally see four or more

patients in the same time that they could consult with one patient with a

mental health problem.[510]

Other

professional groups

6.45

Social workers and occupational therapists are often

members of community mental health teams, performing case-worker and other

roles. However, the committee received little evidence regarding these

professional groups. Training courses for a relatively new group – Aboriginal

mental health workers – is addressed in Chapter 16 in discussion of the needs

of Indigenous people.

6.46

A submission from Psychotherapy and Counselling

Federation of Australia (PACFA) argued that the counsellors and

psychotherapists they represented (different from psychologists) were

under-utilised in the mental health field:[511]

Counsellors and psychotherapists are unique within the mental

health field with respect to undertaking in-depth training, usually at a

post-graduate level, in counselling and psychotherapeutic theory and skills, as

well as their mandatory requirements for ongoing clinical supervision for the

duration of the therapist’s career.[512]

6.47

PACFA argued that PACFA-registered practitioners should

be granted the GST-exempt status applied to psychologists and GPs, and should be

included in Better Outcomes. Such inclusion, PACFA argued, would 'provide a

much needed addition to the severely stretched mental health system and provide

greater consumer choice, and better mental health outcomes.'[513]

6.48

There are also non-health professionals who, in the

course of their work regularly encounter people with mental health problems.

Teachers are often the first to identify mental health problems in young

people; police officers are often relied upon to transport people with mental

illness to hospital; government agency employees deal with people affected by

mental illness; and family members are usually integral in care arrangements.

6.49

The Burdekin Report in 1993 recommended mental health

training for a broad range of professionals in the community and Mental

Health First Aid training is now available, increasing

knowledge, reducing stigma, encouraging supportive responses and assisting with

early intervention and the ongoing support of people with mental illnesses.[514]

6.50

Professor Tony Jorm and Ms Betty Kitchener (the

originator of the Mental Health First Aid

course), put the case that the course has been proved to be effective, and

recommended Australian Government funding to support and train a national cohort

of instructors:

Once these are trained, the program can be self-supporting just

like conventional first aid courses. For example, to train 100 additional instructors

and to provide seeding support for them would cost around $400,000. These

instructors would then train people who are outside the mental health sector,

but have an increased probability of contact with mental health issues. These

groups include teachers, nurses, welfare workers and family carers.[515]

6.51

The committee supports the idea of training in mental

health for the wider community, and notes that Mental Health

First Aid training can not only assist professionals such as teachers and

police, but can also reduce stigma in the community, as a result of the greater

general awareness of mental health issues in the community that results. The committee

heard, for example, about the provision of mental health support training for

hairdressers in Horsham, Victoria[516] – an excellent example of a group

who talk to a lot people in their community and who could thus benefit from

mental health first aid knowledge.

Initiatives that can improve access to better mental health care

6.52

In recognition of the need to increase the mental

health skills of the existing GP workforce, and the need to improve access to mental

health and allied health professionals, a number of initiatives have been

developed in recent years. This section of the chapter looks at these

initiatives, and discusses their achievements as well as some criticisms that

have been levelled. In particular, this section examines the following

initiatives:

-

Better Outcomes in Mental Health;

-

Chronic Disease Management Medicare items; and

-

More Allied Health Services program.

Better Outcomes

in Mental Health

6.53

The stated aim of the Better Outcomes initiative was

'the achievement of better outcomes for people with mental health problems by:

providing GPs with training; introducing incentives to GPs for delivering

structured, quality care; and enabling access by GPs and consumers to allied

health professionals and psychiatrists.'[517]

The initiative has been funded by the Australian government since 2001-2002 and

has five related components:

-

education and training for general practitioners

to familiarise them with the initiative and to increase their mental health

care skills and knowledge;

-

3 Step Mental Health

Process which rewards best practice mental health care by general practitioners

by providing remuneration for assessment, care planning and review of consumers

with mental health problems;

-

increased remuneration to general practitioners

for the extra time they spend with mental health consumers providing focused

psychological strategies;

-

access to allied psychological services to

enable general practitioners registered with the initiative to access focused

psychological strategies for their consumers from allied health professionals;

and

-

access to psychiatrist support for GPs by

providing remuneration to psychiatrists who participate in case conferencing

with other health providers, and who provide mental health consumer management

advice via the GP Psych Support service.[518]

6.54

The training component involves two levels:

-

Level One skills based training in managing

mental health disorders in general practice (six hours of training), and

-

Level Two training in extending skills in

psychological treatment such as counselling and therapy (20 hours of training).

These psychological treatments are known as Focussed Psychological Strategies (FPS)

under the Better Outcomes, and include treatments which are evidence-based. That

is, there is evidence to prove their effectiveness. Specific psychological

treatments included are cognitive behaviour therapy, interpersonal therapy, and

psycho-social education.

6.55

Once trained and credentialed, a GP can deliver these

treatments as claimable items under the Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS). The specific

MBS item numbers allow greater remuneration for the longer time spent in

consultation, such as for consultations over 40 minutes that are used to

provide focussed psychological strategies.[519]

6.56

In the 3-step Mental Health

Process GPs make a patient assessment, devise a care plan, and review progress.

On completion, GPs are entitled to a Service Incentive Payment (SIP) of $150. The

GP Psych Support service operates nationally 'to provide all general

practitioners with telephone, facsimile and email access to quality consumer

management advice from psychiatrists, within a 24 hour timeframe, seven days a

week'.[520] Also under this component,

psychiatrists are remunerated for case conferencing with GPs.

6.57

The component of Better Outcomes which attracted the

most comment during the course of the inquiry was Access to Allied Health

Services, which allows GPs who have completed Level One training to refer a

patient to allied health professionals under arrangements whereby the out-of-pocket

cost to the patient is nil or is a small co-payment, usually less than $10. The

great majority of referrals have been to psychologists, although the eligible

professional groups include social workers, mental health nurses, and

occupational therapists.[521] Referrals

in the first instance are for six visits, with an additional six visits allowed

subject to a review by the GP.

6.58

The Australian Government funds the Access to Allied

Health Services through Divisions of General Practice around Australia,

who then make their own funding arrangements with allied health services. Most commonly

this is either by individual contract, or by direct employment.[522] In Round 1 of the pilot stage of the

program, 15 Divisions received funding for Access to Allied Health Services

projects. In 2005 over 100 of Australia's

118 Divisions took up the initiative and receive funding.[523]

6.59

Uptake by GPs in the three years since the program

began has, according to the ADGP, far exceeded initial predictions of GP

interest,[524] if not government

projections. Data indicates that 20 percent (one in five) GPs had completed

training and registered.[525]

6.60

The ADGP submitted that:

The allied health component has been a particular drawcard for

GPs who have found that better access to allied health support has resulted in

improved clinical outcomes for patients and improved management in the primary

care setting.[526]

Of all the measures funded by the federal government under

recent national mental health plans, Better Outcomes has been a relative policy

success, a success that has been consistently supported by all national mental

health stakeholders...[527]

6.61

Local evaluation reports compiled through ADGP showed

that participating GPs, allied health professionals and consumers were 'very

satisfied' with the evolution of services through Better Outcomes.[528] ADGP commented that the nation-wide

Divisions of Practice have been instrumental in driving reforms and encouraging

GPs to take up the initiative, and they have called for the capacity of the

Divisions Network to be expanded to improve the delivery of mental health care

to better meet community needs, including access to health care by key groups:[529]

The

network, which is already in place and funded, is a unique infrastructure and

agent of change that can build and support GP led sustainable primary mental

health care teams, support primary mental health care work force development,

promote coordinated and integrated care by linking general practice with other

systems, deliver quality primary mental health care services, deliver models of

service delivery tailored to local contexts and reach rural and regional

Australia.[530]

6.62

Concerns have been expressed about the limitations of

Better Outcomes, including:

-

Insufficient take-up by GPs;

-

Difficulties for rural GPs in undertaking Better

Outcomes training;

-

The need for GP practices to be accredited;

-

Adequacy of 20 hours training in psychological

treatment;

-

Lack of access to psychologists in rural and

remote areas;

-

Limits placed on the number of patients GPs can

treat and refer;

-

Conflict of interest in pharmaceutical companies

funding training; and

-

The need to remove disincentives for longer

consultations by GPs.

Insufficient

take-up by GPs

6.63

Despite the positive reaction by GPs, it is

nevertheless the case that only one in five GPs has undertaken

at least Level One training. Thus four in five GPs – often including those with

the least expertise in mental health - are not eligible to refer patients to a

psychologist under Better Outcomes.

6.64

It was suggested that the take-up so far was largely by

those GPs who already had an interest in mental health, and saw registering

with Better Outcomes as part of their continuing interest and professional

development and that GPs whose interests lay outside of mental health would be

unlikely to undertake the training. [531]

6.65

It certainly appears that the proportion of GPs

credentialed under Better Outcomes is unlikely to rise. The Department of

Health and Ageing indicated that 'the number of additional general

practitioners (GPs) who will complete Level One training under the Better

Outcomes in Mental Health Care Program is

about 150 each quarter and the number of GPs who will complete Level Two

training is about 50 per quarter'.[532]

While 600 GPs are completing Level One training each year, this seems no higher

than the annual rate of turnover in the profession. In 2004, 557 places were

filled in the General Practice Training Program,[533] and in addition to these new

entrants, some doctors are recruited directly into the system as general

practitioners from overseas. Thus the rate at which doctors are being credentialed

for Better Outcomes Level One is no greater than the rate at which new doctors

are entering the system, while the rate of training at Level Two may mean that

the proportion of doctors accessing this option will actually fall.

6.66

The paperwork in the 3-step process was cited as a

disincentive to take-up and, in particular, GPs were frustrated with the 'red

tape' and paperwork required to claim the Service Incentive Payment (SIP) of

$150. In recognition of these concerns, changes were made by the government in

May 2005, allowing the process to be completed in two consultations rather than

three. Nevertheless, take-up by GPs has been less than expected, resulting in a

reduction in the forward estimates for funds earmarked for SIPs of $85.4

million over four years.[534] The

Department of Health and Ageing told estimates hearings that in addition to the

revised 3-step process, other changes were being contemplated to try to improve

the take-up and make the process easier to use[535] and said in its submission to this

inquiry:

...more needs to be done, especially in terms of engaging more GPs

to use the components available in the Better Outcomes initiative. In

recognition of this the Australian Government has committed $228.5 million over

four years from 2005- 09 in supporting GPs in their role as primary carers of

people with mental illness.[536]

Difficulties for

rural GPs in undertaking Better Outcomes training

6.67

A further barrier to take-up by GPs according to some

submissions was the fact that it was difficult for GPs in rural and remote

areas to take time away from their practices to attend training, often

conducted in a city, as it could leave a town without any medical care. The

South Australian Divisions of General Practice submitted that:

The more remote Divisions report considerable difficulty

accessing the required training for their GPs to participate in the [Better

Outcomes] scheme... Training of GPs to do counselling themselves (Level 2 under

[Better Outcomes]) is likewise difficult as it requires the GP to do 20 hours

of training – not available in the country thereby necessitating the GP to

leave their practice unattended for a number of days. With the lack of

available locum coverage to backfill, and rural doctors required to provide

after-hours emergency care, this may leave entire towns and regions without any

medical care.[537]

6.68

The associated costs of travel, and of finding a locum,

were also a disincentive for rural GPs:

At present, there is no alternative for a rural or remotely

located GP but to travel to a regional or major centre in order to undertake

the entry point training for the Better Outcomes initiative (Level One or Two

accredited training). The travel requirements impose a significantly greater

burden on rural and remote GPs who often have difficulties finding and funding

a locum GP to service their area during their absence, and of course incur substantial

travel, accommodation and loss of income costs.[538]

6.69

The GPMHSC suggested that some accredited Level One

Better Outcomes training packages could be adapted for online or distance

delivery, but also recognised that face-to-face training was preferable. The

GPMHSC recommended that there be financial support provided for rural GPs

needing to travel to undertake training, and incentives for training providers

to deliver training in non metropolitan areas.[539]

The need for GP practices

to be accredited

6.70

Another barrier to GP take-up of Better Outcomes is the

requirement that for a GP to be eligible for the Service Incentive Payment, the

3-step mental health process consultations must be provided from a practice

participating in the Practice Improvement Program (PIP) or an accredited

practice.[540] The ACPM pointed out

that this requirement excludes qualified medical practitioners who for various reasons

do not see patients at an accredited practice – for example they may work at a

university medical centre. The requirement can also lead to anomalies:

[The requirement can result] in the absurd situation where some

practitioners are registered in one site and not in another. As an example the

College can cite a member ... who works in two accredited practices. In one, he

uses a room which is part of the accredited practice. In the other, the

consulting room which he rents is not physically part of the accredited practice

- it is in the same building but in a part designated as the Specialist Centre.

In that practice he cannot be registered for [Better Outcomes] despite doing

the same work and having the same qualifications (namely a Masters

degree in Psychological Medicine and additional qualifications) in each

setting![541]

6.71

The costs and resources associated with achieving

accredited status were also a barrier for some practices. Fundamental

reorganisation of practice structure could be necessary, which was a disincentive

for many.[542] The Northern Territory Government

said this was a particular issue for practices in the Northern

Territory:

While the Australian Government’s ‘Better Outcomes in Mental

Health Care’ initiative attempts to increase the capacity of

GPs to provide mental health care, the success of this initiative in rural and

remote areas of the NT has been marginal. Although a number of GP practices and

Aboriginal controlled health services in the NT were initially accredited and

accessed training, fewer practices are

now making that commitment due to the costs associated with achieving the

expected standards and the relative benefits for individual practices. The

uptake rate in the NT has been confined to a small group of Darwin

based GPs.[543]

6.72

The AMA and the ADGP pointed out that the practice

accreditation requirement excluded many Aboriginal Medical Services and

youth-specific services[544] yet these

were some of the highest need populations in the community.[545] The ADGP recommended exception criteria for GPs working outside

accredited practices, particularly those working with these high need groups.[546]

6.73

It was also pointed out that Better Outcomes

accreditation operates independently of other accreditation and professional

development for GPs. RACGP suggested:

At the moment the accreditation processes for mental health

training are separate from the RACGP quality assurance and continuing

professional development program. In the future it would make good sense to

roll these into one so that GPs do not have separate accreditation for mental

health and all their other areas of education. It makes sense to roll these

into the one QA and CPD program.

6.74

The committee agrees, and hopes that such streamlining

might encourage some more GPs to take up Better Outcomes accreditation.

Adequacy of 20

hours training in psychological treatment

6.75

A view strongly expressed to the committee was that the

20 hours of training comprising Level Two training was inadequate to equip GPs

with the necessary skills to provide effective psychological treatment (Level

Two training covers specific psychological treatments including cognitive

behaviour therapy). Organisations representing psychologists were adamant that

20 hours of training could not be considered the equivalent of the many years

of study and clinical supervision undertaken

by psychologists in order to register to practise. The APS submitted that:

The techniques that GPs are expected to master in 20 hours are components

of those required of psychologists to be registered to practise. Psychologist's

training for registration involves a four-year university degree in psychology,

two years post-graduate study (usually a Masters degree) and

at least one subsequent year of clinical supervision (at least six years

training). We believe that twenty hours of instruction in psychological therapy

techniques is not adequate training and does not meet appropriate professional

standards for mastering the skills for effective psychological intervention.[547]

6.76

The Association for Counselling Psychologists commented

that the 20-hour Level Two training for GPs has been seen by psychologists as

the equivalent of allowing psychologists to undertake brief training in

medicine in order to prescribe drugs,[548]

and argued that the delivery of psychological interventions should be reserved

to appropriately qualified licensed and experienced mental health specialists.[549]

6.77

There was some evidence that GPs were not necessarily

using the psychological treatment skills they had obtained under Level Two

training, but preferred to refer patients on to psychologists. Professor

Ian Hickie

told the committee that the training often had the effect of making a GP more

likely to refer on, rather than deliver the service him or herself:

What you see is that those GPs who have undertaken further

training actually make more referrals, not fewer referrals. There is a belief

system, which I think is quite wrong, that if GPs get more access to these

items themselves or further training they will not refer. All the research

evidence shows the opposite. The better trained people are, the more aware they

are of what they cannot do and the more aware they are of options and of what

others can do.[550]

6.78

At December 2004, almost 2000 GPs had referred almost

13 000 consumers for focussed psychological care by allied health

professionals, and almost 50 000 sessions of therapy had been received by

consumers.[551] GP-provided focussed

psychological strategies totalled over 33 500 for the period January 2003

to December 2004.[552]

6.79

A number of submissions commented that, with a shortage

of GPs in Australia,

it made sense to utilise the workforce of psychologists, rather than further

burden the already overstretched GP workforce.[553] Dr

Jillian Horton

commented that the long consultations required to deliver psychological treatments

were time-consuming for GPs, and encroached on their medical practice:

There is already a shortage of GP hours for medical care, and consumers

often complain about the difficulty in getting medical appointments. Why would

the Federal Government wish to burden this sector further and make the hours

for medical care even less available to the public, when there are clear

alternatives? Wouldn’t supporting a way to ease and re-direct the mental health

burden from GPs make more sense?[554]

6.80

Psychologists argued that the Medicare item numbers

used by GPs to deliver psychological treatments should also be available to

six-year trained psychologists:

Enabling psychologist access to the Medicare items for Focussed

Psychological Strategies ... would ease the mental health burden through

mobilisation of a significantly under-utilised trained psychology workforce.[555]

6.81

Whilst there appears to be general support across the

health professions for the idea of making better use of psychologists in the

provision of mental health care, there is some debate over how best to achieve

this, whether it should be through direct or indirect access to Medicare items

by psychologists, or through some other method. This matter is discussed

further in a later section of this chapter.

Lack of access to

psychologists in rural and remote areas

6.82

A number of submissions pointed out that although GPs

welcomed the Access to Allied Health, the program fell down when no suitable

professionals were available. This problem was most pronounced in rural and

remote areas.

6.83

The South Australian Divisions indicated that their

more remote Divisions had considerable difficulty in attracting appropriately qualified

and experienced personnel. [556] The ADGP observed:

...regional and rural Divisions face challenges such as

attracting suitably credentialed allied health workers to their communities.

This is often due to the availability of relatively short term (annual)

employment contracts. Recruitment and retention challenges are compounded by

Better Outcomes’ current status as a lapsing program which means it is

difficult for divisions to offer ongoing positions to allied health

professionals and facilitate recruiting and retaining them in rural and

regional centres.[557]

6.84

The South Australian Divisions suggested:

Some requirement or enticement for allied health workers to do

some rural service, either as a fly-in model, or for a limited period of time,

would also be welcome to address the workforce difficulties.[558]

Limits placed on

the number of patients GPs can treat and refer

6.85

The Better Outcomes framework imposes a cap on GPs and

their use of the Medicare items, presumably to control the budgetary

implications of the program. The cap limits GP's claims for individual services

(completed 3-step processes) to $10 000 per year per GP, which is the

equivalent of 67 mental health plans.[559]

6.86

Professor Hickie

argued that the cap discouraged GP practices from undertaking the practice

reorganisation needed to participate in the program:

The biggest disappointment from a GP point of view is what we

see as the cap on the number of services. The Commonwealth rejects this as an

issue, but what you want here is fundamental practice reorganisation, for GPs

to alter the way they work. In fact, if you say there will be a limit to the

number of people whom any individual or practice can service then you get a fundamental

disincentive. So there has not been the degree of GP practice reorganisation

that we would have hoped for...[560]

6.87

The government indicated that in 2004-05 only 17 GPs

out of over 4 000 who are trained had reached the cap.[561]

6.88

This was however not the only cap within Better

Outcomes that attracted criticism. Another cap limits the number of referrals

GPs can make under Access to Allied Health Services by limiting funding within individual

Divisions. The AMA submission expressed this concern:

[The] counselling component is subject to capped funding and GPs

are very limited in the numbers of services that they may refer patients to,

some Divisions reporting that they can only refer 5 patients per annum.[562]

6.89

The ADGP argued that allied health services are popular

with GPs, allied health providers and consumers, but that demand is far

outstripping supply. The ADGP called for an increase in funding for allied

health,[563] and pointed out the

inconsistency:

It is perverse that GPs belonging to Divisions who have worked

hard to enrol a large number of GPs in the program are then penalised when the

available allied health services are 'rationed' due to capped funds.[564]

Conflict of

interest in pharmaceutical companies funding training

6.90

The committee was told that pharmaceutical companies

are involved in funding for training in Focussed Psychological Strategies

(FPS). The appropriateness of this was questioned:[565]

The financial involvement of pharmaceutical companies in FPS

training is also a matter of serious concern. ... Such involvement represents a

grave conflict of interest that undermines the focus of FPS training.[566]

6.91

The concern originates in part from the tension that

currently exists between professional groups and their different approaches to

treatment, as well as an understandable concern about the motives of

pharmaceutical companies in funding training in non-pharmaceutical treatment

options.

The need to

remove disincentives for longer consultations by GPs

6.92

While Better Outcomes attempted to address the

financial disincentives to GPs for conducting the long consultations often

necessary when caring for people with mental health problems, the ACPM argued

that:

While the [Better Outcomes] item numbers redress [the

disincentive problem] to some extent their use is limited and not always

applicable...

The

College recommends that an extension of item numbers to recognise and reward

those performing more complex services should be introduced as a matter of

urgency. This should include item numbers for longer consultations, preferably

up to two hours in duration, as exist for psychiatrists and for ongoing

psychological care of patients with complex problems.[567]

6.93

The submission from bluevoices (the consumer body of beyondblue)

recommended a further increase in the rebate for longer consultations:

Beyondblue/blueVoices acknowledges the advances made in General Practice

in the Better Outcomes in Mental Health Care

Initiative, and recommends that in subsequent budget cycles, the level of

rebate offered to General Practitioners offering high quality mental health

services to consumers was increased even further. There must be a reduction in

the incentive to reward doctors for the number of patients they see each hour, when

it is widely accepted that the volume of patients seen does not equate to good

health care.[568]

Multidisciplinary

care planning, and Medicare items for chronic disease management

6.94

Historically, Medicare has only provided rebates for

services delivered by doctors.[569] In

recent years, however, the Australian Government has experimented (in a limited

way) with broadening the rebate to services delivered by allied health

professionals, such as psychologists, practice nurses, physiotherapists and

podiatrists.

6.95

Under Chronic Disease Management (CDM) Medicare items,

GPs can involve allied health professionals in the care planning of patients

with chronic and complex care needs, including patients with mental health

problems. The CDM items replaced (in July 2005) Medicare items for Enhanced

Primary Care (EPC). Medicare rebates are available for a maximum of five allied

health services per patient in a 12-month period, following referral from a GP.

Allied health professionals eligible include psychologists, Aboriginal health

workers, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and podiatrists. An allied

health professional must be registered with Medicare Australia

to provide Medicare rebateable services. The allowable five visits per 12-month

period can be to different allied health professionals, for example, two visits

to a physiotherapist, and three visits to a psychologist. The Medicare rebate

for any of these services is $44.85.

6.96

The Central Australian Aboriginal Congress, which

provides health services to Indigenous Australians in Alice Springs,

was positive about this initiative:

The advent of ... multidisciplinary care plans have also enabled

better coordination of team care arrangements for [patients with complex and

comorbid conditions], especially the coordination of GP involvement with the

necessary allied health professionals such as psychologists and other

counsellors who provide holistic care to these patients.[570]

6.97

The NSW Nurses' Association also welcomed the

initiative:

The introduction of the new allied health items under Medicare

is a great initiative which the Association supports and we look forward to

working with the Government to ensure that people with mental illness benefit

from greater access to skilled nursing interventions. We recommend that the

Government examine more closely the role of the mental health nurse

practitioner with a view to making the benefits and advantages of wider implementation

more widely available to the public.[571]

6.98

However, the Medicare items for CDM are limited to patients

with complex and chronic conditions. Further, although visits to allied health

professionals are subsided through Medicare, the level of rebate is just $44.85,

leaving a patient with high out-of-pocket costs after visiting, say, a

psychologist, whose session can cost $100 - $175 per hour.[572] Mr

Keith Wilson,

Chair of the Mental Health Council of

Australia, expressed this concern:

The recently introduced mechanisms under the chronic disease

management items ... cost a person up to an additional $50 or $60 out of pocket

to see a psychologist. You might get a $45 rebate, but it will cost you over

$100. ... I think that, worryingly, [this initiative] has still left a very

large burden of out-of-pocket expenses on those who wish to access [psychology]

services.[573]

6.99

For a person receiving care under a CDM care plan, the

$44.85 Medicare rebate applies regardless of the type or cost of service

provided. A session with a physiotherapist or podiatrist, for example, attracts

the same $44.85 rebate, despite the fact that these sessions may take less time

and cost less than that with a psychologist. The Department of Health and

Ageing indicated that:

[There has been] debate ... about the structure of the rebates

in relation to how services are provided for; for example, something like psychology

versus physiotherapy and the amount of time that is taken and the rebates which

are available. Where that structure might go in the future is a matter that is

being considered.[574]

6.100

Mr Wilson

indicated a preference for psychologists to be, in the main, contracted

directly and for out-of-pocket cost for consumers to be nil or very small:

[The Chronic Disease Management Medicare items arrangement] is

quite different to the system that the Council and most other professional

groups have championed under Better Outcomes, which essentially involved no

additional out-of-pocket expenses or a small co-payment.[575]

6.101

It is important to note that, unlike arrangements under

Better Outcomes, GPs do not require any particular training to make referrals

to psychologists under CDM arrangements.

6.102

Departmental officials advised that CDM items have been

funded by transfer of a projected underspend against, primarily, the Service

Incentive Payment (SIP):

There was, going back over the history of the mental health Service

Incentive Payments as part of the Better Outcomes program, an underspend

against what we had anticipated the level of expenditure to be, without the

capacity for particular precision in that process. Some of that projected

underspend going forward ... has been transferred to the [Medical Benefits

Scheme] to create the new chronic disease management items.[576]

6.103

Concern was expressed that this transfer shifted funds

from mental health to the more general area of chronic disease. In response, departmental

officials argued that chronic disease management comprised a strong element of

mental health, including in all the major chronic disease categories of cancer,

heart disease and strokes. Chief Medical Officer Professor John

Horvath told the committee that 'mental

health is ... an important component of the entire chronic disease spectrum'.[577]

More Allied

Health Services

6.104

The More Allied Health Services (MAHS) program aims to 'improve

the health of people living in rural areas through allied health care and local

linkages between allied health care and general practice'.[578] As with Better Outcomes, the federal

government funds Divisions of General Practice, which then administer and fund

allied health services. Unlike Better Outcomes, MAHS can fund a range of allied

health professionals, such as dieticians and audiologists, and not just mental

health professionals.

6.105

The MAHS program funds 66 Divisions - those with at

least five percent of their population living in rural areas - to provide

clinical care by allied health providers.[579]

Divisions can use direct employment by the Division, or engage allied health

service professionals under contract. The guidelines indicate that services

should be provided free of charge.[580]

6.106

The ADGP commented:

While MAHS was not a mental health initiative, a great

proportion of the eligible rural Divisions elected to devote it to the establishment

of allied psychological services in their community.[581]

6.107

In 2003-2004, the MAHS program engaged 45.7

psychologists, 23.2 mental health nurses, 8.6 counsellors and 12.5 aboriginal

mental health workers (full-time equivalents).[582] The Top End Division of General Practice

in the Northern Territory has

used MAHS funding to employ Aboriginal mental health workers.[583]

6.108

The Government guidelines for MAHS however discourage its

use where Better Outcomes is available:

If Divisions receive funding from multiple sources, they should

use this funding effectively. For example, a Division could seek to consolidate

their mental health services using Better Outcomes in Mental Health, leaving MAHS

for other allied health professionals.[584]

6.109

However, not all GPs are registered with Better

Outcomes and therefore cannot refer to psychologists. The Limestone Coast Division

in South Australia (covering an area around Mount Gambier) found MAHS to be an

important component of the mental health services available to GPs in that area[585] and MAHS, like CDM, allows GPs to

refer patients to psychologists or other mental allied health professionals,

without needing to have undertaken particular

training, as is the case with Better Outcomes.

What is the best model for increasing access to cost-supported

psychologists?

6.110

There was broad agreement that psychologists and other

allied mental health professionals play an important role in primary mental

health care, but that they are currently an under-utilised resource. Psychiatrist

Professor Ian Hickie

said:

...there is agreement across the whole medical and psychological

health work force. All we need is an integrated work force. We need people to

be working in partnership with each other, particularly at the primary care

level and at the specialist level. We are different in Australia,

in that we do not recognise psychologists as mental health specialists in the

way they are recognised in other systems, and we do not use them effectively.[586]

6.111

In the United Kingdom,

the National Health Service (NHS) funds psychological therapy services, and

patients can receive treatment on GP referral at no cost. Services are provided

at GP's surgeries, hospitals, or local community mental health teams.[587] The committee also notes reports

that the UK

system has waiting lists of nine months to access counsellors. Nevertheless,

there is significant recognition of the importance of psychological counselling

services.

6.112

Mental health teams in Australia often include

psychologists, but these staff are often have high work loads acting as case

managers for people with serious mental illness, and do not have the time to

provide psychological treatment, early intervention or relapse prevention

strategies. Dr Georgina Phillips commented that in her experience on a

community mental health team there were not enough counselling or therapy

services available, and that it was difficult to find affordable alternatives:

My experience was that we were constantly swamped with referrals

for young people who had long-term issues that needed long-term therapies and

we really struggled to appropriately refer them to something that was not going

to be quite financially difficult for that person.[588]

6.113

Affordable access remains limited and many submissions

supported expansion of the current Government initiatives. The following section

discusses the issues involved.

Should GPs need

particular training in order to refer patients to allied health professionals?

6.114

As previously discussed, GPs must have completed Level

One training and stay registered with Better Outcomes in order to refer

patients for low-cost psychological treatment through the Better Outcomes

program. This requirement seems inconsistent with the other Government

initiatives discussed above, which allow GPs to refer patients to cost-supported

mental health allied professionals without any additional training or

registration requirement.

6.115

More broadly, there also seems to be an inconsistency

in the fact that, in the case of referrals to medical specialists such as

cardiologists or psychiatrists, GPs do not require special additional

post-graduate training. Presumably this is based on recognition that GPs

receive enough basic training (in cardiology or psychiatry, say) in their

undergraduate degree or GP registrar training to equip them to recognise a need

for additional specialist care. It could be argued that the training received

at the undergraduate level in psychiatry and psychology should similarly allow

a GP to refer a patient to a psychologist, without a requirement for further

training. It would appear that arrangements under the CDM care plans and also

under the MAHS program already accept this proposition; yet a GP referring

under Better Outcomes needs additional training to make the same referral.

6.116

It was suggested to the committee that the Level One

training requirement (which allows a GP to refer to a cost-supported

psychologist) reflected the incentive nature of the Better Outcomes program,

which aimed to reward GPs for undertaking training and up-skilling.[589] However, a result of this limitation

on GPs is that patients are affected by their GP's willingness and ability to

undertake the Better Outcomes training. The training requirement precludes the

four out of five GPs who have not undertaken Better Outcomes training from

referring patients. The patients of these GPs are clearly disadvantaged by this

requirement.

6.117

Professor Harvey

Whiteford, Clinical Mental

Health Advisor to the Department of Health and Ageing,

acknowledged this as an issue:

You could take the position ... that the GPs who have less

interest in mental health—do not bother to do the training—should be the ones

who get better access to the psychologists who have the skills. I think the

view that has prevailed is that we want to encourage all GPs to upskill and the

quality of the referral to the psychologist is greater than the knowledge base

of the GP. ... I have sympathy with [the] view that the patients of GPs who are

not interested in mental health should in some way get support if they have

mental health problems. As Mr Davies

[Acting Departmental Secretary] said, there are some GPs who will not ever be

interested in mental health. It is not their area and they do not like it

particularly, but they may well have patients with those issues. I do not think

this strategy necessarily helps them as much as those GPs who are more

interested in mental health, so we needed to broaden the strategy as we work it

through.[590]

6.118

The question thus arises of whether it is sound and

reasonable to allow referral to cost-supported psychologists by all GPs. Professor Ian Hickie thought

that the medical profession would be willing to allow referral to

cost-supported psychologists by all

GPs, not just those who had undertaken particular training. The problem, Professor

Hickie suggested, was there not being

sufficient government funding to cover that increased degree of psychological

service and support.[591]

6.119

Professor Hickie

further suggested that allowing GP referrals to appropriately qualified and

recognised practising psychologists would quickly boost the mental health

workforce:

Fundamentally, this is an issue for the psychological profession

itself. But if those who agreed to reach a certain standard of training behaved

as mental health specialists, just the way that psychiatrists do, and then saw

people essentially on GP referral then I think you would have absolute

agreement between psychology and psychiatry.

...

If the Commonwealth were to immediately recognise the number of

psychologists who would automatically meet that [standard of training]—there is

some debate about that number but there would be somewhere around 2,000

psychologists—and they were to behave like the 2,000 psychiatrists we are working

in practice, we would immediately double the mental health specialist work

force, and it would not kill the Treasury.[592]

6.120

On the question of requiring a recognised system of

qualifications and registration for practising psychologists, the committee

notes that there is already government recognition of psychologists providing

services through the CDM care planning Medicare items. These psychologists must

be registered with Medicare Australia

for their services to be rebateable.

If a system of

referrals to cost-supported psychologists by ALL GPs is supported, should this

be done through a Better Outcomes-type arrangement, or through Medicare?

6.121

As mentioned earlier, GPs currently have the ability to

refer some patients for

Medicare-rebateable treatment by a psychologist (under CDM Medicare items). This

arrangement leaves patients with significant out-of-pocket costs, however, as

the rebate of $44.85 falls short of the cost of a session with a psychologist,

which usually exceeds $100. It is this concern about out-of-pocket costs which

causes the MHCA to favour a system such as Better Outcomes, where consumers

receive psychological treatment at no cost, or for a small co-payment.[593]

6.122

The APS supports an expansion of the arrangements under

Better Outcomes for Access to Allied Health Services, to allow more GP referral

for psychological services. At the same time, the Society also supports a

Medicare-based arrangement, allowing psychologists access to the same Medicare

item numbers for Focussed Psychological Strategies available to GPs who provide

this service after having completed Level Two Better Outcomes training.[594]

6.123

The issue of expanding access to allied health

professionals through Medicare has been raised in other forums. In 2003 the

Senate Select Committee on Medicare considered suggestions of extending

Medicare to cover allied health services, and acknowledged in its majority

report that such action would have considerable and complex economic and

financial consequences. A concern of that committee was that an extension of

Medicare would raise the issue of which services would receive priority for

Medicare funding and which would not qualify. It was also pointed out that

decisions about extending coverage could arbitrarily create a financial

windfall for certain professions while excluding others.[595]

6.124

The Select Committee on Medicare concluded that rather

than extending Medicare coverage, it would be preferable instead to utilise more

targeted and effective mechanisms to increase access to allied health

professionals. The committee suggested building on existing initiatives such as

the MAHS program, and providing funding for shared access to resources via

groups such as the Divisions of General Practice.[596]

6.125

The issue of extending Medicare coverage to allied