Chapter 4 - Resourcing

4.1

There is no doubt that more resources need to be

devoted to mental health services. Time and again the committee heard from

every stakeholder in mental health, from individual consumers to federal and

state governments, saying that more money needs to be spent on services.

4.2

This message is not new. It was clearly articulated in

the Burdekin Report of the early 1990s:

Lack of resources has bedevilled community-based care in much

the same way that inappropriately allocated resources contributed to the

ineptly executed demise of the large institutions. Clearly, resources and

effective coordination are imperative if mainstreaming is going to work.[181]

4.3

The committee heard that mainstreaming, despite the

rhetoric, has not been successful; that a 'silo' mentality continues to exist

within government departments, both state and federal; and that the integration

of services to provide resources where they are most needed has, to a large

extent, simply not occurred. It was suggested that nothing has changed since the

Burdekin Report and that the quote above is as relevant today as it was in

1993.[182]

4.4

Calls for greater resources certainly appear to have

been met with relatively little action. This is not to say, however, that

resources for mental health have been static for the last ten years. Funding

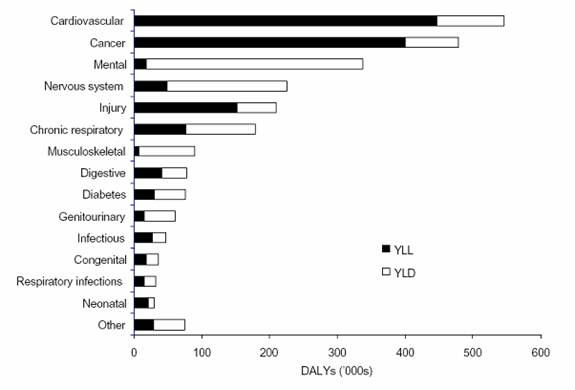

for mental health has increased steadily (Figure 4.1):

Figure 4.1 Growth in health expenditure and mental health expenditure.[183]

4.5

The graph shows that mental health expenditure rose by

about 65 per cent from 1992–93 to 2001–02. It also reveals the reason why resources

for mental health remain a prominent issue. Ten years ago, mental health was a

neglected field of health care. Since that time, expenditure on mental health

has risen no faster than health expenditure in general. This suggests that

mental health is not being given the priority it needs. Throughout this report

evidence is presented of capacity constraints and neglect across the sector

indicating that resource levels need to rise.

4.6

This chapter outlines the cost of mental health

problems, demonstrates the need for more resources, and outlines debate about

where those resources should go.

The Costs of Mental Illness

4.7

Mental illness costs the country a great deal in many

different ways. There are the human costs in terms of time lost to disability

or death, and the stresses that mental illnesses place upon consumers, carers,

and the community generally. There are financial costs to the economy which

results from the loss of productivity brought on by illness. Then there is the

expenditure by governments, health funds, and individuals associated with

combating mental illness and facilitating mental health.

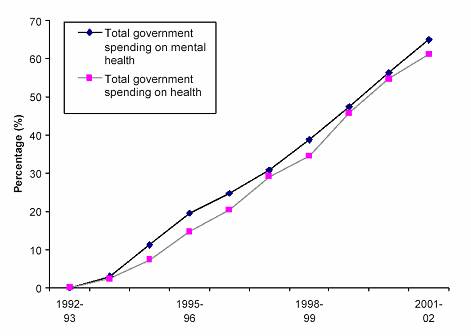

4.8

It is well established, but not well enough understood,

that mental illness is the number one health problem causing years lost to

disability (YLD) in the Australian community.[184]

Other diseases like heart disease and cancer may take more lives, but nothing

causes as much ongoing suffering and disablement as does mental illness. The

level of health burden caused by a disease can be measures in terms of

disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and Figure 4.2

compares these figures for major types of illness:

Figure 4.2 The burden of mental illness compared.[185]

4.9

Behind the figures showing the very high level of disability

due to mental illness lie two stories, one about health and one about human

suffering. In health terms, mental illnesses are different to most other

illnesses. The overwhelming burden of mental illnesses falls upon the young,

while most other conditions are more likely to affect the old. Thankfully most

mental illness is not fatal. However, the early onset of much mental illness

can mean that sufferers, particularly of acute conditions, can face varying

degrees of disability for many years of their lives. As shown below, this means

mental illnesses can create enormous costs for our health system and our

society – costs that are exacerbated if effective treatment and care are not

provided.

4.10

The human story behind the high level of disability

caused by mental illness is the story of considerable hardship faced by people

experiencing mental illness as well as those who care for them. These hardships

are documented throughout this report, but are borne particularly by the

families of, and other carers for, those experiencing mental illness, and this

is a focus of Chapter 11.

4.11

With so many people who experience mental illnesses

becoming ill at relatively early ages, it should be no surprise that these

conditions have major economic impacts. No comprehensive estimates are

available, but research on three conditions – depression, bipolar disorder and

schizophrenia – gives some indication of the issues. Beyondblue commented that the economic impact of depression was

large:

Apart from the social impact of depression, we know that over $3

billion is lost to our economy each year by not addressing the illness. These

costs are not just to the health sector but include indirect costs that impact

on other portfolio areas, for example welfare and disability support costs.[186]

4.12

SANE Australia

commissioned research on the costs of two particular mental illnesses. That

research showed for bipolar disorder:

The direct and indirect costs of bipolar disorder and associated

suicides are substantial. Real financial costs total $1.59 billion in 2003, 0.2

per cent of GDP and over $16,000 on average for each of nearly 100,000

Australians with the illness. Around half of this cost is borne by people with

the illness and their carers.

– Direct health system costs are estimated at $298 million in

2003, with two-thirds being hospital expenditure, 13 per cent medical

expenditure (GPs and specialists), 11 per cent residential care, 2 per cent

pharmaceuticals and the remainder on allied health, pathology, research and

administration.

– This represents only $3007 per person with bipolar disorder,

even less than spending on the average Australian’s health care and 0.43 per

cent of national health spending.

– 42 per cent of costs relate to depression, 36 per cent to

mania or hypomania and 22 per cent to prophylaxis.

– Real indirect costs are estimated at $833 million, including

$464 million of lost earnings from people unable to work due to the illness,

$145 million due to premature death (the net present value of the mortality

burden), $199 million of carer costs and $25 million of prison, police and

legal costs.

– Transfer payments are estimated at $224 million of lost tax

revenue (patients and carers) and $233 million in welfare and care payments,

primarily comprising disability support pensions.[187]

The results for an analysis of the economic impact of

schizophrenia reveal even larger costs:

The direct and indirect costs of schizophrenia and associated

suicides are enormous. Real financial costs of illness totalled $1.85 billion

in 2001, about 0.3 per cent of GDP and nearly $50 000 on average for each

of more than 37 000 Australians with the illness. Over one third of this

cost is borne by people with the illness and their carers.

– Direct health system costs were $661 million in 2001,

including 60 per cent hospital costs, 22 per cent community mental health

services, 6 per cent medical costs (GPs and specialists), 4 per cent nursing

homes and 2 per cent pharmaceuticals.

– This represents nearly $18 000 per person with

schizophrenia, over six times the spending on the average Australian’s health

care and 1.2 per cent of national health spending. Even so, it is clear that

public health spending in Australia

is at the low end of the international spectrum (1.2 per cent of health

spending compared to 1.6 per cent to 2.6 per cent in other comparable

countries)

– Real indirect costs were $722 million, including $488 million

of lost earnings from people unable to work due to the illness, $94 million due

to premature death (the net present value of the mortality burden), $88 million

of carer costs and $52 million of prison, police and legal costs.

– Transfer costs were $190 million of lost tax revenue (patients

and carers) and $274 million in welfare payments, primarily comprising

disability support pensions.[188]

4.13

As these studies have noted, a considerable proportion

of the economic costs of mental illness are borne by consumers and carers.

However, there is obviously also major government expenditure on mental

illness. For many years now, expenditure on mental health by governments and

private health funds has been outlined in the National Mental

Health Reports.

Expenditure on mental health

4.14

The different levels of government have different roles

in funding the mental health care system:

State and territory governments are primarily responsible for

the management and delivery of public specialised mental health services while

the Australian government, as well as providing leadership on mental health

issues of national significance, also subsidises the cost of primary mental

health services, principally through the Medicare and Pharmaceutical Benefits

Schemes. The Australian government also

subsidises private health insurance and directly funds a number of other

initiatives...[189]

4.15

Total expenditure on mental health services by federal,

state and territory governments and private health funds was $3.3 billion in

2002–03.[190] Detailed description of

historical trends and breakdowns of how the sector is resourced are covered by

the National Mental Health Reports, and are

not reproduced here. More detail is included in Appendix 2 to this report.

Mental health funding has risen in real terms, but it has risen no faster than

health funding generally.

4.16

In addition to this direct spending on mental health,

there is significant indirect expenditure by governments. Indirect expenditure

'refers to the estimated costs...of providing other social, support and income

security programs for people affected by mental illness'. The Commonwealth

indicated it spent $3,648.6 million across the following items:

-

Income support payments.

-

Workforce participation programs.

-

Department of Veterans' Affairs disability

compensation payments.

-

Housing and accommodation programs.

-

Aged care residential and community services.

-

Home and Community Care programs.

-

National Suicide Prevention Strategy (NSPS).[191]

4.17

Government expenditure due to mental illness is even

broader, however. As Chapter 13 will show, a significant number of people who

come into contact with the justice system, do so as a result of mental illness,

and this is an economic cost of caring for the mentally ill that is 'hidden' in

the budgets of state and territory correctional services authorities.

4.18

The private sector plays a significant role in mental

health care:

The private sector contribution towards hospital admission that

relate to MDC 19 Mental Disease and Disorders is substantial and it has

increased. In the last 12 months the proportion of all mental disease and

disorders treatments performed in the private sector increased by 5.7 per cent,

from 37.5 per cent to 43.2 per cent (2001-02 compared with 2002-03, Data source

AIHW).

The private sector provided 95,672 in-hospital treatments for

mental diseases and disorders in 2002-03. This included 73,137 same day

separations and 22,535 overnight admissions. ON average each overnight

admission had an average length of stay of 16.4 days. The private sector

provided 443,210 patient days in private hospitals.

In 2002-03 the private sector contributed at minimum $135

million toward the funding of in-hospital treatments for mental diseases and

disorders.[192]

4.19

There are many non-government organisations that

provide care and assistance for people experiencing mental illness. Some of

these do so under government funding arrangements. Many others, such as

Lifeline and GROW, do so largely on the basis of volunteer time, and donations.

Lifeline Australia

informed the committee that approximately 80 000 (or 27 per cent) of its

counselling calls in 2002 were known to be about mental health and that a study

conducted of Sydney

callers found that 69.5 percent of those callers suffered from high levels of

psychological distress.[193] Except in Victoria,

Lifeline does not receive any recurrent government funding 'to manage

increasing demand of mental callers'. It is interesting, however, that

government agencies refer clients to Lifeline, if they are in crisis.[194]

4.20

A great part of the cost of care of many people

experiencing mental illness is carried by their families and carers. Individual

carers on average contribute 104 hours per week caring, or being on call to

care, for people with mental illnesses.[195]

Without the sustained efforts of carers and family members, the current mental

health system would not function.

4.21

The costs to these families and carers are substantial.

As well as direct and indirect financial costs, families bear the social and

emotional costs of their family members' illnesses. Direct and indirect

financial costs borne by families include:

-

Ongoing expenses of health professionals,

medication and health programs;

-

Costs of travel whether public transport or

personal petrol costs of car & parking fees;

-

Replacing everyday items destroyed from loved

ones inability to use or care for items (saucepans; washing machines; vacuum

cleaners to personal items of clothing etc.);

-

Payment of abnormal expenditure and debts

incurred by loved ones;

-

Loss of incomes with the need to give 24-hour

care to loved ones;

-

Loss of housing opportunities, living with ageing

parents, substandard housing, homeless shelters; and

-

Loss of careers – carers and family members'

inability to fully commit to study and/or careers.[196]

4.22

Social and emotional costs include:

-

Significant health and psychological distress

experienced as a result of caring;

-

Breakdown in relationships due to the burden of

caring;

-

Reduced quality of life – handling the myriad of

issues from ongoing crises and/or relapses; and

-

Loss of self worth because of the stigma of

mental illness.[197]

4.23

Carers described the sacrifices they had made in their

own lives in order to carry out their caring role. One major impact of

providing ongoing care was the inability of carers to maintain full-time

employment. Having to give up jobs, or reduce working hours, not only affected

carers' financial wellbeing, but also their own sense of self and achievement.

I have had to leave my position as a senior social worker...after

20 years in ICU/CCU hospital settings...[198]

I was a very good teacher of maths and science, and, what is

more, enjoyed doing it very much – all my education and experience has been

lost to both myself, and the community, and my role as a carer has ensured that

I enjoy an old age of certain poverty – no superannuation for me![199]

4.24

For some families, lack of employment combined with the

additional costs of providing care leads to poverty.

We

just become poorer and poorer. I cannot get dental care; I’m on the waiting

list for that. You name it; I’m on the waiting list for a number of things

ranging from health care through to accommodation. I probably won’t be able to

keep the car going after this year. The payment I get is just not enough to live on. I can’t remember our

last holiday. I shop at St

Vinnies, haven’t had new

clothes for ages. It is just so tiring trying to make ends meet. It can come

down to, do I buy milk and food or go to the doctors.[200]

4.25

This wide range of sources of funding and support does

not hide two fundamental problems: not enough is spent on mental health

services; and it is not clear the resources are being applied wisely.

Not enough is spent on mental health

4.26

Just about every witness, whether government or

non-government, peak group or special interest group, health care professional

or consumer, indicated that the level of resources is inadequate.

4.27

The Mental Health

Council of Australia's (MHCA) first point about resources for mental health is

that there aren't enough:

The burden of mental illness and associated disability within

the community is not matched by the funding allocated to prevent, relieve and

rehabilitate people experiencing mental health illness.[201]

4.28

This message was explored in detail in their report Not for Service. The Australian Medical

Association (AMA), in response to the release of the MHCA report stated:

The 'Not for Service' report into Australia’s mental health care

system reveals a sad story of inactivity, poor planning, under-funding and

under-resourcing by all Australian governments in the face of one of the

biggest health challenges facing the nation in the 21st century – mental health

care.

At a time when demand for quality mental health services is at

its highest, our national commitment to the mental health sector is

frighteningly inadequate and fragmented.[202]

4.29

Other witnesses agreed including the Victorian Mental

Illness Awareness Council, the Mental Illness Fellowship Australia, and RANZCP:

the greatest impediment to policy implementing has been the

failure of government to provide adequate funding so that what is written as

policy actually can happen in practice.[203]

Federal government needs to lead states and territories in the

implementation of reforms and increase the funding allocation for mental health

and allied services. Australia

spends less than 7 per cent of the health budget on mental health. This sum

places Australia

well down on comparable amounts spent by OECD countries. Despite the low

funding allocated to mental health, it is the leading cause of disability.[204]

RANZCP believes that the mental health system in Australia

has all the right fundamentals but requires additional recurrent funding.

Ideally one billion dollars per year is required to reform existing mental

health service systems, ensure a sustainable workforce, address equity issues

and ensure the provision of an agreed level of service delivery in all

geographic areas.[205]

4.30

Medicines Australia

considered that 'More resources need to be devoted to treat mental illness,

given the disease burden placed on the Australian community'.[206] Beyondblue

broadly concurred:

One billion dollars is required as an injection for mental

health, with the Federal Health Minister taking on portfolio responsibility to

lead a reform agenda. The wider costs associated without a social coalition

approach cannot be underestimated.[207]

4.31

This need reflects widespread public perceptions,

reflected in the 70 letters sent as part of one write-in campaign to the

committee's inquiry,[208] as well as many

individual submissions by carers and consumers:

One of my adult daughters, who lives in NSW, has suffered from

schizophrenia for over ten years. During that time it has become more and more

apparent to me and other family members that there are many inadequacies and

gaps in the provision of adequate mental health care and community support

services for someone with her condition. I think that the majority of these

matters are a direct result of inadequate funds and resources being available

to mental health services.[209]

4.32

While there was a strong consensus on the general lack

of funding for mental health, there were also specific areas where that lack of

resources was perceived to create particular problems. The most prominent

concern was the lack of support for counselling, psychological services and

talk therapies:

Patient out-of-pocket costs are probably a key reason why few

people with depression or anxiety currently receive CBT, despite considerable

evidence for its cost effectiveness.[210]

4.33

Dr Gil

Anaf agreed, saying:

I am most interested to reverse an ill-informed push that aims

to reduce access to long term therapy services, and that aims to only promote

medication and quick-fix therapies as the main rebatable treatments.[211]

4.34

This position was also supported by the National

Association of Practising Psychiatrists, which indicated:

Psychiatrists are placed in an untenable ethical situation of

having to refuse appropriate treatment, where no other treatment would be

efficacious, because most patients do not fulfil the criteria of Item 319, and

because they cannot afford to treat more than one or two, or no, patients at

half the fee. Most patients cannot afford to pay half of the schedule fee if

they receive intensive treatment because many psychiatric patients are

vocationally and thereby financially disadvantaged. This legislation

contravenes the mandate of Medicare of equity of access.[212]

4.35

Psychologists Rudd and Jackson

agreed:

Cost of services is a major barrier for many in need, and not

just at the individual client level. For example, in Victoria,

it has been reported that teachers with special needs students (including

mental health difficulties) often find it difficult to access specialist

Psychologist services because of lack of funding.[213]

4.36

More generally, there was concern that the high level

of copayments was an issue, particularly for those without private health

insurance:

Co-payments are preventing people access to quality health

service. Without measures to reduce copayments, the Commonwealth Fund will continue

to document financial barriers to access for a significant percentage of

Australians. Those with mental illnesses will be amongst the most likely to

suffer.[214]

I can’t afford psychological counselling even with the $50

refund provided by my private health fund. My annual net medical expenses are

already about $7000. Medicare Plus also provides reimbursement of $50 for up to

five counselling sessions in a year but five sessions is not enough and it is

still expensive.[215]

4.37

The Australian

Council of Social Services (ACOSS) and others were concerned about equity of

access, citing as an example:

psychological counselling services, [which] are highly

restricted within the public system but available to those with sufficient

private means and/or private health insurance.[216]

4.38

Australian College

of Psychological Medicine noted:

Many sufferers from significant mental health disorders require

a multi-disciplinary approach, with the majority of them too socially

disadvantaged to afford private health insurance.[217]

4.39

BlueVoices reported a consumer saying 'I cannot afford

private health insurance so my only option for treatment is medication'.[218] This seems a recurrent and

disturbing complaint. BlueVoices also indicated that:

many consumers report to us that unless they have private health

insurance they are unable to afford the recommended fee of the Australian

Psychological Society for cognitive behaviour therapy from a Registered

Psychologist.[219]

Inappropriate targeting of spending on mental health

4.40

While the dominant theme in the inquiry was the

inadequacy of spending on mental health, issues were also raised around how

that spending was being prioritised and administered. A question repeatedly

raised about the allocation of funding for mental health, is why mental health

does not receive a greater proportion of the health budget:

In Australia,

the provision of mental health services receives an inappropriately low

priority having regard to the large number of people affected, the high burden

of disability, the untoward impact on service-deprived sub-groups within the

community and the missed potential for the cost-effective achievement of better

health outcomes. International comparisons of mental health spending are dated

(circa 1993) but suggest a spending shortfall in Australia

compared to Canada,

the US and the Netherlands.

A decade or so after the deinstitutionalisation of mental health, it is now

obvious that governments did not ensure enough resources for the new

community-based care structures to operate effectively.[220]

...

The Sane Mental Health Report 2004; 'Dare to Care' states that

Australia

spends less than 8 per cent of its national Health Budget on mental

health. The same report asserts that

comparable OECD countries spend upward of 12 per cent of their health budget on

mental health.[221]

...

While total health funding has grown over the life of the

National Mental Health Strategy, spending on

mental health has remained static in comparison with overall health spending;

yet mental health has grown as a component of the overall health burden.[222]

4.41

Another recurrent theme was the contrast between the

mechanisms for Commonwealth funds allocation and those of the states and

territories. Victoria

argued:

The Commonwealth funded health care system also constrains and

provides barriers to improving services to people with serious mental illness.

For example, newer atypical pharmaceuticals used to treat psychosis are not

always funded by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme so the states must find

this funding. Additionally, the Medicare Scheme does not impose significant

restrictions on the number of visits to private psychiatrists. Neither are

there adequate controls over the distribution of private psychiatrists, nor on

priority of access for those people most in need. Few incentives exist for

psychiatrists to take on new clients or to work in a public sector with capped

funding and more complex clients...

4.42

The South Australian Government described the problems

of coordinating services 'when enhancement monies from the Australian Government

may promote particular or specific aspects of a service only'.[223] The Queensland Government noted the

difficulties faced by the states and territories in 'invest[ing] new monies

each year on a recurrent basis, representing real growth in monetary terms',

which results in them having to 'fully fund reform'.[224] The Victorian Government argued:

More weight should be given to the constraints the states and

territories operate under that impact on the rate and extent of change. These

constraints include capped budgets and high levels of non-discretionary

expenditure related to meeting statutory obligations to involuntary clients.[225]

4.43

There was particular concern about the direction of

funds to medication and away from other therapies. Over the nine-year period of

the mental health strategy:

the Australian Government’s contribution increased 127 per cent,

though 66 per cent of this increase was accounted for simply by the increase in

expenditure on medications through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. While

new medications play an important role in improving mental health outcomes, to

achieve value for money they need to be backed by complementary psychological,

social, informational and self-management strategies. To date, significant

developments in these other areas have been promising but limited in scope or

reach (Hickie et al. 2004) and now require more overt long-term support by the

Australian Government.[226]

Psychotherapy (such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) has proved

to be a cost effective treatment for some mental disorders, especially anxiety

and depression. However, under the current Medicare arrangements, Medicare only

funds psychotherapy costs where the provider is either a psychiatrist or a

general practitioner with some welcome, but limited provision, for psychology

services through new initiatives such as Better outcomes in Mental

Health. This effectively restricts longer term psychotherapy

access to those people who either have ancillary private health insurance (for

a psychologist only) or can afford to pay the costs themselves, or to seek

treatment from a psychiatrist or general practitioner, or public mental health

services.[227]

4.44

The Western Australian Government also commented on the

true basis for the increase in expenditure on mental health by the Australian Government

since 1993:

When this increase (65 per cent in real terms) is further

examined it is found that in constant prices the major area of growth is in

Pharmaceuticals provided under the PBS. The increase in expenditure for

psychiatric drugs is nearly 600 per cent during this time period and accounts

for nearly two thirds of all the growth in Federal mental health expenditure.[228]

4.45

Other concerns have also been raised about the

allocation of resources, including that research on mental illness is

under-resourced:

At present, Australia

spends 3 per cent of funding on mental health research, compared to 9 per cent

for cancer research. The 8.9 per cent of NHMRC funds spent on mental health is

small when compared to the 19.1 per cent contribution of mental disorders to

disease burden in Australia.

Compared to other OECD countries, Australia

spends relatively little on research.[229]

4.46

The Commonwealth was critical of the argument that

money should be allocated directly according to percentage of disease burden.

Pointing out that costs of treatment vary from illness to illness, Mr

Davies of the Department of Health and

Ageing said:

to argue that the spending should be proportionate to the burden

of disease is not a safe line of argument to pursue, because obviously the costs

of treating different types of conditions vary. Just because something is 10

per cent of our burden of disease, to argue we should spend 10 per cent of our

health budget on it is not really a logical line of argument.

CHAIR—What is the argument? What is the line of establishing

what the level of spending is for particular burdens of disease?

Mr Davies—Spending

in health care and the allocation of resources between different conditions is

essentially a social, political, societal decision. In terms of the services we

fund, as the Australian government, all that Medicare spending, the PBS

spending, is ultimately determined by people’s propensity to seek out services

and doctors’ propensity to prescribe. There is no cap on the total MBS or PBS

budget, nor is there an allocation of that as between mental health and other

services. It is very much demand driven for the Australian government funding.[230]

4.47

The committee formed a clear impression that while Mr

Davies may be correct, the prevailing

'social, political, societal' view is that resources for mental health are

deficient.

4.48

Consumer groups are concerned about whether consumers

have an adequate role within the funded health care system:

Consumer self advocacy groups, organisations and individuals

have insufficient funding to provide the overwhelming support needs of

consumers whose rights have been abused. Nor do we have funding to provide the

kinds of alternative supports that we know will work for many of us. Nor do we

have funding to allow us to hold forums, conferences, communicate with each

other. Without funding we remain voiceless and disconnected. Without funding we

cannot participate in any of the ways that our mental health policies tell us

we should be participating.[231]

4.49

It was also argued that funds provided to advocacy

groups have not been targeted appropriately:

Current funding to consumer groups hosted and controlled by

groups such as MHCA and ‘beyondblue’ is a misuse of these limited funds and

needs to be redirected to genuine consumer-survivor organisations.[232]

4.50

Non-government organisations (NGO) are an integral

component of the mental healthcare workforce, providing much-needed services to

the community that are either not available – or in short supply – through the

public or private systems. Federal, state and territory funding to NGOs,

particularly funding allocated on a recurrent basis, is severely limited,

reducing the ability of NGOs to provide an optimal level of service. NGOs

reported that the shortage of funding has resulted in having to turn away

people who are in need of help. These matters are examined in Chapter 9. Instead of funding NGOs, including

consumer-run organisations, the vast majority of resources continue to be

channelled to the public and private for-profit organisations.

The problem of the pilot

4.51

As the committee travelled across Australia,

it kept hearing about promising pilot schemes, project trials and new program

proposals that were not receiving funding support. There were recurrent

complaints that pilots were not rolled out to a broader public, regardless of

their success; that projects were not placed on a sustainable budget basis; and

that groups applying for grants could not effectively plan for the future of

their operations.

4.52

The MHCA submitted:

Australia

is often known as “the land of pilots”, and with good reason. The mental health sector is littered with

project and pilots that are funded for a short period and then abandoned.[233]

4.53

The NT Mental Health

Coalition submitted that:

... over the past few years the federal government has funded some very innovative and effective

'pilot projects'. However, the lack of ongoing funding for these projects from

either the federal or NT governments has resulted in the loss of good services

and clients having expectations being raised only to be disappointed.[234]

4.54

St Luke's

Anglicare Limited, which offers Psychiatric Disability Rehabilitation and

Support programs stated:

Our agency has been able to provide some pilot recovery programs

for young people who experience psychosis but we have no recurrent funding to

support these early intervention recovery and rehabilitation programs in the

longer term. Philanthropic sources of funding are very limited for this group

of consumers.[235]

They recommended that recurrent funding be provided for such

services so that target programs for young adults could be offered.[236]

4.55

The SA Divisions of Private Practice also raised

concerns about the current practice of providing short-term funds for pilot

programs:

... Divisions of General Practice have a history of episodic,

short-term project, and pilot funding by government. This is also evident in other parts of the

health system, especially for work that seeks to bring about system

change. By the time one project nears

completion, the funding agenda has moved on and hence the opportunity to

capitalise on the learnings and apply them more broadly is lost. SADI recently had the experience of a

successful pilot project which aimed to re-align private psychiatrist practice.

... This project was terminated by the Commonwealth Government Department of

Health and Ageing at the completion of the pilot phase ... The termination

occurred before the planned (and paid for) evaluation had been completed or

submitted. No evidence was provided as

to why this decision was made. It was

clearly not based on objective analysis of the comparative evaluation

data. Short term episodic funding often

makes the whole system worse, as clinicians, consumers and carers become

cynical. ... Pilot projects need to be a part of an overall strategy, and if they

show benefit, need to be rolled out more broadly.[237]

4.56

Concern about insecure funding and a preponderance of

pilot projects was shared by other groups.[238]

The committee heard about a dieting disorder pilot program that was neither

continued nor expanded, despite no evidence to suggest it had produced poor

results.[239] It heard about the lack

of recurrent funding to indigenous community-controlled health organisations

being linked to service delivery inefficiencies.[240] Similar stories were recounted by

many organisations, particularly those in the non-government sector involved in

advocacy, support and service delivery.

4.57

MHCA identified a number of difficulties for

organisations and programs that receive short-term funding, including that:

consumers, their carers and families become distressed, with adverse effects on

their mental health, when a successful program is cancelled; uncertainty

regarding tenure acts as a barrier to recruiting and retaining quality staff;

organisations suffer a loss of corporate knowledge; and organisations can be

prevented from engaging in long-term planning.[241] The St. Vincent de Paul Society also

identified those difficulties for organisations and recommended a return to

recurrent funding to guarantee continuity of programs.[242]

What more is needed?

4.58

More funding is needed for mental health care, but

attention needs to be paid to more than just the amount. The committee heard

that other areas of concern are that mental health care be extended to more

people; that enhanced resourcing must go hand in hand with continuing reform;

that there be better integration of services; and there be more accountability

for and evaluation of mental health expenditure.

Greater resources

4.59

Witnesses made suggestions about how much extra funding

was needed. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists

(RANZCP) believes that:

... the mental health system in Australia

has all the right fundamentals but requires additional recurrent funding.

Ideally one billion dollars per year is required to reform existing mental

health service systems, ensure a sustainable workforce, address equity issues

and ensure the provision of an agreed level of service delivery in all

geographic areas.[243]

4.60

In an answer to a question from the committee about the

application of those funds, RANZCP responded as follows:

... the RANZCP seeks a level of funding for mental health care

commensurate with the burden of the disease. We provide below a breakdown of

the major targets for increased funding.

-

An additional $500 million a year is required for primary mental health

care, including access to allied health professionals, the Better Outcomes in

Mental Health Care Initiative, and reform of the Medicare Benefits Schedule

rebate for psychiatrists to encourage better delivery of consultancy services.

-

Youth mental health requires an additional $50 million per year.

-

Funding for mental health research should be increased from $15 million

to $50 million per year.

-

The remaining funding we envisage would be spent on the following

components, although these components are not all individually costed.

-

Employment participation, including:

-

Specialised schemes for people on a Disability Support Pension to

resume work;

-

Trials of workplace mental health awareness, screening and

implementation programs.

-

Population measures (such as destigmatisation programs, community

education, prevention, and early intervention).

-

Assistance for consumers and carers.

-

Annual and independent reporting on progress in national mental health

reform ($300,000 per year).[244]

4.61

The RANZCP expected that the money would come from the

states and territories, as well as the Commonwealth and did not consider that

funds should be transferred from other areas of the health budget.[245]

4.62

As stated earlier Medicines Australia recommended a

similar increase in funding, as did the MHCA:

Increase expenditure on mental health by $1.1 billion per year

over the next ten years, refocus funding on the full spectrum of service

provision system and adjust existing funding mechanisms to bring them into line

with the new funding (not the other way around as is more usual).[246]

4.63

The MHCA also submitted that the recommended increased

funding should be applied differently from current funding:

We submit that, while significantly more funds are needed to

deliver acceptable mental health care, on their own they will not fix the

problems, merely deliver the same sort of services more widely. The Strategy

has got the broad policy right but continuation of its present approach will

waste money and lives. What is needed is:

-

leadership,

-

accountability,

-

governance, and

-

investment in research and innovation.[247]

4.64

ORYGEN provide specialised mental health services for

youth aged 12-25 years, and have advocated a roll out of their services to

youths nationwide. This involves the establishment

of 30 new services units across Australia

to serve an equivalent number of young people as is currently occurring through

ORYGEN's Victoria-based model. It is estimated that eight specialised mental

health services for youth would be required in NSW, seven in Victoria,

five in Queensland, three each in

Western Australia and South

Australia, two in Tasmania

and one each in the Northern Territory

and Australian Capital Territory.

4.65

ORYGEN have estimated the annual operating costs for each service at $17.5 million, with a total recurrent

cost of $525 million per annum.[248] Some of these costs would be offset by the

re-distribution of existing resources within Child Adolescent Mental Health Services and Adult Mental Health Services. However, capital costs would also

be required to establish the new services.[249]

4.66

ACOSS expressed concern about where extra resources

should go:

Calls for major increases in the mental health budget must be

weighed carefully against other options, which may help lower the incidence and

severity of mental illness and its impact at the individual and community

level.[250]

More coverage

4.67

Only approximately 40 per cent of people with mental

health disorders access professional help. As the MHCA asked:

What other health sector would accept a non-response rate of 62

per cent in any 12 month period.[251]

4.68

Families, carers and community groups are left to deal

with the majority of untreated cases. Yet:

Nobody suggest that we restrict funding for osteoarthritis so

that we only treat half the sufferers and require the community groups to

provide exercise and weight loss programs to the remainder. Nor do people suggest we restrict the supply

of statins to reduce cholesterol levels to half the people with high cholesterol

and require community groups to encourage lifestyle modifications for the

remainder of people at risk of cardiovascular disease. Why do we accept low

coverage levels and inadequate treatment for people with mental disorder? It is

one of the enduring puzzles that is not unique to Australia.[252]

4.69

Professor Gavin

Andrews argued that the necessity for

greater funding is not to improve existing care, but to meet this significant

unmet need:

We do not need additional funds to provide care to the 40 per

cent of the people currently consulting, we just need good management to ensure

that the appropriate care is supplied in the least restrictive

environment. We will need to double the

funds if we are to double the proportion of people in need who are seeking care,

to the level of people with physical disorders who seek care. I cannot think of any justification for the

under-treatment of people with mental disorders.[253]

4.70

There are thus at least two drivers of increasing

expenditure: the need for better services; and the need to serve more

people.

More reform

4.71

As Chapters 8 and 9 will reveal, the transition from

the old psychiatric institutions to mainstream hospitals and community-based

care is incomplete, and some believe it is a reform agenda that has stalled.

One of the key consequences of the slowness of reforms is that funds fail to be

freed up for new initiatives and high priority needs. Failure to close

stand-alone institutions, a phenomenon most marked in NSW and South

Australia, creates budget pressures that prevent the

transformation of the mental health care system.[254] This is because without the

closures, savings are not available to be reallocated to other services. This

is consistent with the experience of reform in Italy,

in which the closure of institutions helped force the development of effective

community care.[255]

4.72

While the closure of institutions may have forced

Australian governments to develop community care, this can hardly be said to be

adequate. Anglicare Tasmania

quoted from a study of the effects that the closure of institutions has had on

homelessness, in which it is suggested that authorities failed to recognise the

range of services that institutions provided, including the provision of

housing, and to fully cost and transfer those functions to community programs.[256]

4.73

Boystown identified a number of areas for reform:

Review costs associated with the delivery of integrated mental

health care. Special attention should be paid to decision making processes for

listing psychotropic medications under the Public Benefits Scheme and the

availability of comparable generic alternatives; access to bulk billing

services; and the criteria for accessing the Disability Support Pension.[257]

4.74

Many areas for further reform are discussed in more

detail in subsequent chapters of the report.

More integration

4.75

A more collaborative approach between all levels of

government is required to address the current 'crisis' in service delivery. The

Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Health and Ageing, the Hon

Christopher Pyne MP, outlined his view of the importance of addressing mental

health issues in the National Mental Health

Report 2004:

I...am aware that improving the mental health of the community

requires coordination across diverse areas of public policy, both within and

external to the health portfolio. Coordination

with action taken under the National Drug

Strategy and the National Suicide Prevention Strategy is especially critical,

but the need for linked initiatives extends to areas such as housing,

employment, social security, crime prevention and justice. Mental health can no longer be treated as an

isolated issue.[258]

4.76

The Parliamentary Secretary went further on a

subsequent occasion, saying that

Australia’s

states and territories stand condemned for their failure to deliver adequate

mental health services . . . perhaps it is time for them to cede their

responsibility for mental health to the Commonwealth.[259]

4.77

Professor Andrews

argued that these comments reflect concern both about the effects of

federalism, and the effects of poorly coordinated services:

Part of [Pyne's] rhetoric should be viewed in the light of

federal–state relationships. However, part does reflect the uncoordinated way

we fund our health systems — Medicare and Pharmaceutical Benefits at the

federal level, private health insurance, the state and territory provision of

public-sector services, and rising out-of-pocket expenses at the individual

level. A coordinated funding system would be preferable.

There are six contributors to Australia’s mental health service

— general practitioners, private psychiatrists, private psychologists, private

hospitals, state inpatient and community services, and non-government

charitable organisations. The work of these contributors is poorly coordinated.

It is like a six-horse chariot with six horsemen who seldom communicate.[260]

4.78

Others expressed similar concerns, complaining that

both governments and some individual agencies were 'passing the buck' for

providing better services:

There needs to be more resources as well as a better use of

existing resources and an acknowledgement that all Australian governments must

work together to provide adequate services for the mentally ill...

The statement by Christopher

Pyne, Australian Government Parliamentary

Secretary for Health: “Australia’s

States and Territories stand condemned for their failure to deliver adequate mental

health services” indicates a buck-passing mentality that is part of the

problem.[261]

A whole-of government

approach to mental health policy and funding should emerge from the

Commonwealth, in order to see the same level of integration in the States’

delivery of services. ...resources could be

better utilised if various silos of government were to develop more effective

collaborative arrangements...

The prerequisite to

achieving this is that the policy dialogue moves away from what have become

traditional notions of ‘core business’ beyond which an agency will accept no

responsibility, towards a ‘without prejudice’ discussion of those issues which

no single agency can hope to resolve and which are therefore ‘everybody’s

business’[262]

4.79

The patchwork of federal and state funding, coupled

with the provision of direct and indirect government funding to non-government

organisations, and a growing and changing role for the private sector, means

that integration, while vital, is a constant challenge.

4.80

The AMA was also critical of the way in which funds are

utilised within the mental health service sector:

Existing funding mechanisms favour defined episodes of care.

However the mental health conditions that generate the highest burden of

disease are chronic conditions and they require longitudinal care. The

Commonwealth/State funding arrangements are dysfunctional, funds are wasted in

duplication of administration and policy formulation while a silo mentality

detracts from the continuum of care.[263]

4.81

A consumer group said:

One of the biggest sticking

points for mental health services, including community non-government

organisations, is that the co-ordination of funding between commonwealth and

state governments via the CSDA agreement is an absolute bureaucratic nightmare,

full of gaps, centres more on “let’s try and short change this government or

that health service provider” than actually adequate[ly] funding in ‘real’

terms the ‘real’ costs of mental health service delivery that meets the needs

of people with a mental illness.[264]

4.82

RANZCP submitted that care must extend beyond mental

health care to all other relevant services needed by patients (general health

care, financial support, housing, substance abuse, rehabilitation etc.) and that

the development of a single integrated health system would require the removal

of structural barriers at state and Commonwealth levels, and substantial reform

in both sectors.[265]

4.83

RANZCP suggested the following strategies to achieve

better coordination:

-

the re-integration of drug and alcohol and dementia services with

mental health services;

-

inclusion of developmental disability services as an essential

component of the service matrix;

-

funding of nursing and allied health professionals in private

psychiatric outpatient practices such as More Allied Health Services (MAHS);

-

development of “stepped care” systems linking GPs and state mental

health services in the care of common and severe disorders, including

prioritisation of GP referrals over self-referrals in state services; and

-

encouragement of integrated staffing models, with more flexible

arrangements for public and private psychiatrists to work together will also

strengthen system effectiveness.[266]

More accountability and evaluation

4.84

As already outlined, funding for mental health is a

complex patchwork of direct and indirect expenditure, by different levels of

government, with spending based on numerous different policies, formulae and

guidelines. The National Mental health Strategy is meant to place the resourcing

of mental health in a coherent strategic framework, but it lacks a sharp focus

and was widely condemned for having few measurable performance benchmarks:

Unfortunately, what has been lost in this complex model of

funding and evaluation is effective service provision to the consumers, the

people at the heart of the issue. The National Mental Health

Strategy is not delivering mental health services effectively or efficiently

because it focuses on the process of managing funds and statutory relationships,

not on providing services to those people who desperately need them.[267]

4.85

The regular publication of National Mental

Health Reports provides a mechanism for accounting for

expenditure on and provision of mental health services at an aggregated level.

However, dollar figures and trends alone do not provide a complete picture on

whether expenditure has had any meaningful impact on service provision and

better mental health outcomes:

Whilst there have been eight National mental health reports

since 1994, there is still no accounting in them for the number of people that

are actually seen and treated in mental health services and whether they are

seen face-to-face, or merely by telephone contact. This contrasts with very specific details of

the number of Australians treated and even the number of hours spent treating

consumers by private psychiatrists in the private mental health sector. While

the private mental health sector has been collecting outcome measures of

consumers treated in private psychiatric hospitals over the last three years,

the public mental health system is only just starting to approach such a

project. There are also rumblings from

public sector clinicians that unless there is a very significant increase in

funding for such data collection, the outcome measurement process is likely to

further undermine the management of consumers in the public mental health

system.[268]

4.86

Additionally, it is not clear that the data that is

contained in the National Mental Health Reports findings necessarily reflect

the real position. The Australian Psychological Society (APS) submitted:

Although financial reports

support the conclusion that funding for mental health services has kept pace

with that provided to other areas of health, there is a strong sense from workers

in mental health facilities that positions have been lost, budgets reduced and

less and less services are able to be provided.

Repeated reports from APS members working in institutions or under

specific programs have raised concerns regarding this reduced level of funding

for mental health services by state and local instrumentalities. Although

these situations are clearly anecdotal, they are indicators of a crisis which

we believe currently exists in public mental health services.[269]

4.87

The MHCA also criticised the lack of accountability for

the provision of mental health services:

Over half of all public mental health services had not even

reviewed their performance against these standards [National Standards for

Mental Health Services] by June 2003, some seven years after they were agreed

to by all governments. This is a very clear example of the lack of

accountability and commitment to mental health by all Australian governments.

The reality of the reports of consumers, carers and providers is that they put

flesh on the difficulties of a system struggling to cope with the human cost of

the huge gap between policy and its implementation.[270]

4.88

The National Mental Health Centre submitted:

Crucial to addressing underlying impediments to realization of

these rights, such as disproportionately low mental health service funding and

priority from a whole-of-government perspective is the development of a

mechanism to ensure transparent service delivery and proper accountability of

mental health providers. Lack of accountability and secrecy systemically

undermine the legitimacy of complaints of people who have mental illness and

the confidence the community can have in the complaints systems and services

themselves.[271]

4.89

Part of the dysfunction of current funding arrangements

may well be attributable to the lack of discernable population health

monitoring. Professor Anthony

Jorm of the ORYGEN Research Centre advised:

It is amazing that we know so little about whether mental health

in Australia is

improving, worsening or stable. The only routinely collected indicator of

population mental health is the suicide rate.... We need to have other population

indicators which will monitor how we are doing as a nation and allow resources

to be focussed on sub-groups that are not doing well.[272]

4.90

Professor Jorm

further posits the question:

Why doesn’t Australia

already have population monitoring? The Australian Bureau of Statistics has

been collecting national data on mental health since the 1980s. However, they

have changed the measure they have used several times, making comparison over

time impossible. Even when a consistent measure has been used, other aspects of

the methodology have been changed. There is a need for consistent measures

collected at regular intervals using the same methodology.[273]

4.91

Catholic Health Australia

stated that governments should be aiming towards marked percentage improvements

in the health status and quality of life in the population generally and in

particular for vulnerable groups and recommended that:

Commonwealth and State/Territory Governments ... set targets for

improvements in mental health outcomes across the community and for specific

groups in greatest need and be held accountable for meeting these targets. [274]

4.92

The AMA suggested that the following themes should be

included in accountability mechanisms:

The importance of a proper econometric analysis of the need,

including the unmet need, for mental health services in Australia

with this analysis incorporated into future National Mental Health reports.

- The desirability of mandatory reporting by State

and Territory jurisdictions of the number of people treated and whether those

people are treated face-to-face or by telephone.

- The need for a significant increase in the

resources for outcome measurement in the public mental health system.[275]

4.93

It was widely argued that the establishment of a

national mental health commission would be a major step towards ensuring proper

accountability for mental health provision. A group of Australia's

most prominent mental health experts made a compelling case for the

establishment of an independent Mental Health

Commission to fill the role of anti-discrimination campaigner, information

repository and leader of coordinated mental health reform.[276] The authors cited the successful New

Zealand Commission as particularly suggestive for Australia,

but also referred to similar bodies in the United

States and the United

Kingdom.[277]

The New Zealand Commission has widespread powers encompassing:

-

human rights and anti discrimination agendas

without being restricted to these agendas (as would a commission set up under

the HREOC);

-

a formal mandate to monitor and identify service

gaps, oversee training and performance management and conduct evidence based

reviews and consultations;

-

an ability to provide continuity through

government change; and

-

the capacity to pursue a positive political

agenda, avoiding sequential and often unproductive inquiries.[278]

4.94

The model is distinctive in that the Commission is

established by legislation for a defined period, to perform specified tasks to

a set time frame, with the options of extensions until its work is assessed to

be completed:[279] 'ultimately, doing

itself out of a job becomes the measure of its success'.[280]

4.95

Particularly promising is the potential to override

federal, and state and territory tensions with their resulting 'buck passing'

and compartmentalisation of services. Despite concerns that the NZ Commission

would act as an unconstructive critic of Government, the NZ Ministry of Health,

Directorate of Mental Health, has found it has

been a most effective partner 'walking alongside us' in the reform process.[281]

4.96

Under the auspices of the New Zealand Commission,

mental health reform has replicated or adapted several Australian mental health

initiatives.[282] However, in New

Zealand these reforms were embedded after

wide consultation and appraisal of the international evidence base; service

gaps were then identified and resources accurately costed to fill these gaps.[283]

4.97

Many others were supportive of a commission. The Mental

Health Legal Centre, for example, submitted:

... the establishment of an adequately empowered and independent

national complaints and accountability mechanism may well be the only way to

address the serious deficiencies in terms of both 'civil libertarian' and service

access and quality rights which endure, Burdekin Report and National Mental

Health Strategy notwithstanding.[284]

4.98

The MHCA suggested:

That the Commonwealth Government establish regular, frequent and

formal reporting mechanisms to the Prime Minister and Heads of Governments on

specific key indicators including an annual public report to the Prime

minister, 'The State of our Mental

Health', with data which reflects user and carer experience, not just system

measuring indicators. Leadership of this process should be vested in an

independent, empowered national office or person with direct access to the

Prime Minister.

That the day-to-day responsibility for the National Mental

Health Strategy within the Commonwealth Government rests with the Cabinet level

Minister.[285]

4.99

The Centre for Psychiatric Nursing Research and

Practice and many others argued for a commission that would provide independent

monitoring and recommendations to guide performance of mental health services.[286]

Conclusion

4.100

This chapter has given a broad picture of how mental

health services are resourced, and a brief sample of the barrage of criticism

levelled at the system. It is not often that a committee hears such a united

chorus of criticism from such a diverse array of organisations and individuals,

and the concerns obviously raise serious questions about the adequacy of mental

health care in Australia.

4.101

Later chapters look in more depth at specific areas of

mental health care. First, however, the committee considered the diversity of

mental illnesses, and some of the fundamental assumptions that underpin their

treatment.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page