Chapter 2

Setting the scene

Scope

2.1

Given the wide scope of its terms of reference the committee has aimed,

in its first report, to provide a survey of the breadth of issues that have

been raised with it so far and to provide some direction for the focus of

future reports over the course of its inquiry to 2010.

Distribution and composition of the Indigenous population

Australia's Indigenous population

2.2

As noted in Chapter 1 this report uses the most widely accepted definition

of remoteness—the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+). After

the 2006 census, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimates the

Indigenous population of Australia as at 30 June 2006 to be 517 000 people, or 2.5 per cent of the total Australian population. In terms of absolute

numbers, New South Wales and Queensland have the highest number of Indigenous

residents, with 148 200 and 146 400 respectively. Western Australia has an

Indigenous population of 77 900 and the Northern Territory 66 600.[1]

2.3

The committee notes that although major cities are home to the largest

single proportion of Indigenous people, a comparatively higher proportion of

Indigenous people live in regional and remote areas of Australia. In 2006, an

estimated 43 per cent of the Indigenous population were living in regional

areas and an additional 25 per cent in remote areas,[2]

thus the scope of the committee's inquiry covers almost 70 per cent of the

Indigenous population.

Location of Indigenous communities

2.4

According to ABS data, in 2006 almost one-fifth, or 93 000 of Australia’s

estimated 517 000 Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders lived in a

discrete Indigenous community. The term 'discrete Indigenous community' refers

to a geographic location that is bounded by physical or legal boundaries, is

inhabited or intended to be inhabited predominantly by Indigenous people, and

with housing or infrastructure managed on a community basis.[3]

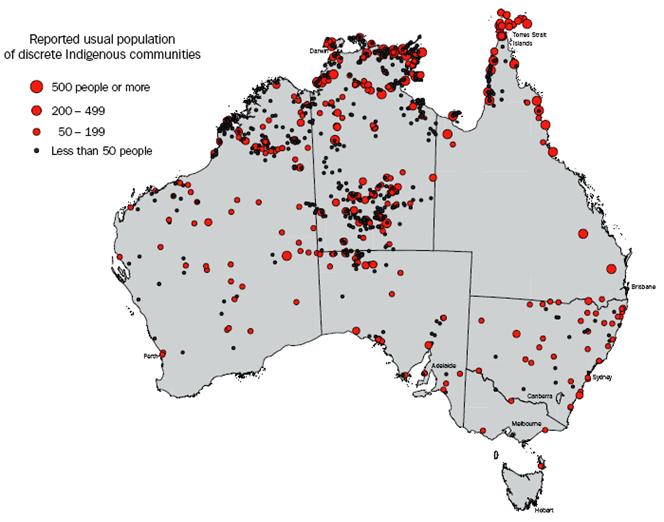

2.5

As can be seen from Figure 1 below, showing discrete Indigenous

communities by remoteness, the majority of discrete Indigenous communities,

approximately 85 per cent, are located in remote or very remote locations. The

remaining 15 per cent of discrete Indigenous communities are located in either major

cities or the inner/outer regional areas, in communities such as Redfern in Sydney

and Framlingham in western Victoria.[4]

Fig. 1 – Discrete Indigenous communities and

remoteness locations

|

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics,

Housing and Infrastructure in Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Communities, Australia, 2006 (Cat. 4710.0)

(ABS

data used with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistics) |

|

2.6

There is also a great diversity in the distribution of Indigenous

communities between the states and territories. The Northern Territory has the

highest proportion of Indigenous people living in discrete communities, approximately

45 per cent, with 81 per cent of its Indigenous population living in remote or

very remote areas. In Western Australia 15 per cent of Indigenous people live

in discrete communities with 41 per cent living in remote or very remote areas.

In contrast, in states like South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales

almost half of the Indigenous population live in major cities.[5]

2.7

John Taylor states:

Reference

to remote Australia draws attention to the vast two-thirds of the

continent where economic development and access to goods and services are

severely impeded by small numbers and long distances. Fully one-quarter of the Indigenous

population lives scattered across this landscape in places that are either

close to, or on, lands they have owned via descent or other kin-based

succession for millennia. Overall Indigenous people account for almost half of

the resident population of very remote Australia; although away from the main

service and mining towns dotted across this vast area, they are by far the

majority...this means that Indigenous people and their institutions predominate

over the bulk of the continental land mass.[6]

2.8

The committee notes that although the ABS data is the most comprehensive

statistical analysis of the Indigenous population, according to the Australian National

University's Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR), there has

been a substantial undercounting of the Indigenous population in the 2006

Census. CAEPR estimates this undercount to be around 11.5 per cent nationally,

but of greater interest to the committee is that the extent of the undercount

is most significant in Western Australia (with a projected 24 per cent

undercount) and the Northern Territory (with a projected undercount of 19 per

cent).[7]

Size of Indigenous communities

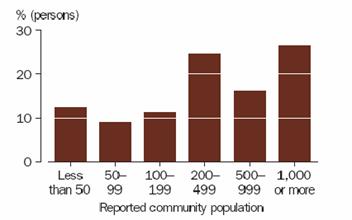

2.9

ABS data indicates that out of 1 187 discrete Indigenous communities a

total of 865 communities, or 73 per cent, reported a usual population of less

than 50. Of these 1 187 discrete remote communities 17 had a population of 1 000

or more.[8]

This is depicted over the page in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Population distribution and location by

size of community

|

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics,

Housing and Infrastructure in Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Communities, Australia, 2006 (Cat. 4710.0)

(ABS

data used with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistics) |

|

2.10

In 2006, 26 per cent of people in remote Indigenous communities lived in

one of the fourteen communities with 1 000 or more people such as Yuendumu in

the Northern Territory and Hope Vale in Queensland. A further 41 per cent of

people living in discrete Indigenous communities lived in communities with

between 200 and 1 000 residents and 20 per cent were in communities with

between 50 and 199 residents. Nearly 13 per cent of people lived in communities

with a population of less than 50 people.[9] See figure 3 over

the page.

Figure 3 – Population distribution, remote

communities, by size of community – 2006.

|

Source: 'Housing and

Services in Remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Communities', Australian Social Trends, 2008 (cat. 4102.0)

(ABS

data used with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistic)

|

|

2.11

The size and geographic location of Indigenous communities has an

obvious relevance for policy makers when contemplating service delivery to

Indigenous people in regional and remote communities. However there are other

factors that impact on service delivery and Indigenous community wellbeing. It

is well known that the Indigenous population is relatively youthful in

comparison to the non-Indigenous population. Research indicates that this is

due to a combination of higher fertility rates as well as higher mortality

rates. While much of the non-Indigenous Australian population contemplates how

to fund their retirement, many Indigenous people are unlikely to reach retirement

age. The needs and concerns of Indigenous people are therefore focused at the

other end of the social policy spectrum—on raising families, child health,

education, criminal justice, family housing, and jobs.[10]

2.12

Another factor relevant to regional and remote Indigenous communities is

the rate at which Indigenous people move between their home and other

communities. While on average Indigenous residential relocation rates are the

same as the rates for the non-Indigenous population, Indigenous people relocate

far more often in and around major cities but far less often in remote areas.

In remote areas Indigenous people are far more likely to move temporarily

between communities within a region, with high rates of travel within the

region for relatively short periods of time.[11]

Range of issues and emerging themes

2.13

As discussed in Chapter 1, the committee notes the breadth and depth of

issues raised with it both in submissions and during its inspection visit in

the Kimberley region of Western Australia. These issues are discussed in detail

under chapters 2-6 under each term of reference. While many of the issues are

complex and will require further consideration during the committee's inquiry

to 2010, the following themes have emerged during the inquiry process thus far:

- A perceived need for a greater investment in people, resources and

infrastructure to meet the needs and aspirations of regional and remote communities;

- A commitment from state and territory and Commonwealth

governments to long term relationships and partnerships with Indigenous people

and communities as way of solving entrenched problems;

- Ability of government programs to be tailored to the needs and

strengths of communities, not the other way around;

- Increased accountability of bureaucracies to Indigenous people

and communities; and

- A perceived lack of awareness of the serious nature of the issues

confronting people living in regional and remote Indigenous communities.

2.14

The committee considers that it has an important role in bringing these

issues to the attention of not only the Senate but also to increasing awareness

amongst the Australian public more generally.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page