Chapter 8 - Investment

Provisions of AUSFTA relating to investment

8.1

Chapter 11 of the AUSFTA sets out the obligations of

the parties in relation to investment.

8.2

In Australian public discourse, the term 'investment'

is often used in a somewhat narrow sense, to describe investment in financial

products or real property. In the

AUSFTA, however, 'investment' is given its technically accurate meaning, and

therefore includes almost any activity which involves the commitment of

resources in return for reward, with the acceptance of risk. The DFAT Guide to the Agreement offers a

series of examples of investments, including the following:

-

an enterprise, that is, virtually any form of

business for profit;

-

financial instruments including equity, debt,

and derivatives;

-

contracts for construction, management, or

revenue sharing;

-

and, most broadly, "other tangible or

intangible, movable or immovable property and related property rights, such as

leases, mortgages, liens and pledges."[595]

8.3

It can be seen from these provisions that the

investment provisions capture an extremely broad range of economic

activities. They are consequently

extremely important in the context of the agreement as a whole.

Requirements under AUSFTA

8.4

Under the AUSFTA, the Parties agree to provide

investors from the other Party either national treatment (that is, the same

treatment afforded to domestic investors) or most-favoured-nation treatment,

whichever is most advantageous to the investor.

It also contains a number of provisions designed to reduce sovereign and

other policy-related risks associated with investors from each Party investing

in the economy of the other Party.

8.5

Specifically, the Parties agree to:

-

provide national treatment or most-favoured

nation treatment to investors from the other Party (Articles 11.3 and 11.4)

-

provide the protection of law to investors and

investments, in a manner consistent with international law (Article 11.5);

-

provide investors and investments with

protection or restitution in the event that a civil or military emergency

requires the requisitioning or destruction of the investment in question

(Article 11.6);

-

refrain from nationalising or expropriating

investments from the other party, except in accordance with law, and with

appropriate compensation (Article 11.7);

-

allow the free transfer of funds connected to

covered investments from one Party to another (Article 11.8);

-

not to establish discretionary performance

requirements in relation to import or export content, local content, preference

for local inputs, transfer of intellectual property, or restrictions on sales

(Article 11.9);

-

refrain from requiring that senior managers or

board members be of a particular nationality (Article 11.10); and

-

reserve the capacity to implement policies which

may be otherwise prohibited under the agreement, but which are necessary for

environmental reasons (Article 11.11).

Reservations

8.6

Not all investment falls under the AUSFTA. Annex I and Annex II of the Agreement contain

reservations allowing Parties to maintain existing non-conforming measures. Both Australia

and the United States

have included measures relative to investment in Annexes I and II. Any matter not mentioned in Annex I or Annex

II is subject to the AUSFTA by default.

Such investments are referred to in the Agreement as 'covered

investments'.

8.7

Australia's

reservations include:

-

the preservation of current non-conforming

measures undertaken by State and Territory governments (Annex I- Australia 1);

-

retention of assessment by the Foreign

Investment Review Board, though with substantially increased financial value

thresholds (discussed below) (Annex I- Australia 2-5);

-

investment in urban land (Annex II- Australia

3);

-

additional support for indigenous involvement in

enterprises (Annex II- Australia 1);

-

measures relating to leases on airports (Annex

II- Australia 13);

-

preservation of export requirements in the

government IT outsourcing program (Annex I- Australia 8);

-

any measure with respect to primary education

(Annex II- Australia 10);

-

authorisation and levying of foreign fishing

vessels (Annex I- Australia 10);

-

wheat exports (Annex I- Australia 11);

-

foreign ownership and foreign director limits

for Telstra (Annex I- Australia 13);

-

foreign ownership and control of media companies

(Annex I- Australia 15-16);

-

votes of foreign shareholders for Board

positions on the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories board (Annex I- Australia

17); and

-

foreign interests in Qantas (Annex I- Australia

19-20).

8.8

The United States'

reservations include:

-

regulation of atomic energy for industrial purposes

(Annex I- United States 1);

-

regulation of leases relating to mining and

energy (Annex I- United States 4);

-

preferential treatment for minority groups

(Annex II- United States 4);

-

access to Overseas Private Investment

Corporation insurance and loan guarantees (Annex I- United States 5);

-

regulation of commercial aviation (Annex I-

United States 6-7);

-

securities exchange registration and initial

public offers (Annex I- United States 9);

-

ownership of broadcasting licenses (Annex I-

United States 10);

-

ownership of cable television facilities (Annex

II- United States 2); and

-

the preservation of current non-conforming

measures undertaken by States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (Annex

I- United States 12).

8.9

Submissions and evidence raised a number of issues of

concern in relation to Chapter 11 of the AUSFTA. These were foreshadowed briefly in the

Committee's interim report[596] and

will be discussed in greater detail below.

Overall impact on investment

8.10

The central concern is clearly to determine the impact

the AUSFTA will have on investment in Australia. On the one hand, the Agreement may encourage

additional investment in Australia

by United States

investors. On the other hand, it may

encourage Australians to invest in the United

States where previously they may have

invested at home. Inevitably, of course,

both of these situations will occur, and a great deal of energy has been spent

during public debates on the AUSFTA in recent months trying to anticipate what

the net effect on investment is likely to be.

8.11

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade cited

investment as one of the most significant benefits of the AUSFTA:

It is in the area of

investment that the gains from the Agreement will perhaps be most significant

over time. Already the United States supplies nearly thirty per cent of Australia’s foreign investment, more than any other

economy. Australia ranks 12th among destinations for US direct

investment abroad. The United States is the biggest destination- 43 per cent-

for Australia’s foreign direct investment (FDI), and Australia is the 10th largest foreign owner of US

assets.

The Agreement will

enhance Australia’s attractiveness as a destination for US investment as it puts in place legal

guarantees and other measures that provide greater certainty for investors. The

negotiation of the Agreement has already made Australia a greater focus of US investor and media attention, and this will

continue during the US domestic approval process and beyond.[597]

8.12

The official analysis of the AUSFTA by the United

States International Trade Commission does not attach the same significance to

the investment aspects of the Agreement, offering a more subdued assessment:

The FTA will add transparency to the investment regimes of the united

States and Australia,

but is not expected to generate significant amounts of new investment between

the two countries, as the investment environment in each is already

substantially open.[598]

8.13

These more subdued claims are also reflected in the

government's own Regulation Impact Statement:

Similarly, Australia's

commitments under the Agreement with regard to screening of foreign investment

is unlikely to have a major impact on US

investment in Australia?

[599]

8.14

Attempts to quantify, or to quantitatively verify these

alleged gains have given rise to significant debate and various alternative

analyses. The Department of Foreign

Affairs and Trade commissioned the Centre for International Economics to assess

the economic impact of the AUSFTA, which it did using the G-Cubed and Global Trade

Analysis Project (GTAP) models. With

respect to investment, the CIE made the following observation:

Lowering transaction costs, strengthening the security of the

investment framework and highlighting the openness of Australia's foreign

investment regime in non-sensitive sectors have the potential to reduce a

proportion of the risk-related cost of capital in Australia (which reflects

investor uncertainty and transaction costs).

It is therefore likely that, whatever the impact on actual investment

flows, the overall impact of the investment provisions in AUSFTA will be

positive.

A difficult question is

how positive is the result likely to be and how will the gains be distributed,

particularly in more illiquid segments of the market?[600]

8.15

The CIE endeavours to quantify this benefit by

indicating the likely fall in equity risk premiums on the implementation of the

FTA. The term "equity risk

premium" is a useful measure of the cost of capital. A reduction in the restrictions and risks

associated with investing in a particular economy leads to a reduction in the

risk premium, and therefore to less expensive access to capital for investee

enterprises. The CIE, in a process

outlined on p. 34 of its report, arrives at a conclusion that under the AUSFTA

the risk equity premium would fall by 5 basis points (or .05 percentage

points). It should be noted, though,

that their analysis delivered an outcome of 10 basis points, which the CIE then

halved in order to deliver a conservative result. It should also be noted that this figure does

not appear to emerge from either G-Cubed or GTAP, but rather from a 'pragmatic'[601] series of calculations outlined in

the report.

8.16

In a newspaper article in May 2004, Professor John

Quiggin made the following observation critical of the CIE finding:

- the CIE is right to focus on the equity premium. The difficulty is in the assumption that

capital market liberalisation will reduce the equity premium and will have no

offsetting adverse effects. The proposed

changes are tiny by comparison with the floating of the dollar, the associated

removal of exchange controls over the 1970s and 1980s and the associated

domestic liberalisation. Yet there is no

convincing evidence that these changes had any effect on the risk premium for

equity.[602]

8.17

In an assessment of the CIE findings for this

Committee, Dr Philippa Dee argued against the CIE's link between the AUSFTA

changes to Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) assessment of investments

(discussed further below) and the equity risk premium in Australia:

The equity risk premium is a concept that captures the effects

of events that happen ex post, after an investment is made, that reduce or

eliminate the expected returns on that investment. A negative ruling does not put at risk the

entire amount that would have been invested.

The potential investor still has their uninvested capital that they can

put elsewhere-

There is no doubt that events that affect a country's equity

risk premium can have a powerful effect on investment inflows, and hence on output

and consumption levels in a country- A key factor likely to account for

Australia's apparent equity risk premium is that we have a commodity-driven

currency, so that the repatriated value of an investment in Australian

manufacturing can be greatly affected 'after the event' by the price Australia

gets for its wheat or coal.[603]

8.18

If Professor Quiggin and Dr. Dee are correct, and the

AUSFTA does not result in a significant reduction of equity risk premiums in

Australia, this in turn is likely to result in a dramatic reduction in the

forecast economic benefits from the AUSFTA.

DFAT, however, rejects Dr. Dee's assessment of the impact of the changes

to FIRB review thresholds:

The CIE found substantial gains to Australia from the

liberalisation of FIRB restrictions under AUSFTA. These findings are rejected by Dr. Dee on the

ground that FIRB liberalisation will not reduce the risk premium on investment

in Australia. But there is evidence that

complying with its provisions is seen by investors as onerous. In addition, other provisions of AUSFTA will

improve the investment climate and create added certainty for investors. The CIE's modelling assumes a very small

reduction in the risk premium of only 5 basis points, and in sensitivity

analysis, this is reduced to 2 basis points.[604]

8.19

In evidence the Department of the Treasury was

reluctant to endorse the CIE's expectation of a 5 basis point reduction, but

noted that in its view the precise number was less important than the policy

message it signalled:

Investment in particular is a very difficult activity to model,

so the modellers have come up with something that is logically consistent and

fits with what we call mainstream theory, but we also need to keep in mind that

this is giving us an indication.[605]

Dynamic productivity gains and

economy-wide benefits

8.20

As the Committee noted in its interim report, the

impact of Chapter 11 of the AUSFTA on the overall economic outcomes for

Australia will depend substantially on the impact of dynamic productivity gains

(or losses) arising from the AUSFTA. The

CIE Report outlines the concept in the following terms:

It is widely accepted that trade liberalisation allows countries

to move resources to more valuable sectors of the economy and consequently

brings about allocative efficiency gains.

However, trade reform does more than simply shift resources. When trade barriers are reduced on an

industry, competition increases.

Increased competition can change the behaviour of firms in that

industry, encouraging businesses to use better technology and business

practices either through innovation or quicker adoption of new ideas. Improvements to efficiency due to improved

work practices (as opposed to resource re-allocation) are referred to as 'dynamic

productivity gains'.[606]

8.21

Following World Bank research, the CIE identifies four

sources of dynamic gains, two of which are relevant to investment. The CIE describes those two as follows:

-

Dynamic

investment- As tariffs are often imposed on investment goods, a reduction

in trade barriers on these goods can lead to an increase in the return to

capital and therefore a rise in real investment and productivity. Higher incomes from increased productivity

lead to higher savings anf thus further capital accumulation.

-

Endogenous

capital flows- There is significant empirical evidence that gains from

international capital mobility are quantitatively important. Foreign direct investment from abroad may

bring new and improved technologies that could flow into the domestic economy

and increase market productivity.[607]

8.22

Because of the multitude of factors which can influence

the dynamic productivity changes associated with a policy measure, and because

consideration of dynamic productivity changes is a relatively new science, such

gains are extremely difficult to quantify with any accuracy. The CIE has dealt with this difficulty by

developing, based on a series of empirical studies, assumptions about the

likely dynamic productivity gains in several economic sectors.[608]

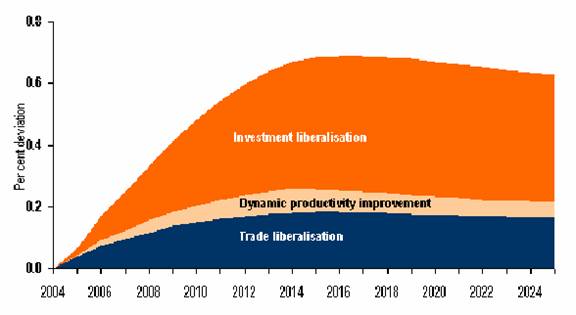

These productivity gains have then been used as inputs into the

calculation of the macroeconomic impacts of the AUSFTA on Australia. As can be seen below, the importance of

dynamic productivity gains in terms of overall gains in real GDP is

significant:

Figure 1- Changes in Real GDP[609]

8.23

The potential benefits arising from dynamic

productivity gains have underpinned much of DFAT's process of selling the

AUSFTA. The following extract from their

submission gives an indication of both the tone, and the significant extent to

which the outcomes of the AUSFTA rely on the forecast (direct and dynamic)

benefits from investment liberalisation:

According to the CIE's modelling, Australia's

annual GDP could be up by around $6 billion (about 0.7 per cent of GDP) as a

result of the AUSFTA a decade after the Agreement's entry into force. Total GDP

increase over 20 years is expected to amount to almost $60 billion in today's

dollars.

Much of this growth will be generated by the dynamic gains

expected from the deeper links the Agreement establishes between Australia and

the US, with the CIE finding investment liberalisation the biggest contributor

to the projected increase in Australia's GDP. But even if these benefits and

other 'dynamic' effects of trade liberalisation are excluded, liberalisation of

trade in goods and services alone would contribute about $1 billion to real

GDP.[610]

8.24

The CIE's assessment of dynamic productivity gains under

the AUSFTA has been criticised. In her

report for the Committee, Dr. Philippa Dee did not reject the consideration of

dynamic impacts altogether, but argued that a more conservative approach would

have discussed dynamic impacts without including them in the modelling:

The DFAT/CIE study draws on empirical work that shows that, in

addition to having so-called static effects on allocative efficiency, tariff

cuts can also have a so-called dynamic effect on sectoral productivity. The study quantifies these dynamics effects

by assuming them to be proportional to the size of their tariff cuts.

The studies that the DFAT/CIE study draws on examine

productivity levels in Australian manufacturing during a period of substantial

unilateral tariff cuts. AUSFTA does not

cut tariffs unilaterally, but preferentially- this means that the reductions

in price on any given import can be substantially less than the size of the

preferential tariff cut.-

The existence of such 'cold shower' effects of tariff cuts on

productivity has been hotly debated.

Conservative evaluations might note their possible existence, but do not

include them in the quantitative analysis.[611]

8.25

Dr Peter Brain of the National Institute of Economic

and Industry Research made a similar point:

In terms of a general

methodological issue or how the economic assessment should be made, the idea of

bottom line point estimates is absurd. I think we can all agree that whatever

the dynamic of flow-on effects will be, they will be large-whether it be a

multiplier of two, four, six or whatever-compared with the direct effects.

Therefore, the analysis should simply focus on the direct effects. This should

be done with some humility because there is a wide range of possible outcomes.

To accommodate this as best we can, one should try to take into account all

possible outcomes in a framework of decision making which allows an assessment

of the probable range of outcomes, which we have tried to do.[612]

8.26

Other evidence suggested that, even accepting the

inclusion of dynamic effects in the CIE model, the outcomes forecast are far

too optimistic. Professor Ross Garnaut,

for instance, stated:

The third element of gain is so-called dynamic effects which, if

you read the logic of the report, depend on the trade liberalisation being

genuinely liberalising. But if the trade liberalisation is not liberalising, if

it moves in another direction, then there is no reason to think the dynamic

gains will be positive. In fact it is very likely that if the trade

liberalisation effects are negative the dynamic defects will be negative as

well. So just on a straightforward application of the logic of the models-not

the words, and above all not the words of the executive summary, but the logic

of the models-suggests that the median estimate of gains would be approximately

zero. It would be possibly slightly negative but approximately zero, way below

the bottom end of the range of outcomes that CIE and DFAT suggested and put the

95 per cent probability bounds around.[613]

8.27

In other appearances before Senate Committees, officers

of the Treasury have been reticent about relying on dynamic effects as a basis

for policy decisions, instead adopting an approach more in line with that

suggested above by Dr. Brain and Dr. Dee.

During an appearance before the Senate Economics Legislation Committee's

inquiry into the International Tax Agreements Amendment Bill 2003, Mr Greg

Smith, Executive Director, Revenue Group, Department of the Treasury, made the

following statement in relation to a double taxation treaty:

The Treasury, perhaps

conservatively, but along with longstanding practice and what is also a common

practice in many countries-I will not say every country, but in most

countries-take the first-round effect and publish that. We draw attention to

the other effects-second-round effects, assumption driven effects or other

things which we are less certain about-but we have not incorporated them in the

official costing- We do a similar thing

really, when you think of it, with most of these sorts of things. For example,

we may well publish a costing for the research and development tax concession,

but of course the purpose of the research and development tax concession is to

create dynamic benefits in the Australian economy. We do not publish, and we do

not seek to estimate, in our costing what those benefits are.[614]

8.28

Treasury made similar statements directly in relation

to the FTA at an Estimates Committee hearing in October 2003:

The long term,

significant benefits from this agreement will come from the dynamic interrelationship

with the intangibles: competition policy; certainty; work programs on financial

services, which will be done through a financial services committee that is

being established between the two countries; and work programs on recognising

professional qualifications, which is one of the big impediments to service

trade at the moment. All of those things are very powerful but they are

impossible to quantify, so what you are left with when quantifying the model

are things that are easy to measure but perhaps not the most important part of

the agreement.[615]

8.29

DFAT, however, rejects criticism of the CIE's

assessments of dynamic productivity gains.

In a rebuttal of Dr. Dee's comments on this issue, DFAT stated:

Dr Dee rejects the idea

of including 'dynamic gains' which flow from the greater competition under

trade liberalisation because 'their existence has been hotly debated, and

conservative evaluations omit them.' But

there is a wealth of econometric evidence which supports the existence of these

effects. The CIE has been conservative in

its assumptions and has adjusted the magnitude of the gains to reflect the fact

that it is a bilateral agreement which has been negotiated.[616]

8.30

The Committee

is interested in DFAT's claim of 'econometric' evidence. If such evidence exists and is sufficiently

reliable to support this claim, why did the CIE rely instead on assumptions

based on empirical evidence?

8.31

It is clear to the Committee that the CIE's estimates

of the dynamic benefits of the AUSFTA should, at the very least, be treated

with a great deal of caution and scepticism.

Instead, the Committee should follow the approach recommended by Dr Dee

and Dr Brain, and indeed by Treasury in previous inquiries. The Committee recognises that dynamic effects

may result, and may have substantial benefits.

However, as Professor Garnaut points out, they may not. Policy decisions in relation to the FTA

should therefore be made principally on the basis of the direct effects, with

the recognition that dynamic effects may eventuate.

Changes to Foreign Investment

Review Board Thresholds

8.32

The Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) is a

statutory body whose principal function is "to examine proposals by foreign interests for acquisitions and new investment

projects in Australia and, against the background of the Government’s foreign

investment policy, to make recommendations to the Treasurer on those

proposals."[617]

8.33

Currently, FIRB reviews all proposals for

foreign investors obtaining substantial interests in Australian companies valued

in excess of $50 million, and all proposals by foreign interests to establish

new businesses in Australia valued at $10 million or more.[618]

If FIRB considers that such a proposal is not in Australia's national

interests, it may recommend that the Treasurer block the proposal.

8.34

As such, FIRB is clearly a non-conforming

measure under AUSFTA. For it to continue

in operation, appropriate provisions must be included in Annex I or Annex II of

the AUSFTA. Annex I includes provisions

which enable FIRB to continue to operate, but it lifts the thresholds. Under the AUSFTA, FIRB will only review the

acquisition of a substantial interest in companies valued in excess of $800

million.

8.35

The

Department of the Treasury has indicated that the new FIRB thresholds did not

emerge as a result of any perceived problems with FIRB from an Australian

perspective. Rather, the new thresholds

represented a compromise between the United States' wish to eliminate screening

and Australia's wish to retain it:

Ultimately, of course,

this was a negotiation, so there was a give and take, if you like. The US were, and remain, very strongly opposed to

screening in any form, and they see our arrangements as a potential restriction

on investment flows. From our point of view, we felt comfortable raising-and

the government’s judgment was that it was comfortable raising-it that far

because it achieved the balance between, if you like, the level at which

national interest concerns are likely to be real and tangible and, below that

level, the level at which they are not likely to be sufficient to warrant the

compliance costs associated with the screening.[619]

8.36

The

Government has also argued that the raised threshold is essentially a benign

change for two reasons. First, while the

reduced number of cases referred to FIRB would be substantial, "in terms of

value of investment-that is, not the number of transactions but the value of investment-under

the proposed arrangements with the US we will continue to screen over 70 per

cent of investment by value."[620]

8.37

Second,

Treasury pointed out that that FIRB has not been a barrier to US investment in

the past. Mr Chris Legg, from Treasury,

stated that "I do not think there have been many, if any, cases where US

investors have been rejected. There may have been one or two."[621]

8.38

A

number of submissions remained concerned about both of these issues. On the issue of the reduction in referrals to

FIRB, the Australian Council of Trade Unions noted:

The Office of US Trade

Representative estimates that 90% of US investment in Australia over the last

10 years would have escaped screening had the new rules applied

retrospectively. Using a three-year

retrospective time horizon, DFAT estimates in its Regulatory Impact Statement a

reduction in screened proposals by 65-70%.

Some commentators have claimed that, under the proposed AUSFTA rules,

around 86% of companies listed on the Australian Stock Exchange could be

acquired by US interests without being

screened.[622]

8.39

The

Australian Manufacturing Workers Union argued:

While the AMWU acknowledges

that the national interest test has rarely been invoked to prevent foreign

investment in Australia, the AMWU notes that the changes would mean that almost

99% of Australian manufacturing companies could be acquired under the proposed

AUSFTA with no regard for whether such an acquisition is in the best interests

of Australia or Australian workers. [623]

8.40

The

Federation of Australian Scientific and Technological Societies made a similar

point:

The second area of major concern in terms of allowing for the cherry

picking is the change in the threshold for FIRB, lifting its report threshold

from $50 million $800 million means that all R&D-intensive science and

technology SMEs would fall under that $800 million threshold and there will be

no examination. As you are aware, because of the ratchet mechanism, if a future

government decided it was concerned about an emerging trend of US

firms purchasing Australian R&D companies and taking them offshore, it

would not have the capacity to use FIRB as the instrument to address that

policy problem.[624]

8.41

In

relation to the argument that FIRB has not rejected incoming investments from

the United States, the ACTU made the point that:

We acknowledge that the

vast majority of applications that are screened by the Foreign Investment

Review Board are approved. However, the

Board also has a track record of approving applications subject to conditions

set to safeguard the national interest.

This aspect of the screening process should be borne in mind when it is

argued that the current process is simply a time-consuming one that leads to

approval anyway.[625]

8.42

It is

useful to also note the United States perspective on this issue, which confirms

that the increase in FIRB thresholds is likely to increase US investment in

Australia, but that the size of this increase will be muted by the relatively

open current arrangements:

US industry representatives

would also have preferred to discontinue the investment screening performed by Australia's FIRB.

However, the minimum size of most foreign investments that require

screening has been substantially raised. In general, U.S. investors in Australia must notify the Australian Government

(through the FIRB) of investments only if an investment is value at more than

A$800 million (US $443.2 million). The

previous investment threshold was A$50 million (US $27.7 million). Industry

representatives have stated that the higher limits are an improvement in the

investment approval process- Industry representatives indicate that due to

Australia's fairly liberal existing investment regime, they have been free to

invest in most industries despite FIRB screening, and that is not expected to

change.[626]

8.43

The

Committee notes that there is substantial evidence that the increased FIRB

thresholds will have little impact on US investors because the FIRB review

process is not currently a substantial barrier to US investment. However, despite this widespread evidence

that the impact is likely to be mild, the changes in FIRB arrangements are

considered by the CIE as a major factor underpinning the decrease in

Australia's equity risk premium (discussed above) and therefore as a major

factor underpinning the predicted benefits of the AUSFTA as a whole.

8.44

The CIE

report argues that "Australia

has relatively high [foreign direct investment] restrictions compared with

other countries in the OECD, surpassed only by Iceland, Canada, Turkey and

Mexico. These restrictions range from limits on foreign ownership in

certain sectors to modest screening procedures for a wide range of investment

proposals."[627]

8.45

Under

the AUSFTA Australia continues to maintain specific limits on foreign

investment in a range of sensitive areas such as newspapers, broadcasting,

Telstra, Qantas, airports, and urban land.

That is, Australia's 'relatively high foreign direct

investment restrictions' on sensitive sectors will not be reduced under the

AUSFTA. This leaves only the reductions

in the 'modest screening procedures' as the source of increased liberalisation

of foreign direct investment- and the impediment raised by this screening

process has been shown to be minimal. The AUSFTA will therefore do little to

reduce those core factors which result in Australia having 'relatively high foreign direct

investment restrictions'

8.46

It is

difficult to reconcile such a view with the view expressed above by the United

States International Trade Commission that Australia's investment environment is 'already

substantially open'.

8.47

Despite

all of this, and without any further explanation, the CIE argues that "we are still left with the fact that

Australia’s FDI rules are at the ‘restrictive end’ of the OECD scale"[628] and uses this as a justification for

assuming these restrictions are responsible for fully half of Australia's

current equity risk premium. This

provides the basis for a further series of calculations resulting in the claims

of a 5 basis point reduction in the equity risk premium under the AUSFTA.

8.48

The

Committee observes that the assumption that investment rules account for half

of Australia's equity risk premium is at best unproven, and may be

substantially exaggerated. Even if the

assumption is accurate, the AUSFTA appears (on the above analysis) unlikely to

reduce investment restrictions substantially.

In either case, there would be flow-on consequences which may reduce the

predicted benefits from the AUSFTA by billions of dollars.

8.49

Professor

Ross Garnaut criticised the CIE analysis of the impact of the changes to FIRB

in these terms, arguing that they failed what he described as the "laugh

test":

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has now released the

results of the consulting firm’s assessment of the agreement as negotiated.

While the main sources of gain in the original estimate resulting from access

to highly protected US agricultural markets have disappeared or shrunk

dramatically, somehow the total benefits have greatly increased to $5.6

billion. That somehow turns out to be mainly through what are described as back

of the envelope calculations of gains, hitherto overlooked from easing FIRB

restrictions. There is an air of unreality about this revised estimate. The

magnitude of the contribution now attributed to changes in FIRB rules and the

basis used to assess it heighten the need for an independent analysis conducted

at arm’s length from those whose job it is to sell the agreement to the

Australian community.[629]

8.50

In her

report for the Committee, Dr. Philippa Dee also took issue with the CIE

findings. She argued as follows:

- it is highly doubtful

that ex ante FIRB screening has any general effect at all on Australia's risk

premium- FIRM screening has an unknowable, but probably small, deterrent

effect on a few particular investments, but nothing like the number of

investments that would be affected by a generalised change in the risk premium.

8.51

The

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade continues to support the CIE's views:

In summary, the CIE found substantial gains to Australia from

the liberalisation of FIRB restrictions under AUSFTA. These findings are rejected by Dr Dee on the

grounds that FIRB liberalisation will not reduce the risk premium on investment

in Australia. But there is evidence from

investors that complying with its provisions imposes some costs. This reflects the fact that the existence of

a screening mechanism may reasonably be expected to have some impact on the

level of uncertainty for prospective investors and to contribute to their

general perception of risk, notwithstanding genuine efforts to implement the

policy in a way that minimises such effects.

In addition, other provisions of AUSFTA will improve the investment

climate and create added certainty for investors. The impact on the equity risk premium is

inherently difficult to quantify: however the sensitivity analysis does

indicate that the gains are significant even with a much smaller reduction than

assumed in the base case.[630]

Select Committee's view

8.52

The Select Committee, informed the weight of evidence

presented during the inquiry, is sceptical of the forecasts made by the CIE and

promulgated by DFAT during public debate on the Free Trade Agreement. The loudly proclaimed benefits to Australia

arising from a liberalised foreign investment regime and from dynamic

productivity gains are based on a series of inferences and educated guesses. The

fact that the US International Trade Commission states that the AUSFTA is 'not

expected to generate significant new investment' cannot be easily dismissed.

8.53

However accurate

the CIE and DFAT predictions may turn out to be, educated guesses do not

provide an adequate basis for informed policymaking by parliamentarians,

investors or citizens. The CIE report's

highly-contested views on investment and dynamic gains have inevitably led to a

debate played out in academia, in the media, and before this Committee. The result is that the modelling work which

was intended by the government to clarify the impact of the AUSFTA and justify

its adoption has in fact led to increased confusion.

8.54

Notwithstanding this, the Committee recognises that the

AUSFTA, by liberalising investment between Australia

and the United States,

is likely to provide a net benefit to Australia

in the investment arena. The Committee

is far from convinced that the benefit will be as great as that claimed by the

Government and the CIE, but it remains likely that a benefit will eventuate. Consequently the Committee does not oppose

Chapter 11 of the agreement, but its concurrence occurs despite, rather than

because of, the analysis undertaken by the CIE

and endorsed by DFAT.