Chapter 4

The effectiveness of the CPRS as an emissions trading scheme

4.1 This chapter sets out the findings of the Select

Committee in relation to the choice of the Government’s emissions trading

scheme as the central policy to reduce Australia’s carbon pollution taking into

account the need to:

-

reduce carbon pollution at the lowest economic cost,

-

put in place long-term incentives for investment in clean energy and

low-emission technology, and

-

contribute to a global solution to climate change

Coverage of the scheme

4.2

The CPRS will cover a range of greenhouse gas emission and sources.

4.3

There are six greenhouse gases listed under the Kyoto Protocol which

will be covered under the Scheme including carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous

oxide, sulphur hexafluoride, hydroflurocarbons and perflurocarbons.

4.4

Carbon pollution permits will be needed for all emissions covered by the

Scheme.

4.5

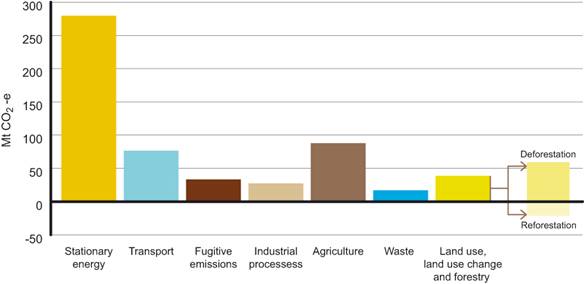

Chart 4.1 shows the contributions of various sectors to the 576 million

tonnes of CO2e emitted by Australian entities in 2006.[1]

4.6

It can be seen from the chart that the main cause of emissions in

Australia is stationary energy - notably coal‑burning power stations.

Chart 4.1: Australian emissions in 2006

Source: White Paper,

p. 6-3.

4.7

The CPRS is proposed to include 75 per cent of Australian emissions and

involve mandatory obligations for around 1,000 entities, considered to be the

largest emitters in the country.

The timing of the CPRS

4.8

The Committee notes that very few countries actually have emissions

trading schemes in place, namely, the European Union (where the scheme has been

roundly criticised for failing to deliver CO2

reduction outcomes) and New Zealand.

4.9

Therefore, central to the debate about whether Australia should

introduce the CPRS at this time, prior to Copenhagen, is the issue of should

Australia be leading the world, irrespective of actions the rest

of the world may or may not take.

4.10

The committee notes the Government's statement that 'climate change

requires a global response. In forging a global solution, Australia's actions

inside and outside international negotiations matter'.[2]

4.11

Originally the CPRS legislation had a commencement date of 1 July 2010.

4.12

In May 2009, the Prime Minister announced a 12 month delay to the

commencement date of the CPRS to 1 July 2011.

4.13

The Government stated that the later starting date is necessary 'to

allow the Australian economy more time to recover from the impacts of the

global recession'.[3]

United Nations Framework Convention

on Climate Change – Copenhagen Conference

4.14

In December 2009, the parties to the United Nations Framework

Convention on Climate Change will meet in Copenhagen to discuss a climate

pact to replace the Kyoto Protocol when it expires in 2012. The Copenhagen

meeting will include consideration of the trajectory of carbon emission cuts

through to 2020.

4.15

It is unclear at this stage whether developed nations will accept deeper

cuts than those they have pursued under the Kyoto Protocol for the period

2008–2012. It is also unclear whether key developed nations, notably the United

States, will take a legislated national position into the international

negotiations.[4]

4.16

Copenhagen will also discuss pledges for richer nations to increase

their budgets to pay for climate change adaptation and mitigation, and to

enable the transfer of affordable clean-energy technology to developing

nations. If progress is forthcoming on these issues of targets and funding, a

new pact may come into force on 1 January 2013. If the talks stall,

negotiations may stretch to 2010 and beyond.

4.17

The committee received conflicting evidence from witnesses as to whether

Australia should pass the CPRS before or after Copenhagen.

4.18

Some witnesses gave evidence that Australia has a responsibility to show

the way in international negotiations and that an early lead would resolve

business uncertainty. Others questioned the wisdom of legislating an Australian

emissions trading scheme before we understand what the rest of the world

intends to do to reduce carbon emissions.

Evidence supporting legislation before Copenhagen

4.19

Professor Ross Garnaut had been initially hesitant in supporting the

CPRS:

Senator IAN MACDONALD—...If it [the CPRS] were not modified..,

would it still be better than nothing?

Prof. Garnaut—That is a really hard question. Let me say it

would be finely balanced.[5]

4.20

After the Government's changes on 4 May, Professor Garnaut said:

When I was asked by Senator Macdonald and answered that it

was line ball, I said that there were three steps the government could take

that would make it substantially beneficial. The first of those measures was to

put back on the table the condition of 25 per cent reduction of emissions by

2020. The government has done that, so my assessment is that it now would be

clearly a positive for this bill to be passed into law.[6]

4.21

Professor Garnaut in his evidence noted that the diplomatic case for

taking a legislated cap and trade scheme to Copenhagen is the need for

Australia to restore credibility on the international stage following its

initial decision not to ratify the Kyoto Protocol.

4.22

His evidence to the committee included that the priority for Australia

at Copenhagen:

...is that we show that we are prepared to play a full

proportionate part in an ambitious global agreement. Australia, as the

developed country that would be most damaged by unmitigated climate change,

should be taking a lead in shaping that Copenhagen agreement towards an

ambitious outcome. If we had legislated the CPRS, that would just increase

confidence that we were able to deliver on what we were promising.[7]

4.23

He observed that:

The proposed legislation to establish an emissions trading

system has good elements. The best of them is that it establishes the framework

of an emissions trading scheme, the complex legal framework for many

institutions and instruments that would need to be part of an ETS. It has taken

much work and good work to get the legislation to this point. To now abandon

this legislation comprehensively would introduce the chance that no government

and parliament would want to try again.[8]

4.24

The Climate Institute also gave evidence that Australia has an important

role to play on climate change policy internationally:

What Australia does at home matters internationally. People

look at us very closely. I think it would be wrong to characterise Australia as

a non-player in the international talks. What we are doing here is being

closely watched in the United States in terms of the emissions trading design

and features that we have here.[9]

4.25

The Australian Industry Group (Ai Group) gave evidence that it would

support passing 'a better designed CPRS...with the right system.'

4.26

In evidence before the committee prior to the Government's 4 May

announcements, Dr Peter Burn of the Ai Group said:

Another way to put it is to say that even if we got no

greater indication of action at a global level than we currently have, but

we had a better designed CPRS [emphasis added], we would support that. We

are not saying wait until the rest of the world acts; we are saying let us act

now but let us do it with the right system [emphasis added]. That system

would be one that catered for the range of possible outcomes at Copenhagen,

gave strong protections for trade exposed businesses and that provided enough

time to get the design right and for business to prepare for the impacts.[10]

Evidence against legislation prior to Copenhagen

4.27

Other witnesses gave evidence of the potential disastrous impact on

Australia, including losing its competitive advantage, if it were to take

action prior to a global agreement.

4.28

Mr Mitch Hooke of the Minerals Council of Australia gave evidence

that:

...there are no prizes for unilateral action unless it is

effective, demonstrable leadership...The only counsel I would give anybody is: do

not overstate your own self-importance, do not get lost in the logic of your

own arguments and be prepared for a whole stack of movements and developments

the like of which you can rarely understand and appreciate.[11]

4.29

Mr Hooke also gave evidence that if Australia sets a carbon price

through the proposed CPRS in the absence of an international agreement,

Australian companies will be at a competitive disadvantage:

...Even if the Copenhagen meeting fails, Australian firms will

pay $8.5 billion in carbon costs every year from 1 July next year. None of

our competitors will confront such costs. The CPRS is not linked to the availability

of low-emission technologies. In fact, by imposing a $34 billion burden on

Australian businesses in the first four years, it will reduce, if not largely

eliminate, the ability of Australian firms to invest in these technologies. It

is completely out of step with other schemes being developed around the world. Australian

firms will pay the highest carbon costs of any other firms in the world. The

results will be lost Australian jobs, stalled investment and a less competitive

economy.[12]

4.30

Similar concerns were put forward by ERM Power.

4.31

Mr Trevor St Baker, Executive Chairman, ERM Power, gave evidence that to

ensure certainty for Australian business, the CPRS must be aligned in both form

and timing with an international agreement. As the process of an international

agreement may take years, Australia should concentrate in the interim on

investment in low emission and renewable technologies.

4.32

Mr St Baker said:

A prematurely legislated Australian CPRS would not deliver

certainty whilst ever there were a possibility that amendments might be

required to align our scheme with a global scheme. The process of designing the

scheme and the timing of such a scheme will start to be determined in

Copenhagen at the end of 2009 and will be decided by the major carbon

polluters, mainly the USA and EU, and of course in collaboration with China in

the longer term. That will not happen until sometime in 2010. The commencement

of a global scheme is unlikely prior to the end of the Kyoto scheme in 2013.

That is why, prior to the design and introduction of an international global

carbon pollution reduction scheme, Australia should concentrate on inducements

to investment in new, low-carbon emission power generation, including gas fired

generation, similarly to the inducements to investment in renewable generation.[13]

4.33

Dr Richard Denniss, Director of the Australia Institute, also gave

evidence against legislating prior to Copenhagen:

...why is Australia rushing in to have our CPRS legislation

passed before we have an international agreement at Copenhagen or beyond? A lot

of the uncertainty that we are talking about here is about what is possible,

what is going to be agreed to et cetera...One way to get around a lot of this

uncertainty about what the world will and will not agree to is to wait until

they do or do not agree to it.[14]

4.34

Dr Denniss raised concerns around the setting of targets prior to

Copenhagen and the potential negative impact of doing this ahead of an agreed

global target:

This parliament will be signing an open-ended, blank cheque

if we pass the CPRS with very low targets and then agree to more ambitious

targets at Copenhagen. Taxpayers will have to pick up the difference. We will

have to import an unknown quantity of permits from other countries, so we are

locking in very timid targets. We are about to go into an international

agreement where we do not know what will be the targets, and any shortfall will

be made up by taxpayers, of which I am one, so I have a vested interest. If we

are to have an emissions trading scheme that is designed to send strong price

signals to the people who are polluting I would rather wait to find out exactly

what will be our international obligation.[15]

4.35

Mr Andrew Canion, Senior Advisor, Industry Policy, Chamber of Commerce

and Industry of Western Australia, gave evidence that the view of the CCI is

that it is imperative that global action is taken. He said:

What we think matters is that Australian industry is

operating within the context of a global economy. It is important that we do

not have imposts on our industries that are not equivalent to imposts in other

nations.[16]

Committee view

4.36

The committee believes that action to mitigate the effects of climate

change requires a global response.

4.37

It is therefore imperative that Australia defer consideration of the

CPRS legislation until after an international agreement on greenhouse emissions

targets has been finalised.

4.38

Legislative action prior to Copenhagen will have a negative impact on Australia

and Australians. The committee does not support such action.

4.39

The timing and form of Australia's response must be in sync with the

global response, particularly the targets set by the United States and other

developed nations.

4.40

The committee also notes that the Shergold report, commissioned by the

previous federal government, proposed the following timetable:

-

2008—a long-term aspirational target would be set and an

emissions reporting and verification system established

-

2009—finalisation of key design features and establishment of the

legislative basis of the scheme

-

2010—establishment of the first set of short term caps and

allocation of permits

-

2011, or at the latest 2012—commencement of trading.[17]

Recommendation 2

4.41

The committee recommends that the CPRS legislation not be passed in its

current form.

The mechanism of setting caps

4.42

The Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme Bill establishes that the national

scheme caps will be set in regulations. This section of the report looks at

those factors that will influence the setting of the emissions cap for a given

financial year.

4.43

Sections 13 to 15 of the Bill set out the procedure for the Minister to

follow in setting the annual emissions cap for each financial year.

4.44

It states that the Minister must 'take all reasonable steps' to ensure

that regulations stating the national cap for the year beginning 1 July 2015

are made at least five years before the end of the eligible financial year. For

each year subsequent to the 2015–16 financial year, the cap should be declared

at least five years before the end of that financial year.

4.45

Section 14(5)(a) states that in making a recommendation on the level at

which to set the national cap, the Minister must have regard to

Australia's international obligations under the Climate Change Convention and

the Kyoto Protocol.

4.46

Sections 14(5)(b) and (c) state that those factors to which the Minister

may have regard in recommending the level of the national cap are:

-

the most recent report given to the Minister by an expert

advisory committee under section 354 of the bill;

-

the principle that the stabilisation of atmospheric

concentrations of greenhouse gases at around 450 parts per million of carbon

dioxide equivalence or lower is in Australia's national interest;

-

progress towards, and development of, comprehensive global action

under which all of the major economies commit to substantially restrain

greenhouse gas emissions and all of the advanced economies commit to reductions

of greenhouse gas emissions comparable to the reductions to which Australia has

committed;

-

the economic implications associated with various levels of

national scheme caps, including implications of the carbon price;

-

voluntary action to reduce Australia's greenhouse gas emissions;

and

-

estimates of emissions that are not covered by the scheme.

4.47

The CPRS Bill 2009 includes changes from the exposure draft to the way

that scheme caps and gateways will be set.

4.48

First, clauses 14 and 15 of the bill now state that a written statement

must be tabled in parliament outlining the minister's reasons for the

regulations underlying the scheme caps and gateways.

4.49

Second, the Government has announced that as part of its consideration

of 'voluntary action' identified in paragraph 14(5)(c)(iv):

Additional GreenPower purchases above 2009 levels will be

directly recognised...[with] additional GreenPower purchases...measured annually

and future caps...tightened on a rolling basis.[18]

4.50

The Explanatory Memorandum to the CPRS bill elaborates:

The Government has indicated that additional GreenPower

purchases will be measured annually and taken directly into account in setting

scheme caps five years into the future, on a rolling basis. For example, the

2016-17 cap will be tightened to reflect the difference between 2009 and 2011

GreenPower sales, multiplied by a factor to reflect the emissions saved. This

will achieve emissions reductions beyond Australia’s national targets as it

will be backed by the cancellation of Kyoto units.[19]

Setting the cap - the need for certainty

4.51

The Committee heard evidence that it is important for business to know

well in advance the level at which the cap will be set.

4.52

AGL gave evidence to the Committee that:

Without a doubt, the sooner we see the regulations the

better, but, for a company like AGL, the principal decision points for a

company investing in energy infrastructure are really what the targets will be.

We know what is proposed in the legislation for the first three years and the

gateway for 2020. From our perspective, when you think about modelling the carbon

price and incorporating that into a business decision, having the certainty

around what those targets are is the most critical thing, from our perspective.[20]

4.53

Woodside expressed similar concerns giving evidence that it is important

to have 'a sufficient amount of detail' in the legislation rather than in

regulations.

4.54

Mr Niegel Grazia of Woodside gave evidence that the long-term, large

scale nature of the company's liquefied natural gas investments meant it will

have to rely on 'two or three instances' of ministerial discretion for

continued assistance.[21]

4.55

The Energy Supply Association, the peak industry body for the stationary

energy sector in Australia, told the committee that the CPRS should incorporate

rolling scheme caps:

We believe that the CPRS should also commit to 10 years of

rolling scheme caps, followed by a 10-year rolling gateway. The energy industry

recognises that the setting of scheme caps and gateways requires a balance

between economic efficiency and policy flexibility to allow the government to

respond to changes in scientific knowledge and international commitments.

However, the government is the only entity that can commit Australia to

international negotiations and therefore the government should bear the risk of

future scheme caps and/or gateways being inappropriate. With long-lived,

capital-intensive infrastructure, the industry cannot be expected to bear this

risk.[22]

The need for political independence

4.56

The committee also heard that the task of setting the cap should be the

responsibility of an independent statutory authority, not the Minister.

4.57

This view was flagged by the President of the Australian Council of

Trade Unions, Ms Sharan Burrow:

... The more I think about it, the more I think we need an

independent monitoring assessment authority—a statutory authority as

appropriate. It does seem to me that the work of making sure that the

commitments, the transparency, the effort—whether it is decay, the situation of

corporations or all of those things—requires an incredibly detailed and

scientific base. With due respect, for that to come back to a political

authority from any party does not seem to me the way we would run any other

major part of the economy...I would urge the committee to consider the role and

whether a statutory authority or some other such independent body is not a

better way to set Australia up for a scientific base to these considerations,

as opposed to the normal cut and thrust of political decision making.[23]

4.58

Some witnesses expressed concern that the CPRS, as proposed, does not

have an adequate governance framework.

4.59

Dr Regina Betz of the Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets

contrasted the Government's Draft Exposure Bill with the electricity market,

which has a clear separation of policy (the Ministerial Council on Energy and

COAG), a rule-maker (the Australian Energy Market Commission), a regulator and

an organisation responsible for operational aspects. Any party can put forward

a proposed rule change at any time, and then a formal process begins. She

added:

I do not think we see anything like that rigour in what is

currently proposed for governance for this scheme. The one thing we do know is

that, when the scheme initially goes in, we will make mistakes, potentially

very significant mistakes. Our ability to correct those is going to be a key

part of success or failure.[24]

4.60

Evidence was also given that if ministerial discretion is to be applied

effectively in adjusting a trading scheme, it must set a principled standard.

4.61

This point was made by Dr Iain MacGill, also a director of the Centre

for Energy and Environmental Markets:

At one level if you are very outcome focused then a great

deal of ministerial, hence political, direction can go one way or the other. It

might be very productive and allow very important changes to be made in the

timescale that might be required. However, in the general sense we look to

establish processes that provide guidance on how decisions will be taken with

some view as to the boundaries of those. If we look at the national electricity

market, there are opportunities for significant political discretion to play

out. However, there is a very conscious attempt to establish a process by which

you will establish a basis of fairness or appropriateness as to such discretion

being exercised.[25]

Setting the cap - the need for flexibility

4.62

The committee heard from some witnesses that there must be flexibility

in setting the cap to allow for both a strong international agreement and

adjustment to take scientific factors into account.

4.63

Environment Business Australia argued:

Originally the concept of the CPRS was for it to be a

flexible market mechanism. It has lost a lot of its flexibility and market

aspect as well. In terms of the nimbleness, I think the five-year gateways may

be a problem because we may need to reset those given the science that is

coming out. We need to be far more flexible if we do need to set much stricter

year‑by‑year targets for emissions cuts.[26]

4.64

Dr Graeme Pearman, a former Chief of CSIRO Atmospheric Research,

gave evidence that:

...you do not lock in any of the agreements for too long

because the uncertainty exists and will solve some of those problems and will

understand them better in another year's time and another. At that point in time

you do not want to be locked in for 20 years in terms of how you respond.[27]

Exceeding expectations

4.65

The committee also received evidence that in setting the cap, it is

important to take account of complementary measures such as energy efficiency

initiatives, soil sequestration and investment in renewable energy.

4.66

The Hon. Tom Roper, President of the Australian Sustainable Built

Environment Council, gave evidence that:

...it is very important in both determining the mix of measures

that are being taken and doing a proper sum on how that affects the cap. Let us

take the CIE material on buildings. If you effectively, through a series of measures,

save 52 million tonnes of carbon in the building area, that will clearly change

the way in which you might determine a cap and will also change your estimate

of what costs will be. The macroeconomics people really need to examine that.[28]

4.67

Ms Burrow expressed her concern the 2020 cap may underestimate the

potential for abatement from complementary measures:

Having that cap to 2020 will deny us the right to actually

measure what we are doing. I think, in green building retrofit schemes alone,

in the built sector, we can do more. In soil sequestration we could actually

take a lot more carbon—indeed, legacy carbon—out of the atmosphere a lot quicker

than we will get to do from the ambitions in an ETS.[29]

Carbon leakage and arguments for assistance for

trade-exposed firms

Carbon leakage

4.68

The government has defined carbon leakage as:

The effect when a firm facing increased costs in one country

due to an emissions price chooses to reduce, close or relocate production or to

close or relocate production to a country with less stringent climate change

policies.[30]

4.69

The main argument made for assistance to industry is to address the risk

of 'carbon leakage'. In this regard, the government has recognised the need to

provide assistance to industry in the White Paper. The White Paper

stated:

Australia’s adoption of a carbon constraint before other

countries may have a significant impact on its emissions-intensive

trade-exposed industries. The Government is committed to providing assistance

to these industries to reduce the risk of carbon leakage and provide them with

some transitional assistance.[31]

4.70

The issue of carbon leakage was a particular concern of the Senate

Select Committee on Fuel and Energy.

4.71

At paragraph 5.111 to 5.113 of the majority Interim Report, it stated:

In conclusion, the majority of evidence received by the

committee on the issue of the international competitiveness of Australian

industry and carbon leakage can be summed up with the following quote: 'it

would be a perverse outcome if the implementation of the CPRS in Australia led

to a result which added to global emissions.'

Committee comment

The committee considers that in the absence of an appropriate

global framework the CPRS as currently designed will not sufficiently mitigate

the risk of carbon leakage.

The committee is of the view that:

-

EITE assistance should be expanded

so that it is based on production rather than on an activity basis;

-

EITE assistance should be

maintained at commencement levels until major competitors face comparable

carbon costs;

-

The coal mining industry should

not be excluded from EITE assistance;

-

Appropriate recognition should be

given to those industries that contribute to a global reduction in emissions,

such as LNG.[32]

4.72

The committee recognises that there are many ways in which carbon

leakage can occur. For example through a company closing its Australian

facility and opening a new facility in a country without a carbon price.

Alternatively, whereby the Australian producer gradually loses market share to

an overseas competitor as a result of Australia introducing a price for

greenhouse gas emissions. In this scenario, existing plants may continue to

operate but there will be no new investment.

4.73

The committee agrees with the conclusion of the Select Committee on Fuel

and Energy that 'it would be a perverse outcome if the implementation of the

CPRS in Australia led to a result which added to global emissions'.[33]

Evidence of serious concerns

4.74

Many industry representatives raised carbon leakage as a real and

serious concern.

4.75

For example, Mr Andrew Canion, Senior Advisor, Industry Policy, Chamber

of Commerce and Industry of Western Australia, gave evidence that his

organisation have been advised by its members that the risk of carbon leakage

is real and that a rational economic business decision would be to invest where

it is the least costly to do so:

We have been advised by our member companies that the risk of

carbon leakage is real and that a rational economic business decision would be

to invest where it is the least costly to do so. We have further been advised

that there is a risk that, should Australia introduce an emissions trading

scheme of itself without complementary action internationally, a rational

business decision would be to look at those other options. [34]

4.76

Mr Frank Topham, Manager, Government Affairs and Media, Caltex Australia

Ltd, provided evidence to the committee that:

I think under the CPRS carbon leakage will be a very grave

threat to Australian manufacturing industries, including oil refining. It is

very difficult to quantify at this stage what the exact impact would be.[35]

4.77

Mr Timothy McAuliffe, Manager, Environment and Sustainable Development

for Alcoa of Australia provided evidence to the committee that:

Alcoa believes there are a number of key changes that need to

be made to its [CPRS] design to ensure it does not lead to carbon and jobs

leakage from the Australian aluminium industry.[36]

4.78

Mr Bradley Teys, Chief Executive Officer, Teys Bros Pty Ltd, gave the

following evidence to the committee:

I just want to make sure that the scheme we put in for the

cattle and livestock industry does not in fact reduce our exports so that

Brazil, which is 40 per cent less efficient, picks them up and we have carbon

leakage.[37]

Alternative views

4.79

Ms Meghan Quinn, a representative from Treasury, gave evidence that:

A modelling organisation called CICERO, which is a reputable

organisation within Europe, estimates that carbon leakage would be under three

per cent for the entire Kyoto regime between developed countries and developing

countries. Similarly, in the modelling produced in the Australia's low

pollution future report, we found that, once emissions-intensive trade‑exposed

industries had been allocated permits under the 90-60 per cent ratio in the Green

Paper, there was little evidence of carbon leakage in the economic models

that we used.[38]

4.80

Other witnesses also questioned the likely extent of carbon leakage:

But most estimates are that it is quite moderate—in the order

of five to 15 per cent. One of the key factors is that these are very

capital-intensive industries, so they make decisions on location not only on

the prices today but on ... whether there will be a carbon price—in 10 or 15

years time...even if countries like China do not have an explicit carbon price

today... there is quite a probability that they will have a carbon price by 2015

or 2020.[39]

The relative magnitude of leakage varies across different

models, depending on the assumptions, and it can be somewhere between five per

cent and 20 per cent.[40]

Assistance to emissions-intensive, trade-exposed industries

(EITEs)

4.81

The government has recognised the need to provide assistance to industry

in the White Paper. The White Paper stated:

Australia’s adoption of a carbon constraint before other

countries may have a significant impact on its emissions-intensive trade-exposed

industries. The Government is committed to providing assistance to these

industries to reduce the risk of carbon leakage and provide them with some

transitional assistance.[41]

4.82

The Government proposes to provide free permits to some EITEs. The permits

provided will be based on the industry's historic average emissions intensity,

avoiding penalising individual firms who are lower than average polluters and

retaining an incentive for firms to cut emissions. Assistance will be linked to

production: expanding firms will receive an increased number of permits and

contracting firms will receive fewer permits. A firm which ceases to operate in

Australia will no longer receive permits.

4.83

Firms that are able to produce the same quantity of output with fewer

permits than are provided will be able to sell the difference. In effect, they

will receive credit for performance better than the baseline. Firms with

emissions above the baseline level will have to buy additional permits. To some

extent this part of the CPRS operates like a 'baseline and credit' or

'intensity' system, and is subject to some of the criticisms made about such

schemes.[42]

4.84

Trade exposure will be assessed based on either having trade share

(average of exports and imports to value of domestic production) greater than

10 per cent in any year 2004–05 to 2007–08 or a 'demonstrated lack of capacity

to pass through costs due to the potential for international competition'.[43]

Emissions intensity refers to emissions relative to either revenue or value added,

averaged over the lowest four years from 2004–05 to 2008–09.

4.85

The initial assistance announced in the White Paper envisaged

permits to the value of 90 per cent of the allocative baseline for activities

with emissions intensity above 2000 tonnes CO2e per million dollars

of revenue or 6000 tonnes CO2e per million dollars of value added.

Permits to the value of 60 per cent of the allocative baseline would have been

provided for activities with emissions intensity of 1000 to 2000 tonnes CO2e

per million dollars of revenue or 3000 to 6000 tonnes CO2e per

million dollars of value added.

4.86

The White Paper suggests that, for example, aluminium smelting

and integrated iron and steel manufacturing are likely to qualify for the 90

per cent assistance and alumina refining, petroleum refining and LNG production

as likely to qualify for 60 per cent assistance. If the CPRS is extended to

cover agriculture, it is likely that beef cattle, sheep, dairy cattle, pigs and

sugar cane would qualify for assistance.[44]

4.87

The changes announced by the Government on 4 May 2009 increase these

assistance rates for at least five years. Under what the Government refers to

as the 'Global Recession Buffer', those firms previously eligible to receive 90

per cent free permits will now receive 95 per cent while those previously

eligible for 60 per cent will now receive 66 per cent.

4.88

The 66 and 95 per cent assistance rates will be gradually scaled down

over time, by an arbitrary 1.3 per cent a year.[45]

Some industries doubt that they will be able to achieve 'carbon productivity'

improvements at this rate:

For aluminium smelting, annual ongoing improvement rates of

1.3 per cent are technologically unachievable. Australia’s aluminium smelters

currently are run at or close to benchmark performance levels on an

international scale.[46]

4.89

The Committee notes that in New Zealand the phase out of free permits

does not start until after 2018.[47]

4.90

The argument for concentrating assistance on the EITEs is that other

industries will not be adversely affected:

...if they are not emissions intensive then the costs they will

face will be very low. If they are not trade exposed, that means that all

participants in that industry in Australia will face similar costs and they can

raise prices and pass it on to the community.[48]

Elaboration on five-yearly reviews

of EITE assistance

4.91

The Government has announced that in conducting the five-yearly reviews

of EITE assistance, the Expert Advisory Committee will consider:

(a) the review of eligibility assessment for activities (e.g.

taking into account falls in commodity prices etc as outlined in policy

position 12.8 in the White Paper);

(b) whether modifications should be made to the EITE

assistance program on the basis of whether it continues to be consistent with

the rationale for assistance or is conferring windfall gains on entities

conducting activities;

(c) the extent to which the Scheme has resulted in an

increase in the cost of electricity and the extent of pass through to EITEs;

(d) the extent to which EITE firms are making progress

towards world’s best practice energy and emissions efficiency for their

industry sector;

(e) the future shape of the permit price cap, recognising the

need to balance the development of market mechanisms and business certainty;

(f) international developments, including the extent to which

Australia has entered international agreements, tangible emissions abatement

commitments have been made by countries which compete with EITE industries, and

major partners or competing countries have introduced carbon constraints into

their own economies; and

(g) whether broadly comparable carbon constraints (whether

imposed through an explicit carbon price or by other regulatory measures) are

applying internationally, at either an industry or economy-wide level, or an

international agreement involving Australia and all major emitting economies is

concluded, in which case the Committee would make recommendations to Government

with regard to the withdrawal of EITE assistance; this assessment will draw on

analysis by an independent expert body (initially the Productivity Commission)

of quantitative measures of carbon prices or shadow carbon prices in major

economies. [49]

Critiques of the free permits to EITEs

4.92

Criticism of the assistance programme has come from companies who argue

it still leaves them disadvantaged relative to international competitors. For

example, representatives of the LNG industry gave evidence that the proposed

level of assistance is not adequate for their sector:

As the world's cleanest fossil fuel, with a major role to

play in reducing global greenhouse emissions, it is our view that LNG projects

should be nurtured rather than constrained. Anything less than a 100 per cent

permit allocation until competitor countries are subjected to a carbon cost

will disadvantage and tend to constrain Australia's LNG industry.[50]

4.93

Mr Frank Topham of Caltex Australia Ltd presented evidence to the

committee concerning the inadequacy of EITE assistance in his sector.

...we suggest that until overseas competitors have equivalent

carbon costs then there should be no effective carbon costs imposed on

Australian refineries. Under the CPRS that could be done by way of the

allocation of free permits.[51]

4.94

The Minerals Council of Australia presented evidence to the Standing

Committee on Economics that most its industry remained unshielded:

The changes marginally raise the level of support for the now

infamous emissions-intensive trade exposed industries, but that shielding is

still below that provided or proposed by other nations, severely undermining

our international competitiveness. In addition, those changes are simply irrelevant

for nine out of 10, or 90 per cent, of Australia’s minerals exports, which

receive no shielding and, therefore, will face the highest carbon costs in the

world—again, that our competitors do not face.[52]

4.95

The coal industry also provided evidence that it was not adequately

assisted. The situation of the coal industry is discussed in further depth below.

4.96

Mr Charles McElhone, Manager, Trade Policy and Economics, National

Farmers' Federation provided evidence to the committee that the short term

impact of the CPRS on the supply chain for the agriculture sector had not been

adequately considered:

Senator CASH—In your opening statement, you commented that

the agriculture industry is not covered but affected—in other words, the CPRS

is at this particular point in time not going to cover you until 2015. Can I

get a better understanding of why you are saying that your industry is affected

prior to this time?

...

Mr McElhone—Basically, if you look at the cost profile of the

Australian farming sector, such as the cropping sector, about 45 per cent of

our costs are energy or energy dependent. So we are talking about fuel use,

electricity use, crop contracting and fertiliser use. All those costs will be

affected.

Senator CASH—When you say ‘affected’, do mean negatively or

positively?

Mr McElhone—All those costs will go up. At the same time, it

should be acknowledged that with such an internationally exposed sector and,

disappointingly from our perspective, a real incapacity to pass on those costs

as a result, even small increases in cost are going to have large ramifications

on our competitiveness to export. We export about two-thirds of what we

produce. From that perspective, we will be affected upfront.[53]

4.97

Other witnesses in their evidence argue that the assistance, especially

after the Government increased it in its 4 May announcement, is excessive:

I think the assistance was already excessive. Of course, it

benefits a vociferous and influential group of companies who have spent a lot

of time and money to convince the community that action is very expensive and

that handing them billions of dollars of free permits is in the public

interest. I do not believe it is. Indeed, even before the additional

largesse...some highly emitting firms in the 90 per cent bracket actually being

better off under the CPRS package than if there was no action on climate change

at all... firms with emissions that are below industry average but still much

higher than other parts of the Australian economy—but lower than their very

high-emitting counterparts—stand to receive more permits than their total

emission liabilities...firms will have opportunities to reduce their emissions in

light of carbon pricing but will be given the historic industry average.[54]

...we are seeing a lot of innovation at the moment, but it is

lobbying innovation, and that appears to be where the returns are in the

governance arrangements as they currently stand.[55]

4.98

Other witnesses gave evidence that the extent of free permits to large

polluters is unfair. For example, the Committee received over form letters,

prepared by the Australian Greens, arguing:

The CPRS as is stands is a pay-the-polluter scheme, not a

polluter-pays scheme. By providing Australia's

worst polluters with billions of dollars of compensation in cash and free

permits to pollute, the CPRS will protect the profits of Australia's

worst climate offenders at the expense of clean industries.

It also unfairly transfers the cost of reducing emissions to

industries with less lobbying power and to the community at large. Every dollar

of compensation that goes to polluters is a dollar less to assist householders

and clean industries.[56]

4.99

Similar points were made in many individual submissions.[57]

4.100

It is noted by the Committee that despite raising their objection to the

extent of the issue of free permits, no solution was put forward as to how to

address the concerns raised by industry in relation to their potential to be

disadvantaged relative to international competitors.

4.101

Some witnesses from the financial sector opined that the proposed

assistance in the CPRS would be adequate to address concerns about carbon leakage,

so that the impact of the scheme on companies would be manageable:

We looked at industries including steel, cement, aluminium

and LNG. We concluded that the scheme’s impact was generally in the order of

one to five per cent of company value or a little more under some scenarios.[58]

...our members believe that transitional assistance is

necessary for trade‑exposed sectors and consider that the revised

arrangements leave exposed companies with negligible financial impacts in the

short to medium term. Research by Goldman Sachs JBWere...has shown that the

financial impact of the CPRS will be minimal for listed Australian companies.[59]

Impact on competitiveness

4.102

Many industry submissions argued that Australian firms will be unable to

compete internationally if they are required to meet the cost of their carbon

emissions while foreign competitors in the developing world are not. Ms Belinda

Robinson of the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association

provided evidence to the Committee:

It remains the case, even after the Prime Minister’s recent

announcements, that the industry will be subject to a significant cost burden

that is not borne by its LNG competitors—including countries such as Qatar,

Algeria, Nigeria, Trinidad and Tobago, Egypt, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Oman

and the United Arab Emirates—or our customers. This means a constraint to

growth and a consequent increase in global emissions as less Australian natural

gas is made available to the world. We do not believe that this is the outcome

that should reasonably be expected from any policy that has as its core an

objective to reduce emissions.[60]

4.103

Mr Ralph Hillman, Executive Director of the Australian Coal Association,

provided the following evidence to the committee:

Notwithstanding the poorer quality of Indonesian coal, our

friends in New Zealand prefer it to Australian coal. Notwithstanding their

infrastructure problems, it was because of the flexibility of their mining operation

compared with ours which requires massive railways and massive port facilities whereas

they can just throw it on a barge and then onto a boat. That is how they stole

15 per cent of our export market. The thing is that coal is everywhere. Most

countries have coal and there is a vast range of countries in a position to

export it and in a position to beat us on a cost basis, so every cent counts.

Of course, every country has its advantages and disadvantages. Australia has superb

quality coal. We are a properly regulated economy. We have some very good infrastructure;

we have a lot of things going for us, but we also have higher labour costs. Our

mines are getting further and further inland from the coast. Our mines in the

Hunter Valley, for example, are getting deeper; therefore gassier and more

expensive to operate. Our mines in the Illawarra are getting deeper and deeper,

gassier and more expensive to operate. So it is a dynamic situation and every

little thing you load onto the industry makes it harder for the industry.[61]

4.104

Other witnesses regarded this as overstated, pointing to the operation

of the floating exchange rate.[62]

Transitional assistance to EITEs

4.105

As noted above, as well as carbon leakage, the Department of Climate

Change justified assistance to EITEs as follows:

...the government is attempting to smooth the transition for

individual firms, rather than just have them take a hit on their profit.[63]

4.106

Some other submitters also explained the need for transitional

assistance:

The draft legislation clearly demonstrates to us an

appreciation of the fact that the Australian economy will require a period of

transition to become a low-carbon economy. There is also a recognition of the

potential competitiveness at threat for some aspects of the Australian industry.

We can also see evidence in the legislation that the government has considered

the emissions trading schemes in other jurisdictions and has looked to learn

from the mistakes and some of the challenges that have been experienced with

those schemes.[64]

The overriding consideration for the AWU has been to ensure

that the EITE industries most exposed to the impacts of the ETS, and least able

to pass on costs associated with participation in the Scheme have the maximum

level of assistance during the transition to an international framework for

emissions trading (which includes both developed and developing countries) on a

true burden sharing basis.[65]

Additional assistance to the coal mining industry

4.107

Coal mining is excluded from EITE assistance. The White Paper

provided the following explanation:

Since the majority of coal mines are not emissions-intensive,

the Government will not provide EITE assistance to the activity of coal mining.

(An allocation based on the industry average would lead to the majority of coal

mines receiving significant windfall gains.) However, a small number of coal

mines are very emissions-intensive and will face a significant cost impact from

the Scheme. The Government will allocate up to $750 million from the Climate

Change Action Fund to facilitate abatement and assist with the transition of

these coal mines.[66]

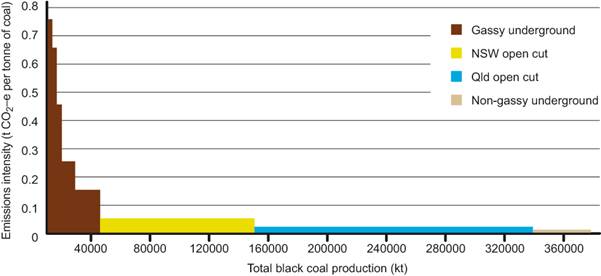

Chart

4.2: Black coal mine fugitive emissions intensity (2006-07)

Source: White Paper, p

12-46.

4.108

As set out in the Select Committee on Fuel and Energy Interim Report:

Coal is Australia’s largest commodity export, earning over

$40 billion in 2008. Australia is also the world’s largest exporter of coal,

exporting over 250 million tonnes in 2008. The black coal industry employs over

30,000 Australians directly and a further 100,000 indirectly. It provides 57

per cent of our electricity generation. When we add in brown coal, that figure

rises to over 80 per cent. Coal therefore underpins the security, reliability

and comparatively low cost of Australia’s electricity supply. In turn, this supports

the competitiveness of Australian industry and provides affordable power for

Australian households.[67]

4.109

The Government decided to treat coal as a special case. However, this

reasoning was not accepted by the black coal industry's representatives:

We are just asking for fair treatment under the CPRS and

under the ET arrangements. Coal clearly meets the white paper eligibility

criteria for a 60 per cent permit allocation.[68]

4.110

The black coal industry's response to the issue of 'windfall gains' was

to suggest:

...instead of allocating permits mine-by-mine according to each

mine's production you actually recognise the coal industry is different from

cardboard box manufacturing or aluminium production, you allocate them

according to each mine's emissions...[69]

4.111

The Government intends to allocate up to $750 million in targeted

assistance to the coal industry, around two-thirds of which will go to 'gassy

mines' to assist in the installation of abatement equipment.[70]

This is well below the assistance the industry would receive were it to be

treated as an EITE.

Assistance to electricity generators

4.112

The Government will assist electricity generators through the

Electricity Sector Adjustment Scheme (ESAS), which will provide an amount of

free permits, worth about $4 billion over five years.

4.113

The Energy Supply Association of Australia argued that this is well

below the damage they will suffer as a result of the CPRS:

The government has effectively short-changed the industry by

tabling only $3.5 billion in its White Paper. This is likely to result

in distress across multiple coal-fired assets and it will affect both debt and

equity stakeholders... I think you are looking at more like between $10 billion

and $20 billion. It is $10 billion, according to two out of the three models by

Treasury, to 2020.[71]

The CPRS needs to adequately address the stranding of

coal-fired generation assets. A measured transition to full auctioning, as

proposed in most other schemes to date, would enable a greater volume of

permits to be administratively allocated to affected generators to ensure there

is no disproportionate loss of economic value on the sector's balance sheets

which would compromise both the ability to refinance existing assets and to

make new investments.[72]

4.114

The Association warned that the CPRS was a threat to the solvency of

some generators:

I am concerned that coal-fired assets in particular will find

their cost base significantly increased, some by a 200 to 400 per cent increase

depending on the CO2 price. In turn that will result in insolvency

or near insolvency and certainly a reduced ability to do maintenance. In turn

that could lead to reduced energy security or energy supply. It would certainly

increase energy security risk.[73]

4.115

Other witnesses referred to the problems that were being caused for

firms wishing to fund investment from international lenders:

...ERM Power is now marking time before proceeding to arrange

finance ...The $1.8 billion of finance for these projects will not be obtainable

unless lenders and investors are reassured that the Australian electricity

sector can maintain its high credit rating. Although the threat of properly

made investments in coal fired power stations being stranded does not affect

gas fired generators... the remaining international lenders are even more

sensitive to changed country risk and particular sector risks.[74]

4.116

The Government argument for the ESAS assistance is that the CPRS:

...will impose a new cost on fossil fuel-fired electricity

generators...relatively emissions-intensive generators are likely to face a

greater increase in their operating costs than the general increase in the

level of electricity prices...[and] lose profitability...if investors consider that

the regulatory environment is riskier...all investments in the sector could face

an increased risk premium.[75]

4.117

The justification for ESAS is that a government decision has 'changed

the rules' and so the affected companies should be compensated.

4.118

An alternative view is that compensating the generating companies for a

reduction in the value of their assets would represent a change to the standard

approach of Australian governments.[76]

Professor Garnaut commented:

There is no public policy justification...Never in the history

of Australian public finance has so much been given without public policy

purpose, by so many, to so few.[77]

Treatment of voluntary/additional emission

reductions

4.119

The committee received hundreds of submissions objecting to the effect

of the proposed CPRS on households and businesses' voluntary actions to reduce

their greenhouse gas emissions.[78]

The submissions highlighted the fact that under the proposed CPRS, households'

voluntary actions will not affect the overall level of emissions.

4.120

In this context, 'voluntary' action refers to things that are done for

(or primarily motivated by) altruistic concerns about the environment rather

than (just) in response to a price signal.

4.121

For example, electricity consumers who opt to pay more for electricity

derived from renewable sources rather than fossil fuels. Another example is the

installation of solar panels where the installation costs exceed the savings on

power bills.

4.122

For example, under the Government's original proposal, a household that

chooses to buy the more expensive option of GreenPower will lead their

electricity supplier to make fewer emissions and need fewer permits. This would

mean that there are more permits for other polluters to purchase and increase

their emissions. As such, the CPRS would act as a disincentive for households,

and the many businesses not covered by the scheme, to reduce their carbon

footprint. Any voluntary actions that these groups do make will not lead to a

reduction in Australia's greenhouse gas emissions.

4.123

This situation was also highlighted in several submissions to the Senate

Economics Committee as part of its inquiry into the Exposure Draft of the bill.

4.124

The Economics Committee observed:

The growing perception that the CPRS negates actions taken by

individual households to reduce emissions is eroding support for the scheme.

This must be addressed.[79]

Views on the voluntary action issue

4.125

Many individuals and organisations identified a key concern with the

proposed CPRS as its failure to take into account the voluntary actions of

households, (non-liable) businesses and state and territory governments. The

committee received a form letter, prepared by the Australian Greens, from over

one thousand submitters stating:

In addition to setting such a weak 5% target, the CPRS also

fails to take into account voluntary emission reductions from the community.

The efforts of everyone from householders to State Governments to reduce

emissions will be helpful only in reducing the price pressure on polluters.

This must be fixed by taking account of community action and all the policies

already in place when setting the scheme caps, and using the scheme to drive

more ambitious efforts.[80]

4.126

A small sample from the hundreds of individual submissions from

concerned citizens say:

It is also of concern that the CPRS, as proposed, does not

take into account voluntary emission reductions from the community. The efforts

of everyone from householders to State Governments to reduce emissions will be

helpful only in reducing the price pressure on polluters. This must be fixed by

taking account of community action and all the policies already in place when

setting the scheme caps, and using the scheme to drive more ambitious efforts.[81]

I have recently upgraded my home to be as energy efficient as

possible, and have installed solar hot water and a photovoltaic system for

renewable electricity. I am dismayed to find that, with the CPRS in its current

form, my actions (and considerable money spent!) amount to nothing. They

essentially just free up permits for polluters.[82]

My family and I have gone to considerable effort and expense

to reduce our carbon emissions, such as installing a solar water heater and photovoltaic

grid interactive solar panels. We think it is scandalous that the government's

proposed carbon trading scheme would not take such efforts into consideration,

and that they would in fact allow polluters to pollute more. Such efforts

should be encouraged by the government, not undermined by such poor policy.[83]

Ordinary Australians are willing to assist with reducing

Australia's carbon footprint and their contribution should not enable big

polluters to pollute more, but should make a measurable difference. Otherwise,

I fear that householders and small business will fail to see the point in doing

their bit for the environment or paying the extra for the CPRS.[84]

If a cap and trade system is chosen, it must recognise the

benefits of voluntary actions and not allow these to do the job of the big

polluters. The cap should be lowered by the amount of voluntary reductions

achieved by individuals and businesses.[85]

4.127

Several organisations also voiced their concerns.

4.128

The Executive Director of the Australian Conservation Foundation,

Mr Don Henry told the Committee:

I think there is a problem with voluntary action. The

Australia Institute has raised it and companies like Origin have raised it, as

have many of the green power providers. I think it is really important that

people know that what they do can make a difference. It is an important

motivating factor, and that is also why we would have the view that other

complementary or additional measures are really important here...There are things

that we need to be doing, and a price signal through the proposed CPRS, for

example, will not be adequate alone, and action is required. You have to

ensure, whether it is an individual household or a commercial building doing a retrofit,

that they can see the benefit of their action, or are required to act.[86]

4.129

The South Australian Government argued in its submission that the design

of the CPRS could be improved by providing for recognition of some forms of

abatement action undertaken on a voluntary basis by households and individuals.

It identified the purchase of GreenPower and the installation of solar panels

as the principal actions which should be recognised. The submission noted three

reasons why voluntary action must be taken into account. First, it is important

to capture 'a particularly cheap form of abatement'. Second, recognition of

voluntary action directly supports investment in clean energy, energy

efficiency and jobs. And third, the exclusion of voluntary action means that

the commitments of state governments and corporations to voluntary action are

no longer encouraged.[87]

4.130

The ACT government also argued in its submission that the programmes of

state and territory governments which reduce greenhouse emissions beyond levels

required by the CPRS should be recognised in the scheme. The Territory's

Environment Minister, Mr Simon Corbell MLA, expressed 'significant

concern' that state and territory jurisdictions may not be able to implement

more stringent climate change policies. He urged the Commonwealth Government to

investigate how these efforts by states and territories can meaningfully

contribute to reducing greenhouse gases.[88]

A design feature

4.131

Other witnesses did not view the voluntary action issue as a problem.

Dr Frank Jotzo, an economist at the Australian National University, argued

in his submission that the alleged oversight of voluntary abatement efforts is

not a design fault of the CPRS. Rather:

Individual action is an integral part of achieving a national

emissions reduction target at least cost, and it will be encouraged by rising

energy prices. The more individuals do to reduce their greenhouse gas

footprint, the easier it will be for Australia collectively to meet any national

emissions target. That in turn will make it possible to go for more ambitious

national targets down the track. That of course requires flexibility in being

able to ratchet down targets in the future, and the political preparedness to

do so.[89]

4.132

In its submission to the Senate Economics Committee's inquiry into the

Draft Exposure Bill, the Australian Industry Group opposed the bill's clause

guiding the Minister to consider voluntary action in setting the cap:

Ai Group does not understand what of substance is intended by

including among the factors that may be taken into account in setting caps the "voluntary

action"... Our understanding is that an ETS (or a carbon tax) would

encourage households and businesses to reduce emissions by imposing a price... Ai

Group submits that the concept of voluntary action should be removed from the

list of factors that can be taken into account in setting caps.[90]

4.133

Mr David Pearce of the Centre for International Economics told the

Senate Economics Committee in March this year that far from being a problem,

the voluntary abatement issue was in fact a benefit of the CPRS scheme. He

argued that voluntary action undertaken by households lowers the demand for

permits, which lowers the price of permits and thereby makes abatement less

costly for everybody.[91]

Possible ways of recognising voluntary emission reductions

4.134

The committee heard that voluntary efforts to reduce greenhouse gas

emissions should be accounted for in a systematic and structured way. Mr

Timothy Hanlin, Managing Director of Australian Climate Exchange Limited, stressed

the need for a government sponsored voluntary emissions trading scheme. He

explained:

We believe that the CPRS needs mechanisms that, for instance,

buy back permits from the market and therefore maintain the cap equivalent to

the reductions that are achieved in that voluntary emissions trading scheme. We

also believe that at least five per cent additional reduction by 2020 could

very easily and conservatively be achieved through voluntary measures. We point

to Europe and the fact that post the introduction of an EU emissions trading

scheme, Europe has been the largest market growth in voluntary emissions trading

of anywhere else in the world.[92]

4.135

Dr Richard Denniss has argued that the Exposure Draft of the CPRS

bill should be amended to allow the number of permits to be reduced each year

directly in line with the amount of pollution saved by voluntary action. The

creation of a secondary market of permits based on households' emissions

reductions would enable household emission reduction permits to be exchanged

for CPRS permits. To account for difficulties in the accuracy of household

emissions measurements, Dr Denniss proposes that secondary market permits be

exchanged for CPRS permits at a fixed rate of 2 to 1. If two tonnes of

household permits was exchanged for a tonne of CPRS permits, 'it is impossible

for the secondary market in household efficiency permits to dilute the value of

CPRS permits so long as the measurement error is less than 50 per cent'.[93]

4.136

The Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets at the University of New

South Wales has proposed that voluntary action could be recognised through an

Additional Action Reserve (AAR). The AAR would annually set aside a proportion

of emission units which would be retired if governments, businesses or

individuals take emission reduction measures which go beyond a baseline target

that emitters are expected to achieve. Through setting aside a fixed proportion

of units annually, the Action Reserve would limit recognition of voluntary

action and limit potential losses of auctioning revenue. If the allocated

emission units are not retired in a given year, they would be returned to the

market. The Centre argues that a scheme along these lines would provide a

mechanism for 'defined and limited' strengthening of the national emission

target which would drive domestic emission reductions rather than potentially

draw on international carbon credit markets.[94]

The CPRS Bill 2009

4.137

The CPRS Bill and Explanatory Memorandum have made two broad changes to

the Exposure Draft legislation and Commentary in relation to the voluntary

abatement issue.

4.138

Evidence was given by Mr Blair Comley, Deputy Secretary of the

Department of Climate Change, as follows:

There are really two broad changes that have been made since

the exposure draft. The first change relates explicitly to green power and that

is making a commitment by the government that increases in green power above a

2009 baseline would be subtracted from the cap in the future cap-setting

process. That is an explicit commitment about green power above and beyond

general voluntary action. The second change, which is more a change of

explanation and emphasis, is that the explanatory memorandum provides

significantly more information than there was in the exposure draft about the

way in which voluntary action would be intended to be taken into account. That

was really an elaboration of what the government had in mind in the exposure

draft bill making it clear that it would monitor a range of different indicators

of voluntary and individual action and that would feed into the future

cap-setting process.[95]

4.139

As noted earlier, additional GreenPower purchases above 2009 levels will

be directly recognised when the government sets the caps. Additional GreenPower

purchases will be measured annually and future caps will be tightened on a

rolling basis. The Explanatory Memorandum to the CPRS Bill states:

The Government has indicated that additional GreenPower

purchases will be measured annually and taken directly into account in setting

scheme caps five years into the future, on a rolling basis. For example, the

2016-17 cap will be tightened to reflect the difference between 2009 and 2011

GreenPower sales, multiplied by a factor to reflect the emissions saved. This will

achieve emissions reductions beyond Australia’s national targets as it will be

backed by the cancellation of Kyoto units.[96]

4.140

Mr Comley also gave evidence that the Explanatory Memorandum gives

greater detail on the types of voluntary actions that the Government will

monitor and take into account when setting scheme caps and gateways.

4.141

The Explanatory Memorandum states:

A range of other indicators of voluntary action may also be

taken into account. As a matter of policy, the Government will monitor annual emissions

from the household sector, and will monitor and consider the uptake of certain

energy efficiency activities among households and businesses where there are

clearly defined business-as-usual benchmarks, and where improvements can be

detected. In doing so, the Government will consider trends in the construction

or renovation of houses to a star-rating above the minimum required, the use of

public transport and the expansion of public transport services, and the uptake

of more energy efficient appliances (particularly those that consume a

significant proportion of household energy such as water heaters and

airconditioners) beyond regulated levels. Action in these sectors could be

taken into account by assessing the extent to which the uptake exceeds historical

trends, factoring in electricity price changes, regulation and any direct

government assistance.

For example, the Government would collect data on the

proportion of houses with a 6 star rating that are being constructed, compare

this with historical trends and calculate the reduced emissions likely over the

full life-cycle of the buildings. This calculation could inform the

Government’s cap setting decision. Another example could be monitoring the

overall fuel efficiency of the passenger vehicle fleet in Australia. The trend

improvements in fuel efficiency could then be compared to historical trend

improvements, taking account of fuel price changes and other relevant factors.

Estimates of emissions reductions could then be used to inform the Government’s

decision regarding appropriate scheme caps and gateways. [97]

4.13 The EM does recognise that it is not possible to

list all household and individual actions that could be measured and taken into

account by the Minister. It notes that these 'may evolve over time in response

to changing carbon prices, technological developments and other economic and

social developments'.[98]

The Australian Carbon Trust

4.142

As part of a suite of changes to the Exposure Draft legislation

announced on 4 May 2009, the Government proposed to establish an

Australian Carbon Trust. The stated purpose of the Trust is 'to help all

Australians to do their bit to reduce Australia's carbon pollution and to drive

energy efficiency in commercial buildings'.

4.143

The Trust will have two components: a $50.8 million Energy Efficiency

Trust and a $25.8 million Energy Efficiency Savings Pledge Fund. The Pledge

Fund will enable households to calculate their energy use and retire carbon

pollution permits. The Government will establish a website for this purpose and

the pledges will be pooled with all contributions tax deductible. The Energy

Efficiency Trust will provide funding to cover upfront capital costs for

businesses seeking to undertaking energy efficiency measures. Businesses would

pass the cost savings back to the Trust at a commercial rate until the borrowed

costs (with interest) are repaid.[99]

4.144

A Government Media Release dated 4 May 2009 stated:

A new website will provide a one-stop shop for individuals

and households to simply calculate their energy use and buy and retire carbon

pollution permits under the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme...The Pledge Fund

will be entirely voluntary and contributions to the Pledge Fund will be tax

deductible.[100]

Responses to these measures

4.145

The committee sought comment on how effective the Pledge Fund would be

in resolving the voluntary action issue.

4.146

Dr Denniss remains a strong critic:

The proposal that was put forward is bizarre—that is the only

way to describe it. The notion that individuals who make decisions to use less

energy—be that through transport or in their household—would log on to a

website, calculate how much money they had saved on their electricity bill,

donate that money to Kevin Rudd and that he in turn would go and purchase a

permit from someone that they recently gave it to for free is just

inexplicable—bizarre. Add to that the fact that people might have spent extra money

of their own on buying a Prius or installing insulation in their house, if they

did not get the thing, or installing a solar panel—people are spending their

own money. And then, if they save electricity, they are expected to donate

money to the federal government. As to the argument, ‘At least it is tax

deductible now’: it was always tax-deductible if you donated it to an

environment group who went and purchased the permit. But the idea that the

solution to this is to purchase a permit...to pay twice—is just inexplicable.[101]

...

let us just stop the lying to consumers who are picking up

the tab through higher electricity prices through the MRET, through higher

taxes that are going to be needed to provide business with the certainty they

are after and through the fact that we are telling them to go and spend their

money on abatement measures that are not going to abate emissions at all.[102]

4.147

Other witnesses also identified the flaw in forcing households to 'pay

twice'.

4.148

Mr Russell Marsh of the Clean Energy Council told the committee:

The creation of the energy efficiency savings pledge fund

appears to be asking consumers to pay twice for carbon savings—firstly, when

they pay to install a certain bit of energy efficiency or renewable energy

equipment and, secondly, to have those permits retired from the market. It is

not quite clear exactly how that is going to work, but at first glance it

appears to be asking consumers to pay twice. There is a particularly strong

case to look at retiring permits associated with the installation of solar PV

on households. This is a technology that is getting a lot of financial support

from the government. There is a rebate scheme—the Solar Homes and Communities