Chapter 2

Science and emissions targets

2.1

There are essentially three stages in setting appropriate targets for

Australia's greenhouse gas emissions targets, drawing on different disciplines.

The first stage is examination of the relevant science to learn the

relationship between alternative levels of greenhouse gas concentrations in the

atmosphere and the associated probability of temperature increases and their

likely consequences. The second stage is to use these data to form a view about

the desirable limits to place on global greenhouse emissions. This process will

be informed by economics but is largely a matter of ethical or moral

considerations concerning what is a 'just' distribution of costs between

current and future generations. The third stage is to translate global

emissions targets into conditional and unconditional targets for Australian

emissions. This introduces considerations of national and international

politics and strategic bargaining.

Climate science

2.2

When concerns emerged in the scientific community that increased

emissions of greenhouse gases might be leading to global warming which if

unchecked could lead to dangerous climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel

on Climate Change (IPCC) was established to assemble and assess the best peer-reviewed

science on the topic from a range of relevant disciplines. Its reports have

been endorsed by the world's leading academies of science. Most scientists

submitting to the committee and appearing before it broadly endorsed the

findings of its 2007 report that warming of the climate system is unequivocal;[1]

and gave evidence, with a very high confidence that the increase in global

average temperature since the mid‑20th century is due to

anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations.[2]

A brief account of the science follows.

The greenhouse effect

2.3

There are a number of 'greenhouse gases'. The most important is carbon

dioxide (CO2). The others listed under the Kyoto Protocol are

methane, nitrous oxide, sulphur hexafluoride, hydroflurocarbons and perflurocarbons.

To express levels of the various gases as a single number, they are often

converted to carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e), where the conversion

factors reflect the warming potential of the various gases.

2.4

The 'greenhouse effect' involves the sun's light energy travelling

through the Earth's atmosphere to reach the planet's surface, where some of it

is converted to heat energy. Most of that energy is re-radiated towards

space—however, some is re‑re‑radiated back towards the ground by

the greenhouse gases in the Earth's atmosphere. Like a greenhouse, this keeps

temperatures higher than they would otherwise be. The effect has operated for

millions of years.

2.5

Human activities such as burning fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas),

agriculture and land clearing release large quantities of greenhouse gases into

the atmosphere, which trap more heat and further raise the Earth's surface

temperature.

2.6

The relationship between atmospheric concentrations of CO2

and temperature over time is shown in Chart 2.1. There are two important points

to note from the chart. Firstly, there is a clear long-run correlation between CO2

and temperature. This reflects a two-way mutually reinforcing causation; an

exogenous factor, such as variations in the Earth's orbit around the Sun, that

changes temperature will lead to a change in CO2, and a change in CO2

will lead to changes in temperature.

Chart 2.1: Atmospheric

concentration of CO2 and temperature (deviation from recent)

Source: CSIRO, 'Climate

change: the latest science', 2009.

2.7

Professor Robert Carter of James Cook University claimed that

temperature rises always preceded rises in CO2 concentrations.[3]

However, Professor Will Steffen, Executive Director of the Climate Change

Institute at the Australian National University, explained that the record also

includes times when greenhouse gas concentration increases preceded temperature

rises.[4]

2.8

The second point to note from Chart 2.1 is that, over the 800,000 years

shown, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 varied in a range from

around 180 to 280 parts per million (ppm) until the industrial revolution. It

has now risen to 380 ppm.

Global warming

2.9

Since modern measurements began in the late 1800s, global average

surface temperature has increased by around 0.7ºC–0.8ºC. Tree rings and other

records tell us that average Northern Hemisphere temperatures are likely to

have been the highest in at least the past 1300 years. The 13 hottest years

since the mid-19th century have all occurred in the past 14 years.

2.10

Global average annual temperatures from 1850 to the present are shown in

Chart 2.2. While there is a clear uptrend trend in the temperature data there

is volatility from year to year, reflecting factors such as volcanic eruptions

and the El Nino effect.

Chart 2.2

Source: calculated from data

from Bureau of Meteorology.

2.11

Some scientists place great emphasis on the average global temperature

in 2008 being lower than in 1998. Professor Bob Carter of James Cook University

interpreted this as indicating 'there is no warming at all, there is cooling'.[5]

However the climate scientists pointed out that 1998 was an outlying El Nino

year (Chart 2.2) and that 2008 was still hotter than any year prior to 1990.[6]

Professor Steffen, added that the less volatile ocean temperatures show a clear

warming trend.[7]

2.12

Media reports claim that an expansion of the ice area in part of

Antarctica provides evidence of global cooling. Dr Ian Allison, of the

Australian Antarctic Division in the Department of the Environment, Water,

Heritage and the Arts, explained that wind changes were spreading a decreasing

volume of ice over a wider area. He also drew attention to the localised impact

of the hole in the ozone layer, which until the reduction in use of CFCs allows

its repair, is likely to result in temperatures in some parts of Antarctica

being warmer than would otherwise be the case.[8]

2.13

It was put to the committee by Associate Professor Stewart Franks of the

University of Newcastle that any warming in the 20th century was due

to natural factors.[9]

However, as Chart 2.3 illustrates, climate models relying on natural factors

could not explain the warming in the 20th century but models that

incorporated increased greenhouse gas emissions from human activities could do

so.[10]

Chart 2.3: Modelling temperature increases

Source: CSIRO, The science of climate change.

2.14

In a 'business as usual' world the IPCC's median estimate is that

average temperatures will rise four degrees by 2100.[11]

Four degrees may not sound a lot. However, as Chart 2.1 shows, five degrees is

the difference between now and the last ice age.

Implications for Australia

2.15

The IPCC has predicted with high confidence that without mitigation, by

2100 a temperature rise of over four degrees in Australia would lead to water

security problems, and risks to coastal development and population growth from

sea-level rise and increases in the severity and frequency of storms. It

predicts with very high confidence that Australia would suffer a significant

loss of biodiversity in such ecologically rich places as the Great Barrier Reef

and the Queensland Wet Tropics, as well as the Kakadu wetlands, south-west

Australia, the sub-Antarctic islands and alpine areas. The IPCC predicts with

high confidence a decline in production from agriculture and forestry by 2030

over much of southern and eastern Australia due to increased drought and fire.[12]

2.16

The effects of climate change also carry national security implications:

...the cumulative impact of rising temperatures, sea levels and

more mega droughts on agriculture, fresh water and energy could threaten the

security of states in Australia’s neighbourhood by reducing their carrying

capacity below a minimum threshold, thereby undermining the legitimacy and

response capabilities of their governments and jeopardising the security of their

citizens. Where climate change coincides with other transnational challenges to

security, such as terrorism or pandemic diseases, or adds to pre-existing

ethnic and social tensions, then the impact will be magnified.[13]

More recent scientific observations

2.17

More recent evidence suggests that the 2007 IPCC report may prove

optimistic:

...the recent climate change congress in Copenhagen where we

had about 2,500 researchers from around the world [indicated]...We have good

evidence that shows that the climate system is tracking at the upper level of

the IPCC projections...In keeping with that, temperature and sea levels are also

tracking at or near those upper levels of projections.[14]

Support for the views of climate scientists

2.18

The bulk of the evidence presented to the committee indicated that the

overwhelming majority of scientists actively researching in the area broadly

support the conclusions of the IPCC.[15]

As one witness pointed out:

All of the major national academies of science—from

Australia, the US, the UK, Canada, Germany, India, Russia, China, Italy, Japan

and so on—have declared that climate change is a major global threat.[16]

2.19

The committee heard that medical experts regard climate change as a

major health issue:

Last week one of the world’s top medical journals, the Lancet,

published a report after a year of cooperation with University College London,

declaring that climate change was the greatest threat to global public health

of the 21st century.[17]

2.20

The bulk of the thousands of submissions which the committee received

from the public accept that climate change is happening and urge action.

2.21

Many of the large companies appearing before the committee (either

directly or via industry organisations) employ many scientists, and would be in

a position to express views about the science of climate change. It was notable

that none questioned the science. Examples of statements made are:

The Australian minerals sector is committed to being part of

a comprehensive global response to prevent dangerous climate change.[18]

We accept the general conclusion of the UK government’s Stern

report that the costs of not acting exceed the costs of acting to address

climate change.[19]

I have not heard of anyone within our business or most other

businesses who is against an emissions trading scheme. The end point is agreed

by business.[20]

Rio Tinto supports effective, coordinated action by

governments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions...[21]

2.22

Support was also provided by farmers' organisations:

The Western Australian Farmers Association recognises the

reality of climate change...95

per cent of the climate scientists tell us that humans are causing it and that

we have to do something about it.[22]

Greenhouse gas concentrations and future

temperatures

2.23

The Garnaut Review concluded that stabilisation of greenhouse gas

concentrations at 450 ppm was in Australia's interests. As concentrations are

now around this level, stabilisation will require significant falls in

emissions starting very soon and then reversing some overshooting.

2.24

Most of the scientists assembled by the committee supported the

consensus of global science that 450 ppm was the highest acceptable

stabilisation level.

Just about everyone on the panel has been saying that

achieving a 450 stabilisation by 2050 will give us a 50 per cent probability of

keeping within two degrees...[23]

Dangerous climate change is generally thought to start when

the global average temperature has risen by about two degrees above what it was

in pre-industrial times. In addition, it is generally thought that

stabilisation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere at a 450 parts per million

CO2 equivalent will give rise to a global temperature rise of about

two degrees centigrade above that of pre-industrial times.[24]

2.25

Aiming at 550 ppm CO2e would lead to much greater risks:

...if you stabilise at a 550 parts per million carbon dioxide

equivalent, there is about a 50 per cent chance of Greenland going into this

phase of what could be irreversible melting...If that does shrink significantly,

the potential sea-level rise will be about seven metres.[25]

2.26

There are also scientists who regard the risks of settling for

stabilising at 450 ppm as greater than this. Dr Risbey, a CSIRO

(Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) scientist and researcher

at the centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research, warned:

At 450 parts per million there is a 50 to 90 per cent chance

of exceeding the dangerous threshold of two degrees Celsius...where if we look back to previous

times in earth’s history, we see the ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctic

would break down or start to break down. The worry is that we get to a point

where that breakdown is irreversible...The last time the temperature was two

degrees Celsius warmer than at present,...was about 130,000 years ago. That was

in the peak of the last major interglacial period. At that time sea level was

about five metres higher than present levels...[450 ppm] also gives us about a 10

to 25 per cent probability of exceeding three degrees,...The last time

temperature was three degrees warmer than the present temperature was about

three million years ago, in the Pliocene where sea level was about 25 metres

higher than at present.[26]

2.27

Experts also expressed concern that increasing CO2 was

leading to ocean acidification, which would disrupt the marine food chain by

preventing some organisms forming shells.[27]

Ethical and moral dimensions

2.28

The scientific evidence that taking no action is likely to lead to a

rise in temperatures with serious adverse consequences for future generations

is not alone a case for action if there are some short-term costs to action.

The Stern Review was faced with this issue and captured the essence of

the argument:

...if you care little about future generations you will care

little about climate change, As we have agued that is not a position which has

much foundation in ethics...[28]

2.29

The key question is how policymakers should value the welfare of future

generations. If political leaders are meant to follow 'the will of the people',

or act 'in the public interest', does this include future generations who have

no vote? A related question is the extent to which policymakers in wealthy

countries should be concerned with the welfare of those in poor countries.

2.30

Professor Glenn Albrecht, an environmental philosopher from Murdoch

University, argued:

...it is ethically repugnant to force on innocent and

non-consenting communities, particularly obviously our children and all future

children, a deliberate decision to increase greenhouse gas emissions or a

calculated failure to reduce them to safe levels. We must do the right thing to

avoid imposing a massive and potentially irreversible risk on them. The idea of

irreversibility is something that our ethical systems have not had to deal with

in the past.... The science

is more than sufficient to deliver an ethical response based on risk

minimisation. The issue of irreversible change to the global climate is not one

that humans can dismiss with scepticism or inaction and Australia’s obligation

as a relatively rich, very wealthy, industrialised and well educated country is

to take the lead on greenhouse gas reductions and to set standards that will

deliver a safe and predictable world to future generations.[29]

2.31

An eloquent and moving exposition was provided by Reverend Tim Costello,

Chief Executive Officer of World Vision Australia:

...climate change is no longer [just] an environmental issue;

it is now a humanitarian and a development issue. It is starting to cost lives,

and it will cost many, many more lives... The burden of climate change is going

to fall on the poorest in our own society through higher costs and impact

globally on the poorest nations, which is why World Vision is involved in this

issue. It literally threatens to undo 50 years of development work.

We work with Abdul Mannan, who is 55. He is an elder of the

Dalalkandi on the island of Bhola in Bangladesh. That island has a population

of 2,200. He speaks for many in his community when he says: ‘The place where I

was born lies five kilometres out in the sea. I have already moved my home and

family four times; this is my fifth house. Soon I will have to move again.’ I

have personally seen and listened to these stories...Bangladesh is one of the

poorest and most low-lying coastal areas on earth. Bhola, its biggest island,

is eroding at a phenomenal rate. From a size of 6,400 square kilometres in the

1960s, it is now half its original size. At this rate the entire island of

Bhola will be lost in the next 40 years. So what will become of Bhola’s two

million islanders? Many will be refugees.

...as a child-focused development agency, we are very concerned

about the intergenerational equity of children here and overseas...We in

Australia are enjoying the fruits of our forebears’ thought and work, we have

gratitude for their mobilisation, their sacrifice that saved us from fascism,

and we look forward to our children’s future. But I do not think they will

regard our conduct as fair, looking back, if as a generation they see us as a

selfish generation that left them with problems with no viable solution.[30]

2.32

Reverend Costello's point about the impact on the younger and future

generations was echoed by younger witnesses who appeared before the committee:

The terrible irony of climate change is that those who will

be most affected are the ones that have contributed the least. Also, those who

will be the most affected by climate change have the least ability, at the

present time, to contribute to the decision making and have been consistently

left out of the decision-making processes...Climate change is not a political

issue. It is a human issue. It is about Anna’s grandparents farm in Gunnedah.

It is about the tourism operators up on the Great Barrier Reef and in Kakadu.

It is about the victims of natural disasters all over Australia. It is about

our neighbours in the Pacific that are threatened with their whole homes,

livelihoods and cultures disappearing under the ocean, and about our Torres

Strait that may well go the same way. It is about all we value in Australia and

what we imagine as the cultural icons. It is about our beaches and the heritage

that we want to leave to our children.[31]

The economics of global climate change

2.33

The Stern Review compared the short-term costs of taking action

to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions with the long-term costs of allowing

climate change to take its course.

2.34

Its conclusion was that there was a clear case for action:

Using the results from formal economic models, the review

estimates that if we don't act, the overall costs and risks of climate change

will be equivalent to losing at least 5% of global GDP each year, now and

forever. If a wider range of risks and impacts is taken into account, the

estimates of damage could rise to 20% of GDP or more.

In contrast, the costs of action – reducing greenhouse gas

emissions to avoid the worst impacts of climate change – can be limited to

around 1% of global GDP each year.[32]

2.35

The Garnaut Review looked at similar issues from an Australian

perspective. It concluded:

Mitigation on the basis of 550 [ppm atmospheric concentration

of CO2e] objectives was judged to generate benefits that exceeded

the costs. Mitigation on the basis of 450 was thought to generate larger net

benefits than 550.[33]

Committee view on risk management

2.36

The balance of the evidence discussed above suggests that climate change

is occurring, is driven by anthropogenic factors and is a grave threat to

accustomed ways of life and natural systems. If this view is right, the

calculations above make a virtually unarguable case for taking global action.

2.37

The IPCC makes clear that there is a range of uncertainty around the

projections. But this is not an excuse for inaction.[34]

Prudent risk management would balance the risk of doing nothing when the

climate scientists are right—which would involve very severe and irreversible

damage to human welfare—against the outcome if action is taken unnecessarily,

which would modestly lower economic growth in the short term but mean that

remaining fossil fuel supplies would last longer.

2.38

Even acknowledging the possibility that the majority view on the science

could be totally wrong still leaves a powerful case for a 'no regrets' policy.

Taking action amounts to 'giving the planet the benefit of the doubt'. It is a

sensible insurance policy.

Australia's fair and equitable share of global

emissions targets

2.39

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in an address to the international climate

conference in Bali in 2007, said:

Climate change is the defining challenge of our

generation...one of the greatest moral, economic and environmental challenges of

our age.

2.40

The Government says that Australia's emissions targets are set with

regard to:

the principle that the stabilisation of atmospheric

concentrations of greenhouse gases at around 450 parts per million of carbon

dioxide equivalence or lower is in Australia's national interest.[35]

The Government's unconditional offer

2.41

The White Paper envisaged an unconditional offer of a reduction

of 5 per cent in carbon emissions from 2000 to 2020. A path consistent with

this would see Australian emissions reducing from 109 per cent of 2000 levels

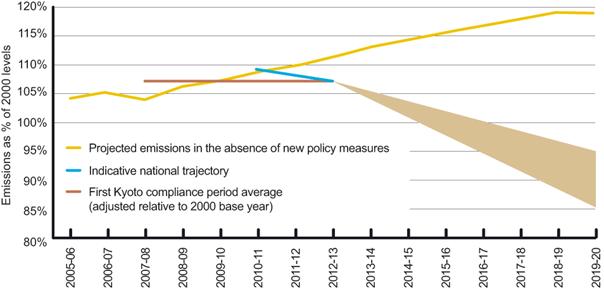

in 2010–11 to 108 per cent in 2011–12, and 107 per cent in 2012–13 (Chart 2.4).

Chart

2.4: CPRS targets

Source: White Paper, p

4-23.

The Government's original conditional offer

2.42

The Government had stated it would go to 15 per cent if there were a

global agreement 'where all major economies commit to substantially restrain

emissions and all developed countries take on comparable reductions to that of

Australia'.[36]

The Government's revised conditional offer

2.43

The Government announced on 4 May that it was raising the conditional

offer it was taking to Copenhagen to a 25 per cent reduction. It explained:

The Government’s new commitment of 25 per cent below 2000

levels by 2020 follows extensive consultation with environment advocates on the

best way to maximise Australia’s contribution to an ambitious global outcome.

It also reflects that international developments since December 2008 have

improved prospects for such an agreement.[37]

2.44

The proposed Australian offer is subject to strict conditions. The main

condition is that there must be an international agreement capable of

stabilising greenhouse gases at 450 ppm or lower by mid-century. The detailed

conditions are quite specific:

1. comprehensive coverage of gases, sources and sectors, with

inclusion of forests (e.g. Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest

Degradation - REDD) and the land sector (including soil carbon initiatives

(e.g. bio char) if scientifically demonstrated) in the agreement;

2. a clear global trajectory, where the sum of all economies’

commitments is consistent with 450 ppm CO2-e or lower, and with a

nominated early deadline year for peak global emissions no later than 2020;

3. advanced economy reductions, in aggregate, of at least 25

per cent below 1990 levels by 2020;

4. major developing economy commitments to slow growth and

then reduce their absolute level of emissions over time, with a collective

reduction of at least 20 per cent below business-as-usual by 2020 and a

nominated peak year for individual major developing economies;

5. global action which mobilises greater financial resources,

including from major developing economies, and results in fully functional

global carbon markets.[38]

2.45

The Department of Climate Change was asked to clarify what was meant by

'fully functioning carbon markets' and replied:

Operationally, it has really meant that Australia would have

access to a broad range of international trading mechanisms. We are not talking

about how every country has to be participating in a particular market; it is

just that there is a deep and liquid market available. That may not require

enormous enhancements, other than the CDM market expanding access to, for

example, European markets et cetera.[39]

2.46

Views differed among witnesses as to whether the conditions were

realistic:

There has been comment around the conditions that have been

set on the 25 per cent target from the government, but in our view they

are a realistic expression of the kind of agreement which would get us to that

450 ppm.[40]

I think that the 25 per cent target is still very low and the

contingencies associated with it are problematic...[41]

...some of those criteria are not helpful, and that the

government should consider revising them.[42]

...the conditions are too stringent.[43]

2.47

Australia's offer is compared to that of other economies in

Table 2.1. Comparing different countries' plans is complicated as they

refer to different base years. For example, the US 2009 Budget proposes a 14

per cent reduction in emissions by 2020 but, as this is from 2005 levels, it

represents only about a return to 1990 levels. Table 1 attempts to express the

various plans on a common 1990 base. It uses United Nations population

projections to express the targets in per capita terms; in some cases

(including Australia) these projections differ from those of national

governments. Another reason the table should only be regarded as indicative

rather than definitive is that different sources give differing estimates of

historical emissions.

Table 2.1: Comparison

of emission reduction targets for 2020

|

Targets and proposals |

% change from 1990 |

% change from 1990 per capita |

per capita emissions (tonnes of CO2e) |

|

Australia |

-3 to -24 |

-30 to -45 |

15 to 12 |

|

European Union |

-20 to -30 |

-25 to -34 |

8 to 7 |

|

United Kingdom |

-34 |

-42 |

7 |

|

US (2009 budget proposal) |

-1 |

-27 |

11 |

|

US (Waxman bill[44]) |

-4 |

-29 |

11 |

|

Canada (Government target) |

+24 |

-8 |

12 |

|

Canada (House bill C-311[45]) |

-25 |

-44 |

7 |

|

Germany |

-40 |

-41 |

9 |

|

Netherlands |

-30 |

-39 |

8 |

|

Norway |

-30 |

-43 |

4 |

|

Switzerland |

-20 to -30 |

-32 to -40 |

4 |

Sources: Secretariat

calculations based on White Paper, p 3-3; Garnaut Report, p 177;

Department of Climate Change Fact Sheet – Emissions, target and global goal;

'Economic cost as an indicator for comparable effort'; 'A new era of responsibility:

renewing America's promise' (US 2009 Budget), p 21; UK Budget 2009: Building

a low-carbon economy- implementing the Climate Change Act 2008. Per capita

percentage changes are calculated from the previous column based on population

projections in United Nations, World Population Prospects and then the

numbers in the final column calculated by applying these per capita percentage

changes to 1990 per capita emissions (including land use change and forestry)

from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change;

http://esa.un.org/unpp.

Arguments for 25 per cent or higher emissions reductions

2.48

As discussed above, the scientific evidence suggests that the global

concentration of greenhouse gases needs to be kept to 450 ppm to avoid the dire

consequences following from increases in average temperatures of over two

degrees. The majority of submitters argued that Australia should therefore make

an offer consistent with its fair share of a global effort to the world

stabilising concentrations at 450 ppm. As Professor Garnaut says:

...to make an unrealistically low offer in the international

negotiations is to negate the prime purpose of our own mitigation, which is to

facilitate the emergence of an effective agreement.[46]

2.49

Australia currently has per capita emissions well above the global

average and many submissions regard it as neither fair nor realistic to expect

the world to accept this remaining the case forever.

2.50

The Garnaut Review assumes the world agrees to eliminate these

differences in per capita emissions (or emissions entitlements) gradually over

the period to 2050 (in a process know as 'contract and converge'). Under this

arrangement, Professor Garnaut's calculation is that Australia's contribution

would be about a 25 per cent reduction in emissions from 1990 levels.[47]

This calculation was not challenged by any witness or submission.

2.51

This conditional target is still Professor Garnaut's preferred position:

...the ETS...would be substantially better than nothing if the

upper limit to emissions reductions were raised to 25 per cent of 2000 levels

by 2020 on condition that other countries had made commitments that added up to

an agreement to hold and to reduce greenhouse gas concentrations in the

atmosphere to 450 parts per million.[48]

2.52

Whether there would be global agreement to this timetable for

convergence has been questioned:

I think the fairest way to do it would be along a contraction

and convergence scenario where you converge at around 2030. I think 2050 is the

sort of thing that the developing world is not going to accept.[49]

So contraction and convergence models as proposed

internationally for well over a decade and most recently by Professor Garnaut’s

review are going to be a key part of the debate. One of the issues, of course, is:

when does convergence happen? When is a fair time at which we all arrive at

some global per capita level of emissions? If you look at it as an entitlement

issue with trading between larger emitters and lower emitters in the early

stages, there is nothing to stop that happening in a very early phase. You do

not need to wait until 2050 to do that, and we may see increasing global pressure

for that to occur.[50]

2.53

Professor Garnaut's approach was endorsed by other witnesses:

Everybody has to be in the boat, as Garnaut has said. But you

cannot get people into the boat in our judgement unless...you have as your

objective an equitable per capita policy that over time delivers some kind of

social equity in terms of per capita emissions. If not, you are in effect

saying to people in India and elsewhere, ‘Your job is to ride your bike and

cook on cow dung for another 50 years while we enjoy getting around in the big

cars.’ We just think that is unsustainable.[51]

2.54

The logic of limiting the Australian offer to a maximum reduction of 15

per cent, as proposed in the White Paper, had been questioned by a

number of witnesses, many of whom argued for the 25 per cent target the

Government subsequently adopted:

...we think it is absolutely critical that Australia puts on

the table at least a 25 per cent target in the upper end of its range as part

of a global effort so it signals that it is actually willing to play its fair

share in an effective global agreement.[52]

...it is terrific that the 25 per cent target is on the

table—it means that Australia need not now go into negotiations as something of

a wrecker...[53]

The main problem with the CPRS is that the targets bear no

relationship to the problem that is trying to be solved...the selection of

targets in the CPRS is entirely disconnected from the scientific problem of

reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[54]

If you look at the ways some of the other countries such as

China and India are positioning themselves, if we are taking a half-arsed

approach in Australia it is going to make a global agreement that much harder.[55]

...the stronger target of 25 per cent does move Australia into

an international climate position that is reasonable to negotiate a successful

outcome for an agreement for 450 ppm or less at the critical negotiations in

Copenhagen later this year.[56]

I think the biggest single problem with the CPRS as announced

is that that conditional agreement—the amount we say we will do if everybody

else joins in—is much below what we need to stabilise the climate. The Garnaut

estimate of a 25 per cent reduction by 2020, I think, was at the very low end

of the reduction that is needed.[57]

2.55

The view of some eminent scientists is that more ambitious targets are

required, in some cases because they interpret the latest scientific results as

indicating that 450 ppm poses unacceptable risks:

The best estimate for the level of global emission reductions

is between 50 and 85 per cent global emission reductions based on the IPCC

assessments by 2050 and an equal per capita approach globally would suggest 90

per cent to 97 per cent emissions reductions for Australia by 2050...if you want to achieve a 450

parts per million CO2 stabilisation target. At 450 parts per million

we still have a 50 per cent risk of exceeding two degrees of warming...In 2020

emission reductions for developed countries should be between 25 per cent and

40 per cent.[58]

If you aim for a target of 450 parts per million, as we said

in our submission that would require at least a 25 per cent 2020 target for

Australia.[59]

...there seems to be a disjunct in what has been put forward in

the Government’s White Paper. The Government emphasised in its White

Paper that it would like to pursue a 450 parts per million CO2-e

outcome and it has put forward an emissions target range that seems to be

inconsistent with achieving that ppm outcome. If the Government wants to

achieve a 450 part million CO2 outcome, the bare minimum to which

Australia can commit is at least 30 per cent.[60]

2.56

These considerations led some environmentalists to regard even the 25

per cent offer as inadequate:

If such a strong agreement were met then we think that

Australia’s contribution should be significantly higher than 25 per cent,

probably in the order of 50 per cent reductions by 2020 if the global deal

resulted in the conditions that have been stipulated by the government being

met for a 25 per cent reduction.[61]

...we really need domestic reduction targets of closer to 40 to

50 per cent by 2020 if we are going to make the contribution that is needed to

meet that level of ambition that the climate science is saying we need.[62]

The vision of young people is that they will be able to live

in a climate that is somewhat similar to the one their parents and their

grandparents lived in. The current targets...will not ensure this...Even at the

upper range of the government’s target, at 25 per cent, there is a 50 per cent

chance of the temperature increase going above two degrees and having

significantly adverse consequences for Australia.[63]

2.57

A study by McKinseys consultants concludes that a 30 per cent target

would be easily affordable for Australia:

A significant reduction in Australian GHG emissions is

achievable—30 percent below 1990 levels by 2020 and 60 percent by 2030 without

major technological breakthroughs or lifestyle changes. These reductions can be

achieved using existing approaches and by deploying mature or rapidly

developing technologies to improve the carbon efficiency of our economy. They

require significant changes to the way we operate in key sectors, for example,

changes in our power mix, but can be achieved without major impact on

consumption patterns or quality of life. Reducing emissions is affordable—with

an average annual gross cost of approximately A$290 per household to reduce

emissions in 2020 to 30 percent below 1990 levels. This compares to an expected

increase in annual household income of over A$20,000 in the same time period.[64]

2.58

Reverend Costello and Dr Pearman questioned the Government's (previous)

conditional target on ethical grounds:

It is not fair because the targets do not represent Australia

taking its fair share of the burden, let alone taking leadership on the issue.[65]

We are a relatively wealthy country and we cannot sit back

and expect all countries to take an equal share in this. All of that together

says to me that we should have a 30 per cent reduction by 2020.[66]

2.59

As noted above, while Australia 'only' emits 1½ per cent of global emissions, it is one of

the world's highest per capita emitters. Furthermore, these calculations

only include emissions in Australia. If Australia were regarded as

'responsible' for the emissions when our exports are used, on the grounds that

we are benefiting from these emissions, Australia would be regarded as an even

higher emitter. World Vision Australia provided an example of these

calculations to bolster the case for Australia adopting a stricter target:

With respect to our coal exports alone, we exported 252

million tonnes of coal last year, and from that you get approximately 740

million tonnes of CO2. If that was a country by itself, its

emissions would rank higher than Canada’s and slightly below Germany’s. If you

add that to our domestic emissions, we would rank slightly below India in terms

of our contribution to the problem.[67]

Arguments that 5 per cent reduction is already tough

2.60

On the other hand, there were some witnesses who regarded even the

unconditional 5 per cent reduction as a tough target:

We do not believe that negative five is a small ask. It is a

big ask for Australian industry. It will require us to reduce emissions by

around 20 per cent on what they otherwise would have been by 2020. So it is not

an insignificant ask and it will have consequences.[68]

...the minus five per cent target, which represents a 25 per

cent reduction in emissions relative to expected trends and a 34 per cent

reduction relative to per capita emissions, is some three to four times

stronger than those proposed by other, wealthier countries such as the USA and

countries of the EU, as measured by an impact on gross national product. AIGN

advocates that Australians shoulder a fair share of the global burden—no more

and no less.[69]

2.61

There were industry witnesses who feared for the future if this target

is pursued – or at least pursued under the CPRS as currently formulated (see

Chapter 4):

...there will be less production, less exports and less

regional employment from both of our [meat and dairy] industries,...[70]

I am absolutely sure that we will see [cement] plants

progressively shutting down prematurely in Australia.[71]

The most immediate and significant impact of increasing the

costs and risks of developing LNG [liquefied natural gas] in Australia is that

it will threaten the industry's competitiveness...[72]

Under the current scheme half of Rio Tinto’s open-cut coal

mines would be likely to close by around 2020.[73]

2.62

Some industry witnesses pointed out that they had already made

significant investments to reduce emissions and that further reductions in

emissions intensity were limited by the laws of physics:

In integrated steel works such as Whyalla or Port Kembla,

direct emissions from the use of carbon as a chemical reductant comprise about

80 per cent of emissions...Both companies’ Australian blast furnaces are

efficient by world standards in their reducing agent consumption. Energy costs

such as coal have always been a focus of the industry and significant work has

been ongoing to reduce these costs over a long period of time. There is very

little ability to further reduce these direct emissions without a breakthrough

in technology.[74]

...since 1990, per tonne of product, we have seen a reduction

of 25 per cent of CO2...The reason for that reduction is primarily

through large technological change.[75]

If you look at the aluminium industry overall over the last

50 years we have reduced direct CO2 emissions by 50 per cent without

a carbon price...[but] in terms of process gains, efficiency gains and business

gains we have reached a plateau.[76]

ALOA’s members have been active in reducing greenhouse gas

emissions from their operations over the last two decades. In fact, the waste

sector is the only sector under the CPRS that has actually recorded reductions

in greenhouse gases in this period. Since 1990, the sector has reduced its

overall emissions by 12.6 per cent.[77]

...60 per cent of lime’s emissions are in fact through the use

of the raw material limestone and do not come from an energy basis...as such,

there is no real opportunity for the lime industry to address that 60 per cent

emissions base.[78]

2.63

The Department of Climate Change's special envoy agreed with the

following characterisation of the argument for the targets in the White

Paper:

...we have got to make up for the fact that at the Kyoto

agreement we were allowed an increase. Some people argue that, therefore, we

have not done our fair share and we need a stronger target. But, in fact, that

makes our trajectory harder to turn around and that is part of the

justification for our target.[79]

Australia's influence in international negotiations

2.64

Some have questioned whether Australia's actions will make a difference

to international agreements:

With only one per cent of world GDP, we are neither prominent

among world nations nor particularly influential within world councils. And

while Australia has many well-qualified scientists, few of these are considered

to be world authorities on climate change. Accordingly, it is pure hubris for

Australia to attempt to take the lead in abatement activity.[80]

2.65

Professor Garnaut, a former ambassador to China, commented:

That position is ignorant of the realities of Australian

diplomacy. I know from my work on the review that views developed in Australia

are very much respected in some of the developing countries that are going to

be very important for the outcome. I have had lengthy discussions at

ministerial level in Indonesia that confirm that. The Indonesian government

sees Australia as a partner in its efforts to do something about climate

change...In China we have access with ideas and we can play a very important role

in helping to define a global regime that helps solve the problem and secures

our interests in the process. I know from close interaction with those three

countries, for a start, that what we say, so long as it is consistent with what

we do, can have a significant influence on the outcome.[81]

2.66

Mr Don Henry, Executive Director of the Australian Conservation

Foundation, believes that Australia can be influential:

Australia can be influential in encouraging key nations, such

as China and the US—and, in our region, Indonesia and India—to strive for a

strong global outcome at Copenhagen...[82]

2.67

He gave as an example of past influence:

Australia played a very strong and very positive role in

getting a global agreement for the reduction of ozone depleting substances.[83]

2.68

Other witnesses argued that Australia should at least try to exert

influence, and setting a good example was an important means of doing so:

It is hard to see a scenario where Australia helps to achieve

a strong global deal by offering to do very little in Australia.[84]

...while we are not a superpower, we are an influential player

in climate change negotiations. Since the EU negotiates as one block, there is

only the EU, the US, Japan, Canada and Australia—they are the five significant

developed countries in this.[85]

Australia's ethical obligations

2.69

There is also an ethical dimension, articulated by environmental

philosopher Professor Albrecht, and supported by other witnesses:

...Australia’s obligation as a relatively rich, very wealthy,

industrialised and well educated country is to take the lead on greenhouse gas

reductions and to set standards that will deliver a safe and predictable world

to future generations...we

in Australia are privileged by virtue of the wealth that we have generated

through our natural resources...That is precisely the kind of society that has to

provide leadership to the rest of the world on all of these major globally

significant issues...[86]

...there is a strong economic and ethical argument for richer

countries such as Australia, the USA and the European Union to take the lead on

reduction commitments.[87]

2.70

Reverend Costello views it as not just a matter of international justice

but inter‑generational justice:

Our generation, which has been the highest spending, worst

saving generation in human history...has had the benefit of not pricing the

carbon. For our generation to actually be locked in the counsel of despair, I

have to say, as an Australian, is a failure of leadership.[88]

Australia's targets in the absence of (adequate)

global agreement

2.71

In the event of no agreement being reached at Copenhagen, as noted

above, the Government has said that Australia's target would be a 5 per cent

reduction from 2000 emissions by 2020.

2.72

One view is that the Australian unconditional target should be the same

as the conditional offer.

If doing something is the right thing to do, it remains the

right thing to do whether or not others are doing it too.[89]

2.73

Professor John Quiggin of the University of Queensland said:

... if the rest of the world does not do anything, we are in

grave straits. The question is really a political one. We have to make an offer

that is sufficient to be in

earnest and good faith but sufficiently short of what we are going to do in an

agreement. We are indicating the weight we place on an international agreement.

That is to some extent a tactical question.[90]

Direct environmental impact of Australia acting

2.74

As Australia is only directly responsible for around 1½ per cent of global greenhouse

emissions, if its actions have absolutely no influence on the rest of the

world, the impact will be correspondingly moderate.

2.75

It is sometimes claimed that Australian actions in these circumstances

would have no impact. A number of witnesses believe this is an

exaggeration:

Australia’s emissions are at least 1.4 to 1.5 per cent of the

global emissions as well, which may sound insignificant, but when you are

dealing with a non-linear system, every bit matters. It is simply not the case

that a relatively small amount of emissions necessarily has no effect on the

climate. That can push us over the limit and over thresholds.[91]

... a 20 per cent cut in Australian emissions by 2020 will cut

projected global emissions by 0.2 per cent.[92]

To a certain extent, the response of the climate system will

be proportional to the emissions and over small ranges. If the emissions turn

out to be 1½ per cent smaller than they would be otherwise because Australia

reduced its emissions, say, to zero, that would have a significant effect on

the climate. I do not like people saying that there will not be any effect.

There will be an effect.[93]

2.76

One witness noted that if every country with smaller emissions than

Australia also took the attitude that it was not worth acting, this would

represent about a third of global emissions that continue to grow.[94]

2.77

Another argument is that a failure at Copenhagen does not end the

process. Environmentalists argued that it remains important for Australia to

set an example.

I think that Australia should lead because as an energy

intensive nation we have a good opportunity to show that a country can become

smarter and more efficient and retain its prosperity by using new energy

sources.[95]

Is Australia acting alone?

2.78

There have been claims that in the absence of a comprehensive global

agreement at Copenhagen that Australia will be acting alone. However, most

witnesses acknowledged this was not the case:

We recognise that Australia is not alone in proposing to take

action to address climate change...[96]

We are not acting alone. The developed world is moving on

this issue. The United States is now taking steps to introduce emission trading

schemes. Japan and New Zealand are doing so and Europe already has one.[97]

...my view is that other countries over time will come on

board, establishing various different ways of pricing carbon within their own economies...The

trend that we have seen is that there are carbon prices out there in the world.

In various places there are voluntary trading schemes, the European scheme of

course, and a couple of regional schemes in the US that are proposed to start

shortly.[98]

Early adoption

2.79

A number of witnesses pointed to advantages in Australia acting before

all other (advanced) economies have agreed to act:

One obvious big benefit would be to avoid having new

investments that later turn out to be inappropriate in a low carbon world.[99]

From a strategic point of view in terms of industry, it is

actually about adopting the practices, growing the skill base and understanding

this process that will be global in my view within less than a decade, and I

think probably less than five years.[100]

If the Australian government and Australian industry embrace

this as an opportunity to play our part, then Australians will benefit from the

jobs and the technology that we will develop. If our national policy settings

focus on resisting change, we will allow other nations to get a head start on

us that we may never recover from.[101]

2.80

It is argued that there is a need to encourage industry restructuring

regardless of whether most countries in the world move quickly or slowly:

I think the aluminium industry is a case in point. The

question is how we develop industry restructuring to assist them to actually

take advantage of Australia’s huge resources of renewable energy. One way we

may fail to do that is if we offer them free trading permits to allow them to

continue to emit.[102]

2.81

On this view, if Australia waits it risks a poor outcome:

...those countries that locked themselves in to a high-carbon

future would be economic losers in the future—because the world will change.[103]

Risks of carbon tariffs if Australia does not act

2.82

Another disadvantage of inaction raised was the risk of facing carbon

tariffs:

The EU in the context of cement is already talking about

imposing border taxes on non-compliant countries, countries which do not sign

up to the general terms available to people. So I think a developed country

which just says, ‘Look, we can’t do this and we won’t do it,’ is also taking a

very substantial risk with its trade.[104]

Economic modelling

2.83

Deciding an appropriate emissions target for Australia requires an

assessment of the economic costs involved, which can be informed by economic

modelling.

Treasury modelling

2.84

Treasury's modelling was released in October 2008, and was described by

the Treasurer and Minister for Climate Change as 'one of the largest and most

complex economic modelling projects ever undertaken in Australia'.[105]

The work drew on a range of models with differing characteristics.[106]

The key conclusions reached are:

...early global action is less expensive than later action;

that a market-based approach allows robust economic growth into the future even

as emissions fall; and that many of Australia’s industries will maintain or

improve their competitiveness under an international agreement...[107]

2.85

The impacts on real income of differing emissions scenarios are

illustrated in Chart 2.5. The key quantitative conclusion is that:

From 2010 to 2050, Australia’s real GNP per capita grows at

an average annual rate of 1.1 per cent in the policy scenarios, compared to 1.2

per cent in the reference scenario.[108]

Chart

2.5: Treasury modelling

Source: Treasury (2008, p

xii).

Criticisms and commentary on the Treasury modelling

Modelling based on outdated

specification of CPRS

2.86

There has been criticism that the Treasury modelling does not refer to

the latest specification of the CPRS. The modelling refers to the ETS envisaged

in the Green Paper and so does not incorporate the changes made in the White

Paper. There have since been further changes to the CPRS announced by the

Government on 4 May.

2.87

Ms Meghan Quinn, who led the Treasury's modelling team, explained:

The main differences between the analysis that was undertaken

in the modelling and the White Paper announcements were around the

emission‑intensive trade-exposed sectors. It is the case that the

arrangements in the white paper were altered such that more transition

assistance was provided to emission intensive trade exposed compared with the Green

Paper proposals.[109]

In general, the aggregate economic costs as a result of the

changes between the Green Paper and the White Paper would not be

expected to be very large at all, but there would be different distributional

implications for both households and for sectors.[110]

2.88

On the specific issue of carbon leakage, the modifications to the scheme

have been in the direction of reducing the imposts on large emitters, so

revised modelling would presumably show smaller leakage effects.

No modelling of alternative schemes

2.89

The Treasury modelling compares the consequences of a few variants of

the CPRS with 'business as usual'. It does not model some of the alternative

schemes (discussed further in Chapter 3) such as a standard carbon tax,

Carmody's consumption-based approach or the 'baseline-and-credit'/'intensity'

approach, or indeed a purer version of cap-and-trade:

...the claim in the White Paper that the CPRS will

achieve abatement at lowest possible cost...is nowhere tested or demonstrated...It

is fundamentally important that the abatement measures we adopt are in fact

least cost, because that will mean we can afford to do more. I would like to

see some explicit modelling to test that claim—that is, to test whether it

really is the least possible cost of abatement.[111]

I would love Treasury to model a consumption based approach.[112]

... the standard benchmark that economists would use to assess

low cost abatement would be to simulate an emissions trading scheme with full

auctioning where that auction revenue is used to lower other distorting

taxes...That simulation has not been done...[113]

2.90

To some extent the models used by Treasury may not be well-suited to

this task. They are able to track through the system the consequences of a

price being established for carbon, but are probably indifferent to the means

by which the price is set. Some modelling at the level of individual companies

may be needed to tease out the differences between baseline-and-credit and

cap-and-trade systems.

No modelling of 'Australia going alone'

2.91

There has been criticism that Treasury has not modelled a 'worst case

scenario' where Australia acts well in advance of competitors:

What we do not see at the moment is an analysis, if you like,

of the risks to Australia of different countries not imposing their own carbon price.[114]

The Treasury did not even model what would happen if

Australia acted on its own.[115]

Given the nature of the collective action problem and the

historical record of slow, partial and fragmented action, it is difficult to

conceive why Treasury did not model and publicly release at least one policy

scenario where comprehensive and coordinated global action fails to develop in

the next decade.[116]

2.92

Treasury has responded that such a scenario would be very unlikely,

especially given that many countries are already implementing an ETS.[117]

Furthermore, Treasury has defended the assumption by arguing that:

To assume otherwise — that is, to presume that the world’s

major emitters will not act at any time to decisively reduce greenhouse gas

emissions — is to presume that the world will gradually succumb to potentially

catastrophic damage to the global environment...The prehistoric peoples of Easter

Island took this path, and paid the price (Collapse, Jared Diamond,

2005). We would do well not to follow their lead. Another logical possibility

is that majority scientific opinion is simply misguided and will turn out to be

a fad. However, to invoke such a possibility as a basis for deciding on public

policy seems to me extraordinarily foolhardy.[118]

2.93

Indeed, Treasury argues that their modelling already covers very

pessimistic scenarios:

...it was judged that having China take on no targets until

2015, despite currently doing quite a lot in the greenhouse gas space to reduce

emissions, we are being more pessimistic than current government policies out

to 2015. Then from 2015, China’s emissions allocation continues to grow until

2030, which was judged to be realistic. Similarly, India does not do anything

at all in the greenhouse gas space until 2020 and then its emissions allocation

continues to grow until 2040. Other developing low income countries do not do

anything until 2025.[119]

2.94

This progressive adoption of carbon pricing was viewed as too optimistic

a programme by some witnesses:

It is going to be an extremely long time before we have a

comprehensive international scheme. Firstly, the negotiations are incredibly

difficult and it is extremely unlikely that countries will sign up on the sort

of timetable that is assumed, for example, in the Treasury modelling

assumptions.[120]

Revised modelling to incorporate the global economic

crisis

2.95

Treasury has also been criticised for not redoing the modelling to use a

baseline incorporating the impact of the global financial crisis. Ms Quinn

explained that they had not been asked by the Government to do such modelling:

We have not been asked to examine in detail the implications

of the GFC [Global Financial Crisis] through the suite of economic models that

we used for the report.[121]

2.96

Moreover, Treasury felt that revising the modelling in the light of the

crisis would not substantially change the results:

...the long-term economic consequences for Australia of placing

a price on emissions is largely unaffected by cyclical variations in output.[122]

...we do not believe that short-term cyclical influences on the

Australian or global economy necessarily have a significant implication for the

medium- and long-term impacts of emissions pricing on the Australian economy.

That still stands true.[123]

2.97

Professor Garnaut provided some support to this view:

...the global financial crisis and recession does not

materially affect the costs of mitigation...[124]

2.98

The deterioration in economic prospects is illustrated by Chart 2.6.

This shows the growth of global real GDP since 1950 (the upper line) and two

forecasts—the current International Monetary Fund projections and that made a

year ago.[125]

(The lower line in the chart shows the path of global CO2 emissions;

the lines diverge when the mid-1970s oil crisis led to increased interest in

energy efficiency.)

Chart

2.6: World real GDP and CO2 emissions

Sources: Chart generated by

Secretariat based on data from IMF, World Economic Outlook; A Maddison, The

World Economy: Historical Statistics, OECD, 2003; World Resources

Institute, CAIT database.

Full employment assumption

2.99

The Treasury modelling has been criticised for applying a full

employment closure rule in the long run. This implies that the lack of impact

on unemployment of introducing an ETS is an assumption rather than a result

of the modelling.

2.100

Mr David Pearce of the Centre for International Economics, who has

reviewed the Treasury modelling, was not critical of this for the long-term

analysis:

I think it is an appropriate closure in the long run, and

these particular models are good at long-run analysis...[126]

2.101

Ms Quinn, who led the Treasury modelling team, explained that they used

three models, one of which has the labour market adjusting rapidly and two of

which have a more gradual adjustment. Models assuming a rapid adjustment in

employment reflect a slowing in output in lower real wage growth rather than a

rise in unemployment.[127]

Lack of modelling the transition

2.102

The Treasury modelling focuses on the long-run consequences; on the

position of the economy once it has settled down into a new, lower-emission,

equilibrium. It has less to say about the impact during the adjustment phase:

The economic modelling solves each year of the scenario, so

there are results for 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013...Chapter 2 of the report

outlines some of the limitations of the economic models that we have available

to us. They do not necessarily capture all the transition elements and in some

cases they are too fast in terms of their adjustment. They are typically, in

our judgement, better for looking at after the first few years...What is

important to look at for these economic models for these types of questions are

averages and time frames.[128]

2.103

Mrs Heather Ridout of the Australian Industry Group emphasised to the

committee that more attention should be paid to the difficulties of transition:

... some people think that we will get in the Tardis booth in

2010 and get out in 2020 and everything will be hunky-dory... The Treasury’s

modelling acknowledged that they could not fully capture those transition

costs...I go back to what I said after the Treasury modelling came out: it is not

easy to capture the transition costs and we are not in a Dr Who Tardis box.[129]

2.104

This aspect of the modelling was criticised by Dr Brian Fisher, director

of Concept Economics:

...you can see that there are no transaction costs and there

are no transition costs represented in that modelling...It simply is not

realistic.[130]

2.105

Dr Fisher is therefore critical of the modest costs of introducing a

carbon price in the Treasury modelling:

...that is what every piece of modelling will say to you if you

do it in this particular way, that does not pick up the costs of taking people

in regional Australia, getting them better jobs, putting them someplace else,

retraining them and dealing with the fact that our energy intensive emissions

associated with the aluminium industry, the alumina refining industry and so on

effectively are no longer competitive in the world.[131]

2.106

Mr Pearce commented:

The

transitional analysis is not easy to do. The frameworks that we use generally

take a long-term perspective, but it can be addressed. It is important to do so

and to walk in with our eyes open about what the transitional consequences are.

The fact that there are transitional costs is not a reason not to proceed with

the policy, because mitigation has costs but those costs will hopefully be

offset by benefits in the future.[132]

Lack of regional or more disaggregated modelling

2.107

The Treasury modellers presented results disaggregated by state and by

industry. There was a call that Treasury should have done modelling at a finer

degree of disaggregation:

We had hoped the Treasury modelling exercise might have

addressed the impact of higher energy prices on a sectoral, firm or regional

level.[133]

We were hoping for some more detail in that information

regarding the impact on particular industry segments across each of the states

and so on.[134]

I believe there needs to be more extensive modelling so that

we can assess the effects of an ETS scheme...I think drilling down into the

detail is a component that I see missing so far...[135]

2.108

Frontier Economics prepared a report for the NSW Government, which

contained results at a regional level. Unfortunately the NSW Government has not

publicly released this report, although it has been discussed in the media.

2.109

Ms Quinn doubted whether modelling at a regional level would be

sufficiently robust to aid in analysis of the CPRS:

...we did not use the regional component of the MMRF [Monash

Multi Regional Forecasting] model in the Treasury modelling because we did not

think it was robust enough. The results coming out of it were nonsensical... Unfortunately

the data sets available make it very difficult to do robust analysis at a

quantitative level for regional economies.[136]

2.110

Questions were also asked about reconciling Treasury's modelling results

with claims of imminent job losses by individual companies. Ms Quinn responded:

Our economic modelling does suggest resources will move

between sectors. You have had people say that they will be adversely affected

and you have had people say that they will benefit from this scheme. What

happens is that there is a shift between industries and that means a movement

of capital and labour between industries in response to relative price.[137]

Lack of peer review and transparency

2.111

Treasury have been criticised for not making more detailed results

public and having their modelling subject to the kind of 'peer review' that

would apply to an academic paper published in a leading journal.

2.112

Mr Pearce cast a critical eye over Treasury's work. He said:

I agree that those models themselves are sound. However, I

believe in any modelling analysis it is very important to do a lot of

sensitivity analysis to understand the importance of particular parameter

choices within those models. That is one of the things that has not been done

yet.[138]

2.113

A useful check on Treasury's use of the models was that Frontier

Economics, as part of their regional analysis, replicated some of the Treasury

modelling:

The modelling results that we produced on one scenario—the

one that has been reported most widely—is in fact the same modelling result, as

far as we can tell, as that produced by the Treasury.[139]

2.114

The Senate Select Committee on Fuel and Energy commissioned a review

from Concept Economics of the Treasury modelling. The author, Dr Brian Fisher,

questioned some assumptions in the modelling which he thought 'likely to result

in the Treasury modelling seriously underestimating the economy-wide and

sectoral challenges associated with particular emissions reductions targets'.[140]

2.115

The Select Committee on Fuel and Energy sought unrestricted access to

all the model codes and databases used in the Treasury modelling but it was not

provided. The Government referred to the extensive documentation that had been

made publicly available and claimed contractual arrangements with external

consultants limited the additional information that could be provided.[141]

Inadequate modelling of consequences for the rural sector

2.116

Agricultural emissions are not included in the CPRS, at least in the

initial years of its operations. However, this does not mean that the rural

sector is unaffected. Farmers will face higher prices for electricity. They may

also face lower prices for the animals and products they sell to food

manufacturers as the manufacturers try to 'pass back' some of the additional

cost they face in having to buy permits.

2.117

The committee heard claims that these impacts have not been properly

addressed by the Treasury and Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource

Economics (ABARE) modelling:

As to most of the general equilibrium models that operate at

the moment...they do not have the linkage back in terms of cost.[142]

CHAIR—But none of the modelling that I have read

through seems to take into account the impact on farm of the CPRS on the

processing sector of agriculture... Mr Keogh—No, and the difficulty is

that you cannot do that modelling until you know with some degree of certainty

what proportion of the processing sector exceeds the 25 kilotonne threshold and

therefore is required to pay a price for their emissions.[143]

2.118

Ms Quinn believed these effects were adequately reflected in the

modelling:

My understanding is that this analysis is quite comprehensive

and...looks at the implications of, and has much more detail on, disaggregating

the meat processing and dairy processing from the input side, so that you can

get a feel for what is going to happen through the process chain in

agriculture.[144]

Can I clarify that the computational general equilibrium

models used do link together agriculture and processing industries back and

forward, just as occurs in the economy.[145]

2.119

There were more general requests for more detailed modelling of the

effects on the farm sector:

The government has done no sectoral modelling around

agriculture, other than the broad general equilibrium model.[146]

Recommendation 1

2.120

The committee notes that the Treasury modelling was conducted in

economic circumstances that were markedly different to those in which the

legislation is proposed to now be introduced. Since the modelling was conducted

the global financial crisis has led to a marked deterioration in the short-term

economic outlook.

Whilst the CPRS package has been revised on two occasions,

the modelling continues to fail to take into account the impact of these

changed economic circumstances. The committee considers the modelling

undertaken by Treasury to be inadequate and recommends that the Government

direct Treasury to undertake further modelling. The further modelling should:

-

consider in detail the short-term adjustment costs;

-

respond to criticisms made of Treasury's initial modelling

including:

-

taking into account the deterioration of the Australian economy

-

the likely effect of the CPRS upon jobs and upon the environment

-

the absence of any modelling of the impact of the CPRS on

regional Australia; and

-

model other types of schemes that have been proposed as alternatives

to CPRS, including:

-

a conventional baseline-and-credit scheme

-

an intensity model

-

a carbon tax

-

a consumption-based carbon tax, and

-

the McKibbin hybrid approach.

The Garnaut Review modelling

2.121

The Garnaut Review modelling was broader than the Treasury modelling,

as it also considered some of the costs of not addressing climate

change. In particular it covered impacts on primary production, human health,

infrastructure, tropical cyclones and international trade.[147]

By 2100 real GNP, GDP, consumption and wages are 6-10 per cent lower than they

otherwise would be as a result of climate change and the impact is continuing

to grow.[148]

Adding in the increased risk of absolutely catastrophic outcomes, and the

non-market impacts, would raise these estimates considerably. Garnaut notes

that other modelling has shown that costs in the 22nd century will

be dramatically higher—perhaps approaching 70 per cent of global GDP by 2300.[149]

2.122

Concerning the costs of restricting emissions, the Garnaut modelling

closely agrees with the results of the Treasury modelling, about a 0.1 per cent

a year reduction in economic growth.

2.123

The net costs of mitigation become negative by 2060 (i.e. GDP growth is stronger with mitigation than under business‑as‑usual). Agriculture is

the big winner (as crops are more sensitive to temperature than manufacturing)

but by the latter half of the century mining also is doing better.

2.124

The modelling also throws some light on the difference between aiming to

stabilise at 450 and 550 ppm. The more ambitious target costs an extra 0.7–0.9

per cent of GDP (in net present value terms). Given the environmental benefits

and the insurance value of reducing the risk of catastrophic impacts, Garnaut:

...judges that it is worth paying less than an additional 1 per

cent of GNP as a premium in order to achieve a 450 result.[150]

2.125

Garnaut's conclusion is that:

The costs of well-designed mitigation, substantial as they

are, would not end economic growth in Australia, its developing country

neighbours, or the global economy. Unmitigated climate change probably would.[151]

2.126

He also comments that modelling of large changes to the structure of the

economy is likely to overstate the costs of these changes:

Experience shows that once consumers and producers have

accepted the inevitability of change, and face predictable incentive

structures, they will alter their behaviour to account for the new conditions

more efficiently and effectively than previously predicted. This experience

suggests that economic models are more likely to underestimate the benefits or

overestimate the costs of changes in economic conditions, so long as the change

is to stable institutional arrangements and predictable incentives. This bias

may be further exacerbated by lack of data about the full costs of climate

change impacts and a corresponding downward bias in the estimated benefits of

avoided climate change.[152]

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics

(ABARE) modelling

2.127