Chapter 4 - The Timor Gap (Zone of Co-operation) Treaty

Introduction

4.1

The Timor Gap Treaty is a unique arrangement for

enabling petroleum exploration and exploitation in offshore areas, subject to competing

claims by two countries,

and for the sharing of the benefits between those countries.[1]

4.2

The Treaty between Australia and Indonesia was

signed in December 1989, and deals provisionally with the gap in the seabed

area not covered by the 1972 Seabed Agreement between Australia and Indonesia; that

is, the seabed area between Australia and East Timor.

When the 1972 seabed agreement was negotiated, East

Timor was not part of Indonesia and, as a result, a ‘gap’ was left between the eastern and western

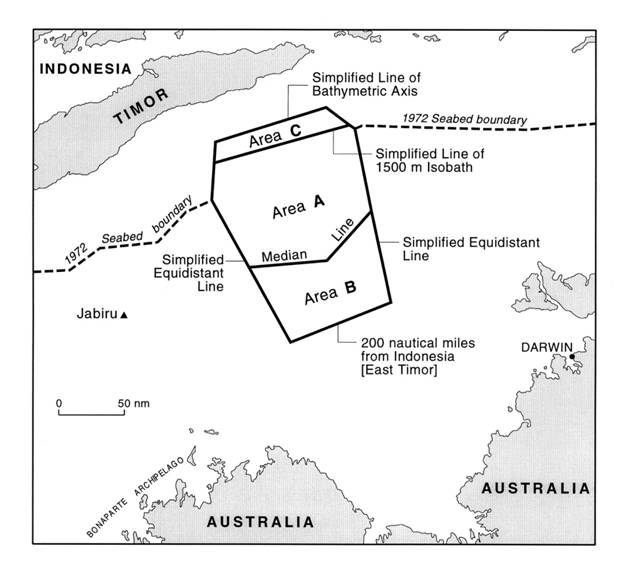

parts of the Australia-Indonesia seabed boundary: the ‘Timor Gap’. The Treaty

establishes a Zone of Co-operation comprising three distinct areas—Areas A, B

and C. It creates a regime that allows for the exploration and development of

hydrocarbon resources in the Zone. Area B lies at the southern end of the Zone

and is administered by Australia. Area C lies at the northern end of the Zone and was administered

by Indonesia. Area A is the

largest area and lies in the centre of the Zone. The rights and

responsibilities of Australia

and Indonesia in relation to

Area A were exercised by a Ministerial Council and a Joint Authority

established by the Treaty. The Joint Authority is responsible to the

Ministerial Council.[2]

4.3

The Treaty was

entered into for an initial term of 40 years, with provision being made for

successive terms of 20 years, unless by the end of each term, including the

initial term of 40 years, the contracting states should have concluded an

agreement on the permanent delimitation of the continental shelf between

Australia and East Timor—a seabed treaty. [3]

4.4

The Treaty was challenged by Portugal in the International Court of

Justice when it entered into effect in 1991 on the grounds that it violated the

rights of the people of East Timor to self-determination and violated Portugal’s rights as the administering power of East

Timor. As Indonesia declined to consent to the jurisdiction of the Court, the Court was

unable to adjudicate the matter.[4]

4.5

The Treaty arrangements proved to be beneficial

to both Indonesia and Australia. Within the Zone of Co-operation,

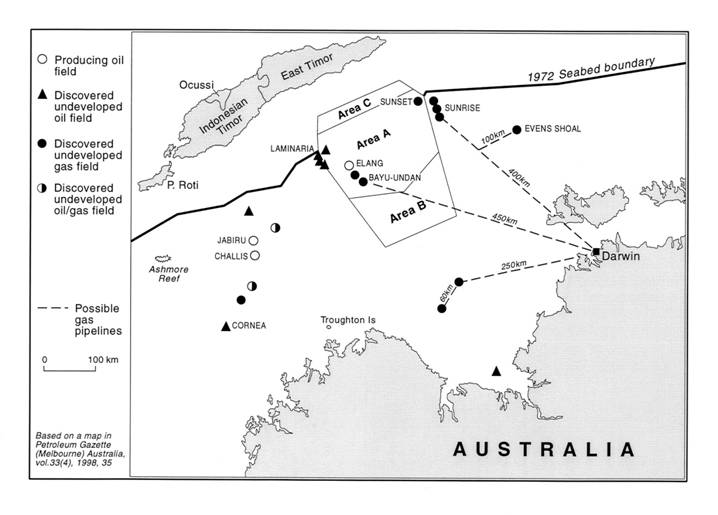

an exploration program, which involved the drilling of 42 wells, resulted in

the discovery of hydrocarbons in 36 of the wells and the identification in Area A of about 400

million barrels of condensate (a light oil) and LPG (liquid petroleum gas) and

three trillion cubic feet of gas. These resources have been discovered in some

medium to small oilfields, including at Elang-Kakatua and Jahal, and some large

gas fields at Bayu-Undan and Sunrise Troubadour.[5]

4.6

At each

Ministerial Council, Ministers from Indonesia and Australia gave reports on

activities in Area C and Area B respectively. To date, there has been no

exploration carried out in Area C and it is not seen as particularly

prospective, both because of its depth and the geology of the area.[6]

4.7

In Area B,

the Australian area of jurisdiction, there has been some exploration, both

seismic and drilling of wells, but to date no hydrocarbons have been found.[7]

4.8

In Area A, the

Elang-Kakatua field began commercial production in mid-1998 with production to

November 1999 valued around $A250 million, returning to each contracting

state around $5 million in revenues from the production sharing

arrangements. East Timor received its first royalty

payment from the Timor Gap, worth over US$3 million, on 18 October

2000.[8]

The revenue came from oil lifted from the Elang-Kakatua field, the only active oil

field in the Timor Sea. The figure represented half of the revenues collected

from production sharing between 25 October 1999 and 25 September

2000.

4.9

The cumulative

employment figure for Area A of the Zone from the commencement of

operations in 1991 to November 1999 was around 124,000 man-days for Australians

and 80,000 man-days for Indonesians.[9]

4.10

The Treaty and associated arrangements attracted exploration and development

to the Zone of Co-operation with significant industry investment. The Committee

was told the Treaty provisions had withstood the test of time over the period

1991 to November 1999, and there had been no need to amend the Treaty, the

petroleum mining code or the model production sharing contract. From time to

time, various issues arose and were successfully resolved through the Joint

Authority and Ministerial Council.[10]

4.11

During the interim phase before independence,

the United Nations transitional administration (UNTAET), has overall authority

for the administration of East Timor and consequently, an important role to

play in respect of continuity of the Timor Gap Treaty regime.[11]

Indonesia’s

interest

4.12

The Zone of

Co-operation established by the Timor Gap Treaty was intended to be referable only

to the coast of East Timor and the opposite coastline of Australia. There is a

question whether Indonesia has any remaining legal interest in the location of

the boundaries of the Zone following the movement of East Timor out of Indonesian

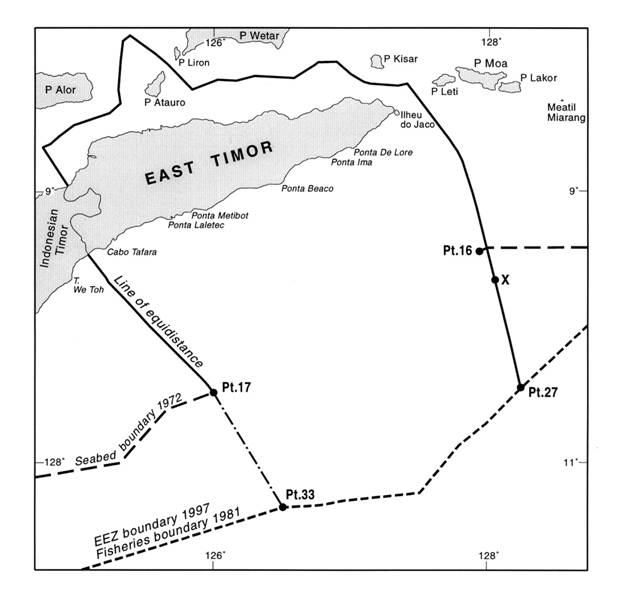

sovereignty. In this respect, the focus would be on points A16 and A17,

identified in the 1972 seabed boundary agreement.[12] These

are at the eastern and western extremities of the Timor Gap Zone of

Co-operation (see map of the Zone of Co-operation).[13] Points

A16 and A17 (at 9°28’S and 127°56’E, and 10°28’S and 126°E) are the points at

which the Australia-Indonesia seabed boundary joins the Zone of Co-operation,

on each side. It is those two points, termed tripoints, where the

interests of Australia, independent East Timor and Indonesia would meet, and it

is in the location of those points where Indonesia might have a continuing

interest.[14]

The 1972 seabed treaty noted in Article 3 that the lines connecting points 15

and 16, and points 17 and 18, indicated the direction of the boundary and that

negotiations with other governments that claimed sovereign rights to the seabed

(then Portugal, now East Timor) might require adjustments to points 16 and 17.[15]

4.13

Since the 1972

seabed boundary agreement was established, Indonesia has twice accepted those

points as being reasonable, and in the proper location: first, in the

negotiation of the Timor Gap Treaty itself; and, second, in the 1997 agreement

between Australia and Indonesia establishing an exclusive economic zone boundary

and certain seabed boundaries.[16]

4.14

The agreement of

the Indonesian Government is not required for any changes to the Treaty. There are

details which required attention in terms of Indonesian disengagement but,

Indonesia, as representatives of Indonesia have said publicly, has no role in

its future.[17]

4.15

The two tripoints

A16 and A17 are closer to the island of Timor than the mid-points between the

island and Australia. In 1972, Indonesia accepted the Australian contention

that the seabed boundary between the two countries should lie between the

mid-line and the deepest part of the seabed, the Timor Trough.[18]

Negotiations on a seabed treaty with Portugal failed at that time because

Portugal argued for a boundary along the mid-line between Australia and Portuguese

Timor.[19]

If, in a new treaty, Australia were to concede to East Timor a seabed boundary

along the mid-line, Indonesia might be prompted to seek re-negotiation of its

seabed boundary with Australia.[20] Dr Gillian

Triggs, Associate Dean of the University of Melbourne’s Law Faculty, has

commented: ‘There is no doubt Indonesia will feel quite aggrieved if we have

unequal boundaries in certain areas with Indonesia and we suddenly blow the

boundary out and make a more equidistant one in relation to East Timor’.[21] The border alongside the Zone

of Co-operation is a sensitive issue as several major gas and oil deposits lie

just outside Indonesian territory in Australian waters including the 140,000

barrels-per-day Laminaria field.

4.16

However, it should also be noted that: (a) the

seabed boundary treaty stands in perpetuity; (b) that amendment to the 1972

treaty can only be made by agreement of both parties; and (c) a party can only

withdraw from the treaty with the agreement of the other party. As a

consequence, it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, for Indonesia

to reopen the question of the seabed boundaries outside the Timor Gap (aside

from the possibility of adjustment of tripoints A16 and A17). Any unilateral

denunciation by Indonesia would be rejected by the International Court of

Justice.

4.17

In August 1999, Australia defined the

south-western maritime boundary for the Interfet operational area in East Timor

by drawing a line perpendicular to the general direction of the coastline

starting from the mouth of the Massin River, which separates West and East

Timor. A similar projection of East Timor’s maritime claims, if adopted as part

of settlement of Timor Gap maritime boundaries, would bring the

Laminaria/Corallina fields, which are just outside the current western boundary

of the Zone of Co-operation, within the sovereignty of East Timor.[22]

4.18

According to some experts, the line on the

eastern side of the Gap seems to have been drawn from the eastern tip of the

East Timor mainland, not the small outlying island of Jaco. If the eastern

boundary were rectified to take this into account, the adjustment would put

more of the Sunrise-Troubadour gas fields, found by Woodside Petroleum and

partners, into the Timor Gap (north of the median line) rather than the Australian

exclusive zone. Under the Treaty, this group of gas reservoirs extends about 20

per cent under the shared zone.[23]

1997

Delimitation Treaty

4.19

The March 1997

Delimitation Treaty between Indonesia and Australia was a treaty which

completed the negotiation of maritime boundaries between Australia and

Indonesia. It has not yet been ratified, or entered into force. The Treaty

delimited the exclusive economic zone boundary between East Timor and

Australia. The Australian view is that the 1997 treaty remains in a

satisfactory form between Indonesia and Australia, but it will have to be

amended to reflect the fact that East Timor is no longer under Indonesian

sovereignty.[24]

On 2 September 1997,

Portugal lodged a challenge to the Treaty, which was circulated at the United

Nations. The protest document disputed the right of the Treaty to set a

water-column line running through the Timor Gap, on the same grounds as

Portugal’s earlier challenge to the Timor Gap Treaty.[25]

Administrative arrangements in

the transitional period

4.20

Following the

30 August 1999 popular consultation, the Australian Government developed

and implemented a strategy aimed at ensuring the smooth transition of the

Treaty. Officers from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the

Attorney-General’s department, and the Department of Industry, Science and

Resources liaised with officials from the United Nations and East Timorese

representatives and consulted the petroleum industry to enable a smooth

transition of operations under the Treaty. Transition arrangements needed to

cover issues such as:

- the location of the

headquarters of the Joint Authority, originally in Jakarta;

- appointment by the United

Nations of appropriate representatives on the Ministerial Council and of people

to participate on the Joint Authority; and

- the status of the existing

production sharing contracts as well as the existing regulations, directions

and other matters resolved to date by the Ministerial Council and the Joint

Authority.[26]

4.21

In discussions

with the Australian Government, East Timorese representatives, particularly Mr

Gusmão, Dr Ramos-Horta, and the East Timorese spokesman on Timor Gap matters,

Dr Alkatiri, confirmed their willingness to see the Treaty continue in its

current form. The United Nations indicated a similar view.[27]

Bayu-Undan liquids recovery and

gas recycle project

4.22

The Darwin Area Manager of Phillips Oil Company Australia, Mr James Godlove,

told the Committee on 8 September 1999:

Phillips, through various subsidiary companies, have major

economic interests relating to petroleum development within area A of the Zone

of Co-operation. We have already made very significant investments. With our

co-venturers we are nearing a decision to approve a $US1.4 billion budget for

the construction and operation of the Bayu-Undan Liquids Recovery and Gas

Recycle Project ... To provide a secure environment for these

investments and to realise the full potential of petroleum resources in this

area, it is vital that the treaty be sustained and that key transitional issues

accompanying any change in the sovereign status of East Timor be managed

smoothly.[28]

Mr Godlove also said:

... the present commercial and fiscal terms of the treaty must be

maintained. These include provisions relating to production sharing and cost

recovery of capital and operating expenses. Furthermore, any tax regime

established in East Timor should be no more onerous than the Indonesian regime

being replaced. These provisions establish the basis for petroleum development

in the zone of cooperation and any adverse change in these provisions could

have a profound effect on our project economics.[29]

Speaking at a seminar in Canberra on 14 June

2000, Mr Godlove said:

The major unresolved matter that does need to be addressed

expeditiously is the lack of a defined fiscal regime in the terms of the Treaty

regarding gas exported from the Zone of Co-operation. An agreement on that

matter would have significant economic benefits to both East Timor and

Australia.[30]

4.23

Mr Keith Spence, Woodside Energy Limited, told

the Committee on 20 July 1999 that his company was concerned to preserve the stability and elimination

of sovereign risk that the current Treaty regime

provided.[31]

Woodside expected to be among the suppliers to major new customers in the

region, based on substantial reserves in the Sunrise-Troubadour field that

extends into the Zone of Co-operation. Sunrise-Troubadour could probably

produce ten trillion cubic feet of gas, as opposed to three to four trillion

cubic feet from Bayu-Undan.[32]

4.24

A consortium led

by Phillips Petroleum announced on 26 October 1999 that it would proceed with

the first stage of the development of the Bayu-Undan field, in Area A of the

Zone of Co-operation. This would involve the extraction of gas, stripping of

the condensate and LPG liquids from the gas, and re-injection of the dry gas.

The consortium would invest capital expenditure of about $US1.4 billion. The

project would provide significant employment opportunities to Australians and

East Timorese. Phillips indicated that revenues of ‘many tens of

millions of US dollars’ a year were likely to flow to Australia and East Timor.[33] In the press

release announcing its decision to proceed with Bayu-Undan, Phillips referred

to substantive and encouraging discussions with all relevant parties involved

in East Timor’s transition to independence.[34] They had received a letter signed by

Mr Gusmão, Dr Ramos Horta and Mr Alkatiri saying they would honour Timor Gap

petroleum zone arrangements.[35]

4.25

Santos Ltd, which holds 11.8 per cent

of the Bayu-Undan gas project, confirmed on 18 November 1999 that it had opted

to participate in the project.[36]

Santos was the last of the six partners in the project to publicly

confirm its continuing participation, opening the way for the development plan

to be submitted to the Joint Authority for final approval.[37] The project was

expected to produce 110,000 barrels of condensate and LPG from 2004. The second

stage of the project proposed construction of a gas pipeline to a LNG

production facility in Darwin, which would then sell the product to overseas

customers.[38]

4.26

On 28 February 2000, the United Nations

Transitional Administrator in East Timor, Mr Vieira de Mello, and the

Australian Minister for Industry, Science and Resources, Senator Nick Minchin,

announced that approval had been given by the Joint Authority for the first

phase of the Bayu-Undan petroleum project in Area A of the Timor Gap Zone of

Co-operation.[39]

4.27

It is not possible

to predict with certainty the likely revenues to flow to East Timor and

Australia from the Bayu-Undan project. The actual revenues received will depend

on highly variable oil and gas prices received from the project. Production

rates tend to peak in the first few years of a liquids project and then

decline, while gas projects have a relatively flat production profile related

to the requirements of their gas customers and the timing with which the

various phases of the project come on stream.[40]

4.28

Given

uncertainties associated with price and different start-up dates for the phases

of the project, the prospective income stream is in the order of several tens

of millions of dollars annually, for over a decade from 2003. That would

represent a significant proportion of East Timorese GDP.[41] In addition, Treaty-related

activities would provide important employment and training opportunities for

East Timorese across a range of disciplines from engineering to administration.[42]

4.29

In an interview on

the ABC radio program Asia Pacific broadcast on 10 October 2000, Mr

Peter Galbraith, Member for Political Affairs of the East Timor Transitional

Cabinet, said:

These resources are

enormously important to East Timor. By the end of the decade it could mean

between $US100 million and $US200 million for East Timor, depending on how

these negotiations turn out, and for a country whose annual budget is just

$US45 million that makes all the difference ... The resources of the Timor Sea

could make the difference between having to choose between children’s health

and children’s education to being able to do both.

The

transition from Indonesia to East Timor

4.30

Concerning the treaty obligations of new states, the Attorney-General’s

Department quoted an authoritative statement by Lord McNair:

Newly established States

which do not result from a political dismemberment and cannot fairly be said to

involve political continuity with any predecessor, start with a clean slate in

the matter of treaty obligations...[43]

4.31

When one state or

one part of a state separates from an existing state there arises the question

of whether that new state takes on the treaty obligations of the previous state

or whether there is what is called a ‘clean slate’. In other words, can they

start again and choose those treaty obligations of the former state which they

will take on later? In these circumstances, there are two relevant conventions,[44] but as

Australia is not a party to them, customary international law becomes the

basis. In terms of customary international law, if East Timor had become

immediately independent from Indonesia without an interim period of United

Nations administration, it would have been subject to the clean slate doctrine;

it would not have been forced to take on the treaty obligations of Indonesia

but, nevertheless, could have chosen those obligations which it did want to

take on.[45]

4.32

However, East

Timor was not the usual scenario. Indonesia no longer exercised sovereignty.

The view was that Portugal should not re-assert its sovereignty, even in the

most technical sense, a view shared by Portugal. But, as no new independent

East Timorese state had emerged, Australia faced the situation of there being

no state with which to treat. In the absence of such a state, with whom could

Australia enter into agreement to secure the continued operation of the Treaty?[46]

4.33

The answer

involved a new precedent in international law. Under Security Council

resolution 1272, which set up the United Nations Transitional Administration in

East Timor, UNTAET, a transitional period of some two to three years was

established for East Timorese transition to independence. Under paragraph 35 of

the United Nations Secretary-General’s report, which was incorporated by

specific reference into the Security Council resolution, the United Nations

would ‘conclude such international agreements with states and international

organisations as may be necessary for the carrying out of the functions of

UNTAET in East Timor’. Resolution 1272 stressed the need for UNTAET to consult

and co-operate closely with the East Timorese people in order to carry out its

mandate, including the question of keeping the Treaty on foot.[47] This gave UNTAET a wide treaty making power,

providing more than sufficient basis for the United Nations to enter into an

agreement with Australia to confirm the continued operation of the Treaty. In

effect, the United Nations, through UNTAET, would be Australia’s treaty party

until the independent state of East Timor emerged.[48]

4.34

A workshop on the

Treaty of interested parties was held in Dili, 17–19 January 2000, attended by

about 50 geologists, lawyers, engineers, economists and other experts from

Australia, the United Nations, East Timor, Portugal and Mozambique. Woodside

Petroleum and Phillips Petroleum were represented at the workshop. Dr José

Ramos-Horta and other members of the East Timor National Consultative Council

attended. Mr James Godlove, of Phillips Petroleum, said following the workshop,

‘There was strong expressions of support for continuation of the Treaty and any

continuation of the terms of the Treaty’.[49]

4.35

When the Committee

took evidence in November 1999, the Government was involved in discussions with

the United Nations on the detail of the arrangements for the transition of the

Treaty. Some adjustments had to be made to the Treaty, primarily to the

arrangements for the Joint Authority which managed the rights and

responsibilities under the Treaty on a day to day basis.[50] While working to ensure the Treaty’s future,

there was the need to deal in an orderly way with the Treaty’s past. Australian

officials had discussions at a technical level within the Joint Authority

concerning the process of Indonesian disengagement from the Treaty. Indonesian

representatives, including the Ambassador at Large for the Law of the Sea and

Maritime Affairs, Hasjim Djalal, expressed the view that Indonesia would no

longer have a role to play in the Treaty. This view was shared by the

Australian Government, and after the separation of East Timor from Indonesia

was completed, detailed discussions commenced with Indonesia on the mechanics

of Indonesian disengagement.[51]

4.36

On 10 February

2000, diplomatic notes were exchanged in Dili by the United Nations

Transitional Administrator, Mr Vieira de Mello, and Australia’s Representative

in East Timor, Mr James Batley, to give effect to a new agreement, whereby

UNTAET replaced Indonesia as Australia’s partner in the Treaty. Under the

agreement, which was negotiated in close consultation with East Timorese

representatives, the terms of the Treaty would continue to apply. In talks in

Jakarta preceding the agreement, Indonesian representatives had agreed that

following the separation of East Timor from Indonesia, the area covered by the

Treaty was now outside Indonesia’s jurisdiction and that the Treaty ceased to

be in force as between Australia and Indonesia when Indonesian authority over

East Timor transferred to the United Nations.[52] The Australian Timor Gap Treaty

(Transitional Arrangements) Act 2000 formalised this position.[53]

4.37

Under the Treaty,

the industry already had provided significant employment opportunities: of the

number of man days, 124,000 were Australian and 80,000 were Indonesian. Those

figures covered all activities related to exploration as well as production in

the Zone, to October 1999. The employment included labouring jobs; technical

jobs such as in engineering; and vocational jobs such as welders, electricians,

engineers and geophysicists.[54] For the Indonesian share of

employment to be transferred to the East Timorese, there was need to assist

them in obtaining the skills and the skill levels needed to take up the

available employment opportunities. Australia undertook to attempt to make

those same opportunities available to East Timorese workers. A World Bank

survey was undertaken of the training needs of the East Timorese population, to

help them participate in an independent state. Part of that was to identify the

kinds of skills that they would need if they were to take advantage of the

opportunities presented under the Treaty.[55]

4.38

Responsibility

under the Treaty for determining employment shares primarily rested with the

production sharing contractors, with encouragement through the Joint Authority

and the Ministerial Council. Under the terms of their contract, the production

sharing contractors had the objective of giving preference to employing

Australian and Indonesian (now East Timorese) nationals in equal numbers,

subject to the requirement of good oilfield practice. The imbalance had been in

Australia’s favour but was gradually moving towards Indonesia’s favour with

employment on the Modec venture to develop Elang-Kakatua.[56] Both contractors and sub-contractors were bound

by these employment requirements. Contractors required competent employees with

requisite skills who could observe good oil field practice and safety at all

times. As few East Timorese had such skills, training was required to enable

them to attain the necessary skills to participate in the oil industry.[57] The Committee was told:

We have also been holding

discussions with the production sharing contractors in terms of whether there

are opportunities for them to provide training and work experience for East

Timorese. As we work our way through the Joint Authority and the workshop which

we will be having in December, and as we continue with those sorts of

discussions through the Ministerial Council and through the Joint Authority, we

would be hoping to get an indication from the East Timorese of where their

priorities lie and where the industry can fit in with aid agencies - whether

they be AusAID, World Bank, Asian Development Bank or the other aid and service

providers.[58]

4.39

On 4 October 2000, Minister for Resources

Senator Nick Minchin announced two initiatives under the auspices of the Timor

Gap Zone of Cooperation Ministerial Council. Funding of $US700,000 per annum

would be provided out of Joint Authority revenues for the following two years

to train East Timorese in administration and policy development in relation to

the Timor Gap Treaty and the resources covered by it. Also, a steering

committee would be formed to look at petroleum related training and employment

for East Timorese in the Timor Gap petroleum fields and associated areas.[59]

Attitude of the East Timorese

4.40

A CNRT

Statement on Timor Gap Oil dated 22 July 1998, signed by Dr

Ramos-Horta, Dr Mari Alkatiri and Mr João Carrascalão said:

The National Council of Timorese Resistance will endeavour to

show the Australian Government and the Timor Gap contractors that their

commercial interests will not be adversely affected by East Timorese

self-determination. The CNRT supports the rights of the existing Timor Gap

contractors and those of the Australian Government to jointly develop East

Timor’s offshore oil reserves in cooperation with the people of East Timor.

4.41

The Committee was

assured that there was a spirit of goodwill by all the parties for projects

under the Treaty regime to proceed successfully. According to Mr Stephen Payne, General

Manager, Petroleum Exploration and Development Branch, Department of Industry,

Science and Resources:

We certainly recognise the

importance of that stability and predictability for a project like Bayu-Undan,

which is a massive project. With the first phase of it, you are looking at

$US1.4 billion and you are looking at long-lived projects so companies,

understandably, need stability so they can make their decisions on investments.

We have had indications from the East Timorese leadership ... that they are

conscious of the need for the Treaty to continue to operate in a way that

companies understand and which is predictable. [60]

4.42

With respect to

future developments, Mr Payne told the Committee that Australia’s approach had

always been that there ought to be one set of rules for all projects under the

Treaty, as had been the case with Indonesia. He said that Phillips had received

an assurance from the East Timorese leadership, which had been taken into

account before the companies made their decision to commit to the first stage

of the Bayu-Undan project. The terms of that assurance talked about future

projects as well as existing ones.[61]

4.43

At the hearing on

18 November 1999, Mr Abel Guterres, Chairman of the East Timor Relief

Association, told the Committee:

Touching a little bit on the

Timor Gap Treaty, I am sure the leadership has expressed that the bulk of the

agreement will remain. But a time will come when people in the leadership will

express their views on the subject. At this stage not a lot has been discussed

because everyone is concentrating very much on the emergency needs of that

population, that is, shelter and food. Hopefully, by some time next year, once

UNTAET takes over, we can get that planning and those processes in train ... I do

not think we would touch on the core aspect of the agreement because it is a

waste of time ... I think there could be concerns in terms of taxation and

royalties that may go to East Timor in terms of increase.[62]

4.44

The Committee was

assured by the Attorney-General’s Department that there were no legal barriers

to East Timor and Australia signing off on a future agreement on the Zone of

Co-operation.[63]

4.45

The East Timorese

spokesman on Timor Gap matters, Dr Mari Alkatiri, stated on 10 November 1999 in

reference to the letter to Phillips Petroleum signed by Mr Gusmão, Dr

Ramos-Horta and himself giving an assurance that they would honour the Treaty

arrangements:

Yes, it was sent ... but that

doesn’t mean we have already accepted the Treaty as it is. It’s not a problem

of oil and gas, it’s a problem of maritime borders ... I think we have to

redefine, renegotiate the border later on when East Timor becomes independent.[64]

In a further

statement in Jakarta on 29 November 1999, Dr Alkatiri said:

We still consider the Timor

Gap Treaty an illegal treaty. This is a point of principle. We are not going to

be a successor to an illegal treaty.

Dr Alkatiri said the East Timorese were willing to

make transitional arrangements so that existing operators could continue their

projects. Negotiations between the United Nations, Portugal and Australia were

under way to sort out intermediate arrangements, he said.[65]

4.46

The Treaty was designed to expire after 40

years, in 2029. At that time, if not before, the contracting parties would have

the options of renewing it for a further twenty years, re-negotiating the

Treaty as an interim arrangement, or attempting to negotiate a seabed treaty.

It is important to note that the boundaries of Zone A, the shared area, were drawn

with reference to the seabed boundary between Indonesia and Australia agreed to

in 1972, which is closer to Indonesia than the mid-point between the two

countries. If the Treaty were re-negotiated so that Zone A was shifted to sit

closer to Australia astride the mid-line with East Timor, or if the Treaty were

replaced by a seabed treaty which took the mid-line as the boundary, East Timor

would come into possession of the bulk of the prospective hydrocarbons

deposits.[66]

Alternatively, there could be re-negotiation of the respective shares of

revenue from the Zone going to both parties: Dr Ramos-Horta declared on 7 May 2000 that

East Timor was entitled to up to 90 per cent of the revenues.[67]

It should be noted that the Treaty covered revenue sharing arrangements only

for petroleum; natural gas revenues were not explicitly included in the Treaty,

although the Committee was told at the hearing on 11 November 1999 that ‘the

approach had always been that there ought to be one set of rules for all

projects under the Treaty ... That helps companies when they are making the major

investment decisions that they do when you are talking about oil and gas

developments’.[68]

4.47

On 15 June 2000, Dr Alkatiri announced CNRT

policy on the Treaty. The CNRT would be seeking, prior to UNTAET relinquishing

its mandate, a new seabed boundary drawn an equal distance between East Timor

and Australia as the starting point for negotiations on a new oil and gas

revenue-sharing agreement. He said: ‘We are not thinking of renegotiation but a

new treaty. Of course, some of the terms will be the same but the starting

point needs to be the drawing of a maritime boundary between our countries and

that means the Treaty would not have any effect any more’.[69]

4.48

Dr Alkatiri was visiting Canberra as part of an UNTAET

team to negotiate with Australia on a new treaty. Another member of the team,

UNTAET’s Director of Political Affairs Peter Galbraith, made a statement

following the talks, saying:

What UNTAET seeks is what the East Timorese seek. The East

Timorese leadership has made it clear that the critical issue for them is to

maximise the revenues of the Timor Gap. The legal situation is this: UNTAET has

to continue the terms, but only the terms of the old Timor Gap Treaty and only

until independence. Therefore a new regime will have to be in place on the date

of independence.[70]

4.49

The Australian Government’s position was stated

by a spokesman for Foreign Minister Alexander Downer on 11 July 2000, who said

that Australia ‘understands the discussion or debate is about the share of

revenue; it’s not delimitation of the seabed’.[71]

4.50

Speaking at a CNRT congress in Dili on

26 August 2000, Dr Alkatiri said East Timor wanted its maritime boundary

with Australia to be equidistant between the two countries, which would put all

the current oil and gas activity in the Timor Gap on East Timor’s side. He

stressed the need for a new legal instrument so as not to retroactively

legitimise the 1989 Treaty: ‘We refuse to accept that East Timor be the

successor to Indonesia to the Treaty’.[72]

Mr Galbraith said in a radio interview on 10 October 2000:

UNTAET's position, acting on behalf of the East Timorese people,

is that the royalties and the tax revenue from the area north of the mid-point

should come to East Timor, and if there is not going to be a maritime

delimitation East Timor, however should have the same benefit as if there were

a maritime delimitation. That, after all is what East Timor is entitled to

under international law.[73]

4.51

In the same interview, Mr Galbraith said that

any state, including the independent country of East Timor, had the option of

going to the International Court of Justice to seek a maritime delimitation.

‘Hopefully’, he said, ‘it won’t come to that because an agreement acceptable to

the East Timorese will be negotiated and in place by independence’.

4.52

On 18 September 2000, Foreign Minister

Alexander Downer, Resources Minister Nick Minchin and Attorney General Daryl

Williams announced that Australian officials would travel to Dili for a

preliminary round of negotiations over three days from 9 October with UNTAET

and East Timorese representatives on rights for future exploration and

exploitation for petroleum in the Timor Gap. The Ministers said the aim of the

talks was to reach agreement on a replacement for the Timor Gap Treaty to enter

into force on East Timor’s independence. ‘It is expected there will be several

rounds of talks’, they said. ‘Australia currently has an agreement with UNTAET

which provides for the continued operation of the terms of the Timor Gap Treaty

originally negotiated with Indonesia. It will expire on the date East Timor

becomes independent.’ The Ministers said it was necessary to avoid a legal

vacuum and to provide commercial certainty for the petroleum industry operating

in the gap: ‘The eventual export of petroleum by pipeline from the Timor Gap to

Darwin would bring considerable benefits in terms of Australian regional

development. It is very important that there is a seamless transition or

arrangements governing petroleum exploitation in the Timor Gap. These

negotiations are a first step in that direction.’[74]

4.53

As already mentioned, there are two ways of

providing East Timor with a better deal than the present 50:50 split as set out

in the Timor Gap Treaty:

- by opting for a mid-point delimitation in a seabed boundary

treaty rather than the joint co-operation zone on which the Timor Gap Treaty

was based; or

- by providing East Timor with a generous share of the royalties

derived from Area A in the joint zone of co-operation in a renewal of the present

treaty - in effect, abolishing the distinction between ZOC A and ZOC C.

4.54

The Law of the Sea Convention, which entered

into force in 1994, is not prescriptive about the basis for delimitation.

Article 83 (1) reads:

The delimitation of the continental shelf between States with

opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of

international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the

International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution.[75]

4.55

Article 38 of the Statute of the International

Court of Justice reads:

The Court, whose function is to decide in accordance with

international law such disputes as are submitted to it, shall apply:

- international conventions, whether general or particular,

establishing rules expressly recognized by the contesting states;

- international custom, as evidence of a general practice

accepted as law;

- the general principles of law recognized by civilized

nations;

- subject to the provisions of Article 59, judicial decisions

and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various

nations, as subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law.

- This provision shall not prejudice the power of the Court to

decide a case ex aequo et bono, if the parties agree thereto.

4.56

Although the Law of the Sea Convention does not

prescribe the median point for delimitation purposes, the median point is now

generally accepted as the basis for delimitation. It should be noted that

Australia adopted the median line in 1981 as the fisheries boundary.

4.57

If the midpoint were adopted as the basis for

delimitation purposes in a seabed boundary between Australia and East Timor,

the current ZOC A would be located in East Timorese territory. It could also

have implications for the boundary between Australia and Indonesia as the new

Australia-East Timor boundary would be south of the two tripoints marking the

Timor Gap in the Australia-Indonesia boundary. This could lead to Indonesian

claims for a revision of its boundary with Australia. There could also be other

ramifications.

4.58

In view of current international law, if the

boundary between Australia and East Timor were confirmed as being a more or

less straight line between the two tripoints marking the Timor Gap in the

Australia-Indonesia boundary, Australia would be under at least a moral

obligation to direct most of the revenue flowing from oil and gas production in

Area A to East Timor. The ratio of 90:10, as claimed by East Timor, would not

be unreasonable.

4.59

The Committee believes that it is in Australia’s

interest for East Timor to become a viable nation; one that does not remain a

mendicant state and one that can play a constructive role in regional affairs.

In one way or another, Australia has had an association with East Timor for

almost 60 years and, for about half of that time, not one which has been

particularly creditable to Australia. Although Australia did much to regain its

reputation through its role in the establishment and deployment of Interfet, it

has an opportunity in current negotiations on the Timor Gap Treaty to cement

its future relations with East Timor.

4.60

Australian policy towards East Timor has often

been characterised as one in which pragmatism, expediency and short-term

self-interest have prevailed at the expense of a more principled approach. As

is now evident, such foreign policy characteristics have not always been in

Australia’s long-term interests. By acting honourably and taking account of

current international law, the Australian Government might not only earn the

good will of East Timor but also of other interested parties, as well as

providing East Timor with an economic basis on which it might be able to reduce

its dependency on foreign aid. Any such reduction would, of course, also

benefit Australia. However, the Committee does not believe that foreign aid

should be used as a lever in the current negotiations.

4.61

The commercial operators have expressed concern

relating to the outcome of the negotiations. In the event of unduly protracted

negotiations, commercial operators could defer further decisions on investment

in the Timor Sea. Any such decision would undoubtedly have adverse effects for

both East Timor and Australia. In addition, as indicated by Mr Peter Galbraith,

East Timor could also take the matter to the International Court of Justice

should it regard Australia as being unduly intransigent. Such a course of

action, which could result in lengthy proceedings, would be inimical to

Australia’s interests and international standing.

4.62

In the Committee’s view, it is incumbent on

Australia at this time to act generously towards East Timor to provide it with

the means by which it can develop a society and economy in keeping with the

region. The revenues from oil and gas royalties would inevitably become the

cornerstone of its future economic and social development.

Recommendation

The Committee RECOMMENDS that, in its

negotiations with UNTAET on the future of the Timor Gap Treaty, the Australian

Government should take into account current international law in relation to

seabed boundaries, the history of our relations with the East Timorese people,

the need to develop good bilateral relations with East Timor and the need for

East Timor to have sources of income that might reduce dependency on foreign aid.

Cartography by Chandra

Jayasuriya originally prepared for: Victor Prescott, ‘East Timor’s Potential

Maritime Boundaries’, presented at East Timor and its Maritime Dimensions:

Legal and Policy Implications for Australia, Australian Institute of

International Affairs, Canberra, 14 June 2000.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page