Chapter 7 - Quality improvement programs

7.1

This chapter discusses the

inquiry’s terms of reference relating to the effectiveness of quality

improvement programs to reduce the frequency of adverse events. While the terms

of reference specifically focus on programs for quality improvement much of the

evidence received by the Committee discussed quality improvement in general

terms. This chapter focuses on these broader issues as the evidence indicated

that a discussion of quality improvement cannot be solely restricted to its

impact in addressing adverse events given the impact of these programs on other

quality of care issues.

7.2

It was highlighted during the

inquiry that the community has a right to expect that the quality of care in

public hospitals meets the highest standards. While most treatments carry some

risk, the hospital system should be organised to minimise those risks and the

extent of any injury which might result from an adverse event. A concern for

safe, high quality care should permeate the whole public hospital system.[367] While evidence to the Committee

indicated that the quality of public hospital services in Australia

is of a generally high standard it was emphasised during the inquiry that in

several critical areas safety and quality could be enhanced.[368]

7.3

Several Australian studies in

the 1990s have focussed on the issue of quality and safety in health care. The

1995 Quality in Australian Health Care Study focussed particular attention on

safety issues by suggesting that a higher than expected number of hospital

admissions were associated with adverse events. Following the release of the

findings of the study, the Taskforce on Quality in Australian Health Care was

established in June 1995 to consider the data and report to Australian Health

Ministers on measures to reduce the incidence and impact of adverse events in

the health care system. The Taskforce reported to Health Ministers in June

1996. In March 1997, the National Expert Advisory Group on Safety and Quality

in Australian Health Care was established to provide practical advice to Health

Ministers on further steps to improve safety and quality of health care

services. The National Expert Group presented its Interim Report to Health

Ministers in July 1998 and its Final Report in August 1999.[369]

Definition of quality improvement

7.4

The subject of quality in

health care has been described as ‘bedevilled with definitional confusion and

ambiguities’.[370] Terms such as

‘quality’, ‘quality improvement’ or ‘quality assurance’ are often difficult to

precisely define and are often used interchangeably. During the inquiry, a number of terms were

referred to when describing quality of care issues including ‘quality

improvement’, ‘quality management’ and ‘quality assurance’. ‘Quality

improvement’ in the context of hospitals has been defined as the end result of

effective quality management and can be measured in relation to the degree to

which practices in hospitals result in the production of known or assumed

maximum health status improvement for patients. Quality improvement has three

components - identifying problems within hospitals, for the most part

identifying system defects; resolving those problems; and measuring the

resultant improvement.[371]

7.5

‘Quality management’ has been

described as an umbrella term that includes a wide range of hospital activity

designed to produce a ‘quality mature’ hospital. Quality management includes

such activity as quality assurance, risk management, credentialling of medical

staff, incident reporting and analysis, adverse events monitoring, quality

assessment and quality improvement. A ‘quality management program’ is defined

as an organised, coherent, range of activities that will enable the hospital

and its medical staff to improve the quality of care provided.[372] ‘Quality assurance’ has been

described as the process of ensuring that clinical care conforms to criteria or

standards and is a subset of quality management.[373] Generally the term ‘quality

improvement’ is used throughout this chapter as it relates directly to the

terms of reference and is the term most commonly used in submissions and other

evidence to the inquiry.

Nature and extent of adverse events

7.6

There is little data on adverse

events in Australia. The 1994 the Quality in Australian Health Care Study

(QAHCS) was commissioned by the then Commonwealth Department of Human Services

and Health to determine the proportion of admissions associated with an adverse

event (AE) in Australian hospitals.[374]

This was the first published study in Australia that attempted to identify

quality of care problems in Australian hospitals.

7.7

There is no nationally or

internationally agreed definition of what constitutes an adverse event. In the

Australian context, the Quality in Australian Health Care Study defined an

adverse event as ‘an unintended injury or complication which results in

disability, death or prolongation of hospital stay, and is caused by health

care management rather than the patient’s disease’.[375]

7.8

The QAHCS study found that 16.6

per cent of hospital admissions were associated with an adverse event and 51

per cent of the adverse events were considered preventable.[376] While in 77.1 per cent of cases the

disability had resolved within 12 months, in 13.7 per cent the disability

was permanent and in 4.9 per cent the patient died. For the two categories of

‘death’ and ‘greater than 50 per cent permanent disability’, the proportion of

high preventability were 70 per cent and 58 per cent respectively. There was a

statistically significant relationship between disability and preventability,

with high preventability being associated with greater disability.[377] The proportion of admissions

associated with permanent disability or death due to adverse events increased

with age; however temporary disability and preventability were not associated

with age or other patient variables.

7.9

A significantly lower

proportion of the adverse events were reported for obstetrics (7.2 per cent)

and ear, nose and throat surgery (7.9 per cent) than for other specialities,

while a higher proportion were associated with digestive (23.2 per cent),

musculoskeletal (21.9 per cent) and circulatory (20.2 per cent) disorders.

7.10

The study found that

extrapolating the data on the proportion of admissions and the additional

bed-days associated with adverse events to all hospitals in Australia in 1992

indicated that about 470 000 admissions and 3.3 million bed days were

attributable to AEs.[378] The study

also found that the number of patients dying or incurring permanent disability

each year in Australian hospitals as a result of AEs was estimated to be -

18 000 deaths, 17 000 cases with permanent disability, 50 000

cases resulting in temporary disability and 280 000 cases of temporary

disability.[379]

7.11

A Victorian study recorded an

adverse event rate of 5 per cent of separations using inpatient data from all

public and private acute care hospitals in that State in 1994-95. Most (81 per

cent) were complications after surgery or other procedures; 19 per cent

were adverse drug effects; and 1.7 per cent were misadventures.[380] The study has, however, been criticised

on the basis of the less rigorous definitions it employed than the Quality in

Australian Health Care Study.[381]

7.12

The cost to the Australian

health care system of adverse events in hospitals has been estimated at $867

million per year. Over a five year period this would amount to $4.3 billion.

This estimate does not include any subsequent hospital admissions and

out-of-hospital health care expenses, loss of productivity of the patients

involved, and the long term community costs of permanent disability from AEs.[382] The National Expert Advisory Group

estimated that the extrapolated potential savings from preventable AEs in

1995-96 would be $4.17 billion.[383]

7.13

Regarding overseas comparisons

of AEs, the Australian study found that when expressed as a rate of adverse events

per admission, the rate of hospital admissions associated with an adverse

events was 13 per cent compared to the rate of 3.7 per cent in the Harvard

Medical Practice Study in the United States on which the Australian study was

modelled. The study noted that the considerably higher rate recorded in the

Australian study may have been due to the fact that the US study was concerned

with medical negligence and malpractice, whereas the Australian study focussed

on prevention - which may produce different incentives for the reporting of

AEs. In addition, while both studies surveyed medical records - the US study in

1984 and the Australian study in 1992 - the quality of the medical records may

have improved in the intervening years. These factors suggest that the US study

could have underestimated the AE rate.[384]

7.14

The Committee considers that

the extent of adverse events highlighted in these various studies are

disturbing. The implications in terms of preventable adverse outcomes and the

use of health care resources are substantial, especially as the Quality in

Australian Health Care study suggests that in up to half of all adverse events

practical strategies may be available to prevent them.

Current approaches to quality improvement

7.15

The main quality improvement standard

in the Australian health care sector is the Australian Council on Healthcare

Standards (ACHS) accreditation and quality improvement program. The Council

supports health care organisations in their implementation of quality

improvement; develops and reviews quality standards and guidelines in

consultation with the industry, professional bodies and consumers; benchmarks

clinical care through the collection, analysis and dissemination of clinical

indicators; and advises on health care quality improvement.

7.16

ACHS’ quality improvement

program - the Evaluation and Quality Improvement Program (EQuIP) - is a

continuous quality improvement program that provides a framework for

establishing and maintaining quality care. EQuIP requires an integrated

organisational approach to quality improvement by assisting health care

organisations to improve overall performance; develop strong leadership; and

focus on a culture of continuous quality improvement with an emphasis on

patients and outcomes.[385]

7.17

ACHS conducts surveys of

hospitals and awards accreditation on the basis of the demonstrated ability of

a hospital to demonstrate significant and continuous improvement. Participation

in the accreditation process is voluntary and larger hospitals are more likely

to seek accreditation.[386] As the

table shows, in 1995-96, 40 per cent of public hospitals were accredited,

representing 69 per cent of accredited public hospital beds. In 1997-98, 47 per

cent of public hospitals were accredited, representing 75 per cent of beds in

public hospitals.[387]

Table 7.1:

Accreditation of public acute care hospitals (a)

and average available beds, 1995-96

|

Public

Hospitals |

NSW |

Vic |

Qld |

WA |

SA |

Tas |

ACT |

NT |

Total |

|

Accredited hospitals |

100 |

55 |

25 |

26 |

38 |

3 |

2 |

- |

249 |

|

Non-accredited hospitals |

73 |

60 |

119 |

61 |

37 |

12 |

-

|

5 |

367 |

|

Total hospitals |

173 |

115 |

144 |

87 |

75 |

15 |

2

|

5

|

616 |

|

Proportion hospitals accredited |

58% |

48% |

17% |

30% |

51% |

20% |

100% |

-

|

40% |

|

'Accredited' beds |

13,861 |

9,410 |

4,401 |

3,432 |

3,098 |

1,061 |

769 |

-

|

36,032 |

|

'Non-accredited' beds |

4,300 |

2,787 |

5,567 |

1,439 |

1,653 |

174 |

-

|

570 |

16,489 |

|

Total beds |

18,161 |

12,197 |

9,968 |

4,870 |

4,751 |

1,235 |

769

|

570

|

52,521 |

|

Proportion beds 'accredited' |

76% |

77% |

44% |

70% |

65% |

86% |

100%

|

-

|

69% |

- All

acute care hospitals are included in this table whether or not

accreditation was sought. Hospitals are included in this table for

performance indicator purposes and for some jurisdictions excludes

multipurpose facilities, mothers and babies facilities and dental

hospitals.

Source: AIHW, Australia's Health 1998, Canberra 1998,

p.210.

7.18

There are a number of other

accreditation systems involved in the health care sector including those

related to community health, mental health, aged residential care, and general

practice. In addition, a number of other professional accreditation systems

exist through specialists’ colleges, health professional organisations and the

post graduate medical council.[388]

7.19

At the Commonwealth level there

are a range of activities and initiatives to promote safety and quality of

health care, which attempt to promote a national focus and an integrated approach

to quality and safety. The Department of Health and Aged Care (DHAC) stated

that ‘although the Commonwealth does not have responsibility for the day to day

running of public hospitals, [there]... are examples of where the Commonwealth is

currently working with other stakeholders to support quality and safety

improvement’.[389]

7.20

These initiatives are detailed

below:

-

Australian Council for Safety and Quality in

Health Care - the Council was established in January 2000 to act as a national

partnership between governments, health care providers and consumers to improve

the safety and quality of care. The Council will initiate research and identify

strategies to improve the quality and safety of health services and strengthen

the link between existing quality improvement programs.[390]

-

National Institute of Clinical Studies - the

Institute, which is yet to be established, will work with the medical

profession to identify, develop and promote best clinical practice across a

range of clinical settings, and encourage behavioural change by the medical

profession.[391]

-

Consumer Focus Collaboration - this organisation

was established in April 1997 and is a national body consisting of

representatives from consumer organisations, professional associations, State

and Territory health departments and the Commonwealth. Its aim is to strengthen

the focus on consumers in health service planning, delivery, monitoring and

evaluation. The goals of the organisation is to facilitate the provision of

information to consumers; to facilitate active consumer involvement in health

service planning, monitoring and evaluation; improve health service

accountability and responsiveness to consumers; and promote education and

training that supports active consumer involvement in health service planning

and delivery.[392]

-

National Resource Centre for Consumer

Participation in Health - the Centre became fully operational in May 2000. Its

aim is to assist service providers, such as hospitals, to improve their

strategies for involving consumers in developing their services and practices.

It has two functions, namely as a clearinghouse for information about methods

and models of community and consumer feedback and participation; and in the

longer term as a centre of excellence in consumer participation where clients can

seek assistance to develop, implement and evaluate feedback and participation

methods and models.[393]

-

Clinical Support Systems Project - the Royal

Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) is undertaking a consultancy for DHAC

to focus on the measurement and improvement of clinical care through the

implementation of clinical support systems. The College is working with

innovative and leading clinicians and hospitals to explore whether combining

the use of evidence with a systematic approach to clinical practice results in

more effective and efficient health care with a view to improving patient

outcomes.[394]

-

National Demonstration Hospitals Program - NDHP

is a Commonwealth funded program designed to identify and disseminate

information about best practice models for innovation in acute hospital care.

The effectiveness and transferability of these innovations are evaluated

through demonstration projects conducted in a range of hospitals. Phases 1 and

2 focussed on innovation in internal processes in hospitals to improve patient

care and resource management. Projects in Phase 3 are reaching beyond the

immediate acute care sector and are focussing on identifying and developing

systems and processes that link and coordinate all services delivered by the

acute and related areas of the health sector. [395]

7.21

Further information on these

projects is provided in discussion in this chapter on measures to improve

quality and safety in hospitals.

7.22

In addition to these

initiatives, under the current Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCAs)

approximately $660 million is allocated to the States and Territories to fund

and support quality improvement and enhancement practices in hospitals. This

requires Ministers to agree, on a bilateral basis, to a strategic plan for

quality improvement during the term of the Agreement. Progress under each plan

will be reviewed during the 2000-01 financial year.[396]

7.23

For example, in Queensland a

quality improvement program is being implemented by funding provided under the

AHCAs. Under the program over the period from 1999-2004 major activities to be

undertaken include requiring all services funded or provided by Queensland

Health to have in place quality and continuous improvement systems; ensuring

that all services participate in an endorsed accreditation program;

implementing systems to assess risk, including the monitoring of adverse

incidents and monitoring and evaluating quality performance criteria. The

program also aims to provide relevant information to consumers, which allows

them to make informed decisions regarding their own health and to measure

patient satisfaction and patient experience of health services particularly

with respect to outcomes.[397]

7.24

The Committee notes that there

is no means of knowing if the quality enhancement funds provided by the

Commonwealth are being spent effectively by the States. Under Clause 23 of

Schedule E of the AHCAs, each State and Territory has agreed to provide the

Commonwealth the following reports within five months of the end of each grant

year:

-

a statement to acquit the amount of funds

provided in the relevant grant year as Health Care Grants under the terms of

the Agreements; and

-

a certification that the Health Care Grant

funding received in the relevant grant year was expended on the provision of public hospital services.

7.25

Under Clause 24 of Schedule E,

each State and Territory has agreed that the reports referred to in clause 23

of Schedule E will be in the form agreed with the Commonwealth from time to

time. This acquittal form includes separate identification of components of

Health Care Grants paid to each State and Territory, including for quality

improvements and enhancement.

7.26

However, DHAC cannot provide

details of how each State/Territory has spent its quality improvement and

enhancement funds in the 1998-99 financial year because they are not required

to allocate the quality funding against specific projects or to reconcile this

funding at the end of each financial year. It is therefore not possible to

determine whether the $660 million provided to the States is being used to

drive quality improvements. Unless better financial accountability mechanisms

are put in place the ad hoc and unsystematic approach to quality improvements

in the Australian health care system will continue.

7.27

A range of activities are also

undertaken at the State and Territory levels towards supporting safety and

quality in health care. In NSW the Framework

for Managing the Quality of Health Services in NSW Health was developed in

1998 to provide a comprehensive approach to assessing the performance of Area

Health Services in NSW. The Framework which is currently being implemented on a

State wide basis identifies a number of dimensions of quality relevant to

patients and health providers, in the areas of ‘safety’, ‘effectiveness’,

‘appropriateness’, ‘consumer participation’, ‘efficiency’ and ‘access’.[398]

7.28

In South Australia, the

Department of Human Services has engaged the Australian Patient Safety

Foundation (APSF) to provide service infrastructure and monitoring software for

a comprehensive package to measure risk and the incidence of adverse events and

provide for analysis of these factors. The APSF system has been trialed and is

being introduced across the State.[399]

In Tasmania the State Government indicated that it is developing a comprehensive

quality plan to address adverse events and other quality issues.[400]

7.29

Evidence to the Committee

suggested that current quality improvement programs need to be improved to

reduce the frequency of adverse events. The Royal Australasian College of

Physicians (RACP), Health Issues Centre (HIC) & the Australian Consumers’

Association (ACA), reflecting much of the evidence stated that:

While there have been extensive efforts at Commonwealth, State

and hospital level in relation to quality improvement in hospitals, much of the

effort remains unsystematic and ad hoc.[401]

7.30

The Consumers’ Health Forum

(CHF) also noted that ‘effective quality improvement programs are essential to

reduce preventable injury and death in hospitals. These programs are currently

very ad hoc and “process”, rather than “outcome” oriented.[402]

7.31

Dr Lionel Wilson of Qual-Med

put the view starkly when he stated that:

...few if any such programs exist and those that do are largely

ineffective...Unfortunately, quality management programs barely exist in most hospitals

although sporadic efforts exist to implement a range of quality management

projects. It is this absence of program activity that accounts for the fact

that current activities are quite ineffective in reducing the frequency of

adverse events, or indeed, a wide range of additional quality of care issues.[403]

7.32

Dr Wilson stated that the

overall results of this situation are that ‘no patient in Australia can be

guaranteed high quality of care in any of our hospitals and there are no

worthwhile initiatives to reduce or even identify adverse events in most

hospitals resulting in high levels of avoidable mortality and morbidity’.[404]

Improving quality and safety in public hospitals

7.33

During the inquiry a number of

areas were highlighted where improvements to safety and quality of care in

public hospitals could be made. These issues are discussed below and include a

discussion of the role of the Australian Council for Safety and Quality in

Health Care; the need for improvements in data collection on adverse events, the

need for pilot projects to find solutions to system failures, the role of

financial incentives, improved accreditation processes, improved education and

training for health professionals; encouraging best clinical practice;

promoting greater consumer participation; and the development of performance

indicators.

Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care

7.34

At the August 1999 meeting of

Australian Health Ministers’ Conference all health ministers agreed to

establish the Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC)

to address the need for a national coordination mechanism to improve

Australia’s health care system and to support action at the local level.[405]

7.35

The National Expert Advisory

Group on Safety and Quality in Australian Health Care (the Expert Group)

recommended in 1999 that the Council be established to improve safety and

quality in health care through:

-

providing national leadership and coordination

of health care safety and quality activities;

-

developing an overall coherent plan for

improving the quality of health care services;

-

facilitating action by dissemination of

information about quality activities and their outcomes through appropriate

agencies and organisations;

-

promoting a systematic approach to safety and

quality within the health care system and within the community at large; and

-

providing advice to Ministers and the public

about the safety and quality of the Australian health care system.[406]

7.36

The Council’s subsequent terms

of reference reflect the recommendations of the Expert Group. The Council’s

stated role is to lead national efforts to promote systemic improvements in the

safety and quality of health care in Australia with a particular focus on

minimising the likelihood and effects of errors. The aims of the Council are

to:

-

provide advice to Health Ministers on a national

strategy and priority areas for safety and quality improvement;

-

develop, support, facilitate and evaluate

national actions in agreed priority areas;

-

negotiate with the Commonwealth, States and Territories,

the private and non- government sectors for funding to support action in agreed

priority areas;

-

widely disseminate information on the activities

of the Council including reporting to Health Ministers and the public at agreed

intervals.

In undertaking these tasks, the Council will:

-

work collaboratively with stakeholders, in

particular building on the existing efforts of health care professionals and

consumers to improve the safety and quality of health care;

-

establish partnerships with existing related

national bodies and organisations, in particular the National Institute of

Clinical Studies (NICS) and the National Health Information Management Advisory

Committee (NHIMAC) to facilitate action in agreed priority areas;

-

consider and act to improve health care in the

priority areas identified as a result of national consultations undertaken by

the National Expert Advisory Group on Safety and Quality in Health Care

including:

-

methods to enable increased consumer

participation in health care;

-

implementation of evidence-based practice;

-

agree a national framework for adverse event

monitoring, management and prevention including incident monitoring and

complaints;

-

effective reporting and measurement of

performance, including research and development of clinical and administrative

information systems;

-

strengthening the effectiveness of

organisational accreditation mechanisms;

-

facilitate smoother transitions for consumers

across health service boundaries; and

-

education and training to support safety and

quality improvement; and

-

co-opt members with specific expertise, and

establish sub-committees and reference groups as required.[407]

7.37

The Council comprises 23

members including experts in the areas of health care quality and safety;

education, training and research; and consumer members. Its membership reflects

the view of the Expert Group that the Council members be appointed from a range

of stakeholders including Commonwealth and State representatives, members of

learned Colleges and professional associations, hospitals and consumer

representatives.[408] The Commonwealth

and the States were asked to nominate members for the Council with the

Commonwealth negotiating with the States on the final list of nominees. All

Health Ministers agreed on the list of nominees for the Council. Mr Bruce

Barraclough, currently President of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons

and Vice Chair of the Committee of Presidents of Medical Colleges was appointed

Chair of the Council on 21 January 2000. The Council will receive $5 million in

core funding over five years from all governments.[409]

7.38

The Council has identified a

number of key priority areas that need to be addressed. These priority areas

are to:

-

develop a national reporting system for errors

that result in serious injury and death of patients;

-

address medication errors across the system,

including investigating IT support for health professionals;

-

provide support for consumer incident reporting

and feedback - what goes wrong and what

goes right;

-

establish mechanisms to review causes of

preventable deaths and the interventions that would improve practice;

-

establish programs to educate health

professionals across the spectrum - undergraduate and postgraduate - about safe

practice, quality improvement and communication;

-

investigate workforce issues such as skill mix,

supervision and workplace constraints across all professional groups;

-

examine methods of auditing practice to provide

feedback to clinicians about their performance against best practice standards;

-

examine a system to track implanted medical

devices;

-

look at the issue of credentialling and

licensing of health professionals with a view to development of national

standards; and

-

provide support for a national/international

conference on safety and quality in health care.[410]

7.39

It is envisaged that the

Council will initiate a detailed plan of action on these priority areas by June

2001.[411] The Council has identified

three priority areas in which it will focus its efforts in the first instance.

These are improvements in data collection and reporting mechanisms; more

effective ways to support the safe practices of health care professionals; and

re-design of systems to strengthen a culture of ‘safety improvement’ within

health care organisations.[412]

Role of the Council

7.40

Evidence to the Committee

indicated that there was general support for the establishment of the Council.[413] The Committee of Presidents of

Medical Colleges (CPMC) stated that with the establishment of the Council ‘we

have every hope that we will now get quality, particularly in dealing with

adverse events higher on the agenda, and that we will get some effective ways

of dealing with that’.[414] The

Australian Medical Association (AMA) noted that, in supporting the Council,

‘individual doctors and hospitals are putting in an enormous amount of effort

to improve quality, yet it needs a national focus that the Council can give’.[415]

7.41

The Centre for Health Program

Evaluation (CHPE) stated that an important role of a permanent quality

assurance group ‘would be the determination of core measurement and performance

indicators for each sector and specialisation, and the determination of the

validity of these instruments. This suggests the desirability of a capacity to

monitor work in other countries and to run pilot studies in Australia’.[416] The Expert Group envisaged that the

Council would support a number of pilot programs aimed at establishing national

standards and evaluation tools.[417]

The nature and extent of pilot programs undertaken by the Council have yet to

be considered by Health Ministers.

7.42

Professor Jeff Richardson,

Director of the Health Economics Unit, also stated that the Council should be

put under ‘very close scrutiny’ that they are implementing examples from around

the world in regard to best practice medicine.[418] Professor Guy Maddern representing

the South Australian Salaried Medical Officers Association (SASMOA) expressed

the view that while the Council may initiate action at the Commonwealth level

there is a concern that initiatives will ‘not get down to the state level where

in fact most or all of the public hospital dollars are spent’.[419]

7.43

Dr Wilson also added a note of

caution in relation to the Council questioning its composition the breadth of

its expertise. He noted that, while acknowledging the need for such a national

monitoring body on quality issues:

Unfortunately, what has been established is a reflection what I

call the Australian disease: it’s full of state representatives, and in some

case, their role would be to see that nothing changes the status quo in that

state. What is more, apart from some exceptions-notable exceptions-there is a

minimum of expertise on that council because they have been chosen for other

reasons, and this is a complex area and there is little expertise in this

country...What is required of a council like that is not something that

addresses the political difficulties between the federal government and the

states...but one which applies a good deal of expertise to the problem...I have

some hesitation as to whether that council will be terribly effective.[420]

7.44

With regard to composition of

the Council, of its 23 members, nine are representatives of Commonwealth and/or

State and Territory health departments. This indicates that of the total

Council membership some 40 per cent are Commonwealth or State representatives.

The Committee shares the concerns expressed by Dr Wilson that this may be an

overly large representation of government officials, a representation that

would need to be matched by a strong commitment of those representatives to

establish an effective partnership between the Commonwealth, the States and

other key stakeholders to advance safety and quality issues in Australia.

7.45

As to the perceived lack of

expertise on the Council the Committee notes the concerns expressed. The

Committee notes, however, that the Council has a number of noted professionals

and other experts in the area of quality and safety. The Committee does,

however, consider that the composition of the Council and the range of

expertise represented should be kept under review.

7.46

The Council’s lack of formal

links with the health system is also of concern to the Committee. Under the

current structure the Council lacks the ability to make sure its strategies are

implemented across the health care system. The Council can produce reports and

strategies and make recommendations to the Health Ministers but it has no

mechanism to directly drive cultural change and institutional reforms.

7.47

The Expert Group considered

that the Council and its performance should be reviewed prior to the conclusion

its first four year term.[421] The

Government determined that the term of the Council would be five years but did

not put a formal review process in place. The Committee believes that the

Council should be reviewed after two years of operation, and that this review

should consider, among other things any change in the structure and composition

of the Council and the degree to which its aims and objectives are being met.

7.48

Some evidence suggested that

there should be a statutory body established to oversee quality issues. The

Australian Healthcare Association (AHA) argued that the most effective way to

deal with these issues would be to have an independent statutory body at least

to oversee the implementation of the Expert Group’s report.[422] AHA also suggested that while there

are a number of organisations that are involved in various aspects relating to

quality ‘none of them...have the independence, freshness or breadth in their

current brief to be able to do that’.[423]

The Committee sees merit in this proposal and believes that a statutory

authority should be established to oversee the quality programs.

7.49

The Committee has some concerns

at the level of resources devoted to the Council. As noted above, Health

Ministers have agreed to funding of $1 million per year over five years ($5

million in total) for operating costs. The Task Force argued that funding of

$17.4 million ($4.35 million per year over four years from 1999-00) should be

provided, which would allow for a number of targeted research, development and

dissemination activities suggested by the Expert Group (as outlined above).[424] The Council advised that Health

Ministers would consider additional resources for the Council at their meeting

in July 2000.[425] At their meeting,

Health Ministers agreed, in principle, to provide $50 million over five years

for the Council to lead a ‘national program of work to improve the safety and

quality of care’.[426] The Health

Ministers agreed to provide $5 million for a one year work program and the

Council will provide a report to Ministers on progress. Both of these

commitments were in line with the recommendations of the Council in its first

report to Health Ministers.[427]

Further commitment of funds by Health Ministers to the Council will be

dependent on the progress and results of this one year program of work.

Conclusion

7.50

The Committee believes that new

quality funding arrangements that include financial incentives and penalties

linked to agreed national quality targets are required. To be effective the new

funding arrangement would need to be supported by an institutional body or

authority with the capacity to monitor and report on the achievements of

quality and safety outcomes of different health systems. Under the current

system there is no body that oversees quality and drives the required reforms.

7.51

Quality improvements are

currently limited to pilot projects and consequently there is no overall

requirement for the system to commit to quality improvements. Quality

improvements will remain an ‘optional extra’ in our health system until new

funding arrangements are developed and implemented that require specific

quality measures to be built into the entire system.

7.52

The Committee believes that the

Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care has the potential to

place quality improvement high on the national health agenda and to provide the

essential national leadership and coordination of safety and quality

activities. However, under the current funding arrangements State and Territory

health systems are not obliged to adopt the Council’s agenda. The Council’s

work needs to be supported by an independent statutory body that sets quality

improvement targets and reports on their implementation across the different

systems. An independent statutory body would overcome the ad hoc and unsystematic

approach that has characterised quality reforms in Australia. Funding for

quality programs needs to be made more accountable, especially the funds

provided through the AHCAs.

7.53

The Committee considers that

the Council should pursue a vigorous and pro-active program of reform aimed at

improving the quality of health care across the nation and that this program of

reform should be adequately resourced. In this regard, the Committee notes the

recent decision of Health Ministers to provide $5 million to the Council for a

one year program of work. The Committee notes, however, that this is only a

fraction of the funding needed, especially considering that the Taskforce on

Quality in Australian Health Care sought $166.3 million over five years when it

reported in 1996. It is also only a fraction of the total cost to the health

care system of adverse events which has been estimated at $867 million per

year. The Committee is concerned that the Council will require increased

funding to enable it to fulfil its functions. The Committee also notes the very

long time taken for the Government to address the quality agenda. The Taskforce

reported in 1996 but the Council was not established until January 2000.

Recommendation 25: That a national statutory authority be established

with responsibility for improving the quality of Australia’s health system.

This authority would be given the task of:

-

collecting and publishing data on the

performance of health providers in meeting agreed targets for quality

improvements across the entire health system;

-

initiating pilot projects in selected hospitals

to investigate the problem of system failures in hospitals. These projects

would have a high level of clinician involvement; and

-

investigating the feasibility of introducing a

range of financial incentives throughout the public hospital system to

encourage the implementation of quality improvement programs.

Recommendation 26: That the mechanism for distributing

Commonwealth funds for quality improvement and enhancement through the Australian

Health Care Agreements be reformed to ensure that these funds are allocated to

quality improvement and enhancement projects and not simply absorbed into

hospital budgets.

Recommendation 27: That the Commonwealth Government undertake a

review of the structure, operations and performance of the Australian Council

for Safety and Quality in Health Care after two years of operation.

Recommendation 28: That Commonwealth

and State and Territory Health Ministers ensure that the Australian Council for

Safety and Quality in Health Care receives sufficient funding to enable it to

fulfil its functions.

Collection of data on adverse events

7.54

Submissions emphasised the need

for common systems for the collection of information about adverse events and

incidents in Australia. The Australian Health Insurance Association (AHIA)

argued that all hospitals should be required to report incidents to a central

incident reporting system.[428]

7.55

Infections and medication

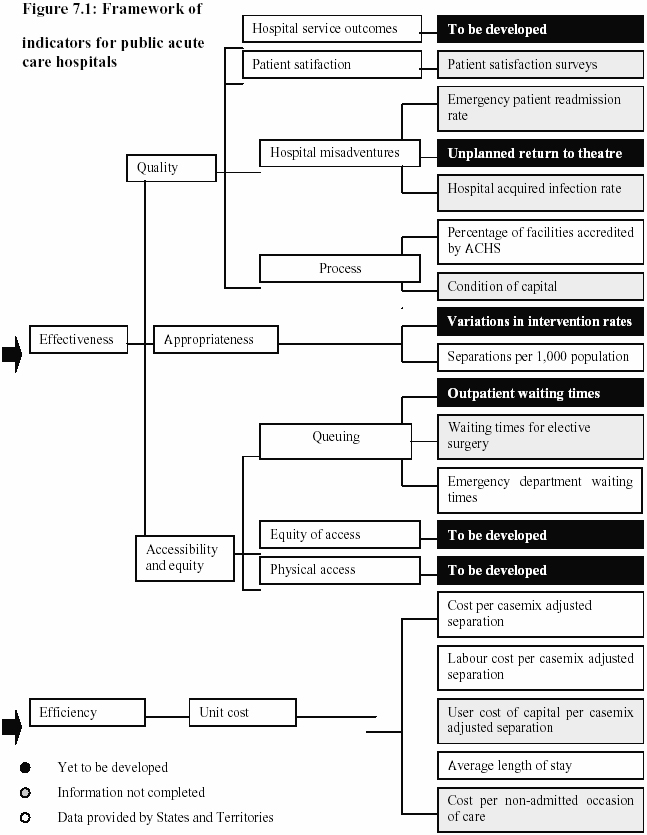

errors are the two areas that have been identified as the major contributors to

adverse events in several Australian and international reports.[429] Figure 7.1 in this chapter indicates

that data on ‘hospital acquired

infection rates’ are not yet completed and there is no mention in the chart of

data relating to medication errors.

7.56

In the United States in February this year the

US President, Bill Clinton, announced reforms to begin to reduce medication

errors:

I'm calling on the Food and Drug Administration to develop

standards to help prevent medical errors caused by drugs that sound similar or

packaging that looks similar. In addition, we'll develop new label standards

that highlight common drug interactions and dosage errors.

Hospitals that have already taken these steps have eliminated

two out of three medication errors. This is very significant. We tend to think

all our problems are the result of some complex, high tech glitch. We just want

to make sure people can read the prescriptions - two out of three of these

errors can be eliminated.[430]

7.57

The United States report To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health

System recommended:

a nationwide mandatory reporting system should be established

that provides for the collection of standardised information by state

governments about adverse events that result in death or serious harm. Reporting

should initially be required of hospitals and eventually be required of other

institutional and ambulatory care delivery settings.[431]

7.58

A comprehensive system of data

collection on adverse events enables the health system to identify and learn

from errors:

Reporting is vital to holding health care systems accountable

for delivering quality care, and educating the public about the safety of their

health care system. It is critical to uncovering weaknesses, targeting

widespread problems, analysing what works and what doesn't, and sharing it with

others.[432]

7.59

The Committee highlights the

urgency for the infection and medication error framework indicators to be

completed noting that they are necessary to inform the development of national

strategies to address these quality issues. The Committee believes that there

should be mandatory reporting of both medication errors and hospital acquired

infection rates and that these data should be made public.

7.60

There are a number of systems

and methods in place at present to collect information about incidents and

adverse events. These include the systematic audits of registers of death and

selected complications associated with particular procedures or treatments and

the Australian Incident Monitoring System (AIMS). AIMS is an incident reporting

system operated by the Australian Patient Safety Foundation. It is a voluntary

reporting system largely restricted to hospitals in South Australia and the

Northern Territory. Data on adverse events are also collected by the Australian

Council on Healthcare Standards as part of their surveys of facilities for

accreditation purposes.[433] Evidence

to the Committee indicated that these ad hoc attempts at data collection could

be improved by implementing a system aimed at collecting comprehensive and

consistent data across all hospitals nationally.[434]

7.61

The Expert Group argued that

systems need to be put in place to support the efficient collection of

incidents and adverse events - ‘these systems need to be simple, usable, robust

and must not add significant administrative burdens to those involved in their

use’.[435]

7.62

Several submissions called for

the establishment of a nationally consistent adverse incident reporting scheme.[436] The Expert Group also argued that

there was a need for State and Territory Governments, health care organisations

and other agencies involved in collecting data on incidents, adverse events and

complaints to agree on common systems for efficient collection and reporting

data on adverse events, with the capacity for national analysis of safety and

quality trends.[437]

7.63

The Committee notes that the

Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care has set as one of its

priorities the development of a national reporting system for errors that

result in serious injury and death of patients in the health care system.[438] The Committee strongly supports the

adoption of a uniform national approach to this problem as both necessary and

long overdue.

7.64

The Committee believes that the

national statutory authority could play an important role in overcoming the

current ad hoc approach and in establishing a national system of data

collection and reporting.

Recommendation 29: That a mandatory reporting system,

especially for hospital acquired infection rates and medication errors, be

developed as a matter of urgency.

Pilot projects

7.65

Submissions identified the need

for pilot studies with system wide application to find solutions to the system

failures which have been identified in the various studies of adverse events

both in Australia and overseas.[439] In

most studies of hospital systems, some form of system failure, for example, the

absence of, or failure to use policy, protocol or plan; inadequate reporting;

or inadequate training or supervision of staff is usually judged to be a

contributing factor in up to 90 per cent of cases of adverse events.[440]

7.66

Dr Wilson noted that most quality problems in

hospitals are not about individuals making mistakes but are due to system

failures. He added:

This is what happens when things do wrong in hospitals. The

person in charge of theatre was not there that day; someone else was there who

did not know the routine. The theatre team was new. The surgeon was not well or

had been up all night. A whole series of events go wrong. It is not just about

an individual misbehaving or behaving badly, or very rarely it is. It is mainly

a system failure.[441]

7.67

Dr Wilson further stated that:

Implementing effective quality management that ensures real

quality improvement, needs to be done slowly in a small number of facilities

with carefully managed and monitored pilot projects. Such projects will require

resources and will need to be evaluated to ensure that they are producing value

for money.[442]

7.68

CPMC noted that clinician

involvement in identifying and implementing solutions is crucial in any reduction

in the frequency of adverse events.[443]

The Committee notes that the Medical Colleges have indicated to the Department

of Health and Aged Care that they are ‘willing to take a leadership role in

these activities’.[444]

7.69

The Committee believes that the

problem of system failures in hospitals needs to be addressed and that pilot

projects to investigate this problem should be undertaken by the new statutory

authority. The Committee also believes that the connection between system

failure in hospitals and cultural change needs to be addressed. The Australian Council for Safety and Quality

in Health Care stated that there is a need for creating ‘changes in the culture

in which health professionals work from one of “judgement and blame” to one of

“learning for quality improvement”’.[445]

This cultural change will require more than just pilot projects, it will

require national leadership to implement findings on a national scale.

Recommendation 30: That the new statutory

authority to oversee quality programs initiate pilot projects in selected

hospitals to investigate the problem of system failures in hospitals and that

these projects have a high level of clinician involvement (see Recommendation

25).

Recommendation 31: That the issue of

cultural change within the hospital system be addressed, particularly the

capacity for improvements in information technology to drive change through

greater transparency and the adoption of consistent protocols.

Financial incentives

7.70

Evidence suggested that there

is a serious lack of financial incentives throughout the health system that

will promote quality of care. CHPE stated that:

The key issue is the lack of any reward under current payment

arrangements for the achievement of high quality care...The full potential of

financial levers is not explicitly recognised. In principle, a system committed

to quality improvement would embody incentives to achieve this objective at all

levels.[446]

7.71

Professor Richardson commented

that ‘when you change incentives and financial incentives you will actually

change behaviour. That behaviour change, usually with a time lag, is followed

by some sort of institutional change...there are any number of studies now from

any number of countries - primarily, the United States - which illustrate that

financial incentives do have a major effect’.[447]

7.72

Dr Wilson stated that:

There are no drivers at all for quality management in health

care. It is continually assumed that, if you have well-trained people, that is

enough. It is important, but it is not nearly enough, not in today’s world. So

that is the next thing: drivers. And they probably have to be financial drivers

because they are the most potent.[448]

7.73

A number of options were

suggested to address the issue of the lack of financial incentives. In the area

of private health insurance, AHIA suggested that the default payment should be

linked with quality criteria, that is, hospitals should not automatically be

entitled to benefits without meeting some degree of quality assurance, such as

the implementation of a recognised quality improvement program.[449] The Australian Private Hospitals

Association (APHA) argued that hospitals offering quality services should be

rewarded by insurers through financial incentives, in the form of higher

benefits.[450]

7.74

CHPE suggested that one option

would be to reduce default payments (preferably to zero) for non-participating

hospitals. The health insurance funds should be permitted to base their

selection of preferred providers on explicit performance indicators of quality

and be permitted to publicise what and why they have selected particular

providers.[451]

7.75

With regard to public

hospitals, Dr Wilson argued that financial drivers need to be applied to

hospital boards and management, who should have prime responsibility for

quality management and improvement programs. As noted above, he argued that at

present there are no incentives for a hospital managers to undertake the steps

necessary for ‘quality management’. ‘Quality management’, as discussed

previously, is a general term used to describe a range of hospital activity

which aims to produce a quality mature hospital. It includes activities such as

risk management, quality assurance and credentialling of medical staff. Dr

Wilson stated that the introduction of financial incentives available to

hospital managers who implement a stated range of quality management activities

that are verifiable within a certain timeframe, combined with a financial

sanction for failing to achieve designated goals, would substantially improve

quality and safety in hospitals.[452]

7.76

CHPE also suggested that the

use of ‘normative DRGs’ and other penalties/rewards should be explored. With

these, the cost weight per DRG would have a deterrent or reward loading which

could reflect under or over used procedures; origin of the patient in an over

or under serviced geographic location; the receipt of services from an

accredited hospital; and some other quality related activity such as discharge

planning and follow-up service.[453]

7.77

In relation to doctors, CHPE

argued that accreditation may be linked to a differential fee. This could be

extended so that a loading was added to fees when doctors indicated their

compliance with broad evidence based guidelines. The extent of their commitment

could, potentially, be monitored using routine administrative data.[454]

7.78

The Committee believes that the

new statutory body should explore the use of financial levers to encourage

improved quality of care in the hospital setting.

Recommendation 32: That the new statutory authority overseeing

quality programs investigate the feasibility of introducing a range of

financial incentives throughout the public hospital system to encourage the

implementation of quality improvement programs (see Recommendation 25).

Accreditation processes

7.79

A number of submissions argued

that there should be improved linkages and coordination between the range of

current accreditation and quality improvement approaches, in order to minimise

duplication and confusion for health service organisations regarding expected

standards of care. In the joint submission of the Australian Healthcare

Association (AHA), Women’s Hospitals Australia

(WHA) and the Australian Association of Paediatric Teaching Centres

(AAPTC) it was noted that in addition to the Australian Council on Healthcare

Standards there are now a number of other accreditation systems involved in the

health care sector including those related to community health and aged

residential care. A number of other professional accreditation systems also

exist through specialists’ colleges and health professional organisations.[455]

7.80

The Queensland Nurses’ Union

(QNU) raised the issue of how these separate processes interrelate and whether

there is a need for an ‘overarching framework’ that will facilitate the

involvement of all key stakeholders in activities relating to continuous

improvement in health - ‘we believe that better integration is required to

facilitate consistency of approach with respect to these matters’.[456] The Australian College of Health

Service Executives (ACHSE) expressed a similar view.[457]

7.81

ACHSE argued for the

establishment of an accreditation authority for all health services. The

authority would need to be independent of the funding authority and ensure that

there was effective stakeholder and consumer involvement.[458] AHA, however, arguing against the

creation of a national accreditation body stated that:

I think accreditation is part of the overall process of managing

risk and improving quality. I do not think it is the total answer to quality

and safety so I do not necessarily think a national accrediting body could take

responsibility for quality. However, I think an authority that has

responsibility for safety and quality could certainly have a look at the

plethora of accrediting bodies that are in place at the present time.[459]

7.82

AHA, WHA & AAPTC argued

that the Commonwealth and State Governments should collaborate in the

establishment of a national accreditation process for all types of health care

facilities.[460]

7.83

Submissions also noted that

accreditation currently focuses on quality control ‘processes’, that is, it has

a strong input focus. The Australian Nursing Federation (ANF) argued that to

strengthen its capacity to bring about significant reductions in the frequency

of adverse events, accreditation criteria ‘must be comprehensively linked to

the achievement of desired health outcomes’.[461]

AHA also stated that accreditation systems should move beyond the inputs,

processes and simple indicators of the quality of products to an approach that

is multidisciplinary in its focus to better reflect the nature of contemporary,

best practice care delivery systems.[462]

7.84

Some submissions also argued

that there was a need for more consistent national standards to underpin

quality improvement and accreditation approaches. Professor Don Hindle of the

School of Health Services Management at the University of NSW advocated the

‘adoption of national standards for quality of care and outcome measurement’.[463] AHA, WHA & AAPTC stated that the

proliferation of different standards for the same type of facilities, and of

different ways of measuring the same features in multiple settings is a major

concern of the Associations.[464] The

Expert Group noted that a first step should be to facilitate discussion and

debate about the underlying quality standards that should be key elements of

all quality improvement approaches.[465]

Recommendation 33: That the Australian Council for Safety and

Quality in Health Care review the current accreditation systems currently in

place with a view to recommending measures to reduce duplication in the

accreditation processes.

Education and training in quality improvement

7.85

Submissions argued that the

education and training available for health professionals and administrators at

all levels in quality improvement needed to be improved. ACHSE argued that:

greater emphasis and investment in education and training in the

philosophy and techniques of quality and safety are required for managers and

all health professionals. This will enable improved approaches to be

established effectively and new accountabilities to be met.[466]

7.86

The Australian Association of

Surgeons (AAS) argued that while formal quality improvement programs may

decrease the frequency of adverse events educational activities are usually

more cost effective.[467] The Doctors

Reform Society (DRS) also argued that quality improvement programs should be an

integral part of the on-going education of all medical practitioners.[468]

7.87

The Expert Group considered

that there would be benefits from the development of core quality management

aspects to be incorporated in all educational training provided to all health

professionals, whether they are being trained for clinical or administrative

roles. The Group also argued that there needs to be a national effort to

improve the education and training of health providers in safety and quality

matters and agreement on the curricula for continuous quality improvement for

inclusion in all undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing education and

training.[469]

7.88

The Committee notes that the

Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care has identified as a

priority area the establishment of undergraduate and postgraduate programs to

educate health professionals about safe practice and quality improvement.[470] The Committee supports this

initiative noting the concerns expressed in evidence about the need for

improvements in the education and training of health professionals in the areas

of safety and quality.

Encouraging best clinical practice

7.89

Evidence to the inquiry called

for the uptake of evidence-based health care and the further development and

implementation of best practice guidelines.[471]

‘Evidence-based health care’ is an approach to health care based on a

systematic review of scientific data. ‘Best practice’ in the health sector

refers to the highest standards of performance in delivering safe, high quality

care, as determined on the basis of available evidence and by comparison among

health care providers.[472]

7.90

The National Health and Medical

Research Council (NHMRC) stated that there has been an increasing move towards

developing clinical best practice guidelines.[473]

‘Clinical practice guidelines’ are systematically developed statements to

assist providers and users of health services to make decisions about

appropriate health care for specific circumstances. The purpose of best

practice guidelines is to improve the quality of health care, to reduce the use

of unnecessary, ineffective services or harmful interventions and to ensure

that care is cost effective. The NHMRC has been primarily responsible for the

development and implementation of clinical practice guidelines to assist health

care providers implement research into practice. There is also an increasing

trend for other expert bodies and the learned Colleges and professional

associations to develop clinical practice guidelines for endorsement by the

NHMRC. Most States have also invested in clinical effectiveness units to

promote evidence-based healthcare and to link research with local practice.[474]

7.91

NHMRC noted that with the

development of evidence-based medicine, guidelines are becoming one of the

critical links between the best available evidence and good clinical practice.[475] The guidelines are intended to be a

distillation of current evidence and opinion on best practice. Clinical

practice guidelines are sometimes referred to as clinical pathways, protocols

and practice policies, although these differ from clinical practice guidelines

in that they are often much more prescriptive and not always based on evidence.[476]

7.92

Quality assurance and quality

improvement activities have a complementary and reciprocal relationship with

clinical practice guidelines. Quality assurance activities encourage the

implementation of guidelines, and guidelines are a crucial component of quality

assurance activities. Continuous clinical practice improvement aims to improve

the quality of care by bringing together research on variation of cost, access,

quality and standardised care. It requires a knowledge of processes and

systems, human behaviour and an approach to continuous learning.[477]

7.93

During the inquiry witnesses discussed

aspects of these approaches. For instance, RACP supported the development and

implementation of clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based medicine.

RACP stated that it is currently undertaking the Commonwealth-funded Clinical

Support Systems Project (CSSP), an initiative which focuses on the measurement

and improvement of clinical care through the implementation of clinical support

systems. Such systems include clinical practice guidelines, clinical pathways,

consumer pathways and information technology for clinical decision support and

measurement of health outcomes. It is an approach that links clinical practice

improvement directly to medical evidence and aims to improve the efficiency and

quality of health care provision.[478]

7.94

Professor Hindle advocated the

clinical pathways approach. A clinical pathway is a document which describes

the usual way of providing multidisciplinary clinical care for a particular

type of patient, and allows for annotation of deviations from the norm for the

purpose of continuous evaluation and improvement. He agued that good clinical

teams in Australia and overseas are increasingly using clinical pathways.[479] He argued that:

Good clinicians want to work in teams. They want to specify how

they will work together...so it is sensible to write down the protocol for what

they will normally do. They are making these changes around Australia as we

speak because they recognise that it will help them allocate their scarce

resources-they won’t waste resources on that patient when they are better spent

on another of their patients. They will improve quality of care and outcomes by

avoiding duplication of care or missing out on care and so on.[480]

7.95

Professor Hindle argued that evidence from

around the world shows that clinical pathways improve quality of care and

reduce costs because the team works better, thus avoiding omission, duplication

and other errors. He suggested that the main barriers to the use of clinical

pathways are that some clinicians are reluctant to work in a team, or are concerned

to avoid anyone else being aware of, and consequently in a position to

criticise, their clinical practice.[481]

7.96

The Expert Group argued that

existing efforts to promote evidence-based practice through such groups as the

learned Colleges and NHMRC should continue to be supported by all

jurisdictions, Colleges and other relevant groups, and that this work should

form part of an overall national action plan for safety and quality

enhancement. The Expert Group considered that the focus on evidence-based care

should also be underpinned by a commitment to continuous quality improvement in

clinical practice. The Group also argued that national action should continue

to be taken to research, develop and encourage implementation of evidence-based

practice, including use of clinical practice guidelines and quality improvement

tools that reduce unexplained variation and improve aspects of quality across

the continuum of care.[482]

7.97

Some evidence indicated that

the development of clinical practice guidelines by the Colleges has been

relatively slow. Professor Richardson indicated that while a number of the

Colleges are investigating evidence based medicine the pace of reform is

‘leisurely’ in relation to the importance of the issue.[483] The Menadue report into the NSW

health system also commented on the slow development of clinical practice

guidelines by most of the Colleges, with some notable exceptions.[484] The Committee is concerned at this

development and encourages the learned Colleges to further facilitate the

development of clinical practice guidelines.

7.98

NHMRC also stated that there

needs to be greater attention given to implementation and evaluation of

guidelines once they have been developed. NHMRC noted that many of those

involved in producing guidelines have become frustrated by the lack of

implementation. Further, health care professionals’ acceptance of clinical

practice guidelines has to some extent been marred by concern that the

guidelines represent ‘cookbook’ medicine.[485]

One study suggested that there were marked variations in the uptake of

evidence-based methods among different practitioners in different fields of

medicine - the fields that have a higher reliance on technology, such as

neonatology, appear to adopt evidence-based practice styles more readily.[486]

7.99

The Committee notes the

proposed establishment of the National Institute of Clinical Studies. As noted

previously, the role of the Institute is to promote best clinical practice

throughout the public and private health sectors and encourage behavioural

change by the medical profession. The Committee notes that the Institute was

due to begin operations in January 2000.[487]

The Committee is disappointed at the delay in the establishment of the

Institute given its potential importance in promoting best clinical practice.

7.100

The Committee notes that

several witnesses stressed the importance of the Institute in addressing the

issue of best practice medicine. Professor Donald Cameron representing the RACP

stated that the Institute will be ‘looking at outcomes -clinically significant

outcomes, not the sort of thing that has happened in the past like some

satisfaction surveys which usually ask if the doctor was polite and nice and so

on’.[488] Professor Peter Phelan

representing the CPMC stated that the Institute would assist in promoting best

clinical practice:

There are considerable variations in medical interventions

across the community...they occur because there is not good evidence on which

these interventions are based, so doctors use their own experience. We have not

been able to provide them with information to allow them to make more informed

judgements. I think the initiative to establish a national institute of

clinical studies may well start to provide that sort of information to doctors

which can make them more informed.[489]

7.101

The Committee supports the

further development and implementation of evidence-based medicine and of

clinical practice guidelines. The Committee believes that a firm commitment to

evidence-based medicine will promote best practice and improve the quality of

health care.

Recommendation 34: That initiatives by the National Health and

Medical Research Council, the Colleges and other relevant groups to encourage

the development and implementation of evidence-based practice, including the

use of clinical practice guidelines, be supported.

Consumer participation in quality improvement

7.102

Evidence to the Committee from

consumer organisations highlighted the need to improve consumer participation

in the development of quality improvement programs and the health system generally.

Mr McCallum representing the Consumers’

Health Forum of Australia (CHF) stated that there was a need to:

...strengthen individual consumers and communities to think more

about the care they need, to make better choices about the care they access and

to become partners with the health system. It worries me that we will craft

solutions that will not involve the consumers and communities who might have

solutions for us in this.[490]

7.103

The CHF outlined a number of

requirements that they see as essential to any quality improvement program to

reduce adverse events. CHF argued that consumers should:

-

have access to their own medical records -

‘medical records are still one of the most important sources of information for

consumers trying to make sense of an adverse event’;

-

have access to effective information to help

consumers understand their treatment options;

-

have access to effective complaints mechanisms;

-

be informed when a mistake has been made or an

accident occurred as a result of the failure of the system, or of a medical

practitioner; and

-

participate in all levels of the health system.[491]

7.104

RACP, HIC & ACA also argued

that to promote a high quality public hospital system there needs to be

investment in better systems to promote ‘consumer-oriented care’. This includes

attention to best practice, clinical practice supports and protocols, the

measurement and analysis of variations in practice and health outcomes

measures.[492]

7.105

The Expert Group argued that

national action should continue to be taken to research, develop and

disseminate methods to enable better consumer participation in health care

service delivery, planning, monitoring and evaluation at all levels, including

strategies to improve the quality and accessibility of consumer health

information.[493]

7.106

DHAC stated that the

Commonwealth is working with consumer organisations, health service providers

and State/Territory Governments to increase consumer participation in the

planning, delivery and evaluation of health care. As noted previously, the

Consumer Focus Collaboration aims to improve the accountability and

responsiveness of the health care system to consumers.[494] The Collaboration is overseeing some

14 projects funded through the Commonwealth. These projects include:

-

Consumer and Provider Partnerships in Health

project - the aim of the project is to document the most effective approaches

available for teaching and learning the skills needed for effective

communication between health care consumers and providers. The consultant

undertaking the project will analyse the issue of education and training in

health care to promote active consumer involvement in health system planning

delivery and monitoring and evaluation.

-

Project to support nurses to involve consumers

in their own health care - the ANF and the Royal College of Nursing Australia

have been funded for a project to develop strategies to support nurses in

involving consumers in health care planning and delivery. A similar project

involving the AMA and the CPMC is undertaking a project to work with medical practitioners

to support their efforts to involve consumers in their health care.

-

Structural and Cultural Marginalisation in

Health Care project - the aim of the project is to identify ways that health

services have involved or sought feedback from groups of consumers who have