Chapter 4 - Coordinated Care Trials

4.1

This chapter discusses the

evolution and development of the Coordinated Care Trials and the effectiveness

of the trials in achieving better health outcomes for clients and in improving

service delivery. The purpose of the Coordinated Care Trials is to test whether

multi-disciplinary care planning and service coordination leads to improved

health and well-being for people with chronic health conditions or complex care

needs. Funds pooling between Commonwealth and State/Territory programs was

trialed as a means of providing funding flexibility to support this coordinated

approach to service delivery.[138]

Development of Coordinated Care Trials

4.2

The Coordinated Care Trials

were developed in response to a Council of Australian Governments endorsed

reform agenda in April 1995 that sought to meet Australia’s

health care needs in more appropriate ways while managing health expenditures

more effectively.

4.3

The then Department of Human

Services and Health called for expressions of interest in September 1995 to

establish trials that would develop and test innovative service delivery and

funding arrangements. Nine trials were approved by the Commonwealth and clients

were recruited from July 1997. Due to the complexity of the design phase, slower

than expected rates of recruitment and developments within the health system

that affected the trials and necessitated changes to their design, the

scheduled end date for the trials was extended to 31 December 1999.[139]

The coordinated care model

4.4

The coordinated care model

consists of:

-

a trial sponsor (such as an Area Health Service

or Division of General Practice) which is contracted to Commonwealth and State

governments to manage the trial;

-

a funding ‘pool’ which combines funds drawn from

a range of Commonwealth and State health care programs such as the MBS, PBS,

Home and Community Care Program and hospital funding. These funds can be used

to buy any services for individual patients considered appropriate;

-

a care coordination process which can be undertaken by a person (a local GP, a

community nurse or designated coordinator), or a service (such as an Aged Care

Advisory Team); and

-

a defined client group (usually people with high

care needs with a particular diagnosis or condition, or those with a range of

chronic illnesses). [140]

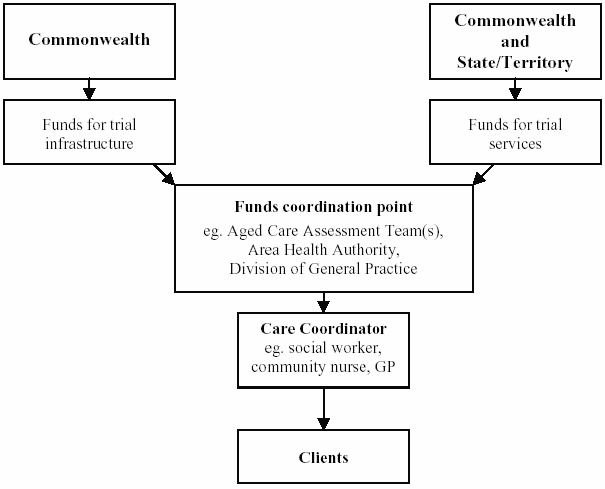

4.5

The organisational and funding

arrangements for the trials are shown below.

Figure 4.1: Organisational arrangements for trials

Source: Parliamentary Library, Coordinating Care in an Uncoordinated

Health System, May 1999, p.5.

4.6

The primary purpose of the

trials was to develop and test different service delivery and funding

arrangements, and to determine the extent to which the coordinated care model

contributes to improved client outcomes; better delivery of services which are

individually and collectively more responsive to clients’ assessed needs; and

more efficient ways of funding and delivering services.[141] As noted above, the Commonwealth and

the States pooled their funds for health and community services for each of the

trials’ participants. Infrastructure costs, relating to costs associated with

IT systems, office accommodation and evaluation costs were in some cases shared

between the Commonwealth and the States and in other cases were funded solely by

the Commonwealth. Although initially considered for inclusion, residential aged

care programs, such as nursing homes and hostels, were excluded as the funding

could not be easily transferred into the pool because these services are often

privately operated.[142]

4.7

Each trial had its own pool

that it had to manage in order to provide the best care possible for its

clients. The amount of money placed in each pool was based on an estimate of

what would otherwise have been spent on services used by clients who were participating

in the trials. Once an estimate for a trial client’s needs for a particular

service was calculated, that is, their needs were they not to enter the trial,

these funds were typically notionally allocated to the trial and funds

transferred monthly. Providers then billed the trial, or in the case of the MBS

and PBS, the Health Insurance Commission, and funds flowed between the trial

and the providers.[143] The following

table shows the fund pool income for each trial by item.

Table 4.1: Coordinated Care Trials:

fund pool income

|

|

Care 21

|

Care Net

|

Care Plus

|

Care

Works

|

Health

Plus

|

Linked Care

|

North Eastern

|

Southern HCN

|

TEAM

Care

|

|

MBS income

|

507 171

|

2 068 893

|

1 174 402

|

593 479

|

2 487 751

|

1 003 427

|

625 963

|

2 545 408

|

926 674

|

|

PBS income

|

487 197

|

1 825 086

|

763 966

|

502 342

|

1 544 598

|

878 971

|

505 600

|

1 164 850

|

731 454

|

|

DVA income

|

194 466

|

844 587

|

0

|

614 198

|

0

|

511 675

|

310 033

|

0

|

894 696

|

|

Hospital income

|

1 669 054

|

3 086 322

|

1 526 741

|

3 066 280

|

4 563 630

|

2 287 458

|

1 047 946

|

3 862 957

|

225 000

|

|

HACC income

|

437 500

|

247 122

|

531 088

|

585 353

|

481 685

|

985 883

|

496 888

|

0

|

0

|

|

RDNS income

|

267 905

|

0

|

0

|

152 459

|

638 512

|

683 753

|

219 435

|

53 973

|

0

|

|

Other income

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

71 738

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Total

|

3 563 293

|

8 072 010

|

3 996 197

|

5 514 111

|

9 716 176

|

6 422 904

|

3 205 865

|

7 627 188

|

2 777 824

|

Source: DHAC, The Australian Coordinated Care Trials: Interim Technical National

Evaluation Report, 1999, p.122.

4.8

Each client in a trial had a

care coordinator who worked with the client to develop a care plan. The care

coordinator then drew on money from the funding pool to buy the full range of

services set out in the care plan. The actual process of care coordination was

open to the trials to determine. The care coordination function incorporated

the assessment of clients, care planning process and care plan implementation,

monitoring and review. The three main models were:

-

Model 1: the GP approach - under which the

client’s GP undertook all tasks associated with the care coordination

role;

-

Model 2: the GP care coordinator with the

service coordinator approach - under which the GP functioned as the care

coordinator and was supported by a service coordinator who acted as an agent or

organiser for the GP with various delegated tasks such as implementation of the

care plan through the arrangement of services;

-

Model 3: the non-GP care coordinators approach -

under which the tasks were undertaken by specifically designated coordinators

who were not GPs.[144]

4.9

While some trials adopted one

of these approaches, others used a combination of approaches.[145]

4.10

There were nine general trials

operating in 5 States and the ACT. The Trials were: North Eastern Health Care

Network (Vic), Southern Health Care Network (Vic), HealthPlus (SA), Care 21

(SA), Care Net Illawarra (NSW), Linked Care (NSW), TEAMCare (Qld), Careworks

(TAS), Care Plus (ACT). The nine trials recruited a total of 16 533

clients with complex and chronic health needs. While the characteristics of the

target population varied slightly across the trials, clients were predominantly

older persons, aged over 65 years of age, who were socio-economically

disadvantaged. The trials had over 2000 GPs involved in their operation.[146] The main features of the general

trials are shown below.

Table 4.2: Coordinated Care Trials -

main features

|

Trial name

|

Location

|

Client Eligibility

Criteria

|

Target population

|

|

|

|

Age

|

Other Criteria

|

|

|

Care21

|

Northern suburbs of Adelaide, SA

|

65+

(55+

ATSI)

|

Complex health care needs, multiple

community/health service usage

|

1200

|

|

Care Net

|

Illawarra area of NSW

|

65+

(45+

ATSI)

|

At risk of falling and/or needing multiple

services

|

1800

|

|

Care Plus

|

ACT

|

All

|

Complex care needs, high users of health

services

|

2400

|

|

Careworks

|

Southern Tasmania

|

65+

|

Complex care needs requiring multiple

health services

|

1200

|

|

Linked Care

|

Hornsby & Ku-ring-gai areas of

Sydney, NSW

|

All

|

Chronic/complex care needs including

elderly and people with disabilities

|

1500

|

|

North Eastern HCN

|

North-eastern suburbs of Melbourne, VIC

|

65+

|

Diseases/disabilities typical of older

age (eg stroke, respiratory, cardiac)

|

1600

|

|

HealthPlus

|

Central, southern and western suburbs of

Adelaide and the Eyre Peninsula, SA

|

18+

|

Condition specific project criteria (eg

diabetes) or complex, chronic care needs

|

6000-8000

|

|

Southern Health Care Network

|

Outer suburbs of south-east Melbourne,

VIC

|

All

|

Greater than $4000 hospital episode(s) over

2 year period

|

2500-3000

|

|

TEAMCare Health

|

Northern suburbs of Brisbane, QLD

|

65+

(50+ ATSI)

|

Multiple service needs

|

3000

|

ATSI

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders

Source: DHAC, The Australian Coordinated Care Trials - Background Trial

Descriptions, 1999, pp.9-11.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander trials

4.11

In addition to the general

trials, there are trials for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The

Aboriginal Trials have a somewhat different focus, arising from the importance

of comprehensive primary health care and community involvement in addressing

health needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

4.12

The main purpose of Aboriginal

trials is to develop and assess innovative service delivery and funding

arrangements that are based upon community and individual care coordination

through pooling of funds from State and Commonwealth agencies. Aboriginal

Trials share many of the features of the general trials but there are some

important differences. Most are funded in respect of an entire community rather

than chronically ill individuals. MBS and PBS equivalent contributions to the

funding pool are at national average rates rather than an estimate of what

would otherwise have been spent on services, in recognition of historically very

low levels of MBS and PBS usage by Indigenous clients. Greater emphasis is

given to empowering communities as well as individuals to take control of their

own health needs. All Aboriginal trials

are implementing generic and individualised care plans with their client

populations as well as initiating new population health programs dealing with

issues such as diabetes and antenatal care.[147]

4.13

There are 4 Aboriginal

Coordinated Care Trials in 2 States and the Northern Territory: Wilcannia (Far

West Ward Aboriginal Medical Service) (NSW), Tiwi Islands (Tiwi Health Board

and Territory Health Services) (NT), Katherine West (Katherine Health Board,

Territory Health Services) (NT), Perth/Bunbury (a two site trial, Derbarl

Yerrigan Health Service, South West Aboriginal Medical Service, Health

Department of Western Australia) (WA).[148]

4.14

While the formal phase of the

Aboriginal trials is finalised, the trials will continue to receive funding by

the Commonwealth and States/Northern Territory during 2000 under transitional

arrangements after which the future of the trials will be determined.

Additional Coordinated Care Trials

4.15

The 1999-2000 Federal Budget

allocated $33.2 million to additional coordinated care trials over the next

four years to focus on people with chronic or complex care needs, with a

particular emphasis on older people who are chronically ill or disadvantaged.[149]

4.16

As with the current coordinated

care trials, the additional trials will be developed in collaboration with key

stakeholders, including State and Territory Governments, the medical profession

and other service providers, the non-government and charitable sectors, and the

private health sector. On 4 August 1999, all Australian Health Ministers

endorsed strategic directions for the additional coordinated care trials.

4.17

The primary purpose of the

additional trials is to build on the lessons of the current Coordinated Care

Trials, and further develop and test different service delivery and funding

arrangements. The trials are expected to run for three years. Trials

participating in the first round will have the opportunity to compete in the

second round of trials.

Evaluation of the trials

4.18

As noted previously, the aim of

coordinated care is to achieve better health and well-being for clients within

existing levels of resources (except for Aboriginal trials where increased

resources can also be a feature). The purpose of the trials is to test

different approaches to achieving this. Given this aim, a comprehensive

evaluation is a critical part of the program.[150]

Major interim evaluation reports on the general trials were published in

September 1999 and a final evaluation report is due in February 2001.[151] An

evaluation report on the Aboriginal trials is due in December 2000.

4.19

The Department of Health and

Aged Care (DHAC) stated that for the Aboriginal trials, all have implemented

public health and health service delivery initiatives targeting priority needs

of communities, with the aim of improving health outcomes. There are early

signs that improvements in Indigenous health indicators can be achieved when

services have sufficient resources to provide a sound base for primary health

care and where local communities take a strong role in developing and

delivering services. For example, at one

of the trials, the child immunisation rates have reached very high levels for

the first time. At another trial, preliminary data indicate a significant

increase in access by Aboriginal women to antenatal care services.[152]

4.20

Evidence to the Committee

during the inquiry, however, indicated some problems with the trials. The

Australian Medical Association (AMA) (NT Branch) argued that while in some

communities the trials are working well, including the Tiwi trial, there were

several problems ‘on the ground’ with these trials in relation to the availability

of doctors in Aboriginal communities and accountability in funding

arrangements. AMA (NT) stated that:

...the trials really will

not work unless there are more doctors on the ground in these areas...The second

thing is there is concern about the transparency of this paying out of funds

and where the money is actually going to and how it is being used by the

communities or the people who are the gatekeepers for these funds.[153]

4.21

AMA (NT) further stated that

the trials are ‘fine in terms of identifying unwell Aboriginal people, making

sure that they are followed up effectively and in getting the right

investigations done, but then it is actually treating these people and making

sure that you have done the groundwork, that you have worked out what is wrong with

them and you know what is needed to improve their quality of life. But actually

having the doctors on the ground to supervise that and to ensure that happens

is another problem’.[154]

4.22

The Northern Territory Branch

of the Australian Nursing Federation (ANF) also raised problems with

accountability. ANF (NT) noted that while the trials were ‘positive’ in that

they reflected a trend in Aboriginal communities of developing local control of

their own health services, the downside was a concern ‘about the sorts of

people that are attracted to the health boards that have been set up to run

those services’. It was argued that there was a need for more Commonwealth

scrutiny of the funds that are put into these programs.[155]

Effectiveness of the general trials

4.23

The interim evaluation report

of the general trials found that it was too early to conclude definitively that

the Coordinated Care Trials have achieved their objectives. The evaluation

report stated that the interim findings ‘cannot be seen as conclusive, but

rather should be used to give direction to future developments in coordinated

care’.[156] The report noted that the

complex nature of the trials and difficulties with ‘data flow, data quality and

data completeness, as well as by the diversity of trial populations and

processes’ made evaluation of the trials difficult.[157] The key findings of the interim

evaluation are outlined below.

Client health and well-being

4.24

The evaluation report stated

that the interim results of the trials on client health and well-being,

hospitalisation, re-admission and length of stay are inconclusive. Available

data indicate, however, that care coordination has not led to any significant

change in the health and well-being of the trial groups. The evaluation report

noted, however, that the data set is incomplete for some trials and that, while

the results are not statistically significant, trends suggest that some client

groups have experienced some improvements in their physical health status.[158]

4.25

A number of indicators of

health and well being were considered in the report, including hospitalisation

rates, re-admission rates within 28 days for the same cause, and length of stay

in hospital. The results showed that coordinated care had little or no effect

on these outcomes, with the exception of one trial that had lower hospital

re-admission rates.[159]

4.26

Regarding hospitalisation,

overall 25 per cent of clients had been hospitalised at least once over the

course of the trials, and this proportion was similar in the intervention and

control groups. The number of admissions that each person had was also similar

for the two groups. The proportion of re-admissions by trial varied

considerably, ranging from 6 to 16 per cent. Patients in the intervention group

of three trials had a statistically significant higher rate of hospital

re-admission than the control group. Only one trial had a statistically lower

rate of re-admission in the intervention group. After adjustments for age and

diagnosis-related group, these differences were no longer statistically significant,

with the exception of one trial that maintained a significantly lower rate of

re-admission in the intervention group. Regarding length of stay, while

individual trials did show some differences between intervention and control

groups, they were not statistically significant.[160]

4.27

Qualitative data were also

examined for evidence of the impact of care coordination on client health and

well-being. There were indications that some clients experienced an increased

sense of security as a result of having access to someone who could help them

to negotiate through the complexities of the health system. The perceptions of

moderate and high-risk clients were more positive than those of low-risk

clients, who tended to see care coordination as a hindrance rather than a help.

However, qualitative data were incomplete for some trials.[161]

Provider experiences

4.28

Providers include those

involved in the direct process of care coordination or in the delivery of

services.

4.29

In relation to GPs, not all

were willing to become involved in the trials. Their main concerns were the

additional administrative demands placed on them by the trials and a belief

that coordinated care would compromise their independence in treating their

patients. The GPs involved in the trials had different perceptions depending on

the model of care coordination used. GPs undertaking the role of care

coordinator had concerns about the time take to complete tasks associated with

coordinated care, the training required and the ‘time costs’ for any benefits

gained through the trials. GPs involved in care coordination where the tasks of

coordination were shared with others expressed some of these concerns, but were

generally more positive.[162]

4.30

Non-GP care coordinators

expressed concerns in relation to uneven workloads, their relationship with GPs

and the extent of their contribution to service coordination. Service providers

differed markedly in their perceptions of the trials. Some found that

coordination of care had freed them from case management, allowing them to focus

more on service provision, while others were concerned about increased

workloads and reduced resources.[163]

Substitution between services

4.31

An aim of the trials was to

promote further opportunities for appropriate substitution between acute and

sub-acute and community based services; community based services and

residential care; and a range of other community-based services.

4.32

The evaluation report stated

that the interpretation of service substitution varied across the trials. While

the majority of trials focussed on strategies to reduce hospital admissions,

the data do not indicate any effect on the rate of hospitalisation. Due to data

limitations it was not possible to establish whether any service substitution

had occurred.[164]

Range of services

4.33

The scope of pooling of

services can substantially influence the infrastructure costs of a trial. The

report noted that trials that pooled less widely than others, for example,

those that pooled only hospital, MBS and PBS have not demonstrated differences

in their ability to provide care within existing resources. The non-pooling of

residential care appears to have had an impact on a number of trials that have

anecdotal evidence of having delayed institutionalisation. The risk of cost

shifting by trials that pooled narrowly remains - however, there was no

evidence of this partly because the data were not available.[165]

Care coordination process

4.34

All trials demonstrated a

similar approach to the care coordination process which comprised assessment,

care planning, implementation, monitoring and review. How the various

components were put into operation varied according to the model of care

coordination within which they were placed. In all trials, GPs played a central

role, whether in the development of the care plans and/or implementation,

monitoring or review. Demand placed on GPs, both as a consequence of the trials

or external factors, restricted their capacity in some cases to be fully

involved in care coordination. Models in which GPs were supported in their

contribution to care coordination, through access to a care or service

coordinator, appeared to have been more satisfactory to all those involved in

the process.[166]

Financial outcomes

4.35

A ‘snapshot’ of the financial

status of each trial was made, and adjustments made for differences in

financial reporting and fund pool estimation. This analysis found diversity in

the way that trials allocated start-up and continuing costs, and also in the

way that the total costs of the trials were distinguished from running costs. A

comparison of trials’ total income with total expenditure, found that two

trials were significantly in deficit and one trial was slightly in deficit. The

report noted that, due to lack of data, conclusions about whether financial

decisions were appropriately made and key priorities chosen would need to be

considered in the final evaluation report.[167]

4.36

The report noted that there was

little evidence of coordinated care having an impact on the average cost or

distribution of services. For example, only one trial showed a statistically

significant reduction in the average cost of inpatient services. For a number

of trials, comparisons between the trial expenditure and the economic benchmark

(resources that would otherwise have been used), suggest that there are likely

to be gains made from coordinated care.[168]

Lessons from the trials

4.37

The evaluation report noted

that several key lessons emerged from the operation of the trials which are

outlined below:

-

coordinated care - funds pooling offers

potential advantages to facilitating care coordination for some, but not all

clients. This needs to be set against the considerable human and financial

resource costs associated with establishing and effectively managing the funds

pool. Improved targeting of people who need care coordination, and the

differentiation of care coordination approaches is also likely to be central in

maximising the value of coordinated care;

-

models of coordinated care - to be effective,

coordinated care requires a primary team approach, with GPs playing an important

and integral role. There needs to be a more systematic approach to coordinated

care in future trials, based on agreed eligibility criteria, better defined

target populations and standardised definitions of coordinated care and its

processes; and

-

role of GPs - given the pivotal role of GPs in

continuing care of patients with chronic conditions, the reasons why GPs choose

not to participate in the trials and the concerns expressed by participating

GPs need to be considered in the planning of future care coordination programs.[169]

Future directions

4.38

Some evidence suggested that

the coordinated care trials should be broadened in scope and extended in time

and coverage.[170] Professor Richardson

of the Centre for Health Program Evaluation (CHPE) suggested that the trials

could be broadened by extending the target population beyond persons with

complex chronic needs to the full population of a region. This would allow

preventive services to become a larger part of the model. But a longer time

frame would be required to test this type of model.[171]

4.39

Professor Hindle also argued

that it would be preferable to ‘run a demonstration project for an entire

community such the Hunter Valley or the ACT...it has to be a trial of the system

as it would operate in the real world and not where people can opt out, and so

on’.[172] NSW Health advised the

Committee that it is currently conducting a study into the feasibility of

introducing a funds pooling arrangement in two or three Area Health Services in

that State. Dr Picone from the Department stated that:

We think our area health services lend themselves more than in

some of the other states to allow this to happen because they have been running

for over a decade now...They are based on a population of people rather than on a

disease [model] because, if we go down the disease model, there is a chance of

reinforcing the lack of integration around the care of a human being that we

have got. The area health services have responsibility for the care of that

population and not just hospital care. Also, we have fairly sophisticated

funding arrangements.[173]

4.40

The Coordinated Care Trials

evaluation report also stated that extending the length of the trials would

increase the likelihood that effects such as reduced rates of hospitalisation

would be demonstrated within the time of the trial. The report also noted that

extending the trials would also reduce the average cost per client day and

improve the trials’ financial position, particularly for trials with

significant start-up costs.[174]

4.41

Professor Judith Dwyer representing

the Public Health Association of Australia argued that what was needed was a

‘move on from the second round of the coordinated care trials into some sort of

experimentation at the level of what kind of system you need to have in order

to deliver integrated or coordinated care, rather than simply looking at it at

the patient care level, which is what the coordinated care trials have done’.[175]

4.42

Professor Richardson suggested

that another option in relation to the trials would be to cover a more comprehensive

range of services and include, for instance, residential care, dental and

disability services. He argued that the reason for including residential care

is compelling because if care coordination reduces admission to residential

care facilities, the benefits of that should flow into the pool. The inclusion

of residential care would also increase the size of the pool, as many of the

chronically ill are also elderly. Extension to other areas is desirable, as the

aim is to break down program barriers and ensure access to care which is

appropriate to the health needs of the client group.[176]

Conclusion

4.43

The Committee notes the interim

evaluation reports on the coordinated care projects that have been published

and the various suggestions made to overcome the problems identified in the

initial evaluations. A full picture of the value of coordinated care and the

role it may play for specific groups or wider communities has not been possible

due to limitations in the data available from these studies. The Committee is

disappointed that the data from these initial evaluations is not more complete

and that conclusions about the effectiveness of the trials could not be drawn.

It is hoped that a more complete assessment of the trials will emerge when the

final studies are complete.

4.44

The Committee commends the

Government for committing to a second round of Coordinated Care Trials and

urges that work continue on developing the most suitable form of coordinated

care for Australian circumstances within the framework of Medicare. The

Committee believes that better data should be available and collected with the

additional trials to allow informed conclusions about the efficacy of these

trials to be drawn.

Recommendation 19: That Health Ministers ensure that the

additional Coordinated Care Trials be designed to include adequate and

appropriate data for collection and analysis to enable informed conclusions

about the effectiveness of these trials.