|

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page

Chapter 2 - Key Issues

The key issues

2.1 The boom in real estate and the large amounts of money involved in property investment attracted a number of unscrupulous operators, promoters and marketeers (generically called 'property spruikers' in this report) to the detriment of large numbers of consumers, and to the detriment of honest property investment advisers who lost potential business.

2.2 Significant problems associated with the provision of property investment advice and wealth creation training services in Australia today include:

- the variable quality of advice services, including concerns about the appropriateness, feasibility and, in some cases legal or ethical character of recommended investment strategies;

- the lack of disclosure of commissions and arrangements and relationships which promoters have with property developments;

- the lack of opportunity for consumers to have their questions answered, and to thoroughly consider a possible investment;

- misrepresentations that proposed investment strategies are risk-free or very low risk; and

- failure to provide promised refunds on seminars and courses and the difficulties consumers experience in obtaining redress.[1]

2.3 The key issue of this Inquiry is how to create a regulatory regime which takes reasonable steps to protect consumers from the operations of property spruikers and other get-rich-quick promoters, or, at the very least, establishes significant barriers to entry into this industry.

2.4 Property spruikers use a number of marketing tools, the most prominent of which in recent years has been the "wealth creation seminar", sometimes disguised as an "education program". Characteristics of their operations, generally, are:

- they target the financially vulnerable and unsophisticated;

- they use high pressure selling techniques;

- they promise much more than they can deliver;

- they involve undisclosed conflicts of interest; and

- they cost exorbitant amounts of money for what they provide.

2.5 Property spruikers have attracted considerable public interest particularly in times of booming property values, as experienced in most Australian cities in recent years. Precise numbers are not available, but it appears likely that many thousands of consumers have participated in these dubious schemes.[2]

2.6 As well as promoting the direct purchase of real estate, spruikers have also promoted other schemes such as the provision of funds to developers seeking additional capital, and the sale of educational, training and motivational courses and materials of the "How to be a property millionaire" type.

2.7 In August 2004 the Ministerial Council on Consumer Affairs (MCCA) released a comprehensive discussion paper on the issue of property investment advice, and invited submissions from interested parties. The Committee considered the MCCA discussion paper to be a good foundation for national policymaking on this issue, and decided to hold its own public inquiry into the regulation of property investment advice.

2.8 The MCCA discussion paper defines "advice" as broadly including information, opinions and recommendations where the adviser has a vested interest in, or hopes to obtain financial or other gain as a result of their recommendations, as well as the situation where the advice given can be described as genuinely independent or disinterested.[3]

2.9 As defined, advice about various aspects of property investment can be provided by a wide range of individuals and businesses, including real estate agents, property investment advisers such as buyers' agents, property developers and their sales consultants, financial planners, mortgage brokers, bankers and other lenders, accountants, lawyers, seminar operators and wealth creation promoters.

2.10 The Real Estate Institute of Australia (REIA) asserts that an important part of the issue is that property spruikers are not licensed real estate agents or certified salespeople and so have had no relevant training.[4] However, the Committee heard other evidence that suggested property spruikers often have a real estate background.[5]

Why is property investment advice important?

2.11 Australians have always had a high rate of home-ownership, and 'bricks and mortar' are also favoured for investment:

... the average Australian investor has more money tied up in directly held real estate investments than in directly held sharemarket investments.[6]

2.12 Australia's rate of home ownership is similar to some comparable countries, but it has a much higher rate of ownership of investment property. For example, about 70% of homes in Australia are owned or being purchased, compared with 69% in the United Kingdom, 67% in the United States and 64% in Canada. However, with regard to investment property, about 13% of Australian households receive rental income (up from about 9% a decade ago), compared with about 6.5% in both the USA and Canada, and 2% in the UK.[7]

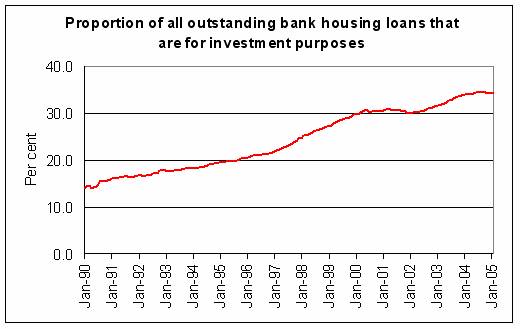

2.13 The continuing enthusiasm of Australians for property investment is shown in Figure 1. Investment loans as a proportion of total outstanding housing loans have grown from around 15% in 1990 to about 34% in 2005.

Fig.1: Proportion of bank housing loans for investment purposes

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletins.

2.14 Property is a very substantial part of the Australian economy. According to the submission from the REIA in the financial year 2002-03 property sales had a total value of $156 billion.[8] A significant proportion of Australians - estimated at 22% - rely for their housing on rental accommodation provided by private landlords.

2.15 The increasing interest in property investment is probably due to a combination of a number of factors such as the desire of investors to share in the significant capital gains made in the residential property market in recent years, the volatility of share markets, the collapse of major public companies such as Ansett and HIH, disappointing returns of superannuation funds, the availability of investment finance at relatively low rates of interest, greater variety of financing options[9], favourable taxation treatment; and the growing realisation that people must provide for themselves in retirement.

2.16 The vigorous marketing of property for investment in recent years (particularly off-the-plan sales and related financial products such as deposit bonds), has also no doubt contributed to generating greater public interest in this investment class.

2.17 Property is a very important asset class in Australia, yet the Committee found that the property investment advice profession seems poorly organised and developed when compared with other areas of investment advice such as, for example, the financial planning profession or stockbroking.

2.18 The Committee received evidence that suggested that Australians, perhaps as a result of their direct experience of home ownership, feel that they understand investing in 'bricks and mortar' and that it is somehow easier and safer than investing in other asset classes.[10]

2.19 Unfortunately many consumers have learnt, to their cost, that investment in property can be a complex matter, with considerable risks for the uninitiated. The amounts involved are usually relatively large, with significant entry and exit costs, and the risks involved in using some of the new financing options, such as utilising the equity in the family home, need to be well understood.

2.20 Professional property investment advice, personally delivered, is difficult to find although the REIA made the point that there are now many magazines and books on the market which provide advice on investment, including in property.[11]

2.21 Financial planners generally recommend managed investments to their clients as they derive their income from fees and trailing commissions. Mr J Hopkins of the Property Investment Association of Australia (PIAA) estimates that 'less than 1% of financial planners involve themselves in direct investment in property'.[12] The Financial Planning Association of Australia (FPA) admitted that 'Institutional licensees tend to prohibit recommending any direct property ... it is just too hard to monitor and control'.[13]

2.22 There is a small but growing sub-sector of the real estate industry which services investors interested in acquiring property. They are known as 'buyers' agents'.[14]

2.23 Buyers' agents appear to operate under a normal real estate agents licence, although their focus is on buying rather than selling property. While their business is helping buyers source investment property, they usually still obtain their fee or commission from the vendor.[15]

2.24 When the Committee pointed out that this seemed a conflict of interest, Mr Allen representing The Investors Club, who act as an agent for buyers, admitted that this was a dilemma for them. However, The Investors Club claims that its members/buyers pay no more than they would if purchasing the same property through a normal real estate agent—the vendor still pays a selling commission, but instead of paying it to his own agent the money is paid to the buyer's agent. Furthermore, in contrast with a normal real estate agent, The Investors Club says that it continues to provide its members/clients with a range of services after settlement takes place.[16]

2.25 In Australia, real estate agents have traditionally been paid by vendors.[17] Property buyers do not expect to pay for marketing or sales services related to real estate purchases, including property investment advice. That is why buyers' agents normally get their commissions from vendors even though they represent the buyer (i.e. their commission is built into the final selling price).

2.26 The REIA noted that buyers' agents 'are covered under the real estate legislation in each of the states and territories, with provisions for disclosure of any beneficial interest in properties, and also for cooling-off periods, which now exist in seven of the eight jurisdictions'.[18] However, buyers' agents often appear to provide investment advice, and the Committee was not convinced by the REIA's contention that buyers' agents are adequately regulated under present arrangements.

2.27 The booming property market and the fairly recent emergence of buyers' agents perhaps go some way towards explaining why property spruikers have succeeded in attracting such big audiences – potential investors want to know more about this important asset class, but there have been relatively few sources of recognised and readily-accessible information. So they turn to high-profile, apparently successful and very persuasive, property spruikers.

2.28 The Australian Consumers' Association (ACA) commented:

... there is strong pressure on consumers generally to provide for themselves financially in order to secure their future financial wealth, and particularly on those people approaching retirement. That is a very strong driver for people to attend these sorts of seminars and seek out financial information and investment advice wherever they can find it.

The reality is that these seminars are one of the few free mechanisms by which consumers access financial advice, and therefore it is little wonder they are drawn to them, not only by the promises of easy wealth but also because it is free for them to attend, certainly in the initial stage.[19]

2.29 The submission from Mr Vincent Mangioni of the University of Technology Sydney suggested that, to meet consumer needs, universities could develop and conduct property investment seminars.[20]

2.30 There is every indication that the interest of ordinary Australians in investing in property will continue to grow in the future. The Committee would like to see consumers provided with the best possible advice in relation to investment in this very important asset class, particularly so that the consumers are able to adequately weigh up the prospects for return on investment as against other asset classes available to investors.

2.31 This is particularly important with the retirement of the 'baby boomers' and the large amounts of superannuation money which they will have to invest. While the advent of superannuation choice on 1 July 2005 could provide consumers with more investment options, the submission from the Real Estate Consumer Association (RECA) warned of possible dangers:

With Super Choice almost ready to make its debut on the Australian financial markets, consumers will be incredibly vulnerable to a greater number of complex sophisticated scams without a properly constituted consumer protection agency ready to do whatever it takes to protect consumer interests.[21]

2.32 The property investment advisory industry is still in a formative stage and there has been no specialist industry association to develop codes of conduct and training courses such as exist, for example, for the financial planning profession. The submission from the Australian College of Financial Services (ACFS) reported that the Association of Financial Advisers recently adopted investment property advising as one of its disciplines, and has compiled a professional standard in that regard.[22] The submission from the fledgling PIAA indicates that an attempt to establish a specialist association for companies and individuals operating in the property investment industry is being made.[23]

2.33 The submission from Australian Property Systems makes the point that financial planners should provide their clients with advice covering all asset classes, based on the principle of balanced and diversified portfolios. However in practice financial planners focus on managed investments. Similarly, real estate agents and property marketing groups only recommend investment in property (and their advice is subject to various conflicts of interest). The submission argues that the solution is to include real property under FSR which will encourage all investment advisers to develop a good understanding of all asset classes.[24]

2.34 Given the public's obvious appetite for property investment, the Committee would ideally like to see the situation where all investment advisers, including financial planners, can provide professional advice on all asset classes, including real property. Until that ideal situation is achieved, there is obviously a need for a much better organised and properly trained group of advisers who can provide good advice on property investment. Chapter 3 of this report proposes new regulatory measures which, while providing some protection against property spruiking, also support the development of a legitimate, professional property investment advice industry.

How spruikers operate

2.35 The Committee received evidence outlining the normal modus operandi of property spruikers. Characteristics of their behaviour are:

- Spruikers allegedly often characterise their wealth creation seminars as educational seminars rather than as financial advice in order to avoid the regulatory requirements attracted by the provision of financial advice for a fee. In addition, by promoting a strategy rather than a particular investment, they argue that their activities are distinct from financial advice.

- Spruikers appear to use high-pressure, high-energy selling techniques in order to rush consumers into a decision without allowing them to give the decision adequate consideration. Subtle intimidation may also be used. In short, this is old fashioned hustling.

- Spruikers who do suggest specific investment opportunities are allegedly often paid a commission to promote those products. This provides an obvious conflict underlying the quality of information provided to consumers. This conflict is seldom if ever disclosed.

- Spruikers often supplement their incomes by obtaining fees and commissions from other sources (such as a "spotters fee" for finding particular properties). These fees are allegedly not disclosed appropriately.

- Spruikers allegedly either completely fail to discuss downside risks to the investments they promote, or aggressively downplay those risks.

2.36 RECA described typical spruiker activity as follows:

Consumers believe they are firstly purchasing an education course on money and investment strategies, how to manage risk, how to use stock market strategies AND, on how profits from the first year of the activity will pay for the extravagant course fees. People flock to learn how this is done under the mistaken belief promoted by the Group, that this is all Government Approved. Fear tactics are used to entice people to sign for a “on-the-night only discount offer, sweetened by a money back guarantee”...The whole structure is a con.[25]

2.37 The Committee is concerned that property spruikers often function both as property advisers and as credit brokers, arranging credit either for investment, or to pay for further "training".

2.38 For instance, spruikers may offer a "free introductory seminar" the purpose of which is to encourage people to enrol in the more expensive, substantive courses. Some spruikers offer personal loans or other credit facilities in order to "assist" consumers to afford these enrolment fees. Others offer to arrange financing for actual property purchases, including "vendor financing" and "deposit bond" arrangements where the borrower can be exposed to large financial risks, most of which are allegedly not adequately explained.

Why are spruikers able to operate?

2.39 Property spruikers appear to have been able to operate because the regulatory regime which governs property investment advice is not well defined. This is in contrast to investment advice on financial products, where the regulatory regime is very clearly defined.

2.40 The general consumer protection laws of the Commonwealth and States and Territories (including the Commonwealth Trade Practices Act 1974) are currently the principal laws regulating property and property investment advice.[26]

2.41 Only Queensland has introduced specific regulations relating to "property marketeers". A marketeer is defined as anyone directly or indirectly involved in any way in the sale or promotion of residential property, or the provision of a service in connection with a sale. This wide definition was meant to capture those on the periphery of the real estate industry who claimed that their promotional activities did not make them subject to the normal real estate laws.

2.42 The Queensland marketeer provisions prohibit misleading and deceptive conduct and false representations and various forms of offensive behaviour by marketeers in relation to the sale of residential property in Queensland.[27] However, while this law may have curtailed some of the excessive behaviour taking place in Queensland, the submission from Griffith University commented:

These provisions do not provide adequate consumer protection because of, in particular, their lack of licensing requirements and associated obligations.[28]

2.43 Other laws which may be relevant to aspects of property investment advice include State and Territory real estate and consumer credit laws — but these typically deal with operational issues rather than the provision of advice — and the Commonwealth Corporations Act 2001 which regulates, under Financial Services Reform (FSR)[29], advice on financial products. But real property is not considered to be a financial product, so advice related to investment in real property is excluded from the financial services laws.

2.44 The MCCA discussion paper provides the following 'formal' explanation for the exclusion of real property from FSR. With financial products (securities, derivatives, interests in superannuation funds and managed investment schemes, debentures, bonds etc) an investor surrenders day-to-day control of an amount of money or money's worth to another person who uses, or is intended to use, that money to generate a financial return for the investor. With direct investment in property, on the other hand, while the property itself may generate a return, it is not a return generated by the use of the investor's money by another person. [30]

2.45 Under this definition a clear distinction can be made between direct investment in property and investment in a property trust or managed investment. The latter form of investment is included under FSR as day-to-day control of the investor's funds is surrendered to a third person.

2.46 FSR may apply to a seminar presentation on property investment if, for example, the seminar presenter offers advice on shares as well as property, or if returns from property investment are compared with other asset classes, or if there is a discussion of credit or financing options.

2.47 The Australian Consumer and Competition Commission (ACCC) is the Commonwealth agency with responsibility for administering the Trade Practices Act, while the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) has responsibility for administering the Corporations Act and the ASIC Act.

2.48 So, at a Commonwealth level the ACCC has prime responsibility for regulating real estate advice and promotion and gets involved if misleading or deceptive conduct is alleged. ASIC may intervene if financial products or services are involved.

Limitations of general consumer laws

2.49 As outlined above, property investment advice is currently regulated under the general consumer laws (Trade Practices Act), unless a financial service is included when the Corporations Act or the ASIC Act may apply.

2.50 Some of the limitations of the general consumer protection laws are:

- they only allow corrective action to be taken after misconduct has occurred;

- they do not impose adequate barriers to entry into, or participation in, the industry (such as minimum training and educational qualifications, and fitness and propriety requirements);

- they do not stipulate that investors should receive advice which is of good quality and appropriate to their circumstances, and that all risks are to be clearly presented; and

- they do not contain a positive obligation to disclose conflicts of interest.

2.51 The MCCA discussion paper explains that enforcing general consumer protection laws can be problematic:

Unconscionable conduct-based litigation, in particular, is very resource-intensive and few cases have been undertaken. In the case of misleading conduct, and false and misleading representations, too, it can be difficult to establish misconduct, especially where the representations relate to future movements in property values or where there is any ambiguity about the falsity of claims made. These difficulties may limit the potential of the general consumer protection laws to deter rogues.[31]

2.52 The property spruikers have been able to utilise these limitations to their advantage. The MCCA discussion paper notes that the recent property boom has brought rogues and unscrupulous operators into the market, and the regulatory framework has posed few barriers to entry. It continues:

... there is evidence that rogue traders have been attracted to property investment promotion (as well as mortgage broking) from other areas of financial services that are, or have become, more highly regulated.[32]

Evidence presented to the Committee

2.53 The submission from the Law Institute of Victoria (LIV) noted the jurisdictional limitations of the various regulatory agencies under the current regime:

A conflict and crossover of jurisdiction exists between ASIC, ACCC and State-based consumer affairs departments. There is confusion over whether a Commonwealth or State level approach is warranted. This leads to each authority claiming it is the responsibility of the other authorities and leads to no regulatory authority taking any action and no provision of consumer assistance. Regulatory and prosecutory powers should be given to one specific authority to deal specifically with this type of behaviour.[33]

2.54 RECA commented that the ACCC was 'placed in an invidious position' in 1998 when ASIC was created and given responsibility for consumer protection in the area of financial services. To enhance the handling of complaints RECA recommends the creation of a National Consumer Protection Agency.[34]

2.55 The REIA believes that the current legislation and regulations are adequate, but have not been rigorously applied to property investment seminars.[35] When asked why Henry Kaye had managed to operate so long, the REIA replied:

What it boiled down to, we think, is that ASIC and the ACCC needed to be more assiduous—and I think they have now got the message in that regard. Rather than just wait for complaints, they have to be more proactive and trawl the marketplace. I am delighted to see ASIC taking some web sites to task because ‘Be a millionaire next Tuesday’ was clearly misrepresenting ...[36]

2.56 The Centre for Credit and Consumer Law at Griffith University commented:

As the current regulatory framework does not establish barriers to entry nor provide minimum standards of advice the consumer protective mechanisms are based on deterrence. In order for deterrence to be effective it is essential that the industry participants have an interest in an ongoing presence in the marketplace. This is not the case with some participants in the property investment advice industry.[37]

2.57 The National Institute of Accountants (NIA) suggested that gaps between State laws were to blame:

The problem with the current arrangements is not the federal laws, but the different state laws that govern this area. There are differences between the states in their legislation and in how they manage investment property advice. This lack of coordination makes it easy for unscrupulous advisors to seek the regime of least resistance. The heavy reliance of many state governments on the revenue raised from property taxes may also have caused some to be less rigorous in the application of law than might otherwise be expected.[38]

2.58 The submission from Wakelin Property Advisory suggested that lack of resources is an important issue for regulatory agencies:

... the ACCC does not have the resources to regularly monitor and take action against property investment advisers who mislead and deceive their clients. Take for example Henry Kaye and the National Investment Institute, who continued their operations largely uninterrupted for several years although some observers had little difficulty identifying their misleading and deceptive conduct.[39]

2.59 In responding to this comment, the Chairman of the ACCC indicated that the key issue was not resources, but that the ACCC can only act in a reactive manner. He also implied that demarcation with ASIC was a major factor at that time:

It is fair to say that we do have the resources to deal with these matters but, ultimately, they need to be drawn to our attention ... The process of enforcement of the law at the commission has been undergoing some change over recent times with a view to increasing the speed and effectiveness of the way we deal with these matters ... As soon as the [Robert G Allen] matter was drawn to our attention, within about three days we got to court and obtained interlocutory orders that provided for corrective material being placed at the seminar door.

In respect of Henry Kaye ... there was a period of time when this was a matter that we believed—and I think ASIC believed— needed to be dealt with by ASIC because it involved financial services. This is the complexity of dealing with financial services on the one hand and non-financial services on the other hand. What we got Henry Kaye on, I have to say to you, was nothing at all to do with what occurred within his seminar door. It was the advertisement for the seminar that promised to make property millionaires out of those attending his seminars. We did not focus on what occurred within the seminar door because, as you got within the door, as I have said on previous occasions, it probably fell outside the jurisdiction of the ACCC and into the jurisdiction of ASIC.[40]

2.60 In recent times the ACCC and ASIC have cooperated more closely in areas of overlapping jurisdiction, through the exchange of information, the referral of matters to the agency best placed to take it on, and the cross-delegation of powers. That cooperation was formalised with the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in December 2004. [41]

2.61 While the division of responsibility under the MOU has not changed substantially, the agreement clarified which aspects of property investment each agency would be responsible for and established procedures for a delegation of powers to each other. The division of responsibility is broadly as follows:

... the ACCC continues to pursue misleading and deceptive conduct in advertising and seminar content related primarily to property, while ASIC will take action in relation to misleading and deceptive advertising and content which is related to financial services, and to the offering of financial advice from a person not licensed to do so.[42]

2.62 During the public hearing, the ACCC described the approach the two agencies would take if a new spruiker started advertising:

Potentially, what happens is that we both start investigating. At some point, we obviously need to discuss with ASIC what we each make of it. Then perhaps—and this is where we start to lose time—we seek advice of senior counsel, which we have done on more than one occasion, on exactly where the jurisdiction is likely to fall and on what aspects. We then would reach some arrangement with ASIC as to how the matter would be pursued.[43]

2.63 The ACCC explained to the Committee that the cross-delegation of powers with ASIC has proven more effective than attempting joint actions. But delegations can only be case-specific and take time to put in place. Furthermore, sometimes is it problematic for an agency to work with delegated powers with which it is not totally familiar. The Chairman of ACCC summed up relations with ASIC as follows:

I would just like to emphasise that there is no lack of willingness or effort on the part of either ASIC or the ACCC to cooperate. It is working very effectively and we do that to the best of our ability. But inevitably when you are facing a prospect of going to court and having your jurisdiction challenged by the respondent to the matter, that is where I think both agencies can get themselves into some difficulty. They need to have some certainty as to their jurisdictional base.[44]

2.64 In the last eighteen months or so action by regulatory agencies has managed to rein in some of the worst excesses of property spruikers, but many consumers were burnt in the meantime.

2.65 The Committee notes that the number of property-related complaints received by agencies has fallen significantly,[45] which could be due as much to the cooling off of the property boom as to effective regulatory action. Nevertheless, many consumers became victims of spruikers during the boom, and there is clearly a need to close existing loopholes to make it difficult for spruikers to operate in the future. There is also a need to more clearly delineate the roles of the regulatory agencies. The ASIC submission admits the community is confused by the current division of responsibility. It commented:

There has been some confusion in the media and the community more generally about the extent of ASIC’s jurisdiction to regulate the activities of property investment advisers/promoters.[46]

Possible regulatory approaches

2.66 The Committee considers that the current regulatory regime in relation to property investment advice (primarily based on general consumer laws) is not able to provide an adequate level of protection for consumers, and should be strengthened.

2.67 Despite firmer action by the ACCC and ASIC in recent times, the reality is that spruikers, both for property investment and other get-rich-quick schemes, are still able to operate. The MCCA discussion paper notes that seminars are still being promoted and conducted, and there is evidence that marketing operations are continuing by other means as well. Mr J Allen of The Investors Club advised the Committee:

When I look at Saturday’s Courier Mail, for instance, there are still clearly unlicensed spruikers advertising every Saturday. They are still out there. The state legislation here has gone a long way in reducing their activity and some named players mentioned before have either fallen foul or have had their activities curtailed. It has not completely wiped it out in our view but it is certainly at much smaller levels than it was.[47]

2.68 RECA estimates that 80 spruikers have been active in the last 12 months. RECA advocates the creation of a dedicated National Consumer Protection Agency whose staff would comprise experienced fraud investigators as well as highly qualified forensic accounting specialists, law enforcement officers and consumer protection analysts.[48]

2.69 The ACA told the Committee:

... the attention on Henry Kaye has maybe had a bit of a dampening effect but the reality is people are still flocking to wealth creation seminars and these sorts of seminars and they are still paying up to $9,000—sometimes even more—to go on three-day seminars. I think in many instances they are doing it partly driven out of a desire to make a lot of money—that is a pretty understandable thing for people to want to do—but it is also that many people do not know where else to go. They have been told they have to provide for their future financial security by investing and they do not know enough about it to be discerning.[49]

2.70 The submission from Griffith University urged the Commonwealth to take action:

As consumers are extremely vulnerable to fraudulent, negligent or inappropriate provision of advice and there is a significant risk of the loss of large amounts of money or even the loss of the major asset of the family home, we strongly support government intervention in relation to the property investment industry by the inclusion of the provision of property investment advice in the financial services regulatory framework.[50]

2.71 The LIV recommends a coordinated regulatory regime to address the deficiencies in regulation, as evidenced by the numerous property investor schemes that continue to flourish with little consumer recourse available.[51] In regard to this situation the LIV recommended:

... an authority (whether an existing authority or a new authority) should be given specific powers and authority to regulate the property investment advice industry and to prosecute persons involved in unconscionable behaviour. Specific direction needs to be given to avoid the existing problem of regulatory authorities declining to act because of perceived demarcation issues.[52]

2.72 The FPA commented that, although the number of scams appears to have decreased as the property boom has cooled, action needs to be taken now to ensure they cannot occur again in the next boom:

With the current slowdown in the property market, many of the schemes and promotions which were of concern appear to have faded away. With the inevitable upturn in the property cycle—whenever that may be—unless the opportunity is taken now to correct the shortcomings of the regulatory regime for property investment advice, investors will once again be vulnerable to unscrupulous operators. The FPA would urge that the momentum for reform be maintained.[53]

2.73 ASIC's submission doubts that general consumer protection laws can adequately protect consumers because they cannot force disclosures nor ensure the provision of quality and appropriate advice:

... it has been common for property promoters to present themselves as disinterested providers of investor education and other services and, as part of this, to fail to disclose interests they have in properties 'introduced' to seminar attendees, or fees and commissions received for promoting particular developments. Under the general consumer protection laws there are, we would suggest, few regulatory incentives for promoters to make these positive disclosures. [54]

2.74 ASIC argues that there is 'market failure' and that corrective action is needed:

... we believe that the existing regulatory regime has not proven sufficient to deal with the worst excesses that we have seen and that it is not simply a matter of more vigorous enforcement. We believe that some changes are required.[55]

2.75 ASIC notes that spruikers can enter the property market relatively easily:

... if the share market is booming, then marginal/spruiker/dishonest elements cannot just move into giving advice about equities. There is a whole set of requirements that they have to meet, so there are some barriers to entry that it was government policy to put in place. [In contrast] If the property market is booming then people with no particular training qualifications, who are just spruiking, can set up shop quite easily. There are no effective barriers to entry.[56]

2.76 The ACCC agues that, while its use of the TPA powers has been reasonably successful, a more effective regulatory approach would be to allow both the ACCC and ASIC to operate with a full range of concurrent legislative powers because:

... the reality is that conduct may involve a combination of factors which may contravene both TPA and ASIC provisions (seminars often provide information on both property matters and financial matters such as mortgages). Hence, it is not always clear, to the regulators or even the regulated, as to who is to deal with such conduct.[57]

2.77 The ACCC contends that overlapping the jurisdictional reaches of both regulators would allow either agency to react promptly and confidently, without the need to arrange cross-delegation of powers or to face procedural uncertainty in the Courts. That would be, from the ACCC's point of view, a more effective solution than including real property under FSR.[58]

2.78 The Committee finds considerable merit in the ACCC's recommendation and feels that concurrent legislative powers would probably have enabled quicker and more decisive action against the property spruikers in the past. However, the Committee notes a MOU was signed between the ACCC and ASIC in December 2004, and the expectation by the two agencies that the MOU will enable them to react to situations much more quickly and decisively.

2.79 The Committee would like to assess the practical outcomes of the MOU over a reasonable period of time. If the outcomes are as positive as the agencies expect, then concurrent legislative powers may not be necessary.

2.80 After reviewing the available evidence, the Committee has decided that the most efficient and effective solution to ensuring the provision of good quality property investment advice is the creation of a separate asset class under FSR (see Chapter 3 for details). If this recommendation is accepted by Government, its impact should be assessed after a period of operation, to ensure that it is working as intended.

Is industry self-regulation appropriate?

2.81 Some submissions, such as from the PIAA, argued in favour of industry self-regulation.[59] But most submissions felt that company or industry self-regulation would not be appropriate to this industry. For example, the submission from the REIA commented:

...the REIA does not support voluntary codes – while it is highly likely that REIA members would endeavour to adhere to a voluntary industry code, there is no guarantee that rogue marketers who were not members of REIA would adhere to such codes. Property investment advice cuts across various industry sectors and professional and trade groups, and a proportion of promoters are ‘fly by night’ operators without an industry position or reputation to maintain ... While the industry association might be able to regulate compliance amongst its members, it cannot be responsible for non-members whose actions might reflect negatively upon complying members.[60]

2.82 The LIV commented that 'self-regulation is not appropriate in the case of aggressive property promoters'.[61] The Accounting Bodies commented:

Given the nature of scams that have emerged with the likes of Henry Kaye and others, it is probably fair to say that the regulation ought to be at a government or quasi-government level on the basis that it is unlikely that any form of self-regulation will have the desired effect.[62]

2.83 The ACA felt that self-regulation would not provide sufficient protection for consumers:

Just looking at how the sector has operated, it has markedly failed to demonstrate it could self-regulate to an adequate standard of consumer protection.[63]

2.84 Griffith University was definitely against self regulation:

Self-regulation is not appropriate for this industry as there is no cohesive industry body, some firms have no interest in ongoing reputation and there are low barriers to market entry thereby permitting easy access to the market.[64]

2.85 The NIA does not believe that self-regulation is appropriate at this stage:

The industry is one that appears to be, at least by certain sectors, focused on their own short-term interests and not the interests of the community at large. The NIA, therefore, does not believe that self-regulation would be suitable for property investment advisors, not at least in the current environment. The development of a set of national rules and regulation of property investment advisors may in the future lead to an environment where greater self-regulation may be possible, but currently the NIA believes that such a scheme would not be viable and not be in consumers’ best interests.

2.86 It may be that at some future point, industry self regulation is a viable proposition. However, the Committee agrees with the view that self-regulation would be premature at this time. Accordingly, Chapter 3 proposes regulatory measures which will have the effect of supporting the industry's development and reducing competition from illegitimate property spruikers.

Commonwealth or State responsibility?

2.87 Virtually all submissions supported the view that the regulation of property investment advice needs to be nationally consistent, so that the same law applies across all jurisdictions. In that context, most submissions favoured making this a Commonwealth responsibility.

2.88 It was suggested that the fact that property spruikers normally operate across State and Territory boundaries had made it more difficult for regulatory agencies to target unscrupulous behaviour.

2.89 The LIV noted that it is common for transactions involving property to cross State boundaries, and endorsed a Federal approach to regulation.[65] The Law Council of Australia (LCA) supported 'Commonwealth legislation and the uniform administration of property investment advice laws by ASIC'.[66]

2.90 The PIAA pointed out that in the property marketplace 'you can have a property developer in one State, a financier in another State, and the investor somewhere else'.[67] They called for a regulatory regime "...where the property investment advice law works across Australia with no possibility of variation in any State."[68]

2.91 Griffith University supported Commonwealth regulation 'due to the transient nature of some of the members of the industry, and the similarity of the industry to the financial services market'. Employing uniform state and territory legislation would involve the creation of a whole new framework, whereas it would be more efficient to include real property under FSR.[69]

2.92 The FPA advocated a national approach, under ASIC:

... the FPA considers that it would be more efficient if the national regime was achieved by Commonwealth legislation rather than by a coordinated uniform approach. As financial services are governed by national legislation it would be logical that the counterpart regime for property investment advice be similarly regulated, with ASIC as the regulatory authority.[70]

2.93 The ACA argued that a regulatory regime must be nationally consistent. Their preference is for regulation by the Commonwealth, but if that is not possible, there should be uniform regulation (and enforcement processes) across all States and Territories.[71]

2.94 The NIA said that, while Commonwealth legislation would give the best outcome, it believes that current constitutional arrangements mean that there would be the constant threat of challenge. The NIA suggested that uniform State legislation would be the most practical option:

The NIA’s preference is for a model based on a framework of uniform state legislation with referral of enforcement activities to a federal authority (ASIC). The Constitutional reality is that most of the powers in relation to property investment advice reside with the state and territory governments ... [would] prevent the current situation of regulatory arbitrage, where differences in state laws are used to get around the law.[72]

2.95 The Commercial Law Association of Australia (CLAA) suggested that the regulation of property investment advice should be on a uniform State-by-State basis which 'would be consistent with the existing constitutional and fiscal framework'.[73]

2.96 The Committee agrees that there is a strong case for a national approach to any new regulation of property investment advice. Property investment is of interest to consumers across Australia, and they should all be able to receive similar treatment and protection wherever they reside. The Committee considers that can best be achieved through making this matter a Commonwealth responsibility.

Recommendation 1

2.97 The Committee recommends that the regulation of property investment advice, but not of real property or real estate transactions generally, should be a Commonwealth responsibility.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page

Top

|