| 3.1 |

The Committee’s roundtable hearing was divided into two sessions. The first session was titled Progress to date and current operational priorities. The second session was titled Emerging lessons. While there was some overlap of issues across the two themes, this basic structure helped to keep discussions focussed. |

| 3.2 |

This chapter highlights some of the main topics to emerge from each session. |

|

|

Session 1 – Progress to date and current operational priorities |

Context |

Scale |

| 3.3 |

At the hearing, many witnesses alluded to the sheer scale of the tsunami, both in terms of its impact on communities and the challenges posed to those involved in the humanitarian response. |

| 3.4 |

Rear Admiral Moffitt, of the ADF provided a vivid first-hand account of the impact of the earthquake in Banda Aceh:

…This was a war zone before it became a disaster zone…If you have not been there, I do not believe you can have the vaguest comprehension of what this was like. Even experience in Cyclone Tracy would not really prepare you for what this was like…The town was divided into four zones…There was structural damage from beginning to end across the entire expanse of the town of some 350,000 occupants…[In some zones] entire houses were reduced to concrete slabs…the only things standing were a few of the tens of thousands of palm trees that had been there before…within the first two zones there were tens of thousands of bodies…1

|

| 3.5 |

Mr Tickner of the Australian Red Cross remarked,

I was thinking the other day of challenges that the organisation has confronted in its 91 years of existence. Probably you would rank the First World War and the Second World War and then the tsunami. It is that big.2

|

| 3.6 |

Underscoring these comments, Dr Glasser of CARE Australia said that,

Every aspect of the humanitarian response has to be viewed in the context of the huge scale of the disaster-staffing, coordination, logistics, the timeliness of the response and even assumptions about the funding that was available for our responses.3

|

Complex operating environment |

| 3.7 |

Federal Agent Kent gave an account of the conditions under which the AFP set up the DVI mission in Thailand:

We made strong recommendations early that we should try to consolidate all the deceased at a single point in Phuket, preferably near the airport- for logistical reasons and to facilitate a more rapid identification…That was a key efficiency.

However, there were sound cultural and practical reasons why the Thai government could not agree to that…[the people from the northern provinces were poor…to some of them that journey–to collect their loved ones- would have represented four months salary…That meant we had to extend our supply chains across hundreds of kilometres. We had to set up not one but four mortuaries and supply them with staff and resources.4

|

| 3.8 |

ACFID relayed the situation which confronted its member NGOs in Indonesia:

I would also point out that dealing with multiple layers of government and with communities that had lost leadership-particularly in Aceh, where so many people had been killed, including community leaders-made this very complex.5

|

| 3.9 |

AusAID added,

…a lot of things were more complex than any of us assumed in this environment, and of course no one had practice on this scale.6

|

Increased frequency of natural disasters |

| 3.10 |

Statistics from the UN Office of the Special Envoy for Tsunami Recovery indicate that the frequency of natural disasters is increasing:

2005 was a record year for natural disasters with 27 named storms, 15 hurricanes and three category five hurricanes. Nearly 97, 000 people died (78, 000 of these in the Pakistan earthquake), 133 million people were affected and economic losses of $220 billion were incurred (with Hurricane Katrina accounting for 78% of the economic costs).7

|

| 3.11 |

Witnesses commented on the strain that major disasters occurring in sequence were placing on the humanitarian system. Dr Glasser of CARE Australia noted that had the recent South Asian ( Pakistan) earthquake occurred closer to the Boxing Day tsunami, rather than months later, the aid community “would have been absolutely overwhelmed.”8

|

|

|

Transparency and accountability |

| 3.12 |

From the outset, the umbrella organisation for Australian NGOs, ACFID (the Australian Council for International Development) undertook to publish quarterly reports on expenditure and progress. Similarly, AusAID produced regular progress reports. |

| 3.13 |

So far, ACFID has issued four quarterly reports which can be downloaded from the ACFID website.9 AusAID has released three reports, the first of which focused on the emergency phase of the relief effort, the latter two concentrate on the reconstruction phases. The most recent report focuses on assistance to Indonesia. These reports can be found on the AusAID website.10

|

Overhead costs |

| 3.14 |

Back in January 2005, ACFID issued a pledge to keep administration costs as low as possible, to 10 per cent or less.11 Observing that a recent ACFID report had shown that overhead costs averaged about 3.3%, the Committee sought information as to how this compared to other relief efforts.12

|

| 3.15 |

ACFID responded that the tsunami was a unique event and there was probably no comparison point, however,

the evidence through our four quarterly reports indicate that there has been quite a considerable achievement to that end.13

|

| 3.16 |

While it is clear from a donor perspective that administration and labour costs should be kept to a minimum in humanitarian operations, agencies stressed that this should not be at the expense of driving projects forward and achieving quality outcomes on the ground for beneficiaries.14

|

|

|

Rate of expenditure |

| 3.17 |

The Committee said that some members of the public had voiced concerns about where their money was being spent. The Committee invited the agencies present at the hearing to comment on whether they had been slower to spend the money than raise it.15

|

| 3.18 |

CARE Australia, ACFID, Caritas Australia and Oxfam Australia advised the Committee that they had spent in the region of 45-60% of donor funds to date.16

|

| 3.19 |

Participants acknowledged the frustration felt generally at how much more needed to be achieved, but noted also that the completion of the reconstruction and development phase needed to realistically be viewed in terms of years, rather than weeks or months.17

…much more could be spent on quick but rash spending but there is obviously a commitment not to do that…this is going to take a long time and we need to do it properly.18

|

| 3.20 |

During the hearing, the Committee questioned AusAID on the status of the Australian government’s commitment to deliver $500 million in grants and $500 million in concessional loans to Indonesia, via the AIPRD.19 AusAID replied that, thus far, the government had focused expenditure on immediate needs, including food aid, shelter, health and education, rather than the loans component of the AIPRD. AusAID explained that the infrastructure loans component of the AIPRD was a longer term initiative given the time required to develop major infrastructure programs. That said, the government had already funded work through the UNDP to rebuild the port in Banda Aceh.20

|

|

|

Housing |

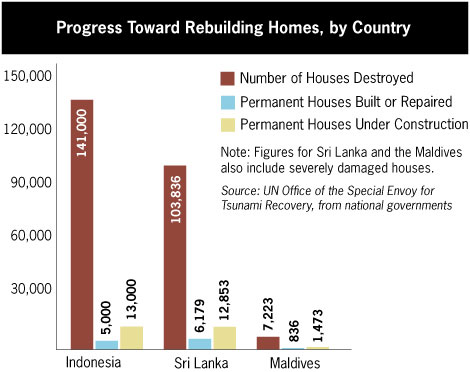

| 3.21 |

As the graph below illustrates, the rebuilding of homes across the tsunami-affected countries has been relatively slow.

Source Foreign Policy Magazine |

| 3.22 |

Similarly, as of December 2005, only a small percentage of schools and health clinics had been rebuilt:

In Indonesia’s Aceh and Nias where 2132 schools were destroyed or damaged, 84 permanent and semi-permanent schools have been built. More than 400 health centres were also destroyed, with 132 temporary health clinics since built in their place.21

|

| 3.23 |

The issue of rebuilding is clearly “the priority” and the Committee wanted to hear about the particular difficulties that agencies were experiencing and to what extent these are being overcome. |

| 3.24 |

Witnesses expanded on factors which are continuing to hamper the reconstruction phase, such as:

- the local inflation rate of 40% in Aceh, in part caused by the response, and the effect this is having in driving up labour, materials and transport costs;22

- (for instance, the cost of building a house has effectively doubled)23

- difficulties in obtaining sufficient supplies of sustainable and legal plantation timber;24

- labour shortages, with competition for staff amongst NGOs and the BRR;25

- the laborious processes of re-issuing lost identity cards and land title documentation, and processing compensation claims;26

- delays in agreement over transitional housing strategies;27 and

- the remoteness of some communities.28

|

| 3.25 |

In spite of these very significant challenges, agencies reported making some progress on rebuilding homes.29

|

| 3.26 |

AusAID recounted that its reconstruction efforts were focused on Aceh and it was closely monitoring the speed of rebuilding with its NGO partners.30

|

|

|

Corruption |

| 3.27 |

Various concerns about the effectiveness of aid delivery31 and the misappropriation of aid funds have been voiced in the media in recent months.32 Oxfam Australia told the Committee that it had recently conducted a fraud investigation which concluded that approximately $US 29,000 of Oxfam funds had been used inappropriately.33

|

| 3.28 |

At the hearing, the Committee explored the subject of corruption with witnesses. |

| 3.29 |

A number of agencies commented on the issue, with reference to stories from the field. Agencies agreed that corruption was an ongoing challenge for them all:

Although we are all accredited with systems for managing fraud and every aspect of corruption, no system is perfect so you hope that the systems you have put in place are going to catch the key issues…In this case, Oxfam’s system caught something...It takes both good systems and very experienced people to manage it effectively. 34

|

| 3.30 |

AusAID emphasised that both the Indonesian and Australian governments are committed to addressing the problems of corruption. AusAID outlined a number of initiatives in this regard, including working with the Supreme Audit Agency on their assessment of irregularities in the administration of emergency funds and in a broader sense, strengthening central government agencies.35

|

|

|

Session 2 – Emerging lessons |

Community-based approaches |

| 3.31 |

At the roundtable, members and witnesses discussed how agencies determine their assistance in consultation with the local community. AusAID communicated their process of training over 600 village leaders [in Indonesia] to help with the planning of village reconstruction and direct access assistance.36 AusAID acknowledged that these processes could lengthen the rebuilding phase.37

|

| 3.32 |

ACFID reiterated the importance of community-based approaches:

That has certainly been key in all the work of our member agencies because, essentially, doing this in a completely top down way, apart from the immediate survival aspects for survivors, tends to be a very ineffective way of bringing the community together again.38

|

Acknowledging local resources |

| 3.33 |

A number of witnesses wished to have placed on the record the effort of Indonesian people to assist themselves. Rear Admiral Moffitt of the ADF said that was something that Australians needed to recognise and give much more credit for:

In comparison with what we did, particularly in the area in which Australian Defence Force members worked physically, they overshadowed our effort phenomenally…They were exceptional in spirit, and, given the circumstances, their stoicism was unbelievable.39

|

| 3.34 |

Mr Isbister of Caritas Australia endorsed the Rear Admiral’s comments and reported a strong network of doctors from Yogyakarta operating the clinics and hospitals in Malabu shortly after the disaster.40

|

Cultural sensitivity |

| 3.35 |

When the AFP described its DVI operation in Thailand to the Committee, it was apparent that cultural sensitivity was key.41 Rear Admiral Moffitt provided further examples of instances where Australian personnel had made the effort to observe local ways and noted,

…the degree of sensitivity Australians can show when they go into these circumstances is one of the great assets that we take with us.42

|

Women |

| 3.36 |

Committee members and agencies acknowledged that women play a vital role in getting communities back up and running again. Accordingly, women require appropriate support services. |

| 3.37 |

Dr Glasser of CARE Australia stated that,

...it has been demonstrated time and time again that women play a fundamental role in resolving conflict and building peace.43

|

| 3.38 |

AusAID noted that of the 600 village leaders being trained to assist with rebuilding, over 300 of those were women.44

|

| 3.39 |

The Committee questioned AusAID about what counselling was available to women following the tsunami.45

|

| 3.40 |

AusAID informed the Committee,

We have been funding an NGO to work in Aceh to help build up capacity for counselling…46

|

| 3.41 |

Subsequent to the hearing, AusAID supplied the Committee with additional material on a range of programs and initiatives it has in place to assist women in Aceh, in respect of trauma awareness and counselling, and also improving services in the areas of reproductive health and maternal child health.47

|

|

|

Media and public education |

| 3.42 |

The Committee wanted to discuss the role the media had played in determining public perceptions about whether tsunami response funds were being spent appropriately. Participants agreed that media reports were not always accurate or conducive to what agencies were trying to achieve. |

| 3.43 |

Oxfam told the Committee that it had made a conscious decision early on in the fraud investigation to be proactive, and had contacted journalists with the facts in order to prevent inaccurate reporting. This strategy had resulted in an initially sympathetic media response.48

|

| 3.44 |

AusAID described a similar proactive approach which it had taken with the media. Anticipating that there might be negative press, particularly in the area of housing, where there has been a number of well-documented problems, and as the tsunami response neared its one year anniversary, it invited a group of journalists from both Australian television and print media to come to Aceh. It was hoped that with full access to all of AusAID’s projects, journalists could appreciate the multi-faceted nature of undertaking development in the Aceh context.49

|

| 3.45 |

AusAID noted that it had recently extended a similar invitation to a number of Indonesian journalists to encourage greater positive coverage in the Indonesian media as well and this had been successful.50

|

|

|

Inter-agency collaboration |

| 3.46 |

Several NGOs placed on the record their appreciation for the support they received from the government. ACFID summarised the sentiment:

We really welcomed the Australian government’s close collaboration with our member agencies and our council. This was one of those instances where Australia Inc., so to speak really came through.51

|

| 3.47 |

However, ACFID observed that for future operations, it would be better to have the government and NGOS present as a united front, with joint statements and so forth, at the beginning phase of the crisis, rather than the middle phase as was the case with the tsunami response.52

|

Civil-military cooperation |

| 3.48 |

ACFID told the Committee that although NGOs had a good working relationship with the ADF at senior levels, there was still much to be gained from greater interchange between civil and military organisations:

We participate in a number of training activities. We have a generally good dialogue, but we simply do not have enough understanding of one another of how the forces operate and vice versa. That is something we need to do jointly in our own way.53

|

Formalised agreements |

| 3.49 |

The AFP noted that there was no formalised agreement between Australia and Thailand regarding the Australian-led DVI operation there, and it may be helpful to have a more formal arrangement in place for future operations.54

|

|

|

Lifting the bar of accountability |

| 3.50 |

ACFID told the Committee that Australia was the only country in the world,

that did a consolidated NGO public accounting exercise.55

|

| 3.51 |

CARE Australia indicated that the joint reporting process had ‘lifted the accountability bar’ amongst NGOs and encouraged agencies to have robust discussions amongst themselves and with ACFID about costs.56

|

Disaster preparedness |

| 3.52 |

Linked to the earlier observations about the increasing incidence of natural disasters, witnesses alluded to the need to strengthen the standing capacity of the international aid community to respond to future humanitarian emergencies.57

|

| 3.53 |

Oxfam and World Vision referred to the difficulties of recruiting and retaining suitably experienced staff.58 The Red Cross echoed their concerns:

We need to reach out…to a whole range of professions in order to build our volunteer base in the case of external emergencies…59

|

| 3.54 |

With funding from the Gates Foundation, an international working group has been formed to examine issues such as humanitarian staffing capacity.60 Other disaster preparedness initiatives referred to at the hearing include the Red Cross movements’ examination of International Disaster Response Laws (IDRL).61 Following the hearing, the Red Cross provided the Committee with some information on this project.62

|

| 3.55 |

Above all, witnesses spoke about the need to have sufficient funds on stand-by for the international community’s initial response to future emergencies. The AFP described the frustrations and delays it experienced in trying to procure financial support from other nations for the DVI mission in Thailand. 63

|

| 3.56 |

Mr Neill Wright, from UNHCR, noted that his agency’s central emergency revolving fund- to which Australia had contributed - had been strengthened.64

|

Formal evaluations |

| 3.57 |

At the hearing, AusAID advised the Committee that the agency was formalising a formal evaluation of AusAID’s response to the Indian Ocean tsunami, and the roundtable hearing would provide important input to that process.65 |

|

|

The Committee’s views |

| 3.58 |

The Committee found the roundtable discussions on Australia’s response to the tsunami extremely valuable. Feedback from the witnesses, both at and after the hearing, indicated that they too found the sessions both informative and illuminating. |

| 3.59 |

Throughout the course of the morning, the Committee heard agencies express their disappointment about how a few negative stories about the tsunami response in the press seemed to take precedence over the many positive stories that could be told. At the hearing, the Committee was pleased to hear some of the many good stories agencies which had to tell. The Committee was affected by the shared experiences of agencies, and particularly, those of the ADF and AFP personnel who were involved in the initial clean-up and DVI missions. Officers clearly carried out their jobs with compassion and dignity under exceptionally difficult and quite overwhelming circumstances - and this is something that those individuals and all Australians can be proud of. |

| 3.60 |

The Committee would like to see more coverage of the reconstruction effort as it progresses, disseminated through the Australian media and both government and NGO agencies’ publications and websites. Clearly, the tsunami is no longer considered “front page news.” It took place some 18 months ago and has been superseded by a sequence of other distressing natural disasters. That said, it remains the largest international relief and reconstruction effort staged in modern times and one to which Australia continues to contribute significant resources. |

| 3.61 |

The Committee recognises that the frequency of natural disasters appears to be on the rise in the region and worldwide and heeds the humanitarian community’s concerns about being stretched to capacity. |

| 3.62 |

The Committee endorses the government’s plan to enhance its emergency response capacity, as outlined in the AusAID white paper.66

|

| 3.63 |

The Committee notes AusAID’s intention to formally evaluate its response to the tsunami in the near future. The Committee looks forward to learning the outcomes of that evaluation. |

| 3.64 |

The Committee encourages AusAID and ACFID to continue with their regular progress reports on the tsunami response for as long as Australia remains involved in post-tsunami rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts.

Senator A B Ferguson

Chair

22 June 2006 |

| 1 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, pp. 20-21 Back |

| 2 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 9 Back |

| 3 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 3 Back |

| 4 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 32 Back |

| 5 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 8 Back |

| 6 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p, 25 Back |

| 7 |

UN Office of the Special Envoy for Tsunami Recovery website Back |

| 8 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 4 Back |

| 9 |

ACFID website, www.acfid.org.au Back |

| 10 |

AusAID website, www.ausaid.gov.au Back |

| 11 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 9 and p. 10 Back |

| 12 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 8 Back |

| 13 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p.9 Back |

| 14 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 10 Back |

| 15 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 10 Back |

| 16 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, pp. 11-15 Back |

| 17 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 15 Back |

| 18 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 10 Back |

| 19 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 10 Back |

| 20 |

Official transcript of Evidence, p. 13 Back |

| 21 |

The Tsunami A Year On , Insight, The Age, Christmas edition 2005, p. 16 Back |

| 22 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, pp. 23 -25 Back |

| 23 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 24 Back |

| 24 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, pp. 22 - 24 Back |

| 25 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 22 and p. 23 Back |

| 26 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 23 & p. 25 Back |

| 27 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 25 Back |

| 28 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 11 Back |

| 29 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 22 Back |

| 30 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p, 5 Back |

| 31 |

See Aid Watch, A People’s Agenda? Post-tsunami Reconstruction in Aceh, Feb 2006 Back |

| 32 |

See Waves of Corruption, The Australian, 24 April 2006 Back |

| 33 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 29 Back |

| 34 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 27 Back |

| 35 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 26 Back |

| 36 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 5 Back |

| 37 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 5 Back |

| 38 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 7 Back |

| 39 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 21 Back |

| 40 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 22 Back |

| 41 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 32 Back |

| 42 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, pp. 39- 40 Back |

| 43 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 36 Back |

| 44 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 35 Back |

| 45 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 37 Back |

| 46 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 37 Back |

| 47 |

Exhibit 2, Supplementary information from AusAID on services for women in Aceh. Back |

| 48 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 29 Back |

| 49 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 29 Back |

| 50 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 29 Back |

| 51 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 7 Back |

| 52 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 40 Back |

| 53 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 41 Back |

| 54 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 33 Back |

| 55 |

Offiicial Transcript of Evidence, p. 41 Back |

| 56 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 9 Back |

| 57 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 4 & p. 39 Back |

| 58 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 22 & p. 38 Back |

| 59 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 39 Back |

| 60 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 38 Back |

| 61 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 34 Back |

| 62 |

Exhibit 1, Australian Red Cross, Supplementary information on International Disaster Response Laws, Rules and Principles (IDRL). Back |

| 63 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 33 Back |

| 64 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 38 Back |

| 65 |

Official Transcript of Evidence, p. 6 Back |

| 66 |

See Australian Aid: Promoting Growth and Stability, A White Paper on the Australian Government’s Overseas Aid Program, p. 46, available from the AusAID website http://www.ausaid.gov.au/publications/pubout.cfm?Id=6184_6346_7334_4045_8043 Back |