Finance and responsible government

The true ‘lion in the path of Federation’ was the extent of the Senate’s powers in relation to bills imposing taxation and appropriating money (money bills) and, in particular, whether the Senate should be able to amend them. It was generally accepted throughout the conventions of 1891 and 1897–8 that the Senate should be able to initiate and amend any type of bill except a money bill, and that it should be able to reject any bill.

Intertwined with this issue were broader concerns about the compatibility of ‘responsible government’ with federation. ‘Responsible government’ meant the system of government which had evolved in Great Britain, where the government was responsible solely to the popularly-elected House of Commons. Governments were formed and removed in accordance with the party numbers in that house. The other chamber, the unelected House of Lords, played no part in that process. In particular, it could not originate or amend money bills. (This was a matter of convention until it was made a matter of law in 1911.)

Money bills lie at the heart of government. Taxation bills raise revenue and appropriation bills authorise the government to spend that revenue. If the necessary revenue is not raised by the Parliament, or if the authorisation to spend revenue on proposed activities is not given by the Parliament, the proposed activities cannot be undertaken by the government. Ultimately then, the power to originate and amend money bills is the power to control the activities of the government.

The problem for the delegates at the 1891 and 1897–8 conventions was as follows. In Australia, the adoption of full British responsible government would have meant making the government responsible solely to the House of Representatives. Delegates from the larger colonies argued that this could only occur if that house, like the House of Commons, possessed the exclusive power to originate and amend money bills and, consequently, the exclusive power to control the activities of government.

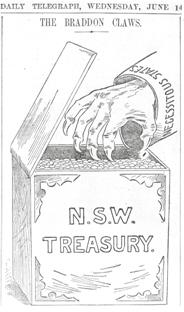

Image: National Library of Australia

In support of their demands for British responsible government, the delegates emphasised that most of the members of the House of Representatives would come from the larger states whose taxpayers would provide most of the revenue for the activities of the government. Richard O’Connor of New South Wales put it bluntly:

No body of people outnumbering the population of the smaller States as they do would put up with their dictation on such a matter as the expenditure of their money.

Convention Debates, Adelaide, 13 April 1897

These delegates argued that the Senate should only have the right, ‘to be exercised in some great emergency’, to reject money bills outright.

On the other side, Sir John Forrest of Western Australia, protested that, if the power to amend money bills was not granted to the Senate:

we may as well hand ourselves over, body and soul, to those colonies with larger populations.

Convention Debates, Adelaide, 13 April 1897

He and other delegates from the smaller colonies feared that the proposed federal government could act to the detriment of their states unless the Senate, most of whose members would come from the smaller states, possessed this power.

To grant the Senate the power to amend money bills would, however, have given it constitutional powers in relation to the government nearly the equal to those possessed by the House of Representatives. As many delegates from both large and small colonies recognised, this would make the government responsible to both houses of Parliament. Deadlocks on money bills would inevitably arise, during which the government would be paralysed.

Sir John Downer, Edmund Barton and Richard O’Connor, drafting committee of the Australian Constitution appointed during the Federal Convention, Adelaide, 1897. Image: National Library of Australia

The delegates to the 1891 convention responded to this dilemma in two ways. First, they did not mandate responsible government. Government ministers could be, but were not required to be, members of Parliament. The way was left open for the development of a system closer to that existing in the United States of America, where the President (who heads the government) and his Ministers (appointed by the President with the approval of the Senate) are not members of Congress, and the President governs for a fixed term of four years irrespective of whether the party he or she belongs to possesses a majority of seats in either or both Houses of Congress. Secondly, the Senate was prohibited from amending bills appropriating money for the ordinary annual services of government and bills imposing taxation but could amend other types of appropriation bills. However, it would be able to request amendments to bills it could not amend (see section 53 of the Constitution). This arrangement became known as the ‘compromise of 1891’.

By 1897, however, there was a general consensus among delegates that ministers ought to be members of parliament (see section 64 of the Constitution). This left the issue of whether the Senate should have the power to amend money bills. The smaller colonies were adamant that it should. The larger states were equally adamant that it should not. The impasse was resolved only when six delegates out of a total of fifty, realising that federation itself was at stake, changed their votes and restored the ‘compromise of 1891’. In their seminal work, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth (1901), John Quick and Robert Garran described this debate as the ‘most momentous in the Convention’s whole history’ (p. 172).