Stillbirth in Australia—an

overview

2.1

Australia is one of the safest places in the world to give birth, yet six

babies are stillborn here every day, making it the most common form of child

mortality in Australia.

2.2

Stillbirth affects over 2000 Australian families each year. For every

137 women who reach 20 weeks' pregnancy, one will experience a stillbirth. For

women from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds the rate is double

that of other Australian women.[1]

2.3

Furthermore, the rate of stillbirth in Australia has not changed over

the past two decades, despite modern advances in medical practice and health

care. According to the Centre of Research Excellence in Stillbirth (Stillbirth

CRE), '[u]p to half of stillbirths at term in Australia are unexplained'.[2]

2.4

Stillbirth is one of the most devastating and profound events that any

parent is ever likely to experience. It is 30 times more common than Sudden

Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), but stillbirth receives far less public or

government attention than other infant and childhood deaths.[3]

2.5

Stillbirth is a hidden tragedy. The culture of silence around stillbirth

means that parents and families who experience it are less likely to be prepared

to deal with the personal, social and financial consequences. This failure to

regard stillbirth as a public health issue also has significant consequences

for the level of funding available for research and education, and for public

awareness of the social and economic costs to the community as a whole.

The sorrow and sadness associated with a stillbirth has a

profound rippling effect across communities that is long-lasting and is

acknowledged to have significant social, emotional and economic impacts.[4]

2.6

This chapter outlines the numbers, rates, causes, and risk factors of

stillbirth in Australia compared with other high-income countries.

Stillbirth rates

International trends

2.7

Internationally, the number of stillbirths occurring at or after 28

weeks' gestation declined by 19.4 per cent between 2000 and 2015, representing

an annual reduction of two per cent. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated

that, in 2015, there were 2.6 million stillbirths at or after 28 weeks'

gestation worldwide. Most (98 per cent) stillbirths occur in low- and

middle-income countries, and over half (60 per cent) occur in rural areas.[5]

2.8

The table below shows the rates and ranking of selected countries,

including Australia, in 2009 and 2015, based on the WHO definition of

stillbirth.

Table 2.1: Stillbirth rate (at or

after 28 weeks' gestation) per 1000 births, and rank, by country, 2009 and 2015[6]

| Country |

2009 |

2015 |

| Rate |

Rank |

Rate |

Rank |

| Finland |

2.0 |

1 |

1.8 |

4 |

| New Zealand |

3.5 |

34 |

2.3 |

11 |

| Australia |

2.9 |

15 |

2.7 |

17 |

| UK & Northern Ireland |

3.5 |

33 |

2.9 |

26 |

| USA |

3.0 |

17 |

3.0 |

29 |

| Canada |

3.3 |

26 |

3.1 |

30 |

| Malaysia |

5.9 |

55 |

5.8 |

55 |

| China |

9.8 |

82 |

7.2 |

68 |

| India |

22.1 |

154 |

23.0 |

165 |

| Pakistan |

46.7 |

193 |

43.1 |

194 |

High-income countries

2.9

Significant movement up the rankings occurred between 2009 and 2015 for

the United Kingdom (UK) and Northern Ireland, and New Zealand; Australia

slipped by two places; and the United States of America (USA), while having the

same rate of stillbirth in both years, fell in ranking from 17 to 29.

2.10

Analyses of data in high-income countries show a decrease in the rate of

stillbirth over the past 50 years, attributed largely to improvements in

intrapartum care, but there has been little or no improvement over the past two

decades and evidence of increases in some countries including Australia.[7]

2.11

In 2017 countries with the lowest stillbirth rates were Iceland (1.3

stillbirths per 1000), Denmark (1.7), and Finland (1.8).[8]

2.12

Australia (2.7 stillbirths per 1000) lags well behind other high-income

countries, with the stillbirth rate beyond 28 weeks of pregnancy 35 per cent

higher than the best-performing countries.[9]

Australian trends

2.13

The rate of stillbirth in Australia is based on the Australian Institute

of Health and Welfare (AIHW) definition of stillbirth as a fetal death

occurring at 20 or more completed weeks of gestation or 400 grams or more

birthweight.[10]

2.14

The AIHW uses this definition for the National Perinatal Data Collection

(NPDC). This differs from the definition recommended by the World Health

Organisation (a baby born with no signs of life at or after 28 weeks of

gestation or 1000 gram birthweight) and the United Kingdom (24 weeks).[11]

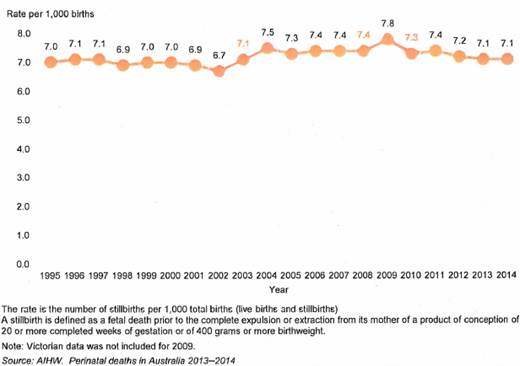

2.15

Between 1995 and 2014, there was an overall reduction in neonatal deaths

(deaths occurring from birth to 28 days old), from 3.2 to 2.6 per 1000 births.

However, the rate of stillbirth remained relatively unchanged, varying between

6.7 and 7.8 deaths per 1000 births over the same period (see Figure 2.1 below).

Figure 2.1: Stillbirth rate in

Australia, 1995−2014[12]

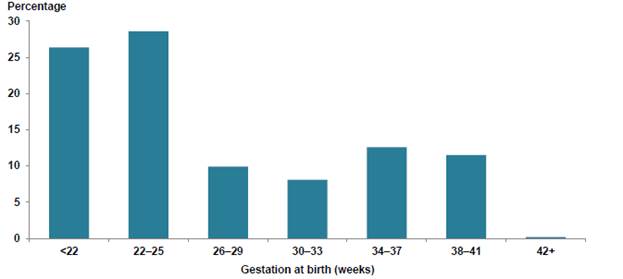

2.16

Figure 2.2 shows the percentage of stillbirths by gestation at birth in

Australia over 2013 and 2014.

Figure 2.2: Percentage of

stillbirths by gestation at birth in Australia, 2013−14[13]

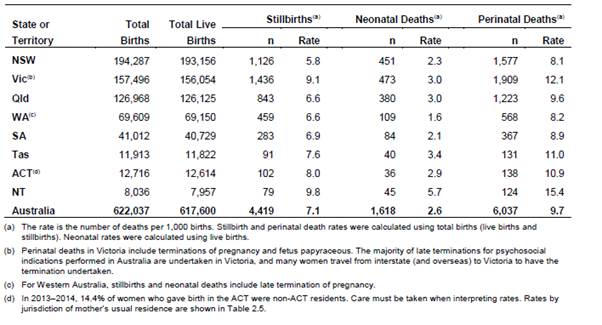

2.17

Table 2.2 presents the numbers of births, live births and stillbirths

and the rate of stillbirths by jurisdiction between 2013 and 2014.

Table 2.2: Perinatal deaths by

jurisdiction in Australia, 2013−14[14]

Causes of stillbirth

2.18

A high proportion of stillbirths in Australia are unexplained. Many occur

unexpectedly in late pregnancy, and many are related to undetected fetal growth

restriction (FGR) and placental conditions.

Many of the predisposing factors for stillbirth are closely

linked and overlap with those responsible for other serious perinatal outcomes

including hypoxic [lack of oxygen to the brain] and traumatic injury to unborn

babies.[15]

2.19

An AIHW study of the causes of stillbirths occurring between 1991 and

2009 showed the major causes of stillbirth in Australia as follows:

Table 2.3: Major causes of

stillbirth in Australia, 1991−2009[16]

| Cause of stillbirth |

% |

Number |

| Congenital abnormality |

22.3 |

1891 |

| Unexplained antepartum death |

22.3 |

1896 |

| Maternal Conditions |

13.4 |

1141 |

| Spontaneous pre-term (<

37 weeks gestation) |

11.5 |

980 |

| Specific perinatal condition |

8.1 |

684 |

| Fetal growth restriction (FGR) |

7 |

593 |

| Antepartum haemorrhage |

6.9 |

589 |

| Perinatal infection |

3.5 |

251 |

| Hypertension |

3.1 |

265 |

| Hypoxic peripartum death |

1.9 |

159 |

| No obstetric antecedent |

0.5 |

41 |

| Total |

100 |

8490 |

2.20

AIHW data for 2013−14

showed the main causes of stillbirth as congenital anomaly (27 per cent),

unexplained antepartum death (20 per cent) and maternal conditions (11 per

cent).[17]

Risk factors

High-income countries

2.21

According to recent international research, 90 per cent of stillbirths

in high income countries occur in the antepartum period, and are frequently

associated with placental dysfunction and FGR. Many stillbirths remain

unexplained, while others are associated with preventable lifestyle factors.[18]

2.22

One international study of stillbirth summed up the situation in

high-income countries:

The proportion of unexplained stillbirths is high and can be

addressed through improvements in data collection, investigation, and

classification, and with a better understanding of causal pathways. Substandard

care contributes to 20–30% of all stillbirths and the contribution is even

higher for late gestation intrapartum stillbirths. National perinatal mortality

audit programmes need to be implemented in all high-income countries. The need

to reduce stigma and fatalism related to stillbirth and to improve bereavement

care are also clear, persisting priorities for action. In high-income

countries, a woman living under adverse socioeconomic circumstances has twice

the risk of having a stillborn child when compared to her more advantaged

counterparts. Programmes at community and country level need to improve health

in disadvantaged families to address these inequities.[19]

2.23

Potentially modifiable risk factors for stillbirth in high income

countries include maternal overweight and obesity, advanced maternal age,

placental abruption and pre-existing hypertension and diabetes.[20]

Australia

2.24

Similarly, the major risk factors for stillbirth in Australia have been

identified by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) as obesity, advanced maternal age, smoking, first

pregnancy and diabetes and hypertension.[21]

2.25

As in other high-income countries, there is also an elevated risk of

stillbirth and other adverse pregnancy outcomes for women and women who live

with social disadvantage.[22]

2.26

In 2011−12,

the stillbirth rate for babies of teenage mothers and mothers older than 45 was

more than twice that for mothers aged 30−34

(13.9 and 17.1 versus 6.4 deaths per 1000 births).[23]

2.27

In 2015, most stillborn babies were preterm (85 per cent) and the mean

birthweight of stillborn babies (1125 grams) was far lower than for live-born

babies (3342 grams). Four in five stillborn babies were low birthweight, and

more than half (65 per cent) were extremely low birthweight (<1000 grams).[24]

2.28

A study of stillbirths in New South Wales found additional risk factors,

including small birthweight for gestation, low socioeconomic status, previous

stillbirth or preterm birth, Aboriginality, and maternal country of birth.[25]

2.29

However, studies have found that risk factors differ across gestational

age and reflect different causes, with foetal anomalies and infection

associated with stillbirth at early gestation; anomalies and antepartum

haemorrhage across 26−33

weeks; vasa praevia,[26]

infection and diabetes affecting late term stillbirths; and FGR being a strong

predictor across all gestations.[27]

2.30

Professor Craig Pennell, Senior Researcher at the Hunter Medical

Research Institute, remarked that about half of the causes of stillbirth have a

primary placental origin, but identifying those women whose placentas are not

functioning well becomes increasingly difficult as a pregnancy progresses:

...we're relatively good at picking up the low-hanging fruit

when it comes to pregnancies, but we're not very good at determining when a

pregnancy that is going well starts to fall off. The simplest way to explain

that is that the average placenta has about a 30 per cent reserve. So if I'm

looking at a patient and her baby's growing normally and her blood flow studies

are normal, all that tells me is that her placenta is functioning between 67

per cent and 100 per cent. It doesn't tell me where it is in that range.[28]

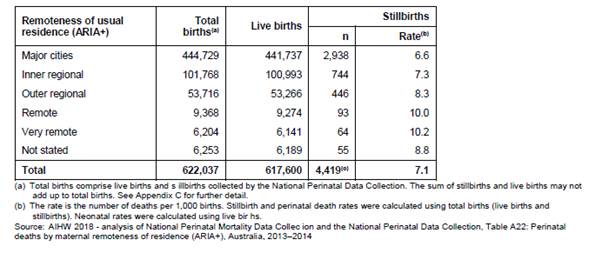

Regional and remote communities

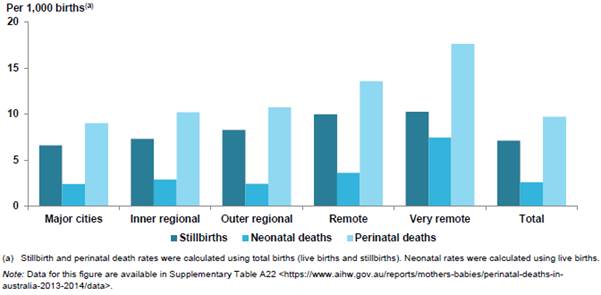

2.31

Around 33 per cent of all stillbirths in Australia are to women who live

in regional and remote areas of Australia. According to AIHW data, the further

away women are from a major city, the higher the rate of stillbirth, as shown

in Table 2.4 below.

Table 2.4: Stillbirth deaths by

maternal remoteness of residence, Australia, 2013−14[29]

2.32

The AIHW found that babies born to mothers living in remote and very

remote areas were 65 per cent more likely to die during the perinatal period

than babies born to mothers living in major cities or inner regional areas, as

shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: Perinatal mortality

rates by remoteness of maternal residence in Australia, 2013−14[30]

2.33

This trend may increase in the future as a result of the closure of

small maternity units in rural and remote communities across Australia, where pregnant

women are less likely to leave their community to seek antenatal care until

late in their pregnancy.[31]

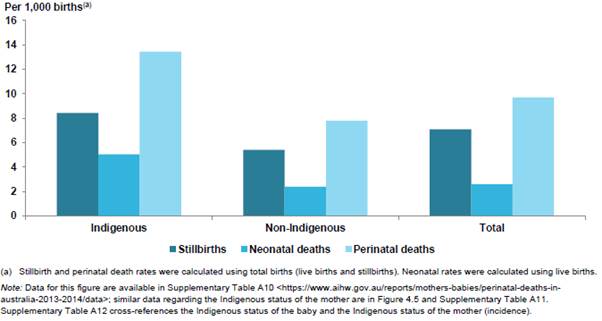

Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander communities

2.34

The rate of stillbirth for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies

is double that of other Australian women (13 in 1000 births compared to six in

1000 births).[32]

2.35

Whilst there has been some progress in reducing the disparity for

Indigenous women, this varies across jurisdictions. In Queensland, for example,

rates are reducing, in Western Australia there has been no improvement, and in

Victoria the rate amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women has

fallen to that of non-Indigenous women.[33]

2.36

A recent study of stillbirth rates in Queensland found that Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander women continued to be at increased risk of

stillbirth as a result of potentially preventable factors including maternal

conditions, perinatal infection, FGR and unexplained antepartum fetal death.[34]

2.37

Figure 2.4 shows the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stillbirth

rate by Indigenous status of the baby in Australia for the period 2013−14.

Figure 2.4: Perinatal mortality

rates by Indigenous status of the baby in Australia, 2013−14[35]

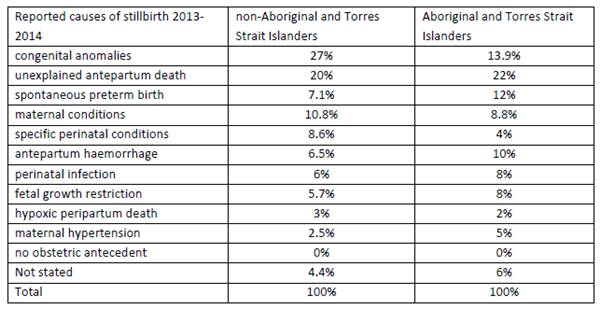

2.38

Table 2.5 compares the reported causes of stillbirth in 2013−14 between non-Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander women and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

women.

Table 2.5: Perinatal Society of

Australia and New Zealand Perinatal Death Classification (PSANZ-PDC) cause of

stillbirth comparing non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, 2013−14[36]

2.39

Obesity is a major maternal risk factor for stillbirth in high income

countries. The rate of obesity increases with remoteness, with rural and remote

people 30 per cent more likely to be obese than those in major cities.

2.40

Maternal smoking is another risk factor for stillbirth in high income

countries. In Australia, 45 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander

mothers smoke during pregnancy and are more likely to have pre-existing

diabetes or hypertension.[37]

2.41

There has been a significantly increased risk of stillbirth due to an

outbreak of syphilis infection among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

women living in regional and rural areas.[38]

The Australian government responded in 2018 by introducing rapid point-of-care

testing across three high-risk regions in northern Australia, including a

strong focus on expectant mothers and women considering pregnancy.[39]

2.42

Such outbreaks have highlighted the need for infection prevention and

control through improved antenatal screening, treatment and notification of

partners as part of a broader stillbirth prevention strategy.[40]

Culturally and linguistically

diverse communities

2.43

There are higher stillbirth rates amongst culturally and linguistically

diverse (CALD) communities in Australia. In 2013−14,

1531 (34.6 per cent) of the 4419 stillbirths that occurred in Australia were

born to women who were themselves born in countries other than Australia.[41]

2.44

The percentage of women from CALD backgrounds in Victoria is slightly

higher, with 38.5 per cent of women giving birth in 2016 born outside of

Australia. However, information on ethnicity is not routinely collected for

perinatal data collections, and has resulted in incomplete data.[42]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page