Key issues

2.1

The National Quality Framework (NQF) aims to ensure the provision of high

quality early childhood education and care (ECEC) services. Most submitters

and witnesses to the childcare inquiry therefore supported the NQF's regulation

of the ECEC sector.[1]

2.2

However, the committee heard that there is still a wide variety and

amount of regulation affecting the ECEC sector.[2]

The Australian Childcare Alliance (NSW) warned that 'regulatory requirements

usually come at a cost' and can become 'burdensome, excessive and/or arguably

counter-productive'.[3]

The Centre for Independent Studies (CIS) similarly submitted that regulation

can comprise red tape if it is ineffective or inefficient:

Even where a policy objective is recognised as important (for

example, early childhood development), some or all of the regulations

implementing the policy may be red tape if they are ineffective or an

inefficient way to achieve the desired objective.[4]

2.3

This chapter discusses the following matters raised during the inquiry:

-

NQF and regulatory reduction;

-

the Family Day Care (FDC) sector;

-

staffing regulations;

-

regulatory compliance costs; and

-

fee assistance and the Child Care Subsidy.

NQF and regulatory reduction

2.4

The Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) submitted

that the NQF has improved ECEC regulation through the creation of a nationally

unified system. This system replaced eight state and territory regulatory models

plus a partially overlapping national quality assurance regulatory scheme administered

at the Commonwealth level:

Prior to the NQF, requirements...were often duplicated...Expectations

were inconsistent...with varying standards for service types, ratio and

qualification requirements. Information flows between the nine regulators were

highly restricted...A provider operating across multiple jurisdictions and

regulators could find themselves needing to comply with multiple but slightly

varying paperwork, notification and record keeping obligations both within a

single jurisdiction...or between jurisdictions.[5]

2.5

Both ACECQA and the Department of Education and Training (Department)

argued that ongoing review ensures the NQF delivers 'quality outcomes for

children, while balancing the need to reduce red tape and unnecessary

administrative burden for approved providers and educators'.[6]

2.6

Not all submitters agreed that the NQF has improved national consistency

or reduced regulatory burden,[7]

with some expressing concern about increasing amounts and costs of regulation.

The CIS, for example, submitted:

The childcare sector in Australia has been characterised by

growing government intervention in recent decades, culminating in the

introduction of the National Quality Framework (NQF). Inevitably, this has

precipitated new forms of red tape for the sector. Many of the NQF regulations

entail significant administrative and compliance costs, while many of the cited

benefits are contestable and not based on compelling evidence.[8]

2.7

Family Day Care Australia (FDCA), for example, argued that its

sector has been adversely affected, resulting in 'excessive administrative

burden, service closures and a decrease in high level quality ratings'.[9]

Australian Childcare Alliance referred to certain 'onerous' reporting

requirements and stated:

...the government must

acknowledge the increase of paperwork and stress that has been introduced to

the sector over the past 10 years. It is disappointing when our governing body

minimises this by stating that paperwork has reduced.[10]

Family Day Care sector

2.8

Several witnesses supported a flexible childcare market that provides

children with the formal or informal care that best suits their family

circumstances.[11]

For example, Andrew Paterson, Chief Executive Officer of FDCA, advised that

FDC is an option of choice for many Australian families (currently, about 185

000 children; 14.5 per cent of children in formal care). He explained that FDC

provides:

...quality flexible early childhood education and care in small

groups, in a natural home learning environment. The sector is unique in its

capacity to service the diverse and disparate needs of children, families and

communities. Family day care is the only approved service type that can

effectively and efficiently deliver non-standard-hours care, including weekends

and overnight, and is heavily represented among regional, rural and remote

communities and amongst some of the most socio-economically disadvantaged

segments of Australian society.[12]

2.9

Mr Paterson detailed how the FDC sector has been challenged by a

significant increase in regulation, coupled with a decline in operational

funding. This funding previously supported FDC services in providing FDC

educators (who are largely small business operators) with regulatory support.

Mr Paterson indicated that the sector has been struggling with regulatory

compliance with consequent effects on many small businesses:

...since making our submission, we have seen quality services

who have battled to remain viable and, confused by the constantly changing

regulatory landscape, being disproportionately sanctioned for administrative

noncompliance and forced out of the sector for administrative error rates of

less than one per cent over two years.[13]

2.10

In its submission, FDCA mentioned two particular concerns: coordinator‑to‑educator

ratios (1:25) and caps on the number of educators registered with an approved

service. These caps were introduced as part of the 2017–2018 changes to the NQF

and are determined by the regulatory authority in each jurisdiction:

[These are] an example of excessive regulatory restriction of

market competition which ultimately will universally limit the number of

educators within family day care services across Australia and affect the

choices available to Australian families...educator caps unfairly limit family

day care educators' ability to choose a service to register with and has the

potential to severely limit the viability of the family day care sector. Family

day care services are businesses like any others and legitimate expansion needs

to be an option to remain viable in a competitive, demand driven and dynamic

market.[14]

2.11

In relation to these concerns, Gabrielle Sinclair, Chief Executive

Officer of ACECQA, advised that the Council of Australian Governments (COAG)

Education Council will shortly report to COAG on ways to better support FDC

educators. Conceding that these educators are isolated, Ms Sinclair said:

I'm quite anxious to see this report and to see whether there

could be something else that we haven't thought of that would help them. Maybe

it means that we have to put some more in to their professional learning and

support, or maybe it's something that could be a little bit simpler and

less expensive. At this stage, I know that many family day care providers have

decided to close up shop because they say that families choose to go to long

day care.[15]

Department response

2.12

Asked for its response, the Department's representative commented on the

amount of work recently conducted to address sharp practices in the FDC sector

(such as the claiming of benefits for non-existent enrolments). The officer

said that 'the government is very committed to the family day care sector', the

majority of suppliers being 'honest, hardworking people providing excellent

service to families'.[16]

2.13

The officer agreed that the FDC sector could be more price competitive

than long day care (LDC) but cautioned that this was not yet certain:

The numbers, largely because of the problems we've had recently,

haven't borne that out. In fact...the average cost per hour for family day care

was similar to and sometimes higher than long day care... It is cheaper now but

not a great deal. The last data we had has long day care averaging about $9.20

an hour and family day care at $8.80...Family day care, at the bottom end of a

quite skewed bell curve, is quite a bit cheaper generally than long day care.

It's because of the overheads being cheaper. Why are people leaving it? There

are various reasons. They may or may not be viable.[17]

Committee view

2.14

The committee supports the availability of flexible childcare options

for Australian families and is concerned by claims that the viability of small

businesses in the FDC sector is under threat. Ultimately, this impacts both the

availability and affordability of child care and is contrary to families' needs

and Australian Government policy. The committee suggests that the

Australian Government should demonstrate its commitment to the FDC sector by

working toward red tape reductions as part of COAG's

current review process.

2.15

The committee cannot see why FDC is not offering substantially lower

cost childcare options to benefit a wide range of families which struggle to

fund LDC. Its conclusion is that bureaucracy and red tape are seriously

increasing the cost of FDC and impeding the viability of the sector.

Recommendation 1

2.16

The committee recommends the Australian Government, through the Council

of Australian Governments, expeditiously work toward reducing the regulatory

burden in the Family Day Care sector, including by removing limits on the number

of educators in each service.

Staffing regulations

2.17

More broadly, submitters and witnesses commented at length on two

particular staffing regulations—ratios and qualifications—which are mandated by

the NQF and which vary across jurisdictions. The CIS submitted that these regulations

are burdensome as labour-related costs account for over 60 per cent of approved

providers' total operating expenses. For example, with educator-to-child ratios,

'centres have to employ more staff and,

obviously, that leads to increased wage costs which are passed onto parents'.[18]

Its submission cautioned:

In the absence of any efforts to lighten the burden of regulations,

labour and regulatory costs can be expected to continue rising over time. This

will flow through to higher childcare fees and, consequently, the more generous

Child Care Subsidy, coming into effect from 2 July 2018, will be less effectual

than desired in improving childcare affordability.[19]

Ratio requirements

2.18

Some information presented to the childcare inquiry questioned the

rationale for ratios in the ECEC sector. Chiang Lim, Chief Executive Officer of

Australian Childcare Alliance (NSW), and FDCA noted that, prior to

implementation of the NQF, there was variation between jurisdictions.[20]

2.19

In addition, some submitters and witnesses queried the evidence-base for

the current ratios (educator-to-child; coordinator-to-educator; et cetera).[21]

Dr Buckingham said that ratios are sensible for very young children but

less so for older children whose care needs are fewer.[22]

FDCA commented that 'there is no evidence that indicating a specific ratio of coordinators

to educators will promote the best outcomes for children'.[23]

2.20

Australian Childcare Alliance indicated that, in at least one

jurisdiction, there has been inadequate cost/benefit analysis of ECEC

regulation:

[Introduction of the 1:5 ratio for two to three years old

children] resulted in many services charging higher fees for this age

group...Minimal NSW‑centric analysis appears to have been undertaken at the

time to investigate how these costs would be covered by childcare services

and/or how such costs would be passed on as increased fees to parents. The resulting

reduction in the availability of affordable childcare places in the under 3 age

group also does not appear to have been considered.[24]

2.21

Ms Sinclair from ACECQA said that the current ratio requirements are

based on world's best practice—such as identified in the E4Kids study

conducted by the Melbourne Graduate School of Education at the University of

Melbourne.[25]

However, the committee notes that when the Productivity Commission examined

educator‑to‑child ratios it reported:

The key policy challenge regarding these ratios and

qualifications is that it is impossible to tell whether they have been set at

appropriate levels. This is because there is limited evidence to support

specific settings for these requirements or to reliably quantify their benefits.[26]

Qualification requirements

2.22

Some submitters and witnesses raised the issue of qualification

requirements. The NQF sets out minimum qualifications for persons working in

centre-based and FDC services, as well as school-aged children in out of school

hours care services.[27]

For example, in a centre-based service half the educators required to meet the

educator-to-child ratio must have, or be working toward, a diploma level

qualification. All other educators must have, or be working toward, a relevant

Certificate III qualification.[28]

2.23

The CIS, for example, contended that the costs of this regulation

outweigh its benefits, with Dr Buckingham stating that there is no evidence of

higher qualifications improving outcomes for children. She explained:

There are some social and behavioural impacts, at least in

the short term, but very little evidence of any cognitive benefits in terms of

vocabulary, literacy and numeracy skills—those sorts of things. Any tiny

impacts that are found are generally not found to be durable so when [they are]

followed up three or four years later those effects have washed out.[29]

2.24

In contrast, Dr Cannen from United Voice argued that strong evidence 'directly

links qualifications of educators and teachers to higher NAPLAN scores in year

3 and better performance at age 15'. Dr Cannen referred to research conducted

by Dr Dianna Warren and others in relation to:

...how the number of words that children hear has a direct

impact on them cognitively, emotionally and socially. This is the 'iron triangle'

for higher quality early education, which is to do with ratios, qualifications

and group sizes. That formula is based on years of international research,

including OECD reports—several Starting strong reports—which indicate

things like our National Quality Framework is integral to providing the best

education and care for our children.[30]

2.25

Ms Samantha Page, Chief Executive Officer of Early Childhood Australia

(ECA), agreed that, for children in formal care:

...it's really important that the staff that work in that

setting have early childhood qualifications. That is well documented in

research... Qualifications make a difference, ratios make a difference, group

size makes a difference, and the quality of the setting and the environment

that is available to the children makes a difference, and that's why we have

national quality standards.[31]

2.26

ACECQA's representative, Ms Sinclair, acknowledged that qualifications

are not the only criterion: 'what we want in the ideal world is people who love

children, are experienced and also have the qualification'.[32]

In relation to the evidence-base, she said:

...the international evidence looks at the quality from the

perspective of the iron triangle—that is, qualifications of staff,

child-to-educator ratio and group size...those three things don't change...[Further]

the research over the last 50 to 60 years has shown that class size and

educator-to-child ratios are very significant for young children and children

with disability.[33]

2.27

The committee further notes the following comment from the Productivity

Commission:

The evidence that specific levels of qualifications improve

the learning and development outcomes for children under 3 years of age is

absent and evidence of positive impacts of qualifications, by themselves, is

inconclusive.[34]

Committee view

2.28

The committee notes the variation in staffing regulations as permitted

under the National Quality Framework. The committee acknowledges that there is

a rationale for imposing staffing ratios but is not convinced that the current

policy settings are correct. The committee notes that there is insufficient

evidence in this area, as highlighted by the Productivity Commission in its

2014 report Childcare and Early Childhood Learning.

2.29

The committee recognises that there are various views about the value of

staffing qualifications in ECEC, particularly across different age groups. In

relation to the youngest cohorts of children, the committee heard that while there

is some international evidence to support the current regulation, the committee

is mindful that not so long ago (2014) the Productivity Commission was critical

of the evidence-base for these cohorts. The committee suggests that it would be

prudent to establish a sound evidence-base to promote the relationship between

staffing qualifications and children's outcomes, and to avoid the perception of

that regulation being unnecessary red tape.

2.30

The committee further notes that an alternative to formal child care is

for children to remain at home with their parents who usually have no formal qualifications

in early childhood education. Arguments in support of higher qualifications for

childcare workers, if they result in fewer children receiving early childhood

education due to resulting costs, cannot be supported.

Recommendation 2

2.31

The committee recommends that the Australian Government, through the

Council of Australian Governments, promote and/or develop an evidence‑base

for staffing ratios and staffing qualifications in early childhood education

and care, as a quality component of the National Quality Framework.

Recommendation 3

2.32

The committee recommends that, following

establishment of the evidence‑base for staffing ratios and staffing

qualifications in early childhood education and care, the principles of the

National Quality Framework be reviewed to ensure they appropriately reflect the

evidence-base.

Recommendation 4

2.33

The committee recommends that, in reviewing the principles of the

National Quality Framework, Australian, state and territory governments

recognise that formal qualifications are not the only prerequisite for the

provision of high quality child care, as this can also be provided by parents.

Regulatory compliance costs

2.34

Since 2013, there have been a number of inquiries or surveys about

regulation in the ECEC sector. ACECQA, for example, measures approved

providers' perceptions of administrative burden, which it and ELACCA argued

enable identification of and reduction in burdensome regulation.[35]

2.35

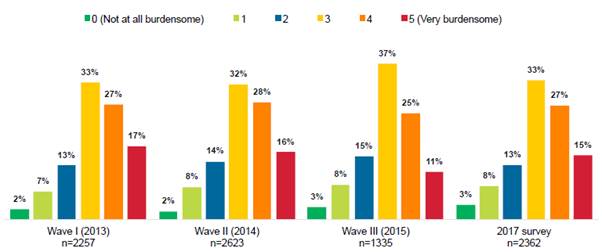

In its latest performance report, ACECQA highlighted strong support for

the NQF (97 per cent), as well as a high perception of regulatory burden

(Figure 2.1).[36]

Figure 2.1:

Perception of overall burden, 2013–2017

Source: ACECQA, National

Partnership Annual Performance Report, National Quality Agenda, December 2017,

p. 73.

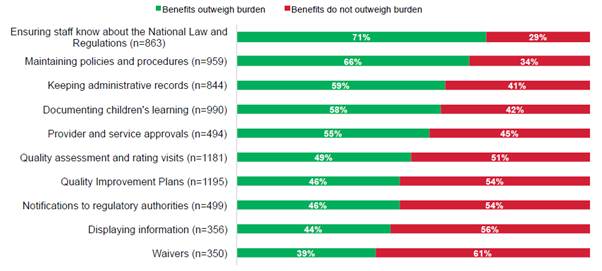

2.36

According to ACECQA, approved providers identified six administrative

areas as creating the most regulatory burden,[37]

five of which were considered more beneficial than burdensome (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Provider

perceptions, administrative burden, specific requirements

Source: ACECQA,

National Partnership Annual Performance Report, National Quality Agenda,

December 2017, p. 75.

2.37

Some submitters and witnesses considered that the benefits of quality

ECEC outweigh the regulatory burden.[38]

ACCS and Michael Tizard, Chief Executive Officer of The Creche and Kindergarten

Association (C&K) observed also that perceptions of administrative burden

have declined over time.[39]

2.38

However, Australian Childcare Alliance (NSW) submitted that its own Annual

Early Learning and Childcare Services Survey reveals ongoing concerns about

significant regulatory burden, including:

-

a high percentage of staff (62 per cent) spending more than one-third

of their time on administrative tasks;

-

more than half of staff (58.9 per cent) considering that NSW staffing

ratios had negatively impacted the cost of running a service;

-

more than half of staff (51.23 per cent) considering that time

spent on administrative tasks was negatively impacting costs to services; and

-

a high percentage of staff (61.52 per cent) believing that the

NQF was increasing paperwork.[40]

Committee view

2.39

The committee notes current surveys indicating that approved providers

perceive a high level of regulatory burden, notwithstanding their support for

the objectives of the NQF. The committee believes this must translate to a

considerable amount of time and money being spent on compliance. The Department

has not recently reported any significant regulatory savings in ECEC, although

current reforms are expected to deliver over $100 million in savings. The

committee believes that these savings should be reported in the Department's

next annual report for the Deregulation Agenda.

Recommendation 5

2.40

The committee recommends that the Department of Education and Training

provide a detailed annual report to the Department of Jobs and Small Business,

to provide greater transparency about red tape reductions in early childhood

education and care.

Fee assistance and the Child Care Subsidy

2.41

The CIS argued that the Australian Government, which provided 81.6 per

cent of total government ECEC expenditure in 2016–2017,[41]

should be strongly motivated to minimise unnecessary and/or ineffective

regulation, as these contribute to the rising cost of child care.[42]

2.42

According to Australian Childcare Alliance, there is too much regulation

which affects childcare affordability: 'regulatory requirements come at a cost

that [is] inevitably passed onto families reducing affordability'.[43]

CIS added that these amounts also contribute to the increasing cost of

Australian Government fee assistance,[44]

which in 2016–2017 amounted to $7.7 billion.[45]

Fee assistance policy objectives

2.43

Australian Government fee assistance is based on two policy objectives—namely,

workforce participation and quality ECEC.[46]

Ms Page from ECA commented on a third objective—the reduction of inequity and

vulnerability—which she argued was the primary basis for ECEC regulation:

Children who are coming from a disadvantaged background will

benefit the most from quality early childhood education and care...It's not

necessarily that parents are choosing between staying at home and providing a

safe, rich learning environment for children or going to work and those children

going to a safe, rich learning environment somewhere else. There are a host of

other circumstances that children can be left in that are very undesirable and

very unsafe, and that's why we provide a regulated system of education and care

in this country.[47]

2.44

Dr Emma Cannen, Policy and Stakeholder Manager, Big Steps, United Voice,

argued that fee assistance produces multiple economic benefits:

There are different ways that you can contribute to the

economy. There is firm evidence that maternal workforce participation in this

country is very low compared to other OECD countries, and it does increase

returns on the economy...But there are broader returns on investment to the

economy, regardless of the question of maternal participation, because of the productivity

and children's outcomes. When you have children that are performing better on

NAPLAN and PISA tests, they go on to have better jobs and have continuous input

into the economy. There is also less strain on the taxpayer in relation to

health, training, education and even the criminal justice system.[48]

2.45

Other submitters and witnesses—such as Australian Community Children's

Services (ACCS) and Community Child Care Association (CCCA)—agreed that ECEC

benefits are experienced across a life cycle.[49]

Their submissions referred to economic modelling conducted by Price Waterhouse

Coopers (2014), whose key findings about returns on investment were reiterated

by Ms Page from ECA:

By investing more in early childhood education and care and

increasing children's participation in early childhood education and care the

Australian economy stands to benefit by $6 billion from increased workforce

participation, particularly amongst women. We stand to benefit by another $10.3

billion from improving children's transition to school—making sure that

children are ready for learning, that they're inquisitive, confident learners

and that they are ready to make that important transition. But the biggest gain

was an estimated $13 billion that we stand to gain from addressing vulnerability

amongst children who may not have had the best start in their early years and

can improve through accessing a quality early childhood program.[50]

2.46

Ms Page argued there are social and economic benefits for women in high‑income

families returning to the workforce:

Where we invest a small amount generally to encourage

high-income families to access the universal system of early childhood

education and care we get well and truly more money back than we invest,

through the taxes paid through increased workforce participation...[Also, staying

at home] has significant impact down the track on women's superannuation

savings, on women's capacity to earn later in life and on separated families,

where there is then an inequity between one parent, who's been out of the

workforce for a significant period of time, and the other parent, who hasn't.[51]

2.47

Elizabeth Death from the Early Learning and Care Council of Australia (ELACCA)

and Dr Cannen from United Voice concurred that fee assistance is a factor in

high-income families' decision to return to work.[52]

Linda Davison, Chairperson of CCCA, added:

I run a service and I know that there are families who are

currently using our service who are thinking very carefully about whether one

or other of the parents will return to work, and in what capacity, very much on

the basis of the fact that they will no longer receive any childcare subsidy at

all. Some of these women—they are mostly women—are highly skilled women in very

senior positions. Yes, they are high-income earning families, but they're also

families who have high expenses.[53]

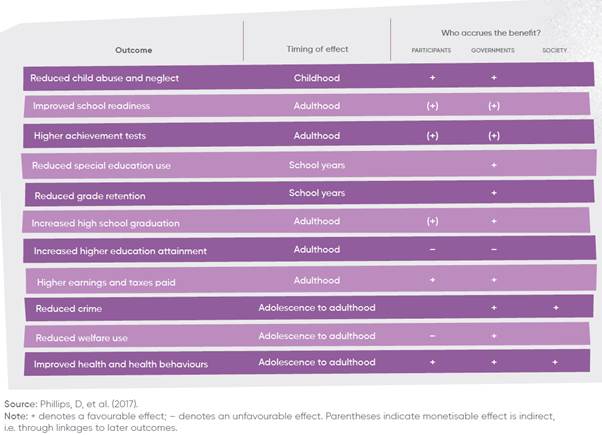

2.48

The committee notes the following findings of the Lifting Our Game,

Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools

Through Early Childhood Interventions report (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3: Economic

effects of quality early childhood education

Source: Pascoe, M.

and D. Brennan, Lifting Our Game, Report of the Review to Achieve Educational

Excellence in Australian Schools Through Early Childhood Interventions,

December 2017, p. 55.

Increased regulation

2.49

Submitters and witnesses commented that the new funding arrangements

have markedly increased the administrative burden for approved providers and

families.[54]

ELACCA commented, for example:

The implementation of this [reform] requires major system

reform for Government, providers and families prior to and post 2 July 2018 and

involves lengthy, complex and costly change management...the Office of Best

Practice Regulations (OBPR) noted on review of the RIS that there will be significant

impacts on the early childhood education and care market and recommended a more

in-depth analysis of the expected net benefits.[55]

2.50

Mr Tizard described how implementation of the Child Care Subsidy has impacted

families and services in the C&K community:

It's having an enormous impact, in terms of readiness.

There's a new time and attendance system—we're installing an electronic

check-in system so that we can record time of arrival and time of departure.

There's enormous work to vary our enrolment forms so that they meet the

compliant written agreement requirements. We are educating our educators about

the many aspects of the new system. We are working with our families, in terms

of getting them ready and getting them onto myGov. There's been advertising,

but a lot of families rely on directors.[56]

2.51

Mr Tizard explained that the changes will also affect affordability and

accessibility, and potentially affect the diversity of current ECEC services:

We are having a look at what impact it's going to have on the

utilisation of our services. We're concerned about services in disadvantaged

areas where eligibility may drop if they don't meet the activity test. We're

concerned about the large number of kindergartens and the fact that families

may exit kindergarten to go into long day care because it is cheaper. There are

many tentacles to this new package for an organisation like C&K.[57]

Affordability and accessibility

2.52

There are three factors that determine a family's level of Child Care

Subsidy (combined family income, activity test and service type). Alys Gagnon,

Executive Director of The Parenthood, expressed concern that not all families

will benefit from Child Care Subsidy due to the new means test. Ms Gagnon said

that test might even provide less assistance to children from vulnerable and

disadvantaged backgrounds:

Some families will be demonstrably worse off, around a

quarter of a million families across all income brackets...this will mean they

absorb the financial hit. A parent, probably the mother, will stop working or

will cut their hours at work or they will withdraw their child from early

learning... it is the children who derive the greatest benefits from early

learning—those from disadvantaged backgrounds—who are most likely to be

withdrawn.[58]

2.53

Other witnesses expressed concern about families' readiness for Child

Care Subsidy due to the administrative requirements for the transition.[59]

Ms Death of ELACCA said:

We've got families who don't necessarily always have access

to the internet—they need to have a myGov account—and they have a whole range

of other issues there that provide hurdles, and often it's the most vulnerable

families who can't jump those hurdles faster.[60]

2.54

The committee notes that, as at 2 July 2018, more than one million

families had transitioned to the Child Care Subsidy and that there will be a

three month grace period for approximately 51 000 families who experienced

difficulties transitioning by that date.[61]

Attendance reporting and the Activity

Test

2.55

Several submitters and witnesses voiced concerns about approved

providers' and parents' ability to comply with various administrative

requirements that require ongoing time and financial investment.[62]

Two particular concerns were identified: the need to report actual attendance;

and the Activity Test.

2.56

Australian Childcare Alliance argued that the need to report each

child's arrival and departure time would be burdensome and costly to providers:

Those services that choose to manually enter the data will

have to allow for a significant number of additional hours each and every week

that would be much better served supporting educators and children. In a

service with 100 children this will mean that the centre will need to manually

enter 1,000 attendance periods per week. This will increase human

resourcing costs for administration staff by 4 to 6 hours a week.[63]

2.57

For approved providers who seek a technological solution, ECA observed:

Not only is the implementation of the new scheme causing

increased administrative requirements, it also requires a significant financial

investment by service providers with the need to purchase/upgrade technology

and train administrative personnel.[64]

2.58

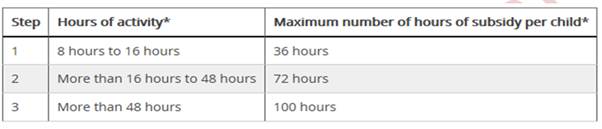

In relation to the Activity Test, submitters and witnesses argued that

childcare affordability will be affected by parents having to meet a

three-stepped activity test. Parents will only receive subsidised child care

for the number of hours engaged in a recognised activity each fortnight (Figure

2.4).[65]

Figure 2.4: Child

Care Subsidy, Activity Test, per fortnight

Source: Department

of Education and Training, 'Child Care Subsidy – activity test', https://www.education.gov.au/child-care-subsidy-activity-test-0

(accessed July 2018).

2.59

ECA emphasised that this is not conducive to achieving the best developmental

outcomes for children:

ECA believes that there is a very strong case for providing

all children with access to at least two days a week of early learning,

regardless of their parents' workforce participation, to achieve their best

development outcomes...the benefits are significant and ongoing for children

from disadvantaged backgrounds in particular. Two days per week can also

provide stability for families supporting employment preparation, searching and

transition and would make the CCS system simpler for parents to navigate,

especially though who are already managing complexity in regards to their

employment situation.[66]

2.60

ELACCA and CCCA described the new funding arrangements in terms of

missed opportunities and, similar to ECA, stated that the new system is complex,

onerous and will adversely impact children from disadvantaged and vulnerable

backgrounds. ELACCA submitted:

The need for documentation of activity, a random audit

process and the associated risk of accumulating a debt will likely result in

families choosing to withdraw their child from, or not enrol their child in,

early learning. As a result, the policy intent of workforce participation

and/or early learning outcomes of the CCS in all likelihood will not be

achieved. In particular, Australia's children experiencing vulnerability and

disadvantage, who in the absence of early intervention will potentially require

more costly interventions in the future, are most likely to be denied access.

The cost of administering the activity test far outweighs the benefits

received, and future costs incurred.[67]

Department response

2.61

A departmental representative indicated that families generally do not

use childcare when it is not subsidised: 'it's very expensive without a

subsidy'. The officer agreed with Ms Gagnon that families could decrease their children's

hours in care but also suggested that the ECEC sector might address this

accessibility issue by restructuring their care sessions:

The minister has said quite openly, so it's government

policy, that, particularly for the low-income families who get 24 hours per

fortnight, yes, that is definitely one 12-hour session per week. It's also two

six-hour sessions per week...some in the sector are already considering, for [a young]

cohort, offering two six-hour sessions.[68]

2.62

The Department recognised a need to minimise administrative requirements

for parents, which is to be achieved through improved data/information sharing

and IT systems (Child Care Subsidy System, CCSS). The new systems are intended

to provide 'a simple and easy user interface...and significant time saving

benefits...when applying for fee assistance and reporting change in circumstances'.[69]

2.63

The Department assured the committee that it would be closely monitoring

implementation of the Child Care Subsidy. Further:

A Post Implementation review is planned, and will be

completed within 2 years following implementation. This review will, amongst

other things, examine any regulatory burden of the package against the benefit

for families.[70]

Committee view

2.64

The committee acknowledges that current Australian Government ECEC

policy supports multiple policy objectives. The committee recognises the

importance of these objectives and the evidence indicating that there are

significant returns on investment in ECEC by promoting maternal workforce

participation among families from low socio-economic backgrounds and the

development of children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Nonetheless, the

committee agrees with the CIS's overarching suggestion that unnecessary and/or

inefficient red tape should be identified and eliminated.

2.65

The committee heard that implementation of the Child Care Subsidy is

causing some difficulties for the ECEC sector, as well as Australian families

using services. The committee is concerned that there have been transitional

issues for a significant number of families, who might now be impacted by

issues of affordability and accessibility. Further, the committee has heard

that several administrative requirements will be burdensome and ongoing, an

alternative to but not a simplification of the previous arrangements.

2.66

The committee notes that the Department will be monitoring the situation

and encourages it to proactively address issues as they arise, including

through consideration of the matters raised in this report. The committee expects

to see more thorough consideration and reduction of red tape throughout the

ECEC sector in the Department's next annual report in pursuance of the

Deregulation Agenda.

2.67

The committee is not persuaded that Australian Government fee assistance

is sufficiently well targeted, notwithstanding recent reforms. If the objective

of assistance is to increase maternal workforce participation, it should be

tailored to the demographic and occupational groups least likely to return to

work without assistance, and from which the economy receives the most benefit.

If the objective is to assist disadvantaged children, this should also be reflected

in the targeting. The committee heard no evidence that these aspects had

even been considered.

Recommendation 6

2.68

The committee recommends that the Department of Education and Training and

the Department of Jobs and Small Business report in greater detail on the

regulatory effect of implementing the Child Care Subsidy, including in relation

to Activity Test.

Recommendation 7

2.69

The committee recommends that the Australian Government review the

objectives of fee assistance to ensure that it is actually targeting maternal

workforce participation and children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Concluding comment

2.70

Some stakeholders suggested that the committee might find it more useful

to conduct its inquiry after implementation of the Child Care Subsidy on 2 July

2018. However, the committee is of the view that there are a broader range of regulatory

issues meriting examination, as highlighted in this report. The committee trusts

that its findings and recommendations assist the Department to finesse the childcare

reforms and provide Australian families with a better ECEC system that more

fully supports the viability of the sector.

Senator David Leyonhjelm

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page