Chapter 3

Commonwealth hospital funding

The 2014 budget did

serious damage to Commonwealth-state relations and the confidence with which

states could plan and manage health services. It did this by abrogating an

agreement about public hospital funding which had been signed by governments of

all political persuasions and unilaterally imposing a new funding model on the

states.[1]

Dr Stephen Duckett,

Director, Health Program, Grattan Institute

Introduction

3.1

The previous chapter provided the historical context of hospital funding

in Australia, and the struggle to find an agreement between levels of

government about funding responsibility. As noted in Chapter 2, a forum for

cooperation between federal, state and territory governments was achieved in

2011 when all parties signed the National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA). As a

result of this agreement, long term funding certainty, through until at least

2024-25 was achieved for hospital funding.

3.2

This chapter examines the impact of the Coalition Government's decision

to cease the funding mapped out under the NHRA. The effects of this decision,

made in the highly criticised 2014-15 Budget, have reached further than just

the removal of funding. This chapter also looks at:

-

the need for a mechanism that promotes cooperation between state

and federal governments on hospital funding and planning;

-

missed opportunities to promote reform in hospital funding;

-

the need for long-term, sustainable funding which allows for

workforce planning and infrastructure development; and

-

issues that have emerged or been exacerbated by the removal of certainty

in hospital funding.

2014 changes to Commonwealth hospital funding

Unsustainable health spending myth

3.3

A key element in the Coalition Government's justification of the cuts to

hospital funding was the argument that government expenditure on health was

unsustainable.[2]

The same argument was used to justify the $7 co-payment policy, later scrapped,

and the continuing freeze on MBS indexation.[3]

3.4

This argument has been widely disputed. In its Public Hospital Report

Card 2015, the Australian Medical Association (AMA) observed in relation to

the Coalition Government's health and hospital funding cuts:

The Government has justified its extreme health savings

measures on the claim that Australia’s health spending is unsustainable. But

Australia’s health financing arrangements are not in crisis.

In 2012-13, Australia had the lowest growth (1.5 per cent) in

total health expenditure since the Government began reporting it in the

mid-1980s. Without any specific Government measures, there was negative growth

(minus 2.2 per cent) in Commonwealth funding of public hospitals in 2012‑13,

and only 1.9 per cent growth in 2011-12. Our health sector is doing more than

its share to ensure health expenditure is sustainable.

Australia's expenditure on health has been stable as a share

of GDP, growing only one per cent over the last 10 years. Health expenditure

does not demand radical changes to existing services.[4]

3.5

Compared to other OECD countries, Australia spends just below the OECD

average for health funding. In 2015, Australia spent 9.7 per cent of GDP[5]

on health, while in comparison the US spent 16.4 per cent of GDP,[6]

Canada spent 10.2 per cent,[7]

and the UK spent 8.5 per cent.[8]

The OECD Health at a Glance 2015 notes that Australia's health

expenditure 'achieves good outcomes relatively efficiently'.[9]

2014-15 Budget cuts to hospital

funding

3.6

The 2014-15 Budget Overview incorrectly categorised hospital

funding as primarily a state responsibility:

State Governments have primary responsibility for running and

funding public hospitals and schools. The extent of existing Commonwealth

funding to public hospitals and schools blurs these accountabilities and is

unaffordable.[10]

3.7

On this argument, the government used the 2014-15 Budget to unilaterally

cancel the NHRA, signed by the states and Commonwealth governments in 2011, and

terminate various health-related National Partnership Agreements.[11]

States were 'expected to continue contributing to these arrangements at their

expense.'[12]

3.8

As part of the 2014-15 Budget, the Federal Government pledged that from

2017-18 Federal Government funding would revert to the former block funding

model based on indexation at the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and population

growth.[13]

Despite promising "no cuts to health", the Federal Government

projected that this new funding arrangement would save over $57 billion

between 2017-18 and 2024-5.[14]

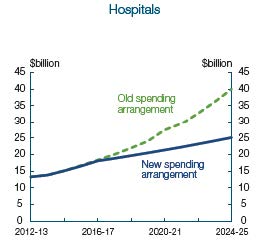

Figure 1, reproduced from the 2014-15 Budget Overview, shows the

government's projected reductions to hospital funding.

Figure 1—projected hospital funding cuts from the 2014‑15

Budget[15]

3.9

The Coalition Government's 2014-15 Budget was widely criticised. For

example Dr Stephen Duckett, Director of the Grattan Institute's Health Program,

told the committee:

The 2014 budget provided that future indexation to the states

would be in line with:

... a combination of the Consumer Price Index and population

growth.

If this is taken at face value, then the 2014 proposal is the

most parsimonious indexation arrangement that has ever applied to public

hospital funding grants.[16]

3.10

The Budget Overview went on to explain that the responsibilities of the

different levels of government would be the subject of a White Paper on the

Reform of Federation, to be completed at the end of 2015.[17]

The recently abandoned White Paper process is discussed further below.

Impact of hospital funding cuts on

states and territories

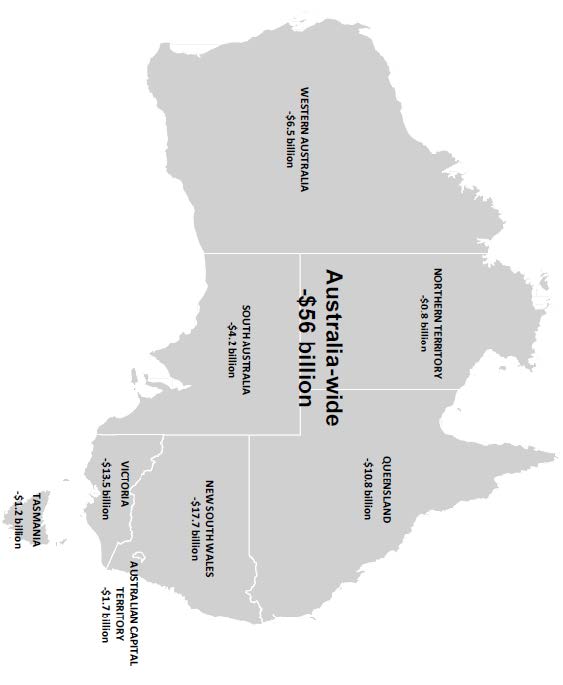

3.11

The committee sought a submission from the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO)

in order to gain a clearer understanding of the impact the Coalition

Government's funding cuts will have on each state and territory. The submission

is reproduced at Appendix 4. Figure 2, which is based on the PBO's findings,

shows the funding each state and territory will lose as a result of the 2014-15

Budget.

3.12

The funding cuts calculated in the PBO's submission relate to the

2014-15 Budget decision. These preceded the April 2016 COAG agreement to partly

reinstate funding out to 2020. While this COAG decision, discussed below, has

partially mitigated the 2014-15 Budget cuts, the $2.9 billion allocated across

three years (2017‑18 to 2019-20) is not adequate to address the $7.9 billion

shortfall over this same period created by the 2014‑15 Budget cuts.

3.13

During its inquiry, the committee has undertaken 52 hearings and held

public hearings and site visits in every state and territory. The following eight

chapters focus on each of the states and territories, detailing the extent of

the loss of funding and the issues which have arisen for each state. While

state governments have, to a large extent, provided short-term additional

funding to cover the immediate Commonwealth shortfall, this situation is

unsustainable long term. The loss of certainty over long term funding has also

meant that state governments are unable to forward plan workforce and

infrastructure and must subsist from budget to budget.

3.14

In addition to state-specific issues, there are also some issues caused

by the cuts to hospital funding that are Australia‑wide. These range from

high-level policy questions, such as the need for a mechanism for cooperation

between the states and federal governments, to grassroots impacts, such as

increased waiting times. These national implications are discussed throughout

this chapter.

Figure 2—Commonwealth hospital funding cuts from the

2014-15 Budget[18]

'Skin in the game'

Removal of the mechanism for state

and federal cooperation

3.15

As described in Chapter 2, the history of hospital funding in Australia

has been marked by a struggle to find a means of settling the respective

contributions of the state and federal governments. Of particular importance

has been the need to avoid short-term funding agreements and instead establish

sustainable long-term funding arrangements.

3.16

The Coalition Government's unilateral abandonment of the long-term NHRA

did more than remove Commonwealth hospital funding. It caused the loss of

goodwill in state-federal cooperation on health. Dr Stephen Duckett, Director

of the Grattan Institute's Health Program, described the 2014-15 Budget as

having done 'serious damage to Commonwealth-state relations and the confidence

with which states could plan and manage health services.' It did this by:

...abrogating an agreement about public hospital funding which

had been signed by governments of all political persuasions and unilaterally

imposing a new funding model on the states. The funding model promulgated in

the 2014 budget was presented in the budget papers as saving more than a

billion dollars over the forward estimates, with savings described as being in

the tens of billions over the ensuing decade. The words 'saved' and 'savings'

are an example of creative accounting. They are savings to the Commonwealth

budget only, but are not real savings to the public purse at all. Instead, they

are simply a massive and unsustainable transfer of costs from the Commonwealth

budget to state budgets.[19]

3.17

Dr Duckett categorised the NHRA as having 'dealt with some of the

dysfunctional aspects of federalism in health care'. The agreement had done

this by:

...creating an alignment of incentives. It made the

Commonwealth share directly in the costs of activity growth in health care,

which gave it an incentive to develop policies in its sphere that might

mitigate that growth. For example, the Commonwealth traditionally funds primary

care, while the states fund hospital care. Making the Commonwealth share

responsible for hospital funding gave it a stronger incentive to improve

primary care and reduce the number of avoidable and expensive hospital visits,

generating actual savings to the public purse. The 2014 budget removed that

alignment of incentives.[20]

3.18

Professor Mike Daube, Director of Public Health Advocacy Institute of

Western Australia at Curtin University, agreed with Dr Duckett. Professor Daube

described the situation after the 2014 cancellation of the NHRA funding

agreement as:

There is a whole lot in limbo now. I must say I think it

created distrust of central government, because if you have agreements that are

supposed to be lasting and suddenly they are cut then the state governments

which had to implement them will have people on contracts and so on, because

they would have assumed that the funding would continue. So it creates distrust

for them. It creates uncertainty out in the community...[21]

3.19

In the two years since the 2014-15 Budget, there has been much debate

about the role of the Federal Government in hospital funding. The Reform of the

Federation White Paper process has been part of that debate, although not to

the same extent as the ongoing criticisms of the 2014-15 Budget by groups like

the AMA.

Reform of the Federation White

Paper

3.20

The White Paper process was begun in the first half of 2014. Its main

objective was to 'clarify roles and responsibilities to ensure that, as far as

possible, the states and territories are sovereign in their own sphere.'[22]

Other objectives included reducing duplication between levels of government and

improving the efficiency of the federation.[23]

3.21

As part of the White Paper process, issues papers regarding various

aspects of the federation, including health and hospital funding, were produced

in the second half of 2014. However the Green Paper, which was to be released

in the first half of 2015, was not published until after it had been leaked in

June 2015.[24]

3.22

The 'discussion paper', as the leaked Green Paper was titled, lists five

options for reform of hospital funding. These range from a shared

responsibility for funding between the state and Federal governments to sole

funding responsibility resting on state and territory governments:

-

establishment of a benefit scheme similar to the Medicare

Benefits Schedule for all hospital treatments;

-

Commonwealth and states jointly fund individualised care packages

for chronic or complex conditions;

-

establishment of regional purchasing agencies to source health

services geographic areas;

-

Commonwealth becomes solely responsible for funding; or

-

states take full responsibility for public hospitals.[25]

3.23

It had been anticipated that federation reform would be part of the COAG

leaders' retreat on 23 July 2015, but the topic was not covered in the

communique for that meeting. Reform was discussed at the 11 December 2015 COAG

meeting, but leaders only agreed to further consideration of health funding at

the first COAG meeting of 2016.[26]

3.24

The White Paper on federation reform had been scheduled for publication

at the end of 2015, but this did not happen. Instead, a variation of the

options in the 'discussion paper' was put to the COAG meeting held on 1 April

2016, leading to an agreement to extend activity based funding to 2020

(discussed further below).

3.25

On 28 April 2016, the Prime Minister confirmed that the Reform of

Federation White Paper process had been scrapped, with no White Paper to be

released.[27]

The cost of the process was reported to be in excess of $5 million.

3.26

The Reform of the Federation White Paper website explains that:

...work to improve federal financial relations and the

transparency of government spending will be progressed by the Council on

Federal Financial Relations, and the Commonwealth, state and territory

Treasuries. A progress report will be brought to the next COAG meeting.[28]

Committee view

3.27

The Reform of Federation White Paper could have been a valuable process

for rebuilding state-federal relations after the disastrous 2014-15 Budget.

Instead, it has been significant waste of public money, and has only resulted

in returning state-federal relations back to the often combative forum of COAG.

April 2016 COAG agreement

3.28

On 1 April 2016 the Prime Minister, the Hon Malcolm Turnbull MP, faced a

hostile COAG meeting with states and territories concerned that the 2014-15 Budget

cuts to hospital funding would leave them unable to provide adequate hospital

services.[29]

The Prime Minister's proposal to the states was for an additional $3 billion

over three years for hospital funding, and the possibility that the states could

raise their own income taxes as funding for the longer term.[30]

3.29

While the income tax proposal was rejected by the states, COAG did agree

to a Heads of Agreement for hospital funding to run from 1 July 2017 to 30 June

2020 'ahead of longer-term arrangements'.[31]

Additional Commonwealth funding under the agreement was to be $2.9 billion

between 2017-18 to 2019-20, with growth capped at 6.5 per cent per year.[32]

The funding was to be provided primarily on the basis of activity based funding

and block funding under certain circumstances as set out under the NHRA.[33]

3.30

For their part in the agreement, states undertook to:

-

reduce demand for hospital services through better coordinated

care, particularly for people with complex and chronic diseases;

-

improve hospital pricing mechanisms; and

-

reduce the number of avoidable hospital readmissions.[34]

3.31

Although the April 2016 agreement provides partial and short-term

respite from the full force of the 2014-15 Budget funding cuts, the additional

funds in the agreement fall well short of the funding states would have

accessed under the NHRA. Instead of the NHRA's funding increase of 9 per cent

per annum, the states will see funding growth capped at 6.5 per cent, only 2

per cent improvement on the 4.5 per cent rate unilaterally imposed by the

2014-15 Budget.[35]

3.32

As discussed earlier, the additional $2.9 billion figure compares poorly

with the funding increase of $7.9 billion which would have flowed to the states

had the government not abandoned the NHRA.[36]

Need for long-term, sustainable funding

3.33

The April 2016 COAG agreement is welcome in that it is an improvement on

the hospital funding cuts contained in the 2014-15 Budget. However, it does not

go towards solving the larger problem: that a long-term funding agreement is

urgently needed to replace the NHRA which was abandoned in the 2014-15 Budget.

3.34

Since May 2014, state and territory governments have been forced to

operate in an atmosphere of uncertainty. States have faced the fact that Commonwealth

funding will decrease from the expected NHRA levels, and have been planning how

to mitigate the worst impacts of the loss. In South Australia, representatives

of the Department of Health and Ageing told the committee that their ability to

plan for future hospital services is compromised by the uncertainty around

funding:

It is clear that where the Commonwealth provides funding it

is welcome by the state. However, South Australia and SA Health is keen to

ensure that any benefits of reform measures...are durable in the long term. SA

Health's ability to undertake budgetary and service planning is compromised by

uncertainty created by the Commonwealth. Uncertainty remains about public

hospital funding. National Health Reform Agreement arrangements are unlikely to

be clarified until the release of the Commonwealth's white paper on the reform

of the federation in 2016.

SA Health looks forward to the ideas to be presented by the

Commonwealth about future roles and responsibilities for the health system as

part of this process. The present situation leaves the state bearing the risks

associated with growing demands on hospital costs and without the resources to

meet the expected growth. The state has had limited ability to influence the

full range of policy levers across the health system as a whole that drive

demand and public hospital services. This is not a sustainable process for the

health system in the future.[37]

3.35

In Victoria, representatives from the Department of Health and Human

Services told the committee that the Commonwealth is a 'critical partner' for

states in providing high quality hospital services:

The adoption of activity based funding as the basis for

Commonwealth funding contributions in 2011 signalled a commitment to carry a

share of hospital demand growth. To give that some perspective, Commonwealth

funding for public hospitals grew by an average of 6.6 per cent per annum for

the decade to 2010-11, growing to 7.1 per cent per annum to 2013-14. And growth

was estimated at 9.4 per cent beyond the 2013-14 forward estimates, based on

projected growth for Victorian public hospitals published in the 2013-14 MYEFO.[38]

3.36

The experience was similar in Queensland. Ms Kathleen Forrester, Deputy

Director-General Department of Health, told the committee that the NHRA had

provided a 'new and very different Commonwealth funding methodology' which:

...created the financial incentives for all levels of

government to work together to ensure the health system functions efficiently

and holistically to improve overall health outcomes. Furthermore, the

methodology accounted for all the main drivers of public hospital service cost

growth, because it is based on the actual increase in the volume of public

hospital services provided to patients.[39]

3.37

In comparison, the 2014-15 Budget decision to base funding on indexation

of CPI and population growth would 'break the link established...between

Commonwealth funding and efficient [growth] in public hospital services,

reducing the financial incentives for all aspects of the health system to work

together to improve outcomes.'[40]

The result would be:

...the major costs associated with other drivers of healthcare

demand would be borne by the states and territories, leading to an

ever-increasing share of state funding and a declining Commonwealth share. The

proposed funding model assumes that all population groups have the same need

for public hospital services. For example, it does not take account of the

greater health needs of Indigenous people and people from rural and remote

locations. This is particularly important for Queensland, which has the most

decentralised population in Australia. Nor does it take account of the ageing

population or the changing cost of service provision due to technological

advances.[41]

State issues

3.38

Chapters 4 to 10 of this report provide details of the impact of the

Federal Government's hospital funding cuts on each state and territory. While

the cuts had not been due to begin until 2017-18, the announcement of the

decision in the 2014-15 Budget included the removal of many of the National

Partnership Agreements which had provided funds to states and territories as

part of the NHRA. The effect of the funding cuts was therefore immediate, and states

had to begin planning for how to make up the shortfall in funds.

3.39

National Partnership Agreements, such as that relating to improving

hospital services, provided significant benefit, particularly to smaller states

and territories. In these cases, the funding cuts were felt most acutely. The

Northern Territory Chief Minister, the Hon Adam Giles MLA, described the loss

of the National Partnership Agreement funding:

Contrary to comments made by the Prime Minister today, the

pain from these front line service cuts will start being felt by the States and

Territories from July 1, 2014.

Let’s look at two examples. In 43 days time, the Territory

stands to lose $1.4 million in Federal funding for pensioner concessions and

health funding will be cut by $33.8 million or the equivalent of a minimum of

ten hospital beds.

These funding decisions will have a real and immediate impact

on the front line services offered to Territorians.[42]

3.40

Many states pledged to cover the immediate funding gap themselves;

however, that situation is not sustainable beyond the very short term. Issues

have already begun to emerge which demonstrate that without a state-federal

funding partnership, the states cannot adequately support Australia's

hospitals.

Committee view

3.41

Since its establishment in June 2014, the Senate Select Committee on

Health has seen other disastrous health policies from the 2014-15 Budget

scrapped or put on hold. But while the government has reversed ill-conceived

policies like the $7 co‑payment, the cuts to hospital funding have

lasted until 2016, when backlash from the states forced the government to make

a temporary and partial extension of funding.

3.42

Before the NHRA was agreed in 2011, respective hospital funding contributions

had been a struggle between the state and federal governments. The reforms to

hospital funding implemented by the previous government allocated virtually

equal responsibility for funding to the state and federal governments, and

created a mechanism for all parties to work together to ensure that funds were

used efficiently.

3.43

When the Federal Government unilaterally tore up the NHRA in the 2014‑15

Budget, the action set hospital funding arrangements back ten years. The

decision obliterated states' confidence in any federal-state funding

negotiation process. State hospital infrastructure and workforce planning, which

was appropriately based on the long-term funding agreement in the NHRA, was

thrown into uncertainty. State governments struggled to figure out how to make

up the shortfall in funding; many admitting that it would not be possible

unless funding was taken from other areas.

3.44

The defining achievements of the NHRA were to:

-

provide long-term funding and continuity of funding to enable workforce

and infrastructure planning;

-

create a forum for states and federal governments to work

together on hospital funding; and

-

establish an activity based funding model and the associated

national efficient price for hospital services.

3.45

The Government's 2014-15 Budget decision to allocate federal hospital

funding based on indexation of CPI and population growth, and unilaterally scrap

the NHRA, has:

-

destroyed state and territory government confidence in

negotiation with the federal government;

-

removed the best forum for state-federal partnership and

cooperation over hospital funding; and

-

created a shortfall in hospital funding that the state

governments are struggling to cover.

3.46

The Federal Government claimed in 2014 that the Budget measures were put

in place because health funding was unsustainable. In actual fact, the 2014-15

Budget has created the situation where hospital funding, with the burden shifted

significantly to the states, is unsustainable.

3.47

Although the COAG agreement of April 2016 has partially mitigated the damage

done by the 2014-15 Budget, the future of hospital funding is bleak. At best

the three year agreement has created space for the federal government to work

to rebuild the confidence of the states and establish a long-term agreement on

hospital funding, backed by fair, equitable and sustainable federal funding.

3.48

As the following chapters of this report show, the NHRA had been working

effectively to distribute funding in a responsible and equitable way to public

hospitals. The Coalition Government unilaterally scrapped the NHRA and replaced

it with what can only be described as an omnishambles or 'a situation that has

been comprehensively mismanaged, characterised by a string of blunders and

miscalculations'.[43]

3.49

The committee believes that there is only one way Commonwealth-state hospital

funding arrangements can be repaired, and that is to work through the NHRA. The

committee's recommendations go towards this goal.

3.50

In building on the NHRA, rather than the omnishambles created by the

2014‑15 Budget and the Government's misguided actions since, the

committee believes that the Federal Government needs be a partner with the

states in terms of hospital funding. Without 'skin in the game', there is no

incentive to work with state governments to ensure that funding is used

efficiently. The Federal Government needs to urgently build goodwill with the

state and territory governments, in order to create a solid foundation for any

future finding agreement.

Recommendation 2

3.51

The committee recommends that the Government reconstitute the National

Health and Hospitals Reform Commission or a similar body to review hospital

funding arrangements and build on the National Health Reform Agreement. This

process should be guided by the principles of equity, fairness, adequate

funding and long-term certainty to ensure the continuity of public hospital

services.

3.35 While the committee is pleased that the Federal

Government has made a temporary agreement with the states until 2020, which partially

restores the withdrawn NHRA funding, the committee believes that this is not sufficient.

Until recently, the Federal Government was actively working to remove the

mechanisms by which activity based funding was set up. The committee urges the

government to halt the closure of the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority,

and the other structures put in place by the former government to implement

activity based funding.

3.52

The committee supports activity based funding as the best means of

delivering limited funds in a manner that drives greater efficiencies and

provides a strong incentive for the Commonwealth to improve primary care and

reduce the number of avoidable and expensive hospital visits.

Recommendation 3

3.53

The committee recommends that the Government urgently give an

undertaking that the mechanisms for activity based funding, such as the

Independent Hospital Pricing Authority, and the other structures put in place

by the former government to implement activity based funding, will not be

dismantled.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page