Gender inequality and domestic violence

2.1

This committee has previously inquired into domestic violence in

Australia. In that report the committee noted that there is a complex range of

social and personal factors that can contribute to the incidence and severity

of domestic violence. As part of that report, the committee discussed the

gendered nature of domestic violence.[1]

2.2

The terms of reference for this present inquiry focus on specific

aspects of that discussion. This committee has been asked in particular to

inquire into and report on:

-

the role of gender inequality in all spheres of life in contributing to

the prevalence of domestic violence;

2.3

This chapter summarises the evidence received that was responsive to

this first part of the terms of reference.

2.4

Our Watch explained the term gender inequality:

Gender inequality is a social condition characterised by

unequal value afforded to men and women and an unequal distribution of power,

resources and opportunity between them. It often results from, or has

historical roots in, laws or policies formally constraining the rights and

opportunities of women, and is maintained and perpetuated today through

structures that continue to organise and reinforce an unequal distribution of

economic, social and political power and resources between women and men.

Gender inequality is [also] reinforced and maintained through

more informal mechanisms, many of which are strongly characterized by their

reliance on gender stereotypes. These include, for example, social norms such

as the belief that women are best suited to care for children, practices such

as differences in childrearing practices for boys and girls, and structures

such as pay differences between men and women.[2]

2.5

The South Australian Premier's Council for Women expanded further on the

consequences of gender inequality in society:

Social norms and gendered expectations shape the roles of men

and women, defining what is considered appropriate behaviours for each sex. In

many societies, women are viewed as subordinate to men and have a lower social

status, allowing men control over, and greater decision-making power than,

women. These differences in gender roles create inequalities and unless

challenged, over time they become entrenched and we, as a society, begin to

accept that unequal power and status is fair and just the way things are. These

beliefs become values that build attitudes; for example, that girls and women

are less important, that they think less and feel more than men, that men are

leaders, women caregivers. Paying women less for their work or assigning most

or all of child care to them, making it harder for them to get education and

job training, or keeping them out of 'good-paying' jobs (or any jobs at all)

are tactics, sometimes deliberate and sometimes unconscious, to keep the

existing power structures as they are.[3]

2.6

Submissions outlined the connection between gender inequality and

domestic violence:

Family violence is gendered in nature. While both men and

women can be victims and perpetrators of family violence, the overwhelming

majority of family violence is perpetrated by men against women. Further,

family violence experienced by women is usually more frequent and severe.[4]

2.7

Likewise, the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) observed:

Gendered violence is rooted in the structural inequalities

between men and women. It is both a cause and consequence of gender inequality.[5]

2.8

The AHRC referred to, and quoted from, the United Nations' Declaration

on the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993) (Declaration), which

recognises that:

[V]iolence against women is a manifestation of historically

unequal power relations between men and women, which have led to domination

over and discrimination against women by men and to the prevention of the full

advancement of women, and that violence against women is one of the crucial

social mechanisms by which women are forced into a subordinate position

compared with men.[6]

2.9

VicHealth, the Australian National Research Organisation for Women's

Safety (ANROWS) and Our Watch all referred to the findings on gender inequality

in Change the Story, which is a shared primary prevention framework.[7]

Part of the work for Change the Story involved identifying the drivers

of violence, including gender inequality:

There is now consensus in the international research that

examining the way in which gender relations are structured is key to

understanding violence against women. Studies by the United Nations, European

Commission, World Bank and World Health Organization all locate the underlying

cause or necessary conditions for violence against women in the social context

of gender inequality.[8]

2.10

The Tasmanian Government's submission also commented on the connection

between gender inequality and domestic violence:

While there is no single cause of violence against women and

the relationship between gender and violence is complex, it is now widely

recognised that gender inequality is a key driver of family violence, often in

intersection with other social inequalities such as age, race[,] ability and

social class.[9]

2.11

VicHealth reproduced a graph by the United Nations Development Fund for

Women demonstrating the relationship between the prevalence of violence against

women and gender equality (see Figure 1). The data, based on global indices of

gender equality shows that as equality decreases, prevalence of violence

against women increases.[10]

Figure 1: Physical and/or sexual intimate partner

violence and measures of gender equality[11]

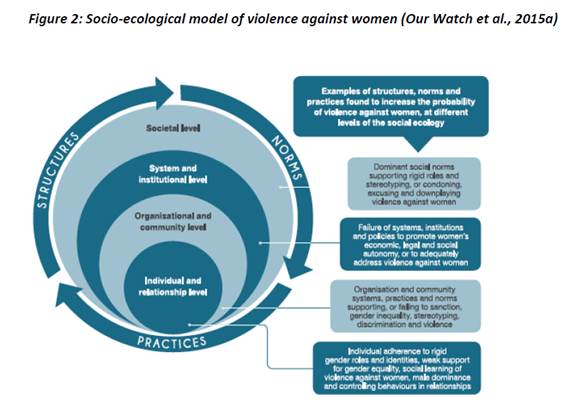

2.12

VicHealth explained a socio-ecological model of violence against women

showing the complex interplay between factors at various levels:

For example, at the societal and community levels, the risks

of VAW have been found to be higher when resources such as education and income

are distributed unequally between men and women, when women’s economic, social

and political rights are poorly protected and/or when there are more rigid

distinctions between the roles of men and women and between masculine and

feminine identities...

These factors which exist at the various levels of the

socio-ecological approach associated with higher levels of violence against

women include the ideas, values or beliefs that are common or dominant in a

society or community – called social or cultural norms. Norms are reflected in

our institutional or community practices or behaviours, and are supported by

social structures, both formal (such as legislation) and informal (such as

hierarchies within a family or community)...[12]

2.13

This is shown in Figure 2 below.[13]

2.14

Despite the research on the interaction between gender inequality and

domestic violence, according to the South Australian Premier's Council for

Women:

Across most sectors there is a poor understanding that gender

inequality in all spheres of life contributes to the prevalence of domestic

violence and other forms of violence against women.[14]

Gendered drivers of violence

2.15

Change the story notes:

Research has found that factors associated with gender

inequality are the most consistent predictors of violence against women, and

explain its gendered patterns.[15]

2.16

Change the story explains further the effect of these so-called

'gendered drivers':

The gendered drivers arise from gender discriminatory

institutional, social and economic structures, social and cultural norms, and

organisational, community, family and relationship practices that together

create environments in which women and men are not considered equal, and

violence against women is tolerated and even condoned.[16]

2.17

Change the story identifies the following drivers as those

consistently associated with higher levels of violence against women:

-

condoning of violence against women;

-

men's control of decision-making and limits to women's

independence;

-

rigid gender roles and identities; and

-

male peer relations that emphasise aggression and disrespect

towards women.[17]

2.18

Change the story also refers to another group of factors, the

'reinforcing factors':

[Reinforcing factors] while not sufficient in themselves to

predict violence against women, [can] interact with the gendered drivers to

increase the probability, frequency or severity of such violence.[18]

2.19

Those reinforcing factors are:

-

condoning of violence in general;

-

experience of, and exposure to, violence;

-

weakening of pro-social behaviour, especially harmful use of

alcohol;

-

socio-economic inequality and discrimination; and

-

backlash factors (when male dominance, power or status is

challenged).[19]

2.20

The Change the Story framework provides more detail on the role of rigid

gender roles and identities:

Levels of violence against women are significantly and

consistently higher in societies, communities and relationships where there are

more rigid distinctions between the roles of men and women – for example, where

men are assumed to be the primary breadwinner and women to be primarily

responsible for childrearing – and between masculine and feminine identities,

or what an ‘ideal’ man or woman is.[20]

Gender inequality in Australia

2.21

Women's Health West noted that in 2015, Australia ranked 36 out

of 145 countries on a global index measuring gender equality.[21]

Submissions compared this to previous years when Australia ranked 15th

out of 115 countries in 2006; 24th out of 136 countries in 2013; and

24th out of 142 countries in 2014.[22]

2.22

The Victorian Council of Social Service (VCOSS) explained that gender

inequality adversely affects women across all aspects of their lives:

[I]ncluding their educational and training pathways,

employment opportunities, work-life balance, opportunities to take positions of

formal leadership, health and safety, economic security, and social inclusion.

Gender inequality maintains the power and privilege held by men, and reinforces

negative messages about the value and status of women, increasing the

likelihood of experiencing violence.[23]

2.23

VCOSS continued:

In financial terms, women continue to do the bulk of unpaid

work across society, including caring for children, older parents or relatives

with disability or long-term health conditions, and housework. As a result

women of all ages have substantially lower labour force participation rates and

when they do engage in work it is more likely to be in part-time, lower paid,

insecure work. Even when working full-time, women earn lower average wages then

men. A gender pay gap of 18 per cent exists between full-time male and female

employees, equivalent to men earning an additional $284.20 per week.

Combined these factors place women at risk of financial and

housing insecurity, both while working and in retirement. Women are more likely

to live in low economic resource households, be unable to raise $2,000 in an

emergency, have little or no superannuation coverage or be financially insecure

in retirement.[24]

2.24

The Tasmanian Government referred to the lack of women in senior roles:

Women are underrepresented in leadership roles in both the

private and public sectors, in boardrooms and in parliaments, despite the fact

that women outperform men in higher education.[25]

2.25

The AHRC echoed this point, providing the following context:

The percentage of women on ASX 200 boards was 21.9 percent,

as of 31 January 2016. As of 2012, women held 9.7 percent of executive key

management personnel positions in the ASX 200; there were seven female CEOs in

the ASX 200; and in the ASX 200, women's representation in line management

positions was 6.0 percent and in support positions, 22.0 percent.[26]

2.26

The Women's Health West added:

In the current Federal parliament, only six of the 21 cabinet

ministers are women. In total, there are more than twice as many male federal

parliamentarians, compared to women (71 per cent male compared to

29 per cent female). The disparity is even wider in the number of men

compared to women holding ministerial positions (83 per cent male compared

to 17 per cent female). In 2015, women held only 39 per cent of the

2570 board positions on Australian Government boards and bodies, and

30 per cent of Chair and Deputy Chair positions on Australian Government

boards.[27]

Vulnerable groups

2.27

Gender inequality affects all women, but it does not affect all women

equally:

The intersection of multiple inequalities creates significantly

different lived experiences for women. Serious efforts to address domestic

violence must place gender inequality against a wider context of power and

multiple forms of inequality, including racial inequalities.[28]

2.28

The National Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (NATSILS) informed

the committee that any analysis of gendered stereotypes in family violence must

also pay attention to how gendered stereotypes intersect with racial

stereotypes:

Thus when acknowledging oppression associated with gender, it

is vital to also acknowledge that for many women this also intersects with

oppression caused by both historical and contemporary racism, often in

complicated and complex ways. Without such recognition, it is easy to forget

that gender stereotypes are not monolithic and that women from non-dominant

ethnic communities face additional challenges in terms of stereotypes. Assuming

that 'women' have a coherent group identity prior to their entry into social

relations, ignores how the ideologies of masculinity, femininity and sexuality

are inherently racialised.[29]

2.29

NATSILS highlighted that gender inequality is a contributing factor to

family violence rates in ATSI communities:

...gender inequality can be a factor which both contributes to

and compounds the victimisation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.

For example, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are significantly

disadvantaged in terms of entry into and promotion within the labour market,

which can leave these women marginalised, discriminated against and financially

dependent on partners. As has often been acknowledged, economic dependency can

make it extremely difficult for women to leave an abusive partner.[30]

2.30

Women from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds face

additional barriers in the pursuit of gender equality and a reduction in

domestic violence. The unique challenges facing CALD women were outlined by the

Women's Legal Services Australia, including:

-

Migration status. Women who are on temporary visas are particularly

vulnerable during domestic violence situations. They are often isolated,

without family support and entirely reliant on their abusive partner. They may

be fearful of leaving a violent relationship because of the consequences for

their migration status. Accessing legal advice, finding employment and

navigating the complexities of an unfamiliar court system are regular

challenges.

-

Knowledge of family law, family violence law and child

protection. Women often come from countries where their legal systems are

vastly different. They may have differing understandings on custody of

children, divorce settlements, dowry payments and legal protections against

domestic violence. Without timely access to legal information and advice that

is in a form that is understood by women, women are unable to effectively

access justice.

-

Access to interpreters. Women are often unable to access

appropriate interpreters once in the legal system. In some instances the same

interpreter must interpret for both parties. Women who require interpreters of

specific dialects or come from a small community where the interpreter is known

face even greater barriers.[31]

Attitudes to gender inequality and

domestic violence

2.31

In its submission, VicHealth referred to the findings of the 2013 National

Community Attitudes towards Violence Against Women Survey (NCAS):

This research found that the strongest influence on attitudes

towards violence against women among young people is their understanding of the

nature of violence and their attitudes towards gender equality.[32]

2.32

The NCAS investigates four areas:

-

community knowledge of violence against women;

-

attitudes towards violence against women;

-

attitudes towards gender roles and relationships; and

-

responses to witnessing violence and knowledge of resources.

2.33

The NCAS' findings in relation to attitudes towards gender roles and

relationships are particularly relevant to the terms of reference for this

inquiry. These findings are summarised below. In addition, Table 1 sets

out the findings for these areas compared to findings in the 2009 NCAS.

Attitudes towards gender roles and

relationships

2.34

The 2013 NCAS notes some 'encouraging results' in relation to attitudes

towards gender roles and relationships, namely:

Most Australians support gender equality in the public arena

such as workplaces.

Most acknowledge that women still experience inequality in

the workplace.[33]

2.35

However, there were also 'areas of concern':

More than a quarter [27 per cent] believe that men make

better political leaders.

Up to 28% of Australians endorse attitudes supportive of male

dominance of decision-making in relationships, a dynamic identified as a risk

factor for partner violence.[34]

|

|

2009

|

2013

|

|

Attitudes towards gender

roles in public and private life (% agree)

|

|

Men make better political

leaders

|

23

|

27**

|

|

When jobs are scarce, men

have more right to a job than women

|

11

|

12

|

|

University education is

more important for a boy

|

4

|

5

|

|

A woman has to have

children to be fulfilled

|

11

|

12

|

|

It's okay for a woman to

have a child as a single parent and not want a stable relationship with a man

|

60

|

66**

|

|

Attitudes towards decision-making in relationships

(% agree)

|

|

Men should take control in

relationships and be the head of the household

|

18

|

19

|

|

Women prefer a man to be in

charge of the relationship

|

27

|

28

|

|

Attitudes towards the status of women (% agree)

|

|

Discrimination against

women is no longer a problem in the workplace in Australia

|

11

|

13**

|

Table 1: 2013 NCAS findings on attitudes towards

gender roles and relationships.[35]

Attitudes towards violence against

women

2.36

In terms of the attitudes of violence towards women, the 2013 NCAS noted

positive trends:

Only 4% to 6% of Australians (depending on the scenario)

believe violence against women can be justified.

Since 2009 there has been a decrease in the proportion of

Australians who believe that domestic violence can be excused if the violent

person is regretful afterward.

Most do not believe that women should remain in a violent

relationship to keep the family together or that domestic violence is a private

matter to be handled in the family.

Since 1995 there has been a decrease in those who believe

that women who are sexually harassed should sort it out themselves.

Most support the current policy that the violent person

should be made to leave the family home.

Most agree that violence against women (both physical and

non-physical) is serious.

Since 1995 there has been an increase in the percentage

recognising

non-physical forms of control, intimidation and harassment as serious.

There has been a 7% decline since 2009 in the proportion of

young people who hold attitudes that support violence against women at the

extreme end of the spectrum. The decline is 10% in young men. Young people have

been the target of recent efforts to prevent violence against women.[36]

2.37

However, the NCAS also identified a number of areas of concern in

relation to attitudes towards violence against women:

Sizeable proportions believe there are circumstances in which

violence can be excused.

There has been an increase in Australians agreeing that rape

results from men not being able to control their need for sex, from 3 in 10 in

2009 to more than 4 in 10 in 2013.

Nearly 8 in 10 agree that it's hard to understand why women

stay in a violent relationship.

More than half agree that 'women could leave a violent

relationship if they really wanted to'.

Compared with physical violence and forced sex, Australians

are less inclined to see non-physical forms of control, intimidation and

harassment as 'serious'.

More than half agree that women often fabricate cases of

domestic violence in order to improve their prospects in family law cases and

nearly 2 in 5 believe that a lot of times women who say they were raped led the

man on and later had regrets.

Up to 1 in 5 believes that there are circumstances in which

women bear some responsibility for violence. There has been no change since

2009.[37]

2.38

Further information on the findings of the 2013 NCAS on attitudes

towards violence against women, including comparative results from surveys in 1995

and 2009, is set out in Appendix 2.

2.39

In summary, the 2013 NCAS made the following observation:

It is important to note that attitudes towards women are

fairly consistent across the population, regardless of your education, where

you live or what job you do. The survey found virtually no differences between

respondents in rural, remote, urban and regional areas or between states and

territories.[38]

2.40

However, the report continued:

[T]here are some differences in particular groups and places.

Groups who are most likely to endorse violence-supportive attitudes and who

have the poorest understanding of what constitutes violence against women are:

-

men, especially young men and

those experiencing multiple forms of disadvantage

-

younger people (16-25)

-

people from counties in which the

main language spoken is not English, especially those who have recently arrived

in Australia.[39]

2.41

In its submission, VicHealth noted the work to be done on improving

attitudes to gender inequality and violence against women:

The research indicates that significant efforts are required

to address young people's beliefs about gender roles in the family, household

and intimate relationships and also to provide skills for the development of

more equal and respectful relationships.[40]

National initiatives

National Plan

2.42

In its previous report on domestic violence in Australia, the committee

set out in detail the National Framework to address domestic and family

violence, specifically the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and

their Children 2010-2022 (the National Plan).[41]

2.43

The National Plan was endorsed by the Council of Australian Governments

(COAG) and released in February 2011. It is being delivered through four

three-year action plans. The First Action Plan operated from 2010-2013. The

Second Action Plan: Moving Ahead 2013-2016 was released in June 2014.[42]

2.44

The Second Action Plan advanced the issue of gender equality through:

-

national schemes to improve women's economic independence, such

as paid parental leave and access to child care;

-

national and local efforts to support women's leadership in

government, business and the community;

-

male champions and leaders speaking out against domestic and

family violence and sexual assault, and promoting the broader principles of

gender equality.[43]

2.45

In its submission, the Department of Social Services (DSS) informed the

committee that work was underway to develop the Third Action Plan, which was

due for release in mid-2016:

The Third Action Plan marks the half-way point for the

National Plan and will progress activities commenced during the First and

Second Action Plans. The Third Action Plan will continue to focus on the

drivers of violence, including gender inequality.[44]

Other initiatives

2.46

More broadly, in terms of the steps being taken to address domestic

violence, DSS advised the committee of the following government funding

announcement:

On 24 September 2015, the Australian Government announced

increased funding to address domestic and family violence through the Women's

Safety Package. This $100 million package contains a set of practical measures

to help keep women and children safe. This includes delivering better frontline

services, leveraging innovative technologies and providing education resources

to help change community attitudes to violence.[45]

2.47

DSS also reported on a national campaign to influence the attitudes of

young people towards violence:

In addition, a $30 million national campaign, jointly funded

with the states and territories, to reduce violence against women and their

children is expected to be launched in 2016. The campaign will focus on

galvanising the people (such as parents, other family members and peers) and

communities (such as schools, sporting and community groups) that surround

young people to positively influence their attitudes to violence and gender

inequality.[46]

2.48

DSS also mentioned the role of the COAG Advisory Panel:

The issue of domestic violence in Australia was elevated to

the highest political level and reducing violence against women remains a

priority for the Council of Australian Government's (COAG). An Advisory Panel

was established to support COAG, with full membership announced on 14 May 2015.

The COAG Advisory Panel is providing expert advice on how all Australian

governments can address violence against women and their children most

effectively.[47]

2.49

Our Watch indicated its view that the current challenge for governments

at all levels is to:

...scale up and systematise proven and promising, yet

small-scale, programs to the population level – enabling them to reach and

impact far greater numbers of people, and create the potential for the kind of

whole-of-population change that is needed.[48]

Primary prevention framework

2.50

As noted above,[49]

in addition to the National Plan, Our Watch, ANROWS and VicHealth have

developed Change the Story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of

violence against women and their children in Australia.

2.51

In November 2015, Change the Story was released. The framework:

...reinforces the direction outlined in the National Plan to

Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022, and seeks to

consolidate and strengthen the action already occurring around the country to

address the issue.[50]

2.52

The framework includes five actions to address the gendered drivers of

violence against women:

-

challenge condoning of violence against women;

-

promote women's independence and decision-making in public life

and relationships;

-

foster positive personal identities and challenge gender

stereotypes and roles;

-

strengthen positive, equal and respectful relations between and

among women and men, girls and boys;

-

promote and normalise gender equality in public and private life.[51]

2.53

Five supporting actions are also included:

-

challenge the normalisation of violence as an expression of

masculinity or male dominance;

-

prevent exposure to violence and support those affected to reduce

its consequences;

-

address the intersections between social norms relating to

alcohol and gender;

-

reduce backlash by engaging men and boys in gender equality,

building relationships skills and social connections;

-

promote broader social equality and address structural

discrimination and disadvantage.[52]

2.54

Following the release of the framework, Our Watch has indicated its

intention to develop a dedicated resource to guide the prevention of violence

against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children, which

will be released as a companion document to the framework.[53]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page