Key points

- The Bill would establish the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (NRFC) ‘to facilitate increased flows of finance into priority areas of the Australian economy’, by financing businesses, state and territory governments and other entities through concessional loans, equity, guarantees and a wide range of other financial instruments.

- The Bill requires that NRFC investments be solely or mainly Australian based, but the Australian Government would otherwise have full discretion to define ‘priority areas’ by disallowable legislative instrument. The Government could also specify almost all NRFC investment policy parameters, via non-disallowable legislative instrument (the Investment Mandate), though it could not direct the NRFC to undertake any specific, individual investment. Although Government commentary has focused on manufacturing and technology priorities and ‘rebuilding Australia’s industrial base’, the Bill itself does not mention any specific sectors, limit eligible priority areas or refer to ‘reconstruction’ (except in the title) or ‘rebuilding’.

- To date, Ministers have announced that the NRFC will fund up to $3 billion for renewables and low emissions technologies, $1.5 billion for medical manufacturing, $1 billion for value-adding in resources, $1 billion for ‘critical technologies’ (as defined on the separate List of Critical Technologies in the National Interest), $1 billion for advanced manufacturing and $500 million for value-adding in agriculture, forestry, fisheries, food and fibre. Consultation documents also name ‘medical science’, ‘transport’, ‘defence capability’ and ‘enabling capabilities’ (such as robotics, artificial intelligence and ‘quantum’) as priorities. These priorities are not legislated.

- The NRFC would be funded by an initial $5 billion in equity, and a further $10 billion by July 2029 in instalments (timing and amounts at the Government’s discretion; non‑disallowable).

- The NRFC’s target rate of return would be set in the non-disallowable Investment Mandate. Profit is expected in aggregate but not guaranteed and may come into tension with other policy goals and risk management concerns – as experienced by the Clean Energy Finance Corporation. The Bill does not require or aim for private sector co-finance (though the Explanatory Memorandum mentions ‘crowding in’ additional finance as one goal).

- The NRFC will be accounted at least ‘budget neutral’ in terms of the underlying cash balance, as the amount of equity injected will be defined as the NRFC’s initial ‘fair value’ as a financial asset on the balance sheet. However, the full fiscal costs, risk exposure and potential inflationary impacts of such ‘balance sheet financing’ are poorly captured by the underlying cash balance.

Introductory Info

Date introduced: 30 November 2022

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Industry, Science and Resources

Commencement: A single day to be fixed by Proclamation, or 6 months after Royal Assent at

the latest.

The Bills Digest at a glance

Background

- The

Australian Labor Party (ALP) committed to the $15 billion National

Reconstruction Fund on 15 November 2021 as ‘the

first step in Labor’s plan to rebuild Australia’s industrial base’.

- Arguments

for the proposal have focused on Australia’s low manufacturing self-sufficiency

and ‘economic complexity’. Opponents have focused on the risks created by market

interventions.

- Outside

Parliament, a broad range of interest groups have supported the proposal.

Purpose of the Bill

- The

main purpose of the National

Reconstruction Fund Corporation Bill 2022 (the Bill) is to establish the

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (NRFC) in order to ‘facilitate

increased flows of finance into priority areas of the Australian economy’.

Financial implications

- The

NRFC will be funded by a total $15 billion in equity injections, comprising $5

billion at commencement, and an additional $10 billion in total by instalments

before 2 July 2029. These amounts are set in the Bill, but the timing and

amounts of individual instalments would be at the Government’s discretion. The

equity injections would not be disallowable.

- A

recent publication by the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) notes that

conventional Budget reporting makes it complicated to evaluate the fiscal risks

and impacts of such equity investments.[1]

While the NRFC will nominally be at least ‘budget neutral’ in relation to the

underlying cash balance, the full fiscal impact and potential fiscal risk are

much more complicated to assess.

Key issues

Government discretion to

set – and reset – ‘priority areas’ and the Investment Mandate

- The

Bill and Explanatory Memorandum do not codify the ‘priority areas’ of the Australian

economy to be targeted for investment. The second reading speech does identify 7

priority areas[2];

however, this list should be considered indicative, because the Bill provides

that priority areas will be declared in a disallowable legislative

instrument.[3]

- Similarly,

‘reconstruction’ is not defined or mentioned in the Bill (apart from the title

and the name of the NRFC), although Government commentary has referred to

‘rebuilding Australia’s industrial base’.[4]

- The

Government says the NRFC is based on the model of the Clean Energy Finance

Corporation (CEFC).[5]

However, the CEFC’s investment focus is limited to ‘clean energy technologies’

as defined in the Clean

Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012, whereas the NRFC’s basic investment

focus will not be restricted to any specific sectors or technologies in primary

legislation. The target areas for investment will be defined later in delegated

legislation[6]

– and will have potential to be redefined in the same way. Though subject to

disallowance, this arrangement still gives the current and future governments considerable

power to redirect NRFC investment activity into evolving political and/or

policy priorities, mostly free of checks or constraints in primary legislation.

- The

Ministers may give the Board of the NRFC directions about the performance of its

investment functions, or the exercise of its investment powers, or both. The

directions together constitute the Investment Mandate. The Investment Mandate

will be a non-disallowable legislative instrument, giving the Government further

latitude to set high-level NRFC investment policy – though not to dictate

specific individual investments.[7]

Consultation on the Investment Mandate is ongoing.

Reporting and compliance

- For

equity interests, the NRFC must ensure that funded entities’ activities (where

the entity is not a state or territory or constitutional corporation) are all

constitutionally supported activities. Further, all investments made by

the NRFC must be solely or mainly Australian based, to be defined

according to guidelines which are yet to be developed by the Board. Assuring

that these requirements are being met will likely require compliance monitoring

and reporting beyond the reporting on funded entities’ activities in priority

areas of the economy.

No requirement for

co-finance

Purpose of the Bill

The main purpose of the National

Reconstruction Fund Corporation Bill 2022 (the Bill) is to establish the National

Reconstruction Fund Corporation (NRFC) in order to ‘facilitate increased flows

of finance into priority areas of the Australian economy’ (clause 3). The

NRFC is to be a statutory corporate Commonwealth entity for the purposes of the

Public

Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) (clause

11).

As defined by the Bill, the NRFC’s investment functions (clause

63) are to:

- provide

financial accommodation for purposes relating to any of the ‘priority areas’ of

the Australian economy, and

- acquire

equity interests in entities that carry on activities in a priority area of the

Australian economy.

The Bill and the Explanatory Memorandum do not specify the

‘priority areas’ of the economy. The Minister’s second

reading speech identifies 7 priority areas: value-adding in resources;

value-adding in agriculture, forestry and fishery; transport; medical science;

renewables and low-emission technologies; defence capability; and enabling

capabilities. However, this list could be considered indicative, because the

Bill provides that priority areas of the Australian economy will be

declared by the Ministers in a legislative instrument (clause 6). This must

be tabled in Parliament and will be subject to disallowance.[8]

Structure of the Bill

This Bill comprises 7

parts:

- Part

1 provides a simplified outline of the Bill and defines key terms, including

the range of investment mechanisms available to the NRFC under the categories ‘financial

accommodation’ (loans, guarantees, bonds, etc.) and ‘equity interest’ (shares

in companies, trusts, partnerships, etc.). It provides that ‘priority areas’

for NRFC investment will be defined by disallowable legislative instrument.

- Part

2 establishes the NRFC as a body corporate and sets out its high-level investment

functions and powers.

- Part

3 deals with the NRFC Board. It requires the appointment of a Board, sets out

the Board’s functions and sets procedural terms and conditions around Board

appointments, meetings and decision-making.

- Part

4 deals with NRFC staff. It sets out the terms and conditions of the

appointment of a CEO, including an outline of the CEO’s functions, and the

appointment of other NRFC staff. It provides that staff will be employed on the

terms and conditions that the NRFC determines in writing, and that the NRFC may

engage consultants to assist in the performance of its functions.

- Part

5 sets out financial arrangements for the NRFC, including the operation of its

Special Account, the credit to the Account of $5 billion on the day the

relevant section commences and the requirement to credit an additional $10

billion in total by mid-2029. It also sets limits on borrowing by the NRFC.

- Part

6 establishes the detailed investment functions and powers of the NRFC,

including constraints on the use of derivatives and guarantees, and the

requirement that investments be solely or mainly Australian based. It also sets

out the broad scope of the Ministers’ Investment Mandate (non-disallowable[9])

and how it will operate.

- Part

7 outlines miscellaneous provisions, including the NRFC’s ability to incorporate

or form subsidiaries; the requirement of, or permission for, the publication of

investment reports and other documents; the operation of delegated powers; and

a requirement for periodic reviews of the operation of the Act.

Background

Election commitment and policy announcement

The Australian Labor

Party (ALP) first committed to the $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund while

in Opposition, on 15 November 2021, describing it as ‘the

first step in Labor’s plan to rebuild Australia’s industrial base’. The

announcement said the Fund’s mission was to:

- create

secure well-paid jobs

- build

on our national strengths

- diversify

Australia’s industrial base

- develop

our national sovereign capability

- drive

regional economic diversification and development.

It further stated that the Fund would unlock potential

additional private investment of more than $30 billion – although the Bill does

not include any requirement for co-contributions from finance recipients, or other

private investment in NRFC-funded projects.

Since the May 2022 election, the Minister for Industry and

Science, Ed Husic, has elaborated on these goals. In his 29

November 2022 address to the National Press Club, Minister Husic stated:

We want Australia to be a country that makes things again.

It’s that simple. … Right now, Australia ranks dead last among OECD countries

in manufacturing self-sufficiency. We have the smallest manufacturing industry

relative to domestic purchases of any OECD country. Our consumption of

manufacturing output is nearly double our domestic manufacturing output. And we

have slipped in economic complexity from a modest 55 in 1995 to 91st in the

world in 2020. We import the bulk of what we need across sectors. And yet, the

signs are there that we can take a different path. …

The pandemic showed us that luck doesn’t last forever. We

need to be smart, too. And we’re not the only country to have realised this.

Around the world, industry policy is being remade before our eyes to shore up

local manufacturing capability. In the US, President Joe Biden is delivering on

Made in America commitments, with more than 100 billion dollars in announced

investments in electric vehicles, batteries and critical minerals, as well as

nearly 80 billion dollars in semi-conductor manufacturing. In our own region,

Singapore has unveiled a 10-year plan to boost local manufacturing by 50% ...

Tomorrow, I will introduce the legislation enabling the

establishment of the $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund … The National

Reconstruction Fund is one of the largest peacetime investments in our

country’s manufacturing capability in living memory … It will be empowered to

invest through a combination of loans, guarantees and equity, including with

institutional investors, private equity and venture capital. It will be

administered on the basis that it will achieve a return to cover borrowing

costs, and it will have an expected positive underlying cash impact.

Consultation

The Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR)

commenced a consultation process on 30 November 2022. Supporting materials

include a consultation

paper and virtual

consultation sessions. Input is sought by 3 February 2023 on ‘the

implementation of the NRF, including the investment mandate’; DISR also notes

that ‘this is one of several consultations that will inform the development of

the NRF’.[10]

The Bill has been referred to the Senate Economics

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 10 March 2023. Details are at the

inquiry webpage – National Reconstruction Fund Corporation Bill 2022.

Australian

manufacturing – Senate inquiry

The recent history of Australian manufacturing and its

challenges were well covered by the Senate Economics References Committee

inquiry into the Australian manufacturing industry.[11]

The Committee was chaired by Labor Senator Anthony

Chisholm, and its Final

Report (February 2022) provides a summary of the policy background to the

proposed NRF, including the view that manufacturing ‘is not just “another”

sector’, but rather has deep strategic importance for security and the national

innovation ecosystem (page 4). Foreshadowing Minister Husic’s comments above, the

report also expresses concern about Australia’s poor ranking for manufacturing

self‑sufficiency within the OECD (page 5) and growing manufacturing trade

deficit (page 6). The report also notes Australia’s dependence on unprocessed

resource exports, vulnerability to global supply chain disruptions and trade

tensions with China (pages 12–15) and low ‘economic complexity’ (page 19) – economic

complexity is discussed further below.

Notably, the Committee recommended the establishment of a

‘Manufacturing Industry Fund to provide a range of co-investment incentives to

the manufacturing industry in conjunction with the private sector’, and that

this fund should have ‘the flexibility to assist a range of manufacturing

sectors (including emerging sectors) and private entities, using a variety of

mechanisms, such as direct support for flagship projects, equity, concessional

loans, guarantees, and other means that deliver a positive return on investment’

(pages xi and 84). The Committee further recommended that the fund ‘particularly

look to accelerate Australia’s clean export industries, through funding of a

wide range of technologies such as hydrogen, green metals, and battery

manufacturing, and assist their transition to full market competition’ (pages

xi and 85). The NRFC would appear to address these recommendations.

In contrast, the ‘Dissenting Report – Liberal Senators’

(from page 93) warned:

The majority report proposes a number of recommendations

which would underpin a government driven interventionist approach in the

manufacturing sector. Such policies have not worked in the past and there is no

evidence to suggest that they will work in the future. The danger is that they

will distort the market and cause more harm than good … The work of the

Productivity Commission makes for sobering reading in this regard.[12]

In its September

2021 submission to the manufacturing inquiry, the Productivity Commission

questioned the role of Australian Government industry policy – other than

reducing protectionism – in the manufacturing sector’s historical decline. The

Productivity Commission also questioned whether this decline had had a negative

net impact on Australians’ welfare:

Manufacturing peaked as a share of the Australian economy in

the early 1960s… In large part this reflects the shift in consumer spending

from goods to services over recent decades. In addition, in an increasingly

competitive and interconnected global world, Australian manufacturing has faced

increased competition from imports, particularly from Asia. Like in other

advanced economies, the services sector now accounts for the bulk of the

economy … Given the similarity of this trend across developed economies, it is

difficult to discern the role that Australian policy has played in this

process. However, it is likely that the reduction in trade protection and other

forms of assistance contributed to the shift away from manufacturing …

The manufacturing sector still receives a disproportionate

share of assistance … Australia’s manufacturing sector continues to shrink

despite the assistance it receives.

The shift towards services has led some to comment about

adverse impacts on labour market outcomes and on the economy as a whole, but

such fears are not SUPPORTED by evidence. Compared to workers in the

manufacturing sector, workers in the services sector tend, on average, to be

paid slightly higher hourly wages and work slightly fewer hours, with the net

effect that total wages are roughly the same across the two sectors (PC 2021a,

pp. 15–17). And considering outcomes for the economy as a whole:

… the relative decline of manufacturing has not held back

living standards in Australia. On the contrary, once we began to reduce

manufacturing protection, and the burden it placed on more efficient and

productive activities – within manufacturing itself, as well as other sectors –

Australia’s exports took off and per capita incomes have risen faster than the

average for the OECD, taking us back to 6th in world rankings from 18th in the

late 1980s (Banks 2008, p. 11). [Pages 4–5]

The Commission’s submission warned against sectoral

approaches to industry policy, advocating instead for broad enabling reforms

and investments, with limited exceptions (pages 2–7).

This is the Commission’s longstanding position. For

example, its inaugural chairman, Gary Banks, warned in a 2011

speech to the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry that ‘At the top

of the list of perennially bad policy measures are those that promote

Australian industries by reducing imports’, whether through tariffs or

indirectly (page 3), and that ‘industry assistance that targets import

replacement and job creation in certain sectors is generally “bad” for

Australia’s productivity and prosperity’ (page 6).

Manufacturing

and economic complexity

A recurrent argument in debate about manufacturing policy

in Australia hinges on the relationship between manufacturing and a recently

developed metric called ‘economic complexity’, found to correlate with a

nation’s future economic growth prospects (globally, on average). Australia’s

economic complexity is low compared with its income level, because we export

few ‘complex’ products. This subsection provides background to these arguments.

In the late 2010s, Harvard University researchers

developed a metric called the ‘Economic Complexity Index’ (ECI), based on

research indicating that ‘development requires the accumulation of productive

knowledge and its use in both more and more complex industries… Countries

improve their ECI by increasing the number and complexity of the products they

successfully export.’[13]

For example, the most complex products include photography

equipment, semiconductors and ‘machines to extrude, draw, [and] cut manmade

textile fibres’, while the least complex products include metal ores and

concentrates, cocoa beans, cotton and petroleum oils. More complex products

have higher ‘value added’ and require many additional processing and

manufacturing steps following the extraction of raw inputs.

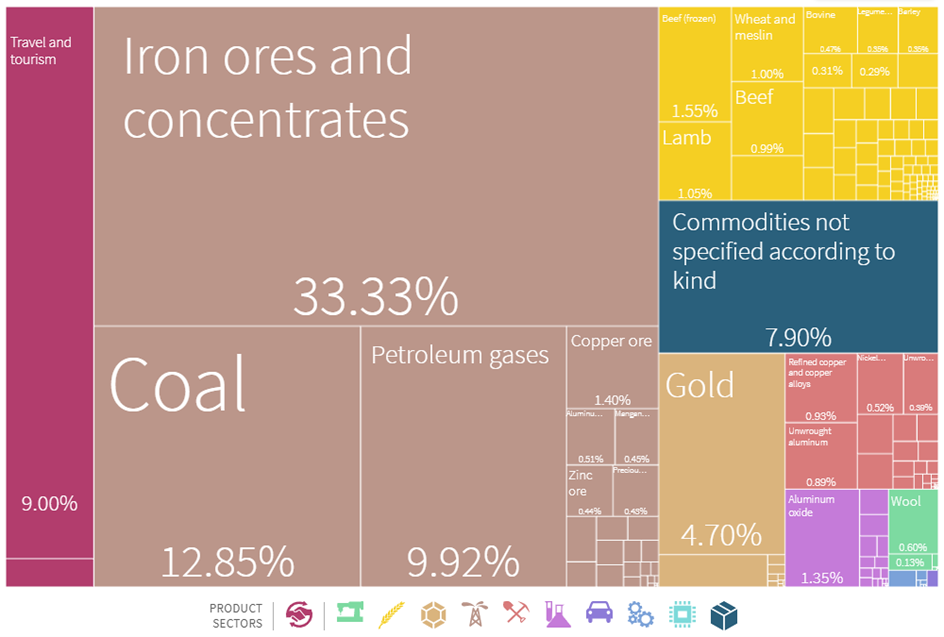

Australia’s exports are dominated by unprocessed or only

lightly processed raw materials, resulting in a low ECI (however complex the

extraction process may be) – see Figure 1.

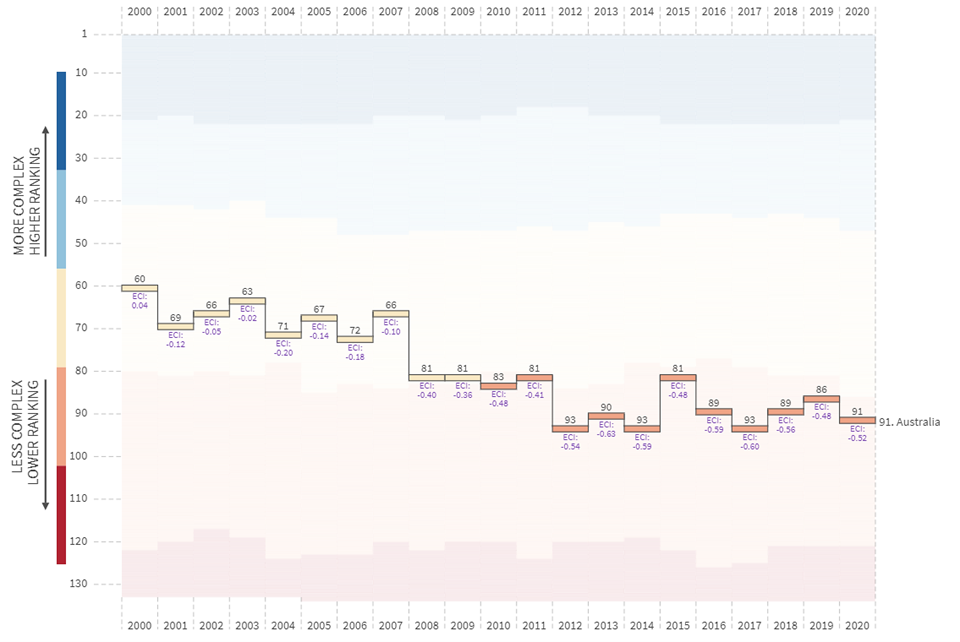

Australia’s ECI is currently ranked 91st out of the 133

countries assessed by the Harvard team (see Figure 2), indicating our exports

are slightly less complex than those of Kenya (90th), Laos (89th) and Pakistan

(88th) and slightly more complex than those of Namibia (92nd), Bangladesh

(93rd) and Tajikistan (94th). Among countries at economic development levels comparable

to Australia’s, but which also enjoy strong natural resources-based exports,

Canada’s ECI is ranked 43rd, and New Zealand’s 53rd. Japan, Switzerland,

Germany, South Korea and Singapore have the highest ECI; in general, developing

nations in Africa have the lowest.

Figure 1 Australia’s net export flows, 2020

Source: ‘Country Profile: Australia’, The Atlas of Economic Complexity, The Growth

Lab at Harvard University.

Figure 2 Australia’s Economic Complexity Index, 2000 to 2020

Source:

‘Country & Product Complexity Rankings’, The Atlas of Economic Complexity, The Growth

Lab at Harvard University.

Some see Australia’s weak ECI results as grounds for

government investment to revive domestic manufacturing. For example, in August

2022, the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre urged that ‘[m]anufacturing

is the answer to improving Australia’s falling complexity ranking’. University

of Technology Sydney Emeritus Professor Roy Green warned that ‘the truth is

we sustain a first‑world lifestyle with a third-world industrial

structure’:

This was the message of the Harvard Atlas of Economic

Complexity, which ranked Australia at the bottom of the Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for ‘complexity’, as measured by

the diversity and research intensity of its exports. It is also the logical

endpoint of the theory of ‘comparative advantage’, which asserts that we

maximise gains from international trade by exploiting our abundant natural

endowments in return for imported consumer goods from places that produce them

more cheaply.

Even if this theory was true in the past, it no longer holds

in a world where manufacturing is undergoing massive transformation in a

‘fourth industrial revolution’, encompassing robotics and automation,

artificial intelligence, data analytics and machine learning.

The ECI results also have traction within economic policy circles

of the ALP. In a March

2018 speech to the Insurance Council of Australia, titled ‘Is the Australian

economy too simple?’, Dr Andrew Leigh (now Assistant Minister for

Competition, Charities and Treasury) warned that:

… while some specialisation is good, too much can create

excess risk… Just like a worker who only has a single skillset, a country that

makes just a few products takes on a lot of risk in the world economy. …

But just as the proof of the pudding is in the eating, the

proof of any growth theory is how it predicts growth. And anyone who wants to

airily dismiss the Atlas of Complexity needs to explain the fact that it

has a pretty good track record of forecasting past economic growth across

nations …

For the economy as a whole, it’s vital not just to think

about how to lift up the best performers, but also how to improve the quality

of the economic ecosystem. The complexity approach isn’t perfect, but it is a

reminder that we have a lot of our national eggs in just a few baskets. Or, if

you prefer the more literary metaphor – we have too few Scrabble letters.

Harvard’s ECI metric also has sceptics. A 2019 Business

News article, titled ‘Harvard’s

complexity call way too simple’, argued Australia’s decline in ECI has been

‘driven more by the success of one sector’ – mining and LNG – ‘than the failure

of others’. It noted that despite the decline in ECI, Australia ranked very

well within the OECD for both exports growth and GDP growth, and that its highly

successful mining sector is among the most automated and efficient in the world

– that is, considerable implicit ‘complexity’ is hidden in Australian resource

extraction, even if the export itself is ‘simple’ metal ore. The article further

criticised the Harvard researchers’ recommendation that Australia consider

strategic investments in the manufacturing of transmission shafts,

compression-ignition internal combustion engines, forklift trucks and vehicle

bodies ‘despite three decades of gradual decline in the country’s car industry

due to lack of competitiveness’.

Sectoral

industry policy: strategic development or ‘picking winners’?

Minister

Husic’s 29 November 2022 Press Club speech foreshadowed an unapologetically

interventionist approach to industry policy:

Now, among some in the community there is still this

rusted-on sense that when it comes to industry policy, governments should not

be ‘picking winners’. That governments should only be considered as investors

of last resort, intervening when the market has failed. This is a diminished

view of the role of government. And, a missed opportunity. Governments can and

should strategically and thoughtfully invest in the industries of the future.

This shows a difference in tone from orthodox warnings

about the risk of market distortions when governments ‘pick winners’, as

offered over many years, for example, by institutions such as the Productivity

Commission. The Productivity Commission’s Trade

and Assistance Review 2020–21 warned that budgetary assistance (such as

grants and subsidies) to industry, even when ‘motivated by a desire to address

market failures’, nonetheless ‘distorts resource allocation and encourages

rent-seeking behaviour which has its own direct costs and undermines innovation

and productivity growth’ (page iii). The Commission further warned that the

provision of budgetary assistance to individual firms or for particular

activities within an industry – at a high level, the model envisaged for NRFC financing

– ‘can provide recipient firms with a significant competitive advantage

(especially over other firms in their industry) and can be highly distortionary,

as resources – such as finance, labour or equipment – may be redirected away

from more productive businesses and activities that are not receiving the same

level of assistance from government’ (pages 9–10).

The Commission estimated that the manufacturing industry

had received more than $2.8 billion in net industry assistance from government

in 2020–21, and that this level of assistance was ‘disproportionately large’

relative to the industry’s value added[14]:

‘The manufacturing sector received 23.3 per cent of allocatable net assistance …

despite accounting for only 6 per cent of value added’ (pages 6–7).

For several decades, ‘small government’ has also been the

orthodox economic policy approach advocated by global development authorities,

such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – although in recent years, IMF

staff have aired concerns about the unintended effects of deregulation and free

market policies taken to excess.[15]

Globally, other intellectual challenges to the philosophy

of a relatively hands-off industry policy have included:

- the

rapid development of the so-called ‘Asian tigers’ through deliberate,

systematic government support for manufacturing and high-tech industry

development – termed ‘developmentalism’ or the ‘Developmental State’ approach[16]

- more

recently, the work of economists such as University College London professor

Mariana Mazzucato, whose 2013 book The Entrepreneurial State argued that

private sector investment in new technologies and industries only eventuates after

governments make the risky early‑stage investments[17]

- the

increasing urgency of reducing global carbon emissions, including through rapid

industrial transformation – regardless of fossil fuels’ economic efficiencies

in the very short term

- supply

chain disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Context of recent Australian Government industry

policy

The pivot towards interventionism – as signalled in

Minister Husic’s statements above – is a matter of degree, rather than absolutes.

The greatest differences from the Coalition’s recent approach appear to be the

quantum of funds to be invested ($15 billion, dwarfing previous manufacturing

initiatives) and the choice of funding model (concessional finance and equity

investments via an investment corporation, in place of direct grants and tax

incentives), not the pursuit of sectoral policy or ‘picking winners’ per se.

For example, the previous Coalition Government had provided

some support for domestic industries of ‘comparative’ or ‘competitive

advantage’ prior to the COVID-19 pandemic through Industry Growth Centres and

other policies. More recently, it also committed funding for manufacturing

sectors of ‘critical’ or ‘sovereign’ importance, in reaction to global supply

chain disruptions due to COVID-19 (see Appendix A). The Modern Manufacturing

Strategy (2020) committed more than $1.3 billion for domestic manufacturing

grants in ‘priority’ sectors.

There is also considerable continuity between the

‘priority areas’ as identified by the current Labor Government – in speeches if

not this Bill – and those previously endorsed by the Coalition, as well as in

the industry policy goals as elaborated in the Explanatory Memorandum to the

Bill, such as:

… to support, diversify and transform Australia’s industry

and economy to secure future prosperity and drive sustainable economic growth …

[T]o leverage Australia’s natural and competitive strengths, supporting the

growth of a vibrant and modern economy, better positioning industry to be

successful in a net zero economy and more resilient against supply chain

vulnerabilities … [E]ncourage private investment, making it easier for industry

to commercialise innovation and technology, supporting the development of our

national sovereign capabilities and driving regional economic diversification

and development… [A]ssist Australian industry to seize new growth opportunities

by providing finance for projects that add value, improve productivity and

support transformation … [H]elp create secure, high value jobs for Australians

and strengthen our future prosperity.[18]

Figure 3 (below) and Appendix A summarise targeted

industry sectors and flagship policies under previous governments, compared

with the proposed NRF.

Figure 3 Priority industry sectors for Australian

Government support under previous governments, versus proposed NRF ‘priority

areas’

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis based on the sources

referenced in Table 1, Appendix A.

Appropriateness of the

entity model chosen for the NRFC

Options for the organisational structure of a new Commonwealth

entity

To deliver a service or execute a function, governments

may decide that a suitable entity already exists, or that a new entity should

be created. There may be various reasons for establishing a specialist entity

rather than administering the program through an existing department or agency.

For a new entity, options include, but are not limited to, establishing a new

department, a committee, a company or a statutory agency (established by or

under an Act of Parliament, with a name that may include ‘commission’ or

‘corporation’).

The Department of Finance (Finance) provides guidance on

these options, and classifies Commonwealth entities into 13 categories.[19]

Intended as a summary of Finance guidance, a Parliamentary

Library Quick Guide outlines the 13 categories and provides examples

of each category.[20]

A Finance

webpage provides a more detailed discussion of the key characteristics of

each category.[21]

Establishment of the NRFC as a corporate Commonwealth

entity (CCE)

The establishment of the NRFC as a statutory,

Budget-funded corporate Commonwealth entity (CCE) for the purposes of the PGPA

Act (category 1.2 in the Quick

Guide table) appears to be consistent with:

The Finance guidance compares CCEs with Commonwealth

companies.

Commonwealth

Governance Structures Policy (Governance policy): Governance structures

created through enabling legislation (eg a primary or a secondary statutory

body) have clearly defined purposes authorised by Parliament.

‘Types

of Australian Government Bodies’: A corporate Commonwealth entity is a body

corporate that has a separate legal personality from the Commonwealth. A

corporate Commonwealth entity can enter into contracts and own property

separate from the Commonwealth.

Corporate Commonwealth entities are still part of the

Australian Government. … Creating a corporate Commonwealth entity may be

suitable if:

-

the body will operate commercially or entrepreneurially

-

a multi-member accountable authority will provide optimal governance for

the body

-

there is a clear rationale for the assets of the body not to be owned or

controlled by the Australian Government

-

the body requires a degree of independence from the policies and

direction of the Australian Government.

Finance guidance suggests a company structure would not be

a good match for the proposed form and functions of the NRFC, which is intended

to make investments rather than pursue an entrepreneurial or business

enterprise in its own right. The guidance on ‘Types

of Australian Government bodies’ states:

Creating a Commonwealth company may be suitable if:

-

the body will primarily conduct commercial or entrepreneurial activities

and will generate profits for distribution to its members

-

the body will operate in a commercial or competitive environment (at

arm’s length from government)

-

the Australian Government is going the sell the body in the short to

medium term.

Further, the Finance guidance notes that ‘issues’ can

arise when using a company structure:

Lack of scrutiny

-

there is no formal opportunity for parliamentary scrutiny before a

company is established

-

the objects of a company may be amended by its members without

parliamentary scrutiny

-

a company can borrow and invest money without government approval.

Budget funding

-

Commonwealth companies may not be able to enter into multi-year

agreements if they rely on annual funding from the government. Lack of funding

certainty may affect their ability to pay debts when they fall due.

Public perception

-

there may be an assumption, or a public perception, that there is a

government guarantee for the operations of a Commonwealth company in the event

of its failure.

Taxes

-

a company is generally liable to pay Commonwealth, state and territory

taxes and charges, whereas enabling legislation may exempt a statutory body

from these taxes and charges.

In sum, establishing the NRFC as a CCE appears to be

consistent with guidance from Finance. Alternative entity types, such as a

Commonwealth company, appear to be less suitable.

Committee consideration

Senate Economics Legislation Committee

The Bill has been referred to the Senate Economics

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 10 March 2023. Details are at the

inquiry

homepage.

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

At the time of writing this Digest, the Bill had not been

considered by the Senate Scrutiny of Bills Committee.

Policy position of

non-government parties/independents

The Deputy Leader of the Opposition and Shadow Minister

for Industry, Skills and Training, Sussan Ley, has objected to the

omission of the space sector from the proposed NRFC priority areas, tweeting

on 10 November 2022:

The Dept of Industry has just confirmed that Space has been

abandoned as a priority in the Albanese Government’s National Reconstruction

Fund. This is a sad departure from the former Coalition Government’s commitment

to Australia’s space industry.

While not in reaction to the current Bill, the Dissenting Report

by Liberal Party Senators to the Final

Report (February 2022) of the Senate Inquiry into the Australian Manufacturing

Industry offered relevant comments:

Whilst we share the view expressed in the majority report of

the importance of the manufacturing sector to Australia, we disagree with several

key recommendations in the report …

A centrepiece of the recommendations contained in the

majority report is a so-called Manufacturing Industry Fund. Whilst not directly

referenced, this recommendation appears consistent with the Federal

Opposition’s policy to establish a $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund …

On the one hand, the majority report recognises the dangers

inherent in the government favouring particular sectors. On the other hand, it

then proposes measures which would involve investment (including the provision

of equity) in not just particular sectors, but specific businesses …

We do not support the establishment of a manufacturing

industry fund of the scope and nature proposed in the majority report. …

In terms of any government ‘co-investment’ in business

enterprises (i.e. the government taking equity positions in private sector

businesses), the following questions must always be asked:

- Why can’t the

particular venture attract equity investment or debt support; and

- If the private

sector will not invest its equity in the venture nor commercial lenders advance

sufficient debt funds, why should the Government risk taxpayers’ money?

In our view, the focus should be on government policies which

drive productivity and remove barriers to private sector investment. [Pages

93–95, emphasis added]

Among its 2022 election documents, the Liberal Party’s ‘Our

Plan for Modern Manufacturing’ (11 May 2022) further criticised the

NRF as an unfocused ‘magic pudding’, with ‘more than 30 top priorities’.

Positions on the cross-bench were unclear at the time of

writing.

Position of major interest

groups

Outside Parliament, a broad range of interest groups have

responded positively to the proposed NRFC, including: the Advanced

Manufacturing Growth Centre, the Tech

Council of Australia, quantum computing startup Q-CTRL, the Australian

Academy of Technological Sciences & Engineering, peak body AusBiotech,

the Medical

Technology Association of Australia, the Australian

Food & Grocery Council, Timber

Queensland, the Heavy

Vehicle Industry Australia, the Australian

Workers’ Union, the Business

Council of Australia and Deloitte.

AiGroup’s position on the NRFC was more cautious. On 25

October 2022, Chief Executive Innes Willox said AiGroup was waiting to see

details on the NRFC, but Budget ‘cuts

to a range of industry development programs including the successful Entrepreneurs Programme’ were ‘disappointing’.

There is also support from niche interest groups. The Business

Council of Cooperatives and Mutuals (BCCM) was ‘particularly pleased that

co-ops and mutuals are eligible to apply for funding under the National

Reconstruction Fund’. The Australian

Institute of Architects ‘note[s] the announcement to establish the National

Reconstruction Fund’ and ‘hope[s] for a national construction supply chain

focus on increasing Australia’s capacity to manufacture high-quality and

sustainable building materials, components and fittings.’

The Adelaide

Advertiser reported (24 March 2022) that although ‘Greater

incentives to manufacture locally would be welcomed … there’s a wide consensus

any government intervention must be careful and laser-like to prevent massive

industries from becoming inefficient and leaving taxpayers with a burden.’

Although it has not, to our knowledge, commented on the

proposed NRF, the

Productivity Commission’s September 2021 submission to the Senate Inquiry

into the Australian Manufacturing Industry restated its common warning

against sectoral approaches to industry policy outside certain narrow cases, as

discussed under ‘Background’.

Financial implications

How much

will be invested?

The financial impact statement in the Explanatory

Memorandum states that $5 billion will be provided to the NRFC from

commencement, with the remaining $10 billion to be made available by 2 July

2029 in instalments as determined by the Ministers – for a total equity

injection of $15 billion (as per clause 52).[22]

The Government will also pay $50.0 million over 2 years to DISR and Finance to

establish the fund.[23]

The initial equity injection will be offset, in small

part, by partially reversing or reducing Coalition spending programs,

particularly the Modern Manufacturing Strategy and Entrepreneurs Program.[24]

However, as these savings amount to approximately $500 million, against the $15 billion

commitment, the equity injections will need to be funded primarily by new debt.[25]

Which

sectors will be targeted for support? How much will they get?

The following

7

priority areas have been announced (further detail on what these areas

include is in the Government’s consultation

paper, at page 2), although these could be taken as indicative given that

the Bill provides that the priority areas will be defined later by legislative

instrument (clause 6):

- renewables and low emissions technologies

- medical science

- transport

- value-add in the agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors

- value-add in resources

- defence capability

- enabling capabilities ‘such as robotics, [artificial intelligence] and

quantum’.[26]

To date, the Government has also announced

that the NRFC will fund:

- up

to $3 billion for renewables and low emissions technologies – ‘Specifically,

under the Powering Australia plan, within the Reconstruction Fund, $3 billion

will be allocated to investing in green metals, steel, alumina, aluminium;

clean energy component manufacturing; hydrogen electrolysers and fuel

switching; agricultural methane reduction and waste reduction’[27]

- $1.5

billion for medical manufacturing

- $1

billion for value-adding in resources

- $1

billion for critical technologies – based on the new List of Critical

Technologies in the National Interest, which ‘will build on the 2021 List,

which featured 63 technologies across 7 categories: advanced materials and

manufacturing; AI, computing and communications; biotechnology, gene technology

and vaccines; energy and environment; quantum; sensing, timing and navigation;

and transportation, robotics and space’[28]

- $1

billion for advanced manufacturing

- $500

million for value-adding in agriculture, forestry, fisheries, food and fibre.

Clarifying

fiscal risks

The best resources on the potential fiscal impact and

transparency issues arising from equity-based financing mechanisms, such as the

proposed NRFC, are:

As explained by the PBO

in its report:

Alternative financing arrangements usually involve the

government providing the financial resources for a policy and receiving a

financial asset in return. …

With an equity injection, the government uses cash to invest

in a project, and it generally then has the entity undertaking the project as a

financial asset on its balance sheet. The initial value of the equity is

taken to be the amount that the government paid, so the initial

transaction does not have any impact on the government’s net financial worth

(or the fiscal or underlying cash balances). …

For policies funded directly, such as via a grant or direct

payment, almost all of the associated costs come from transactions, meaning the

fiscal balance or underlying cash balance impact of the policy is generally a

good indication of the overall cost of the policy. Policies implemented

using alternative financing arrangements, however, generally have some costs

that are characterised as transactions and others as revaluations. …

Revaluations can be substantial and affect the

government’s balance sheet and net financial worth, but are not fully reflected

in the fiscal or underlying cash balances. This means that the fiscal

and underlying cash balance impacts of policies that use alternative financing

arrangements are less likely to reflect the full cost to the government’s

balance sheet. [Pages 2, 12–13; emphasis added]

In the present case, the Government will initially inject

$5 billion into the NRFC, and in turn receive the NRFC as a ‘financial asset’

(nominally equal in worth to the value of the equity injection) on its balance

sheet. This will have a neutral budget impact in terms of the underlying cash

balance (UCB). However, consistent with the PBO’s above advice, ‘budget

neutral’ in terms of the UCB does not mean the investment is risk free,

or that it will be budget neutral in terms of the Australian Government’s balance

sheet position and net worth in the long run. The NRFC may not hold its initial

value as a financial asset. This will depend on the performance of its loan

portfolio and the success of the projects and enterprises in which it invests.

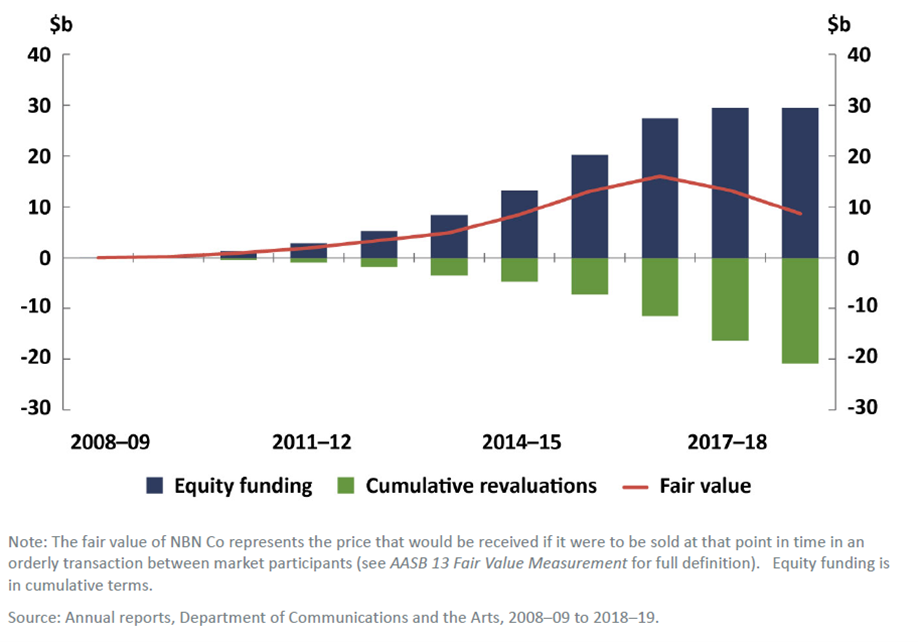

The PBO report highlights the example of NBN Co. It was

originally expected to be a ‘budget neutral’ $29.5 billion equity investment

that would eventually pay for itself, but was subsequently devalued

dramatically, decreasing the Government’s net worth – see Figure 3 below

(reproduced from Figure 3–1 in the PBO report). As the PBO summarises:

… the fair value of NBN Co has been consistently below the

cumulative amount of equity injected into the company … [T]he total equity that

has been invested in NBN Co is $29.5 billion. The most recent fair value

estimate of NBN Co, as at 30 June 2019, was $8.7 billion. The $20.8 billion

difference between the amount paid and the current fair value is a revaluation.

It reflects the extent to which the Commonwealth Government’s balance sheet has

directly deteriorated as a result of this investment as at 30 June 2019. By

definition, this impact is not captured in the fiscal or underlying cash

balances, though it is captured in net financial worth. … [However:] It is

important to note that the main budget documents show only the aggregated

effect of all revaluations across the general government sector, rather

than revaluations at an individual company or project level. [Pages 14–15;

emphasis added]

Figure 4 Fair value of administered investment in NBN Co since inception

(PBO analysis)

Source: PBO, Alternative Financing of Government

Policies: Understanding the Fiscal Costs and Risks of Loans, Equity Injections

and Guarantees, Report 01/2020 (Canberra: PBO, 2020), 14.

Further, while the Government may reasonably expect the

NRF to generate revenue through a return on its investments such as loans and

equity stakes in (hopefully profitable) businesses/projects, this outcome is

not guaranteed – and profitability has the potential to come into tension with

other policy objectives and prudential considerations.[29]

The experience of the CEFC demonstrates this possibility. The NRFC is modelled

on the CEFC.[30]

While the latter has delivered a positive return in most financial years since

its inception, it has never met its statutory rate of return target as

stipulated in its investment mandate; and its economic impact, though

considered positive, has proven difficult to quantify.[31]

CEFC fund managers have pointed to the difficulty of

achieving the rate of return directed by the Government from the commercial

opportunities available within the (shallow) Australian market, unless it

accepts a high risk of substantial investment losses.[32]

The ANAO’S audit of CEFC Investments (published 2020) further noted the

challenges with forecasting actual returns ahead of time, noting the CEFC’s

advice that actual rates of return can only be confirmed at the end of a

potentially long investment cycle (with some debt extending to 17 years), that

loan cash flows are uneven over time and that high-risk venture capital returns

won’t be known until the investments are either sold or written off.[33]

Performance audits and reviews of other

investment funds subject to Government-mandated economic objectives and rates

of return[34]

also point to challenges around measuring the delivery of intended economic

outcomes and the realisation of public benefit.[35]

Further, as discussed during the 19

August 2021 hearing of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (Inquiry

into Alternative Financing Mechanisms), the threshold

for classifying an equity‑backed Government entity as a ‘financial asset’

is quite low. Moreover, as the threshold is usually evaluated at the entity

level – that is, it would only need to apply to the NRFC as a whole, not to all

of its investments – it does not preclude Government use of an otherwise

profitable entity to channel funds to unprofitable types of investments:

Senator SCARR: When is something a financial asset? My

understanding is that it needs to be expected to deliver a positive real rate

of return. … So if it delivers $1 of positive return on a real basis it can

still be considered a financial asset. …

Dr Helgeby [Parliamentary Budget Officer]: … It is,

as you say, a low threshold – it is simply that you have an expectation of a

positive return; and there is a level of interpretation around that. …

Senator SCARR: … In paragraph 4.1.2 [of the 2020

PBO report], you quote from the business case for Inland Rail, … that Inland

Rail ‘would not generate enough revenue to provide a return on its full

construction cost’. … If there’s a large infrastructure project which, by

its own business case, is not going to generate the return to pay for its

construction … how should investment in such a project be treated? … Because if

the project’s never going to make a positive real rate of return, I struggle

with how you can treat investments into the project as equity as opposed to

being grants.

Dr Helgeby: In that case, the investment is into

the entity, the ARC [sic; the Australian Rail Track Corporation], and

the test is being applied at that level rather than at the individual project

level in that particular case … in essence, the reason why the payment that

is associated with the construction of Inland Rail is treated that way is

because it’s actually a payment to the entity. …

Senator SCARR: The entity has a number of different

projects, a number of different cash-generating units, but we’re simply

putting money into the entity, so we just don’t have the visibility or

transparency around how that investment is being made on a project-by-project

basis because it’s being made at an entity level. Is that correct?

Dr Helgeby: Yes, that’s right. [Pages 3–4; emphasis

added]

Such issues have affected the NSW Government’s recent establishment

of the Transport Asset Holding Entity (TAHE) as a statutory state-owned

corporation. The performance

audit of the ‘Design and implementation of the Transport Asset Holding Entity’

by the Audit Office of NSW (published 24 January 2023) noted the NSW

Treasury’s goal of creating ‘an entity that could generate a return on

investment, as this meant that government investment in transport assets could

be treated as equity investments, rather than a Budget expense’. During design

of the entity, this goal came into tension with other policy objectives, such

as rail safety, resulting in ‘an unnecessarily complex outcome that places an

obligation on future governments to sustain’, because the revenue needed to

maintain that budgetary status is subject to doubt. The NSW Audit Office warned

of ‘significant uncertainty as to whether the short-term improvements to the

Budget can continue to be realised in the longer-term’ (page 2). While many of

the NSW auditors’ concerns relate to the specifics of that case, a key

similarity to the present case is that the budgetary benefits of classifying the

initial TAHE and NRFC financing as equity injections were booked before these

entities had been legislated, or their operating models finalised.

Such risks are not transparent from the supporting

material for this Bill – with the Explanatory

Memorandum merely stating that ‘The Corporation is expected to generate

revenue from its investments’ (page 4). In its first Budget, however, the Government

was forthright in describing nuances and risks associated with alternative

financing mechanisms in general. The Budget

Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1 October 2022–23 elaborated:

Cashflows from the acquisition of financial assets, like

equity or loans receivable, do not impact on the underlying cash balance

(UCB) provided the Government is expected to recover its investments. The

acquisition of financial assets for policy purposes does reduce the headline

cash balance (HCB) and requires additional debt issuance (assuming no available

cash reserves), increasing gross debt. …

Establishing investments expected to earn a market rate of

return does not initially change net financial worth (as an increase in

gross debt is offset by an equal increase in financial assets). The impact

on net debt depends on the nature of the asset acquired. Debt-like

financial assets are included as assets in net debt, offsetting debt issuance.

For example, a (non-concessional) loan does not increase net debt as it

is considered a debt-like asset, whereas equity investments do increase net

debt.

Where the value of the asset acquired is less than the

amount borrowed (as for example with concessional loans) net financial

worth is reduced. There is no immediate UCB impact from the

acquisition. UCB worsens over time if interest payments on debt exceed

investment returns. Assets and liabilities are also subject to

revaluations each reporting period. …

Risk management is critical to balance sheet investment. Debt

financed asset accumulation improves the budget when returns exceed borrowing

costs, but also increases the Government’s risk exposure. Some risks are

specific to the investment (such as borrower specific risks of defaults or

delivering poor value for money by competing with the private sector for

investment opportunities). Others are economy wide (such as changes in interest

rates, economic activity, and business profitability). [Page 99; emphasis

added]

Implications

for Budget transparency and Parliamentary scrutiny

The Joint

Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) inquiry into alternative

financing mechanisms explored the implications of the above complexities

for Budget transparency.

The PBO stressed to the Committee that use of the balance

sheet, such as equity financing, is not ‘off-budget’ financing, and that

it can be an appropriate policy choice. In his 19

August 2021 testimony to the JCPAA, the Parliamentary Budget Officer (Dr

Stein Helgeby) explained that with regard to loans, equity injections and

guarantees:

My personal preference is to refer to these mechanisms

together as ‘balance sheet financing’. It’s important to say that financing

activities in this way is not off-budget financing. They turn up in the

balance sheet rather than in the operating statement or the cash flow

statement. The term ‘off-budget’ is, in fact, not very helpful, but it does

point to the fact that discussion of government finances is often focused on

only one dimension [the UCB], and I see it as part of our role at the PBO to

move beyond this one-dimensional view. [Page 1, emphasis added]

Dr Helgeby discussed circumstances in which balance sheet

financing may be the most appropriate policy choice, compared with direct

financing:

It’s horses for courses: direct financing – direct revenue

raising, for that matter – is the best way to do things, if you want to be able

to do things with a minimum of complexity around the arrangements and when you

have a clear view about what you want to achieve, how are you going to achieve

it and you have an understanding of the risks that are attached to that. … Where

you would think about something like equity is in an environment where, let’s

say, there is a business undertaking to be run. There is something that is

meant to endure and to transact in the economy more broadly, and you wish risk

to be distributed and managed in a different way over a long period. You would

do that through some other entity, and you would give that entity equity so

that it was set up in a particular way. It might have a board and some other

enabling documents and expectations around it, and it would be given equity,

which would give it the ability to pursue its objectives and make decisions in

its own right yet still contribute to the government’s overall intention in

that particular case. When you’re going down that path, you’ve made a different

judgement about how best to achieve an outcome, who should carry risk, where

risk is best managed and where, therefore, decision-making is best managed. [Page

4]

The case of the NRFC appears to be broadly consistent with

such a rationale.

Nonetheless, it is doubtful whether most Budget observers

could easily assess the risk exposure to uncertain returns across the $15

billion NRFC, $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund, $20 billion

Rewiring the Nation fund, $240 billion Future Fund (including subsidiary funds)

and other Australian Government equity investments – in aggregate and

individually. It is currently very difficult – if not technically impossible – to

scrutinise and form evidence-based opinions on such investments. The PBO’s

Dr Helgeby continued:

[Although balance sheet financing is not off-budget

financing,] that’s not to say that information can’t be presented in more

accessible and meaningful ways… In the case of balance sheet financing, the

impact of the policies will be reflected in the balance sheet and the budget

forecasts and actuals, but only as part of large totals, so the amounts [for

specific entities or initiatives] can be obscured. Estimated costs of new

policies are recorded in detail in the measures document, Budget Paper No. 2,

but normally only in terms of cash flows rather than stocks. This means that, unless

further information is made available, parliament would find it difficult to

fully assess the financial impact of policies such as loans, equity injections

and guarantees. … In summary, while straightforward decisions may not need

complicated information to explain them, complex arrangements such as those

that involve equity, loans or guarantees need other information to make them

readily understandable. …

At the moment, someone who is trying to get their head

around that … would have to piece things together … from the relevant

portfolio’s annual report, the portfolio budget statement and the budget papers

themselves. Often in the case of a government business entity you also have

to piece it together from the corporate plan or the other forward

looking documents of that entity itself. That, to be honest, makes it pretty

hard. It’s not that the information doesn’t exist; it’s that the information is

not put together in a way that helps people trying to understand these things.

[Pages 1–2, emphasis added]

Though based on outdated information about the timing of

equity injections, the PBO’s

election commitment costing for the NRF remains a valuable illustration of

the complexity involved in trying to forecast the fiscal impact of this type of

investment – even when ignoring the possibility of unforeseen investment losses

and revaluations.

Other relevant questions include the transparency of

potential debt interest repayments on the initial equity injections if NRFC

revenue expectations are not realised, and the potential inflationary impacts

of such a large injection into the economy, given that equity injections are not

captured in typical headline spending metrics like the UCB surplus or deficit.

The Final

Report of the JCPAA inquiry into alternative finance mechanisms, published

March 2022, recommended a number of reforms to improve Budget transparency

around use of the balance sheet, based on PBO proposals. The Budget

Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1 October 2022–23 stated that:

‘The Government is committed to improving transparency provided around the use

of the balance sheet’ (page 98), which may foreshadow an intention to implement

these reforms, or something similar. This will be something to watch in future Budgets.

Statement of Compatibility

with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[36]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing this Digest, the Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights had not yet considered the Bill.

Key issues and provisions

This section of the Digest explores key clauses in the

Bill and the issues they raise – particularly the breadth of discretion afforded

to current and future governments to determine the focus and practice of NRFC

investments through legislative instruments.

Establishment of the NRFC

Clause 11 establishes the NRFC and specifies that

the NRFC is a body corporate, and a corporate Commonwealth entity (CCE) for the

purposes of the PGPA Act. As discussed above, the establishment of the

NRFC as a statutory, Budget-funded CCE for the purposes of the PGPA Act

is consistent with Finance guidance and with the use of the CCE form for other

Commonwealth finance corporations, such as Export

Finance Australia (EFA), the National

Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC) and the Northern

Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF).

Main functions of the NRFC

Clause 3 states that the purpose of the NRFC is to

‘facilitate increased flows of finance into priority areas of the Australian

economy’.

The main functions of the NRFC are the investment

functions listed in clause 63, which enables the

NRFC and its subsidiaries[37]

to:

- provide

financial accommodation to constitutional corporations, the states

and territories, or individuals or other entities, and

- acquire

equity interests in entities.

The italicised terms are defined in clause 5 and

discussed in detail below.

Clause 12 includes the following ancillary

functions:

- to

liaise with relevant persons and bodies, including other Commonwealth entities

and state and territory governments, for the purposes of facilitating the

investment functions

- any

other functions conferred on the NRFC by this Act or any other Commonwealth law

and

- to

do anything incidental or conducive to the performance of the above functions.

No

definition of ‘Priority areas of the Australian economy’

The Bill and the Explanatory Memorandum do not define the

‘priority areas’ of the economy. The Bill’s ‘Definitions’ section, clause 5,

in turn refers to clause 6, which provides that priority areas of the

Australian economy will be declared by the Ministers in a legislative

instrument tabled in the Parliament and subject to disallowance. The Minister’s

second reading speech does identify priority areas[38];

however, as noted earlier, this list could be considered indicative and subject

to change.

The Explanatory Memorandum states:

Declaring the priority areas in a legislative instrument

allows for timely changes to the Corporation’s investment focus in the event

priority areas change, for example because of significant technological or

other unforeseen developments that require immediate or prompt changes to the

Corporation’s investment focus.[39]

Examples of potential circumstances requiring ‘immediate

or prompt changes’ are not provided.

This mechanism gives the Ministers and the Government

considerable latitude in the definition and selection of ‘priority’ areas of

the economy. Notwithstanding Government commentary to date and the announced 7

priority areas, nothing in the Bill requires future priority areas to relate to

manufacturing, technology, ‘reconstruction’ or even industry.

As the declaration is in the form of a disallowable

legislative instrument, the Parliament will have an opportunity for its views

to influence the selection of priority areas, however:

- Disallowance

motions may only disallow instruments or parts of instruments. They may not

amend them.[40]

- The

Constitution

provides that when questions arising in the Senate result in a tied vote, they

are resolved in the negative (they fail to pass).[41]

This practically means that the number of votes that the Government needs to

prevent disallowance of a legislative instrument in the Senate is one less than

the number of votes it needs to pass a Bill.[42]

- The

Legislation Act

2003 contains a prohibition against remaking disallowed legislative

instruments that are the ‘same in substance’ as previously disallowed

provisions (section

48). However, previous Parliaments have had some difficulty enforcing this

restriction.[43]

The NRFC’s

investment functions in detail

This section outlines the investment functions permitted

by the Bill, which are categorised as the provision of financial

accommodations, or the acquisition of equity interests. (Note that Clause 71

provides that the Ministers may, by legislative instrument, give the Board

directions about the performance of the NRFC’s investment functions, and

must give at least one such direction. The directions together constitute the

Investment Mandate,[44]

discussed further below.)

1. Financial

accommodations

Subclause 63(1) provides that the NRFC’s investment

functions include providing financial accommodation to eligible

recipients. Clause 5 explains that a financial accommodation can include

a loan, a letter of credit, a purchase of bonds or other debt securities, a

guarantee or ‘another form’ of accommodation, but excludes equity interests

(see below) and monetary grants equivalent to gifts.

The latter exclusion would appear to restrict the NRFC

from giving grants to states and territories with no expectation of repayment,

even if its payments to the states and territories are via the mechanism of a

grant of financial assistance for administrative reasons – see further below.

As noted above, a financial accommodation to an

entity other than a constitutional corporation or state or territory must

support a constitutionally-supported activity – explained further below.

Later in the Bill, clause 71 provides that the

Investment Mandate may define ‘the types of financial accommodation’ the NRFC

may provide to each class of recipient. This opens the door for permission to

use as-yet-unspecified other types of financial accommodation. There is no requirement

in the Bill that additional types of financial accommodation be expected to return

a profit. In practice, the distinctions between investments, speculation and gifts

may become blurred – see the sections ‘Financial implications’ and ‘Prudential

constraints’.

2. The acquisition

of equity interests

Clause 5 defines equity interest to mean a

share in a company, or an interest in a trust, or an interest in a partnership,

or an interest specified in the rules (clause 92 provides for the

Ministers to make rules). An equity interest does not include an

interest that, under the rules, is taken not to be an equity interest for the

purposes of the Act.

Paragraph 63(1)(c) provides that the NRFC or a

subsidiary may acquire equity interests in entities if:

(i) any of the entity’s activities are in a

priority area of the Australian economy and

(ii) all of the entity’s activities are

constitutionally-supported activities.

The phrase ‘entity’s activities’ is not defined in the

Bill, nor is there any guidance on what it means for any activity to be in a

priority area of the Australian economy – such as whether that activity must be

a significant share of the entity’s activities overall. For example, acquisition

of shares in a bank whose customers included just one ‘priority area’ manufacturer

would appear to be permitted under a literal interpretation of subparagraph 63(1)(c)(i).

The meaning of ‘constitutionally-supported activities’ is

explained further below.

Mandatory reporting

Clause 82 provides that, every quarter, the

NRFC must publish on its website information about financial accommodations and

equity interests during the quarter, including the form, value, and place or

places where the main activities are carried out. The quarterly reports will

also include ‘such other information (if any) as is prescribed by the rules;

and … any other information the Corporation considers appropriate’.

Clause 84 provides that the annual

report prepared by the NRFC Board in compliance with section 46 of the PGPA

Act must:

(a) set out details of the realisation of any investments

of the Corporation in the period;

(b) set out

details of any procurement contracts to which the Corporation is party that

were in force at any time in the period and that had a value of more than:

(i) $80,000; or

(ii) if a higher amount is prescribed by the

rules—the higher amount;

(c) set out details of any amounts paid to the Corporation

under subsection 55(2) in the period;

(d) set out details of any amounts paid by the Corporation

under section 58 in the period;

(e) set out such other information (if any) as is

prescribed by the rules.

Clause 83 provides that the Ministers may

publish additional reports from the NRFC.

Based on the above, new

financial accommodations and equity interests will be reported quarterly,

whereas realisations of investments will be reported annually, unless they are

made public in the ad hoc reports provided for by clause 83. While this

mandatory reporting is positive for transparency, the timing difference for

reporting new investments versus realisations (and hence profits and losses)

does mean the NRFC could, in theory, realise substantial losses for many months

of a reporting year without this being disclosed publicly.

Provisions allow for commercial-in-confidence, national

security and sensitive financial intelligence information to be omitted from

reports.

Requirement that investments be ‘constitutionally supported’

Subclause 63(1) appears to be an attempt to ensure

the constitutional validity of the Bill, insofar as it limits NRFC investments

to situations where the recipient is:

- a constitutional

corporation (paragraph 63(1)(a)) or

- a state

or territory receiving a grant of financial assistance (paragraph 63(1)(d))

or

- any

other entity engaged in constitutionally-supported activities (paragraphs

63(1)(b)–(c)).

This is presumably necessary to ensure that the

Commonwealth has valid constitutional power to pass the Bill and implement the

provisions contained therein.

Under the Constitution,

the federal government is responsible for the matters allocated primarily in

sections 51 and 52 (although there are other relevant sections); otherwise the

states have jurisdiction. The ability to regulate constitutional corporations

is a specific head of power under section 51(xx) of the Constitution.

Since the High Court handed down its decision in the WorkChoices Case in

November 2006,[45]

the ‘corporations power’ under section 51(xx) has been interpreted broadly so

that, as long as a law is addressed to a ‘constitutional corporation’, the

Commonwealth can regulate any aspect of what that corporation does.[46]

Accordingly, for these entities, there is no need for the

Bill to include an extra requirement that the constitutional corporation’s

activities also be ‘constitutionally-supported activities.’ It is sufficient if

the recipient entity is a constitutional corporation under Australian law and

has been provided with financial accommodation.

In relation to financial accommodations to the states and territories:

in 2018, the Senate Scrutiny of Bills Committee expressed its concern at the

limited Parliamentary scrutiny afforded to grants to the states and territories

in the National

Housing Finance and Investment Corporation Bill 2018 (NHFIC Bill). As

section 96 of the Constitution

confers the power to make such grants and to determine their terms and

conditions on the Parliament rather than the Executive, the Committee

recommended that the Bill be amended to include high level guidance as to the

terms and conditions under which such financial assistance may be granted to

the states and territories,[47]

though the NHFIC Bill was not amended in this fashion. The same issue affects