Key points

- The Bill proposes to amend the A New Tax System (Family Assistance) Act 1999and the A New Tax System (Family Assistance) (Administration) Act 1999 to make a number of changes to the Child Care Subsidy.

- It proposes to increase the maximum child care subsidy rate and extend the subsidy to those with higher levels of income. It also extends the availability of subsidised childcare for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and provides for discounted fees for staff engaged as educators.

- The Bill includes changes to increase the transparency of child care fees, and to tighten financial scrutiny and fraud control measures.

- Schedule 4 includes potentially controversial primary legislative definitions of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child and an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person.

Introductory Info

Date introduced: 27 September 2022

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Education

Commencement: The main provisions in Schedules 1 to 4 commence on 1 July 2023. Schedules

5 and 6 commence on the later of 1 January 2023 and the day after Royal

Assent. The remaining provisions commence on the day after Royal Assent.

Purpose of

the Bill

The main purpose of the Family

Assistance Legislation Amendment (Cheaper Child Care) Bill 2022 (the Bill)

is to give effect to the promise made by the Australian Labor Party (Labor) in

the lead-up to the 2022 Federal election to make early childhood education and

care more affordable.[1]

The Bill seeks to amend the A New Tax System

(Family Assistance) Act 1999 (the FA Act) and the A New Tax

System (Family Assistance) (Administration) Act 1999 (the FA

Admin Act) to:

- increase

the rate of the Child Care Subsidy (CCS)

- raise

the family income threshold which determines eligibility for the CCS

- increase

transparency surrounding the operation of child care services

- increase

access to child care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

- improve

integrity within the sector

- allow

child care providers to offer discounted fees to staff engaged as educators,

without impacting the rate of the CCS

- introduce

minor amendments to the operation of the CCS in certain limited circumstances.

Structure

of the Bill

The Bill comprises eight Schedules:

- Schedule

1: contains the main amendments to the FA Act to impact the rate of child

care subsidy that families are entitled to receive

- Schedule

2: amends the FA Admin Act to increase the financial reporting

requirements of large providers, and to provide families with more information

about the child care services they access

- Schedule

3: amends the FA Act and the FA Admin Act to introduce a base

level of 36 subsidised hours of child care per fortnight for Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander children, regardless of activity levels

- Schedule

4: amends the FA Admin Act to introduce measures that are intended

to reduce fraud

- Schedule

5: amends the FA Act and the FA Admin Act to permit child

care providers to offer a discount on child care fees to staff engaged as

educators

- Schedules

6–8: make minor amendments to the FA Act and the FA Admin Act to

improve or clarify the operation of child care subsidies.

Background

Australian

Government funding for child care

The Australian Government provides child care fee

assistance to families and direct assistance to services. The main program is

the Child Care Subsidy (CCS), which commenced on 2 July 2018, replacing

the Child Care Benefit and Child Care Rebate. A supplementary payment was also

introduced at the same time, the Additional Child Care Subsidy (ACCS) which

provides additional assistance for children at risk of abuse or neglect,

families experiencing financial hardship, those transitioning from income

support to work, grandparent carers on income support, and some low‑income

families. The ACCS replaced a number of previous payments including Special

Child Care Benefit, Grandparent Child Care Benefit and the Jobs, Education and

Training Child Care Fee Assistance payment.[2]

The former Coalition Government introduced changes to CCS

through the Family

Assistance Legislation Amendment (Child Care Subsidy) Act 2021. This

Act removed the annual cap on the CCS and increased the rate of the CCS paid to

families with multiple children under six years of age who are eligible for the

CCS.[3]

In addition, the former Government introduced temporary

adjustments in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic. In April 2020, new

funding arrangements were announced.

The early childhood education and care relief package provided child care

fee-free for families during the coronavirus pandemic. The funding arrangements

were put into effect by way of a legislative instrument: the Child Care Subsidy

Amendment (Coronavirus Response Measures No. 2) Minister’s Rules 2020. The

Rules automatically ceased on 1 September 2020.

Committee

consideration

Senate

Education and Employment Legislation Committee

The Bill has been referred to the Senate

Education and Employment Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 16

November 2022. Details of the inquiry are at the home

page for the inquiry.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Coalition

The Opposition has criticised the Bill for failing to

address workforce or access issues. Shadow Minister for Early Childhood

Education, Angie Bell, said that ‘The Government clearly has no plans to

increase access, no plans to address educator’s concerns and no plans to

address rising fees’.[4]

Australian Greens

The Australian Greens (the Greens) have similarly raised

concerns over the child care workforce. Education spokeswoman, Senator Mehreen

Faruqi, reportedly said that the Bill does not go ‘anywhere near far enough’,

calling for both universal free child care and better conditions for educators.

Additionally, she called for the activity test to be scrapped and the changes

to child care to be brought forward to the beginning of 2023.[5]

Independents

Some independents, such as Member for Goldstein, Zoe

Daniel, have previously called for changes to the subsidies to be brought

forward.[6]

Position of

major interest groups

Australian Childcare Alliance (ACA) had previously

congratulated the new Prime Minister for adopting all of ACA’s policy

recommendations, ‘including equitable access to affordable early learning

services’. Despite this support, however, the ACA has raised concerns

regarding workforce pressures facing the sector.[7]

Since the Bill’s introduction, the ACA and Early Childhood

Australia (ECA) have welcomed changes which, they say, will improve access to

child care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. However, the ACA

has called for reform of the activity test so as to ensure fully accessible

child care.[8]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill:

Total costs of the measures included in this Bill are

expected to be around $4.5 billion over four years from 2022-23, taking into

account the savings that will be provided by the increased integrity measures

included in this Bill. Final costs of the measures included in this Bill are to

be agreed in the upcoming 2022-23 October Budget and will be reflected in the

relevant Budget statements.[9]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[10]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing the Parliamentary Joint Committee

on Human Rights had not reported on the Bill.

Key issues

and provisions

Increasing

the child care subsidy

CCS is characterised by the

following:

- subsidy

rates are based on an individual and their partner’s combined annual taxable

income

- the

amount subsidised varies depending on the type of child care service which is used

(for example, centre-based long day care, outside school hours care or family

day care)

- an

activity test determines the number of hours per fortnight a family is eligible

to receive CCS[11]

- whether

the individual or their partner has two or more children aged five years or under

using child care[12]

- a

maximum hourly amount payable via the subsidy is set by the Government (the

hourly rate cap) with families receiving a percentage of the lesser of this

rate or the actual fees charged based on their income.[13]

The payment is paid directly to providers to be delivered

to families in the form of a fee reduction.[14]

Child care services must meet certain conditions to be

approved to pass on the CSS, including requirements set by the Australian

Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority.[15]

Schedule 1 of the Bill raises the maximum rate of

the CCS from 85% to 90% of the fee charged (or the hourly fee cap, whichever is

the lesser). The rate will gradually reduce by one percentage point for every

$5,000 of family income above $80,000.[16]

The CCS rate would reach zero for families with an annual income of around

$530,000, an increase from the maximum family income of $356,756 currently in

place.[17]

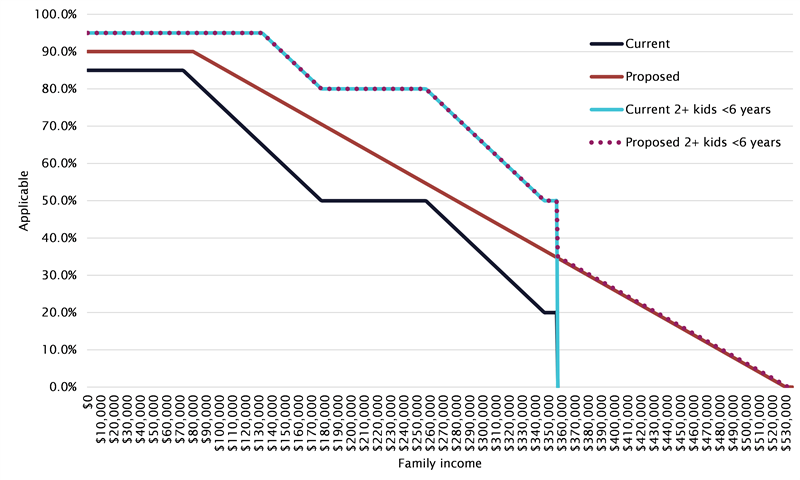

The projected effect of these changes can be seen in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 Child

Care Subsidy rate under the income test: % of fee or hourly rate cap

Source: Parliamentary Library estimates.

According to analysis by Ben Philips at the Australian National

University Centre for Social Research and Methods (based on Labor’s election

policy) the proposed changes would lower out‑of-pocket costs of child

care by an average of 34%; although they favour higher income child care

households, with ‘62 per cent of gains flowing to the top 40 per cent of child

care households but only 15 per cent to the bottom 40 per cent of child care

households’.[18]

Key provisions

The Bill amends the FA Act which contains, amongst

other things, the method statement and relevant formulae for calculating the

amount of CCS that is payable for sessions of care provided in respect of a

child.[19]

Currently clause 3 in Schedule 2 makes reference to

calculating CCS for a basic case whilst clause 3A in Schedule 2

sets out how to calculate CCS for other cases.

Amending

the definitions

Items 1–10 in Schedule 1 to the Bill insert new

definitions into section 3 of the FA Act and repeal others that will no

longer be relevant to the calculation of an amount of CCS. The new definitions

relate to relevant income thresholds and apply to the formulae for calculating

the amount of CCS in Schedule 2 of the FA Act. The amendments preserve

the two ways of calculating CCS but references to basic case become references

to base rate and references to other cases become references to other

rate in the relevant definitions.

In particular, proposed definitions of:

- fourth

income (other rate) threshold inserted by item 1

- lower

income (other rate) threshold inserted by item 3

- second

income (other rate) threshold inserted by item 5

- third

income (other rate) threshold inserted by item 7

- upper

income (other rate) threshold inserted by item 9

give effect to CCS rates for second and further children

in families that have more than one child under the age of six in child care.

Increasing

the base rate percentage

The applicable percentage of CCS that families receive

during the financial year is based on their estimated combined annual income. A

family’s CCS percentage is used in combination with the child care fees charged

to calculate the amount of subsidy per hour each family is entitled to receive

for their child's attendance at a session of care. This will be the applicable

percentage of the actual fee charged, or of the relevant hourly rate cap

(whichever is lower).

Item 11 amends the table of applicable percentages

for base rate CCS in subclause 3(1) in Schedule 2 of the FA Act by

increasing the maximum percentage from 85% to 90%. This means, by way of

example, that individuals earning equal to or less than the proposed lower

income (base rate) threshold of $80,000 (inserted by item 14) will now

be entitled to higher CCS rates.[20]

Amending

the base rate formula

Item 12 amends the base rate formula in subclause

3(2) of Schedule 2 of the FA Act. The effect of this amendment is that

for individuals earning more than the lower income (base rate) threshold

($80,000), but below the upper income (base rate) threshold ($530,000 inserted

by item 14), the applicable percentage will go down by 1% for

every $5,000 above the lower income (base rate) threshold they earn.

Amending

the other rate formula

Items 15–17 amend subclauses 3A(1)–(5) of Schedule

2 of the FA Act. The purpose of these amendments is to give effect to

rates of CCS that apply to families with more than one child under six years of

age in child care.[21]

The amendments operate so that an individual with one or

more children who meet the requirements of the term higher rate child

as set out in clause 3B of Schedule 2 of the FA Act can receive a higher

subsidy. [22]

Item 16 inserts proposed paragraph 3A(1)(c)

and a note into Schedule 2 of the FA Act the effect of which is to make

clear that, if the individual’s adjusted taxable income is equal to or above

the upper income (other rate) threshold, ($356,756 inserted by item

17) then the individual’s applicable percentage will be determined as usual

under clause 3 of Schedule 2—that is the base rate formula.

Further, proposed subclause 3A(2) (inserted by item

17) provides that if the individual’s applicable percentage will be higher

if it is determined under clause 3 (that is, the base rate formula) then it is

to be calculated using clause 3.

Item 17 sets out two new formulae for working out

an individual’s applicable percentage where there is a higher rate child.

First, proposed subclause 3A(4) is to be used if

the adjusted taxable income is above the lower income (other rate)

threshold (that is, $72,466) and below the second income (other

rate) threshold (that is, $177,466). The relevant formula operates so

that the individual’s applicable percentage for their higher rate child will be

the lower of either:

- 95%

or

- the

result of the following calculation

- subtract

the lower income (other rate) threshold from the individual’s adjusted taxable

income

- divide

that amount by $3,000 and

- subtract

the result from 115 and round to two decimal places.[23]

This has the effect of tapering the applicable percentages

down by 1 percent for every additional $3,000 over the lower income (other

rate) threshold the individual earns.[24]

Second, proposed subclause 3A(5) is to be used if

the adjusted taxable income is equal to or above the third income (other

rate) threshold (that is, $256,756) and below the fourth income

(other rate) threshold (that is, $346,756). The relevant formula

operates so that the individual’s applicable percentage is worked using the

following calculation:

- subtract

the third income (other rate) threshold from the individual’s adjusted taxable

income

- divide

that amount by $3,000 and

- subtract

the result from 80 and round to two decimal places.

This operates so that the applicable percentages taper

down by 1 percent for every additional $3,000 over the third income (other

rate) threshold the individual earns.

Item 25 repeals Part 2 of Schedule 2 of the FA

Admin Act. The previous Government’s changes established a two-phased

approach to determining which families continued to qualify for the higher rate

child payment. Phase 1, which came into effect in March 2022, included changes

providing that an individual is no longer eligible for the CCS via a fee

reduction where there has been no report from a provider indicating that a

session of care has been provided to a child for a period of at least 26 weeks.

This change effectively prevented families from claiming the higher rate of the

CCS by claiming the subsidy for an older child not actually using child care

services.[25]

Phase 2, which was due to come into effect in July 2023,

would have reduced the period families could continue to access the higher rate

of the CCS after their eldest child left care to 14 weeks. However, speaking in

relation to the Bill, Minister for Education, Jason Clare, said:

That measure is forecast to save $34 million over four years.

The problem is that the same measure is forecast to cost more than $89 million

to implement. That's almost three times what it was meant to save. That is an

expensive saving. That measure is therefore removed in this bill.[26]

Increased

provider reporting and publication of information

Part 1 of Schedule 2 to the Bill seeks to increase

the financial reporting obligations for large child care providers. The purpose

of this is for the Department to have greater visibility of the financial

viability of large providers and so to better anticipate situations such as the

collapse of ABC Learning in 2008.[27]

Currently, Division 4 of Part 8A of the FA Admin Act

provides for the Secretary to request information on financial viability from

large centre-based day care providers.[28]

If, on the basis of this information, the Secretary has concerns about the

financial viability of a provider they can engage someone to undertake an

independent audit of the provider.[29]

Items 1 repeals the existing definition of large

centre-based day care provider in subsection 3(1) of the FA Admin

Act. Items 2 to 4 substitute a new definition of large child

care provider to include those providing other services, such as family

day care and outside school hours care. Under the proposed amendments, all

providers (including related providers) who operate, or propose to operate 25

or more approved child care services will be subject to this requirement [proposed

subsection 4A(1)].

In addition, Item 10 introduces a requirement for

large providers to provide financial information as prescribed by the

Minister’s rules [proposed section 203BA], while Item 11 extends

the audit provision to cover the information received in these reports.

Part 2 of Schedule 2 provides for the Secretary

to publish electronically a range of information about child care providers,

including a list of the services provided, the fees charged and information on

fee increases [proposed section 162B].

According to the Explanatory Memorandum:

It is envisioned that this information may be published on www.startingblocks.gov.au, which

is administered by the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality

Authority (ACECQA) on behalf of the Commonwealth and state and territory

governments to make it easier for parents to make informed decisions about what

child care services to use.[30]

Increasing

access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

Schedule 3 to the Bill proposes to increase the

access to child care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children through

modifying the activity test requirements for receiving the CCS in the FA

Act.

Activity

test

The number of hours of subsidised child care is generally based

on the number of hours both members of a couple (or a single parent) are

participating in recognised activities such as paid work or education.[31]

Clause 12 of Schedule 2 of the FA Act (as set out below)

specifies the entitlement to CCS, depending on the number of hours of recognised

activity in the fortnight. For example, where more than 16 but less than 48

hours are performed, the claimant is entitled to up to 72 hours of subsidised

care for that fortnight.

| Recognised activity result |

| Item |

If an individual engages in this many hours of recognised

activity in the CCS fortnight: |

The result is: |

| 1 |

fewer than 8 |

0 |

| 2 |

at least 8 and no more than 16 |

36 |

| 3 |

more than 16 and no more than 48 |

72 |

| 4 |

more than 48 |

100 |

Exceptions are made for children in special circumstances,

such as where the child is at risk of abuse or neglect [existing sections

85CA–85CF], or the claimant is experiencing temporary financial hardship [existing

sections 85CG–85CH], and in these cases a higher

rate of subsidy (Additional Child Care Subsidy (ACCS)) also applies.

Benefits of

quality early learning on development

Data from the Australian Early Development Census suggests

that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are considerably more

likely to be developmentally vulnerable than other children in their first year

of schooling. For example, in the 2021 Census, 42.3% of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander children were considered vulnerable on at least one domain,

compared to 22.0% overall, while 26.5% were vulnerable on 2 or more domains

compared to 11.4% overall.[32]

It is generally acknowledged that children from

disadvantaged backgrounds benefit developmentally from participating in

high-quality childcare and early learning programs, particularly in the years

immediately before starting school.[33]

The intention of this measure is to increase the number of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children attending child care and hence

improve their development prior to attending school. However, Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander children are already enrolled in early childhood

education (ECE) programs at a higher level than for all children, but their

attendance rate is lower.[34]

This suggests that increased access on its own may not result in significantly

higher attendance. There is also less availability of child care services in

rural and remote locations, as well as in socially disadvantaged areas, both of

which are likely to impact access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

children.[35]

Therefore this measure’s impact may be dependent on the success of other

measures to boost access and attendance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander children.[36]

New

definitions

Item 3 in Schedule 3 to the Bill inserts proposed

clause 15A in Part 5 of Schedule 2 on the FA Act (which deals with

the activity test). Proposed subclause 15A(1) specifies that the Aboriginal

or Torres Strait Islander child result (for the purposes of the

activity test) is 36. This means that at least 36 hours of CCS a fortnight is

available for those caring for an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child,

regardless of activity levels. Those engaging in more than 16 hours of

recognised activities would be eligible for additional hours of CCS on the same

basis as for non-Indigenous children.

Aboriginal

or Torres Strait Islander person

New definitions of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait

Islander child and an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person

are also included in proposed clause 15A. This appears to be the first

use of these definitions in Commonwealth primary legislation.[37]

Commonwealth legislation has in the recent past defined an

‘Aboriginal person’ as ‘a person of the Aboriginal race of Australia’ and a ‘Torres

Strait Islander’ as ‘a descendant of an indigenous inhabitant of the Torres

Strait Islands’.[38]

These race-based definitions were introduced during the 1970s in order to clearly

connect legislation with the Commonwealth’s ‘race power’ in section 51(xxvi) of

the Constitution.

However, in practice and in administration, Commonwealth programs define an Aboriginal

or Torres Strait Islander person as one who:

- is

of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent and

- identifies

as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person and

- is

accepted as such by the community in which they live or have lived.[39]

This three part definition has also been accepted as ‘the

conventional meaning’ of ‘Australian Aboriginal’ [40]

and has been usually, though not exclusively, used by the courts as the

‘ordinary definition’ in many cases, including Mabo

v Queensland (No. 2).[41]

It is also used in some state legislation, such as the Aboriginal

Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) [section 4].

The definition proposed in the Bill changes the second and

third parts of the ordinary three-part definition to:

- identifies

as a person of that descent and

- is

accepted by the community in which the person lives as being of that descent.

This definition is apparently based on the definition of

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander student made in section 16 of the Australian Education

Regulation 2013.[42]

That instrument’s Explanatory

Statement does not explain the change from previous legislative or

administrative definitions.[43]

Aboriginal

or Torres Strait Islander child

The definition of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait

Islander child replicates those three criteria. However, it has been

expanded to include two alternate criteria:

- the

child is biologically related to an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person

[proposed paragraph 15A(3)(b)] or

- the

child is a member of a class prescribed by the Minister’s rules [proposed paragraph

15A(3)(c)].

Effect of

the new definitions

There is no rationale provided in the Explanatory

Memorandum for these changes to the three- part definition. The ‘biologically

related’ alternate criteria is explained as ‘enabl[ing] the inclusion of

children who may be too young to have formed a sense of cultural identity’

while the ability to prescribe a class in the Minister’s rules is explained as

‘provid[ing] some flexibility to expand the definition in case it is identified

as being too narrow’.[44]

Given the precedent set in the case of Shaw v Wolf in which Justice

Merkel found that descent did not need to be proved ‘according to any strict legal

standard’ it is unclear how the courts would interpret new provisions relating

to descent. Justice Merkel stated:

That some descent may be an essential legal criterion

required by the definition in the Act is be accepted. However in truth, the

notion of "some" descent is a technical rather than a real criterion

for identity, which after all in this day and age, is accepted as a social,

rather than a genetic, construct.[45]

The new definitions potentially create a number of issues,

for example:

- It

may be difficult for the communities in which people currently live to assess

whether someone is of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent, for

example, where someone has moved away from their birth community. Other uses of

this community-based definition usually add ‘or has lived’, so as to remove any

requirement to repeatedly prove Indigenous status in one’s current residential

community.[46]

- ‘Descent’

may be sensitive or difficult to prove for Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander

people or their children who were removed from their families, or who lack

birth certificates.

- It

is unclear whether a non-biologically-related child legally adopted by an

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander parent would qualify.

- The

introduction of a reference to being ‘biologically related’ as an alternate,

sole criteria potentially makes the subsidy accessible to people who have no

connection with an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander identity or community,

but have a distant Indigenous ancestor (identified, for example, through

ancestry DNA test kits).

- The

repeated emphasis on descent and biological relationship potentially limits the

right of self‑identification under Article 33 of the United

Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP),

including the right not to identify as Indigenous.

Prominent Aboriginal organisations and legal academics

have formerly stated that courts have previously over-emphasised ‘descent’, in

ways which do not recognise Indigenous kinship relations and rights of

self-determination.[47]

This new definition may exacerbate these concerns.

Dealing

with serious non-compliance

The CCS scheme has been the target of fraud, with

providers signing up children who do not actually attend the service, but for

which the provider claims the CCS.[48]

It is anticipated that the increased subsidies provided for in the Bill will

increase the incentive for fraud.

Schedule 4 consists of three parts each of which amends

the FA Admin Act:

- Part

1 introduces new requirements to ensure providers have in place

arrangements to ensure those with management and control of the provider comply

with the family assistance law.

- Part

2 requires the electronic payment of gap fees.

- Part

3 provides for the information required to be included in the weekly

session reports to be specified in the Secretary’s Rules, rather than leaving

the requirements to be specified administratively.

Under existing section 194C (for providers) and section 194D

(for services) in Part 8 of the FA Admin Act (which deals with approval

of child care services), the eligibility rules require those with management

and control of the provider or service to be ‘a fit and proper person to be

involved in the administration of CCS and ACCS’. Subsection 194E(1) then

requires the Secretary to consider if someone is a fit and proper person,

having regard to, among other things ‘the arrangements the person has: to

ensure the person complies with the family assistance law [subparagraph

194E(1)(g)(i)]; and to ensure anyone the person is responsible for managing

complies with the family assistance law’ [subparagraph 194E(1)(g)(ii)].

Item 3 in Part 1 of Schedule 4 repeals

this requirement. Instead items 1 and 2 insert proposed paragraphs

194C(da) and 194D(da) respectively to place the onus on the provider to

have in place arrangements to ensure that those with management and control of

the provider or service comply with family assistance law. The Government considers

that placing this obligation directly in the eligibility rules, rather than

retaining it as a consideration in the fit and proper person test, strengthens

the requirement.[49]

Under the changes proposed in Part 2 providers will

be obliged to collect gap fees by electronic payment (with exceptions for

special circumstances). This is intended to provide an electronic record of payments

as in many of the fraud cases identified no gap fees had been paid.[50]

Discount on

fees to staff engaged as educators

The Bill would also legislate to allow providers to offer

discounts to their educators. The Explanatory Memorandum indicates that the

‘objective of this measure is to reduce staff shortage in the [early childhood

education and care] ECEC sector by attracting and retaining existing educators,

particularly those with young children’.[51]

Although this has already been implemented on a short-term

basis through the Minister’s Rule made under subsection 201B(1A) of the FA

Admin Act, it is considered that these short-term changes are better

legislated, and that this provides an opportunity to clarify the fringe

benefits tax implications of the measure.[52]

Schedule 5 proposes to amend the definition of the

‘hourly session fee’ in subclause 2(2) of Schedule 2 of the FA Act, to

ensure the amount reflects what the educator, prior to any discount, would be

liable to pay. The effect of this is that educators eligible for a discount on

their own child care costs will not have their CCS payments reduced. The Bill

would also insert a note that would highlight that the allowable discount would

not attract fringe benefits tax in the circumstances set out in subsection

47(2) of the Fringe

Benefits Tax Assessment Act 1986 (very basically, if the benefit

provided to a current employee is child care provided in a child care facility

located on the business premises of the employer).[53]

The Bill also inserts proposed section 201BA into

the FA Admin Act setting out the arrangements for these discounts,

including prohibiting the ‘permissible educator discount’ from being more than

95% of the pre-discount fee for a week.

Other provisions

Schedules 6 to 8 propose technical amendments to

improve clarity and flexibility in the event of certain exceptional

circumstances.