Introductory Info

Date introduced: 25 August 2021

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Indigenous Australians

Commencement: See details under the subheading ‘Commencement details’ in this Digest.

The Bills Digest at a glance

The Aboriginal

Land Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment (Economic Empowerment) Bill 2021

(the Bill) makes significant and far-reaching reforms to the Aboriginal Land

Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (the Act). The Bill contains four

Schedules, of which the amendments made in the first Schedule are the most

significant.

Schedule 1’s amendments create a Northern Territory

Aboriginal Investment Corporation (NTAIC), lay out the procedure for electing

and appointing its board and guiding its investments, and put in place

transitional arrangements. Approximately half ($680 million) of the current

accumulated balance of the Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) ($1.3 billion)

will be transferred to the NTAIC over three years. This will allow the

transferred funds to potentially achieve much greater results than management

under the conservative requirements of the Public Governance, Performance

and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) for investment of special

accounts, although the NTAIC must attend to several, potentially conflicting

investment goals. The NTAIC will be managed by a board with a majority elected

by the Aboriginal Land Councils of the Northern Territory, and its investments

will be actively directed towards Indigenous economic development. The

remaining balance and ongoing operation of the ABA will still be controlled by

the Minister for Indigenous Australians. The Bill abolishes the Advisory

Council which currently advises the Minister on ABA spending.

Schedule 2 implements several amendments recommended by

the Aboriginal Land Commissioner’s 2013 Review of Part IV of the Aboriginal

Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 concerning mining activity under

the Act.[1]

These amendments update the Act to reflect Northern Territory legislation and

developments in mining (for example, concerning geothermal energy), clarify and

change aspects of the approval process (including meeting requirements with

Traditional Owners), clarify the process for dealing with relatively low impact

mining for ‘extractive minerals’ (clay, gravel, sand, et cetera), and change

parts of the ministerial approval process by removing delegation of some

Commonwealth ministerial approvals from the Northern Territory mining minister

and removing the requirement for Commonwealth ministerial approval for some

mining projects.

Schedule 3 makes changes to land administration and

control processes including those for township leases, delegation of land

council functions, land in escrow, ministerial approvals, and control over

access to Aboriginal land. These alter contentious amendments first made in

2006 and 2007 by the Howard Government. These changes act on long-standing Land

Council concerns.

Schedule 4 aligns the statutory requirements for payments

into and out of the ABA with current practice, reflecting that payments are

currently made based on estimates of mining royalties rather than final

figures, meaning that overpayments may need to be recouped or underpayments

supplemented when final figures become available.

This Bill offers a Solomonic resolution to the Aboriginal

Land Councils’ long-standing (particularly since 2006) concerns about the use

of the Aboriginals Benefit Account by the Commonwealth Government, by dividing

the account’s accumulated balance in half. One half will now be invested

through the NTAIC, while the Commonwealth will arguably increase its

expenditure powers (and maintain the current investment strategy) over the

other half. The Land Councils have expressed satisfaction with this compromise.

Purpose and Structure of the

Bill

The purpose of the Aboriginal

Land Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment (Economic Empowerment) Bill 2021

(the Bill) is to amend the Aboriginal Land

Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (the Act) in four areas, covered

by four Schedules:

-

Schedule 1 will establish the Northern Territory

Aboriginal Investment Corporation (NTAIC) as a new Aboriginal-controlled corporate

Commonwealth entity to strategically invest in Aboriginal businesses and

commercial projects and make other payments to or for the benefit of Aboriginal

peoples in the NT

-

Schedule 2 will amend the exploration and mining

provisions of the Act in order to clarify and streamline a number of approval

processes

-

Schedule 3 will amend and clarify land administration

provisions, including on township leases, access to Aboriginal land, land under

escrow and other matters

-

Schedule 4 will align payments from the Aboriginals

Benefit Account (ABA) with the Commonwealth’s financial framework and the

timing of mineral royalties payments from the Northern Territory (NT).[2]

Commencement details

The substantive amendments relating to the NTAIC contained

in Part 1 of Schedule 1 commence on Proclamation or 12 months

after Royal Assent, whichever is sooner. The majority of the remaining

amendments commence on the day after Royal Assent, which the exception of

amendments relating to township land and increases to penalties for entering or

remaining on Aboriginal land (Part 4 of Schedule 3) which commence 12

months after Royal Assent.

Background

The Act sets out a scheme for the claiming, granting,

control and management of Aboriginal land by traditional Aboriginal owners in

the NT. The Fraser Government passed the Act after the dismissal of the Whitlam

Government meant the original Aboriginal Land (Northern Territory) Bill 1975

lapsed.[3]

Fraser’s Act and Whitlam’s Bill both responded to Justice Woodward’s 1973–1974

Aboriginal Land Rights Commission report,[4]

which was accepted in principle by both major parties.[5] While there were some

significant differences between the two pieces of legislation, the Act

ultimately passed with bipartisan support.[6]

The Act provides for title to land to be granted to a Land

Trust on behalf of the traditional owners.[7]

Title is inalienable and equivalent to freehold title but is held communally,

reflecting the nature of Aboriginal land ownership. The Act also provides for

Land Councils, who represent traditional owners and negotiate with mining

proponents and land developers on their behalf.[8]

It provides that royalty equivalent payments from mining on Aboriginal land are

paid into an Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA).[9]

The ABA funds Land Councils, compensatory payments to traditional owners, and

grants after payment of a Mining Withholding Tax (MWT) (introduced in 1979).[10] The ABA itself

predates the Act, being originally enacted as a beneficial trust fund by then

Minister for Territories Paul Hasluck in 1952, as reparation for allowing

mining on what were then Aboriginal reserves.[11]

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill states:

… [a]mendments to the Land Rights Act are not common.

Aboriginal stakeholders in the NT have strong voices through their Land

Councils (the NLC [Northern Land Council], CLC [Central Land Council], ALC

[Anindilyakwa Land Council] and TLC [Tiwi Land Council]) and the Commonwealth

has committed to only amend the Land Rights Act with their support.[12]

Despite this statement, the Act has been amended many

times – sometimes simply to add additional land claims, which may require

parliamentary action,[13]

but frequently for more fundamental amendments. On many occasions (particularly

in 2006 and 2007, see below) it has been amended in ways which the Land

Councils have not supported. Many key features of the Bill are best understood

as rollbacks of, or compromises over, past amendments to which the Land

Councils objected at the time. Other proposed amendments are the results of

reviews of the Act which have not been acted upon to date.

Past amendments, reports and reviews

Past amendments, policies, reports and reviews to which

this Bill directly or indirectly responds include:

-

the 1984 Report on the Review of the Aboriginals Benefit Trust

Account (and related financial matters) in the Northern Territory land rights

legislation by Professor Jon Altman,[14]

which recommended, among other matters, that, over time, some functions of the

ABA should be transitioned to a statutory body with its grant-making function

controlled by an Aboriginal board, and the range of permitted investments of

the ABA’s balance should be widened. This original recommendation is alluded to

in the NIAA’s fact sheet on the proposed NTAIC.[15]

-

the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment Act

(No 3) 1987,[16]

which, among other matters, mandated conjoined applications for exploration and

mining in Aboriginal land (that is, consent to an exploration licence also

acted as consent for a mining licence) and other changes to the mining approval

process.[17]

-

ANAO Report 22 of 2002–03, Northern Territory Land Councils

and the Aboriginals Benefit Account,[18]

and the 2008 Department of Finance and Deregulation, Office of Evaluation and

Audit (Indigenous Programs) report Performance Audit of the Aboriginals

Benefit Account (the OEA report)[19]

both recommended, among other matters, that the managing entity (in 2002 this

was the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) and in 2008

this was the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous

Affairs (FaHCSIA)) pursue a more active investment strategy for the funds

accumulated in the ABA.[20]

At the time the OEA report was critical of FaHSCIA’s

administration of payments under section 64(4) of the Act, finding that

FaHSCIA’s assessment of grant applications was ‘cursory’ and that the

Aboriginals Benefit Account Advisory Committee (ABAAC) was not provided with

sufficient information by the Department to enable it to effectively contribute

to decisions.[21]

Neither recommendation for more active investment management was acted upon, in

part because of the difficulty of reconciling an investment strategy with the

requirements of the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (the

precursor to the current PGPA Act).[22]

-

the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Amendment

Act 2005,[23]

which abolished ATSIC. ATSIC had been the lead agency administering the ABA.

After its abolition, Ministers, through the relevant department, took a more

active role in managing the ABA.

-

the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment Act

2006 (the 2006 Amendments),[24]

among other matters:

- created the legislative structure for township leasing by an

entity (since administered by the Commonwealth’s Executive Director of Township

Leasing (EDTL) under Part IIA of the Act, which was inserted by the Aboriginal Land

Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment (Township Leasing) Act 2007)

- provided for township leasing expenses and leases to be paid out

of the ABA (rather than the leasee, for example, the NT or Commonwealth

governments)

- enabled Land Councils to delegate some of their functions to

corporations formed under the Corporations

(Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI corporations)

-

changed a number of sections relating to mining approvals

processes in Part IV of the Act,

-

enabled the Minister to designate an amount of the ABA to be

retained and invested rather than distributed (the ‘investment amount’, section

62A)

- changed Land Councils’ income from the ABA from a statutory 40

per cent of mining royalty equivalents (potentially plus additional funds, see

below) to an amount determined by the Minister upon receiving budget estimates

prepared by the Land Councils

- removed the ability for the Minister to direct that additional

funds from the ABA be directed to Land Councils to meet their administrative

costs (former subsection 64(8) of the Act, instead such amounts would fall

under the broader amount determined by the Minister mentioned above)

- enabled the Minister to appoint some members of the ABAAC

(formerly a body entirely composed of Land Council appointees, with the

exception of the Chair) and

-

provided for a review of the amendments to Part IV (mining) to be

carried out five years after the amendments had commenced.

Several of these provisions, particularly those which paid

what would otherwise be normal government budget expenses (rent of land and

buildings) out of the ABA, and made Land Council budgets significantly more

dependent on ministerial approval, were strongly objected to by Land Councils

and others at the time. For further details of the 2006 Amendments, see its

Explanatory Memorandum,[25]

Bills Digest[26]

and Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs Legislation Committee

Inquiry Report.[27]

-

the Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and

Other Legislation Amendment (Northern Territory National Emergency Response and

Other Measures) Act 2007,[28]

which inserted section 74AA into the Act, as part of a suite of measures (in

Schedule 4 of that Act) that significantly increased governmental and private

non-Aboriginal access to Aboriginal land.[29]

-

in 2012, then Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services,

and Indigenous Affairs, Jenny Macklin, commissioned the Aboriginal Land

Commissioner, JR Mansfield, to carry out the review of Part IV of the Act as

legislated in the 2006 Amendments. The resulting Report on review of Part IV

of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (the 2013

Review) was completed in March 2013 and subsequently tabled in Parliament.[30] According to the

Explanatory Memorandum, the recommendations have since been the subject of a

Working Group consisting of the Commonwealth, NT Government, and the Land

Councils, which also carried out further consultations with mining industry

peak bodies.[31]

Many provisions of Schedule 2 of the Bill implement or respond to

recommendations of that review.

-

in 2013, the incoming Coalition Government committed to

supporting the Act,[32]

and to ‘resolve outstanding Aboriginal land claims in the Northern Territory

and to work with Indigenous land owners to ensure their land rights deliver the

economic opportunities that should come from owning your own land.’[33]

Manifestations of this commitment include the successful

resolution of the long-standing Kenbi land claim[34] and resolved land claims in

Kakadu, Urapanga, Anthony Lagoon,[35]

and Ammaroo,[36]

although former Minister for Indigenous Affairs, Nigel Scullion, also refused

to act upon a number of significant outstanding claims.[37] After initial suspicion of

the ‘deliver economic opportunities’ part of the Coalition Government’s

commitment,[38]

the Land Councils appear to have arrived at a rapprochement with Minister Wyatt[39] and to have

embraced the economic development possibilities offered by this Bill through

the NTAIC.

-

In 2019–20, the Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia

held an Inquiry into the Opportunities and Challenges of the Engagement of

Traditional Owners in the Economic Development of Northern Australia.[40] This Committee

heard evidence about the potential uses of the ABA to promote economic

development for traditional owners.[41]

The Inquiry, and consequently its report, have been suspended due to the

COVID-19 pandemic.

Committee consideration

On 21 October 2021, after being passed by the House of

Representatives, the Bill was referred by the Selection of Bills Committee to

the Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration (Legislation

Committee) for inquiry

and report by 25 November 2021.[42]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

considered the Bill in Scrutiny Digest 15 of 2021.[43] The Committee raised concerns

about proposed provisions which create no-invalidity clauses, use delegated

legislation, non-reviewable instruments, some reports not being tabled in

Parliament, and standing appropriations in the Bill, and requested further

advice from the Minister on these proposed sections.

The Committee noted that proposed subsection 65BH(3)

(item 6 of Schedule 1 of the Bill) and proposed subsection

12D(7) (item 25 of Schedule 3 of the Bill) state that a

failure to follow the procedural requirements set out in the Bill (to seek

Ministerial approval of investments over $100 million, and to seek

traditional owner approval of agreements over land held in escrow) does not

invalidate the transaction or agreement concerned. The Committee expressed

concern that such ‘no invalidity’ clauses may impact on the practical efficacy

of judicial review.[44]

The Committee noted that a number of proposed subsections

allow significant matters regarding the financial conduct of the NTAIC on

loans, investments, borrowings and loan guarantees, to be varied by the ‘NTAIC

rules’, a delegated legislative instrument to be made by the Minister (under proposed

section 65JE at item 6 of Schedule 1 of the Bill). The

Committee expressed concern at the use of delegated legislation for significant

details and asked the Minister for more advice on whether this was necessary

and appropriate, and whether the Bill could be amended to include ‘at least high-level

guidance’ on these matters in the primary legislation.[45]

The Committee noted while that the strategic investment

plan of the NTAIC prepared under proposed section 65C is to be tabled in

parliament, it is not a legislative instrument and therefore not subject to

parliamentary oversight. The Committee asked for the Minister’s advice on

whether the plan could be made a legislative instrument.[46]

The Committee also noted that as part of the transitional

measures, the Minister may request the Board of the NTAIC to prepare a progress

report on the strategic investment plan (item 19 of Schedule 1).

While the Minister may publish such a report on the internet (subitem

19(4) of Schedule 1), they are under no obligation to do so. The

Committee asked for the Minister’s advice on whether the progress report could

be tabled in Parliament and also be required, rather than permitted, to be

published online.[47]

The Committee noted that many parts of the procedure for a

body becoming an approved entity to hold a township lease under proposed

section 3AA (item 4 of Schedule 3 of the Bill) will be made

by a legislative instrument. The Committee asked for the Minister’s advice on

why this was necessary and appropriate, and whether the legislation could be

amended to provide at least high-level guidance in the primary legislation.[48]

The Minister responded to the committee in a letter dated

29 September 2021, which was published

by the Committee, along with its

response to the Minister, on 21 October 2021. The Minister stated (in

summary) that:

-

no-invalidity clauses were necessary and appropriate to protect

the rights of, and provide business certainty to, entities transacting with the

NTAIC and stakeholders negotiating with Land Councils

-

details of the NTAIC’s business functions are to be administered

through legislative instruments in order to provide flexibility for the NTAIC

to address investment-related risks and other commercial matters in a timely

way

-

the Strategic Investment Plan is administrative rather than

legislative in nature and hence is not required to be an instrument, and making

it subject to Parliamentary approval would weaken Aboriginal peoples’ and

organisations’ right to self-determination

-

the progress reports on the Strategic Investment Plan are likely

to be largely operational in nature, may contain commercially sensitive

material, and will in any case be followed by tabled plans and reports and

-

the township lease approval process already contains a number of

conditions that must be satisfied before the Minister issues an instrument and,

given that the conditions pertaining to particular townships cannot be

predicted in advance, the additional flexibility granted by a legislative

instrument is warranted.[49]

In its response to the Minister, the Committee largely

reiterated its original concerns, requested some additions to the Explanatory

Memorandum to take account of information supplied by the Minister, and drew

the attention of the Senate as a whole to its concerns and the Minister’s

responses.[50]

The Committee also drew matters relating to legislative instruments (NTAIC

business rules and township leasing) to the attention of the Senate Standing

Committee for the Scrutiny of Delegated Legislation.[51]

It is worth noting that similar concerns about investment

plans by a Commonwealth corporation not being set out in a reviewable

legislative instrument were raised by the Committee with respect to the Investment

Mandate of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land and Sea Future Fund.[52] Unlike the

NTAIC’s Strategic Investment Plan, the Investment Mandate is a

legislative instrument, but it is exempt from disallowance or sunsetting.[53] At that time the

Minister (former Minister Scullion) replied that the Government considered this

exemption was appropriate as it was consistent with other Investment Mandates

administered by the Future Fund Management Agency and provided certainty to the

Future Fund Board of Guardians in pursuing investments.[54]

Policy position of

non-government parties/independents

In his second reading speech on the Bill, Shadow

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus stated that the Australian Labor Party would

support the Bill, based upon the extensive consultation with the Land Councils

that had taken place and the Land Councils’ expressed public support for the

Bill.[55]

The ALP Member for Solomon (NT) Luke Gosling subsequently expressed concerns

about some aspects of the Bill, including the wide discretion of the Minister

over the remaining balance of the ABA and the ABA’s investment strategy, but

continued to express overall approval.[56]

On 18 October 2021, during the Second Reading debate in

the House of Representatives, Leader of the Australian Greens Adam Bandt

expressed concern that the Bill had not been subject to a committee inquiry and

hence affected First Nations groups and communities had not had an opportunity

to be heard.[57]

The Bill was subsequently referred to the Senate Standing Committee on Finance

and Public Administration on its arrival in the Senate (see above).

Independent MP for Clark Andrew Wilkie expressed support

for the Bill but criticised the Government’s overall Indigenous policies.[58]

Position of major interest

groups

The Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Public

Administration inquiry has not yet published any submissions, so there has been

limited opportunity to assess the views of key stakeholders. According to the

Bill’s second reading speech and Explanatory Memorandum, the amendments

proposed have been extensively discussed with the NT Land Councils, the NT

Government, affected communities and mining peak bodies, amongst others.

Minister for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt, noted that

the reforms have been ‘extensively co‑designed with traditional owners in

the Northern Territory and their land councils over the last 3½ years’ and that

the Land Councils have also consulted around 220 elected landowners whose land

generates ABA moneys as part of designing the reforms.[59]

A media release from Ministers Wyatt and McCormack quoted

Mr Sammy Bush-Blanasi, Chair of the Northern Land Council, as saying, ‘This is

a historic moment for Aboriginal Territorians - we will finally have control

over how money generated from mining on our land is spent. This will allow

Aboriginal people to invest in more Aboriginal jobs and support culture and

community for our grandchildren and beyond.’[60]

Financial implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the NTAIC

measures will have a positive impact on the Commonwealth’s underlying cash

balance over time (as set out in the following Table 1).[61] This is presumably because

the NTAIC can be expected to make a higher return on its capital than the ABA.

However, this money will only be available at the direction, and for the

legislated purposes, of the NTAIC.

Table 1: Government estimates on underlying cash balance

| |

|

Impact on underlying cash ($ millions) |

| |

2020-21 |

2021-22 |

2022-23 |

2023-24 |

2024-25 |

Total |

| Expenditure |

0.0 |

+0.1 |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

+1.0 |

+0.4 |

| Revenue |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

+3.2 |

+11.7 |

+14.7 |

| Total |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.4 |

+2.9 |

+12.6 |

+15.1 |

Source: Explanatory

Memorandum, Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment (Economic

Empowerment) Bill 2021, p. 9.

Statement of Compatibility with

Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[62]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

considered the Bill in its 11th report of 2021 and made no comment.[63]

Key issues and provisions

Schedule 1

The first schedule’s amendments:

-

create a Northern Territory Aboriginal Investment Corporation

(NTAIC) (proposed Part VIA of the Act, consisting of proposed sections

65A to 65JE, as inserted by item 6, in particular see proposed

section 65B)

-

lay out its purposes, powers and functions (proposed sections

65BA–65BL)

-

establish a Board for the NTAIC alongside a procedure for

appointing the Board (a majority of which is elected by the four NT Land

Councils), CEO and Committee members (proposed Divisions 5 to 7, Part

VIA) and

-

guide the NTAIC’s investments according to a Strategic Investment

Plan, to be tabled in Parliament (proposed section 65C).

Key Issue: Creation of the NTAIC

The NTAIC is established with the purpose of both

promoting the self-management and economic self-sufficiency as well as the

social and cultural wellbeing of Aboriginal people in the NT (proposed

section 65BA). Its functions include making payments for the benefit of

Aboriginal people living in the NT and making investments in order to advance

its purposes (proposed section 65BB).

The NTAIC is given broad powers by the Bill, and it has

the power to do all things necessary or convenient for or in connection with

its functions (proposed section 65BD). This includes accepting gifts,

borrowing money, making loans, giving guarantees and entering other

arrangements. Many of the provisions note that the NTAI Corporation Rules (made

under proposed section 65JE) can provide details on the exercise of

these functions.[64]

Proposed section 65BH provides for an investment

limit so that the NTAIC cannot make an investment over $100 million without the

Minister’s agreement – this amount can be raised but not lowered by Ministerial

rules. The NTAI Corporation Rules can also set out how the ‘value’ of an

investment is calculated. The Government notes that this provision provides

appropriate Government oversight for very large investments, while safeguarding

the role of the NTAIC (as the limit cannot be lowered).[65] The Scrutiny of Bills

Committee noted that if such investment is erroneously made without the

Minister’s agreement, it is not invalidated (proposed

subsection 65BH(3)).[66]

The NTAIC is Commonwealth body corporate, and so will be

subject to the requirements of the Public Governance,

Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) (proposed

subsection 65B(3)). Typically, a Commonwealth entity that makes

investments would be subject to an ‘investments mandate’ that outlines (among

other things) the expected ‘benchmark’ rate of return that it is required to

make, although this is not a legislative requirement of the PGPA Act.

Such Investment Mandates are often legislative instruments.[67]

The Bill instead provides that the Board must develop a

strategic investment plan (SIP) for the NTAIC which includes information on the

NTAIC’s priorities and principal objectives over a period of three to five

financial years (proposed section 65C). The SIP is not a legislative

instrument but is required to be tabled in Parliament (proposed subsection

65C(8)). Importantly, the Board must consult with both Aboriginal people

and Aboriginal organisations in the Northern Territory in developing the SIP (proposed

paragraph 65C(6)(a)), including Aboriginal people who are not Traditional

Owners and thus not represented by Land Councils. The Board must also consider

any advice given by the Investment Committee set up under proposed section

65FA (proposed paragraph 65C(6)(b)).

Part 2 of Schedule 1 puts in place

transitional arrangements by which members of an Interim Board are appointed by

the Minister and Finance Minister, Land Councils, and the Interim Board, until

full elections for the Land Council members of the Board can be held. This

Interim Board, rather than the first ‘regular’ board, will appoint the first

Independent board members and the first Investment committee, which is

responsible for creating the SIP.

To fund the NTAIC, approximately half ($680 million) of

the current accumulated balance of the ABA ($1.3 billion)[68] will be transferred to the

NTAIC over three years (proposed subsections 64AA(1)-(3) at item 4 of

Schedule 1). The Bill makes provision for further transfers in future, but

these are subject to ministerial discretion (proposed subsection 64AA(4)).

Item 5 also abolishes the current Aboriginals

Benefit Account Advisory Committee (ABAAC), meaning that ministerial

spending from the remaining balance of the ABA will be relatively unconstrained

in future (discussed below). A review of proposed Part VIA of the Act (which

would likely include a review of the NTAIC’s performance) after seven years,

which must be tabled in Parliament, is mandated by proposed section 65JD.

Key Issue: Tensions between

purposes of the NTAIC

The NTAIC’s purposes and functions, laid out in proposed

sections 65BA, 65BB and 65BC mandate, among other things, that:

65BA The NTAIC Corporation is established:

(a) to promote the self management and economic

self sufficiency of Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory; and

(b) to promote social and cultural wellbeing of

Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory.

65BB The NTAIC Corporation has the following functions:

(a) to make payments to or for the benefit of

Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory;

(b) to make investments for the purposes

mentioned in paragraphs 65BA(a) and (b);

(c) to provide financial assistance (other than

payments or investments of the kind mentioned in paragraphs (a) and (b) of this

section), whether on commercial terms or otherwise, to or for the benefit of

Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory

…

65BC General rules about performance of functions

In performing its functions, the NTAIC Corporation

must:

(a) have regard to its purposes under section

65BA; and

(b) have regard to the strategic investment

plan that is in force at the relevant time; and

(c) act in accordance with sound business

principles whenever it performs its functions on a commercial basis; and

(d) maximise the employment of Aboriginal

people living in the Northern Territory; and

(e) maximise the use of goods and services

provided by businesses owned or controlled (whether directly or indirectly) by

Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory.

Thus the NTAIC must act for beneficial or charitable

purposes by promoting social and cultural wellbeing (proposed

paragraph 65BA(b)) and making beneficial payments (proposed

paragraphs 65BB(a) and (c)). It must also act as a long‑term

investment manager (proposed paragraphs 65BA(a), 65BB(b), 65BC(b) and

(c)). In making its investments it is in many ways constrained to investing

in Aboriginal‑related enterprises in the Northern Territory by the

effects of proposed paragraphs 65BC(d) and (e). The NTAIC’s

stakeholders will likely expect the NTAIC to have funds available to make

grants which do not generate direct business returns (proposed paragraphs

65BB(a) and (c); although for these purposes, the Minister may

provide supplemental funds from the ABA). This combination of purposes reflects

the Government’s intention that the Bill provides the NTAIC with broad

functions that it can perform on a commercial or non-commercial basis as

appropriate.[69]

While this combination of purposes has the potential for a

‘multiplier effect’ of positive outcomes through the combination of directed

investment and direct action, it also means that the NTAIC’s investments may be

heavily exposed to the high-risk business environment of Northern Australia,

particularly to Indigenous-owned and community enterprises. As the Joint

Standing Committee on Northern Australia Inquiry into the Opportunities and

Challenges of the Engagement of Traditional Owners in the Economic Development

of Northern Australia has heard,[70]

the Northern Australia business environment faces many challenges and these are

particularly acute for Indigenous businesses, meaning that existing investment

facilities such as the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility have

struggled to find commercially viable projects within its risk appetite.[71]

In addition, the NTAIC may be investing in many businesses

at a very early stage of development. While the SIP will presumably seek to

diversify the NTAIC’s portfolio, it is not clear whether investment under the

SIP is permitted to go outside the sectoral constraints of proposed

paragraphs 65BC(d) and (e). This sectoral exposure runs the risk

that significant portions of the NTAIC’s capital could be lost if a ‘flagship’

investment performed badly (for example, the Indigenous Land Corporation’s

significant loss of capital when the value of Ayers Rock Resort was written

down)[72]

or if some external event affected the NT’s economy (for example, local

recession, or natural disasters such as cyclones or the COVID-19 pandemic with

their impact on tourism-dependent economies).

As the Land Councils and their associated commercial and

investment entities, such as CentreCorp and the Aboriginal Investment Group

(AIG), are also operating in the constrained investment environment of the NT,

managing potential or perceived conflicts of interest between these various

associated entities may be challenging. Recent controversies around the lease

of AIG buildings in Darwin by the Northern Territory Land Council provide one

example.[73]

Given that the NTAIC is required to ‘maximise the use of goods and services

provided by businesses owned or controlled (whether directly or indirectly) by

Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory’,[74] many of which are associated

with Land Councils, such intersections of interests may occur frequently.

Key Issue: Representativeness

and election of the NTAIC Board

Under proposed section 65EA, the NTAIC is to be

governed by a board consisting of two members from each of the four Northern

Territory Land Councils, two members appointed by the Minister and the Finance

Minister, and two independent members appointed by the Board.

Professor Altman has raised concerns[75] that this representation

formula significantly differs from the ABA Advisory Committee (ABAAC)

membership, which currently advises on expenditure under section 65 of the Act.

The ABAAC currently comprises eight members (including the co-chair of the

ABAAC) from the Northern Land Council (NLC), five from the Central Land Council

(CLC), one member from each of the Tiwi Land Council (TLC) and Anindilyakawa

Land Council (ALC), and a ministerially appointed chair.[76] These ABAAC land council

memberships are in some proportion to the Aboriginal population of the area

represented by each land council (see Table 2 below). The Bill’s proposed

membership of the NTAIC Board gives disproportionate weight to the small TLC

and ALC, which may in turn lead to disproportionate investment or expenditure

by the NTAIC in those areas of the NT at the expense of other areas. This is

further highlighted in Table 2 below.

The Explanatory Memorandum provides no explanation for

this weighting of Board seats, instead simply stating that drawing the Board’s

membership from the Land Councils ‘ensures consistency with the architecture of

the Land Rights Act, whereby ABAAC representatives were drawn from the Land

Council membership’.[77]

One possible rationale for this seat distribution is that, if the Government

and Independent members of the Board all opposed a motion, it would only take

one Land Council siding with the Government and Independent members for it to

fail.

Table 2: Comparison of seats on the ABAAC and the proposed

NTAIC Board

| Land Council |

Aboriginal popn. of area

(approx.) |

Seats on ABAAC |

Seats on NTAIC Board |

| NLC |

51,000 |

8 (inc. co-chair) |

2 |

| CLC |

24,000 |

5 |

2 |

| TLC |

2,700 |

1 |

2 |

| ALC |

1,500 |

1 |

2 |

| Government/Independent

Members |

- |

1 |

4 |

| Total |

79,200 |

16 |

12 |

Source: Population estimates

have been taken from the relevant Land Council webpages.

Professor Altman also expressed concern that despite the

NTAIC being established to make investments and payments to or for the benefit

of all Aboriginal people of the Northern Territory, there is no Board

representation of the non-Traditional Owner Aboriginal population of the NT.[78] However, in this

regard, the NTAIC replicates the existing makeup of the ABAAC.

The procedures for electing members to these key positions

are also largely undefined by the Bill. Proposed subsection 65EB(4)

states that ‘A Land Council must conduct an election for the purposes of making

an appointment under subsection (1) [to the board of the NTAIC]. The Land

Council may determine the manner in which the election is to be conducted.’

This contrasts with the requirements of subsection 29(1) of the Act for

electing Land Council members, who are to be ‘chosen by Aboriginals living in

the area of the Land Council in accordance with such method or methods of

choice, and holding office on such terms and conditions, as is, or are,

approved by the Minister from time to time’, thus ensuring that the process has

external oversight via the Minister.

With the Land Councils being granted this flexibility, it is

not clear why an election, rather than a simple ‘choice’ or ‘appointment’, is

mandated in the Bill. Furthermore, while allowing the Land Councils to

determine the manner of the election is in keeping with the goal of

self-determination, and may make pragmatic sense given the logistical

difficulties faced by some Land Councils in coordinating meetings and elections

across many remote communities, the Bill as it stands does not mandate

openness, procedural fairness, or consistency of election conduct from one

election to the next. This raises the possibility that the electoral process

could be manipulated.

Such a possibility could arguably be averted by requiring

the Land Councils or NTAIC to issue written instructions for the conduct of

Board elections as part of the Board’s Code of Conduct (under proposed

section 65EM), which would increase transparency without reducing the

self-determination of the Land Councils. If external oversight or the

possibility of it is required, amendments authorising the Minister to issue

such instructions as part of the NTAIC Corporate Rules under proposed section

65JE could arguably permit this — which would still allow procedural

flexibility but provide for ministerial oversight.

Key issue: Payments by the NTAIC

and their tax treatment

Currently, payments from the ABA for beneficial purposes

under subsection 64(4) of the Act may incur Mining Withholding Tax (MWT), an

income tax (currently set at 4%) levied specifically on Indigenous recipients

of mining payments by Division 11C of the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1936.[79]

Broadly speaking a mining payment is an amount that represents

royalties which have been received by the Commonwealth for the mining of

Indigenous land.[80]

As a withholding tax, although formal legal liability for MWT rests with the

Indigenous recipients, the actual responsibility for paying the MWT rests on

the person or entity who makes the payment: such bodies are required to

withhold an amount from a mining payment in accordance with the

Pay As You Go (PAYG) withholding rules.[81]

In the case of grants made under subsection 64(4), this body is the ABA.

Not all of these payments incur this tax liability, as

payments made out of the investment earnings of the ABA are not mining

payments and hence do not attract MWT. It has become the practice of

the managing agency (currently NIAA) to make section 64(4) payments out of the

investment earnings where possible, so as to minimise the MWT liability of the

recipients of those payments.[82]

However, some payments of MWT for this purpose are still made.[83]

The NTAIC has now been empowered to make beneficial

payments under proposed paragraphs 65BB(a) and (c), a

function for which the Minister may provide them with additional

payments from the ABA under proposed subsection 64AA(4). The Explanatory

Memorandum states that the function of making beneficial payments will now pass

to the NTAIC and beneficial payments will cease to be made from the ABA

(although the Bill does not mandate this – see discussion below).[84] Beneficial

payments made by the NTAIC under proposed paragraphs 65BB(a) and (c) would

appear to not be mining royalty equivalents per se (and hence not mining

payments). It therefore appears that such payments would not impose a

MWT liability on the Indigenous recipients of such payments. The overall

practical effect of the policy change from beneficial grants being made by the

ABA to beneficial grants being made by the NTAIC, for the Indigenous

end-recipients, is that MWT is unlikely to be paid on any such beneficial

grants received from the NTAIC. While the Bill does not amend the application

and operation of MWT under tax legislation and the amounts at stake are not

large, this policy change is of interest given that Land Councils and other

stakeholders have often decried the MWT as an unjustified impost.[85]

Key Issue: The balance of the

ABA and absence of an ABA investment strategy

Since 2006, the combination of rising world mineral prices

(and hence mining royalties) and increased retention of funds in the ABA, as a

result of both ministerial decisions to build the account’s equity, and the

reduced payments to Land Councils stemming from the 2006 amendments, has

resulted in a large balance accumulating in the ABA.[86] On 30 June 2005, the balance

of the ABA was $102.9 million;[87]

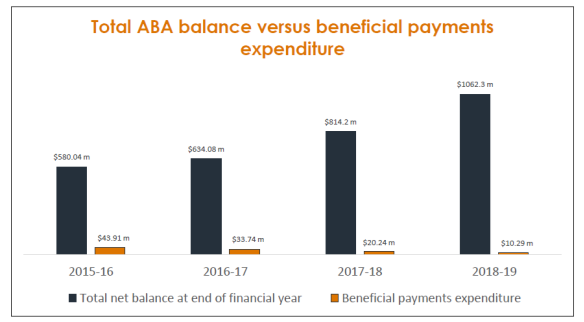

since then, it has risen to exceed $1.3 billion.[88] The graph below shows the

increasing balance of the ABA compared to its static level of beneficial

(section 64(4)) expenditure in recent years.

Increasing balance of the ABA, 2015–2019

Source: NIAA, Supplementary

Submission, op. cit., p. 5.

While maintaining an invested equity reserve in the ABA is

a legitimate and statutory (under section 62A) purpose of the ABA, particularly

considering its dependence on potentially unpredictable and exhaustible mining

revenues, retention of an ever-increasing balance has effectively imposed a

large opportunity cost upon the Aboriginal population of the NT whom the ABA is

intended to benefit. Furthermore, owing to the requirements of the PGPA Act[89] for investing

public funds, the balance of the ABA can only be invested in cash accounts,

term deposits or investment-grade securities such as government bonds.[90] Since 1976, when

the Act was passed, and particularly since the global financial crisis (which

occurred shortly after the 2006 Amendments took effect), the return on such

investments has declined from 10 per cent or more per annum to less than three

per cent per annum.[91]

There is therefore a strong case for reconsidering

management of the ABA and investing the balance in ways which will better

benefit Traditional Owners and the Aboriginal people of the NT. The Bill

accomplishes this in part by creating the NTAIC, which will be empowered to

make investments outside the constraints of section 59 of the PGPA Act

by proposed subsection 65BG(2).[92]

However, a substantial balance ($620 million or more) will remain in the ABA.[93] Without any

change in its investment strategy, the remaining balance in the ABA will thus

continue to earn extremely low returns for the immediately foreseeable future.

Furthermore, as Professor Altman[94]

and former CEO of the ILC Michael Dillon[95]

have both observed, the ABA’s mining royalty equivalent income is likely to

sharply diminish in the near future, as the Groote Eyelandt manganese mine,

which currently provides approximately two-thirds of the ABA’s royalty

equivalent income, is scheduled to close within five years.[96] Under these circumstances, a

higher‑return investment strategy may be the only way for the ABA to

fulfil its legislated functions of providing for Land Council operating

expenses.

The former Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land

Account (the Land Account) provides an interesting comparison in reform of

government special accounts in the Indigenous policy space. Like the ABA, the

Land Account had low returns (which threatened its long-term sustainability)

owing to the requirements of the PGPA Act. The government’s response to

this was to create a new Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land and Sea

Future Fund (ATSILSFF), which is invested by the Future Fund Management

Authority (FFMA).[97]

Unlike the ABA’s transfer of half its balance to the NTAIC, the entire

balance of the Land Account was transferred into this new investment vehicle.

Conversely, unlike the NTAIC, the FFMA is under no obligation to invest these

funds in ways which are beneficial to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

people, other than by producing a sustainable dividend for use by the

Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation, and has no significant Indigenous input or

control into its investment and governance.[98]

The expressed preferences of many Indigenous stakeholders at the time that the

ATSILSFF should be required to take wider Indigenous interests into account,

for example by investing according to the Indigenous Investment Principles,[99] were rejected by

the FFMA and the Commonwealth.[100]

Like the Bill, the creation of the ATSILSFF also removed

without replacement the previous Indigenous oversight body – in that case the

Consultative Forum on investment policy of the Land Account, which had been

convened under former section 193G of the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Act 2005,[101]

and in this case the ABAAC. However, in the case of the NTAIC, the Land

Councils, through the NTAIC Board, will exercise a determinative, not merely

advisory, role over the half of the ABA’s accumulated balance that passes to

their control, and appear to regard this as a worthwhile trade-off.

Key Issue: Increased Ministerial

control over the remaining ABA balance

Item 5 of Schedule 1 repeals section 65 of

the Act. This section creates and governs the Aboriginals Benefit Account

Advisory Committee (ABAAC). Subsection 65(1) currently states ‘There shall be

an Account Advisory Committee to advise the Minister in connexion with debiting

the Account for the purposes of making payments under subsection 64(4).’

The ABAAC is thus the statutory advisor on the Minister’s

power to make payments from the ABA under section 64(4) of the Act (‘There must

be debited from the Account and paid by the Commonwealth such other amounts as

the Minister directs to be paid or applied to or for the benefit of Aboriginals

living in the Northern Territory’). Repealing section 65 has the effect of

abolishing the ABAAC.

For some years, the practice has been that section 64(4)

payments are made through a departmental grant program with grants usually

(though not always) assessed and recommended by both the Department and the

ABAAC before being forwarded to the Minister. The NIAA webpage, ABA Grants

Information and Application Process states:

The Agency assesses every compliant application received by

the closing date.

The Agency provides its assessment to the ABAAC for their

consideration. The ABAAC reviews the proposal and provides advice to the

Minister.

The Minister uses this information when deciding which

applications will proceed to the negotiation of a funding agreement.[102]

The ABAAC only has an advisory function, and the

Minister is not obligated to follow its advice, even under the current

framework. However, the fact that the ABAAC is a legislated body under current

section 65 may mean that if a Minister were to make payments which were

obviously against ABAAC advice, such decisions could possibly be subject to

judicial review and would likely face public scrutiny. The Bill’s abolition

without replacement of section 65 means that payments from the balance of the

ABA (which, even after the Bill’s deductions to endow the NTAIC, will still

exceed $600 million) under section 64(4) would be solely at the discretion of

the Minister, without any legislated scheme for advice put in place. The

practical (albeit not legal) constraint provided by ABAAC on the Minister’s

discretion would therefore be removed.

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill states that the

function of making beneficial grants will now pass to the NTAIC:

With the NTAI Corporation established to make payments to or

for the benefit of Aboriginal people in the NT, it will replace the ABAAC and

empower Aboriginal Territorians to make the payments.[103]

The NTAIC is granted the power to do so by proposed

paragraph 65BB(a) (at item 6 of Schedule 1). The

implication is that the Minister through the relevant agency (currently the

NIAA) will no longer make such payments. However, there is no provision in the

Bill which prevents the Minister from making such payments out of the ABA.

Furthermore, the NTAIC would have financial constraints

upon its grant-making ability which would not apply to the Minister. After

approximately the first two years of operation (during which the NTAIC receives

payments totalling $680 million under proposed subsections 64AA(1)–(3)),

the NTAIC does not receive a guaranteed income from the ABA (with which to make

such grants, or for any other purpose). It must instead fund beneficial

payments either from the return on its investments (which it may wish to

retain, in order to protect the investment capital) or by relying on additional

debits from the ABA at the Minister’s direction (having regard to recent

estimates of the NTAIC’s expenditure) (proposed subsection 64AA(4)).[104]

Under proposed subsection 64AA(4), the Minister

must grant to the NTAIC ‘such amounts as the Minister directs from time to

time’. While this is the same language used to provide for the annual

budgets of the Land Councils under section 64(1), it is nevertheless not a

strong stipulation; it is not required to be annual, nor is any minimum amount

or proportion of the ABA’s mining royalty equivalent income specified by the

section (in contrast to the minimum payments to Traditional Owners under made

under section 64(3) of the Act).[105]

While the NIAA has stated that such payments will be made annually, the Bill

itself does not prescribe this.[106]

Furthermore, the Explanatory Memorandum explicitly states:

Section 64AA(4) is intended to provide a mechanism for

ongoing funding to the NTAI Corporation, whilst balancing its funding needs

with the availability of funding from the ABA. Whilst the Minister must

have regard to certain estimates when making directions under section

64AA(4), this does not preclude the Minister making a direction for an

amount that differs from those set out in the estimates.[107] [emphasis added]

This contrasts, for example, with funding of the

Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation, which receives annual payments of amounts

stipulated by section 22 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land

and Sea Future Fund Act 2018.[108]

Thus, under the proposed amendments, despite the

descriptive intent of the Explanatory Memorandum, the Minister would retain the

power to make grants from the existing ABA under subsection 64(4), without

being advised by the ABAAC. The Minister is not required to grant money

with any regularity to the NTAIC for the purposes of beneficial grants, and

could effectively limit the NTAIC’s grant budget by making smaller payments

than requested, using their discretion under proposed subsection 64AA(4).

There could be potential political incentives for a Minister to retain grant

giving power and money using this mechanism. As a number of controversial

payments out of the Indigenous Advancement Strategy and ABA funds by former

Minister Scullion showed, the range of payments which a Minister might claim

were ‘for the benefit of Aboriginals living in the NT’ under s 64(4) could be

quite broad.[109]

Commonwealth grants programs have come under increasing

scrutiny for their purported/alleged use for political purposes in recent times

(see, for example, recent commentary around the Community Sport Infrastructure

Grant Program and the Commuter Car Park Program). These political controversies

have led to calls for reforms to the legal and administrative frameworks that

govern Commonwealth grants.[110]

In this environment, it should be noted that the removal of the ABAAC’s

advisory function may in practice lead to increased Ministerial

discretion in relation to the allocation of payments from the ABA than is the

case under the current framework, although, owing to the transfer of half of

the balance of the ABA to the NTAIC, the amount which the Minister controls is

reduced.

Of Interest: Power of the Minister to approve the CEO

The Board of the NTAIC is only able to appoint (proposed

section 65GB) or terminate (proposed section 65GI) a CEO with the

written agreement of the Minister. This contrasts with the CEOs of the

comparable Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation (ILSC) and Indigenous Business

Australia (IBA), both of which are appointed solely by the Boards of those

corporations (see sections 168 and 192K of the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Act 2005). The Explanatory Memorandum states

that this ‘ensures Commonwealth oversight of the appointment’ without

explaining why this additional oversight is considered necessary.[111]

Schedule 2 Amendments: Mining

related decision making

The second schedule implements several amendments

recommended by the Aboriginal Land Commissioner’s 2013 Review of Part IV of

the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 concerning mining

activity under the Act.[112]

These amendments update the Act to reflect relevant Northern Territory

legislation and developments in mining (such as those concerning geothermal

energy), clarify and change aspects of the approval process (including meeting

consent requirements with Traditional Owners), clarify the process for dealing

with relatively low impact mining for extractive minerals (clay, gravel, sand,

et cetera), and change parts of the Ministerial delegation and approval process

by removing delegation of some Commonwealth ministerial approvals to the

Northern Territory mining Minister and removing the requirement for

Commonwealth ministerial approval for some mining projects.

Item 21 makes amendments to enable a Land Council

to determine whether an exploration application does or does not substantially

comply with the legislated application requirements under subsection 41(6), and

provides the applicant with the opportunity to vary or resubmit their

application in a compliant form. Currently the relevant provision (subsection

41(6A)) simply states that strict compliance with the legislated requirements

is not required and ‘substantial compliance’ is sufficient, without explicitly

enabling the Land Council (or any other party) to determine what constitutes

‘substantial’ compliance. This amendment was not the subject of a

recommendation in the 2013 Review, but the increased procedural flexibility

would seem to be in the interests of all parties.

Item 23, inserting proposed subsection 42(4),

grants Land Councils slightly greater power to determine whether meetings with

the Traditional Owners are convened to discuss an application, or a variation

of an application, in line with Recommendation 6 of the 2013 Review.[113] The 2013

Review noted that such an amendment would be in the interests of efficiency and

timely addressing of applications.[114]

In the light of recent disputes between, for example, the

Northern Land Council and persons who were, or claimed to be, traditional

owners in the Beetaloo Basin, this proposed subsection may be of particular

interest to Parliament.[115]

Currently paragraph 42(4)(a) mandates that ‘the Land

Council shall convene such meetings with them [Traditional Owners] as are

necessary for the purpose of considering the exploration proposals and the

terms and conditions’.

The proposed subsection reads:

42(4) To facilitate consultation between the Land Council

and the traditional Aboriginal owners, the Land Council must:

(a) subject to

subsection (4A), convene such meetings with them, after the Land

Council determines under subsection 41(7) that it is satisfied the

application complies substantially with subsection 41(6), as the Land

Council considers appropriate for the purposes of considering the

exploration proposals and the terms and conditions…[emphasis added]

While noting that current paragraph 42(4)(a) might already

give Land Councils the flexibility to determine that a meeting is not

necessary, proposed paragraph 42(4)(a) gives the Land Council greater

freedom to determine whether holding a meeting with Traditional Owners is or is

not appropriate, which might conceivably work against Traditional Owner

interests if a Land Council were to restrict meetings in order to prevent

objections to a mining project. In other words, the amendments appear to make

the question of requiring a meeting with Traditional Owners as a question to be

solely determined in the view of the Land Council (that is, what the Land

Council considers appropriate for the exploration proposals and terms

and conditions to be considered becomes the key factor). Under the current

framework, arguably, such meetings may be required where considered objectively

‘necessary’ for considering proposals and terms and conditions. The amendments

may give the Land Council more power in this regard.

Proposed subsection 42(4B) also grants extra

decision-making flexibility to Land Councils, potentially at the expense of

Traditional Owners, by enabling Land Councils to accept variations to an

application after the original application has been discussed by Traditional

Owners, without holding a meeting to consider the varied application, as long

as the relevant matters were discussed at one or more of the original meetings.

One could easily imagine situations in which Traditional Owners might consent

to an original application but not to some variation of it.

However, these proposed subsections are still subject to

sections 42(2) and 42(6) of the Act (as amended by the Bill):

42(2) The Land Council must not consent to the grant of

the licence unless it has, before the end of the negotiating period, to the

extent practicable:

(a) consulted the

traditional Aboriginal owners (if any) of the land to which the application

relates concerning:

(i) the exploration proposals; and

(ii) the terms and conditions to which the grant of the licence may be

subject; and

(b) consulted any

Aboriginal community or group that may be affected by the grant of the licence

to ensure that the community or group has had an adequate opportunity to

express to the Land Council its views concerning the terms and condition

…

42(6) Subject to subsection (7), the Land Council

must not consent to the grant of the licence unless:

(a) it is satisfied

that the traditional Aboriginal owners (if any) of the land understand the

nature and purpose of the terms and conditions and, as a group, consent to

them;

(b) it is satisfied that the terms and conditions are reasonable; and

(c) it has agreed with the applicant upon the terms and conditions.

Thus Land Councils would still be bound by the requirement

to be satisfied that the Traditional Owners as a group consented to the

original licence and its terms and conditions, and the requirement to be

satisfied that those terms and conditions were reasonable. If Land Councils

were to use the proposed increased procedural powers and flexibility to

circumvent Traditional Owner consent (for example by considering that a meeting

was not ‘appropriate’ and so not holding one) they would risk the grant of a

licence being found invalid under subsections 42(2) or 42(6).

Item 25 make amendments that remove the requirement

for Commonwealth Ministerial consent to an exploration licence after the Land

Council has consented. This is a strengthening of Aboriginal decision-making

power, as it prevents the Minister overruling a decision of the Land Council,

and also removes a potentially significant delay (up to 30 days) from the

application process, which could otherwise cause significant and unnecessary

expense to applicants.

However, it does remove a potential check-and-balance from

the current licence granting process, inasmuch as the Minister may consider

other factors (such as submissions from minority Traditional Owners, or from

other non-Traditional Owner Aboriginal people affected by a development, or any

other factors), which a Land Council is not bound to consider. Similarly, the

Minister may believe that a Land Council or Traditional Owner is being in some

way deceived or short-changed by an applicant, or in some other way the

national interest is not served by granting a licence. For this reason the

proposal to remove this section was opposed by Land Councils at the time of the

2013 Review.[116]

However, Recommendation 9 of the 2013 Review recommended that consideration

should be given to whether the Ministerial consent requirement added ‘quality’

to the approval process and, if it did not, to repealing it, with the

Commissioner noting that the current lack of substantive information provided

to the Minister on a licence decision mean that it is not an effective

‘backstop’.[117]

It appears that the result of this consideration has been to repeal the consent

process.

The Minister does retain powers under section 47 of the

Act to cancel exploration licences or mining interests if the exploration or

mining is not, or is likely not to be, in accordance with the terms and

conditions, and is having or is likely to have significant impacts on the

affected land and Aboriginal peoples. Therefore the Minister retains an

‘emergency override’ power.

This ‘emergency override’ federal power is effectively

strengthened by item 51 which widens the scope of matters which cannot

be delegated to the Northern Territory Mining Minister from only those parts of

subsections 47(1) and (3) explicitly concerning the national interest, to all

of subsection 47(1) (exploration) and subsection 47(3) (mining) powers. As the

2013 Review noted, the federal Minister for Indigenous Australians is more

likely to be able to consider the environmental, social and cultural factors at

stake than the NT Mining Minister.[118]

Other Ministerial powers in Part IV do not appear to be

affected by the Bill. For example, where consent is refused and the application

is placed into moratorium for five years, a Land Council can still apply to the

Commonwealth Minister to recommence negotiations (subsection 48(3)). In

addition, Northern Territory law will still require consent to be given by the

Northern Territory Minister to commence negotiating with the Land Council (see,

for example, section 62 of the Mineral Titles Act 2010[119] or section 13 of the Petroleum

Act 1984).[120]

This requirement is provided for in Commonwealth legislation by subsection

41(1) of the Act.

Item 36 of Schedule 2 to the Bill, proposing replacement

subsection 44A(1), enables the terms and conditions of an exploration

licence to include compensation for the value of minerals removed or proposed

to be removed. This is precluded under current subsection 44A(1) of the Act.

This reform is necessary because of previous reforms to

the mining approval process first introduced in the Aboriginal Land Rights

(Northern Territory) Amendment Act (No 3) 1987.[121] Before that time, two

approval processes were needed for mining-related activity on Aboriginal land;

approval for exploration, and then approval for mining. This dual approval

process was objected to by mining companies, as it meant that they might

potentially find a valuable deposit while exploring but be forbidden from

exploiting it.[122]

The 1987 Amendments conjoined these processes so that only one approval (or

veto) from Traditional Owners was needed or could be exercised, although there

are still separate agreement-making processes for exploration and mining.

This conjoined process created its own problems, as

Traditional Owners sought details of any proposed mining activity in the

exploration permission application before granting it, lest they find

themselves consenting to mining projects without knowing the details. It is

clearly difficult for companies to predict what the scope of a mine might be,

when they have not yet done any exploration and so do not know what minerals,

in what geographical and geological location, are in situ. Another

result was that exploration agreements ended up including agreements on mining

royalty terms in the event that exploitable resources were found, a practice

which potentially contravened current subsection 44A(1).

The 2013 Review discussed this situation at length but did

not recommend any changes to the approval and veto process at this stage, other

than by amending subsection 44A(1) to recognise current practice

(Recommendation 13).[123]

Schedule 3

Schedule 3 of the Bill makes changes to land

administration and control processes including those for township leases, land

in escrow, ministerial approvals, and control over access to Aboriginal land.

In part these reverse or alter contentious amendments made in 2006 and 2007.

Key Issue discussion: Township Leases

The purpose of Part 1 of Schedule 3 is to enable community

corporations (CATSI corporations) formed under the Corporations

(Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI Act),

rather than the Executive Director of Township Leasing (EDTL), to hold the

head-lease of townships on Aboriginal land rights land. Such arrangements

already exist for the towns of Gunyaŋara

and Jabiru,

the first being enabled by Ministerial approval and the latter by amendments to

the Act passed in 2020 (the Aboriginal Land

Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment (Jabiru) Act 2020) as part of the

handback of Jabiru to the Mirrar Traditional Owners.[124] Similar arrangements are in

train in Muṯitjulu and Pirlangimpi (the Muṯitjulu

lease is a sublease of the Uluru Kata-Tjuta national park, rather than a

township lease under the Act).[125]

The Bill proposes a statutory process for the approval of

CATSI corporations to become the head-leaseholders of townships, in place of

these one-off arrangements. The proposed statutory process provides greater

clarity on requirements to be met for this approval, including:

-

the relevant Land Council has nominated the CATSI corporation (proposed

paragraph 3AA(2)(a))

-

members of the corporation are either the Traditional Owners for

all or part of the area or are Aboriginal people who live in the area (proposed

paragraph 3AA(2)(b)).

Issues relating to the township leasing model

Township leasing under the Act was established by the 2006

Amendments and the subsequent Aboriginal Land

Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment (Township Leasing) Act 2007.[126] Leases

have been usually administered by the Executive Director of Township Leasing

(EDTL) and the Office of Township Leasing (OTL). They are intended to be a

means by which Aboriginal traditional owners in the NT can leverage benefits

such as individual home ownership for Aboriginal people and market rental

payments through the application of a managed sub-leasing scheme.[127]

According to the 2018–19 Annual Report of the Executive

Director of Township Leasing, the OTL held leases over eight townships, 26

housing developments, 17 Alice Springs town camps, and administered the leases

of 74 parcels of land used for Commonwealth assets.[128] The OTL claims that these

leases were actively contributing to economic development and individual home

ownership in many of these towns.[129]

The expenses of the OTL and of Commonwealth leases over land are paid out of

the ABA, instead of government consolidated revenue, a practice which has

frequently attracted criticism.[130]

Professor Altman has calculated that over the course of its existence since

2007, the OTL has cost the ABA approximately $50 million (some of which was

payments to Traditional Owners), while recouping $17 million in rent.[131]

Township leasing was originally established in the 2006

Amendments, and then augmented in 2007, as part of a package of reforms which

were hostile to the communal nature of land rights and the power of the large

land councils. The Howard Government and numerous commentators believed that

economic development required the introduction of individualised, tradable and

bankable property titles in towns and settlements on Aboriginal land. The two

larger land councils perceived the township leases, in combination with

provisions which could see them delegate their powers to local CATSI

corporations and the 2007 Northern Territory Emergency Response which imposed

compulsory five-year leases in many communities, as an attack on land rights,

and so were hostile to their introduction. For many years the only township

leases taken up were in the Tiwi and Groote Archipelagos covered by the smaller

land councils. Township leasing was not a policy priority for the 2007–2013 ALP

Government and so no new township leases were signed during that time, although

many new section 19 leases were established to provide secure tenure for public

housing and infrastructure investment.[132]

When the Coalition returned to power in 2013, it

recommenced negotiations with the mainland Land Councils and eventually adopted

a model of ‘community led’ township leasing that was proposed by several

Aboriginal leaders including Galarrwuy Yunupingu. The first such lease was

established in 2017 over Muṯitjulu as a sublease from the Uluru

Kata-Tjuta National Park, rather than a township lease under the Act. It is

still being managed by the EDTL while a community entity builds capacity for a

takeover of the lease.[133]

Jayne Weepers, Visiting Fellow at the Centre for

Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (Australian National University) notes that

despite the stated intent of township and other such leases being to promote

private economic development, the vast majority (~90%) of township subleases

and section 19 leases in CLC land have been taken out by government

entities (Commonwealth, territory and local), with the remainder largely taken

up by NGOs (many of which would be providing contracted quasi-governmental

services, for example, running Community Development Programs).[134] The major

economic effect, rather than promoting private enterprise, has been an

increased income stream for Traditional Owners from rental payments, the

majority of which is directed to community beneficial projects run by the land

councils or the town CATSI corporations. Thus the net effect of land reforms so

far has been to entrench the role of governments and land councils,

rather than promoting private sector alternatives.[135]

This may support the position of many stakeholders,

including the NLC and CLC, who have argued that barriers to private sector

development in remote communities are not linked to whether tenure is

‘communal’ or ‘private’, but to the more prosaic factors of distance and local

poverty, and the resulting lack of economic opportunities.[136] Given the relatively early

stages of such tenure changes, it is still possible that they will support more

private sector development in future, particularly given that leases may now be

perceived as community-led, rather than imposed.

Stakeholder concerns on township leasing reforms in the

Bill

Some commentators have raised other concerns about this