Introductory Info

Date introduced: 7 October 2020

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: The day after Royal Assent.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Economic

Recovery Package (JobMaker Hiring Credit) Amendment Bill 2020 (the Bill) is

to amend the Coronavirus

Economic Response Package (Payments and Benefits) Act 2020 (the Payments

and Benefits Act) to enable payments to be made to help improve

people’s prospects of gaining paid employment or to increase workforce participation,

between 7 October 2020 and 6 October 2022.

The Bill also allows for the establishment of a scheme

related to one or more of the payments intended to help improve people’s

prospects of gaining paid employment or increasing workforce participation.

Background

The Bill seeks to give effect to the JobMaker Hiring

Credit that was announced as part of the

2020–21 Budget.[1]

The details of any scheme created under the Bill will be contained in rules rather

than in the Payments and Benefits Act. What the Bill enables is broader

than the measure announced in the Budget.

The JobMaker Hiring Credit is a wage subsidy program for

people up to 35 years of age. The Government expects the measure to cost ‘$4.0 billion

over three years from 2020–21’.[2]

Under the JobMaker Hiring Credit, eligible employers who

are able to demonstrate that a new employee is additional (by proving a higher

employee headcount and payroll) will receive a credit of up to $200 per

week for employees aged 16 to 29 years and $100 per

week for an employee aged 30 to 35 years.[3]

The credits, which are claimed quarterly in arrears by the employer, are paid

for a period of ‘up to 12 months’.[4]

In order to qualify for a credit, a job seeker must have worked ‘a

minimum of 20 hours per week, averaged over a quarter’, and have

been in receipt of a working age income support payment for at least

one month out of the three months prior to their being hired.[5]

Job seekers are able to be employed on a permanent, casual or fixed-term basis.[6]

Treasury estimates suggest that the JobMaker Hiring Credit

will support around 450,000 positions for young people, resulting in around

45,000 additional jobs.[7]

Further details on the JobMaker Hiring Credit are set out

in the Government’s fact sheet and the Treasury submission to the Senate

Committee inquiry into the Bill.[8]

The stated objective of the JobMaker Hiring Credit is to

help ‘accelerate growth in the employment of young people during the

COVID-19 recovery. This will improve their economic, health and social outcomes

and reduce the scarring from long term unemployment’.[9]

Essentially, the JobMaker Hiring Credit seeks to create additional jobs and

reduce the risk of young people becoming dependent on income support by

providing an incentive to employers to bring forward their recruitment

decisions and fill new positions with young people.[10]

The targeting of the JobMaker Hiring Credit towards young

people is also in recognition of the fact that this group has been

disproportionately affected by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared

with other age groups.

Youth employment and unemployment,

post-COVID-19

People in younger age groups have been the most affected

by COVID-19, with larger decreases in employment and bigger increases in

unemployment than other age groups. This is in large part because the youth

labour market is characterised by higher levels of employment in service

industries that require close interaction with consumers. It is these

businesses that have been hardest hit by the COVID-19 restrictions.

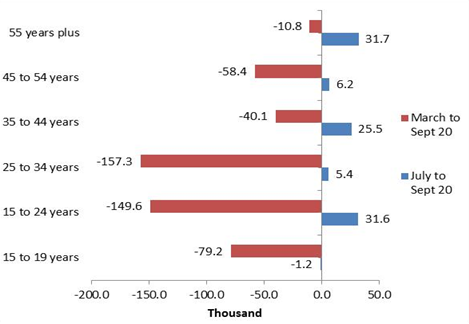

Employment for people aged 25 to 34 years fell by 157,300

(or 5.1 per cent) between March and September 2020 while employment for people

aged 15 to 24 years fell by 149,600 (or 7.7 per cent). There have been signs of

a modest recovery in employment for those aged 15 to 24 years more recently

with an increase of 31,600 in the two months to September 2020. However, there

are fewer signs of improvement for those aged 25 to 34 years (up 5,400). See

Chart 1.

Total employment fell by 425,100 or 3.3% in the six months

to September.

Chart 1—change in employment

by age—March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted

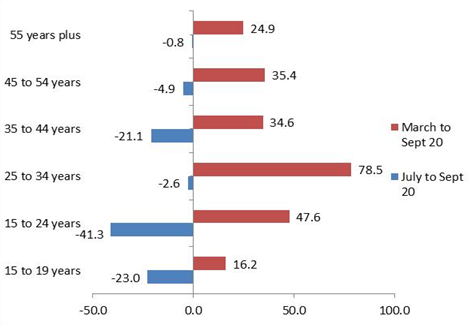

People aged 25 to 34 years recorded the biggest increase

in unemployment between March and September 2020 (up 78,500 or 50.9 per cent)

with only a very small decline (of 2,600) in the most recent two months. Young

people aged 15 to 24 years experienced the next biggest increase in

unemployment (up 47,600 or 18.7 per cent) in the six months to September 2020

but a substantial fall in unemployment for this group has occurred in the past

two months (at 41,300). See Chart 2.

Total unemployment reached just over 1 million in July 2020

but has since fallen to 937,400 in September. Total unemployment is up by

221,600 or 31.0 per cent since March.[11]

Chart 2—change in

unemployment by age—March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted

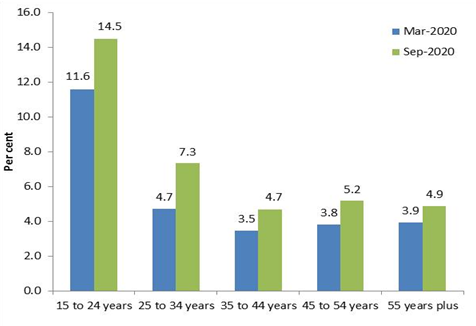

People aged 15 to 24 years experienced the largest

increase in their unemployment rate (up 2.9 percentage points to 14.5 per

cent) followed by those aged 25 to 34 years (up 2.6 percentage points to 7.3

per cent). See Chart 3.

Chart 3 —change in unemployment

rates by age—March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted.

Committee

consideration

The Bill has been referred to the Senate Economics

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 6 November 2020.[12]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Australian Labor Party (Labor)

Labor has criticised the JobMaker Hiring Credit scheme on a

number of grounds.

Shadow Employment Minister, Brendan O’Connor, has

expressed concern over the lack of detail—and, in particular, the lack of

safeguards—in the Bill. Relatedly, Mr O’Connor has criticised the

open nature of the Bill, which allows for the Treasurer to create new

employment schemes that could result in the Government ‘directing

payments to specific and politically favourable companies, donors or

electorates’.[13]

Another issue raised by Mr O’Connor has to do with

the interaction between the JobKeeper subsidy and the JobMaker Hiring Credit.

He appears to be concerned that, following the removal of the JobKeeper subsidy,

many businesses will not be in a position to increase their employee headcount

above previous levels and thus gain access to the hiring credit.[14]

Mr O’Connor has insisted that Labor needs to see

further details relating to the operation and integrity of the scheme,

including details of safeguards to ensure against older workers being replaced

by younger, subsidised workers, and Treasury modelling of its likely impacts.[15]

The Greens

The Australian Greens are highly critical of the JobMaker

Hiring Credit.

Adam Bandt has argued that, under the scheme, taxpayer

monies that could be directly invested in creating jobs and lifting wages will

instead be used to part-pay large corporations’ wage bills.[16]

Mr Bandt has also criticised the lack of protections and

safeguards in the Bill.[17]

Position of

major interest groups

Business groups

Judging by submissions to the inquiry into the Bill and

media statements, many larger Australian businesses and business representative

organisations are, on the whole, supportive of the JobMaker Hiring Credit.[18]

For example, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and

Industry (ACCI) has stated that ‘as a key policy of the Federal Budget,

the JobMaker Hiring Credit is a welcome, practical measure to help address

rising youth unemployment which has been exacerbated by the COVID

pandemic’.[19]

ACCI chief executive James Pearson is said to have stated that the JobMaker

Hiring Credit would ‘tip the balance for many employers in favour of

putting someone on … wage subsidies will have a particular impact in

industries where restrictions are easing but growth is slow or inconsistent.

Accommodation and food services firms have shed around 140,000 jobs since

March. They will need to hire staff as more restrictions are eased’.[20]

Business support for the hiring credit is not universal,

however, with the Council of Small Business Organisations Australia (COSBA)

having expressed a number of concerns with the scheme from the perspective of

small and medium sized enterprises (these are canvassed in the Key issues

and provisions section below).[21]

Unions

Australian unions have highlighted a number of perceived concerns

with the Bill and the JobMaker Hiring Credit scheme.

Chief among these are that the scheme’s safeguards

are insufficient to ensure against employers ‘rorting’ the scheme,

and are to be specified in rules rather than the Bill, and that the scheme, as

it is currently configured, will result in an increase in part-time and

insecure work.[22]

Further details of Australian unions’ positions are outlined in the Key

issues and provisions section, below.

Australian Council of Social

Service (ACOSS)

ACOSS is broadly supportive of the JobMaker Hiring Credit.

It has recommended a number of changes to the scheme, the most substantive of

which are a proposal to target credits based on duration of unemployment and to

increase subsidies for positions offering longer hours.[23]

For further details of ACOSS’ position, see the Key issues and

provisions section.

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum estimates that the JobMaker

Hiring Credit program enabled by the Bill will involve a cost of $4.0 billion

over the 2020–21, 2021–22 and 2022–23 financial years.[24]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[25]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee had no comment on the

Bill.[26]

Key issues

and provisions

The Payments and Benefits Act was legislated primarily

to enable the provision of payments under the JobKeeper Payment scheme.[27]

The Bill essentially extends the payments that can be made under the Payments

and Benefits Act so as to give effect to the JobMaker Hiring Credit scheme.[28]

Item 3 inserts proposed subsection 7(1A),

the effect of which is to enable the Commonwealth to make rules that provide

for payments to help improve people’s prospects of gaining paid

employment or to increase workforce participation during a relevant period.

Item 2 of the Bill inserts the definition of the term relevant period

into section 6 of the Payments and Benefits Act. This will be the period

between 7 October 2020 and 6 October 2022. Proposed subsection 7(1A) provides

for the making of rules about the establishment of a scheme related to one or

more of the payments enabled by the Bill.

Lack of program detail and

protections in the Bill

Some stakeholders have expressed concern about the lack of

detailed information on the JobMaker Hiring Credit, and safeguards against its

misuse by employers, in the Bill.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum:

Rules will be made by the Treasurer to establish the JobMaker

Hiring Credit scheme, including setting out:

- which

employers qualify for the payment;

- the

employees to which payments relate;

- the amount

payable and timing of payments; and

- the

obligations for recipients of the payment.[29]

The rules would take the form of a legislative instrument.[30]

Section 42 of the Legislation Act

2003 allows for the disallowance of legislative instruments by

Parliament. A legislative instrument can be subject to disallowance if either a

Senator or Member of the House of Representatives moves a motion of disallowance

within 15 sitting days of the day that the legislative instrument is tabled.

The motion to disallow must be resolved or withdrawn within a further 15

sitting days of the day that the notice of motion is given. However, if there

is no notice of motion to disallow a legislative instrument, then there is no

debate about its contents.

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee examines each Bill

introduced into the Parliament with regard to, among other things,

‘whether any delegation of legislative powers is appropriate’ and

‘whether the exercise of legislative powers is subject to sufficient

parliamentary scrutiny’.[31]

The Committee has not yet reported on the Bill.

The Government appears to have chosen to include program

rules and requirements in a legislative instrument rather than the Payments

and Benefits Act itself largely as a means to increase its ability to

respond to changing circumstances. According to the Treasury submission to the

inquiry into the Bill, ‘implementing the policy design through rules will

provide flexibility to respond to any unintended consequences, and a rapidly

changing labour market, while still allowing consultation to ensure that the

rules will work as intended’.[32]

The question is: has an appropriate balance been struck

between the need to allow for flexibility in the scheme and the need for

Parliamentary oversight and strong protections against potential employer

exploitation?

Issues associated with wage

subsidies

Perhaps the main issue associated with wage subsidy

programs is that they can potentially have distortionary displacement effects.

For example, subsidies may be associated with ‘deadweight effects’,

as employers hire job seekers with a wage subsidy that they would have hired

anyway.

Another problem is that wage subsidies can result in

worker substitution, with job seekers eligible for the subsidy being hired at

the expense of existing workers and other job seekers who are not eligible for

a subsidy. Sometimes wage subsidies are used with the primary objective of

achieving equity objectives and in these instances the substitution effect is

less of a concern. However, in the case of the JobMaker Hiring Credit, the key

objectives are additionality—the creation of new positions—and

ensuring that young people do not remain on income support.

A further issue with wage subsidies is that they may lead

to employers who do not take advantage of wage subsidies losing business to

those that do.

A number of studies have found positive employment effects

for youth wage subsidies, but this is very much contingent on the design and

implementation of the programs.[33]

If a wage subsidy program is to yield positive outcomes—in this case the

creation of additional, lasting employment at a reasonable cost to

government—then it is important that the program should be well designed.

According to labour market economist, Jeff Borland, among

other things, wage subsidy programs need to:

- have

subsidies that are matched to the state of the macro-economy (typically with

higher subsidies in worse economic conditions)

- target

those job seekers who are hardest hit in times of economic downturn (in this

case, primarily young people who, as a result of their lack of employment

experience, often have lower levels of initial productivity)

- be

of sufficient duration to ensure that job seekers have an opportunity to gain

work experience and skills and demonstrate their value to employers

- be

structured to safeguard against potential employer exploitation

- impose

minimum and maximum hours per week for which a subsidy would be paid and

- be

as simple as possible to administer so as to maximise employer take-up.[34]

Are program safeguards sufficient

to protect against worker substitution?

In its submission to the inquiry into the Bill, Treasury has

provided details of JobMaker Hiring Credit scheme features that are calculated

to ensure the scheme is not misused by employers, along with their rationale.

The main features are:

- additionality

criteria under which employers will be required to demonstrate that their staff

head count and total payroll exceeds a baseline amount at 30 September 2020

(these criteria are intended to mitigate against the possibility of worker

substitution)

- a

requirement that the job be at least 20 hours a week averaged over a quarter

and the spreading of the credit across 12 months rather than providing it

up-front (to counter the risk of employers exploiting the scheme)[35]

- limiting

eligible employees to those who have recently been on income support (to

counter the possibility of businesses classifying independent contractors or

family members as employees to claim the credit)

- requiring

businesses to hold an Australian Business Number (ABN), be up to date with tax

lodgement obligations, be registered for Pay As You Go (PAYG) withholding and

reporting employee payroll information to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO)

through Single Touch Payroll (STP)(to limit the risk of new businesses making

non-genuine claims)

- not

allowing new businesses to claim for their first employee (that could

potentially be themselves)

- making

payments in arrears (to ensure that scheme requirements are met before credits

are paid) and

- use

of the STP system to claim credits and ATO data matching with Services

Australia.[36]

Treasury also notes that the Payment and Benefits Act

contains integrity rules[37]

that ‘authorise the Commissioner of Taxation to take action against

contrived arrangements entered into to gain the benefit of the JobMaker Hiring

Credit’, and that the unfair dismissal and general protections provisions

of the Fair Work

Act 2009 provide additional protections.[38]

The above protections are insufficient to allay the

concerns of some critics of aspects of the proposed scheme. A number of submissions

to the inquiry into the Bill have argued that the headcount and payroll

additionality tests are inadequate to safeguard against worker substitution.[39]

This is largely because, as Per Capita explains:

… because the stipulated minimum hours of employment to

qualify for the scheme are just 20 per week, an employer could retrench one

full time (40 hour per week) worker and hire two subsidised part-time or casual

workers on a marginally increased hourly rate and still meet the additionality

criteria under the scheme.[40]

Some commentators have proposed changes to the scheme that

could help to deal with this potential problem. For example, ACOSS has

recommended that hiring credits should be included when calculating a

business’s overall payroll, thereby reducing any ‘financial benefit

for employers from restructuring their workforce to take advantage of the

subsidy (without actually increasing the paid working hours of employees

overall)’.[41]

ACOSS has also recommended that integrity measures used to reduce the risk of

displacement in other wage subsidy programs should be included in the JobMaker

Hiring Credit scheme’s rules.[42]

The Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union (AMWU)

has advocated that the scheme be amended to ensure that hours of employment for

existing workers must not be reduced by any employer seeking to access the

subsidy. It has also suggested that the problem of worker substitution could be

partly solved by removing the incentive for business to hire workers on 20

hours a week.[43]

Were such a change to be made then this would also help to address another

significant concern with the scheme; namely, that it will result in an increase

in insecure work.

Promotion of insecure work

In its submission to the inquiry into the Bill, Treasury

provides the rationale for the 20 hours per week on average requirement:

This seeks to increase the work experience level of someone

that was previously on income support, with a view to increasing their future

longer term employment opportunities. This level of hours seeks to strike a

balance between providing that opportunity, lifting overall employment

opportunities, and making the subsidy accessible and attractive to employers to

take on employees that may have less experience.[44]

In its current form, the hiring credit could indeed

maximise employment opportunities for young unemployed people and reduce the

number of income support recipients. However, a number of commentators have

argued that this would be at a significant cost to many young workers, as well

as to overall employment conditions, and, ultimately, the economy as a whole.

Under the scheme as it stands there is an incentive for

employers to hire part-time rather than full-time workers as a means to

maximise the number of credits claimed and reduce labour costs. This, some

argue, will result in an increase in already high levels of part-time and

insecure work, especially among young people.

For young workers in low paid jobs or to whom junior rates

apply, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) has expressed the concern

that 20 hours a week of work will provide insufficient income to cover basic

living expenses.[45]

Per Capita has argued that by encouraging the creation of insecure, casual

employment, the scheme’s design will ‘reduce the prospect of the

creation of permanent full-time jobs, which our economy desperately needs to

lift wages and productivity’.[46]

A number of proposals have been made for changes to the

scheme that, it is argued, would help to create good quality jobs and an

inclusive and sustainable recovery.

The AMWU has recommended that the scheme should be amended

to pay higher credits to employers that offer good quality jobs—that is,

jobs that are full- or part-time rather than casual or contract employment,

well remunerated and ongoing. It has also suggested that the higher rates of

subsidy could be paid to encourage improved employment conditions in industries

that have traditionally relied on temporary visa workers, and to attract

private sector investment in areas that are likely to drive future

productivity.[47]

ACOSS has similarly argued that hiring credits—along

with all other wage subsidies—should be doubled for positions averaging

30 hours a week or more. It argues that this change could be achieved

‘without imposing excessive administrative burdens on employers or the

ATO’, given that ‘the scheme already requires information on

average hours worked to enforce the minimum threshold of 20 hours a

week’.[48]

Per Capita has suggested that the incentive for employers to hire part-time and

temporary workers could be reduced by reserving at least 60 per cent of the

hiring subsidy ‘to apply only to new permanent part- or full-time jobs’,

and by tapering the scale of the remaining 40 per cent of the subsidy according

to the number of hours worked by subsidised employees.[49]

The Grattan Institute has proposed as an alternative to

the JobMaker Hiring Credit a generalised incremental payroll rebate. Such a

rebate would subsidise any increase in a business’s payroll expenditure

by allowing a percentage of expenditure rebate on incremental payroll growth

above a baseline point in time. As such, it would ‘encourage expansion of

hours worked by existing staff, and would not bias job creation towards

part-time instead of full-time roles’.[50]

Professor Jeff Borland has pointed out that such a scheme could result in the

subsidising of increased wages and not necessarily increased hours or numbers

of people employed.[51]

As such, it would not provide the same incentive to hire new employees that a

measure like the JobMaker Hiring Credit does.

Discrimination against older workers

and job seekers

A majority of submissions to the inquiry on the Bill acknowledge

that young people have been particularly hard-hit by the COVID-19-related

recession, and that, based on the experience of past economic downturns, they

are likely to suffer the most from long-term consequences should unemployment

remain at current high levels.

Nevertheless, a number of commentators have pointed out

that a significant number of older Australians are also unemployed, and that

they, too, are a vulnerable group in the labour market.[52]

This is because, among other things, older people typically experience greater

difficulty than younger people in re-entering employment once they become

unemployed.[53]

As it stands, the JobMaker Hiring Credit scheme is likely

to benefit young people at the expense of older job seekers. It offers an

obvious incentive to hire younger job seekers rather than older job seekers.[54]

A solution to the bias inherent in the scheme would be to

remove the age limit for the hiring credit, and this has been recommended by a

number of stakeholders.[55]

However, such a change would inevitably undercut the main objective of the

scheme; namely, the creation of new jobs for younger workers who would

otherwise struggle to gain employment and who are the most likely to suffer

from the scarring effects of unemployment.

While it argues for the retention of some targeting

towards young people (young people aged under 25 years who have been unemployed

six months or more), ACOSS has recommended that the hiring credit should also

be made available to all long-term unemployed job seekers (those unemployed for

12 months or more). Alternatively, it has suggested that the hiring credit

could be targeted at young people under the age of 35 years and unemployed for

six months or more, with existing wage subsidies being expanded through an

uncapped subsidy pool.[56]

Likelihood of JobMaker Hiring

Credit success

The hiring credit is intended to put businesses in a

position to hire additional young employees. A key issue determining whether or

not they are able to achieve this is if employers are able to pay wages before

they receive the subsidy or are uncertain if prospective employees will reach

the 20 hour benchmark.

Another important issue in determining the success or

otherwise of the JobMaker hiring credit has to do with the trade-off between

ensuring that additional jobs are being created (increasing administrative

requirements) and maximising take-up of the subsidy.

The ACCI has argued that the less onerous eligibility

criteria of the JobMaker Hiring Credit, when compared to the Youth Bonus wage

subsidy, should see stronger take up of the hiring credit.[57]

However, while the hiring credit may be relatively

appealing to large businesses, some smaller businesses may baulk at the

administrative requirements associated with the scheme.[58]

Judging by submissions to the inquiry on the Bill from the Council of Small

Business Organisations Australia (COSBOA) and the Institute of Public

Accountants (IPA), aspects of the scheme such as the quarterly reporting and

additionality requirements may deter some small businesses from taking up the

hiring incentive, without additional incentives.[59]

COSBOA claims that feedback from its member organisations:

… indicates that the Hiring Credit wage subsidies are

too low. Given the apparent complexity of the Hiring Credit administration

process, for small businesses in particular the subsidy amounts are

insufficient to motivate additional hiring. If the Government’s goal is

to motivate large-scale additional hiring by Australian businesses, to reduce

unemployment by 450,000, COSBOA believes the subsidy rates will need to be at

least 50% higher than the proposed amounts.[60]

ACOSS has proposed a potential means of both increasing

JobMaker Hiring Credit take-up and reducing administrative costs to businesses.

This would involve the use of a labour market intermediary (between employer

and employee) to ‘help improve the matching of prospective employees and

employers, offer any support required, and help preserve the integrity of the

scheme’.[61]

As ACOSS sees it, the use of intermediaries (such as jobactive employment

service providers) could provide the ‘best of both worlds’ by

combining ATO administration of the subsidy (including handling applications

from employers) and use of intermediary organisations to recruit people on

income support payments as potential employees and to offer any support needed

by employers or employees to improve the prospects of a successful

placement’.[62]

Concluding

comments

Young people are typically harder hit by economic

downturns than are mature age people, and the COVID-19-induced recession is no

exception.

In this context, it is clear that something needs to be

done to tackle the immediate problem of youth unemployment, and the possibility

that it may become long-term.

Wage subsidies can help to encourage the hiring of

disadvantaged job seekers by firms, but this is highly dependent on the state

of the economy and the design and execution of wage subsidy programs.

In the case of the JobMaker Hiring Credit, for which a key

objective is additionality, a balance needs to be struck between protecting

against worker substitution and ensuring that administrative requirements are

not so onerous as to discourage businesses from taking up credits.

To the extent that the JobMaker Hiring Credit scheme is

specifically targeted at young people, it will, by definition, disadvantage

older job seekers, to some extent.

A number of submissions to the inquiry into the Bill have

made suggestions and proposed changes that could enable the scheme to better

achieve its objectives and encourage employers to offer workers more hours.