Introductory Info

Date introduced: 27 August 2020

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Environment

Commencement: Schedules 1–4 and items 1, 2 and 4–10 of Schedule 5 commence the day after Royal Assent; item 3 of Schedule 5 commences immediately after item 11 of Schedule 3.

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose of the Bill

- The

Bill proposes to amend the Environment Protection and Biodiversity

Conservation Act 1999 (the EPBC Act) to expand and clarify

provisions which allow the Commonwealth to delegate environmental approval

powers to the states and territories through bilateral agreements (to create

‘single touch’ environmental approvals).

Background

- The

Bill is almost identical to a Bill introduced into Parliament in 2014, which

lacked sufficient support in the Senate and subsequently lapsed in 2016. That

Bill aimed to facilitate the Government’s ‘one-stop shop’

policy for environmental approvals (now referred to as ‘single

touch’ environmental approvals).

- The

Bill has been introduced during a ten year independent statutory review of the EPBC

Act. The review’s Interim Report was released in June 2020, with a

final report due in October 2020.

Key issues and stakeholder concerns

- Stakeholders,

including conservation groups and the Law Council of Australia, are concerned

that the Bill is being rushed through Parliament before finalisation of the independent

statutory review. They consider that the Bill should be referred to a Senate

Committee for inquiry.

- Environment

groups do not support the Bill as a result of a number of concerns including:

- the

Bill replicates a 2014 Bill and does not address key recommendations in the Interim

Report, including in particular the development of national environmental

standards prior to the delegation of approval powers to states and territories

- the

accreditation of state and territory approval processes may create greater

complexity

- the

Commonwealth should provide strong leadership on environmental matters,

particularly in relation to Australia’s obligations under international environmental

agreements

- the

Bill proposes to remove the restriction on approval bilateral agreements covering

actions involving coal seam gas development or large coal mining development

that are likely to have a significant impact on a water resource (known as the

‘water trigger’)

- state

and territory governments do not have sufficient resourcing, nor adequately

robust processes, to assess and approve projects that may significantly impact

on matters of national environmental significance

- state

and territory governments may have a conflict of interest in approving

developments in which they are involved or which they actively support.

- Industry

groups appear not to have directly commented on this Bill, but have for many

years called for measures to remedy duplication between the EPBC Act and

state and territory approval processes, which they consider causes additional

delays and costs for proponents of relevant projects. In responses to the EPBC

Act review’s Interim Report, many industry groups supported the Interim

Report’s recommendation for clear national environmental standards.

- A

report by the Australian National Audit Office in June 2020 found that the

administration of the EPBC Act by the Department has been ineffective, with

a large increase in delays in decision-making under the EPBC Act since

2014–15. It has been suggested that these delays are largely a result of staffing

and funding cuts in the Department administering the EPBC Act.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Environment

Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Amendment (Streamlining Environmental

Approvals) Bill 2020 (the Bill) is to amend the Environment

Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (the EPBC Act)

to expand and clarify provisions which allow the Commonwealth to delegate

environmental approval powers to the states and territories through bilateral

agreements

The Bill largely replicates the Environment

Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Amendment (Bilateral Agreement

Implementation) Bill 2014 (2014 Bill), which was introduced into Parliament

in 2014, but lapsed in 2016 at the prorogation of parliament for the federal

election in 2016.[1]

Structure and

overview of the Bill

The Bill has five Schedules:

- Schedule

1 proposes amendments to clarify that actions covered by approval bilateral

agreements do not need to be referred to the Commonwealth

- Schedule

2 contains amendments to enable the assessment and approval of actions to be

completed in certain situations, such as where a bilateral agreement with a state

or territory is suspended or cancelled

- Schedule

3 has two parts:

- Part

1 proposes to remove the restriction relating to the ‘water

trigger’ so that actions involving coal seam gas development or large

coal mining development that are likely to have a significant impact on a water

resource can be subject to an approval bilateral agreement and

- Part

2 would extend the types of authorisation processes that can be accredited by

approval bilateral agreements

- Schedule

4 contains amendments to enable states and territories to make changes to

management arrangements or authorisation processes without the need to amend an

approval bilateral agreement, where the Minister makes a determination and is

satisfied that change will not have a material adverse impact on a matter

protected under the EPBC Act, or on a person's ability to participate in

the authorisation process and

- Schedule

5 contains miscellaneous amendments, including to enable a broader range of entities

such as local governments to approve actions under approval bilateral agreements.

Background

The EPBC Act is currently administered by the

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (the Department).

The EPBC Act provides that certain actions

(including projects, developments, undertakings or activities)[2],

known as ‘controlled actions’, must be referred for environmental assessment

and approval by the Commonwealth Environment Minister. Under the EPBC Act,

a ‘controlled action’[3]

is an action that has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact on:

- a

‘matter of national environmental significance’[4]

- the

environment on Commonwealth land[5]

or

- the

environment, where the action is undertaken by the Commonwealth Government or a

Commonwealth agency.[6]

The current matters of ‘national environmental

significance’, which are largely based on Australia’s

responsibilities under international agreements dealing with environmental

protection, are set out in Part 3 of the EPBC Act as follows:

- world

heritage properties

- national

heritage places

- wetlands

of international importance

- listed

threatened species and ecological communities

- listed

migratory species

- Commonwealth

marine areas

- the

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park

- nuclear

actions (such as uranium mines) and

- water

resources in relation to large coal mining and coal seam gas developments

(known as the ‘water trigger’).[7]

A more detailed overview of the EPBC Act is

available in the Parliamentary Library’s Environment

Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: A Quick Guide.[8]

Environmental assessment processes

Actions that require approval under the EPBC Act

undergo an environmental assessment process, as set out in the EPBC Act,

and supplemented by the Environment Protection

and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000. A useful flowchart

of the environmental assessment process is available on the Department’s

website.[9]

There are three key stages to this process:

1.

Referral: A proposed action is first ‘referred’ by

the proponent to the Commonwealth Environment Minister for his or her decision

as to whether the action is a ‘controlled action’: that is, whether

it requires formal assessment and approval under the EPBC Act. This decision

is based on whether the proposed action is likely to have a significant impact

on one or more of the matters of national environmental significance (as listed

above) or on the environment if it involves Commonwealth land or a Commonwealth

agency. If approval is required, then the proposed action proceeds to the

assessment and approval stage.

2.

Assessment: The Minister (or his or her delegate) determines the

method of assessment for the controlled action, based on considerations set out

in the EPBC Act and Regulations. The assessment methods include: an

accredited assessment approach, assessment based on information contained in

the referral to the Commonwealth, assessment based on preliminary

documentation, a public environment report (PER), an environmental impact

statement (EIS) or a public inquiry. The appropriate assessment approach will

depend on a range of matters, such as the scale and nature of an action’s

impacts.

In practice, assessment

bilateral agreements are in place with all states and territories (as discussed

below). This means that many projects are assessed under accredited state or

territory processes, but the Commonwealth Environment Minister makes the final

decision as to whether or not to approve the action (and whether the approval

is subject to conditions).

3.

Approval: Once a project has been assessed, the Commonwealth

Environment Minister decides whether to approve an action under the EPBC Act,

and the conditions to attach to that approval.

Assessment and approval may also be required at the state

or territory level under relevant state or territory legislation. Some industry

groups argue this is unnecessary duplication which, in turn, results in

additional costs and delays for those projects.[10]

In an attempt to minimise this duplication, the EPBC Act allows the

Commonwealth to enter into bilateral agreements with the states and territories,

as discussed in the next section.

Bilateral agreements

Bilateral agreements are made under Part 5 of the EPBC

Act and enable the Commonwealth to accredit relevant state and territory

processes, to effectively delegate the assessment and/or approval of actions

which would otherwise require assessment and approval under the EPBC Act.

The aim is to minimise duplication in the assessment and approval process for

actions which require approval under both Commonwealth and state or territory

laws.

There are two types of bilateral agreements:

- assessment

bilateral agreements, made under subsection 47(1) of the EPBC Act, which

provide for a single assessment process by accrediting a state or territory

process to assess the environmental impacts of a proposed action.[11]

After assessment, the proposed action still requires two separate approval

decisions from the Commonwealth (under the EPBC Act) and relevant state

or territory frameworks

- approval

bilateral agreements, which can accredit the assessment and approval

process of a state or territory.[12]

A proposed action taken in accordance with a process accredited under an

approval bilateral agreement does not require approval by the Commonwealth

Minister.[13]

Approval bilateral agreements cannot currently cover projects involving the

water trigger.[14]

Assessment bilateral agreements have been made with all

states and territories.[15]

However, as discussed later in this Digest, state and territory approval

processes have not been accredited under approval bilateral agreements to date.[16]

Approval bilateral agreements—accreditation

thresholds

Under the EPBC Act, approval bilateral agreements may

declare that certain actions do not need approval from the Commonwealth

Environment if they are taken in accordance with either a ‘bilaterally

accredited management arrangement’ or a ‘bilaterally accredited

authorisation process’. Under section

29 of the EPBC Act, an action taken in accordance with an accredited

management arrangement or authorisation process under an approval bilateral

agreement will not require the approval of the Commonwealth Environment

Minister.

Section

46 of the EPBC Act is one of the key provisions relating to approval

bilateral agreements, and provides for the Commonwealth Environment Minister to

accredit a management arrangement or authorisation process of a state or

territory.

However, sections 50–54 of the EPBC Act also

contain a number of requirements which must be satisfied before approval

bilateral agreements can be entered into and/or before the Minister can

accredit a management arrangement or authorisation process under section 46.

So, the Minister must be satisfied that the bilateral agreement accords with

the objects of the EPBC Act (as set out in section 3 of the EPBC Act, these

include the principles of ecologically sustainable development along with the

precautionary principle).[17]

In addition, the Minister may only accredit a state or territory management

arrangement or an authorisation process if the Minister is satisfied that the relevant

arrangement or process:

- is

not inconsistent with Australia's obligations under the relevant international

agreement (such as the World Heritage Convention[18])

- will

promote the management of the protected areas in accordance with the Australian

World Heritage management principles, National Heritage management principles

or the Australian Ramsar management principles[19]

- promotes

the survival and/or enhances the conservation status of any relevant listed

threatened or migratory species[20]

and is not inconsistent with any relevant recovery plan or threat abatement

plan[21]

- provides

for adequate assessment of the impacts of the action on each matter of national

environmental significance protected under the EPBC Act[22]

and

- that

actions approved in accordance with an accredited management arrangement or

authorisation process will not have unacceptable or unsustainable impacts on

any of the matters protected by the EPBC Act.[23]

These threshold requirements are not changed by this Bill.

The Minister must table a copy of the relevant management

arrangement or authorisation process in Parliament prior to accreditation, and

the relevant accreditation is subject to disallowance by either House of

Parliament.[24]

This requirement also remains unchanged by this Bill.

History of approval bilateral

agreements

The EPBC Act has had provisions for both assessment

and approval bilateral agreements since it first came into force in 2000,

although they were one of the more controversial aspects of the EPBC Act

at the time of its original passage through Parliament.[25]

As outlined earlier, approval bilateral agreements have never been implemented.

In 2012, following the first ten year review of the EPBC

Act, the Labor Government signalled its preparedness to negotiate

the transfer of environmental approval powers to states and territories as part

of its response to the review.[26]

However, in December 2012, then Prime Minister Julia Gillard subsequently

indicated that more work was needed to progress such bilateral agreements to

ensure that high environmental standards would be consistently maintained

across all jurisdictions. The Prime Minister also reportedly said that it was

necessary for the Commonwealth to maintain powers over World Heritage,

Commonwealth waters and nuclear issues.[27]

She also expressed concern that there was too much variation between states:

“I became increasingly concerned we were on our way to

creating the regulatory equivalent of a Dalmatian dog,” she said. “For

businesses that would be the worst of all possible worlds. It would leave them

with more litigation. We would have projects that were identical around the

country subject to different treatment.”[28]

‘One-stop shop’ reforms[29]

Following a change of government at the 2013 federal

election, approval bilateral agreements were placed back on the agenda as part

of the Government’s ‘one-stop-shop’ policy of having a single

environmental assessment and approval process on matters of national

environmental significance.[30]

In October 2013, the Environment Minister, Greg Hunt,

announced that the Government had approved a framework consisting of a three

stage process for achieving a one-stop-shop to streamline environmental approvals.[31] First, a Memorandum of Understanding was

signed with each state and territory in December 2013.[32]

In December 2013, COAG also agreed to work to develop bilateral agreements for

‘one-stop-shops’ for environmental approvals in each state.[33]

The second stage involved new or revised assessment

bilateral agreements, which were in place with each state and territory by December

2014.[34]

The final stage involved agreement on bilateral approvals with ‘willing

states’ and, while draft approval bilateral agreements were published for

some states and territories in 2014–15, none were ever finalised.[35]

Notably, subsections 65(2) and (3) require the Minister to

review the operation of a bilateral agreement at least once every five years,

and to publish the report of that review in accordance with the Regulations

(which require publication in the Gazette and on the internet).[36]

As such, it appears that many of the current assessment bilateral agreements

are overdue for review.

In March 2014, the Commonwealth Government released a

policy document, Standards

for Accreditation of Environmental Approvals under the Environment Protection

and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, which sets out environmental

standards and considerations for accreditation of state and territory approval

processes through bilateral agreements.[37]

Bilateral Agreement Bill 2014

In May 2014, the Environment

Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Amendment (Bilateral Agreement

Implementation) Bill 2014 (the 2014 Bill) was introduced in Parliament to

amend the EPBC Act and aimed to ‘facilitate the efficient and

enduring implementation of the Australian government's one-stop shop reform for

environmental approvals’.[38]

That Bill was the subject of inquiry and report by the Senate Environment and

Communications Legislation Committee.[39]

Both ALP and Greens Senators issued dissenting reports and did not support the

Bill.[40]

As indicated earlier in this Digest, this current Bill largely

replicates that 2014 Bill. The 2014 Bill passed the House of Representatives in

June 2014, with some government amendments (which have been incorporated into

this Bill). However, the 2014 Bill never passed the Senate and lapsed in April

2016.[41]

Relevant reviews since the 2014

Bill

Since the 2014 Bill lapsed, there appears to have been

little progress on the development of approval bilateral agreements. However, a

number of reviews have expressed concerns about the administration and

implementation of the EPBC Act. This includes:

- in

2017, an independent review of the water trigger which found, among other

matters, that the trigger is an appropriate measure to address the regulatory

gap that was identified at the time of its enactment.[42]

Relevant aspects of this review are considered in the ‘Key issues and

provisions’ section of this Digest

- in

2018, a review to examine the impact of the EPBC Act on

agriculture and food production.[43]

This followed concerns reportedly being expressed by some farmers about

duplication and complexity under the EPBC Act.[44]

A final report

was released in June 2019 and found that the number of agricultural referrals

under the EPBC Act had been relatively low.[45]

Among other matters, the report found that the Department is

‘insufficiently resourced to enable timely, appropriate and effective

assistance to be provided to project proponents in the agriculture

sector’.[46]

The report made 22 recommendations which it considered would ‘improve

harmonisation between state and territory and Australian Government

legislation’[47]

- in

2019, a Senate Committee issued an Interim Report for its inquiry into

Australia’s faunal extinction crisis, which concluded that there are

‘serious questions about whether the EPBC Act is still

fit for purpose and is in fact achieving [its] objectives’.[48]

The majority report of the Committee recommended new legislation to replace

the EPBC Act as well as an independent Environment Protection

Agency (EPA) ‘with sufficient powers and funding to oversee compliance

with Australia's environmental laws’.[49]

Australian National Audit Office

(ANAO) report

On 25 June 2020, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO)

issued a report on the administration of referrals, assessments and approvals

of controlled actions under the EPBC Act.[50]

The report described the Department’s administration of the Act in this

area as ‘not effective’:

Referrals and assessments are not administered effectively or

efficiently. Regulation is not supported by appropriate systems and processes,

including an appropriate quality assurance framework. The department has not

implemented arrangements to measure or improve its efficiency.

The department is unable to demonstrate that conditions of

approval are appropriate. The implementation of conditions is not assessed with

rigour. The absence of effective monitoring, reporting and evaluation

arrangements limit the department’s ability to measure its contribution

to the objectives of the EPBC Act.[51]

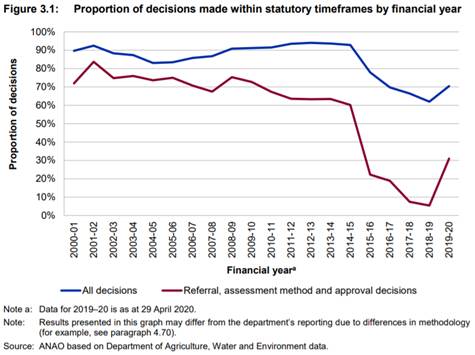

Among other matters, the report found compliance with

statutory timeframes has dropped significantly in recent years (see Figure below):

This decrease was most pronounced

from 2014–15 to 2018–19, with the proportion of referral, assessment

method and approval decisions made within statutory timeframes decreasing from

60 per cent in 2014–15 to five per cent in 2018–19. The average

time taken for approval decisions increased from 19 days over the statutory

timeframe in 2014–15 to 116 days over the statutory timeframe in

2018–19.[52]

Source:

ANAO, Referrals, assessments and approvals, op. cit., p. 51.

The report found that the ‘reasons for exceeding

statutory timeframes vary’ and may include:

… the department not considering that it has

satisfactory information to assess the proposed action, administrative delays,

disagreement between the department and the regulated entity over proposed

conditions, and delays in state or territory approvals where actions are also

subject to state or territory approval requirements. The department does not

systematically record or report on the reasons for delays.[53]

In this context, the Government provided $25 million over

two years to the Department in December 2019 for ‘Busting Congestion in

the Environmental Assessment Process’: that is to enable the Department ‘to

work through the backlog of environmental approval applications, with a focus

on major projects’.[54]

The Minister subsequently announced:

In the December quarter this year

just 19 per cent of key assessment decision points were being made on time.

By March 2020 we are making 87

per cent on time and the Department is on track to make that figure 100 per

cent by June 2020, with no relaxation of any environmental safeguards …

In December 19, there was also a

backlog of 78 overdue key decisions. That backlog has already been reduced by

47 per cent and is on track to be cleared by the end of this year.[55]

More recently, the 2020–21 Budget provided an

additional $36.6 million over two years from 2020–21 to ‘maintain

the timeliness of environmental assessments and undertake further reforms’

under the EPBC Act.[56]

This includes $12.4 million to ‘maintain the momentum’ established

through the $25 million provided in December 2019.[57]

However, some

commentators have suggested the increased delays in decision-making under

the EPBC Act are a result of reduced resources and staffing in the

Department, and any additional funding is ‘merely a reversal of previous

funding cuts’.[58]

EPBC Act review and Interim Report

The EPBC Act contains a statutory

requirement to review the operation of the Act every ten years.[59]

The last review (known as the ‘Hawke Review’) reported in

2009.[60]

The Government response to the review was released in 2011,[61]

although legislation to implement its recommendations was never introduced

prior to the change of government in 2013.

On 29 October 2019, the Minister announced the

commencement of the next independent statutory review, led by Professor Graeme

Samuel, to report to the Minister within 12 months.[62]

The review released a discussion paper

for public consultation in November 2019.[63]

Nearly 30,000 submissions were received, including more than 3,000

‘unique submissions’ and ‘around 26,000 largely identical contributions’.[64]

Following this consultation, the review released an Interim Report

on 20 July 2020 ‘to share and test thinking’.[65]

The Interim Report found the EPBC Act to be ‘ineffective and

inefficient’[66]

as it:

… does not enable the Commonwealth to play its role in

protecting and conserving environmental matters that are important for the

nation. It is not fit to address current or future environmental challenges.[67]

The Interim Report noted a ‘lack of trust’ in

the EPBC Act: the community does not trust the Act to deliver effective

protection of the environment, while industry views the Act as

‘cumbersome, duplicative and slow’.[68]

To build confidence, the Interim Report suggested that an ‘independent

cop on the beat is required to deliver rigorous, transparent compliance and

enforcement’.[69]

The Interim Report also found that ‘the EPBC Act had

failed to fulfil its objectives as they relate to Indigenous Australians’,

and recommended that:

The suite of national-level laws that protect Indigenous

cultural heritage in Australia needs comprehensive review. Cultural heritage

protections must work effectively with the development assessment and approval

processes of the EPBC Act.[70]

National Environmental Standards

The Interim Report suggested that ‘fundamental

reform is required’ and that ‘new, legally enforceable National

Environmental Standards should be the foundation’ of that reform.[71]

The report proposed that the Standards should be regulatory instruments which

set clear, strong, specific, measurable and granular rules which focus on

outcomes, not process.[72]

The report suggested that the Commonwealth should make these

standards ‘through a formal process set out in the EPBC Act’.[73]

Professor Samuel described the development of National Environmental Standards

as a ‘priority reform measure’.[74]

As a first step, the Interim Report suggested Interim standards be developed

‘to facilitate rapid reform and streamlining’.[75]

To this end, the Interim Report provided ‘prototype Standards’ for

matters of national environmental significance in Appendix 1 of the

report as a ‘starting point to stimulate discussion’:

The Review acknowledges that further work is needed to

test and refine the Standard. It is based on key principles such as

prevention of environmental harm and non-regression, and has been developed

using existing policy documents and legal requirements. The prototype shows

that an Interim National Environmental Standard for [Matters of National

Environmental Significance] could be developed quickly and would immediately

provide greater clarity and consistency for decision-making.[76]

[emphasis added]

Reducing duplication

The Interim Report found that there is duplication between

the EPBC Act and state and territory regulatory frameworks for

development assessment and approval, and efforts to harmonise and streamline

with these state and territory frameworks have not gone far enough.[77]

The Interim Report proposed that to remove duplication

between the EPBC Act and state and territory systems, decisions should

be devolved to other jurisdictions, where they demonstrate they can meet the

National Environmental Standards.[78]

The Interim Report further suggested that the ‘durability

of devolved decision-making’ should be improved.[79]

In this context, the Interim Report notes that the EPBC Act already

enables approval bilateral agreements to be entered into with states and

territories, but that approval bilateral agreements have never been

implemented.[80]

The Interim Report also refers to the unsuccessful amendments proposed by the

Commonwealth Government in 2014 which it suggests were designed to

‘provide a more enduring framework for devolution’.[81]

The report suggests that ‘important amendments are needed to’:

- enable

the Commonwealth to complete an assessment and approval if a state or territory

is unable to

- ensure

agreements can endure minor amendments to state and territory settings, rather

than requiring the bilateral agreement to be remade (and consequently be

subject to disallowance by the Australian Parliament on each occasion).

These and other necessary amendments have failed to garner

support in the Australian Parliament. In 2015 the Parliament did not support

these amendments, in response to significant community concerns about the

ability of states and territories to uphold the national interest when applying

discretion in approval decisions.[82]

At the same time, the Interim Report suggests that proposed

national environmental standards (discussed further below) should alleviate

some of the concerns that related to past legislation:

Previous attempts to devolve decision-making focused too

heavily on prescriptive processes and lacked clear expectations and thresholds

for protecting the environment in the national interest. The National

Environmental Standards proposed by this Review provide a legally binding

pathway for greater devolution, while ensuring the national interest is upheld.[83]

The report also recognised that the Commonwealth would

need to ‘retain its capability to conduct assessments and

approvals’ in certain circumstances, including:

… where the Commonwealth provides sole jurisdiction,

where accredited arrangements are not in place (or cannot be used), at the

request of a jurisdiction, or when the Commonwealth exercises its ability to

step in on national interest grounds.[84]

Interim Report proposed ‘phase

1 reforms’

Chapter 10 of

the Interim Report proposed a ‘reform pathway’, involving

‘three key phases’. The report suggested five areas of focus for the

first phase of reforms as follows:[85]

- reduce

points of clear duplication, inconsistencies, gaps and conflicts in the Act[86]

- issue

Interim National Environmental Standards to set clear national environmental

outcomes against which decisions are made

- improve

the durability of devolved decision-making, to deliver efficiencies in

development assessments and approvals, where other regulators can demonstrate

they can meet Interim National Environmental Standards

- implement

early steps and key foundations to improve trust and transparency in the Act,

including publishing all decision materials related to approval decisions and

- legislate

a complete set of monitoring, compliance, enforcement and assurance tools

across the Act.[87]

Other longer term reforms proposed in the Interim Report

are not discussed in this Digest in detail, but included, for example, the

establishment of a ‘properly resourced’ independent regulator and a

‘comprehensive redrafting of the EPBC Act’ to focus on outcomes

rather than process.[88]

Recent Government announcements

In a speech to a Committee for Economic Development of

Australia (CEDA) conference on 15 June 2020, the Prime Minister

flagged cutting approval times for big projects from the current 40 days to 30

days by the end of this year. He also announced a ‘priority list of 15

major projects that are on the fast-track for approval under a bilateral model

between the Commonwealth, states and territories’.[89]

The Departmental website states these 15 major projects

‘will be subject to the same requirements under the EPBC Act as

all referred projects’, but the ‘Australian Government will work

with the states and territories to establish joint assessment teams to progress

these projects’ to reduce duplication in assessment processes between the

two levels of government.[90]

On 20 July 2020, following the release of the EPBC Act review

Interim Report, the Minister for the Environment stated that the Commonwealth

will ‘prioritise the development of new national environmental standards,

further streamlining approval processes with State governments and national

engagement on Indigenous cultural heritage’.[91]

She further stated that the Commonwealth will ‘commit to the following

priority areas on the basis of the interim report’:

- Develop

Commonwealth led national environmental standards which will underpin new

bilateral agreements with State Governments.

- Commence

discussions with willing states to enter agreements for single touch approvals

(removing duplication by accrediting states to carry out environmental

assessments and approvals on the Commonwealth’s behalf).

- Commence

a national engagement process for modernising the protection of indigenous

cultural heritage, commencing with a round table meeting of state indigenous

and environment ministers …

- Explore

market based solutions for better habitat restoration that will significantly

improve environmental outcomes while providing greater certainty for business.

The Minister will establish an environmental markets expert advisory group.[92]

She also noted that the Commonwealth would ‘take

steps to strengthen compliance functions and ensure that all bilateral

agreements with States and Territories are subject to rigorous assurance monitoring’.[93]

However, at the same time, the Minister ruled out the establishment of an

independent regulator as well as any expansion of the EPBC Act in

relation to the regulation of greenhouse gas and other emissions.[94]

The Minister further noted that the Interim Report ‘raises

a range of other issues and reform directions’, which would be the

subject of further consultation.[95]

The Minister concluded that the Government would monitor the review’s

progress towards the final report, while continuing ‘to improve existing

processes as much as possible’.[96]

In a subsequent interview

on ABC radio on 21 July, the Minister indicated that the prototype environmental

standards would be part of the legislation to be introduced.[97]

She also stated that the Interim Report has ‘has made clear

recommendations that we can start to implement now’.[98]

On 24 July 2020, the Prime Minister announced that the new

National Cabinet had ‘agreed to move to single-touch environmental

approvals underpinned by national environmental standards for Commonwealth

environmental matters’:

Some states are able to transition to this system faster than

others. The Commonwealth will move immediately to enter into bilateral approval

agreements and interim standards with the states that are able to progress now.

We will simultaneously be developing formal national

standards through further public consultation. The National Cabinet also

endorsed the list of 15 major projects for which Commonwealth environmental

approvals will be fast-tracked.

For major projects at the start of the approvals process, we

will target a 50 per cent reduction in Commonwealth assessment and approval

times for major projects, from an average of 3.5 years to 21 months.[99]

On 7 August 2020, the Government published notices of

intention to develop draft approval bilateral agreements with all states and

territories.[100]

In welcoming the passage of the Bill through the House of

Representatives on 3 September,[101]

the Minister for the Environment stated that the amendments are:

… the start of a process that is entirely consistent

with Professor Graeme Samuel’s interim report and his findings in relation

to an Act that is long overdue for reform.

… There will be more reforms to follow. We will develop

strong Commonwealth-led national environmental standards which will underpin

new bilateral agreements with State Governments.[102]

Committee

consideration

The Senate Selection of Bills Committee considered the

Bill and was unable to reach agreement.[103]

A motion by Senator Hanson-Young to amend the Selection of Bills Committee report,

which would have referred the Bill to the Senate Environment and Communications

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 30 November 2020, was

unsuccessful.[104]

The Government did not support the motion, with Senator Cormann stating that

the Bill is ‘a carbon copy of a bill into which there has already been an

inquiry’.[105]

Subsequent motions by Senator Hanson-Young to refer the

Bill to the Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee for

inquiry and report were also unsuccessful.[106]

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Scrutiny of Bills Committee raised concerns in

relation to item 9 in Schedule 5, which inserts proposed section 48AA

into the EPBC Act to provide that a bilateral agreement may apply, adopt

or incorporate an instrument or other writing as in force or existing from time

to time, even if the instrument or other writing does not yet exist when the

agreement is entered into.[107]

The Explanatory Memorandum suggests this will ensure that

the operation of a bilateral agreement is preserved when instruments and policy

documents are updated, rather than requiring that the agreements are amended

each time an instrument or document that is referred to, applied, adopted or

incorporated in a bilateral agreement is updated.[108]

The Explanatory Memorandum further notes:

Bilateral agreements may make reference to a range of

Commonwealth, State or Territory instruments, policies or other documents

including, for example, significant impact guidelines and species survey

guidelines. State or Territories may also have policies that are specifically

relevant to their assessment and approval processes.

To ensure ongoing continuous improvement and to allow for the

maintenance of high standards for environmental approval, the Commonwealth or a

State or Territory may update or revise instruments and policies from time to

time. The application of the most current instruments and policies reflects the

importance of ensuring that environmental assessment and approval decisions are

based on the best scientific information available so that actions assessed and

approved by the State or Territory under the bilateral agreement will not have

unacceptable or unsustainable impacts on matters of national environmental

significance.[109]

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee noted this explanation,

but requested more detailed advice from the Minister as to:

… the type of documents that it is envisaged may be

applied, adopted or incorporated by reference under proposed section 48AA and,

in particular, whether these documents will be made freely available to all

persons interested in the law.[110]

In response, the Minister advised that the types of

documents that may be incorporated into bilateral agreements would include

Commonwealth legislative instruments and policies (such as threatened species

recovery plans), as well state or territory legislation, policies and plans.

The Committee welcomed the Minister’s advice that the relevant policies

and plans were expected to be made freely available, but noted there is no

requirement for such documents to be made freely available on the face of the

primary legislation. The Committee requested further advice from the Minister

as to whether the Bill could be amended to require that any document

incorporated into a bilateral agreement must be made freely available.[111]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

ALP Senators, along with Senators Griff, Lambie and

Patrick voted in favour of a Greens motion that there should be no debate on

the Bill until after the tabling of either the final report of the EPBC Act

review, or the Interim National Environmental Standards.[112]

The same Senators also voted in favour an unsuccessful motion to refer the Bill

to the Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee for inquiry

and report.[113]

ALP

The ALP does not support the Bill.[114]

The ALP’s Shadow Minister for the Environment and Water, Terri Butler,

has described the Bill as a ‘backwards-looking failed Abbott law rehash’.[115] Ms Butler noted that the Interim Report’s

proposals were ‘contingent on the creation of strong Interim National

Environmental Standards’. The ALP considers that the Government:

… should not pursue amendments until the interim

standards are finalised and made available to the people of Australia.

Without national environment standards recognised in law,

each state jurisdiction could negotiate different standards into each

agreement, which would increase job and investment delays and become a

regulatory nightmare. [116]

Ms Butler has suggested that the Government should introduce

strong national environmental standards, establish a genuinely independent

‘cop on the beat’ for Australia’s environment and, in light

of the recent ANAO report, fix the ‘delays caused by their massive

funding cuts’.[117]

The Greens

The Greens do not support the Bill. Leader of the Greens, Mr Adam Bandt, spoke against the

legislation in his second reading speech, suggesting:

… the federal government

is passing their responsibilities for protecting our environment onto the

states, where there are weaker laws and fewer environmental protections ... We

need more environmental protections, not less…. We need strong national

environmental standards and an independent regulator who can properly enforce

environmental protections.[118]

As noted in the ‘Committee consideration’

section of this Digest, Greens Senator Hanson-Young unsuccessfully moved

motions in the Senate to refer the Bill to the Environment and Communications

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report.[119]

In moving the first motion, Senator Hanson-Young suggested that ‘it is

absolutely essential’ to have ‘proper scrutiny of these

laws’, which she described as a ‘full-blown attack on Australia's

environment’. She also noted that the Bill ‘is effectively a carbon

copy of the legislation tabled by Tony Abbott in 2014, when Tony Abbott was

doing the bidding of big miners and big developers to strip environmental

protections’.[120]

Centre Alliance

Centre Alliance has stated that it cannot consider

supporting the Bill ‘until there is an inquiry into the legislation and

more certainty regarding the Government's promised National Environmental

Standards’. Ms Sharkie stated that Centre Alliance ‘supported

efficiency but not at the expense of less protection for the environment’.[121]

Senator Griff noted that he had voted in favour of an inquiry into the Bill,

and expressed frustration that ‘the Government is resisting an inquiry

into the Bill’ and that parliamentarians were being ‘asked to make

decisions without a thorough understanding of the effects these changes will

have’.[122]

Zali Steggall

Independent MP Ms Zali Steggall issued a

statement in response to the Interim Report, which among other matters, expressed

concern that the Government was rushing to devolve approvals and decision

making to the states, had ruled out establishing an ‘independent cop on

the beat’ to oversee the compliance and enforcement functions of the Act

and had announced ‘hurried legislative changes without establishing

strong Environmental Standards’.[123]

Ms Steggall subsequently tabled proposed

amendments in the House of Representatives to:

- remove

the amendments to allow approval bilateral agreements to cover actions under

the water trigger

- require

the Minister to make National Environmental Standards by legislative instrument

- provide

that the Minister may only enter into a bilateral agreement if the Minister is

satisfied that the agreement is consistent with those National Environmental

Standards and

- provide

that the Minister must not make certain decisions (as already listed in

subsection 391(3) of the EPBC Act) unless the Minister is satisfied the

decision is consistent with the National Environmental Standards.[124]

However, Ms Steggall’s amendments were not debated

or discussed in the House of Representatives and the Bill passed the House of

Representatives unamended.[125]

Helen Haines

Following the passage of the Bill in the House of

Representatives, Dr Helen Haines expressed concern that the Bill would

‘weaken our environmental laws’ and described the

Government’s approach to the House of Representatives debate as a

‘deplorable move’ and an ‘affront to our democracy’.[126]

Andrew Wilkie

Mr Andrew Wilkie MP described the Bill as ‘environmental

vandalism’ which ‘completely ignores’ Professor Samuel’s

interim recommendations to ‘accompany changes to the Act with stringent

national standards and an independent regulator’.[127]

He queried handing decision-making to state and territory governments who he

considers are ‘conflicted and incapable of protecting the environment’.

Mr Wilkie expressed particular concern about the Bill for Tasmania which he

suggested needs the protection of effective federal environmental legislation

‘now more than ever’ as a result of the Tasmanian Government’s

recent ‘Major

Projects’ legislation which he suggested will allow ‘dodgy

projects to be fast-tracked’.[128]

Senator Patrick

Senator Rex Patrick has indicated that he will not vote for

the Bill in the Senate at this stage.[129]

Senator Patrick has said the Bill needs to go to a Senate inquiry, reportedly

expressing concern about the lack of national standards, resourcing for states

and territories to deal with additional responsibilities and a lack of federal

oversight of a devolved approval process.[130]

Senator Lambie

Senator Jacqui Lambie has indicated that she wants to see

the final report of the EPBC Act review before making a decision.[131]

One Nation

At the time of writing, One Nation Senators do not appear

to have directly commented on the Bill.

Position of

major interest groups

Conservation groups

Conservation groups do not support the Bill. For example,

the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) described the Bill as a

‘backward step that would create a regulatory mess of accreditation with

no national standards embedded in law’.[132]

The ACF considered that the Bill ‘makes the EPBC Act more complex’

and ‘reduces oversight of important environmental matters’.[133]

ACF suggested:

National safeguards for our environment are important because

the federal government has responsibilities to protect nationally and

internationally recognised ecosystems like the Great Barrier Reef and Kakadu

and much-loved threatened wildlife like the koala.[134]

Similarly, the Wilderness Society noted that much of the

Bill is ‘word-for-word identical to Tony Abbott’s failed 2014 one-stop-shop

amendments’ and noted that it had been ‘expected that this Bill

would enshrine environmental standards before handing over powers to the

states, but again the promised protections have not been delivered.’[135]

The Society called on the Parliament ‘to resist the government’s

efforts to rush this bill through, and insist on a full package of reforms that

will ensure our environment laws are enforced and effective at turning around

Australia’s extinction crisis’.[136]

WWF-Australia has described the Bill as a ‘recipe

for extinction’, because it doesn’t address concerns raised in the

independent review of the EPBC Act. WWF-Australia expressed concern that

the Bill ‘would see federal approval powers handed over to states and

territories’, but ‘in its current form lacks standards to help

determine the strength of protection being afforded to nature, and lacks a

commitment to ensuring independent compliance’.[137]

The Environmental Defenders Office (EDO) has expressed

concern that the Bill is being ‘pushed through parliament’ before

the 10 year review of the EPBC Act is finalised. The EDO considers that

the Bill ‘fails to include key elements for reform suggested in Graeme

Samuel’s Interim Report’, including ‘no mention of national

environmental standards’ which is ‘a critical foundation of

reform’ nor of an independent compliance and enforcement regulator.[138]

The EDO has also released a report which audited state and territory

legislation and concluded that ‘no state or territory legislation met the

full suite of existing national environmental standards required to protect

matters of national environmental significance’.[139]

The Humane Society International has expressed concern

that the Bill hands over federal government responsibilities to states and

territories ‘who are ill equipped for the job, with no provision for

enforceable standards, no safeguards, no additional resources and no

independent regulator’.[140]

Birdlife Australia considers that the Bill weakens

‘our national nature laws’ and ‘breaks faith with submissions

from 30,000 Australians and the full findings of the EPBC review’.[141]

It suggested that ‘after the devastation of last summer's bushfires we

need stronger laws, not weaker ones, to better protect our natural heritage and

the unique and irreplaceable wildlife’.[142]

Several conservation groups have also written to the Director-General

of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO),

warning the international body of ‘alarming moves by the Australian

Government to weaken legal protection for Australia’s 20 World Heritage

listed properties’.[143]

The letter advises the UNESCO Director-General that the Morrison Government

‘is rushing a bill through the Australian Parliament that would hand its

national development approval powers’ to state and territory governments.[144]

Industry groups

At the time of writing, industry groups do not appear to

have directly commented on the Bill itself. However, as noted in the

‘Background’ section of this Digest, industry groups have for many

years been calling for reduced complexity and duplication between Commonwealth and

state and territory approval processes, which they consider causes additional

delays and costs for proponents of relevant projects. Several industry groups

have also welcomed and commented on the EPBC Act review Interim Report.[145]

For example, the Minerals Council of Australia (MCA) has

stated:

Reforms to the operation of the EPBC Act are needed to

address unnecessary duplication and complexity identified in the independent

review interim report. Reforms should provide greater certainty for businesses

and the community while achieving sound environmental outcomes.

…

The MCA supports the interim report recommendation to

establish national outcomes-based standards under the EPBC Act and devolution

of Commonwealth environmental assessment and approvals requirements to the

states and territories. The MCA also supports the commitment of national

cabinet to progress bilateral agreements between the Commonwealth and all

states and territories that would enable this devolution.

The MCA recommends the national standards and regulatory

architecture to support these agreements be carefully developed to ensure they

can be practically applied.[146]

At the same time, the Minerals Council has cautioned that

the department or body that has carriage of the assessment and approval

processes ‘must have the right amount of resources’.[147]

Similarly, the Australian Petroleum Production &

Exploration Association (APPEA) welcomed the report, including the recommendation

for consistent national environmental standards:

Overlapping requirements between states and the Commonwealth

and widespread duplication of processes between the Commonwealth and states do

not help to protect the environment but often causes unnecessary delays

increasing the costs for development.

… the report’s intention to establish clear

national environmental standards focused on outcome rather than process, will

provide greater flexibility when circumstances change while ensuring

environmental protection is maintained. [148]

The National Farmers’ Federation noted that it has

‘been seeking reform of the EPBC Act for more than a decade’ and

noted the Interim Report had made a number of ‘salient

recommendations’ including ‘that legally enforceable national

environmental standards be granular and focus on outcomes’ and ‘devolution

of assessments and approvals to willing states’.[149]

Law Council

The Law Council of Australia has suggested that the Bill

should ‘not be rushed through the Senate’ and has called for its

referral to a parliamentary inquiry.[150]

The Law Council reiterated its ‘longstanding view’ that ‘the

Commonwealth should be demonstrating leadership in biodiversity conservation

and environmental protection’. The Law Council stated:

Bilateral agreements should not operate without robust and

comprehensive Commonwealth oversight which is necessary to ensure that the

Australia’s obligations under international treaties are met and public

confidence and trust is maintained.[151]

The Law Council called for a ‘strong assurance

framework that clearly demonstrates how the Commonwealth Government will ensure

that its obligations under international law will be met’.[152]

The Law Council also considered that the independent inquiry should complete

its final report ‘before embarking on this significant change’.[153]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum:

… the Bill will not have direct financial impacts;

however, the reforms will result in regulatory savings for business, including

a reduction on administrative and delay costs associated with two separate

approval processes.[154]

The Minister has also reportedly indicated that the Bill

‘does not involve additional funding for the states’.[155]

However, the ACT Government has reportedly stated that it will be requesting

additional funding from the Commonwealth as part of bilateral agreement

negotiations because ‘additional work will need to be resourced if

responsibility for EPBC approvals is transferred’.[156]

The recent Commonwealth Budget included an additional $10.6

million over two years to progress negotiations with the states and territories

on bilateral agreements to accredit states to carry out environmental approvals

for Commonwealth matters.[157]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[158]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights had no

comment on the Bill.[159]

Key issues

and provisions

The Environment Minister has indicated that the Bill is:

… the first step towards implementing the national

cabinet decision of 24 July 2020, where all states and territories agreed in

principle to adopt reforms to move towards a single-touch approach to

environmental approvals.[160]

As noted earlier in this Digest, the EPBC Act

already contains provisions for approval bilateral agreements which allow the

Commonwealth to accredit state and territory approval processes. The Bill

proposes to amend related provisions in the EPBC Act to ensure

‘legally robust devolution of environmental approvals to the states and

territories’, with the aim of removing duplication with state and

territory processes.[161]

In her second reading speech, the Environment Minister suggested that this

duplication ‘adds unnecessary regulatory burden which delays job-creating

projects and impedes economic activity, and creates uncertainty around

environmental protections.’[162]

As noted earlier in this Digest, industry groups have for many years called for

measures to remedy duplication between the EPBC Act and state and

territory approval processes. However, conservation groups have expressed

concern about the Commonwealth devolving its responsibilities to the states and

territories and consider that the Commonwealth should provide strong leadership

on environmental matters, particularly in relation to Australia’s

obligations under international environmental agreements.

In her second reading speech, the Environment Minister

also described the Bill as ‘the first tranche of EPBC Act reforms linked

to the independent statutory review of the Act’.[163]

However, as discussed earlier in this Digest, several stakeholders, including

conservation groups and the Law Council of Australia, are concerned that the

Bill is being rushed through Parliament before finalisation of the independent

statutory review.[164]

They expressed concern that the Bill simply replicates a 2014 Bill and does not

address key recommendations in the Interim Report, particularly the development

of national environmental standards prior to the delegation of approval powers

to states and territories.[165]

As also noted earlier in this Digest, both environment and industry groups

supported the Interim Report’s recommendation for clear national

environmental standards.

In this context, the Department advised a Senate Committee

inquiry that it provided initial drafting instructions relating to the Bill to

the Office of Parliamentary Counsel on 19 June 2020, prior to the National

Cabinet decision on 24 July, and before the Interim Report of the EPBC Act review

was received by the Government on 30 June.[166]

Referrals

Currently, under section 68 of the EPBC Act, a

person proposing to take an action that the person thinks is, or may be, a

controlled action must refer the proposal to the Minister. As outlined earlier

in this Digest, a ‘controlled action’ is an action which will have,

or is likely to have, a significant impact on a matter of national

environmental significance.[167]

Once an action is referred, the Minister then makes a decision under the EPBC

Act as to whether or not approval is needed to take the action.[168]

Section 29 in Part 4 of the EPBC Act provides that

actions taken in accordance with an accredited management arrangement or

authorisation process under an approval bilateral agreement will not require

the approval of the Commonwealth Environment Minister. This effectively means

that actions covered by approval bilateral agreements in this way are not

‘controlled actions’ under the definition in section 67, because taking

the action without approval is not prohibited under the relevant provisions of

the EPBC Act.[169]

In turn, this means such actions do not need to be referred to the Minister.

The simplified outline in section 66 of the EPBC Act

confirms this by stating that actions covered by approval bilateral agreements

are not covered by Chapter 4 of the EPBC Act. Chapter 4 contains

provisions relating to the environmental assessment and approval process,

including the referral process.

However, as the Explanatory Memorandum states, ‘there

is currently nothing in the Act to prevent a person from referring an action to

the Minister’ that is otherwise covered by the scope of an approval

bilateral agreement, even though it is unnecessary.[170]

In particular, subsection 68(2) provides that a person proposing to take an

action that the person thinks is not a controlled action may still refer

the proposal to the Minister.

As such, the amendments in this Schedule aim to ‘reduce

duplication by clarifying the intended operation of the Act, as stated in

section 66’.[171]

Item 2 of Schedule 1 of the Bill inserts proposed

section 66A to clarify that proponents will not need, or be able, to refer

an action to the Commonwealth where the action is approved under an approval

bilateral agreement; or where an action is being, or will be, assessed under an

approval bilateral agreement and an approval decision has not yet been made in

accordance with that agreement.

Proposed subsection 66A(3) provides that if an

approval bilateral agreement is suspended generally or suspended in relation to

actions in a specified class and the proposed action falls into that class,

then the action may be referred to the Commonwealth Minister for the

Environment.

Where an action is to be taken in two or more states or

self-governing territories, proposed subsection 66A(4) provides that proposed

section 66A does not operate unless the section operates in each of

the relevant states or territories. In this case, the proposed action may be referred

to the Commonwealth.[172]

The remainder of items in Schedule 1 are consequential to proposed

section 66A.

Completing assessments

The amendments in Schedule 2 of the Bill aim to enable assessment

and approval of an action under the EPBC Act to be completed in certain

situations, such as where a bilateral agreement is suspended or cancelled,[173]

or where an approval bilateral agreement otherwise ceases to apply to a

particular action. In this context, the Explanatory Memorandum states:

It is expected that an approval bilateral agreement will

include provisions allowing the Minister, or a State or Territory Minister, to

declare that a particular action is no longer within a class of actions to

which the approval bilateral agreement relates. These provisions would operate

to allow the Minister to ‘call-in’ an action for assessment and/or

approval under the Act in circumstances where it is appropriate that the

Commonwealth approve the action. For example, the Minister may call-in an action

covered by an approval bilateral agreement if adequate environmental protection

is not being achieved.[174]

As outlined earlier in this Digest, the EPBC Act review

Interim Report identified amendments to enable the Commonwealth to complete an

assessment and approval if a state or territory is unable to as one of the

‘important amendments’ needed to provide a ‘more enduring

framework for devolution’ of Commonwealth approval powers to states and

territories.[175]

Deemed referrals

Item 3 of Schedule 2 inserts proposed section 69A

which provides for ‘deemed referrals’. Proposed section 69A

applies where the Commonwealth Environment Minister,[176]

or the relevant state or territory minister, makes a declaration under an

approval bilateral agreement that a specified action is no longer covered by

the agreement (an ‘exclusion declaration’). If an exclusion

declaration is made, then the person proposing to take the action is deemed to

have referred the proposal to the Commonwealth Environment Minister at the time

the exclusion declaration is made.

Proposed subsection 69A(4) and section 69B modify

certain requirements relating to the referral, including the publication and

consultation requirements, as follows:

- the

person taken to have referred the action does not have to state whether they

think that an action is a controlled action (proposed subsection 69A(4))

- the

requirements in section 72 about the way in which a referral must be made, and

the information a referral must include, will not apply (proposed subsection

69A(4))

- the

requirement for the Commonwealth Environment Minister to invite comments from

other Commonwealth Ministers or the appropriate state or territory minister

under subsections 74(1) and 74(2) will be discretionary (proposed paragraph

69B(a))

- the

Commonwealth Environment Minister will only be required to publish the

exclusion declaration, rather than the referral itself (proposed paragraph

69B(b)) and

- unlike

the requirements for other referrals,[177]

the Commonwealth Environment Minister will not be required to invite public comments

on whether an action to which an exclusion declaration relates is a controlled

action, although the Minister will have a discretion as to whether to invite such

comments (proposed paragraph 69B(b)). The Explanatory Memorandum

suggests that ‘providing the Minister with this discretion will avoid

duplicating processes that may have already been undertaken’ by a state

or territory.[178]

However, the Minister can decide not to invite comments on the referral, even

where a state or territory has not undertaken any consultation.

Partially completed state or

territory assessments

Currently, if the Minister has decided under the EPBC

Act that an action is a ‘controlled action’, then that action

is assessed under Part 8 of the EPBC Act (unless it is covered by an

assessment bilateral agreement). The Commonwealth Environment Minister decides

on the appropriate level of assessment for that action under section 87 of the EPBC

Act.[179]

Subsection 87(3) currently sets out a range of matters

that the Minister must consider when making this assessment approach decision. Item

6 of Schedule 2 inserts proposed paragraph 87(3)(ca) to include an

additional matter for the Minister to consider in situations where an action is

deemed to have been referred to the Commonwealth (under proposed subsection

69A(2)), or if a bilateral agreement is suspended or cancelled, and a state

or territory has partially completed an assessment of the relevant impacts of

the action. In these circumstances, the Minister must consider the extent to

which a partially completed assessment of the action by the state or territory

can be used, and the assessment completed, under the EPBC Act.

If a state or territory has partially completed an

assessment of the relevant impacts of an action, and the Minister decides to

complete that assessment under the EPBC Act, item 9 inserts proposed

subsection 87(7) to require the Minister to make a determination on:

- which

steps of the state or territory assessment process are to be used for the

purposes of assessing the relevant impacts of the action and

- the

remaining steps to be carried out to complete the assessment.[180]

The Explanatory Memorandum states that these provisions

are needed because state and territory assessment processes will differ, and

may not necessarily align with the steps under the various assessment

approaches under Part 8 of the EPBC Act.[181]

The Minister is required to publish a notice of his or her

decision on the assessment approach under section 91 of the EPBC Act. Item

11 inserts proposed subsection 91(3) to clarify that if the Minister

makes a determination under proposed subsection 87(7), the assessment

approach decision notice under section 91 must also specify which steps of the state

or territory assessment process are to be used and which steps are to be

carried out under a Part 8 assessment process.

One of the assessment approaches provided for in the EPBC

Act is an ‘accredited assessment process’, which enables

case-by-case accreditation of a Commonwealth, state or territory assessment

process. This can already be used in situations where, for example, a bilateral

agreement is not in operation in a state or territory, or an action is not

covered by a bilateral agreement. Subsection 87(4) sets out the matters that

the Minister must be satisfied of before deciding on an assessment by an

accredited process. However, currently, accreditation of a Commonwealth, state

or territory assessment process can only occur where the assessment has not yet

commenced. Items 7 and 8 of Schedule 2 amend paragraphs 87(4)(a) and

87(4)(c) respectively to provide the Minister with the option of deciding that

the assessment approach that will be used for a particular action will be an

‘accredited assessment process’ where part or all of that assessment

has already been completed. The Explanatory Memorandum notes:

To make the decision, the Minister will need to be satisfied

that the process has been, or is being, carried out under a law of the

Commonwealth, a State or self-governing Territory, and that there has been, or

will be, an adequate assessment of the relevant impacts of the action under the

process.[182]

Declaring a state or territory

assessment as an assessment

Item 10 of Schedule 2 inserts proposed sections

87A and 87B into the EPBC Act.

Proposed section 87A enables the Commonwealth Minister

to make a determination that an assessment by the state or territory under a

bilateral agreement is an assessment for the purposes of the EPBC Act in

certain situations. That is, where an action has been deemed to have been

referred under proposed subsection 69A(2), the Minister has decided that the action

is a controlled action, and a state or territory has completed an assessment of

the impacts. This would allow the Minister to then make a decision on whether

or not to approve the action under the EPBC Act.[183]

Proposed section 87B similarly enables the Minister

to make a determination that an assessment by the state or territory under a

bilateral agreement is an assessment for the purposes of the EPBC Act,

in situations where the assessment bilateral agreement has been suspended or

cancelled but the action has not yet been approved by the state or territory.

Item 12 amends section 130 to set a 40 business day

timeframe within which the Minister must decide whether to approve the taking

of the action if the Minister has made a determination under proposed

sections 87A or 87B. This is broadly consistent with the other

decision-making timeframes currently set out in section 130.

Application of Schedule 2

amendments

Item 17 provides that the amendments in Schedule 2 will

apply to actions that:

- have

been assessed by a state or territory before the amendments commence

- are

being assessed by a state or territory on the day the amendments commence or

- will

be assessed by a state or territory on or after the day the amendments

commence.

Approval bilateral agreements and the

water trigger

The amendments in Part 1 of Schedule 3 of the Bill propose

to enable approval bilateral agreements to cover the water trigger under the EPBC

Act. Currently, sections 24D and 24E of the EPBC Act provide that

actions involving a coal seam gas development or a large coal mining development

require assessment and approval under the EPBC Act if they have, will

have, or are likely to have, a significant impact on water resources. As noted

earlier, this is also known as the ‘water trigger’.[184]

When this water trigger was added to the EPBC Act in

2013,[185]

Parliament agreed to amendments by Independent MP Tony Windsor which prevented approval

bilateral agreements from covering the water trigger: that is, the Commonwealth

could not give a state or territory responsibility for approving relevant developments

under the water trigger.[186]

As a result, the water trigger is the only matter of national environmental

significance that cannot currently be the subject of an approval bilateral

agreement.

Items 1 and 2 of Schedule 3 amend

subsections 29(1), 46(2) and 46(2A) to remove this restriction, which will allow

a bilateral agreement to declare that actions involving coal seam gas or large

coal mining developments which have, will have or are likely to have, a

significant impact on water resources are actions within a class of action that

do not require approval under the EPBC Act.[187]

Note that the Bill does not remove the water trigger

itself, but rather allows the Minister to devolve responsibility to states and territories

to make approval decisions relating to large coal mining and coal seam gas developments

that are likely to have a significant impact on a water resource.

The issues of the water trigger and approval bilateral

agreements were one of the more divisive aspects of the previous 2014 Bill.[188]

Industry groups have argued for some time that the water trigger duplicates

state-based water regulatory frameworks and should be removed altogether.[189]

In contrast, conservation organisations and others suggest the water trigger

should be expanded to other unconventional gas developments and oppose handing

over approval powers relating to the water trigger to the states and

territories.[190]

The 2017 review of the water trigger (mentioned in the

‘Background’ section of this Digest) found that ‘scope should

exist’ for approval bilateral agreements to include decisions under the water

trigger.[191]

To this end, the review recommended that:

… should governments wish to further pursue bilateral

approval agreements relating to the water trigger an independent and

transparent review be conducted, by a person or persons, acceptable to both the

Commonwealth and the states, to undertake an analysis of relevant state

regulatory systems, practice and policy. The purpose of the review would be to

identify and make recommendations for any changes necessary for each state