Introductory Info

Date introduced: 17 October 2019

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Youth and Sport

Commencement: The formal provisions of the Bill commence on Royal Assent. Parts 1 to 4 of Schedule 1 will commence on proclamation or six months after Royal Assent, whichever is the earlier. The commencement of Part 5 of Schedule 1 is contingent on the passage and commencement of the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment (Sport Integrity Australia) Bill 2019.The Bills Digest at

a glance

Purpose

The Bill will amend the Australian Sports

Anti-Doping Authority Act 2006 (ASADA Act) to:

- streamline the administrative phase of the statutory anti-doping

rule violation process by abolishing the Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel

(ADRVP) and the right to appeal to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT)

- remove the privilege against self-incrimination in relation to

disclosure notices

- lower the burden of proof threshold for the chief executive

officer of the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (ASADA CEO) to issue a

disclosure notice

- extend statutory protection against civil actions to National Sporting Organisations

(NSOs) in their exercise of anti-doping rule violation (ADVR) functions and

- facilitate better information sharing between the Australian

Sports Anti‑Doping Authority (ASADA) and NSOs through enhanced statutory

protections for information provided to an NSO by ASADA.

Committee consideration

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

asked the Minister to provide further detail about why lowering the current ‘reasonable

belief’ standard is necessary and any safeguards that will be in place to guard

against the unauthorised use or disclosure of personal information obtained

under a disclosure notice.

Key issues

The Report of the

Review of Australia’s Sports Integrity Arrangements (Wood Review)

found that the ADRV process is generally convoluted and confusing, too

bureaucratic, and involves an inordinate number of procedural steps. The Bill

streamlines the process for the issue of an ADRV by abolishing the ADRVP and

the right to appeal to the AAT. It appears that the athlete’s right to a fair

hearing and an effective remedy are preserved under the proposed process.

ASADA has power to issue a disclosure notice to compel

certain persons to attend for questioning and to produce documents and things.

Failure to comply carries a civil penalty. The Bill proposes amendments to the

penalty provisions that do not appear to comply with the Attorney-General’s

Department Guide to Framing Offences. The Bill proposes lowering the

threshold for the issue of a disclosure notice from ‘the CEO reasonably

believes that the person has information, documents or things that may be

relevant to the administration of the NAD scheme’ to ‘the CEO reasonably

suspects, etc.’

The ASADA Act currently provides a person does not

have to answer a question or give information if that might incriminate the

person or expose them to a penalty. The Bill proposes removing the privilege

against self-incrimination and replacing it with a protection against use of

the incriminating material in court proceedings. The need to remove the

privilege against incrimination is contested.

History of the Bill

The Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment (Enhancing Australia's Anti-Doping

Capability) Bill 2019 (the first Bill) was introduced into the Senate on

14 February 2019. Debate on the second reading was adjourned and the Bill

lapsed at the end of Parliament on 1 July 2019.[3]

A Bills Digest was prepared for the first Bill.[4]

The Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment (Enhancing Australia's Anti-Doping

Capability) Bill 2019 (the Bill) was introduced into the House of

Representatives on 17 October 2019.[5]

The Bill is in substantially the same terms as the first

Bill. The only changes are of a technical nature to improve the drafting.

However, since items 22, 23 and 25 of Part 1 in the first Bill have been moved

to Part 5 in the Bill, the item numbers throughout the Bill have changed. The

Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill has been extensively revised.

Structure of the Bill

The Bill has one schedule with five parts which amend the Australian Sports

Anti-Doping Authority Act 2006 (ASADA Act).

Part 1—Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel

- abolishes the Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel (ADRVP), streamlines

the anti-doping rule violation (ADRV) process and makes minor consequential

amendments to the Australian

Sports Commission Act 1989 (the ASC Act)

Part 2—Protection from civil actions

- extends protection to National Sporting Organisations (NSOs) and

personnel to encourage cooperation with the Australian Sports Anti‑Doping

Authority (ASADA)

Part 3—Disclosure to courts or tribunals

- protects information shared with key stakeholders from disclosure

in open court or tribunal proceedings

Part 4—Disclosure notices

- alters the statutory threshold for issuing disclosure notices

- alters the times and places a person is entitled to inspect

things produced under a disclosure notice

-

increases the penalty for non-compliance with a disclosure notice

- removes the remaining elements of the privilege against

self-incrimination when responding to a disclosure notice

Part 5—Contingent

amendments

- provides for different scenarios contingent on when the Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment (Sport Integrity Australia) Act 2019

(if it passes Parliament) commences.[6]

Purpose of the Bill

The purpose of the Bill is to amend the Australian Sports

Anti-Doping Authority Act 2006 (the ASADA

Act) to implement the recommendations of the Report of the Review of

Australia’s Sports Integrity Arrangements (Wood Review)[7]

to allow ASADA’s existing regulatory functions to be carried out more

effectively. The amendments include:

- streamlining the administrative phase of the statutory

anti-doping rule violation process by abolishing the ADRVP and the right to

appeal to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT)

- extending statutory protection against civil actions to NSOs in

their exercise of ADRV functions

- facilitating better information sharing between ASADA and NSOs

through enhancing statutory protections for information provided to an NSO by

ASADA

- lowering the burden of proof threshold for the chief executive

officer of the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (ASADA CEO) to issue a

disclosure notice and

- removing the privilege against self-incrimination in relation to

disclosure notices.

This Bill is one of four pieces of legislation that were

prepared to implement Stage One of the Safeguarding the Integrity of

Sport—the Government Response to the Wood Review (Government Response).[8]

The other three are:

Background

Sport is now a major industry,

estimated to account for between three per cent and six per cent of world

trade.[9]

The commercialisation of the sporting environment together with the increasing

product value and the social and cultural importance of high-profile sport has

led to a growing need to protect the integrity of sporting competitions. ADRVs

can have profound consequences for the athlete, support person, club and sport.

It is, therefore, important that there are mechanisms for swift and fair

resolution of ADRV disputes.

The World Anti-Doping Code

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) was established in

late 1999 to promote and coordinate the fight

against doping in sport internationally.[10] WADA developed the World

Anti-Doping Code 2015 with 2019 amendments (the Code) which first came into force in 2004.[11]

In October 2005 the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO) adopted the International

Convention Against Doping in Sport.[12]

The Convention has been signed by 188 countries, including Australia.[13]

Parties to this Convention are required to implement the Code:[14]

[The Code] is the core document that harmonizes anti-doping

policies, rules and regulations within sport organizations and among public

authorities around the world.[15]

Australia’s National Anti-Doping Scheme

ASADA was established by the ASADA Act to assist

the CEO of ASADA perform functions including making, amending and administering

a national anti-doping scheme (NAD scheme) and other sports doping and safety

matters.[16]

The NAD scheme is made and administered by the ASADA CEO under authority of the

ASADA Act. The NAD scheme is contained in Schedule 1 of the Australian Sports

Anti-Doping Authority Regulations 2006 (ASADA Regs).

The ASADA Act also

creates the ADRVP[17]

and the Australian Sports Drug Medical Advisory Committee (ASDMAC).[18]

The ADRVP has various functions, including those conferred by the NAD scheme.[19]

Currently the NAD scheme provides that the ADVRP’s functions include satisfying

themselves that there has been an ADRV and requesting the ASADA CEO to issue an

infraction notice.[20]

The provisions of the Code, the NAD scheme and the

ASADA approved anti-doping policies of sporting bodies, have a substantive

effect on how ADRVs are investigated, asserted, contested and punished. It is

important to consider the entire scheme to properly understand how a suspected

ADRV will be dealt with.

The ASADA

Act requires that the NAD scheme implement Australia’s international

anti-doping obligations.[21]

Division 2 of Part 2 of the ASADA Act

requires prescribed matters to be included in the NAD scheme. The proposed

amendments in Part 1 make changes to the

requirements for the NAD scheme, rather than to the NAD scheme itself.

Therefore the Bill will require consequential amendments be made to the ASADA

Regs.

Division 2.1 of the NAD Scheme sets out the anti-doping

rules, which are the same as the ten ADRVs listed in Article 2 of the Code.

(Set out in Table 1 below).

Table 1: ADRVs and

prescribed sanctions

NAD Scheme

anti-doping rule

|

Sanction in Code

for violation of rule

|

|

2.01A Presence in athlete's

sample of prohibited substance, or metabolites or markers. (Code

article 2.1)

Offence is absolute liability—clause 2.01A(3).[22]

|

(Code article 10.2.1) Ineligibility[23]

for 4 years if:

- ADRV did not involve a specified substance—article 10.2.1.1 or

- ADRV involved a specified substance and was

intentional—article 10.2.1.2

(Code article 10.2.2) Ineligibility for 2 years

if:

- ADRV did not involve a specified substance and person

can prove was not intentional or

- ADRV involved a specified substance but there is no proof

violation was intentional

|

|

2.01B Use or attempted

use by an athlete of a prohibited substance or a prohibited method. (Code

article 2.2)

Offence is absolute liability—clause 2.01B(2).

|

|

2.01C Evading,

refusing or failing to submit to sample collection

(Code article 2.3)

|

Ineligibility for 4 years OR 2 years if person can

prove ADRV was not intentional—article 10.3.1.

|

|

2.01D Whereabouts

failures

(Code article 2.4)

|

Ineligibility for a usual period of 2 years reducible to a

minimum of 1 year depending on athlete’s degree of fault—article 10.3.2.

|

|

2.01E Tampering or

attempted tampering with any part of doping control

(Code article 2.5)

|

Ineligibility for 4 years OR 2 years if person can

prove ADRV was not intentional—article 10.3.1.

|

|

2.01F Possession of

prohibited substances and prohibited methods

(Code article 2.6)

|

(Code article 10.2.1) Ineligibility[24]

for 4 years if:

- ADRV did not involve a specified substance—article 10.2.1.1 or

- ADRV involved a specified substance and was

intentional—article 10.2.1.2

(Code article 10.2.2) Ineligibility for 2 years

if:

- ADRV did not involve a specified substance and person

can prove was not intentional or

- ADRV involved a specified substance but there is no proof

violation was intentional

|

|

2.01G Trafficking or

attempted trafficking in a prohibited substance or prohibited method

(Code article 2.7)

|

Ineligibility for a minimum of 4 years up to lifetime

depending on seriousness of violation. If substance trafficked to a minor by

a support person, lifetime ineligibility. Conduct reported to judicial

bodies—article 10.3.3.

|

|

2.01H Administration

or attempted administration of a prohibited substance or prohibited method

(Code article 2.8)

|

Ineligibility for a minimum of 4 years up to lifetime

depending on seriousness of violation. If substance administered to a minor

by a support person, lifetime ineligibility. Conduct reported to judicial

bodies—article 10.3.3.

|

|

2.01J Complicity (Code

article 2.9)

|

Ineligibility for a minimum of 2 years up to 4 years

depending on seriousness of violation—article 10.3.4.

|

|

2.01K Prohibited

association

(Code article 2.10)

|

Ineligibility for a usual period of 2 years reducible to a

minimum of 1 year depending on person’s degree of fault—article 10.3.5.

|

Source: Parliamentary Library

For some ADRVs, the sanction

provides some latitude as to period of ineligibility and the tribunal will have

to apply discretion. Some sanctions are mandatory. In addition to the sanctions

listed in Table 1 above, Article 9 of the Code provides that an

in-competition ADRV will automatically result in a disqualification from

results in that competition including forfeiture of any medals, points and

prizes. Individual prizes in some sports competitions exceed one million

dollars.

The personal consequences of an ADRV determination for a

professional athlete, coach or medical support person can be very grave. The

reputational damage alone can be career ending. A multi-year period of

ineligibility to participate can also result in the loss of substantial

sponsorship income or effectively end an athletic career.

Contractual binding of athletes and support persons

to the Code

Australian sport bodies are subject to what has been

called ‘soft’ coercion to adopt key national policies for sports integrity.[25]

The Wood Review noted:

The anti-doping framework, both domestically and

internationally, is highly complex; it involves national and international

governance, private corporations and NGOs in a complicated web of contractual

agreements, private arbitration and government regulation which operates both

coercively and by way of moral imperative and reputational protectionism.[26]

The coercion operates in a variety of non-statutory ways:

- in order for athletes to compete at international level, the NSO

must join or affiliate with the international sporting organisation and

implement its sports integrity policies (which in practice means implementing

the Code)[27]

- to be eligible for Commonwealth government funding, a sporting

organisation must be recognised as an NSO by Sport Australia[28]

- to be recognised as an NSO, the organisation must meet certain

criteria including:

The organisation is accountable at the national level for

establishing and enforcing the key policies that underpin integrity in their

sport, including

- A

current policy for harassment, discrimination, bullying, abuse, child safe and

complaints that at a minimum are consistent with Sport Australia policy

templates; and

- A

current anti-doping policy compliant with the World Anti-Doping Code and

approved by the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (ASADA) ...[29]

Sport law academics have observed:

One of the intriguing effects of the [Code] and the

NAD scheme is the inclusion of Australian sports that are neither Olympic nor

international into an international anti-doping regimen. The same observation

can be made in respect to athletes who are ‘merely club-players’.[30]

The funding requirements of Sport Australia are

underpinned by clause 2.04 of the NAD scheme which requires a ‘sporting

administration body’—which is defined as a NSO for Australia NSO—to have in

place an anti-doping policy that complies with the mandatory provisions of the Code.[31]

The NAD scheme requires that the anti-doping policy is approved by the ASADA

CEO.[32]

Further influence is exerted when NSOs organise national

competition. For example, the NSO may prescribe that athletes must be members

of the NSO or of affiliated state or local bodies to be eligible to compete at

national level. The state or local bodies must comply with the NSO anti-doping

policy in order to affiliate or join.[33]

To assist the NSOs to draft compliant anti-doping

policies, ASADA distributes a template anti-doping policy.[34]

Self-incrimination provisions that have been included in that template, and the

lawfulness of their inclusion, are discussed further below.

The Wood Review noted:

Anti-doping arrangements operate fundamentally on a ‘sport

runs sport’ basis, with the adoption of Code-compliant anti-doping

policies being a precondition for continued international recognition and

government support.

In Australia, this manifests in NSOs developing and

implementing Code-compliant, ASADA-approved policies; committing their

athletes and support persons, through contractual arrangements, to abide by

these policies; working with ASADA as the Australian NADO [National Anti-Doping

Organisation] to implement effective anti-doping activities; and, through

referral of ADRVP assertions from ASADA, being responsible for making the final

decision on possible ADRVs. [35]

Acceptance of the often onerous terms of anti-doping

policies compliant with the Code is characterised as a voluntary contractual

choice.[36]

However, sporting bodies, athletes and support persons are, in practice, compelled

by a succession of WADA, Commonwealth, ASADA and NSO policies to comply with these

anti-doping policies in order to participate in sports.[37]

Current process for investigation and determination

of an ADRV

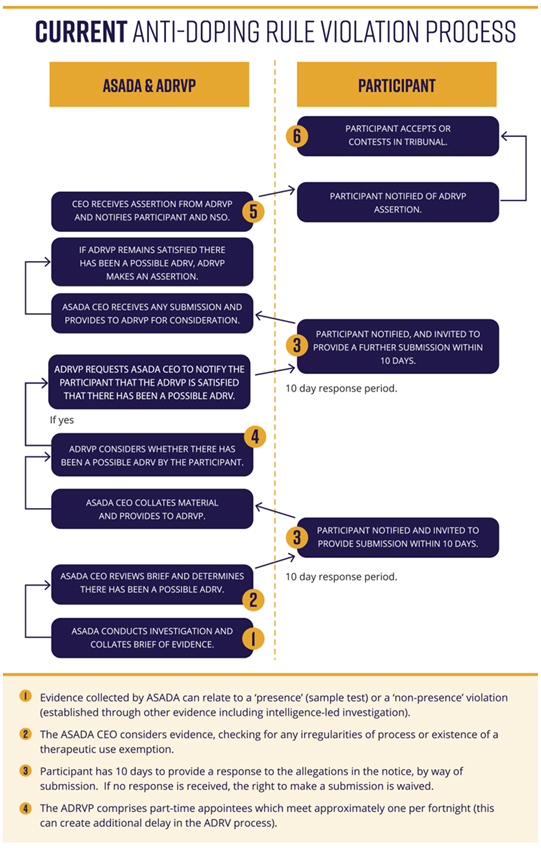

There are four stages an ADRV goes through to final

determination. The first stage is an investigation by the ASADA CEO. The second

stage is the process for the ASADA CEO to issue notice of an ADRV. During this

process the person suspected of an ADRV can make submissions to the ASADA CEO

and the ADRVP. Once the ADRV notice is issued, the person may make an

application for arbitration. The fourth stage is the arbitration hearing. Flowchart 1

below shows the process visually.

Stage 1: ASADA CEO conducts an investigation

ASADA CEO’s coercive investigatory powers

It is the NAD scheme which authorises the ASADA CEO to

conduct investigations into suspected ADRVs and to issue ADRV notices. When a

doping incident is suspected, ASADA investigates and provides a brief of

evidence to the ASADA CEO.

Section 13A of the ASADA Act

and clause 3.26B of the NAD scheme authorise the ASADA CEO to give a

person a disclosure notice requiring the person to:

- attend an interview to answer questions

- give information of the kind specified in the notice

- produce documents or things of the kind specified in the notice.

At the moment, the CEO can only give the notice if the

CEO reasonably believes that the person has information, documents or

things that may be relevant to the administration of the NAD scheme and

three members of the ADRVP agree that the CEO’s belief is reasonable.

Any person can be compelled to attend an interview—they do

not have to be suspected of wrongdoing. The only requirement is that they may

have relevant information. Potential witnesses and third parties can be

compelled to attend interviews or provide documents.

Flowchart

1: current ADRV process

Source: Wood et al., Wood Review, op. cit., p. 136

Privilege against self-incrimination during

investigation

The common law privilege against self-incrimination is an

absolute right that can only be abrogated by statute or waived by consent. Prior

to August 2013, the ASADA Act contained no provisions authorising

compulsory questioning or abrogating the privilege. In 2013, Senator Kate

Lundy, stated in her second reading speech introducing the Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment Bill 2013 (2013 ASADA Bill):

I have also asked ASADA and the National Integrity in Sport

Unit within the Office for Sport to work with our national sporting

organisations to amend their Codes of Conduct and/or anti-doping policies so

that all athletes and their support personnel are required to cooperate with an

ASADA investigation. National sporting organisations will be required to apply

an appropriately strong sanction (such as significant periods of ineligibility)

for those who fail to do so.[38]

The 2013 ASADA Bill contained proposed provisions

supporting that Ministerial policy; however, the Bill was amended in the Senate

to insert subsection 13D(1) into the ASADA Act.

Subsection 13D(1) provides that, during an investigation, a natural person (not

a corporation) does not have to answer a question or give information if that

might incriminate the person or expose them to a penalty.[39]

That statutory protection is currently undermined,

however, by the terms of the ASADA approved anti-doping policies incorporated

into the membership rules of sporting bodies and into athlete contracts.[40]

For example, the Anti-Doping Policy of the Australian Sports Commission

(ASC), [41] which covers athletes and

support persons at the Australian Institute of Sport, states:

The clause in the anti-doping policy abrogating the

privilege against self-incrimination and self-exposure to a penalty is not

required by the Code or the NAD scheme and is in direct conflict with the

protection provided by Parliament in subsection 13D(1) of the ASADA Act.

Anti-doping policies such as these are incorporated in

conditions of membership or athlete and support person contracts, so joining a

sporting organisation or accepting an employment contract may involve a waiver

of the privilege against self-incrimination that the person may not be aware

has occurred.

Legal constraints on Commonwealth agencies and public

officers

Parties to a contract are free to decide the terms of

their contract; however, Commonwealth officers and agencies have additional

obligations imposed by the duties of their office. It is a fundamental principle

of constitutional law that powers and discretions granted by statute are restrained

by the terms of the statute. The rule of law, supported by section 75(v) of the

Australian

Constitution, requires respect by Commonwealth officials for the limits

of power and official compliance with their legal duties.[42]

It would be a straightforward breach of the ultra vires

doctrine for a Minister, other public officer, or Commonwealth agency to take

deliberate action which had the purpose or effect of avoiding a statutory

requirement or otherwise breaching the duties and obligations of the office or

agency. Such action would be beyond the lawful authority of the officer or

agency and would expose them to civil and, in some circumstances, criminal

liability.[43]

The question whether ASADA acted lawfully in obtaining

evidence as a result of the contractual waiver of the privilege against

self-incrimination was specifically considered and extensively examined in Essendon

Football Club v CEO ASADA (the Essendon FC case).[44]

In that case, the Essendon FC coach and players had contractually waived their

privilege against self-incrimination if questioned by officers of the

Australian Football League (AFL). The AFL chose to interview the coach and

players in the presence of ASADA personnel. Critically, no claim to the

privilege against self-incrimination was made by the coach or players at the

interviews.

The provisions of the ASADA Act at that time did

not allow ASADA to issue disclosure notices, so any conflict with the

requirements of subsection 13D(1) did not arise. Middleton J found:

The use of the compulsory powers by the AFL (and not by

ASADA) did not thwart or frustrate the purpose of the Act or the NAD Scheme. ASADA

did not use any compulsory power of its own, and Mr Hird and the 34 Players did

not answer questions or provide any information arising from any requirement to

do so under or pursuant to the Act or NAD Scheme. No power of the State has

been utilised by ASADA to compel Mr Hird or the 34 Players to act in the way

they did during the investigation.

I should indicate that even after the introduction of the

2013 Amendment Act, the position did not change in respect of Mr Hird and the

34 Players, who remained subject to the contractual regime. ASADA may need to

rely upon the Act as amended to facilitate obtaining information from persons

outside that contractual regime. However, nothing in the amended Act added

to or removed the ability of ASADA to request the voluntary provision of

information from the AFL, or from those who voluntarily contracted to

provide information to the AFL (and to ASADA).

I have already considered the nature of privilege against

self-incrimination, and how it was effectively curtailed under the contractual

regime entered into by Mr Hird and the 34 Players. At the interviews, no claim

to invoke the privilege against self-incrimination was made. Mr Hird and

Essendon had the opportunity to refuse to answer questions and provide

information, albeit with the consequence of possible contractual sanctions by

the AFL. No power of the State would have been involved in the imposition of

this sanction—ASADA could take no action to enforce the refusal of any player

or of Mr Hird to answer questions or provide information. This would be

entirely a matter for the AFL. In essence, there was thus no “compulsion” by

ASADA at all, nor any resultant abrogation of privilege against

self-incrimination.[45]

Middleton J left open the question of whether, if ASADA

had used its own power to compel the players to give answers which would

incriminate them, that would have thwarted or frustrated the Act. The question

of whether the use of a disclosure notice by ASADA to compulsorily access

evidence would conflict with the current provisions of the ASADA Act or

the NAD scheme was not considered by Middleton J because:

- ASADA did not issue a disclosure notice and

- the disclosure of evidence to ASADA by the players and coach was ruled

voluntary since no claim to invoke the privilege of self-incrimination was

made.

The question has therefore not been determined.

The proposal in the Bill to legislatively abrogate the

privilege against self-incrimination is discussed further below in ‘Key

issues and provisions’ under the heading ‘Removing self-incrimination as a

defence to answering questions’.

Stage 2: Issue of the

ADRV notice

If the ASADA CEO believes there is a possible ADRV, the

ASADA CEO notifies the athlete or support person and gives them ten days to

make a submission. The ASADA CEO collates the material and passes it to the

ADRVP.[46]

If the ADRVP is satisfied that there has been a possible

ADRV, the ASADA CEO notifies the athlete or support person and gives them ten

days to make a submission to the ADRVP.[47]

If, after considering the submission, the ADRVP is still satisfied there has

been a rule violation, it asserts the ADRV and authorises the ASADA CEO to give

notice of the ADRVP’s decision to the athlete or support person.[48]

The athlete or support person then either accepts the ADRV

notice or contests it in a tribunal. If they take no action, they are deemed to

accept the ADRV notice.

Stage 3: The person

issued the notice applies for arbitration

Private arbitration, the resolution

of sporting disputes by and through the rules of the sport, is ‘now firmly

established as the dispute resolution method of choice throughout the sports

industry’.[49]

One reason for the choice of arbitration is that, as the Wood Review put

it:

... maintaining organisational autonomy is a high priority for

national and international sporting organisations ...

... sport runs sport, setting the rules for administration,

competition and governance, including rules regarding integrity issues at

international and national levels.[50]

Current ASADA approved anti-doping policies specify that

the hearing will be conducted by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) (or

an in-house tribunal); the National Sport Tribunal (NST) Anti-Doping Division is

intended to be the default arbitration tribunal in the future.[51]

Stage 4: The arbitration

hearing

The determination the tribunal must make

The finding the arbitration tribunal needs to make, and

the burden and standard of proof for that finding, are contained in the

anti-doping policy of the relevant sporting body. The need for approval by

ASADA should ensure they reflect the Code. For example, the Code

provisions are mirrored in the ASC Anti-Doping Policy:

The standard and burden of proof

are prescribed by Article 3 of the Code and mirrored in approved

anti-doping policies:

The NAD scheme in rules 1.02A(3)

and 4.13, and the approved anti-doping policies, make clear the function of the

ASADA CEO in the hearing is analogous to a prosecutor:

If the first instance hearing

tribunal finds that the person has committed an ADRV, the tribunal will be

required by the anti-doping policy to apply the sanctions prescribed in Article

10 of the Code (set out in Table 1 above).

The Wood Review

The Wood Review was a comprehensive examination of

sports integrity arrangements, set up by the Government ‘in response to the

growing global threat to the integrity of sport’.[56]

It considered issues around prevention, investigation, and administrative

responses to match fixing and doping. The Wood Review consulted widely

and made 52 recommendations.

The centrepiece of the Wood Review recommendations

is the formation of a National Sports Integrity Commission (NSIC) to manage

sports integrity matters at a national level. The Wood Review

recommended:

That the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (ASADA) be

retained as Australia’s National Anti- Doping Organisation and that the current

requirement for all National Sporting Organisations (NSO) (including sports

with competitions only up to the national level) to have anti-doping rules and

policies that comply with the World Anti-Doping Code also be retained.[57]

The Government did not support ASADA remaining an

independent organisation and Australia’s National Anti-Doping Organisation

(NADO). Instead, the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment (Sport

Integrity Australia) Bill 2019 proposes replacing ASADA with Sport Integrity

Australia (SIA).[58]

Stakeholders appear to support this approach (see discussion below).

This Bill is focused on the parts of the Wood

Review dealing with improving anti–doping measures. The most

relevant portion of the Wood Review to this Bill is Chapter 4: The

Capability of the Sports Anti-doping Authority and Australia’s Sports Sector to

Address Contemporary Doping Threats.[59]

Government response

The Government agreed with 22 of the Wood Review

recommendations, agreed in-principle with 12 and a further 15 were agreed

in-principle for further consideration. Two recommendations were agreed in part

and one was noted.[60]

The Government Response indicated that it

would take a phased approach: some of the important recommendations will be

implemented immediately while more complex recommendations will be further

considered and implemented at a later stage.[61]

This Bill is part of the first stage and implements Wood Review

recommendations 17, 19, 23 and 24 in part or in full.

A Wood Review recommendation that all NSOs continue

to comply with the Code was not supported by all sports and that

opposition is discussed below under the heading ‘Positions

of major interest groups’. However, the Government agreed with the Wood

Review that all NSOs should continue to have Code-compliant

anti-doping policies.[62]

Committee consideration

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

(Scrutiny of Bills Committee) reported two scrutiny concerns on the first Bill

in Scrutiny Digest 2 of 2019.[63]

Removal of merits review

The Committee noted its scrutiny concerns regarding the

proposal to remove review by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal of assertions

by the Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel in relation to potential anti-doping

rule violations (consequential on the abolition of the Panel). This issue is

discussed further below under the heading ‘Part 1—Abolishing the ADRVP and

appeal to the AAT’.

Privacy

The Committee noted its scrutiny concerns regarding the

expansion of the basis on which persons may be required to disclose certain

information and the impact this may have on the right to privacy. The Committee

considered that the explanatory materials did not adequately address these

concerns, and drew this matter to the attention of the Senate.

In Scrutiny Digest 8 of 2019, the Scrutiny of Bills

Committee considered the Bill and reiterated its concern about privacy. The

Committee asked the Minister to provide further detail about:

- why lowering the current ‘reasonable belief’ standard is

necessary given that a ‘reasonable belief’ may be formed on the basis of

intelligence gathered while investigating a potential anti-doping rule

violation and

- any safeguards that will be in place to guard against the

unauthorised use or disclosure of personal information obtained under a

disclosure notice. [64]

These points are discussed below under the heading ‘Part

4—Lowering the burden of proof for issue of a disclosure notice’.

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

On 1 August 2018, Senator Don Farrell, Shadow Minister for

Sport, issued a media release stating that the Australian Labor Party (Labor)

welcomed the release of the Wood Review and urged the Government to

consult with national sporting organisations and other key stakeholders.[65]

In addition the Labor Party National Platform states:

Labor will ensure Australia is at the forefront of efforts

against doping and match fixing in sport and, in partnership with sports, will

provide leadership in the international effort to protect the integrity of

sport.[66]

The policy of The Australian Greens on Sport and Physical

Recreation includes support for:

- a drug free sporting environment

- governance structures and financial structures in sporting

organisations and associations to ensure integrity in all sporting codes

- reduced influence of gambling on sport through:

- more

tightly regulated sports betting

- education

about the risks and harms of gambling on sport and

- restricted

advertising of gambling on sports.[67]

As at the date of writing this Bills Digest, it appears

that no non-government parties or independents have indicated a position on the

Bill.

Position

of major interest groups

While there have been no statements from major interest

groups on the Bill as drafted, there was extensive consultation during the Wood

Review and some groups have issued statements about the Government

Response.

ASADA

ASADA fully endorses the Government Response,

including the formation of SIA.[68]

Australian Olympic

Committee

The Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) supports all the

recommendations of the Wood Review, ‘[a]s for Anti-Doping

Rule Violation matters, the AOC fully supports the establishment of a National

Sports Tribunal and generally on the basis proposed’.[69] It also commends the Government Response, while saying

it would continue to study it and questioning whether the Government had

committed sufficient funding.[70]

Paralympics Australia

Paralympics Australia welcomes the Government Response. CEO

Lynne Anderson said:

Paralympics Australia also supports the concept of a new

National Sports Tribunal, which is proposed to hear anti-doping rule violations

and other sports disputes, and resolve them in a consistent, cost-effective and

transparent manner.[71]

Coalition of Major Professional

and Participation Sports

The Coalition of Major Professional and Participation

Sports (COMPPS) represents the major participation sports in Australia

including Australian football, rugby, football, cricket, rugby league, netball

and tennis. COMPPS submission to the Wood Review on funding levels for

ASADA to combat anti-doping states, ‘[c]urrently, ASADA is insufficiently

funded and resourced to provide the type, and level, of support being sought by

the Sports. Previously, ASADA had a strong detection and investigation arm’. [72]

It notes that each sport it represents has ‘now established its own integrity

unit with responsibility for managing [anti-doping rule violation] ADRV

processes’:[73]

Despite this ongoing allocation of resources, we submit that current

arrangements are not capable of adequately addressing the doping threat.

Specifically, we contend that the Sports are not being given the support that

they require by ASADA to effectively combat the current doping threat ...

Accordingly, ASADA has been unable to satisfactorily perform a number of its

vital functions that support the Sports’ ADRV processes.[74]

Exercise and Sports

Science Australia

Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) is an

accrediting body for professional support personnel and sports scientists. It

supports the findings in chapter 4 of the Wood Review.[75]

Australian Athletes

Alliance

The Australian Athletes Alliance (AAA) is the peak body for Australia’s elite professional

athletes, through eight major player and athlete associations that cover

professionals in cricket, AFL, netball, basketball, football, rugby league,

rugby union and horse-racing (jockeys).[76]

AAA asked the Wood Review to endorse sport-specific, differentiated,

anti-doping and sanction regimes – an approach which would result in those

regimes not being Code-compliant.[77]

The Wood Review saw

no merit in that approach:

In our view, there is no overall

benefit from changing the present policy and thereby creating a dual system in

Australia for national-level athletes. No evidence has been submitted to the

Review which would warrant such an amendment to current anti-doping

arrangements.

The independence and objectivity

inherent in applying the Code to all Australian sports makes for a

simpler, clearer and consistent anti-doping system, beyond the reach of

internal sport politics and collective bargaining.

Accordingly, we do not agree with

AAA’s argument regarding the reach of the Code in relation to sanctions

or the ‘fit’ of the world anti-doping system overseen by WADA. Our view is that

penalties under the Code are sufficiently flexible to allow for

effective application in a professional team-sports environment. [78]

The approach of the Wood Review is consistent with

the aims of WADA:

An aim of the 2015 Code is to unify doping regulations

throughout the world, such that the Code might be considered similar to

a body of international law ... In respect to the [Code’s] reach into

sports of national, rather than international operation the Code

describes a purpose, ‘To ensure harmonized, coordinated and effective

anti-doping programs at the international and national level with regard to

detection, deterrence and prevention of doping.’[79]

Commonwealth Games Australia

Commonwealth Games Australia (CGA) supports the

consolidation of existing Federal Government functions in sports integrity

under a new agency – Sport Integrity Australia – and the conduct of a two-year

pilot of a new National Sports Tribunal. CGA also supports the signing of the Council

of Europe Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions (Macolin Convention). CGA President Ben Houston said the

National Sports Tribunal will benefit Commonwealth Games member sports, many of

whom struggle with the resourcing in this area.[80]

Financial implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the Bill will

have no financial impact on the Commonwealth.[81]

The AOC and COMPPS both argued that a further commitment of Commonwealth

funding is necessary to ensure the NAD scheme is effective.[82]

Some smaller sports NSOs see financial benefit in having access to a nationally

resourced sports tribunal.[83]

Statement of Compatibility

with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[84]

Human rights engaged

The Government acknowledges at page 2 of the Explanatory

Memorandum that the Bill engages the following rights:

- Article 2(3) of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

– right to an effective remedy

- Article 14(2) of the ICCPR –

right to presumption of innocence (which includes the right not to be compelled

to self-incriminate[85])

- Article 17 of the ICCPR –

privacy and reputation.

The Explanatory Memorandum discusses the human rights

issues in detail in the Statement of Compatibility

with Human Rights at pages 2–10. The Bill removes two opportunities for

an athlete or support person to contest the evidence and process involved in

the imposition of an infraction notice for an ADRV. However, the recipient is

still given:

- an opportunity to be heard before the infraction notice is issued

and

- the opportunity to contest the notice in an independent tribunal.

The Government considers that the rights to a fair hearing

and a presumption of innocence are, therefore, largely preserved.

However, since the Bill will lower the standard of proof

for the issuing of a disclosure notice and abolish the privilege against

self-incrimination when answering questions, it would appear that the Bill

engages the right not to be compelled to self-incriminate under the ICCPR and also the common law privilege against

self-incrimination.[86]

The proposed disclosure notice provisions and their

justification are discussed further under the ‘Key

issues and provisions’ heading below.

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing this Bills Digest, the Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights had not yet reported on this Bill.

Key issues and provisions

Constitutional basis for legislation

While there is no express Commonwealth legislative power

for regulating sport or athlete drug use, section 3 of the ASADA Act identifies implementing Australia’s

international anti-doping obligations as the foundation for the Act. Australia

is a party to several international conventions which provide a basis in the

external affairs power for Parliament to legislate. The ASADA Act and ASADA Regs implement the Council of

Europe Anti-Doping Convention 1989,[87]

the UNESCO International Convention against Doping

in Sport,[88] and the Code. The Commonwealth is

therefore able to rely on the external affairs power as the primary source of

its power to legislate in this area.[89]

The voluntary submission to the Code and NAD scheme

by organisations, athletes and other personnel through contracts extends the

effective reach of the NAD scheme. Voluntary contractual submission to an anti-doping

code means that a constitutional challenge will probably never be effective on

its own to overturn an ADRV infraction.

Abolishing the ADRVP and appeal to the AAT

The ADRVP was created by amendments inserted in the ASADA Act in 2009.[90]

ASADA was set up in 2006 and assumed the functions of a variety of existing

agencies. It took over roles in drug testing, education and advocacy from the

Australian Sports Drug Agency; it took over the Australian Sports Commission’s

(ASC) policy development, approval and monitoring roles; it incorporated the

ASDMAC and was given the power to investigate all allegations of ADRV in the Code.

The CEO of the Australian Sports Drug Agency was appointed ASADA CEO and a

Board headed by the ASADA Chair was appointed.[91]

The AOC extensively criticised the intertwined nature of

the ASADA governance arrangements at the time it was set up. AOC President John

Coates said ASADA would become investigator, prosecutor, judge and jury.[92]

The AOC considered there was insufficient provision for

the separation of ASADA‘s policy making, administrative, investigative and

prosecution functions. It particularly noted that there needed to be proper

protection of the rights and roles of Australian sports organisations, athletes

and athlete support personnel. The investigative regime to be put in place did

not require ASADA to put its case to an independent hearing before declaring an

athlete guilty, the AOC noted. And once an investigation was complete, ASADA

alone had the power to determine whether an athlete should be sanctioned.[93]

In response to a number of controversial doping

investigations, the governance arrangements were changed in 2009 to create a

marked distinction between the administrative and investigative functions and

the adjudication functions of ASADA.[94]

The ASADA Chair position was abolished and financial and administrative functions

concentrated in a new ASADA CEO position. Instead of the Board, a specialist

Advisory Group was formed solely to give advice to the CEO in relation to the

CEO’s functions. The group had no adjudicatory or administrative functions. The

ADRVP was established to take on the quasi-judicial role of deliberating on

rule violations. Day to day anti-doping policy issues were confined to the

administrative sector.[95]

In some respects, the Wood Review proposes undoing

those 2009 changes. However, the AOC does not oppose the proposed amendments.[96]

The duplicated process was designed to provide an independent check on the

power of the ASADA CEO to issue infraction notices. Stakeholders agreed,

however, that this had not been the practical outcome of the system. Instead it

had resulted in a cumbersome, time wasting process that was of little

assistance to the sports tribunal.[97]

Wood Review

consideration of ADRV process

The Wood Review examined the current ADRV process

and found it was overly bureaucratic, inefficient and cumbersome.[98]

COMPPS told the Wood Review:

The ADRV process is generally convoluted and confusing, and

difficult for athletes and other stakeholders to understand. It is too

bureaucratic, involving an inordinate number of procedural steps.[99]

Before an infraction notice is issued, the current ADRV

process requires:

- consideration of evidence by the ASADA CEO and

- a second consideration by the ADRVP.

ASADA estimates that the minimum time to pass from the

ASADA CEO ‘show cause notice’ through to the end of the ADRVP process is eight

weeks.[100]

ASADA noted that the ADRVP has never once overruled the ASADA CEO. The ADRVP

Chair explained:

The threshold that the Panel applies is that there is a possibility that an ADRV has occurred. In practice

this has meant that the Panel hasn’t ever disagreed with the CEO, as the threshold that the CEO applies is higher in the

first instance.[101] [emphasis added]

The decision by the ADRVP to assert an ADRV (marked ‘5’ in

Flowchart 1

above) can then be challenged in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal

(AAT). The WADA Code provides that anti-doping decisions can be appealed

to CAS.[102]

Appeals can be made to the CAS Appeals Arbitration Division and the Swiss

Federal Tribunal.[103]

COMPPS recommended that the ADRVP be

abolished.[104]

ASADA suggested that the opportunity for an athlete to respond to an ADRV

allegation be deferred until the infraction notice is received.[105]

However, the Wood Review considered that issuing

the ‘show cause notice’ had the merit of allowing the athlete the opportunity

to engage with the allegations prior to hearing and potentially avoid delays at

the hearing or avoid a hearing altogether if the athlete acknowledges the infraction.[106]

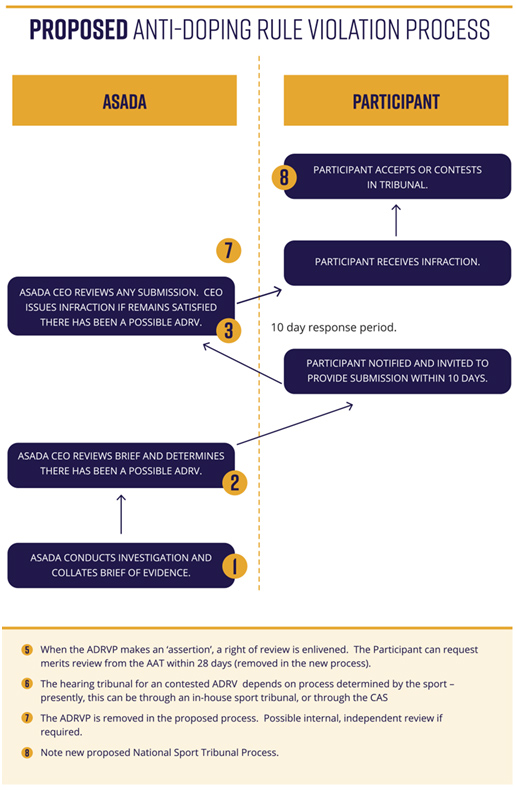

It therefore proposed removing the ADRVP but allowing the athlete an

opportunity to be heard before the ASADA CEO issues an infraction notice.[107]

The Wood Review also recommended abolition of

appeals to the AAT.[108]

For the purposes of procedural fairness, there is no need for

any aspect of the pre-hearing phase of the ADRV process to be subject to AAT

review.

In our view, so long as participants have the opportunity to

respond to allegations before the issue of an infraction notice – and have access

to an affordable, efficient, and effective tribunal to have their matter heard

should they elect – recourse to the AAT for a merits review of any aspect of

the pre-hearing ADRV process is unnecessary and potentially dilatory.[109]

Under the Wood Review proposals, the athlete would

then contest the notice in the NST. Appeal to CAS Appeals Arbitration Division

would also still be available.[110]

It appears that the athlete’s right to a fair hearing and

an effective remedy are preserved under the proposed process. The amendments

proposed in Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Bill appear to maintain

compliance with Australia’s international obligations under the ICCPR, Council of Europe Anti-Doping Convention 1989 and the UNESCO International Convention against Doping in Sport.

All major interest groups supported the recommendation.

The Government agreed with the recommendation and the recommended process (see Flowchart 2

below) is reflected in the Bill.

Item 16 of Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Bill repeals

existing subsection 14(4) of the ASADA Act

which requires the NAD scheme to establish a right of appeal to the AAT. A

consequential amendment to the NAD scheme will be necessary to abolish the

right to appeal to the AAT for review of a decision of the ADRVP.[111]

Flowchart

2: proposed ADRV process[112]

Source: Wood et al., Wood Review, op. cit., p. 137

Lowering the threshold for

issue of a disclosure notice

The ASADA CEO may issue a

disclosure notice requiring a person to, within a specified period:

- attend an interview to answer

questions

- give information of the kind

specified in the notice and/or

- produce documents or things of

the kind specified in the notice.[113]

At present, three ADRVP members must

agree that the ASADA CEO reasonably believes that a person has ‘information,

documents or things that may be relevant to the administration of the NAD

scheme’ before the CEO can issue a disclosure notice.[114]

The Wood Review found that the present threshold of

reasonably believes resulted in disclosure

notices generally only being granted by the ADRVP in circumstances where ASADA

already had evidence to suggest that an ADRV has taken place—for instance, a

returned positive sample or adverse analytical finding (AAF). [115]

The Review therefore recommended that the threshold be changed to reasonably suspects.

The proposed amendments to paragraphs 13(1)(ea) and

paragraphs 13A(1A)(a) and (b) change the threshold

for the issue of a disclosure notice from reasonably

believes to reasonably suspects.[116] This change in threshold, as well as the repeal in item 13 of Schedule 1

to the Bill of the need for three ADRVP members to agree with the notice,[117] will result in a significantly reduced threshold for the

issue of a coercive disclosure notice.

Neither the Wood Review nor the Explanatory

Memorandum gives a clear reason why the ASADA CEO only issues a disclosure

notice under the present legislation where evidence of an ADRV is already

available. That is not the effect of the ASADA Act

on its face. Paragraph 13(1)(f) of the ASADA Act makes it clear that

investigation of possible violations of the anti-doping rules is a

responsibility of the ASADA CEO.

The ASADA Act and the

NAD scheme do not require, except in the case of medical practitioners, that

the CEO hold a reasonable belief that any person has been involved in the

commission or attempted commission of an ADRV.[118]

The threshold of reasonable belief instead applies to whether ‘the person has

information, documents or things that may be relevant to the administration of

the NAD scheme’. As Middleton J observed in the Essendon

FC case, the responsibilities of the ASADA CEO in administering the NAD

scheme are very wide and include all the matters in clause 1.02 of the scheme.[119]

Note that the proposed amendment to paragraph 13(1)(ea)

of the ASADA Act (at item 43 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) will not change

this position, as the threshold of reasonable suspicion does not apply to

whether an ADRV has occurred, but to whether ‘the person has information,

documents or things that may be relevant to the administration of the NAD

scheme’.

However, in proposed amendments to paragraphs

13A(1A)(a) and (b) (at item 44 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) the threshold is then linked to an additional requirement,

for medical practitioners only, that the ASADA CEO reasonably suspects that the

person has been involved, in their capacity as a medical practitioner, in the

commission, or attempted commission, of a possible ADRV.

Departure from

Attorney-General’s Department Guide to Framing Offences

The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) Guide to Framing

Offences (the Guide) says that a

document disclosure provision should normally:

- impose a threshold of ‘reasonable grounds to believe’ that a

person has custody or control of documents, information or knowledge which

would assist the administration of the legislative scheme

- give a person 14 days to comply with the notice and

- impose a maximum penalty for non-compliance of six months

imprisonment or a 30 penalty unit fine.[120]

In contrast to the above, the amendments in Part 4 propose:

- a threshold of ‘reasonable suspicion’ the person has information,

documents or things that may be relevant to the administration of the NAD

scheme

- no limit to the period that the ASADA CEO may specify in the

notice and

- a penalty for non-compliance of 60 penalty units but no penalty

of imprisonment is applied.[121]

The Wood Review said the

reasonable suspicion ‘threshold for the exercise of similar powers is relatively

commonplace in comparable statutory schemes and would be appropriate in these

circumstances’ – but did not provide any examples.[123]

The Explanatory Memorandum

argues that some jurisdictions allow search warrants to be issued at a threshold

of “suspicion” and that the nature of a disclosure notice is quite different

and less intrusive than a search warrant because it does not permit entry into

premises.[124]

The Regulatory Powers

(Standard Provisions) Act 2014 provides that a search warrant may be

issued if there are ‘reasonable grounds for suspecting’ that evidential

material may be on the premises within a specified time.[125]

Although the threshold in that provision is lower, the material sought is much

more tightly defined, requiring particular material, an association with an

offence and a time limit. The privilege against self-incrimination is also not

abrogated by the use of those powers.[126]

The analogy with search warrants

is not complete since disclosure notices can also compel a person to attend for

questioning. A person can generally only be compelled to attend for questioning

if a court issues a warrant for their arrest or a person, usually a police

officer, arrests them without a warrant. The general requirement for issue of a

warrant, or for arrest without a warrant, is that the person issuing the

warrant or making the arrest believes on reasonable grounds that the person has

committed or is committing an offence.[127]

Even then, although a person arrested for a criminal offence may be questioned,

they have a right to remain silent.[128]

In light of the broad responsibilities of the ASADA CEO

and the width of the phrase ‘relevant to the administration of the NAD scheme’,

there is some doubt whether a change to the threshold for issue of a disclosure

notice is necessary. It may be sufficient for the ASADA CEO to fully utilise

the current legislation.

Comparative coercive questioning powers in

Commonwealth legislation

There are a number of Commonwealth officers and

authorities who are given power to conduct coercive questioning of natural

persons under threat of penalty. Some examples are summarised below.

Tax Commissioner

A person may be required by law to attend before the

Commissioner to give information, or produce documents.[129]

The Commissioner may question any person for the purpose of the administration

or operation of a taxation law. There is no preliminary threshold.[130]

Refusal or failure to comply is subject to a maximum fine of 20 penalty units for

a first offence and 50 penalty units and 12 months imprisonment for a third or

subsequent offence.[131]

A person issued a notice to attend and give evidence cannot refuse to answer on

the grounds of self-incrimination.[132]

Royal Commissions

A Royal Commission may summon a person to give evidence

and produce a document or thing.[133]

There is no apparent threshold to exercise that power, however it is a defence

to a prosecution for failing to comply to show that the document or thing

required was not relevant to the commission’s inquiry.[134]

It is an offence, subject to a maximum penalty of two years imprisonment, to

fail to appear, or fail or refuse to answer a question or produce a document or

thing.[135]

A person is not excused from giving evidence on the grounds

of self‑incrimination; however, evidence given to a Royal Commission is

not admissible in evidence against the person in civil or criminal proceedings

in any Australian court.[136]

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC)

and certain officers may issue a notice requiring a person to attend and give

evidence, provide information or produce documents.[137]

The ACCC or officer must have reason to believe that a person is capable of

furnishing evidence on a matter the ACCC may investigate.[138]

The High Court in Daniels Corporation v ACCC took the view that the “reason

to believe” threshold was a relatively low one.[139]

Non-compliance is an offence subject to a penalty of 100

penalty units or two years imprisonment.[140]

A person is not excused from complying if the evidence, information or

documents would tend to incriminate the person; however, the evidence cannot be

used against the person in criminal proceedings other than obstruction and

providing false evidence offences.[141]

Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner

The Commissioner may summon a person to give evidence,

produce documents or other things, if the Integrity Commissioner has reasonable

grounds to suspect that the evidence, documents or things will be relevant to

the investigation of a corruption issue or conduct of a public inquiry.[142]

It is an offence with a maximum penalty of two years imprisonment to fail or

refuse to answer questions, produce a document or thing or obstruct an officer.[143]

The privilege against self-incrimination is abrogated;

however, a ‘use immunity’ is substituted so that the evidence, information or

document produced is not admissible in evidence against the person in a

criminal proceeding, a proceeding for the imposition or recovery of a penalty

or a confiscation proceeding.[144]

Removing self-incrimination as a defence to answering

questions

Both the common law and the ICCPR

recognise a right to not be forced to incriminate oneself – often referred to

(in a common law context) as the privilege against self-incrimination. The

common law privilege against self-incrimination is not confined to criminal

proceedings. Middleton J summarised the common law in the Essendon FC case:

The common law privilege against self-incrimination entitles

a person to refuse to answer any question, or to produce any document, if the

answer or the document would tend to incriminate that person: see Pyneboard

Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission [1983] HCA 9; (1983)

152 CLR 328 (‘Pyneboard’). Although broadly referred to as the

privilege against self-incrimination, the concept encompasses distinct

privileges relating to criminal matters, and self-exposure to a civil or

administrative penalty and self-exposure to the forfeiture of an existing

right.

In Rich v Australian Securities and Investments

Commission (2004) 220 CLR 129; [2004] HCA 42 at [26]–[29] the

High Court (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ) discussed the

nature of penalties and forfeitures which attract the privileges: “... The

penalties and forfeitures which attract the privileges include, but are not

confined to, monetary exactions ...”

The privilege has been described by the High Court as a human

right which protects personal freedom, privacy and dignity: see Environment

Protection Authority v Caltex Refining Co Pty Ltd [1993] HCA 74; (1993) 178 CLR 477 at

498.

Rationales for the privilege include preventing the abuse of

power and convictions based on false confessions, protecting the quality of

evidence and the requirement that the prosecution prove the offence, and

avoiding putting a person in a position where the person will be exposed to

punishment whether they tell the truth, lie, or refuse to provide the

information.

Some protections, such as the competency of an accused person

to give evidence as a witness for the prosecution, cannot be waived: see,

eg, Kirk v Industrial Court of New South Wales (2010) 239 CLR

531; [2010] HCA 1 at 565 [51]-–[52] and Lee

v The Queen (2014) 308 ALR 252; [2014] HCA 20 (‘Lee v The Queen’)

at [33].

There seems little doubt that the privilege against

self-incrimination, although a “human right”, can be waived. The privilege

applies in non-judicial proceedings, such as inquiries, unless it is expressly

or impliedly abrogated by a governing statute: Pyneboard, 340-341, 344.

One of the problems with the recognition of the privilege

against self-incrimination outside a court exercising judicial power is that

there is the practical problem of how the decision maker is to properly

consider the claim for privilege, and the consequences that may follow from a

refusal to answer... However, any abrogation of the privilege against

self-incrimination must be clear and unmistakable.[145]

Current provisions protecting individuals under

compulsory questioning

The ASADA Act currently treats the privilege

differently according to whether the incrimination or exposure to penalty might

arise from documents or things produced, or from answers given at a compulsory

interview.

Subsection 13D(1) of the ASADA

Act provides that an individual does not have to answer a question or

give information if that might incriminate the person or expose them to a

penalty. However the same protection is not extended to documents or things.

Existing subsection 13D(2) provides the limited

protection that, if a person does produce a document or information, it cannot

be used against them in criminal proceedings, or proceedings that might result

in a penalty, other than proceedings for an offence against the ASADA Act or ASADA Regs, or an offence of

providing false or misleading information under the Criminal Code Act

1995.

Proposed abrogation of privilege

Proposed subsections 13D(1) and (2)

(at item 47 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) abolish

the privilege against answering questions or producing information which might

incriminate the person or expose them to a penalty.

The Bill substitutes a ‘use immunity’ which provides that

the evidential material cannot be used against the person in criminal

proceedings. As currently, information provided can be used in proceedings

under the ASADA Act or the ASADA Regs (and

therefore the NAD scheme), and for prosecution for providing false or

misleading information (sections 137.1 and 137.2 of the Criminal Code). The information cannot be used in

a criminal prosecution for any other offence.

Therefore, unlike the current situation, the amendment

would allow a person to be compelled to answer questions or give information

that could then be used in evidence against them in ADRV proceedings. The

Explanatory Memorandum notes:

This amendment ... further aligns ASADA’s powers with

pre-existing contractual powers utilised by many national sporting

organisations. [147]

The point is somewhat disingenuous in a context where

ASADA has been encouraging and approving those very ‘pre-existing contractual

powers’, apparently since at least January 2015, to empower its own investigations.[148]

That context is discussed above under heading ‘Background’ and

immediately below.

Coercive questioning powers were proposed in 2013

As mentioned above, prior to 1 August 2013, neither ASADA

nor the CEO had any power to compel a person to attend an interview or provide

information. In February 2013, the Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment Bill 2013 was introduced to

Parliament. The Bill, as introduced, proposed a complete abrogation of the

privilege against self-incrimination in ASADA investigations.

The Bills

Digest for the 2013 Bill contains comments from interest groups on the

proposal:

The Law Institute of Victoria, in opposing the section in its

submission to the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References

Committee, declared that the right not to self-incriminate is a basic human

right. As such, it should not be abrogated. In the Society’s view: ‘if ASADA

has proof that a breach of the Code has occurred, the burden of proving

such should rest with ASADA, not with a person to provide evidence establishing

their guilt’.

The Australian Athletes’ Association cited the Administrative

Review Council and Attorney-General’s Department reports in making the argument

that there is no evidence to justify removing the right not to self-incriminate

when investigating doping offences. Doping offences are no more major than

serious criminal matters, which are regularly investigated without undermining

the right. The Athlete’s Association is not convinced by the Bill’s Statement

of Compatibility with Human Rights, which claims that the abrogation of the

right against self-incrimination is necessary ‘to ensure that possible doping offences

under the NAD scheme are able to be properly investigated’.[149]

In 2013, Brendan Schwab, the General Secretary of the

Australian Athletes’ Alliance said of the proposed abrogation of the privilege:

... the whole concept that athletes would face a criminal

penalty for breach of contract is ridiculous and absurd ... the threat of jail

terms for those who refuse to be interviewed by Australia’s anti-doping agency

infringes the basic civil rights of sportspeople ... everyone should be under no

illusion that the powers ... under the existing anti-doping codes which have been

agreed to by athletes are extreme.[150]

Parliament did not agree to the extensive powers

requested; amendments introduced in the Senate to preserve a privilege against

self-incrimination for natural persons were passed. However, according to

Barrister Anthony Crocker, sports organisations have since found a way around

Parliament:

Nonetheless, since 1 January 2015, ASADA has been able to

overcome this restriction. It has prepared a template anti-doping policy

(‘ADP’) for sporting administration bodies to use. This policy reflects a full

abrogation of the privileges.

This is a most unsatisfactory development. ASADA is the

national body charged with the task of investigating anti-doping matters so as

to maintain the integrity of sport. It sought a range of additional powers from

the Commonwealth Parliament. Not all of those powers were granted. What ASADA

could not obtain through the ‘front door’, it has given to itself through the

‘back door’, by drafting a template that is not consistent with the ASADA

Act.

The High Court is very firm as to the rules concerning the

privilege against self-incrimination. When amending the ASADA Act in

August 2013, the Parliament was equally clear. Unless and until ASADA corrects

the current situation, it will continue to play outside those rules.[151]

In late 2015 ASADA was criticised by a journalist for

‘compelling athletes to give up their common law right to silence’.[152]

ASADA responded in a media

release on 29 November 2015:

ASADA does not mandate any sport to abrogate athletes of

their privilege against self-incrimination in anti-doping investigations. Under

ASADA's legislation, sports determine their own anti-doping policies, which are

contractual arrangements with their members.[153]

It noted that the AOC had amended its anti-doping by-law

to include a provision abrogating the privilege of self-incrimination and

continued:

ASADA CEO Ben McDevitt said: ‘The AOC is a fantastic partner

and ASADA supports them for going above and beyond in its fight against doping.

Many other sports have also chosen to include the provision in their own

anti-doping policies and they too have ASADA’s full support in their commitment

to protecting their clean athletes.’[154]

The media release did not address the ASADA anti-doping

policy template.

The AOC has long opposed the

privilege against self-incrimination in the anti-doping context and its

President, John Coates, welcomed Wood Review recommendations that

athletes and support people be compelled to give evidence about doping:

I am particularly pleased that the [Wood Review recommends]

legislation establishing the Tribunal will include ‘the power to order a

witness to appear before it to give evidence, and/or to produce documents or

things; and the power to inform itself independent of submission by the

parties’.

The AOC has long argued for this legislative support to the

fight against doping in sport and, having repeatedly been knocked back,

introduced similar requirements in its Anti-Doping Policy - making it a

condition for member National Federations nominating athletes for selection in

Australian Olympic Teams that they must include these requirements in their

Anti-Doping policies...

So very much better that this be by statute rather than

relying on contractual arrangements.[155]

Public policy and coercive questioning

In the coercive questioning schemes compared above, except

the taxation regime which is motivated by the national interest in protecting

public revenue, the witness is protected from the immediate consequences of

giving evidence under compulsion. The witness is not being examined for the

primary purpose of obtaining evidence against them; instead, their evidence is

intended to serve a higher public policy goal. A ‘use immunity’ is given to

encourage truthfulness.

The ‘use immunity’ provided here, however, it is not

sufficiently wide to protect from the absolute liability ADRV findings which

could result from the compelled evidence. Those absolute liability ADRV are

then followed by sanctions including mandatory suspensions and automatic loss

of results and prizes. The losses may be substantial and affect other team

members. All this occurs in a context where the investigator is also the

prosecutor and facilitator of the sanction, and all without access to a court.

In the context of the Bill and an ADRV, it is questionable

whether removal of the privilege against self-incrimination could be considered

proportionate to the public policy goals, particularly when it was strenuously

opposed in 2013 by interest groups which represent athletes. It is difficult to

reconcile the strong opposition of these groups with the framework of

supposedly voluntary contractual submission to coercive questioning.

Human rights obligations

The Government acknowledges in the Explanatory Memorandum

that the Bill engages Article 14(2) of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)—the

right to presumption of innocence[156]

(which includes the right not to be compelled to self-incriminate[157]).

Human rights in the context of the international

anti-doping regime and the Code requirement for a ‘fair hearing’ are

discussed extensively by Professor Andrew Byrnes in Chapter 5 of Doping in

Sports and the Law.[158]

Byrnes identifies that, in terms of international human rights law, there is a

developing body of opinion that the obligation of the state is expanding beyond

the state merely avoiding encroaching on a person’s human rights to protecting

persons against encroachment on their rights by non-state actors.[159]

Byrnes offers the opinion:

The hybrid nature of the anti-doping regime and its potential

application in national systems where the investigation and disciplinary

proceedings are conducted as the exercise of or with the support of state power

are likely to engage the human rights obligations of the state under

national and international law.[160]

Since the abrogation of the privilege against