Introductory Info

Date introduced: 24 July 2019

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: Schedules 1 to 4 commence on the first 1 January, 1 April, 1 July or 1 October after Royal Assent. Schedules 5 to 7 commence the day after the Act receives Royal Assent.

The Bills Digest at a glance

The Treasury

Laws Amendment (2019 Tax Integrity and Other Measures No. 1) Bill 2019 (the

Bill) contains seven unrelated Schedules.

Summary of the Bill

- Schedule 1 prevents tax exempt entities with concessional

loans that become privatised from obtaining an unintended tax deduction under

the Taxation of Financial Arrangement (TOFA) rules.

- Schedule 2 prevents partners in a partnership from

accessing the CGT small business concessions where there has been an assignment

of a non-membership interest.

- Schedule 3 prevents deductions being claimed in respect of

vacant land where that land is not being held for the purpose of carrying on a

business. However, these changes do not apply to certain entities.[1]

- Schedule 4 extends an existing anti-avoidance rule for

trustee beneficiaries to family trusts.

- Schedule 5 seeks to create a legislative framework that

decriminalises the disclosure of taxpayer information by a taxation officer where

an authorised disclosure is made to a credit reporting bureau.

- Schedule 6 confers on the ATO the function of developing

and administering an electronic invoicing system for users in both Australia

and foreign countries for the purposes of adopting the Pan-European Public

Procurement Online interoperability framework.

- Schedule 7 prevents salary sacrificed superannuation

contributions being used to supplement an employer’s super guarantee

contribution.

Key Issues

The majority of issues raised by stakeholders to date

relate to Schedules 3 and 5 of the Bill.

Schedule 3 — vacant land

A number of stakeholders have expressed concern that the operation

of the proposed amendments may unfairly target or disadvantage farmers that do

not use a corporate structure and do not have a permanent or substantial structure

on their land.

Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand (CAANZ)

and the ALP have also raised concerns that the definition of vacant land

amendment may potentially capture the Opal and Mascot apartments.[2]

CPA Australia has raised uncertainty about whether trying to avoid the

operation of the proposed amendments by incorporating an entity, will trigger

the application of the General Anti-Avoidance Rule contained in Part IVA of the

Income Tax Assessment Act 1936.[3]

Further, based on an examination of the relevant

legislation it appears that the Bill may not achieve its stated goals of

reducing complexity or reducing compliance and administrative costs for the

ATO. This is because:

- the legislation introduces a number of new concepts that are not

defined in the proposed amendments and

- although the Bill modifies the tax law to deny deductions for

certain taxpayers where they are not carrying on a business, the ‘carrying on a

business’ test is not a bright line test and requires an analysis of several

factors. In particular, it is not clear how the proposed amendments provide

non-exempted entities with additional certainty, as the availability of a

deduction for non-exempted entities will be decided on a case by case basis.

Schedule 5

Schedule 5 creates a broad legislative framework under

which taxpayer debts may be disclosed by a taxation officer to a credit

reporting bureau. In particular, the proposed amendment enables the Minister to

determine, by way of legislative instrument:

- the class of taxpayers who may be subject to tax debt disclosure

and

- to some extent, the procedural requirements that must be met in

order for the tax debt to be disclosed.

This raises the question as to whether Parliament should

be providing an exception to criminal offences, without knowing the full

details of who will be affected and how the regime will be administered.

Purpose and

structure of the Bill

The Treasury

Laws Amendment (2019 Tax Integrity and Other Measures No. 1) Bill 2019 (the

Bill) consists of seven unrelated Schedules:

- Schedule 1 amends the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1936 (ITAA 1936) to prevent inappropriate tax

deductions arising under the Taxation

of Financial Arrangement (TOFA) rules in relation to concessional loans held

by entities that are subsequently privatised

- Schedule 2 amends the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997) to improve the integrity of the Capital

Gains Tax (CGT) small business concessions, by preventing partners in a

partnership from accessing the concessions where there has been an assignment

of a non-partnership membership interest (that is, the assignee is made

entitled to a share of partnership income, but is granted no other rights or

interests over the partnership)

- Schedule 3 amends the ITAA 1997 to prevent

deductions being claimed by certain taxpayers that relate to vacant land that

is not being held in connection with the carrying on a business

- Schedule 4 amends the ITAA 1936 and the Taxation

Administration Act 1953 (TAA) to extend an existing

anti-avoidance rule to family trusts engaged in circular

trust distributions

- Schedule 5 amends the TAA to enable taxation

officers to disclose the business tax debt information of a class of taxpayer

(determined by way of legislative instrument) to credit reporting bureaus where

certain requirements are satisfied

- Schedule 6 amends the TAA to confer on the ATO

functions and powers to develop and administer an electronic invoicing system

(E-invoicing) for users in both Australia and foreign countries

- Schedule 7 amends the Superannuation

Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (SGAA) to prevent salary

sacrificed superannuation contributions counting towards an employer’s superannuation

guarantee contribution (SGC).

Structure of

this Bills Digest

As the matters covered by each of the Schedules are

independent of one another, the relevant background, stakeholder comments,

committee consideration and analysis of the provisions are set out under each

Schedule number.

History of

Schedule 7 of the Bill

The Treasury

Laws Amendment (Improving Accountability and Member Outcomes in Superannuation

Measures No. 2) Bill 2017 (2017 Bill) was introduced into the House of

Representatives on 14 September 2017 and was passed by the House on 23 October

2017.[4]

The 2017 Bill was introduced into the Senate on 13 November 2017 and lapsed on

1 July 2019 at the end of the 45th Parliament.

The present Bill was introduced into the House on 24 July

2019 and was passed unopposed by the House on 1 August 2019.[5]

Schedule 7 of the Bill is in the same terms as Schedule 2 of the 2017 Bill, the

only material difference is the proposed start date.

A Bills Digest was prepared in respect of the 2017 Bill.[6]

Much of the material in this Bills Digest under the heading ‘Schedule 7: superannuation

guarantee contribution integrity measure’ has been sourced from that earlier Bills

Digest.

Commencement

- Sections

1 to 3 commence on Royal Assent

- Schedules 1 to 4 commence the first 1 January, 1 April, 1 July or

1 October to occur after the day of Royal Assent

- Schedules

5 to 7 commence the day after Royal Assent.[7]

Committee

consideration

Senate

Economics Legislation Committee

The provisions of the Bill were referred to the Senate

Economics Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 5 September 2019.[8]

Details of the inquiry are at the inquiry

homepage. Submissions closed on 15 August 2019. The Committee received 23

submissions as well as additional information and answers to questions on

notice. The Committee also held a public hearing on 19 August 2019. The

Committee delivered its report into the inquiry to the Senate on 4 September 2019.[9]

The Committee recommended that the Bill be passed in its

entirety by the Parliament, but encouraged the ATO to issue further public

guidance on the operation of Schedule 3[10]and

expressed some concerns about the privacy aspects of disclosing tax debts

(Schedule 5).[11]

The Committee also stated that it would like to see Treasury and the ATO

address any unintended consequences of Schedule 3 for property owners where the

property is unusable for reasons outside their control.[12]

Australian Labor Party (ALP) and Centre Alliance Senators provided

the following additional comments:

- the ALP called on the Government to bring forward the SGC

amendments to operate from 1 July 2019. The ALP also stated that Schedule

5 should be amended so as to increase the notice period to 28 days, and tax

practitioner representatives to be notified if a client is to have their tax

debt information disclosed

- Centre Alliance supported the broad intent of the Bill, but

called on Schedule 5 to be amended so as to incorporate the recommendations of

the Inspector General of Taxation and Taxation Ombudsman.

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

(Scrutiny of Bills Committee) is concerned with the retrospective application

of Schedules 1 and 2 of the Bill.[13]

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee’s concerns are discussed further under ‘Schedule

1: concessional loans involving tax exempt entities’ and ‘Schedule 2: enhancing

the integrity of the small business CGT concessions’.

Statement of

Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[14]

The Government considers that Schedules 1, 2,

3, 4, 6 and 7 of the Bill are compatible because

they do not engage any of the applicable rights or freedoms. The Government asserts

that Schedule 5 of the Bill engages the prohibition on arbitrary or

unlawful interference with privacy contained in Article 17 of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. However, the Government concludes

that Schedule 5 is consistent with Article 17 ‘on the basis that its engagement

of the prohibition on interference with privacy will neither be unlawful ... nor

arbitrary’.[15]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights considers

that the Bill does not raise human rights concerns.[16]

Schedule 1: concessional

loans involving tax exempt entities

Background—explanation

of the current law

Taxation of

tax exempt entities that are no longer tax exempt

A government owned entity is generally exempt from income

tax under Division 1AB of Part III of the ITAA 1936. However, in

recognition that the tax status of government owned entities can change (for

example where they are privatised),[17]

Division 57 of Schedule 2D to the ITAA 1936 contains specific

rules dealing with this scenario. Amongst other things, Division 57 of Schedule

2D contains rules that:

- allocate income and expenses against the pre-and-post transition

time according to when that income was earned or expense was incurred

- determine the tax cost of assets and liabilities of the entity,

including for the purposes of the Taxation of Financial Arrangements (TOFA)

rules and

- make balancing adjustments to the values of certain transferred

assets and liabilities, including for the purposes of the TOFA rules.

What are the

TOFA rules?

Australia’s TOFA rules are contained in Division 230 in

Part 3-10 of the ITAA 1997 and detail how taxpayers should treat gains

and losses on financial arrangements for tax purposes. The TOFA rules are

highly complex, but the following general points should be noted:

- the TOFA rules are based on the general premise that gains on

financial arrangements are assessable and losses are deductible over the life

of the arrangement[18]

- the concept of a financial arrangement is central to the TOFA

rules and is broadly defined in section 230-5 of the ITAA 1997 as one or

more cash settlable legal

or equitable rights and/or obligations to receive or provide a financial benefit

- subsection 974-160(1) of the ITAA 1997 defines a financial

benefit as anything of economic value, including

property or anything prescribed by regulation as being a financial benefit[19]

-

the TOFA rules do not apply to all taxpayers—as per section 230-5

of the ITAA 1997, a range of entities will mandatorily be subject to the

TOFA rules, including:

- an authorised deposit-taking institution, a securitisation

vehicle or a financial sector entity with an aggregated turnover of $20 million

or more

- a superannuation entity, a managed investment scheme or a similar

scheme under a foreign law if the value of the entity's assets is

$100 million or more

- any

other entity (except an individual) that has any of the following:

- an

aggregated turnover of $100 million or more

assets

of $300 million or more and

financial

assets of $100 million or more

entities that are not mandatorily subject to the TOFA rules may

elect to be subject to the TOFA rules.

The Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO) ‘Guide

to taxation of financial arrangements (TOFA)‘ provides a good explanation

of the TOFA rules in non-complex language.

Interaction

between Division 57 and the TOFA rules

Where a tax exempt entity subsequently becomes a taxable

entity, Division 57 of Schedule 2D to the ITAA 1936 requires that the

value of that entity’s assets and liabilities be set at their market value.[20]

As explained in the Explanatory Memorandum, government owned entities may be

able to obtain loans on more favourable terms than available in the market

place—meaning that for the purposes of Division 57, at the time of transfer,

the market value of the loan may be less than its face value.[21]

Where the relevant entity is covered by the TOFA rules,

the loan will constitute a financial arrangement and the difference between the

face value of the loan and its market value will be considered a ‘financial

benefit’. Under the TOFA rules, this difference will be treated as a loss, and

entitle the entity to a deduction equal to that difference for each year of the

loan-term. Conversely, where the difference between the face value of an asset

or liability and its market value gives rise to a gain, that gain will be

assessable on that difference for each year of the life of the financial

arrangement.[22]

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill states that this

outcome is not intended and the proposed amendments in Schedule 1 of the Bill are

necessary to address this integrity concern and protect the revenue base.[23]

The proposed amendments contained in Schedule 1 of the

Bill seek to address this concern, by ensuring that the interaction of Division

57 and the TOFA rules do not give rise to such unintended tax benefits or

liabilities by essentially resetting the values of the transferring assets and

liabilities to their market values at the time of their transfer.

Background

to the proposed amendment

Schedule 1 implements the measure ‘Company tax — Improving

the integrity of the tax treatment of concessional loans between tax exempt

entities’ announced in the 2018–19 Budget.[24]

Following the 2018–19 Budget, Treasury commenced a public consultation from 11

October 2018 to 2 November 2018 on the proposed changes.[25]

However, the Government has not published any submissions or the outcomes of

that consultation.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

The position of the non-government parties and

independents is not known, however, it appears that this Schedule was broadly

supported in the House of Representatives.[26]

Position of

major interest groups

The Government has not released the submissions received during

the Treasury consultation on this Schedule of the Bill.[27]

Of the twenty three submissions received by the Senate Economics Legislation Committee

none made substantive comments in relation to Schedule 1.

However, the CPA and Tax Justice Network noted that they were

generally supportive of the Bill, while the Council of Small Business

Organisations Australia (COSBOA) stated they saw no issue with Schedule 1.[28]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, Schedule

1 is expected to have ‘nil’ financial impact.[29]

Key issues

and provisions

As noted above, the effect of the proposed amendments in Schedule

1 is to amend the TOFA balancing adjustment rules to ensure any gain or loss is

not attributable to the concessional terms of the TOFA asset or liability.[30]

The operation of the amendments is well explained at pages

12 to 23 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill and includes a number of

worked examples.[31]

Application

The proposed amendments made by Schedule 1 of the Bill are

retrospective and apply from 7:30pm (ACT time) 8 May 2018. This aligns with the

timing of the announced changes in the 2018-19 Budget.[32]

Concluding

comments

Schedule 1 appears to be relatively uncontroversial and no

significant issues appear to have been raised by stakeholders.

Schedule 2: enhancing

the integrity of the small business CGT concessions

Background:

small business CGT concessions

Capital

Gains Tax

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) is a specific set of tax rules

relating to capital assets (for example, real estate or shares). Capital gains

tax is generally payable where the proceeds from an asset’s disposal (for

example, selling or assigning the asset) exceed the costs of acquiring and

maintaining it (known as the cost base). A capital loss occurs when the cost

base exceeds the proceeds from the asset’s sale.

Capital gains are added to an individual’s assessable

income and taxed at the relevant marginal tax rate. Where a taxpayer has a

capital loss, it can only be applied against capital gains—that is, it cannot

be used to reduce tax paid on salary and wages or similar earnings.

There are specific rules in Division 152 of the ITAA

1997 which reduce or exempt the capital gains tax paid in respect of CGT

events that occur in relation to small businesses.[33]

Eligibility

for the small business CGT concessions

Subdivision 152-A of the ITAA 1997 outlines the basic

conditions a taxpayer must meet in order to be eligible for the small business

CGT concessions. Broadly, the Subdivision provides that in order to access the

CGT small business concessions a CGT event must take place in relation to an active

asset and one of the following requirements must be satisfied:

- the taxpayer with the CGT event must be carrying on a business that

has aggregated turnover[34]

in the current or previous year of less than $2 million (known as a CGT small

business entity) [35]

- the net value of assets held by the taxpayer, its connected

entities, and its affiliates does not exceed $6 million[36]

- the taxpayer is a partner in a partnership that is a CGT small

business entity for the income year, and the relevant CGT asset is an interest

in an asset of the partnership[37]

or

- the taxpayer doesn’t carry on business but the CGT asset is used

in a business carried on by a small business entity that is the taxpayer’s

affiliate or an entity connected with it (passively held assets).[38]

For the purposes of the small business CGT concessions, an

active asset is an asset that is owned by the taxpayer and:

- is used, or is held ready for use in the course of carrying on

the business of the taxpayer, their connected entity or affiliates or

- is an intangible asset (for example, goodwill) owned by the

taxpayer that is inherently connected with the business of the taxpayer, their

connected entity or affiliates[39]

or

- is a share in an Australian resident company or an interest in a

resident trust, where the share or interest accounts for 80 per cent or more of

the market value of all assets held by the company or trust.[40]

Subsection 152-10(2) of the ITAA 1997 also lists

some additional basic conditions that must be satisfied if the CGT asset is a share

in a company or an interest in a trust.[41]

What are the

CGT small business concessions and how do they operate?

Division 152 of the ITAA 1997 creates four CGT

concessions for small businesses. These concessions apply in addition to

the 50 per cent CGT discount that applies to a CGT asset that has been held for

12 or more months.

While the small business 15-year exemption takes priority

over the other CGT small business exemptions, a taxpayer is otherwise able to

order and apply as many of the concessions as they are eligible for in order to

reduce their liability to nil. The four concessions are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: CGT small business concessions

|

CGT Concession

|

Description

|

|

Small

business 15-year exemption

|

Generally, an individual will be able to disregard a

capital gain where they continuously owned the CGT asset for 15 years prior

to its disposal and they are either:

- aged

over 55 and the CGT event happens in connection with their retirement, or

- they were

permanently incapacitated at the time of the CGT event.[42]

A trust or company will also be able to disregard a

capital gain where they continuously owned the CGT asset for 15 years prior

to its disposal and:

- there

was a ‘significant individual shareholder’ during the 15 year period (that

is, a person that has a 20 per cent or greater total direct and indirect

interest the company or trust)[43]

and

- the

significant individual shareholder was either:

- aged 55 or over and

the CGT event happens in connection with their retirement or

- they were

permanently incapacitated at the time of the CGT event.[44]

|

|

Small

business 50 per cent active asset reduction

|

This concession allows an eligible taxpayer to reduce a

capital gain on an active asset by 50 per cent. The taxpayer only needs to

satisfy the basic conditions outlined above under the heading ‘Eligibility

for the small business CGT concessions’.[45]

Section 152-200 of the ITAA 1997

lists the following ordering rules:

- The 15

year exemption takes priority, meaning the 50 per cent reduction does not

apply where the gain has already been disregarded under the 15 year

exemption.[46]

- If the

general 50 per cent CGT reduction has been applied, the small business

reduction will apply to that reduced amount.[47]

- The

capital gain can then be further reduced by the small business retirement

exemption and/or small business rollover.[48]

- A

taxpayer may elect to apply the small business retirement exemption and/or

small business rollover instead of the 50 per cent small business reduction.[49]

|

|

Small

business retirement exemption

|

An individual aged under 55 may over their lifetime disregard

$500,000 worth of proceeds from a capital gain where those proceeds are

contributed to a complying superfund or retirement savings account.[50]

This exemption also applies to the capital gains of a company

or trust where it has a significant individual shareholder and it makes a payment

to a shareholder that is a significant individual shareholder or the spouse of

a significant individual shareholder, provided the spouse has an interest of

greater than zero in that company or trust.[51]

|

|

Small

business rollover exemption

|

Generally the rollover exemption will apply when an active

asset has been sold and a replacement asset has been acquired. The

realisation of the capital gain is deferred until the replacement asset is

disposed.[52]

|

Source: Income Tax

Assessment Act 1997 and ATO, ‘Small

business CGT concessions’, ATO website.

Background:

Everett assignments

What is an Everett

assignment?

As noted above, the CGT small business concession can

extend to partners in partnerships. Generally, a partner will pay tax on their

share of partnership income,[53]

however in some instances, a partner may assign some or all of their interest

in a partnership. The consequence of this is the share of assigned income will

be taxable in the hands of the person who has received the assigned income rather

than the original partner—this arrangement is known as an ‘Everett

assignment’ flowing from the High Court decision of Federal Commissioner

of Taxation v Everett.[54]

An Everett assignment may be motivated by tax

minimisation purposes. This is because a possible effect of the assignment is

to re-allocate income from a taxpayer with a high marginal tax rate to one with

a lower marginal tax rate, meaning that the same amount of income now has an

overall lower level of tax paid. The operation of an Everett assignment is

illustrated by Example 1.

Interaction

between the CGT small business concessions and Everett assignments

The assignment of a partnership interest under an Everett

assignment will generally attract CGT because the partnership interest is a

CGT asset.[56]

Furthermore and as noted by the Explanatory Memorandum, Everett assignments fall

within the scope of the CGT small business concessions where the relevant

taxpayer satisfies the eligibility requirements set out above—that is, the

assignment of the partnership interest to another person results in a CGT

event, but in some instances the CGT small business concessions can apply and

result in a sizeable reduction in the amount of capital gains tax payable.[57]

It is important to recognise that Everett assignments are

but one strategy that can be employed to implement income splitting

arrangements—although an Everett assignment by itself will generally not be

found to be a tax avoidance arrangement, this may vary depending on the facts

and circumstances of a given case.

ATO view of

Everett assignments

Everett assignments have a long and complex history and

have been particularly popular amongst medical practitioners, dentists, lawyers

and accountants.[58]

The ATO’s attitudes towards their tax efficacy have also varied over time—for

example, in ATO Taxation

Ruling IT 2330 released in 1986 and ATO Taxation

Ruling IT 2501 issued in 1988, the ATO took the view that Everett

assignments were generally not tax avoidance arrangements. However, in

2015 the ATO varied its position concluding that an Everett assignment could

constitute a tax avoidance arrangement when one of the ATO’s pre-defined

benchmarks was not satisfied. The ATO has removed the Guidelines from their

website, however Tax & Super Australia has provided the following summary

of the ATO’s position:

The ATO says taxpayers will be rated as low risk and not

subject to compliance action if they meet one of the following guidelines

regarding income from the firm (including salary, partnership or trust

distributions, distributions from service entities or dividends from associated

entities):

- the practitioner receives assessable income from the firm in

their own hands as an appropriate return for the services they provide to the

firm. The benchmark for an appropriate level of income will be the remuneration

paid to the highest band of professional employees providing equivalent services

to the firm, or to a comparable firm

- 50% or more of the income to which the practitioner and their

associated entities are collectively entitled (whether directly or indirectly

through interposed entities) in the relevant year is assessable in the hands of

the practitioner

- the practitioner, and their associated entities, both have an

effective tax rate of 30% or higher on the income received from the firm.[59]

In 2017 the ATO announced they were suspending those

guidelines on the basis that they were being ‘misinterpreted in relation to

arrangements that go beyond the scope of the guidelines’.[60]

Background:

government announcement

Following the ATO’s suspension of the aforementioned guidance,

the Government announced in the 2018–19 Budget that from 8 May 2018:

partners that alienate their income by creating, assigning or

otherwise dealing in rights to the future income of a partnership will no

longer be able to access the small business capital gains tax (CGT) concessions

in relation to these rights.[61]

[emphasis added].

A subsequent public consultation process commenced on 12

October 2018, but to date, the Government has not published the outcomes of the

consultation or stakeholder submissions on the Treasury website.[62]

It is not clear whether the ATO’s 2017 decision to suspend

the guidelines and the Government’s subsequent budget announcement are related.

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee is concerned with the fact

that the proposed amendments apply retrospectively, that is, the changes apply

from the time they were announced on 8 May 2018—specifically, the Committee

considers:

- provisions that back-date commencement to the date of the

announcement of the Bill ‘challenges a basic value of the rule of law that, in

general, laws should only operate prospectively (not retrospectively)’ and

- in the context of tax law, the Committee is ‘concerned that

reliance on ministerial announcements and the implicit requirement that persons

arrange their affairs in accordance with such announcements, rather than in

accordance with the law, tends to undermine the principle that the law is made

by Parliament, not by the executive’.[63]

The Committee also notes that the Senate may decide to amend

the commencement date of taxation amendments in these circumstances:

Where taxation amendments are not brought before the

Parliament within six months of being announced, the bill risks having the

commencement date amended by resolution of the Senate (see Senate Resolution

No. 45). In this instance, the committee notes that it has been more than 12

months since the Budget announcement.[64]

The Committee has requested the Assistant Treasurer’s advice

as to:

- how many individuals will be detrimentally affected by the

retrospective application of the legislation, and the extent of their detriment

and

- the extent to which the Bill as introduced is consistent with the

measures announced on 8 May 2018.[65]

At the time of writing, the Committee has received the

Assistant Treasurer’s response, but the response has not yet been published.[66]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

The position of the non-government parties and

independents is not known, however, it appears that Schedule 2 was broadly

supported in the House of Representatives.[67]

Position of

major interest groups

In its submission to the Senate Economics Legislation Committee,

CPA Australia stated that it did not support the retrospective nature of the

amendments.[68]

CPA Australia also expressed concern that the amendments did not address the

more significant issue of service trust arrangements, stating that:

Issues relating to partnership assignments, service trusts

and professional services firms are not wholly resolved by the amendment to the

small business CGT concessions and further legislative and administrative

guidance is required to provide clarity and certainty to the industry...

The bigger issue for practitioners is in relation to service

trusts, as there is great uncertainty in the industry following both the ATO’s

withdrawal of its previous guidance and the delay(s) in issuing new guidance.[69]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the measure is ‘estimated

to result in a small but unquantifiable gain to revenue over the forward

estimates period’.[70]

Key provisions

Item 2 of Schedule 2 inserts proposed sub-section

152-10(2C) into the ITAA 1997. Proposed sub-section 152-10(2C)

will create a new basic condition that must be satisfied in order to access the

small business CGT concessions—namely:

where a CGT event arises in

relation to the creation, transfer, variation or cessation of a right or

interest that would entitle an entity to:

- an amount of the income or capital of a partnership or

- an amount calculated with reference to a partner’s entitlement to

an amount of income or capital of the partnership

the CGT small business

concessions will only be available where that right or interest is a membership

interest in the partnership.

The effect of this is that the assignment of

non-membership interests in partnerships will not be eligible for the small

business CGT concessions.

Application

The amendments made by Schedule 2 of the Bill will apply retrospectively

from 7:30 pm (ACT time), 8 May 2018 to align with the timing of the 2018-19

Budget announcement.[71]

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill:

Retrospective application is necessary as the amendments are

an important integrity measures to prevent inappropriate access to the CGT

small business concessions for arrangements undertaken to reduce partner’s tax

liabilities. If the amendments did not apply from announcement, partners would

be able to enter into such arrangements during the period between announcement

and the passage of legislation and avoid the operation of the measure.[72]

Concluding

comments

Schedule 2 appears to be relatively uncontroversial and no

significant issues appear to have been raised by stakeholders.

Schedule 3: limiting

deductions for vacant land

Background:

legislative requirements

General

deduction provisions

Expenses relating to vacant land are generally covered by

the general deduction provision contained in section 8-1 of the ITAA 1997 (the

general deduction provision). Section 8-1 of the ITAA 1997 provides that

a taxpayer will be entitled to a tax deduction where:

- the

relevant expense or outgoing was incurred in gaining or producing income, or

- it

was a necessary expense related to carrying on a business.[73]

However, an expense is not deductible under the general

deduction provision where it is:

- capital,

private or domestic in nature

- related

to producing exempt or non-assessable income or

- specifically

prohibited by the tax law.[74]

For example, interest repayments made in respect to a

rental property will be tax deductible as the interest repayment was made in

connection with deriving rental income. Conversely, interest repayments made in

respect of a taxpayer’s main residence will not be deductible as the interest

repayments are for a private or domestic purpose.

‘Carrying on

a business’

Whether an asset is held in the course of carrying on a

business is a question of fact and degree—as stated by Justice Hill in Evans

v Commissioner of Taxation ‘[t]he question

of whether a particular activity constitutes a business is often a difficult

one involving as it does questions of fact and degree’.[75]

The question of whether an asset is held for the purpose

of producing assessable income or in the course of carrying on a business can

become considerably more complex where the asset is vacant land held by an

individual. In Taxation Ruling TR

2019/1 Income tax: when does a company carry on a business (Taxation Ruling

2019/1) the ATO has stated that the derivation of passive income (such as rent

from property) by an individual does not give

rise to a presumption that an individual is carrying on a business, whereas it

would if those same activities are undertaken by a company.[76]

Specific

deduction provisions

In addition to the general deduction provisions, section

8-5 of the ITAA 1997 allows a taxpayer to claim a deduction for certain

things specifically provided for under the tax laws—these are known as ‘specific

deductions’ and are listed at section 12-5 of the ITAA 1997.[77]

Where an outgoing or expense is deductible under both the

general and specific deduction provisions, the taxpayer can deduct only under

the provision that is most appropriate (this means the specific deduction

provision will generally take priority).[78]

The proposed amendment in Schedule 3 creates a new specific deduction provision

which limits the circumstances in which expenses or losses associated with

holding vacant land may be deducted, thereby over-riding the general deduction

provisions that currently apply.

Background:

Policy rationale and drivers for the proposed amendments

The Government announced in the 2018–19

Budget that from 1 July 2019, certain deductions would be denied for

expenses associated with holding vacant land.[79]

It appears that the changes in the Bill are driven by three primary

considerations.

Land banking

The first consideration was raised in the Budget announcement,

which explicitly stated that this measure would reduce the incentives for land

banking practices that deny the use of land for housing or other development.[80]

However, the second reading speech and Explanatory Materials do not mention

land banking and the Bill has a large number of exemptions that may ultimately

limit its effectiveness at curbing land banking (as it excludes corporate tax

entities, super plans and managed investment trusts). Following the Budget

announcement some commentators labelled the measures, a new ‘land banking tax’,

including the Domain

Group.[81]

However, the Property Council of Australia did not share

these concerns, with chief executive Ken Morrison stating that he clarified the

Bill’s operation with the Treasurer’s office, and that in the vast majority of

cases development companies will not be affected by the announcement and it

will not be the ‘big bogey man for the industry that some have speculated’.[82]

Inappropriate

deductions

The second consideration is the Government’s assertion

that some taxpayers have been claiming deductions associated with holding

vacant land when they were not genuinely holding that land for the

purpose of gaining or producing assessable income or in the course of carrying

on a business.[83]

This concern was also specifically raised in the 2018–19 Budget, where it was

stated that deductions were being improperly claimed for expenses, such as

interest costs, related to holding vacant land where the land was not genuinely

held for the purpose of earning assessable income.[84]

ATO

administrative difficulties

On introduction of the Bill into Parliament an additional

consideration appears to have been noted—namely, compliance and administrative

difficulties faced by the ATO in denying the inappropriate deductions for vacant

land. As explained in the Explanatory Memorandum:

As the land is vacant, there is often limited evidence about

the taxpayer’s intent other than statements by the taxpayer. The reliance on a

taxpayer’s assertion about their current intention leads to compliance and

administrative difficulties.[85]

As discussed in more detail under the heading ‘Key issues and

provisions’, it is not clear the proposed amendments will address the above

concerns. In particular, it is not expected that compliance and administrative

difficulties will be reduced for the following reasons:

- a significant amount of businesses and taxpayers are exempted

from the new changes, meaning the existing, difficult to administer law

continues to operate for this class of taxpayers

- the new carrying on a business test is not necessarily clearer

than the current tests, particularly in the context of individuals (to whom the

proposed new rules will apply) and

- as noted by some stakeholders, some of the proposed amendments

may increase uncertainty and result in new and additional compliance and

administrative difficulties.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

The position of the non-government parties and

independents is not known, however, it appears that Schedule 3 was broadly

supported in the House of Representatives.[86]

Position of

major interest groups

The Government has not released the submissions received

during the Treasury consultation on Schedule 3 of the Bill.[87]

Of the twenty three submissions received by the Senate Economics Legislation

Committee, a small number directly discuss Schedule 3.[88]

Some of the issues raised in submissions to the Senate Economics Legislation

Committee are discussed in more detail below.

The

amendment may deny deductions earned in the course of deriving passive

assessable income

CPA Australia has raised concerns that there may be

situations where income is being earned by an individual from vacant land but they

are not carrying on a business. As discussed in Taxation

Ruling 2019/1 the derivation of rent from property by an individual does

not give rise to a presumption that an individual is carrying on a business. This

demonstrates the challenges with relying on the ‘carrying on a business’ test

in the proposed amendments and highlights how the objectives of the proposed amendment

may be undermined – namely:

- reducing

compliance and administrative complexities and

- preventing inappropriate deductions by targeting the amendment only

to arrangements that do not generate assessable income.

On this second point, CPA Australia set out a number of

situations where a non-exempted entity can earn passive income from vacant land

from unrelated third-parties, but be precluded from claiming a tax deduction in

respect of that income, including:

- an

agistment on vacant land

- allowing cars to park on vacant land and

- a

retired farmer leasing land to a third party.[89]

CPA Australia also raised concerns that deductions may be

denied where a farmer owns land over two titles and due to drought leaves one of

the land titles vacant as it is not economical to use that land.[90]

These views were also echoed by CAANZ, the Australian Small Business Family

Enterprise Ombudsman (ASBFEO) and MC Tax Advisors.[91]

CAANZ notes that it previously raised concerns with

Treasury that the proposed amendments should exclude any land that is used by a

third-party under a commercial arm’s-length lease arrangement. CAANZ notes this

will cover a range of situations, including farmers who have leased vacant land

without a permanent structure, such as land used for agistment or certain car

parking lots.[92]

The Explanatory Memorandum states one of the purposes of the amendment is to

deal with vacant land that is not genuinely held for the purpose of deriving

income; CAANZ notes that given this is the case it is not clear why deductions

can be denied for arm’s-length third-party arrangements.[93]

Impact on

farmers and small businesses

The ASBFEO specifically notes that the proposed amendment

preferences corporate structures and arbitrarily denies tax deductions for

non-corporate small businesses and self-managed super funds—according to ASBFEO,

almost two-thirds of small business are conducted via non-corporate structures.[94]

In their submissions, CAANZ, CPA Australia, MC Tax

Advisors and the ASBFEO also raise concerns that the proposed amendments may

unfairly target or disadvantage farmers that do not use corporate structures,

or derive passive income from land that does not have a permanent structure. CPA

Australia has also flagged that if a non-exempted entity does seek to become an

exempted entity by incorporating into a company to carry out the activities,

the ATO may seek to apply the General

Anti-Avoidance Rule in Part IVA of the ITAA 1936. [95]

That is, the ATO may take the position that the arrangement was entered into

for the sole or dominant purpose of obtaining a tax benefit.

It is important to also recognise that this amendment may

have broader impacts than just on farmers—that is, any non-exempted entity that

is using vacant land to derive income (be it passive or otherwise) and who is

not considered to be ‘carrying on a business’ may no longer be entitled to

deductions. For example, as reported by The Age in 2013, the ATO

launched a ‘crack down’ into whether thoroughbred horse breeders were carrying

on a business and/or have non-commercial losses. In the situation where the

breeders are deemed to not be carrying on a business and they have vacant land,

deductions incurred in relation to holding that vacant land (including for the

purpose of grazing or training) will not be deductible against any income

derived.[96]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, as at the 2018–19

Budget, in the forward estimates period the proposed measure was expected to

result in a gain to revenue of $25 million in each of 2020–21 and 2021–22.[97]

Key issues

and provisions

Summary

Item 3 of Schedule 3 inserts proposed section

26-102 in to the ITAA 1997. The provision limits the circumstances

in which a taxpayer can claim a deduction for expenses incurred in connection

with holding vacant land. Broadly, expenses for holding vacant land will not be

deductible unless:

- the

land is in use or available for use in ‘carrying on a business’ or

- the

taxpayer is a type of entity excluded by the changes.

Proposed section 26-102 does not apply to:

- land

that is not ‘vacant’

- vacant

land which is held in connection with ‘carrying on a business’ and

- certain

kinds of entities.

Special provision is also made for exclusion of

residential premises where they can be lawfully occupied and available for

lease.

The ATO provided a flow chart to the Senate Economics

Legislation illustrating the operation of the changes—the flowchart is

reproduced as an Appendix.

What is

vacant land?

Proposed section 26-102 of the ITAA 1997 limits

the availability of deductions for losses or outgoings relating to holding land

if there is no:

- substantial and permanent structure in use or available for use

on the land which has a purpose independent of, and not incidental to, the

purpose of any other structure or proposed structure or

- residential premises that is lawfully able to be occupied and is

either leased, hired or licensed, or available for lease, hire or licence.[98]

Substantial and

permanent structure

The terms ‘substantial’ and ‘permanent’ structure are not

defined in the proposed amendment and take their ordinary meaning. The Explanatory

Memorandum seeks to provide guidance on what is meant by these terms. For

example, the Explanatory Memorandum states that to be:

- substantial, a building needs to be significant in

size, value or some other criteria of importance in the context of the relevant

property—this is not stated in the proposed amendments but rather inferred from

the ordinary meaning of substantial and

- permanent, a structure needs to be fixed and

enduring—again, this is not explicitly contained in the proposed amendments.[99]

Further, the Explanatory Memorandum notes that whether a

structure has an independent purpose that is not incidental to the purpose of

another structure is a question of fact:

It needs to be considered in the context of the structure,

the land on which it is located and the other structures (if any) that have

been, are in the process of being or may be expected to be constructed on that

land.[100]

As such, what constitutes substantial, permanent, incidental

or independent is likely to be determined on a case-by-case basis and

ultimately a matter of interpretation for the courts. This is likely to create

further uncertainty around the application of the proposed amendments, undermining

one of the objectives of the proposed amendments.

Who can

deduct expenses for vacant land?

Proposed section 26-102 of the ITAA 1997 enables

a taxpayer to deduct a loss or outgoing incurred for vacate land if:

- the

land is in use or available for use in ‘carrying on a business’ or

- the taxpayer is a particular type of entity, irrespective of

whether they are using the land in carrying on a business.[101]

A taxpayer

who uses the land to carrying on a business

Proposed subsections 26-102(1) and (2) of

the ITAA 1997 state that an outgoing or loss in respect of land can only

be deducted to the extent that the land is in use, or available for use, in

carrying on a business for the purpose of gaining or producing assessable

income by the taxpayer or:

- their

affiliates

- their

spouse

- their

children aged under 18 or

- any

connected entities.

For taxpayers that are not excluded under proposed

subsection 26-102(5), it does not matter that they may be using vacant land

to produce assessable income and incur expenses—they will not be entitled to a

deduction unless they can demonstrate the land is in use or available for use

in carrying on a business.

Kinds of

taxpayers who can continue to deduct expenses as a general deduction

Proposed subsection

26-102(5) of the ITAA 1997 specifically excludes the

following taxpayers from the proposed amendment (excluded entities):

- corporate

tax entities

- superannuation

plans that are not self-managed superannuation funds

- managed

investment trusts

- public

unit trading trusts or

- unit

trusts or partnerships where each member is one of the above listed entities.

While these taxpayers are excluded from the operation of proposed subsection 26-102(1), they must still

satisfy the general deduction provision in section 8-1 of the ITAA 1997—namely,

that the loss or outgoing incurred in connection with holding vacant land is:

- incurred

in gaining or producing assessable income or

- necessarily incurred in carrying on a business for the

purpose of gaining or producing assessable income.[102]

Key issue: does

Schedule 3 achieve its objectives?

As discussed above, the primary issue with the proposed

amendments is whether Schedule 3 actually achieves its primary purposes. The

main purposes of Schedule 3 appear to be to:

- prevent

land-banking practices

- increase

certainty and

- reduce

compliance and administrative costs for the ATO.

Preventing

land banking

It is unclear how the amendment addresses the issue of

land-banking. For instance, the topic of land banking has not been discussed in

the Explanatory Memorandum and a Regulatory Impact Statement has not been

included. As such, there is no available information in the Bill or its

explanatory materials as to the number and kinds of taxpayers engaging in land

banking and whether they will be captured by the proposed amendments.

Increasing

certainty and reducing compliance and administrative challenges for the ATO

As discussed above, and as raised by stakeholders, it does

not appear that the proposed amendment will increase certainty or reduce the

compliance challenges for the ATO. The reasons for this are:

- The legislation introduces a number of new concepts that have not

been clearly defined in the proposed amendments. For example, it is not clear

when a structure on land will be ‘substantial’, or ‘have an incidental or

independent purpose’.

- The carrying on a business test is not a bright line test. As

noted by the Courts and Taxation Ruling TR

97/11 Income tax: am I carrying on a business of primary production?,

no single factor is decisive—in fact many factors overlap, and many go to a

taxpayer’s subjective intention.[103]

In many instances, there may be limited evidence about a taxpayer’s intention

other than statements by the taxpayer, a situation that the amendments are

seeking to expressly address.

- TR 2019/1 also creates additional uncertainty as it contains the

ATO’s view that the derivation of rental income by an individual does not

necessarily mean a business is being carried on. In many instances vacant land

will be generating passive rental income—it is not clear how the proposed

amendments provide non-exempted entities with additional certainty. If

anything, it may lead to increased compliance costs and administrative burden as

in each case the ATO and taxpayers will need to consider whether a business is

being carried on before making/disallowing a deduction against passive rental income.

Where the deduction is denied, the taxpayer will need to consider whether the

expense can be added to their CGT cost base (adding another layer of complexity).

- As raised by CPA Australia, there is doubt as to whether

incorporating an entity to hold vacant land may trigger the application of the General

Anti-Avoidance Rule in Part IVA of the ITAA 1936.

Application

The amendments apply to losses or outgoings incurred from 1

July 2019, regardless of whether land was first held prior to this date.[104]

Concluding

comments

Schedule 3 appears to be relatively controversial and it

is questionable whether it achieves its stated objectives of reducing land

banking, increasing taxpayer compliance and providing administrative certainty.

Schedule 4: extending

anti-avoidance rules to circular trusts

Background

What is a

circular trust distribution?

This proposed measure was announced by the Government in

the 2018–19 Budget as a tax integrity measure. The proposed amendments extend

the operation of particular anti-avoidance rules to family trusts which

currently apply to other closely held trusts. ATO Deputy Commissioner Jeremy

Hirschhorn describes the mischief the measure seeks to remedy as follows:

This provision addresses a particular problem. I might

explain the problem. If people have some investments or some earnings in a

trust, the trust does not pay tax on that income if it distributes it to

somebody else. It would distribute it to another trust and that trust would not

pay tax on that income as long as it distributes it to somebody else. But

somewhere along the line it starts the circle again. The argument of this

perhaps too-clever-by-half idea was that the money would keep spiralling and

nobody would ever pay tax on that income. This makes more comprehensive a

previous avoidance provision to stop that problem. It applies to the type of

scheme that involves a family trust. The previous measure did not apply where

it was a family trust... In the real world of cases, we have seen this used

rarely. But when somebody uses it, they use it for significant dollars.[105]

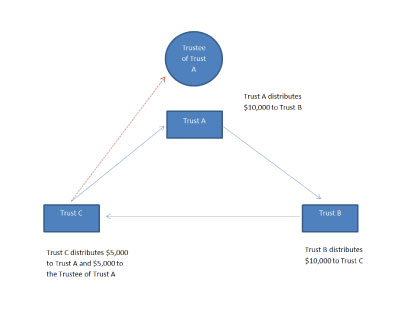

Diagram 1 illustrates how a circular trust distribution

operates.

Diagram 1: circular trust distribution

Source: Parliamentary Library

In the above example, all of the trusts are closely held

and the trustee of Trust A is made presently entitled to $5,000 of Trust C’s

trust income.[106]

The $5,000 is directly attributable to the trust income of Trust A. As noted by

the ATO Tax

Avoidance Taskforce, there may be a number of reasons for Trust A

redirecting income to the Trustee of Trust A through a circular trust

distribution, including:

- making it difficult for the ATO to identify who is the actual

recipient of a distribution (including the identification of who to impose tax

on)

- directing the distribution to a low taxed or preferentially taxed

entity that then redirects that income to the target beneficiary in a tax

effective manner—that is, a closely held entity with a tax loss (i.e. no tax

liability) may pass on a trust distribution in the form of an interest free

loan to the target beneficiary or

- directing the distribution to an entity that can re-characterise

that income—for example, income may be re-characterised as capital, so that a

target beneficiary with a capital gains loss may use that loss to reduce tax

payable on a distribution. [107]

What is

trustee non-disclosure beneficiary tax?

The trustee non-disclosure beneficiary tax is a specific anti-avoidance

rule that applies to certain circular trust distributions. The rules relating

to the trustee non-disclosure beneficiary tax are contained in Division 6D in

Part III of the ITAA 1936 and apply a higher penalty tax

(marginal tax rate plus the Medicare levy) where:

- there is a circular trust distribution involving closely held

trusts and

- there is a trustee beneficiary that is presently entitled to a

share of net income[108]

or

- the trustee fails to notify the ATO that a trustee beneficiary

has included a share of net income in their assessable income where that share

of net income includes an untaxed part.[109]

A closely held trust is defined as either:

- trusts in which up to 20 individuals have a fixed entitlement to

75 per cent or more of the income or capital of the trust or

- a discretionary trust.[110]

The trustee non-disclosure beneficiary tax does not apply

to excluded entities, which are currently defined to include family trusts.[111]

Key

provisions

Item 2 of Schedule 4 removes the following entities

from the definition of excluded entities:

- family trusts

- trusts for which an interposed entity election has been made[112]

and

- a trust that is part of a family group as per section 272-90 of

Schedule 2F to the ITAA 1936.[113]

The effect of this is that these trusts will be liable to

pay tax on the untaxed amount of a share of the net income of a trustee

beneficiary associated with a circular trust distribution.[114]

Items 3 and 4 of Schedule 4 insert proposed

paragraphs 102UK(1)(ca) and 102UT(1)(c) into the ITAA 1936. The

effect of these amendments is that the above listed entities are exempt from

the requirement to lodge a trustee beneficiary statement with the Commissioner.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill the amendments ‘do not

require a trustee of a family trust to lodge a trustee beneficiary statement

because it is considered that such reporting would impose unnecessary

compliance costs on family trusts’.[115]

Additional information about this amendment can be found

at pages 45 to 48 of the Explanatory Memorandum.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

The position of the non-government parties and

independents is not known, however, it appears that Schedule 4 was

broadly supported in the House of Representatives.[116]

Position of

major interest groups

The Government has not published the submissions received

during the Treasury consultation on this Schedule of the Bill.[117]

Of the twenty three submissions received by the Senate Economics Legislation Committee

only the Tax Justice Network made substantive comments in relation to Schedule 4.

While commending the Government on their willingness to extend the application

of the provisions to family trust, the Tax Justice Network:

... would have preferred that a trustee of a family trust be

required to lodge a trustee beneficiary statement with the Commissioner of

Taxation as applies to other trustees. The TJN-Aus is concerned that without

this requirement, how easy it will be for the ATO to detect round robin

arrangements involving family trusts.[118]

Application

The amendments in Schedule 4 apply in relation to income

years starting from 1 July 2019.[119]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, as at the 2018–19

Budget, the measure was estimated to result in a gain to revenue of $10 million

in each of 2020–21 and 2021–22.[120]

Concluding

comments

Schedule 4 appears to be relatively uncontroversial and no

significant issues appear to have been raised by stakeholders.

Schedule 5: disclosure

of business tax debts

Background:

current legislative requirements

Section 355-25 of Schedule 1 to the TAA makes it a

criminal offence for a taxation officer to make a record of or disclose protected

information. Section 355-155 makes it a criminal offence for an entity

(other than a taxation officer) to pass on, record or disclose protected

information acquired from a taxation officer. Protected information means information

that:

- was

disclosed or obtained under or for the purposes of a taxation law

- relates

to the affairs of an entity and

- identifies,

or is reasonably capable of being used to identify, the entity.[121]

The maximum penalty for these offences is two years

imprisonment.[122]

There are however a number of exceptions to these

offences, including, but not limited to:

- where

the disclosed information was already available to the public[123]

- disclosure was made by a tax officer in the course of performing their

duties as a tax officer[124]

or

- the disclosure was made to certain Government agencies and

officials in the circumstances listed in sections 355-55 to 355-65 in Schedule 1

of the TAA.[125]

Background: policy rationale

Schedule 5 seeks to implement the 2016-17 Mid-Year

Economic and Fiscal Outlook announcement that the Government would allow

taxation officers to disclose to credit reporting bureaus the tax debt

information of businesses that do not effectively engage with the ATO to manage

their tax debts.[126]According

to the announcement, the measure was initially going to apply to businesses

with tax debts of more than $10,000 that were at least 90 days overdue—the

Government considered that measure would result in businesses paying ‘taxation

debts in a more timely manner to avoid affecting their credit rating’.[127]

The Explanatory Memorandum explains the rationale for the

proposed amendment is to increase taxpayer engagement with the ATO, noting that

the amendments will:

- allow tax debts to be placed on a similar footing as other debts,

thereby increasing the incentives for businesses to pay their debts in a timely

manner

- incentivise business to engage with the ATO as failure to do so

will mean their tax debt could be disclosed, thereby adversely impacting their

credit rating

- reduce unfair advantages enjoyed by businesses that do not pay

their tax debts and

- contribute to more informed decision making by the business

community by enabling other businesses and credit providers to more accurately

assess a business’s credit worthiness.[128]

Schedule 5 proposes to achieve this by amending the TAA

so that it is no longer a criminal offence for taxation officers to disclose

the tax debt information of taxpayers to credit rating bureaus in certain

circumstances. However, it is important to understand that the proposed

amendments only create a legislative framework—that is, they do not comprise a

full set of rules and exceptions. Rather, the mechanism that will determine

whether a debt is disclosable or not will be a legislative instrument issued by

the Minister.[129]

As such, the proposed amendments do not expressly require that:

- the disclosure exception only apply to entities with tax debts in

excess of $100,000

- taxpayers engaging with the ATO will not have their debts

disclosed and

- debts can only be disclosed where they are more than 90 days

overdue.[130]

However, the Assistant Treasurer’s second reading speech

indicates that the Government intends for the scheme to operate within these

parameters.[131]

Number of taxpayers

affected

The ATO has advised the Senate Economics Legislation

Committee in an answer to a question on notice that based on the current

proposed exposure draft legislative instrument, around 5,000 businesses could

potentially have their tax debts reported to credit reporting bureaus.[132]

Key

provisions

Item 2 of Schedule 5 to the Bill inserts an

exception to the offence under section 355-25 of Schedule 1 to the TAA. Proposed

subsection 355-72 of Schedule 1 to the TAA states that section

355-25 will not apply where:

- a taxation officer makes a record for, or disclosure to a credit

reporting bureau

- the disclosure is made in relation to the tax debt of an entity

that belongs to a class of entities declared by legislative instrument by the

Minister made under proposed subsection 355-72(5)

-

the disclosure is made for the purpose of enabling a credit

reporting bureau to prepare, issue, update, correct or confirm an entity’s

credit worthiness—a credit reporting bureau is defined in proposed subsection

355-72(7) as an entity recognised by the Commissioner as an entity that

prepares and issues credit worthiness reports in respect of other entities[133]

and

- where the disclosure is made for a purpose other than updating,

correcting or confirming previously disclosed information, both:

- the

Inspector-General of Taxation (IGT) has been consulted and

- 21

days have passed since the entity was given notice of the proposed disclosure.

Proposed subsections 355-72(2) and (3) of Schedule

1 to the TAA require the Commissioner to notify an entity in writing

that the ATO intends to make a disclosure. The notice must also explain what

information will be disclosed, the amount of outstanding tax debt and how the

taxpayer can make a complaint about the information being disclosed. Further, proposed

paragraph 355-72(3)(e) requires notice to be served on the entity.[134]

What debts

are covered?

‘Tax debts’ is a defined term and includes the following:

- any amount due to the Commonwealth directly under a taxation

law, including any such amount that is not yet payable (known as primary

tax debts) and

- an amount that is not a primary tax debt,

but is due to the Commonwealth in connection with a primary tax

debt.[135]

On this point, the Explanatory Memorandum states that:

The information that may be disclosed must relate to a

taxpayer’s tax debt within the meaning of section 8AAZA of the TAA 1953. This

includes primary tax debts such as income tax debts, activity statement debts,

superannuation debts and penalties and interest charge debts, and secondary tax

debts such as amounts due under a court order.[136]

Which

entities are covered?

Proposed subsection 355-72(5) of Schedule 1 to the TAA

allows the Minister to declare one or more classes of entities as being

able to have their tax debt information disclosed. Proposed subsection

355-72(6) creates two pre-conditions on the Minister prior to issuing a

legislative instrument— namely that the Minister must:

- consult with the Information Commissioner in relation to matters

that relate to the privacy functions (within the meaning of the Australian

Information Commissioner Act 2010) and would be affected by the

proposed instrument and

- consider any submissions made by the Information Commissioner

because of that consultation.

It is important to note that the Minister is only required

to consult with and consider the recommendations of the Information

Commissioner. As such, there is no legislative obligation to follow the

Information Commissioner’s recommendations.

While the Bill does not ultimately define those taxpayers

who may be subject to tax debt disclosure, the legislative instrument which

deems such future classes of taxpayers will be a disallowable instrument and in

this respect, there will be a level of Parliamentary scrutiny.[137]

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill provides the following justification for

providing the Minster with such a power:

Specifying the class of entity in a legislative instrument

provides the Government with flexibility to update the criteria promptly to

ensure it delivers the right policy outcome. It also provides an appropriate

level of Parliamentary scrutiny around the criteria as the instrument will be

disallowable.[138]

What is the proposed

class of taxpayers captured?

Proposed class

of taxpayers

On 24 July 2019, the Government released the Taxation

Administration (Tax Debt Information Disclosure) Declaration 2019 as an

Exposure Draft (the Exposure Draft Instrument).[139]

Under the Exposure Draft Instrument, the class of taxpayers captured is broadly

defined as taxpayers carrying on a business or similar venture with total tax

debts exceeding $100,000 that have been due for more than 90 days.

Specifically, proposed subsection 6(1) of the

Exposure Draft Instrument states that an entity must meet the following

criteria to be within the declared class of entities under proposed subsection

355-72(5) of Schedule 1 to the TAA:

- the entity is registered in the Australian Business Register and

is not a Deductible Gift Recipient, complying superannuation fund, registered

charity or government entity

- the entity has one or more tax debts, the total of which is at

least $100,000, that have been due and payable for more than 90 days and

- the entity satisfies either of the following:

- the

entity does not have an active complaint with the IGT concerning

the disclosure of tax debt information of the entity that is, or could be, the

subject of an investigation under paragraph 7(1)(a) of the Inspector-General

of Taxation Act 2003

- the

entity has an active complaint with the IGT, but after taking reasonable

steps to confirm whether the IGT has such a complaint, the Commissioner does

not become aware of the complaint.[140]

Consultation closed on 21 August 2019, however, it is not

clear whether the outcomes of consultation will be released before the Senate considers

the Bill. The proposed amendments were previously released for consultation by

Treasury in January 2018.[141]

At that time, the tax debt threshold defining the class of entities who could

be subject to disclosure was much lower, at $10,000.[142]

Non-disclosable

debts

Proposed subsection 6(2) of the Exposure Draft Instrument

seeks to exclude certain debts from counting towards the $100,000 debt amount.

These include debts in respect of which a taxpayer has:

- entered into a payment arrangement under section 255-15 of Schedule

1 to the TAA and the taxpayer is complying with that arrangement

- lodged a taxation objection and the commissioner has not made an

objection decision

- applied to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) for review

of, or appealed to the Federal Court against an objection decision and

proceedings have not been finalised

- requested a reconsideration of a reviewable decision under the Superannuation

Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SIS Act) in relation to the tax

debt and the decision has not been confirmed, revoked or varied

- applied to the AAT under the SIS Act for review of a decision

in relation to the tax debt and proceedings have not been finalised or

- an active complaint with the IGT in relation to the tax debt that

is, or could be, the subject of an investigation by the IGT and the Commissioner

becomes aware of the complaint.[143]

What

safeguards exist?

As noted above, the proposed amendments seek to create a

number of safeguards to limit the circumstances in which a disclosure can be

made.

Notice

required to be provided to the taxpayer

Before the ATO makes the initial disclosure, the entity

must be served with written notice by the Commissioner, which:

-

explains the type of information that is proposed to be disclosed

to the credit reporting bureau

- sets out the amount of any tax debts payable by the entity at the

time the notice is given by the Commissioner and

- explains how the primary entity may make a complaint in relation

to the proposed disclosure of the entity’s information.[144]

Commissioner

must consult with the IGT

Proposed paragraph 355-72(1)(e) of Schedule 1 to the

TAA requires the Commissioner to consult with the IGT prior to making a

disclosure of information (other than a disclosure which merely updates or

corrects a previous disclosure).

This requirement is intended to operate as a safeguard to

ensure that the Commissioner does not disclose the tax debt information of an

entity inappropriately.[145]

However, Schedule 5 does not contain any further information about consultation—it

merely requires the Commissioner to consult. On this point, the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill states that Minster’s legislative instrument may impose

further requirements regarding the IGT’s involvement in the process:

For example, the legislative instrument may only permit a

disclosure where the Inspector-General of Taxation has not advised that it is

conducting such an investigation relating to the taxpayer’s tax debt or the

Commissioner’s intention to disclose the taxpayer’s tax debt information. In

order to rely on the exception to the offence protecting the confidentiality of

tax information, taxation officers will be required to take reasonable steps to

confirm that such an investigation is not underway before making the

disclosure.[146]

While the EM considers that this provided operational

flexibility, it is questionable why fundamental safeguards are not included in

the Bill.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

The position of the non-government parties and

independents is not known, however, it appears that this Schedule was broadly

supported in the House of Representatives.[147]

Position of

major interest groups