Introductory Info

Date introduced: 21 June 2018

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: Sections 1 to 3 commence on Royal Assent. Schedules 1, 2 and 3 commence the day after Royal Assent.

Bills

Digest at glance

What the Bill does

The Treasury Laws Amendment (Protecting Your

Superannuation Package) Bill 2018 contains three Schedules, the purpose of

which is to make amendments to the SIS Act and the SUMLM Act to:

- limit

the amount of fees that can be charged by a trustee of a superannuation fund

for MySuper or choice products to three per cent of the balance of the account

if the balance is less than $6,000

- prohibit

superannuation funds and approved deposit funds from imposing exit fees when a

member disposes of all or part of their interest in a fund

- prevent

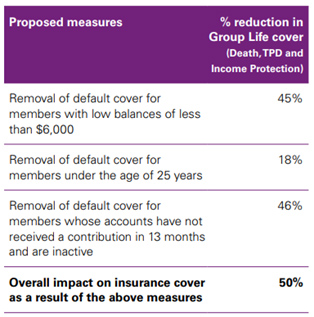

superannuation funds from providing insurance such as death, total and

permanent disability or income protection insurance on an opt-out basis where:

- the

member is under the age of 25 years and begins to hold a new superannuation

account on or after 1 July 2019

- the

member’s account balance falls below $6,000 or

- the

member’s account has not received a contribution for 13 months and is inactive

- require

retirement savings account providers and superannuation providers to pay the

balance of MySuper or choice accounts to the Commissioner of Taxation, where

the account is inactive and the balance is less than $6,000 and

- require

the Commissioner to consolidate any amounts received into a person’s

superannuation account that will have a balance of $6,000 or more once

consolidated.

Background

- The

measures contained in the Bill were announced by the Government in the 2018–19 budget

and form part of its ‘Protecting Your Super Package’.

- The

Productivity Commission released its draft report Superannuation:

Assessing Efficiency and Competitiveness following the 2018–19 budget.

Committee consideration

- The

provisions of the Bill were referred to the Senate Standing Committee on

Economics (Legislation Committee) for inquiry and report. The Committee

recommended that the Bill be passed by the Senate.

- ALP

Senators provided additional comments to the Committee’s report in which they

stated that they would continue to evaluate possible amendments.

Stakeholder views

- The

majority of stakeholders support the Government’s objective which is to prevent

the erosion of low-balance accounts due to excessive fees and insurance. In particular,

while some stakeholders have expressed their full support for the Bill, other

stakeholders do not agree with particular aspects of the Bill.

- Key

concerns include:

- the

proposed fee cap may lead to an reallocation of fees and charges to members who

have account balances that are greater than $6,000

- the

proposed commencement date of 1 July 2019, particularly in relation to Schedule

2 of the Bill, will be challenging for super funds to meet and could lead

to adverse outcomes for members

- the

proposed changes to opt-out insurance may impact high risk occupations

- the

13 month definition of inactivity may cause detriment to certain groups,

including for example, those taking parental leave and/or intermittent workers

- removing

opt-out insurance coverage for active members with balances below $6,000 means

that actively contributing members will not be covered for a period of time

unless they voluntarily opt-in

- the

age threshold of 25 years, being the age at which opt-out insurance can be

provided for new members, may be too high and may result in members who are

under 25 years old and who have dependants and/or liabilities being uninsured

- although

the precise amount is debated, insurance premiums are likely to increase both

because the insurance risk pool will be reduced and because high risk members

are more likely to opt-in and

- ensuring

that the ATO consolidates inactive accounts within an appropriate timeframe.

Other issues

- An

inconsistency appears to arise under proposed paragraph 99G(1)(b) of the

SIS Act which ‘switches-on’ the three per cent fee cap provisions if, on

the last day of the income year of the fund, the member has an account balance

that is less than $6,000. Example 2.4 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill

makes it clear that it is intended that the fee cap provision applies if a

member has a low balance account and closes their account before the last day

of the fund’s income year. However, the wording of proposed paragraph

99G(1)(b) does not make this particularly clear and may limit the application

of the provision to a member who holds the product for only part of the income

year, if they have a low balance account on the last day of the income year of

the fund—but not if there was no account on that day. In latter case, it is

possible that the fee cap in proposed section 99G of the SIS Act may

not apply.

- There

also appears to be a very minor error in the application clause in Part 2

of Schedule 3 to the Bill which makes reference to paragraph 20QA(1)(a)

‘as inserted by item 8 of this Schedule’. It is likely that the reference

should be to item 30 of Schedule 3.

Purpose of

the Bill

The Treasury Laws Amendment (Protecting Your

Superannuation Package) Bill 2018 (the Bill) makes amendments to the Superannuation

Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SIS Act) to:

- limit

the amount of certain fees that can be charged by a trustee of a superannuation

fund for MySuper or choice products to three per cent of the balance of the

account if the balance is less than $6,000

- prohibit

superannuation funds and approved deposit funds from imposing exit fees when a

member disposes of all or part of their interest in a fund and

- prevent

superannuation funds from providing insurance such as death, total and

permanent disability or income protection insurance on an opt-out basis where:

- the

member is under the age of 25 years and begins to hold a new superannuation

account on or after 1 July 2019

- the

member’s account balance falls below $6,000 or

- the

member’s account has not received a contribution for 13 months and is inactive.

The Bill also amends the Superannuation

(Unclaimed Money and Lost Members) Act 1999 (SUMLM Act) to:

- require

retirement savings account (RSA) providers and superannuation providers to pay

the balance of MySuper or choice accounts to the Commissioner of Taxation (the

Commissioner), where the account is inactive and the balance is less than

$6,000 and

- require

the Commissioner to consolidate any amounts received into a person’s

superannuation account that will have a balance of $6,000 or more once

consolidated.

The Bill also makes consequential amendments to the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA97) and the Taxation

Administration Act 1953 (TAA).

Structure

of the Bill

The Bill consists of three Schedules:

- Schedule

1 of the Bill bans exit fees on withdrawals and limits the amount of fees

that can be charged for MySuper or choice products where the balance of an

account is less than $6,000

- Schedule

2 of the Bill prevents insurance being provided on an opt-out basis in

certain circumstances and

- Schedule

3 of the Bill requires inactive low-balance accounts to be paid to the Australian

Taxation Office (ATO) and requires the ATO to consolidate any amounts received

into a superannuation account, the balance of which once consolidated will be

at least $6,000.

Structure of this Bills Digest

The relevant background, stakeholder comments and analysis

of the provisions are set out under each Schedule number.

Background

The 2018–19 Budget contained the Government’s ‘Protecting

Your Super Package’, which is intended to ‘protect individuals’ retirement

savings from undue erosion, ultimately increasing Australians’ superannuation

balances’.[1]

Consultation

Accordingly, on 8 May 2018, the Minister for Revenue and

Financial Services, Kelly O’Dwyer released an exposure draft of the current

Bill for public consultation.[2]

At that time she reiterated that the Government was seeking to protect

retirement savings ‘by introducing new measures to guard against the undue

erosion of superannuation balances through excessive fees and inappropriate

insurance arrangements’.[3]

Consultation ran until 29 May 2018 in which time Treasury

received 45 submissions.[4]

Productivity

Commission

Following the announcement of the Protecting Your Super

Package in the 2018–19 Budget, the Productivity Commission (PC) released its

draft report Superannuation:

Assessing Efficiency and Competitiveness (PC Draft Report) on 29 May

2018.[5]

In summary, the PC opined that the erosion of members’

balances is ‘substantial in size and regressive in impact’.[6]

The most substantial contributor to the erosion of member accounts are members

with multiple accounts which comprise a third of all accounts (about 10

million) and erode member balances by $2.6 billion per year in fees and

insurance.[7]

Further consideration of the recommendations made by the PC are set out under

each Schedule heading.

Committee

consideration

Senate

Standing Committee on Economics

The provisions of

the Bill were referred to the Senate Standing Committee on Economics (Legislation

Committee) for inquiry and report by 13 August 2018.[8]

Details of the inquiry are at the inquiry

homepage (the Committee inquiry). The Committee received 34 submissions as

well as additional information and answers to questions on notice. The

Committee also held a public hearing on 20 July 2018. The Committee delivered its

report into the inquiry to the Senate on 13 August 2018.[9]

The Committee recommended

that the Bill be passed by the Senate.[10]

While the Committee acknowledged a range of concerns which

had been raised by stakeholders,[11]

it ultimately considered that the Bill is ‘an important first step’ in

addressing the erosion of members’ balances as a result of fees and insurance,

and that the proposed measures ‘will have tangible benefits for Australians'

retirement savings’.[12]

Australian Labor Party (ALP) Senators provided additional

comments to the Committee’s report, in which they stated that they ‘are

cautiously supportive of the bill's broad objectives ... and will continue to

evaluate possible amendments in order to improve the legislation’.[13]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

had no comment on the Bill.[14]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

At the second reading of the Bill, ALP gave ‘qualified

support to the passage of the Bill through the House’, subject to the findings

of the Committee, Chris Hayes, MP stated:

Our position on this bill will be subject to the findings of

the Senate Economics Legislation Committee. We want to make sure that this bill

delivers what it purports to do and that there are no unintended consequences.[15]

Specifically, ALP Senators noted the following concerns

that had been raised by stakeholders:

- the

proposed fee cap may enable ‘funds to simply reallocate fees and charges’.[16]

The ALP Senators recommended that Treasury or the Australian Prudential

Regulation Authority (APRA) should monitor funds’ responses to the measure.[17]

Similarly, the Committee suggested that consideration be given to regulatory

monitoring of any changes with respect to buy-sell spread practices[18]

- the

proposed commencement date of 1 July 2019 for the changes to insurance

arrangements was particularly concerning for a broad range of stakeholders

- the

proposed changes to opt-out insurance may impact high risk occupations

- the

‘strict’ 13 month definition of ‘inactivity’

- removing

opt-out insurance coverage for active members with balances below $6,000

- the

age threshold of 25 years, being the age at which opt-out insurance can be

provided for new members

- the

potential ‘anti-selection’ problem that may result from the proposed

changes—that is, high risk people are more likely to opt-in which may increase

the average risk of the pool and

- ensuring

that the ATO consolidates inactive accounts within an appropriate timeframe.[19]

ALP Senators also considered that it was ‘unusual’ for the

Government to be proceeding based on the PC’s Draft Report, and noted the Royal

Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial

Services Industry had only recently begun looking at superannuation and

insurance arrangements within superannuation—its interim

report was submitted to the Governor-General and tabled in Parliament on 28

September 2018.[20]

ALP Senators noted that further changes may be required in the near future.

In a bid to increase women’s superannuation, the ALP

subsequently announced that, if elected, it would among other things:

While the ALP’s announcement does not propose any

amendments to the Bill, it is likely to result in a reduced number of

superannuation accounts being deemed to be ‘inactive’ for the purposes of

proposed Schedules 2 and 3 of the Bill. In particular, the payment of superannuation

on Commonwealth Paid Parental Leave and Dad and Partner Pay means that that for

the period it is paid, a superannuation account will not be considered to be

‘inactive’. Similarly, the phase out of the $450 minimum monthly threshold for eligibility

for the superannuation guarantee will result in a greater number of

superannuation accounts receiving contributions; this is likely to reduce the

number of accounts considered to be inactive because each contribution will

‘reset the clock’ on the 13 month period of inactivity.

Financial

implications

For the

Government

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the measures are

estimated to have a gain to the budget of approximately $850 million in fiscal

balance terms and around $1,750 million in underlying cash balance terms over

the forward estimates.[22]

For

business and individuals

A regulation impact statement (RIS) was prepared in

relation to the measures in the Bill. The amendments are expected to have a

regulatory cost of $28.5 million to business and $71.4 million to individuals averaged

over ten years.[23]

Stakeholder

comments

However, the Association of Financial Advisors (AFA)

consider that the ‘RIS has failed to adequately address the consequences of

these reforms’ and in particular that the ‘initial impact will be a significant

reduction in revenue for superannuation fund and insurers’, which will require

a reduction or redistribution of costs leading to premium increase and

potential job losses within the industry’.[24]

Rice Warner and AIA Australia (AIAA) also argued that the

collective impact of the proposed reforms would be higher than the Government

has estimated—being ‘an annual cost of $2.46 billion to the Government and the

Australian economy.’[25]

Of concern is the potential for decreased taxation revenue both at the

Commonwealth and state and territory level through the collection of income tax

on claim payments or state and territory levied stamp duty.[26]

It is also argued that the reduced insurance coverage will result in increased

reliance on social security payments.[27]

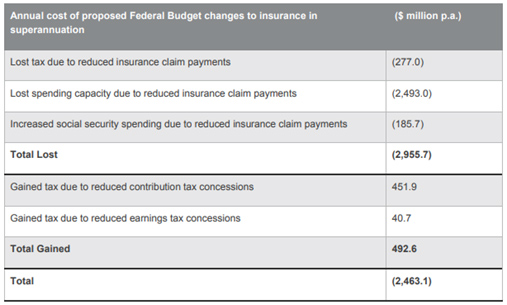

AIAA submitted the following table which, according to AIAA, outlines the

additional cost to Government and the economy.

Table 1: Additional cost to Government and the economy

Source: AIAA, Submission, p. 13.

However, at least in relation to the impacts of Schedule

2 of the Bill, the RIS states that ‘resulting impacts on Government

payments were factored into the overall cost of these measures as

published in Budget Paper Number 2, 2018–19’ (emphasis added).[28]

The 2018–19 Budget estimated that the cost to the

Department of Social Services amounted to $64.8 million over the forward

estimates.[29]

The Department of Social Services provided the following basis for the

estimate:

Based on data provided by the Treasury, the Department of

Social Services estimated over the forward estimates that an additional 1,482

people would receive Disability Support Pension; 4,799 people would receive

Newstart Allowance or Sickness Allowance, both of which will become the new

JobSeeker Payment from 20 March 2020; and 159 people would receive Youth

Allowance (other). This includes people receiving a part-rate of payment.[30]

Treasury also stated that the broader fiscal impacts had

been taken into account:

... the costing for the insurance changes included in the

budget materials took account of broader impacts on the government's social

security payments—for example, impacts on the cost of DSP and NDIS payments.

The impact on DSP payments was small, particularly in comparison with the

savings in the form of reduced tax concessions, and was taken into account in

the overall costing of the package. As there are no income or assets tests for

NDIS, there is likely to be negligible, if any, impact on the NDIS from the

changes to insurance in super.[31]

Statement of Compatibility

with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[32]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

considered that the Bill does not raise any human rights concerns either because

the Bill does not engage or promote human rights, and/or permissibly limits

human rights.[33]

Schedule 1—fees

charged to superannuation members

Commencement

While Schedule 1 of the Bill commences the day

after Royal Assent, the amendments apply in relation to fees and other amounts

in relation to years of income of a regulated superannuation fund ending on or

after 1 July 2019.[34]

Background

Employers are obliged to provide most employees with the

right to choose the superannuation fund into which their compulsory

superannuation guarantee contributions are made. This is called the choice of

fund requirement.

Broadly speaking, an employer satisfies the choice of fund

requirement by either making contributions to a fund chosen by the employee or,

where no choice is made, by contributing to its default fund.[35]

Only MySuper products are eligible as default funds.[36]

MySuper products were introduced by the Superannuation

Legislation Amendment (MySuper Core Provisions) Act 2012 and are governed

by Part 2C of the SIS Act. [37]

These products replaced the pre-existing default superannuation products in

order to provide consumers with a ‘simple and cost-effective superannuation

product’ that ‘have a simple set of product features, irrespective of who

provides them’.[38]

According to the Productivity Commission:

Over half of all accounts are in MySuper products (mostly

with not-for-profit funds), though these products only account for a quarter of

assets in APRA-regulated funds. Average balances for choice accounts are over

twice those of MySuper accounts, and accounts in [self-managed super funds] SMSFs

are about seven times as large again.[39]

About fees

The PC Draft Report makes the point:

Fees matter — they directly detract from members’ returns

and, ultimately, their retirement incomes. Higher fees of just 0.5 per cent a year

could reduce the retirement balance of a typical worker starting work today by

around $100 000.

In 2017, members of APRA-regulated funds collectively paid

$8.8 billion in fees (excluding insurance fees and premiums). In dollar terms,

fees per member account rose over the preceding decade, largely due to account

consolidation (reducing a regressive cross subsidy) and higher balances

(corresponding to higher investment costs).[40]

The types of fees paid by members to funds may include:

- administration

fees—which can be levied as a dollar charge over time (for example per month)

or as a percentage of a member’s assets

- investment

fees—which are typically levied as a percentage of a member’s assets

- insurance

fees—the cost of administering any insurance policy that is on a member’s

account

- specific

service fees—such as switching fees, withdrawal fees and fees for financial

advice (which are levied based on a member’s individual activities).[41]

Of these, administration and investment fees represent the

majority of fees charged by funds. These fees are incurred by members simply by

virtue of holding a product and are a significant cause of account balance

erosion, particularly for inactive accounts.[42]

The PC Draft Report states:

Higher fees are clearly associated with lower net returns

over the long term. The material amount of member assets in high-fee funds

(about 10 per cent of total system assets), coupled with persistence in fee

levels through time, suggests there is significant potential to lift retirement

balances overall by members moving, or being allocated, to a lower-fee and

better-performing fund.[43]

The Minister noted that regulatory protection for low

balance accounts was removed in 2013 with the introduction of MySuper.[44]

‘Member protection’ generally prevented trustees from charging administrative

fees that exceed the investment return on the account, where the balance of the

account was less than $1,000.[45]

The removal of member protection was recommended by the Super System Review

(the Cooper Review).[46]

The PC also noted in its Draft Report that it considered whether the member

protection rebate should be reinstated, but decided that reducing the ‘lost

inactive’ threshold from five to two years ‘would be reasonably effective at

minimising erosion on low-balance accounts, without enacting a cross-subsidy

from higher-balance accounts’. [47]

Another type of fee is an exit fee:

Generally, exit fees are levied as fixed dollar amounts,

ranging from small nominal amounts up to around $180 in 2016. For the average

MySuper member, exit fees are 0.1 per cent of assets, or $50 for a

representative member with a $50 000 balance. For choice members, average exit

fees are around double this, at 0.2 per cent of assets, or $100 for a

representative member.[48]

In addition, in some cases, exit fees can be charged as a

proportion of assets, which can be very high. According to the PC Draft Report,

there is ‘no justifiable basis for variable exit fees levied as a proportion of

a member’s assets’.[49]

The PC Draft Report recommended that ‘the Australian

Government should legislate to extend MySuper regulations limiting exit and

switching fees to cost-recovery levels to all new members and new accumulation

and retirement products’.[50]

Key provisions—caps on fees and costs

Three per

cent cap on low balances

Item 18 of Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the

Bill inserts proposed section 99G into Part 11A of the SIS Act to

limit the amount of fees that can be charged by the trustee of a regulated

superannuation fund which offers a choice or MySuper product, where the balance

of the account is less than $6,000 on last day of the income year of the fund.[51]

Member

holds product for the whole year

If the member holds the product for the whole year, the capped

fees and costs that can be charged by the fund (the ‘fee cap’) must not

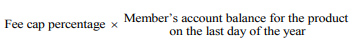

exceed the amount worked out in accordance with the following formula:[52]

Member

holds product for part of the year

If the member holds the product for only part of the income year, the fee cap

is worked out in accordance with the formula under proposed subsection

99G(5) and ‘apportioned based on the number of days the member held the

account during the income year’.[53]

The Superannuation

Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994 (SIS Regulations) may set a fee

cap percentage of no more than three per cent—that is, the cost and

fees will be unable to exceed three per cent of the member’s account balance.[54]

Member’s account balance for the product on the last day of the year

means so much of the member’s account balance with the fund on that day as

relates to the product.[55]

Item 14 of Part

1 in Schedule 1 to the Bill inserts proposed paragraph 31(2)(dc)

into the SIS Act which enables the SIS Regulations to stipulate rules

for the calculation of the member’s account balance. According to the

Explanatory Memorandum, such standards ‘will be used where necessary to provide

guidance on the treatment of amounts that have not been credited or debited to

account balances at the point of the calculation’.[56]

Nature of

fees and costs that are capped

The fees and costs

that are capped are listed in proposed subsection 99G(3) as, broadly,

administration and investment fees charged to the member in relation to the

product for the year, and any amount worked out in accordance with the SIS

Regulations that:

- is

not charged to the member as a fee

- is

incurred by the trustee of the fund in relation to the year and

- relates

to the administration of the fund or the investment of the assets of the fund.[57]

In order to reduce the compliance impact of the measure,

the superannuation fund is taken to have complied with the proposed fee cap on

low balance accounts if the fund refunds any amount that exceeds the fee cap to

the member within three months after the end of the year, or from the day the

member ceases to hold the account.[58]

Under section 99E of the SIS Act a trustee is

required to attribute the costs of the fund between the classes fairly and

reasonably. Adherence to proposed subsection 99G could be interpreted as

conflicting with the obligation under section 99E. Accordingly, proposed

subsection 99G(7) confirms that compliance with proposed subsection 99G will

not be in breach of section 99E of the SIS Act.

Items 2, 9, 10, 11 and 13

of Schedule 1 to the Bill make other necessary amendments to Part 2C of SIS

Act, which governs MySuper products, to give effect to the proposed

amendments.

Stakeholder

comments—fee caps

While many stakeholders are supportive of the cap on low

balance accounts, a range of stakeholder’s considered that the cap as set out

in the Bill is likely to produce unintended consequence and anomalous outcomes.

Potential

redistribution of fees

Some stakeholders considered that it was likely to result

in a redistribution of costs to those with account balances greater than

$6,000, or alternatively lead to a reduction in services for those members with

lower account balances. For example, AFA submitted:

The cost of running a superannuation fund and providing

services to members has a large fixed cost element, a fixed member level cost

and some level of costs that are variable based upon the services provided to

individual members. Whilst we understand the rationale for this proposal, the

consequences for those other members who will be subsidising those with low

balances needs to be considered.

The practical reality is that a fair and reasonable

allocation of costs within a superannuation fund will indicate that low balance

accounts are almost as expensive to maintain as high balance accounts.[59]

Rest Industry Super agreed that this may be an outcome.[60]

Deputy Chairman of APRA, Helen Rowell, stated that APRA

supported the ‘policy intent of the proposals’ and considered:

The proposal to limit the fees that can be charged to members

with balances under $6,000 will also require funds to review their fee

structures, and both of these measures may lead to higher fees for members with

balances over $6,000.[61]

ISA considers that in the absence of proposed regulations

being made available outlining the Government’s view on indirect fees, an

amendment should be made to the Bill to include such a definition to ensure

consistent application of the fee cap, stating:

... the supporting regulation is not available for review and

there are already significant gaps and inconsistencies in how funds report data

on fees and costs. This measure may further exacerbate the current lack of

transparency in fee disclosure. For example, it would be unacceptable if the

costs associated with interposed vehicles were capped, but investments made

through platforms were not. This would result in increasing opacity in fee

reporting and ultimately lower net returns for members whose savings are invested

in listed assets compared with unlisted assets. ISA is concerned that the

Bill’s objectives will not be achieved because of the imprecise nature and

vague context of these changes.[62]

Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees (AIST)

considered that ‘the preferable course of action should be to await the outcome

of the expert review of fees and costs’.[63]

AIST is referring to the external review by Darren McShane into Regulatory

Guide 97: Disclosing fees and costs in PDSs and periodic statements.[64]

According to ASIC, ‘RG 97 sets out ASIC's guidance on how to disclose fees and

costs in product disclosure statements and periodic statements for

superannuation funds and managed investment schemes.’[65]

The report, REP

581 Review of ASIC Regulatory Guide 97: Disclosing fees and costs in PDSs and

periodic statements, was released on 24 July 2018.[66]

It is beyond the scope of this Digest to consider this report, however, the

report does note that its ‘recommendations and observations ... have been made

without regard to the details of changes that might flow from the government’s

“Protecting Your Super” Package.’[67]

Timing of

the fee cap calculation

As noted above, the fee cap is based on the member’s

account balance on the last day of the income year or the last day on which the

member holds the account. AIST and other stakeholders considered that because proposed

section 99G does not take the member’s account balance for the previous 12

months into account, members could simply move funds out of the account prior

to the balance day in order to have their account fees capped.[68]

Fee cap

applied at the account or product level

Stakeholders also submitted that it was not clear whether

the fee cap is determined based on the member’s product balance, or their

account balance (in the event that they hold multiple products).[69]

The LCA submitted:

The Committee notes that it is unclear from the Exposure

Draft whether the $6,000 threshold for the purposes of the fee cap applies to:

(a) the total value of a member’s interest in a fund; or, (b) the amount within

each MySuper product or choice product. On one reading, it would be possible,

for example, for a member to have $5,000 in six different choice products

(representing a total balance of $30,000) and still have the amount of their

fees capped. This would not appear to be the policy intent but arises from the

wording of proposed s 99G ... If each investment option is a separate product (as

seems to be the schema of the section) then the fee cap applies for every

investment option that has less than $6,000 invested in it.[70]

Similarly, Mercer Consulting Australia submitted that it

is appropriate for the fee cap to apply at the product level, but given the

uncertainty of the wording contained in proposed subsections 99G(1), (2)

and (5), application of the fee cap at the product level ‘would result

in much more complex administration requirements and inappropriate outcomes’.[71]

To this end, both the Association of Superannuation Funds

Australia (ASFA) and Mercer argued that the total account be regarded as a

single interest rather than each product.[72]

Fee cap

rate

Consumer advocate group CHOICE supports the fee cap but

questioned why it is set at three per cent when, ‘according to Rice Warner, on

average superannuation fees are close to 1%’.[73]

CHOICE welcomed the ability of the SIS Regulations to set the fee cap at a

lower rate and recommended that the ‘cap be reviewed as part of a broader

review of the legislation within four years’.[74]

Financial Counselling Australia considered that if the fee

cap is proven to be effective then it could be increased to include member

balances up to $10,000.[75]

The LCA submitted that it was not clear whether the MySuper

requirements in the SIS Act permitted trustees to vary down the fee cap

for certain classes of members with balances less than $6,000, submitting:

The Exposure Draft makes it clear that a fund will not breach

the MySuper fee charging rules to the extent that some MySuper members pay

different fees as a result of their fees being subject to the cap. However, it

is unclear whether fees must otherwise be calculated in the same way for all

members (subject to the cap) or whether it will be permissible for there to be

an altogether different regime for members with low account balances that would

be subject to the cap. For example, say that a fund charges a standard fee

of $180 per annum. For a member with a $6,000 cap, this equates to 3 per cent.

Is it the case that, for all members with account balances less than $6,000,

those remaining members must be charged precisely 3 per cent or would it be

possible to charge those members a lower fee of, say, only 2 per cent?[76]

(Emphasis added).

Mercer raised similar concerns, noting that a fund may

wish to waive certain fees for low balance accounts in order to avoid the

administrative complexity of applying elements of the fee. However, Mercer

considered that the proposed amendment to section 29TC of the SIS Act by

item 2 of Schedule 1 to the Bill did not necessarily permit such

a variation, and as such Mercer recommended that it should be amended to permit

variation from the standard fees ‘to the extent ... considered necessary or

expedient by the trustee ...to comply with section 99G’.[77]

Commencement

Some stakeholders consider that there is insufficient time

to comply with the measure before its commencement.[78]

Mercer considered that 1 July 2020 is a more realistic commencement date.[79]

Key

provisions—ban on exit fees

Item 15 of Part 1 of Schedule 1 to

the Bill inserts proposed section 99BA into the SIS Act to

prevent a regulated superannuation fund or an approved deposit fund from

charging exit fees except as prescribed by the SIS Regulations.[80]

An exit fee is defined under proposed

subsection 99BA(2) as ‘a fee, other than a buy-sell spread,[81]

that relates to the disposal of all or part of a member’s interests in a

superannuation entity.’[82]

According to the Explanatory Memorandum ‘this could include a deferred entry

fee or a percentage based fee. It is not related to the cost of disposing the

interest, rather it is a fee triggered by the disposal’.[83]

Similar to exit fees, buy-sell spreads must

be charged on a cost recovery basis and are permitted to be charged by a

regulated superannuation fund that offers a MySuper product.[84]

Items 1, 3–8, 12, 16 and 17

in Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Bill make a number of

consequential amendments to the SIS Act to update or remove references

to exit fee.

Stakeholder

comments—ban on exit fees

Opaque

nature of cost and fees

While stakeholders have generally welcomed the

Government’s objective of preventing the erosion of member balances, a number

of stakeholders are concerned that the measure, without appropriate safeguards,

will lead to fees and costs being passed on in other ways. For example, while

ISA, strongly supports the measure, it considers that there are ‘significant

gaps and inconsistencies in how funds report data on fees and costs’, such that

costs may be transferred elsewhere.[85]

Some stakeholder’s are of the view that the proposed ban on

exit fees could be undermined by the exclusion of buy-sell spreads from the

definition. For example, while CHOICE supports the ban on exit fees which it

considers is ‘a barrier to switching and competition’,[86]

it submitted:

... under the proposal funds are free to charge for buy/sell

spreads. These fees accrue when a fund buys into or sells an investment option,

so will still be incurred when switching to another fund. Despite buy-sell

spreads being disclosed alongside exit fees in product disclosures and a

requirement that they be cost reflective, these fees are extremely opaque. Often

the exact buy/sell spread is not known and therefore not disclosed in a product

disclosure statement; a person is instead left with a percentage-based range

they may be charged on exit.[87]

(Emphasis added).

Cbus echoed these concerns around the lack of transparency

around buy-sell spreads, recommending that the ban must also extend to buy-sell

spreads:[88]

... failing to tackle buy/sell spreads will result in the exit

fee being able to be gamed by funds imposing buy/sell spreads as a disincentive

for members to exit ... Cbus does not apply buy/sell spreads.[89]

COTA Australia also welcomed the ban on exit fees but

considered that a ‘switching fee’ may still be imposed under the SIS Act where

a member moves all or part of their balance within the same superannuation

fund.[90]

In response to stakeholder concerns regarding the ban on

fees resulting in funds redistributing fees to other costs such as buy-sell

spreads, the RIS states:

No change was made in response to these concerns, as trustees

are required to charge buy-sell spreads on MySuper and choice products on a

cost recovery basis and APRA’s ongoing reporting and monitoring would allow any

changes of this nature to be identified over time should they arise.[91]

CHOICE considers that a solution would be to provide the

regulator with the power to monitor fee levels, and give it power to act via

the regulations where unintended consequences are discovered.[92]

Conversely, the LCA submitted that there are some external

costs incurred by funds which, although banned under the proposed arrangements,

would nevertheless have to be priced in elsewhere by trustees:

... under the current law, exit fees can only be charged on a

cost recovery basis. So the actual costs incurred (and which are currently

passed onto members) will need to be paid for by other means. It will not necessarily

reduce the costs incurred by trustees through services provided by outsourced

administrators. Because the definition of ‘administration fee’ in s 29V(2)

includes ‘costs incurred by the trustee’, fees for processing benefit

payments charged by administrators will need to be absorbed within the general

administration costs charged to all members.[93]

(Emphasis added)

Multiple

withdrawals

Some stakeholders also expressed concerns around the

effect of multiple withdrawals by members. For example, Rest considered that

while a first withdrawal should be free, subsequent withdrawals should be

subject to cost recovery fees to ‘ensure that fund members ... are not

disadvantaged by the activities and strategies of individual members’.[94]

While ASFA supports the ban on exit fees, it considered

that this should not extend to partial withdrawals which ‘will increase costs

for the broader membership and do nothing to reduce the number of duplicate

accounts’.[95]

AFA considered that the exit fees should be limited to the

actual cost of imposing the withdrawal.[96]

Schedule 2—Insurance

for superannuation members

Background

The connection between insurance and superannuation began

in the 1950s with life insurance companies beginning to offer superannuation

products (primarily to the public sector and to male professionals in large

companies). Following the introduction of compulsory superannuation in 1992,

insurance continued to be provided in most default products.[97]

Legislative requirements to offer insurance were

introduced in the 2005 Choice of Fund reforms which specified that default

funds must provide a minimal level of life insurance cover (but not total and

permanent disability or income protection insurance). Funds did not necessarily

have to give members the choice to opt out.[98]

In 2012, the Australian Government made it mandatory for

funds to provide life and total and permanent disability insurance, on an

opt-out basis, in all MySuper products.[99]

Part 6 of the SIS Act contains provisions relating

to the governing rules of superannuation entities. In particular, section 52 of

SIS Act includes a range of covenants that must be included in, or are

otherwise taken to be included in the governing rules of a registrable

superannuation entity including:[100]

- to

formulate, review regularly and give effect to an insurance strategy for the

benefit of beneficiaries of the entity that addresses the type and level of

insurance offered having regard to the demographic composition of the

beneficiaries

- to

consider the cost to all beneficiaries of offering or acquiring insurance

- to

only offer or acquire insurance if the cost of the insurance does not

inappropriately erode the retirement income of beneficiaries and

- to

pursue insurance claims with reasonable prospects of success.[101]

In relation to MySuper products, a regulated

superannuation fund must ensure that the fund provides a permanent incapacity

benefit and a death benefit in the form of insurance to each MySuper member of

the fund—that is, TPD and life insurance.[102]

While most members can opt-out of either TPD or life insurance, the fund may

require that the member opt-out of both if they elect to opt-out of either.[103]

However, funds are not required to allow MySuper product members to opt-out of

TPD or life insurance if the trustee is satisfied that the risk to be insured cannot

be insured at a reasonable cost, or be provided on an opt-out basis.[104]

The Insurance Operating Standards contained in the SIS

Regulations also provide that a fund must not provide an insured benefit to a

member other than for death, terminal medical condition, permanent incapacity

and temporary incapacity for new members from 1 July 2014.[105]

Insurance

in Superannuation Voluntary Code of Practice

The announcement of the ‘Protecting Your Super Package’

followed the development of the Insurance

in Superannuation Voluntary Code of Practice (the Code) which is owned

by ASFA, AIST and the Financial Services Council (FSC).[106]

In November 2016, the Insurance in Superannuation Industry Working Group (ISWG)

was established to develop the Code, which was finalised in December 2017 and

came into effect on 1 July 2018.[107]

Funds adopting the Code have until 31 December 2018 to publish a

transition plan and must comply with the Code no later than 30 June 2021.[108]

The Code partly addresses some of the issues that the Bill seeks to remedy. However

the Code is not mandatory and failure to adhere to it is not subject to

statutory regulation.[109]

Inquiry

into the life insurance industry

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and

Financial Services (PJCCFS) reported on its Inquiry into the life insurance industry

in March 2018.[110]

Among other things, the terms of reference for the PJCCFS Inquiry included the

requirement to assess the benefits and risks to consumers of group insurance.[111]

Chapter 7 of the PJCCFS final report considers many of the issues that the Bill

seeks to address.[112]

The PJCCFS acknowledged that duplicate life insurance is a

‘substantial drain on superannuation balances with significant adverse

consequences for retirement incomes, particularly for those with low super

balances and/or not engaged with their accounts’.[113]

The PJCCFS considered that trustees’ failure to act to

remedy duplicate life insurance was ‘completely unacceptable given that systems

already exist which can be used to remedy the matter.’[114]

In this regard, the PJCCFS was of the view that the ATO’s SuperMatch system

provides trustees with an appropriate avenue to assist members to resolve

account and insurance duplication.[115] The Committee made a number of

recommendations, including:

- requiring

funds to inform members annually where their account is subject to erosion

because of the above factors, or ‘trigger points’ are reached, for example a

low balance

- requiring

the ATO to provide members with a Statement of Superannuation and Insurance

(based on data provided by trustees) when a taxpayer’s notice of assessment is

sent out

- requesting

the life insurance industry to undertake a prominent media advertising campaign

- the

Government should undertake a review of superannuation trustees to determine

their compliance with the covenants in the SIS Act

- the

Government should consider legislating to protect the retirement savings of low

balance accounts holders and members who do not receive any value from

insurance and

- the

Government should consider legislating to require life insurers to provide

regular updates to members regarding their policies.[116]

Productivity

Commission

With respect to insurance policies offered by

superannuation funds, the PC Draft Report found:

The deduction of insurance premiums can have a material

impact on member balances at retirement. This balance erosion is highly

regressive in its impact — it is more costly to members with low incomes.

It also has a larger impact on members with intermittent attachment to the

labour force, and those with multiple superannuation accounts with insurance

(the latter comprise about 17 per cent of members). Balance erosion for

low-income members due to insurance could reach a projected 14 per cent of

retirement balances in many cases, and in extreme cases (for low-income

members with intermittent work patterns and with multiple income protection

policies) could be well over a quarter of a member’s retirement balance.[117]

(Emphasis added).

The PC also found that ‘default insurance in

superannuation offers good value for many, but not for all, members’.[118]

Insurance can be little or no value where the policy is ill-suited to the

members’ needs, or the member is unable to claim against it—for example, in the

case of income protection policies where the member is not working or where the

member has multiple policies.[119]

According to the PC ‘younger members and those with intermittent labour force

attachment ... are more likely to have policies of low or no value to them’.[120]

The PC made a number of draft recommendations with respect

to insurance including:

- insurance

through superannuation should only be provided to members under the age of 25

on an opt-in basis (draft recommendation 14)

- ceasing

insurance on accounts where no contributions have been obtained for the past 13

months, unless directed otherwise by the member (draft recommendation 15)

- adoption

of the Code should be a mandatory requirement of funds to obtain or retain

MySuper authorisation (draft recommendation 17) and

- the

Government should commission a formal independent review of insurance in

superannuation which includes an examination of the costs and benefits of

retaining current insurance arrangements on an opt-out basis.[121]

Review of

default insurance in superannuation

KPMG’s report Review

of Default Group Insurance in Superannuation was prepared in September

2017 at the request of the ISWG to ‘undertake analysis into the costs and

benefits of default insurance in superannuation’[122]

and ‘to evaluate whether such ‘insurance may be unduly eroding retirement

savings’.[123]

Broadly, group insurance is a single policy which insures

a number of individuals who opt-in to the group, without the need for each

individual to obtain a separate policy from the insurer. This typically means

that individuals can be insured under a group policy without any, or otherwise

minimal risk assessment being made by the insurer. However, at certain points,

the insurer will generally review the collective risk of the group and

determine whether adjustments need to be made to the premiums. In the context

of superannuation, this means that a super fund can negotiate group insurance

policies with insurers for fund members. Members are subsequently insured

(currently under opt-out arrangements for MySuper) without the need for the

insurer to enter into individual contracts with the members and therefore

consider their individual characteristics. Under a group insurance model, the

collective risk of each individual is spread across the group rather than being

attributed to each individual. This can either increase or decrease the premium

you might otherwise pay under an individual policy depending on your risk

factors.

KPMG summarised the benefits of having group insurance in

superannuation as follows:

- Greater insurance coverage for a larger proportion of the

Australian population, thus helping to reduce Australia’s well documented

underinsurance issue.

- In some instances default insurance in super improves access to

insurance for people in high-risk occupations.

-

Higher levels of insurance benefits are paid through group

insurance compared to government safety net social security benefits, thus allowing

people to take better care of their family and dependants in the event of death

or disability.

-

80 percent of group insurance premiums are paid back to members

in claims, with 12 percent spent on expenses and commissions. By comparison, 50

perent [sic] of individual insurance premiums are paid back as benefits and 40

percent are spent on expenses and commissions.

-

There is lower cost and minimal need for underwriting in

comparison to individual insurance held outside superannuation.

- The income protection benefits offered under default insurance

disqualify recipients from claiming a full Disability Support Pension,

representing a significant saving to the public purse.

- Income Protection benefits save the government between $3 - $4.2

billion over 10 years in terms of claims on the Disability Support Pension.

- Tax on insurance payments benefit the public purse by $2.9

billion over 10 years, outweighing the costs of tax concessions provided to

group insurance in superannuation.[124]

The report also found that ‘females and younger members tend

to comprise a higher proportion of the low income earners’ and their

‘retirement savings are generally impacted to a greater extent than males,

older members and high income earners’.[125]

KPMG canvassed possible alternatives to reduce balance

erosion including:

- ensuring

default insurance takes into consideration the different needs of different

cohorts

- a

premium cap linked to a member’s superannuation guarantee payments could be

introduced to ensure that premiums are commensurate with a person’s salary

- cessation

rules may be applicable in the case of casual workers and those who are likely

to have interrupted or irregular work patters and

- querying

whether it was necessary to have both TPD and income protection as opposed to

one or the other depending on the cohort.[126]

Following the announcement of the ‘Protecting Your Super

Package’, KPMG also released Insurance

in Superannuation: The Impacts and Unintended Consequences of the Proposed

Federal Budget Changes. Appendix A to this Bills Digest sets out

some key findings from KPMG’s post budget analysis.

AIAA also commissioned Rice Warner to conduct research

into the proposed changes, Economic

Impact of 2018 Federal Budget Proposed Insurance Changes, which can be

found at Attachment two of AIAA’s submission to the Committee.[127]

Key

provisions—insurance

Item 1 of Schedule 2 inserts proposed

sections 68AAA–68AAE into Part 7 of the SIS Act.

Inactive

accounts

Under proposed section 68AAA of the SIS Act a

regulated superannuation fund must ensure that insurance is not taken out or

maintained by the fund for a member under a choice or MySuper product held by

the member if:

- the

member’s account is inactive in relation to that product for a

continuous period of 13 months and

- the

member has not made an election in writing to otherwise take out

or maintain the insurance under the choice or MySuper product.[128]

A member’s account is taken to be inactive in

relation to a choice or MySuper product if the fund has not received an amount

in respect of the member that relates to that product during that period.[129]

Once such an amount is received, the prohibition from providing insurance ceases

to apply until the account has been inactive for another 13 months.[130]

Proposed section 68AAA applies from 1 July 2019.[131]

However, the period before 1 July 2019 is taken into account when determining

if an account is inactive.[132]

This appears to indicate that the date from which inactivity is determined is

the last date on which the members account received an amount.

Low-balance

accounts

Under proposed section 68AAB of the SIS Act a

regulated superannuation fund must ensure that insurance is not taken out or

maintained by the fund for a member of the fund under a choice product or

MySuper product held by the member if:

- the

member has an account balance with the fund that relates to the product that is

less than $6,000

- on

or after 1 April 2019, the member has not had an account balance with the fund

that is $6,000 or more and

- the

member has not made an election in writing to otherwise take out or maintain

the insurance under the choice or MySuper product.[133]

If the member makes an election to otherwise take out insurance

notwithstanding an account balance of less than $6,000, the member is also

taken to have made an election under proposed subsection 68AAC(2)

(members under 25 years old) and vice-versa.[134]

Proposed section 68AAB applies from 1 July 2019.[135]

However, in order to ‘manage potential administrative and compliance burdens in

relation to superannuation balances that fluctuate around the $6,000 threshold

amount’,[136]

proposed section 68AAB only applies if the member’s balance does not

reach $6,000 at any time on or after 1 April 2019. This means that once a

member’s account balance reaches $6,000 on or after 1 July 2019, the proposed

amendments will not apply unless the member’s account subsequently becomes

inactive or where the member is under 25 years and began to hold the account on

or after 1 July 2019.[137]

Members

under 25 years of age

Under proposed section 68AAC of the SIS Act,

a regulated superannuation fund must ensure that insurance is not taken out or

maintained by the fund for a member under a choice product or MySuper product

held by the member if:

- the

member is under 25 years and

- the

member has not made an election in writing to otherwise take out or maintain

the insurance under the choice or MySuper product.[138]

As noted above, if the member makes an election to

otherwise take out insurance even if they are under 25 years old, the member is

also taken to have made an election under proposed subsection 68AAB(2)

(low-balance accounts) and vice-versa.[139]

Proposed section 68AAC applies from 1 July 2019 to

members who are under the age of 25 years and begin to hold the product on or

after 1 July 2019—that is, it does not apply to those who are under 25 years

and already hold such a product.[140]

The LCA noted that from a practical perspective perhaps a

grace period following a member’s 25th birthday is necessary, in which

insurance can be established for the member—otherwise the fund may be in breach

of the MySuper rules.[141]

Exceptions

Proposed sections 68AAA and 68AAB of the SIS

Act do not affect a member’s right to be covered by insurance until:

- the

end of the period for which the premiums have been deducted or

- the

expiry date of the term of the member’s existing insurance cover.[142]

The prohibition on providing opt-out insurance under proposed

sections 68AAA, 68AAB and 68AAC of the SIS Act is not

universal. It does not apply to:

- regulated

superannuation funds with fewer than five members[143]

- a

defined benefit member[144]

- a

member that is or would be an ADF Super member[145]

or

- a

member to whom the employer-sponsor contribution exception

applies.[146]

The employer-sponsor contribution exception applies

where a member’s employer makes contributions in addition to the superannuation

guarantee which is equal to or greater than the insurance fees relating to

insurance benefit for each quarter.[147]

The quarter is a period of three months beginning on 1 January, 1

April, 1 July or 1 October.[148]

Item 2 in Part 1 of Schedule 2 to the Bill

‘turns off’ a fund’s legislative requirement to provide TPD and life insurance,

if such insurance is not permitted under proposed subsections 68AAA,

68AAB or 68AAC.[149]

Notification

requirements prior to commencement

Part 2 of Schedule 2 to the Bill contains

provisions for the application, transitional and fund notification requirements

required to give effect to the proposed changes. Item 6 in Part 2

of Schedule 2 to the Bill provides that ASIC rather than APRA has the

general administration of the amendments inserted by items 3 and 4

of Schedule 2 to the Bill—that is, inactive accounts and low-balance

accounts.

Inactive

accounts

Subitem 3(3) in Part 2 of Schedule 2 to the

Bill requires regulated superannuation funds to ensure that on 1 April 2019

account balances that have been inactive for the previous six months are

identified, and on or before 1 May 2019 each member associated with such

accounts is given written notice specifying:

- insurance

will not be provided from 1 July 2019 if the account is inactive for 13 months

and

- the

member can by written notice elect to take out or maintain that insurance.[150]

If, after 8 May 2018 but before 1 July 2019, the member

gives the fund written notice by taking out or maintaining insurance in

relation to the product, the fund is not required to provide notice to the

member under subitem 3(4) in Part 2 of Schedule 2 to the Bill.

Low-balance

accounts

Similarly, subitem 4(2) in Part 2 of Schedule

2 to the Bill, requires superannuation funds to ensure that on 1 April 2019

they identify members with insurance products whose account balances are less

than $6,000, and on or before 1 May 2019 each member associated with such

accounts is given written notice specifying:

- that

from 1 July 2019, the fund will not provide the member with insurance if they

have not had an account balance of $6,000 or more on or after 1 April 2019 and

- the

member can by written notice elect to take out or maintain that insurance.[151]

Notice does not need to be given by the fund, if before 1

April 2019 the member gives the fund notice by taking out or maintaining

insurance in relation to the product.[152]

In contrast to the notice requirement under subitem 3(6) of Schedule

2 to the Bill, written notice is not required. The Explanatory

Memorandum states:

While the amendments do not require a member to have made the

election in writing, if insurance is provided by the trustee on an opt out

basis after 1 July 2019, and the member has not asked for it to be provided,

the trustee may be in breach of the RSE licensee law. A trustee will need to be

able to demonstrate that a member has elected to maintain cover, other than in

writing by, for example, a record of a meeting or a note following a telephone

conversation.[153]

If a member begins to hold a product under which insurance

may be provided after 1 April 2019 but before 1 July 2019, the fund must

provide the member with written notice stating that the fund will not provide

the member with insurance from 1 July 2019 if the member has an account balance

of less than $6,000 and, on or after 1 April 2019, the member has not had an

account balance of $6,000 or more and the member has not elected to take out or

maintain insurance notwithstanding a low balance account.[154]

Stakeholder comments

Stakeholder views vary on the scope and application of Schedule

2 to the Bill.

ISA welcomed the ‘good intention of protecting members’

superannuation balances’, but considered that the measure was too broad,

stating:

Poorly targeted changes will result in more than 3.7 million

Australians being excluded from default insurance, many of whom have a

particular need for insurance. These reasons include having a mortgage, working

in a high-risk occupation, or supporting dependants.

Importantly the consolidation of multiple accounts through

the measures set out in Schedule 3 of the Bill will, by definition, address

most instances of duplicate insurance cover in superannuation. Therefore, on

this matter the need for separate measures to address duplicate insurance cover

is significantly diminished.[155]

Similarly, MetLife Insurance Limited (MetLife) supports

the changes that would have occurred as a result of the Insurance in

Superannuation Working Group, but considers that the current proposed changes

go much further. Of particular concern is that the amendments may operate to

increase ‘administrative costs and premiums for remaining members in the group

insurance system, potentially leading to greater erosion of their retirement

savings’.[156]

Conversely, ClearView Wealth Management (ClearView) supports

the changes but considers that they should only be considered to be ‘a first,

but important, step towards a scenario in which life insurance in super becomes

optional on an opt-out basis for all workers’.[157]

In this respect ClearView argues that there are various shortcomings with group

insurance including that the ‘one-size-fits-all approach means the standard

amount of cover is usually very limited, there is a lack of member education or

advice, members pay for products that they do not or cannot use, the healthy

subsidise the unhealthy and the reduced costs of group insurance are only

‘illusory’.[158]

While Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand

(CAANZ) considered that the current model has led to some cases of fund members

paying for insurance that they neither need nor want, it was of the view that

allowing a member to opt-in changes the ‘contract dynamics and therefore the

pricing that insurers are willing to offer’. To this end CAANZ submitted that

the Government has insufficient data to model the medium and longer term impacts

and suggested further research be undertaken by an expert.[159]

AIAA ultimately recommended that an opt-out model should

be maintained for low-balance accounts and under 25 year olds. Furthermore, it

considered that changes could be better effected though the Code which should

be made mandatory.[160]

TAL submitted that the proposed changes fail to take

account of a member’s previous election with respect to insurance. TAL

recommended that those members who have previously applied for, changed or

preserved their insurance cover should be excluded from the measure.[161]

Members

under 25 years of age

While AIAA broadly supports the opt-in insurance

arrangements for inactive accounts, it submitted that the Government has not

adequately considered the unintended consequences of removing opt-out insurance

for under 25 year olds and low-balance accounts.[162]

AIAA submitted the following rationale for group insurance:

The system works by distributing risk across a pool of known

members to form a ‘community rating’ within a fund, allowing for lower

premiums, limited or no underwriting, broader coverage and fewer administration

fees. This collective response to risk benefits all Australians and can only be

achieved on an opt-out basis ... By design, it provides cover to exactly those

individuals who would either not opt in to or be unable to attain insurance

cover at all, or on reasonable terms.[163]

With respect to the removal of opt-out insurance for under

25 year olds, AIAA contends that it is an ‘ill-conceived’ notion that young Australian’s

do not need the protections of life insurance, stating:

- AIAA paid $84 million on 1200 claims for people under 25 since

2015. This grows year on year.

-

Rates of IP and TPD claims at AIAA are approximately the same for

people aged 20 and those aged 30. This is also reflected industry-wide.

-

Mental illness is the largest claim cause at AIAA for permanent

disability for members up to 25.[164]

AIAA also considered that under an opt-in model, those

aged under 25 year will be significantly underinsured because of an apathy

towards superannuation generally and the ‘misguided belief’ that they are

unlikely to be the subject of a life insurance event.[165]

AIAA estimates that less than ten per cent (possibly as low as two per cent) of

young people are likely to opt-in under the Government model.[166]

TAL agrees that the young people had different insurance

needs to other superannuation members who in comparison are less likely to have

dependants and liabilities.[167]

However, TAL considers that this is not the case for all young members.

Accordingly, TAL recommends that individual trustees be given the discretion to

determine the appropriate minimum age for opt-in insurance between the ages of

21 and 25 years.[168]

ISA took a similar view stating that ‘empirical data reveals insurance needs

crystallise in the early rather than mid 20s for most’, and from the age of 22,

workers are ‘significantly more likely to have insurance needs’.[169]

ISA submitted that the prescribed age at which opt-in insurance can apply

should be lowered to 22 years old.[170]

This appears to be consistent with the Australian Government Actuary’s advice

to Treasury which stated that ‘funds have very different allocations of members

under age 25’.[171]

The Grattan Institute considered that it is not clear why

it is desirable for members who are young, have inactive accounts or have small

balances, to cross-subsidise other members as a result of opt‑out group

insurance.[172]

Mr Allan Hansell, Director of Policy and Global Markets at FSC submitted the

following justification:

People talk a lot about cross-subsidisation between the

various age cohorts. But if you look at a person, they will commence in an

insurance scheme as a younger member, and, yes, there will be a level of

cross-subsidisation that occurs between them and older people, and the sick;

but then, as they move through the life cycle, they end up getting the same

level of support from younger members at a future date, because they remain as

a member of the scheme. The whole concept of pooling is cross-subsidisation.

Members put money into the insurance pool to cover off their risks, and when

their health is compromised or they suffer from an illness, they draw down on

the risk pool. If someone's healthy, then that's great, but they've got

that insurance cover in place and they pay the premium for it.[173]

(Emphasis Added).

Low balance

accounts

AIAA contended that notwithstanding that an account may be

a low-balance account, those account holders are still making insurance

contributions and accordingly have ‘insurance needs’.[174]

Of particular concern to AIAA is the period of time a member will remain

uninsured until their account balance reaches $6,000:

For an average full-time working Australian with total

earnings of $81,500, it would take 11 months to accumulate sufficient

contributions in a new account to meet the $6,000 threshold. For the average

working Australian with total earnings of just under $62,000, it would take

almost 15 months to accumulate this amount.[175]

Maurice Blackburn Lawyers expressed similar concerns, noting

that a low-balance account shouldn’t be a determining factor in whether a

member requires TPD and death insurance or not.[176]

AIAA also contended that the policy fails to consider the rise of mental health

related claims, stating:

Mental ill health has grown to now represent the third

largest area of all claims at AIAA, sitting behind only cancer and

musculoskeletal conditions as the leading claim causes. Mental ill health is

also the largest claim cause at AIAA for group insurance TPD claims for members

under 25, representing one in four of all claims; and is the third largest

claim cause for IP.[177]

TAL submitted that only inactive members with account

balances below $6,000 should be removed from opt-out insurance arrangements.[178]

TAL estimates that in the ‘financial year ended 30 June 2017, $560m was paid to

members in life and disability claims with superannuation account balances less

than $6,000’.[179]

Accordingly, TAL considers that if an account is receiving contributions, the

member should be provided with insurance cover.[180]

Inactive

accounts

ISA and other stakeholders consider that the measure is

likely to significantly impact women, submitting:

The proposed measures put the economic security of thousands

of women and their children at risk. ISA analysis of Australian Bureau of

Statistics (ABS) data shows that the reforms will affect 1.8 million inactive

members, of whom 960,400 are women. Over 75 per cent of people impacted are

over the age of 35 and three quarters of them have at least one dependant. Over

a quarter of a million women between the ages of 35 and 44 will be declared

inactive; 90 percent of these women have dependants. Overall, 1.65 million

children will have at least one parent who is no longer eligible for default

insurance coverage.[181]

(Citations omitted).

The ACTU and MetLife expressed similar concerns.[182]

AIS submitted that members who need to opt-in to insurance

arrangements as opposed to collective risk pooling, ‘will be subjected to

underwriting, including health checks, and additional cost’.[183]

Treasury notes that 13 months was considered to be a

reasonable time and consistent with the period adopted by the ISWG.[184]

High risk

occupations

Several stakeholders expressed concerns that it may be

difficult for individuals to obtain insurance where they are engaged in a high

risk occupation.[185]

For example, financial consultancy firm Rice Warner considered that

‘superannuation funds may be the only option to obtain insurance cover for

individuals working in a range of high risk occupations.’[186]

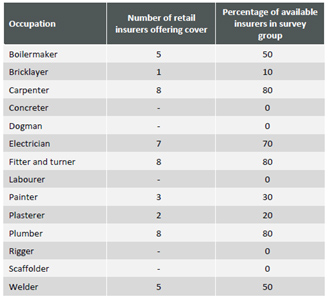

Table 2 shows Rice Warner’s own investigation of the availability of cover in

the retail market for some high risk occupations in the building industry.

Table 2: Retail insurance availability for high risk building and

construction occupations

Source: Rice Warner, Submission,

p. 4.

However, Professor Daley of the Grattan Institute

emphasised that work-related accidents would be covered by workers’

compensation which ‘will be substantially more generous than anything available

under default insurance’,[187]

and therefore default insurance effectively double insured a member:

For example, if a worker died through a work related accident

in Victoria, the total compensation that would go to their dependants, or at

least their partner as a dependant, is in the order of about $730,000, and then

there will be additional money for children. In New South Wales, it is about

$791,000. It is worth comparing that to the average benefit through

superannuation, which is only about $100,000, and even the high-end benefits ...

are only about $400,000.[188]

Accordingly, Professor Daley encouraged funds and insurers

to develop policies that covered members for non-work related accidents.[189]

Impact on

the economy and retirement balances

In advice to Treasury, the Australian Government Actuary

advised that ‘... it is important to recognise that the proposed changes to

insurance eligibility will have a major impact on the superannuation industry

and individual members’.[190]

The Australian Government Actuary estimates that there will be a premium

revenue loss in the industry of less than 50 per cent, which will

represent a ‘significant reduction in premium revenue, possibly in the order of

$1b to $1.5b’.[191]

Rice Warner estimates, based on its analysis of its Super

Insight’s database, that ‘around 40%-50% of the total sum insured would be

lost under the full suite of changes to insurance opt-in arrangements’.[192]

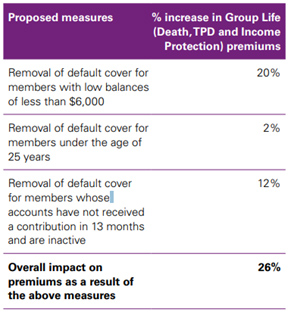

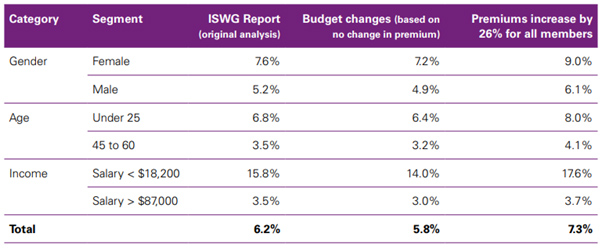

Different submissions have estimated the overall premium

increases that will result from the measure depending on the group

affected—that is members with low balances, those aged less than 25 years and

those members with inactive accounts.[193]

The Australian Government Actuary estimated that premiums could rise in the

order of:

- under

25 and less than $6,000—90 per cent

- under

25 and greater than $6,000—five per cent

- accounts

held by over 25s after impact of cessation and opt-in for those with less than

$6,000 and inactive accounts—seven per cent to ten per cent.[194]

Rice Warner acknowledged that ‘for most individuals who do

not make a claim over their working life, removal of default life insurance