Budget Review 2021–22 Index

Ian Zhou

What is a patent

box?

A patent box is a tax regime that provides a lower tax rate for

some kinds of income derived from certain forms of intellectual property (IP)—typically patents but sometimes other forms of IP such as

designs and copyright material. The policy goal of patent

boxes is to promote research and development (R&D) and the

commercialisation of IP.

According to a United

States Congressional Research Service article, patent boxes get their name

from the box on an income tax form that companies check if they have qualified

IP income (p. 2). A patent box may also be viewed as a metaphorical box: patents meeting stated criteria—that is, patents

that are ‘in the box’—attract concessional tax treatment for the income they generate.

What is proposed

in the Budget?

In the 2021–22 Budget, the Government announced

it will establish a patent box tax regime in Australia for certain income

generated from Australian medical and biotechnology patents (Budget Measures: Budget Paper No. 2: 2021–22, p. 23). As part of the measure, the Government will

consult with industry to determine whether a patent box is also an

effective way of supporting the clean energy sector.

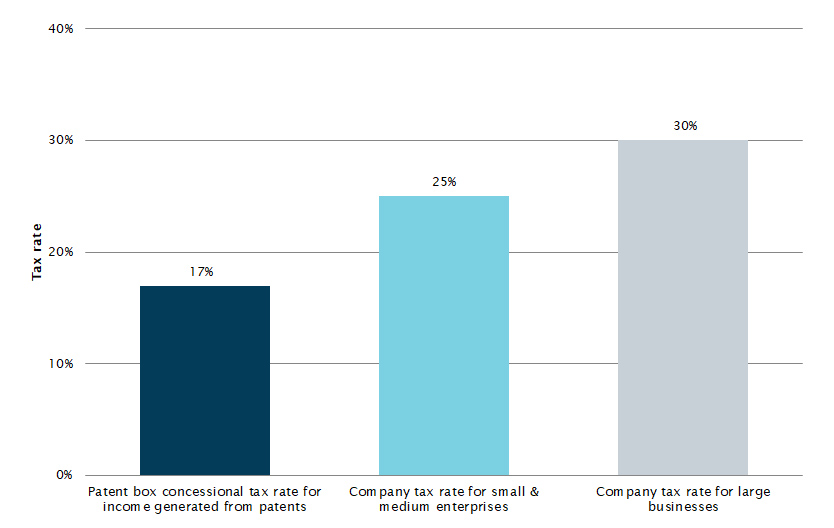

The patent box tax regime will provide a

17% concessional tax rate for corporate income derived directly from medical

and biotechnology patents. The usual corporate income tax

(CIT) rate is 30% for large businesses and 25% for small and medium enterprises

(for the 2021–22 income year onwards).

The proposed tax regime will commence on 1

July 2022, subject to legislation. The tax concession will apply to

patents granted after the budget announcement on 11 May 2021, with the

concessional tax rate to apply in proportion to the percentage of the patents’ underlying

R&D activities conducted in Australia.

According to the 2021–22

Budget’s tax factsheet,

the patent box ‘encourages businesses to undertake their R&D in Australia

and keep patents here’.

This measure will require legislation.

Figure 1: patent box’s concessional tax rate compared to corporate income

tax rate from 2021–22

Source:

Parliamentary Library estimates based on Australian Government, Budget Measures: Budget Paper No. 2: 2021–22, p. 23; Australian Taxation Office (ATO), ‘Changes to company tax rates’, ATO website, last modified 30 November

2020.

Who will benefit from Australia’s

patent box?

The proposal

has the potential to benefit the medical and biotechnology

sector, which includes pharmaceutical companies. It will be larger

companies that derive the most benefit because large multinational enterprises

(MNEs) tend to apply for and own more patents than local small and medium

enterprises (SMEs). For example,

UK government statistics shows that in 2016–17,

more than 95% of the tax relief claimed under the UK’s patent box regime came

from large companies rather than SMEs (pp. 2, 8).

Which income is

concessionally taxed?

The patent box tax concession will apply only

to income generated directly from patents, typically royalty

income or capital gains that arise from the licencing or sale of patents.

Income derived from manufacturing, branding, or other attributes

will be subject to the existing CIT rate at 30% or 25%, depending on the size

of the company. For example, if an overseas firm owns a patent and an

Australian manufacturer is licenced to produce goods based on the patent, the

Australian manufacturer would be unable to claim the 17% concessional CIT rate

because its income is not directly generated from the patent.

The concessional tax rate provided by the patent box could

potentially give rise to MNE tax avoidance behaviours. This issue is addressed

further below.

Where will the R&D activities

be required to take place?

The 2021–22

Budget’s tax factsheet indicates that companies will be eligible to benefit

from the patent box tax concession only if the R&D activities underpinning

the relevant patents are undertaken in Australia.

For example, if a company makes $100.0 million in net income

that is derived directly from its patent, and the company conducted 80% of the

patent’s research in Australia, then only $80.0 million income will be taxed at

the 17% concessional rate. The remaining $20.0 million income will still be

taxed at the 30% company tax rate.

Implementing the policy may present difficulties for the ATO

to accurately attribute a company’s ‘qualifying R&D expenditure’ to a

specific patent and income from that patent.

Why is the

Government introducing a patent box?

R&D activities are widely perceived to have positive benefits

(known as ‘externalities’) that spill-over to other parts of the economy and

benefit the rest of society. As such, some governments attempt to promote

R&D activities through a combination of direct investment and tax

incentives.

Currently, over

20 countries have some form of patent or IP box tax regime (p. 3). While patent

box tax regimes can differ widely in their scope, they are mostly designed to

achieve some or all of the following objectives:

- promote increased investment in R&D activities

- promote the commercialisation of research and

- prevent the erosion of the domestic tax base that can occur when

mobile sources of income are transferred to other countries.

The assumption underlying all three objectives is that IP is

highly mobile and companies that own IP can relocate these assets to

jurisdictions that provide favourable tax treatment.

Governments around the world have increasingly sought to

modify their tax regimes to incentivise the retention and acquisition of IP. This

competition between countries has resulted in ever more generous tax regimes

that enable large MNEs to access low tax rates for IP related income without contributing

significant amounts of R&D expenditures in the host country. The OECD

considers this type of competition to be a harmful tax practice (p. 14). In

other words, patent box tax regimes can potentially give rise to harmful tax

practices or lead to ‘a race to the bottom’ if they are designed or implemented

poorly.

For example, MNEs can file patent applications in low-tax

jurisdictions while undertaking manufacturing of the patented product in

another jurisdiction, even if their headquarters may be located in yet another jurisdiction.

This is particularly attractive where the patents have a high earnings

potential.

Furthermore, large MNEs are likely to possess the tax

planning expertise to relocate mobile sources of income such as IP income to

low-tax jurisdictions through transfer pricing or licensing agreements, including

with their subsidiaries. These types of corporate behaviours can potentially erode

the host country’s tax base and reduce the number of patents filed in ‘high

tax’ jurisdictions (p. 41).

OECD recommendations

The OECD/G20

BEPS (base erosion and profit shifting) project provides 15 Actions that

equip governments with the domestic and international instruments needed to

tackle tax avoidance behaviours.

BEPS

Action 5 recommends countries adopt the ‘modified

nexus approach’ for patent box tax regimes to ensure that patent boxes do

not give rise to harmful tax practices. BEPS Action 5 is endorsed

by all OECD and G20 countries (including Australia). The Australian Government

also said

it will follow the OECD’s guidelines to ensure the patent box meets

internationally accepted standards (p. 3).

The ‘modified nexus approach’ aims to ensure that the tax

benefits received by MNEs are commensurate with the level of R&D they

undertake.

What are the pros and cons of

patent boxes?

The debate around the benefits of patent boxes is highly

contested, with no consensus view emerging as to their overall effectiveness. The

following three questions are central to the debate on patent boxes:

- Do patent boxes promote economic growth and innovation?

- Do potential benefits of patent boxes outweigh their drawbacks?

- Are there better alternative policy tools to promote innovation?

In 2015, the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science

published a report titled, Patent

Box Policies. The report found that a patent box regime should lead to

an increase in the number of patent applications. However, this increase would

largely be the result of ‘opportunistic’ behaviour and would not reflect a

genuine increase in inventiveness (pp. 24–25). As such, the report concluded

that:

patent boxes are not a very

appropriate innovation policy tool because

they target the back end of the innovation process, where market failures are

less likely to occur. [emphasis added] (p. 24)

The conclusions reached by the 2015 report have been disputed

by industry stakeholders.

In 2016, the Joint

Select Committee on Trade and Investment Growth’s Inquiry into Australia’s Future in Research and

Innovation also cautioned that:

If a patent box is introduced, it should be subject to a

sunset clause after three years of operation. A review should be undertaken to

determine the effectiveness of the patent box scheme and whether it should be extended

and for how long. (p. xv)

Advocates

of patent boxes (e.g. medical companies and some industry stakeholders) argue

that the tax regime will promote the commercialisation of research in Australia.

They believe this is one of the key differences between patent boxes and

R&D tax incentives (pp. 2, 10).

Many countries (including Australia) have already introduced

R&D

tax incentives as a policy tool to encourage innovation. Australia’s

current R&D tax incentive program is ‘input‐based’—that is, the program

encourages companies to invest in eligible

R&D activities, and in return the companies receive a tax benefit

regardless of whether they ultimately commercialise their research.

Patent box tax regimes are ‘output‐based’ measures

that provide tax concession for corporate income generated from patents already

filed and registered—that is, after the R&D has occurred. If a patent is

not commercialised and generates no income, then the patent owner is unable to

claim the patent box’s concessional tax rate.

When a company develops a patent in Australia, it can choose

to commercialise the patent by licencing the use of the patent to Australian or

overseas manufacturers. The patent box regime is intended to incentivise the company

to commercialise the patent onshore in Australia by providing a concessional

CIT rate for the corporate income generated from the patent.

CSL

Limited, a biotechnology company, stated:

CSL welcomes the introduction of a Patent Box which will help

decrease the flow of intellectual property from local medical research going

overseas. It will drive the growth of advanced manufacturing jobs, capital

intensive investment and sovereign capacity in medical technology and

biotechnology manufacturing.

Table 1 provides an overview of the potential benefits and

drawbacks of patent boxes put forward by stakeholders and academics.

Table 1: Potential benefits and

drawbacks of patent box regimes

|

Potential benefits of a patent box

|

Potential drawbacks of a patent box

|

|

Patent boxes

may incentivise firms to undertake more R&D activities as the cost of

doing so is reduced due to lower taxation (see Office of Chief economist,

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, ‘Patent

Box Policies’, pp. 9-10).

|

Due to the tax concession, patent boxes may lead to

a decrease in tax revenues collected from innovative firms (‘Patent Box Policies’, p. 10).

Furthermore, patent boxes may lead to a ‘the rich

getting richer’ situation because the tax concession could increase the

post-tax profits of large pharmaceutical companies that possess a large

number of patents (Institute for Fiscal Studies (UK), ‘Corporate

Taxes and Intellectual Property: Simulating the Effect of Patent Boxes’, p. 15).

|

|

By providing a

concessional tax treatment, patent boxes may encourage firms to patent

inventions that would have otherwise been kept secret (‘Patent

Box Policies’, p. 10).

|

Additional patent applications may be

‘opportunistic’ and not tied to real economic activity (‘Patent Box Policies’, p. 25).

Additional patent applications may also lead to a

‘patent gridlock’ situation, when miniscule aspects of a technology are

patented and new innovators lack the resources to access relevant patents to

start their research.

|

|

Increased

volume of patents will mean increased revenues for the patent office, as well

as greater disclosure of technical knowledge (‘Patent

Box Policies’, p. 11).

|

Increased patent volumes may not deliver purported

benefits where the patent office does not have the requisite resources to

process patents. Further, an inadequately resourced patent office may lead to

a backlog of applications, creating greater uncertainty and placing increased

pressures on start-ups who are looking to secure funding based on the patent

being processed (‘Patent Box Policies’, p.11).

|

|

Patents boxes

could encourage the commercialisation of research as the tax incentives are

‘output based’ (Institute of Public Accountants, ‘2020-21

Pre-Budget Submission’, p. 35).

|

Not

all R&D is patentable. As proposed, patent boxes provide tax concession

to patents only and this may discourage companies to engage in un‑patentable

research (Alstadsæter et al, ‘Patent boxes design, patents location, and local

R&D’, Economic Policy Journal, p. 138).

|

|

Depending on

the specific design of patent boxes, they could reduce the erosion of domestic

tax base by encouraging firms to commercialise R&D activity which has

occurred locally (Australian Medical Manufacturing Exporters Coalition, ‘2021-22

Pre-Budget Submission’, p. 10).

|

Depending on the design, patent boxes could

encourage multinational firms’ profit shifting activities (Tax Justice

Network, ‘Corporate Tax Haven Index 2019’, pp. 3–4). This is particularly pertinent given the

sensitivity of multinationals to patent box tax rates, and the difficulties

associated with accurately attributing revenue to a specific patent.

|