Chapter 1 - The significance of the Gallipoli

Peninsula

1.1 The Senate Inquiry into matters relating to the Gallipoli Peninsula was established on 11 May 2005 to investigate the role of the Australian Government in the construction and repair of roads on the Gallipoli Peninsula by Turkish authorities.

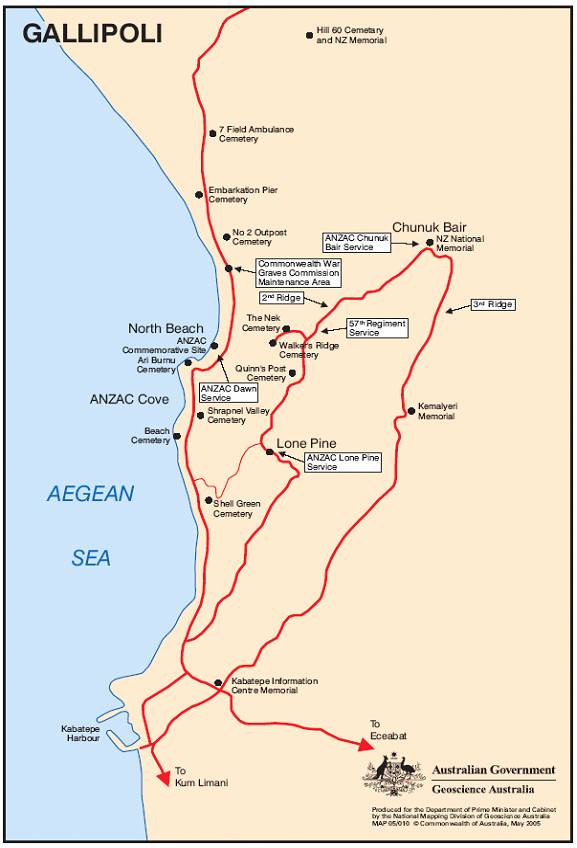

1.2 There are two roads in question—the coastal road past North Beach and ANZAC Cove, on which work has been largely completed, and the inland road from Chunuk Bair in the north to Lone Pine, on which there has not been recent work.[7]

1.3 The inquiry was initiated following evidence that the Australian Government had requested construction work on both these roads, and allegations in the media that construction on the coastal road had uncovered human remains, damaged the fragile environment, and destroyed sites of military heritage significance for the first landings and subsequent fighting at ANZAC Cove.

1.4 The Committee's terms of reference inquired into the Australian Government's request for roadworks to be undertaken, the involvement of Government ministers and officials in negotiating the roadworks with Turkish authorities, and the heritage protection of ANZAC Cove by way of planning and research.

1.5 This chapter sketches the historical significance of the Gallipoli Peninsula for both the Australian and Turkish people. It identifies the main changes that have occurred to the site since the end of World War I, and the legislative framework for the coordination of these efforts between the Turkish and Australian Governments.

The 1915 campaign

1.6 On 2 August 1914, two days before Turkey went to war with the Allies, Turkey and Germany signed an alliance that pitted both nations against Russia.[8] Turkey's alliance with Germany was fairly pragmatic. The Ottomans had no grievance with either France or Britain, but saw the Russians as a traditional enemy. Many within the Turkish bureaucracy, including the Minister of War, Enver Pasha, had sympathies with the Germans. After a flurry of diplomatic activity, it was that linkage which prevailed.

1.7 The 1915 Dardanelles campaign was intended as a means for the Allies to make progress on a second front, linking with Russia to the north, given the prospect of prolonged trench warfare on the Western Front. In September 1914, Winston Churchill's plan was clear: 'a good army of 50 000 men and seapower—that is the end of the Turkish menace'.[9] The plan was for the Allies to claim the Dardanelles, and then Constantinople (Istanbul).

1.8 By February 1915, however, the British command believed a swift and effective naval attack would be adequate. On 19 February, Allied battleships entered the Dardanelles and attacked the fixed guns on the outer Turkish forts.

1.9 The naval attack came to a head on 18 March, when seventeen Allied battleships attacked Turkish forts at the Narrows. In the ensuing battle, the Allies lost three of these ships—Ocean, Irresistible and Bouvet—and another three—Gaulois, Suffren and Inflexible—ran aground or were shelled. On 18 March, 700 British and French sailors were killed; the Turks lost 40 soldiers. It was in response to the complete failure of the naval campaign that the Allies questioned the merit of a military landing on the Peninsula. In the event, the decision was made to proceed with an army of 75 000 men, including ANZAC troops on training exercises in Egypt. The ANZACs had been preparing for conflict on the Western Front.

1.10 The 1915 conflict on the Gallipoli Peninsula was part of an Allied plan for Australian and New Zealand troops to distract the Turkish army from British troops landing further down the peninsula. It was hoped that the British would then face little resistance in their push to capture the Dardanelles, and then Istanbul, assuming naval success.

1.11 The Australian Imperial Force's 9th and 10th battalions landed at what is now ANZAC Cove, shortly before dawn on 25 April 1915, and made initial progress up steep slopes. By day's end, however, they were ordered to dig trenches, as Turkish forces had secured the cliffs. After six months of trench warfare, the British commanders realised the campaign's failure and ordered a withdrawal.[10]

1.12 The nine-month conflict on the Peninsula cost the lives of 87 000 Turkish, 22 000 British, 10 000 French, 8700 Australian and 2700 New Zealand soldiers, among others.[11] In total, around 450 000 people were killed or wounded.[12] It is estimated that one-third of Allied soldiers who fell have no known grave; the figure is much higher for the Turkish army.[13] It is estimated that 4200 Australians were never recovered.

The national and heritage significance of the Peninsula

1.13 The national significance of the 1915 conflict, and the heritage value of the Gallipoli Peninsula, is undisputed. Australia's greatest military defeat has been transformed, through time and remembrance, into iconic status.[14] The battle is widely regarded as the cornerstone of Australian military history, and by many Australians as the unofficial symbol of nationhood. It was reported first-hand by the revered military historian, Charles Bean; popularised in Peter Weir's 1981 film, Gallipoli; authoritatively documented in Les Carlyon's 2001 book of the same name; and recently depicted in Dr Peter Stanley's book, Quinn's Post.

1.14 The Turkish people similarly view the Canakkale naval and Gallipoli land battles as founding national events, albeit for different reasons. The conflict was Turkey's sole victory in five First World War campaigns.[15] It is seen as the last great victory of the Ottoman Empire. More particularly, it flagged the military capability and ambition of Mustafa Kemal, and the beginning of his role in Turkey's transition to a secular republic.

1.15 Kemal—who in 1923 became the first president of the newly-created Republic of Turkey—was commander of the 19th Division at Gallipoli. He was on hand to oppose the Allied landing in April 1915, and was feted for his military strategy.[16] In 1934, Kemal was awarded the title 'Ataturk'—father of the Turks. The same year, he wrote of the ANZAC's killed at Gallipoli, 'you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country'.

The Gallipoli Peninsula, the Peace Park & the ANZAC Commemorative site

1.16 A submission to the Committee from the Department of Veterans' Affairs asserted that the physical appearance of ANZAC Cove has changed significantly since 1915.[17] The ANZACs had constructed a coastal road at ANZAC Cove. This was extended by Turkish forces following the Allies' evacuation in 1915, and several repairs have been made since.

1.17 The main period of cemetery and memorial planning on the Peninsula took place in the 1920s under the direction of the Imperial (later Commonwealth) War Graves Commission (CWGC). There are currently 31 cemeteries and five allied memorials.

1.18 In 1973, the Turkish Government announced that 33 000 hectares on the southern tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula would become a designated National Park. The site covers the Gallipoli battlefield and the area of the Battle of Cannakale in the Dardanelles. It is included in the United Nations' List of National Parks and Protected Areas.

1.19 In 1997, on the initiative of the President of the Republic of Turkey, an international competition was launched to transform the area into a 'Peace Park'. The objective was to 'design a place devoted to peace and harmony', while respecting the site and the natural environment.[18] The winners, Norwegians Lasse Brogger and Anne-Stine Reine, were announced in 1998.

1.20 In 1999, the Australian and New Zealand Governments proposed an ANZAC Commemorative site. The sharp increase in visitations for the April ANZAC Day Service—from 4500 in 1995 to 8500 in 1999—required a move from the Ari Burnu War Cemetery.[19] In particular, there were concerns that the volume of visitors to the Cemetery was causing permanent damage to graves and plantings. In 1999, there were around 5000 people attending the last of the services at the Ari Burnu War Cemetery.[20]

1.21 In 2000, the Office of Australian War Graves (OAWG) constructed the ANZAC Commemorative site within the Battlefield Heritage Zone of the Peace Park. It is situated 300 metres north of the Ari Burnu Cemetery on North Beach, and accessed from the coastal road. The Australian Government committed $1.2 million to the project.[21] In April 2000, the first ANZAC Day ceremony at the new Commemorative site, between 9000 and 10 000 people attended services on the Peninsula. Of these people, only 2000 attended the ceremony at Ari Burnu.[22]

1.22 However, the new site also suffers from inadequate toilet facilities, lack of space for 20 000 visitors, and access roads with low traffic and parking capacity.

1.23 The accompanying map shows the main features of historic significance on the Gallipoli Peninsula, the remit of the Peace Park, and the two roads of interest to the inquiry.

Plate (ii)—The Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey

Source: Geoscience Australia.The Treaty of Lausanne 1923

1.24 The Committee and its witnesses acknowledge that construction on the Gallipoli Peninsula, and efforts to heritage list the area, are ultimately matters for the sovereign state of Turkey. The Gallipoli Peninsula is a part of the territory of Turkey.

1.25 However, many submissions also cited the Treaty of Lausanne 1923. The submission from the Department of Veterans' Affairs explains that the Treaty 'defines the boundaries of the ANZAC battlefield and grants rights to the (now) CWGC to safeguard the cemeteries and memorials on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Turkey retains overall sovereignty'.[23]

1.26 Part V, section 128 of the Treaty states:

The Turkish Government undertakes to grant to the Governments of the British Empire...and in perpetuity the land within the Turkish territory in which are situated the graves, cemeteries, ossuaries or memorials of their soldiers and sailors who fell in action...The Turkish Government undertakes further to give free access to these graves, cemeteries, ossuaries and memorials, and if need be to authorise the construction of the necessary roads and pathways.

1.27 In this context, Article 129 makes specific mention to 'the region known as ANZAC, Ari Burnu'. Article 135 states that the Turkish Government undertakes 'to maintain in perpetuity the roads leading to this land'.[24]

1.28 The Committee requested that officials from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade provide advice on Article 135, and its reference that 'representatives of the British, French or Italian Governments...shall at all times have free access thereto'. As discussed in the introduction, this request has been refused. Apart from the serious procedural implications of the refusal, it is difficult to understand given the level of public interest in the matter and the public right to know.

The Turkish Government's financial commitment to new roads

1.29 The Turkish Government has committed $A100 million to various activities on the peninsula, including the upgrade of roads and construction of new car parks. In May 2005, Mr Bulent Arinc, the President of the Turkish Grand National Assembly, announced that $A25 million has already been spent upgrading the coastal road.[25] The roadworks cover 6.3 kilometres, from Brighton beach in the south, past ANZAC Cove, Ari Burnu, the ANZAC Commemorative site, and up to Embarkation Pier (see map).

1.30 The rest of this report explains the need for this roadwork and the controversy surrounding its construction. It concludes with some recommendations for protecting the military heritage of the area.

Findings

- The significance of the 1915 Allied campaign at Gallipoli in the history of the Australian nation has experienced a resurgence of interest in recent years as a symbol of independence, nationhood, national ethos and identity.

- The significance of Gallipoli is reflected by strongly growing attendances at ANZAC Day ceremonies at ANZAC Cove over the last decade, and by a resurgence of interest and support for commemorative activities.

- In the lead-up to the centenary of the 1915 landing, public interest in Gallipoli is likely to grow.

- The symbolism and importance of Gallipoli has been reflected in extremely strong public reaction to events at Gallipoli early in 2005 both with respect to damaging roadworks, but also the events associated with the ANZAC Day ceremony on 25 April 2005.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page