When there is continuing disagreement between the House of Representatives and the Senate about a proposed law, the Governor-General has, in specific circumstances, the power to dissolve both houses simultaneously—a ‘double dissolution’. There have only been seven double dissolution elections since the opening of the first Federal parliament in 1901.

‘Dissolution’ is the term used for the action of ending a Parliament or a House of the Parliament. Under the Constitution, only the Governor-General has the power to take such action. By convention the Governor-General takes this action only on the advice of the Prime Minister of the day.

Dissolution of the House of Representatives

A House of Representatives may last for no more than three years from the date of its first meeting after an election. It then comes to an end automatically—it is said to expire.

The House may also be dissolved by the Governor-General (in practice on the advice of the Prime Minister) before the end of the three years. After the expiry or dissolution of a House, elections for the full membership of a new House are held at a general election.

In practice, dissolution of the House before the three-year maximum has been the norm. Only one House of Representatives has lasted for the maximum time allowed (3rd Parliament – 20 February 1907–19 February 1910).

Continuation of the Senate

Senators are elected from 1 July for a fixed period of six years (except those representing the territories, who serve for three years, with their terms tied to House of Representatives elections). Every three years half the membership of the Senate stands for election.

When the House expires, or is dissolved in normal circumstances, the Senate continues to exist. This is because Senators remain in office until the completion of their term and only half stand for election at any one time. The Senate can only be dissolved in accordance with the double dissolution provisions of the Constitution.

The Official Secretary of the Governor-General reading the proclamation to dissolve the House of Representatives and the Senate in May 2016

Double dissolution

Section 57 of the Constitution says:

If the House of Representatives passes any proposed law, and the Senate rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree, and if after an interval of three months the House of Representatives, in the same or the next session, again passes the proposed law with or without any amendments which have been made, suggested, or agreed to by the Senate, and the Senate rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree, the Governor-General may dissolve the Senate and the House of Representatives simultaneously. But such dissolution shall not take place within six months before the date of the expiry of the House of Representatives by effluxion of time.

Disagreement between the Houses over legislation

Proposed laws must be agreed to by both Houses of the Parliament. When the Government does not have a majority in the Senate, the situation can arise that the two Houses disagree over proposed legislation. In most cases, compromises are reached and amendments are made by one or the other House until the bill concerned is in a state acceptable to both.

A double dissolution may occur in situations where the Senate and House of Representatives are unable to agree over one or more pieces of legislation. The Constitution provides the double dissolution mechanism as a means of breaking a deadlock between the Houses when compromise is not achieved.

Procedure for a double dissolution

Section 57 of the Constitution sets out the steps which must take place before a double dissolution is possible, and the procedure for resolving a disagreement involving a proposed law originating in the House of Representatives:

- The House of Representatives passes a bill and sends it to the Senate.

- The Senate rejects the bill, or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree. The term ‘fails to pass’ has not been strictly defined and would be interpreted according to the circumstances at the time. The High Court has stated that a ‘reasonable time’ must be allowed.

- After an interval of three months, the House of Representatives passes the bill a second time and sends it to the Senate again. The bill reintroduced must be the original bill, except that it may be modified by amendments made, requested or agreed to by the Senate. The bill must be reintroduced within the same session of Parliament—a new session occurs after a prorogation (temporary suspension) or dissolution. In recent times it has been the practice for Parliaments to consist of one session only.

- The Senate again rejects the bill, or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree.

If these conditions have been met, the Governor-General may dissolve both houses. Elections are then held.

It is a matter for the Prime Minister to decide whether and when to advise to Governor-General to carry out a double dissolution. There is no constitutional necessity to do so, or to do so within any period of time. However, a double dissolution cannot occur within six months of the end of a three-year term of the House of Representatives.

Following a double dissolution

Once both houses are dissolved, elections are held for the full membership of both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The electorate is presented with the opportunity to change the composition of either House. There is the possibility the election will change the composition of the Senate (i.e. to give the government majority) or of the House (i.e. a change of government)—the deadlock may be broken in either direction.

Regardless of the outcome of the double dissolution election, there is no constitutional requirement for the new government to reintroduce a bill that was the cause of the double dissolution. Of the seven cases of a double dissolution election in the history of the Australian parliament, the government has reintroduced the relevant bill four times.

Depending on the outcome of the elections, the Houses may still disagree on the bill that was the cause of the double dissolution if it is reintroduced.

Continued disagreement—joint sitting

If the Houses disagree on the bill again after a double dissolution and elections for both Houses, the Governor‑General may convene a joint sitting of the Senate and the House of Representatives to enable the members of both Houses to vote together to resolve the matter. Because the House of Representatives has approximately twice as many members as the Senate, a joint sitting is likely to give a majority in the House the opportunity to outweigh the resistance of a majority in the Senate.

Joint sitting 1974

Procedure for a joint sitting

Like for a double dissolution, the steps for the procedure of a joint sitting are outlined by Section 57 of the Constitution.

- In the new Parliament the House of Representatives passes the bill again and sends it to the Senate. The bill may be reintroduced with or without amendments made, requested or agreed to by the Senate.

- The Senate again rejects the bill, or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree.

- The Governor‑General may convene a joint sitting of the members of both Houses. In practice, this would be done on the advice of the Prime Minister.

- The joint sitting votes on the bill as last proposed by the House of Representatives and on any amendments made by one House and not agreed to by the other. To be passed, amendments and the bill (as, and if, so amended) must be agreed to by an absolute majority—i.e. more than half of the total number of the members of both Houses (114 votes).

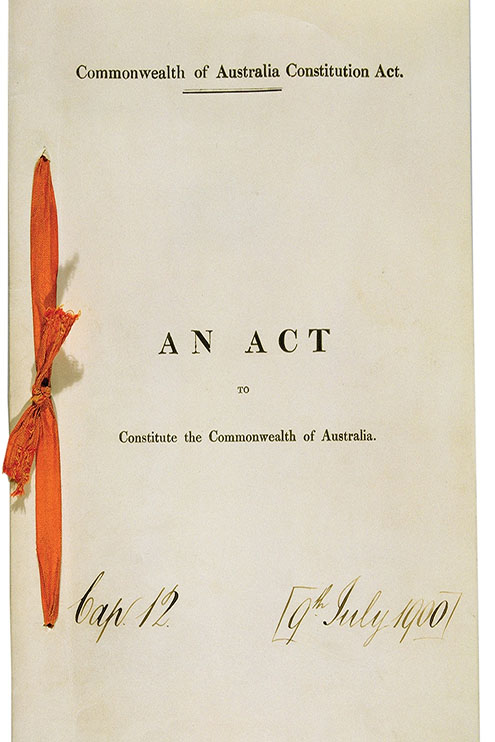

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act

Results of double dissolution elections

1914—the deadlock was broken by the Government losing its majority in the House as a result of the double dissolution election. The legislation was not reintroduced.

1951—the deadlock was broken by the Government gaining a majority in both Houses. The legislation was reintroduced and passed by both Houses without amendment.

1974—the Government was returned but did not gain a majority in the Senate. The disagreement between the Houses continued, resulting in a joint sitting at which the bills concerned were passed.

1975—the bills concerned were not reintroduced in the new Parliament. Unique circumstances applied in this instance. Following disagreement over the passage of a number of bills, the Government was dismissed by the Governor-General and a ‘caretaker’ government installed to enable passage of appropriation bills. The caretaker government then requested a double dissolution and was elected at the ensuing election. The bills providing the technical grounds for the double dissolution were not those of the caretaker government seeking the dissolution, but those of the Government dismissed by the Governor-General.

1983—the deadlock was broken by the Government losing its majority in the House.

1987—the Government was returned but did not gain a majority in the Senate. The bill concerned was reintroduced and again passed by the House but ultimately not proceeded with.

2016—the Government was returned but did not gain a majority in the Senate. The bills concerned were reintroduced and passed by both Houses after the House agreed to Senate amendments.

For more information

House of Representatives Practice, 7th edn, Department of the House of Representatives, Canberra, 2018, pp. 467–92.

Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 14th edn, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 2016, pp. 717–71.

About the House website: www.aph.gov.au/athnews.

X: @AboutTheHouse | Bluesky: @aboutthehouse.bsky.social |

Facebook: Aboutthehouseau | Instagram: @abouttheHouse

Images courtesy of AUSPIC.