Australia became a nation on 1 January 1901. The inauguration ceremonies began with a grand parade from Sydney’s Domain to Centennial Park, with approximately 500,000 people lining its route. At the ceremony itself, 100,000 spectators witnessed Governor-General Lord Hopetoun1 take his oath of office and swear in Australia’s first Prime Minister, Edmund Barton2, and his ministry.

According to the Sydney Morning Herald:

The crowds in all the city’s thoroughfares, the procession that threaded its way through the dense masses of the populace, the military display, all united to form a pageant as remarkable as it was historically significant. Soldiers of the finest regiments in the service of the Queen marched in the same ranks with Australian soldiers from all the colonies.3

The Governor General and the first Federal Ministry, January 1901, Crown Studios, Dixson Library. Courtesy of the State Library of NSW.

The Salvation Army’s Limelight Department documented the occasion, with Inauguration of the Australian Commonwealth becoming Australia’s first known feature length documentary. Heralded as ‘an overnight sensation’,4 the film was shown in theatres throughout Australia, Britain and Canada.5

Days of celebration pomp and pageantry followed, with church services, civic banquets, military displays, debates, sports carnivals, fireworks, bonfires and illuminations.6 Though the nation was now created in law, much work remained to create a true federal union. As the newly-appointed Commonwealth Attorney-General Alfred Deakin7 wrote anonymously in London’s Morning Post:

Sudden as the birth will be and richly endowed as is the new-born with the amplest charter of self-government that even Great Britain has ever conceded to her offshoots, much time and toil will be required before we can hope to actually enter and enjoy our inheritance …

The Constitution … contains merely the framework of government, whose substance and strength must come by natural growth …

[C]auses of controversy lie thickly around. These are likely to be multiplied and rendered bitter because a considerable portion of the electors of the Federal Parliament are not yet really allied in sentiment nor ripe for concerted action … [I]t may be taken for granted that the Commonwealth will not begin its reign without much friction, much misunderstanding, and even much complaint …

The Commonwealth Constitution will begin to take effect on the 1st of January, but everything which could make the union it establishes more than a mere piece of political carpentry will remain to be accomplished afterwards.8

Unknown, Town Hall at night. Sydney, from Federation Celebrations, 1901, Historic Memorials Collection, Parliament House Art Collections.

The uncertain path to Federation

In a celebrated 1891 speech NSW Premier Sir Henry Parkes9 proclaimed his vision for Australia: ‘one people: one destiny’10. However, Deakin later remarked that: ‘to those who watched its inner workings’ Federation ‘must always appear to have been secured by a series of miracles’, its fortunes having ‘visibly trembled in the balance twenty times'11.

The idea of an Australian general assembly was first proposed unsuccessfully in the 1840s12. Then from the 1860s a series of intercolonial conferences was convened, though proposals for a federal council received little support13. By 1883, growing concerns over French and German regional expansion saw the intercolonial convention adopt ‘a Constitution Bill’ which in 1885 became an ‘Imperial Act to establish a federal council’, comprising nominees from the Australian colonies, New Zealand, and Fiji14. With a mandate over regional relations, law enforcement, civil process and international fisheries15, the council suffered from a lack of united involvement and made ‘little use of its powers’ before ceasing in 1899.16

In February 1890, representatives from the Australian colonies and New Zealand assembled in Melbourne at the Australasian Federation Conference, agreeing that ‘the best interests and the present and future prosperity of the Australian Colonies will be promoted by an early union under the Crown’17. The following year, a National Australasian Convention adopted the name ‘Commonwealth’ for the proposed federation and agreed on a draft constitution, the Australian Constitution Bill 1891.18 Despite the growing economic depression, the energetic campaigning of Barton, Deakin and William McMillan19, alongside the Australasian Federation League (NSW) and the Australian Natives’ Association saw popular support remain strong.20 People’s conferences in Corowa in 1893 and Bathurst in 1896 further galvanised the movement, notwithstanding New Zealand’s withdrawal from the process.21

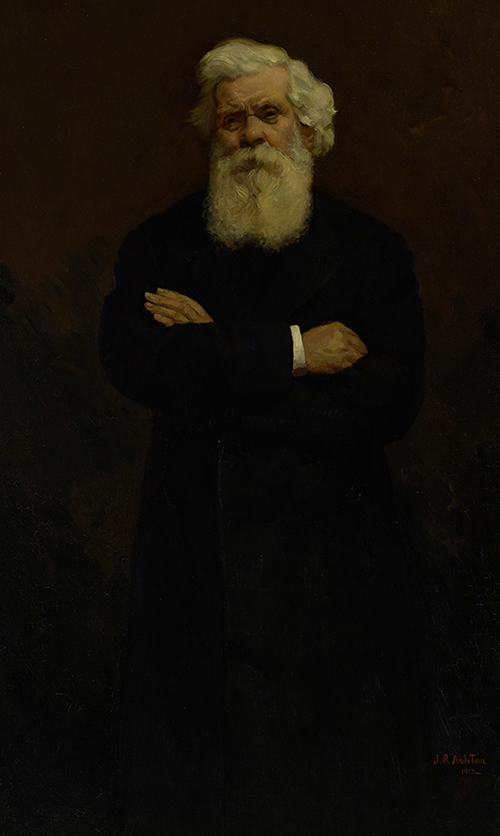

Julian Ashton (1851-1942), Henry Parkes, 1913, Historic Memorials Collection, Parliament House Art Collections.

English born Sir Henry Parkes (1815–96) served in the NSW colonial parliament for over 40 years (1854–95). He rose from childhood poverty to become five times Premier of NSW between 1872 and 1891, and remains its longest serving Premier. It is for his contribution to Australia’s Federation movement that Parkes is most remembered, though he died five years before his vision of ‘one people: one destiny’ was realised.22

When the Historic Memorials Committee resolved to commission portraits of the ‘Federal Nobilities’, the leading figures behind Federation, Henry Parkes was the first to be honoured.

Artist and educator Julian Ashton had previously painted a portrait of Parkes, purchased by the NSW government in 1890 for the NSW National Art Gallery (now Art Gallery of NSW). The Committee decided to commission Ashton to paint a replica of this portrait, which had been described by a reviewer as ‘a grand work … wherein the power of the artist is shown fully worthy of the subject in hand, Australia’s greatest living statesman’. Ashton’s original portrait is now held in the Sir Henry Parkes Memorial School of Arts in Tenterfield, NSW, the site of Parkes’s 1889 Tenterfield Oration, with replica portraits held in the Historic Memorials Collection and the NSW Parliament Collection.23

The 1895 Premiers’ Conference proposed a new constitutional convention to progress the 1891 draft Bill24 which occurred two years later across three sessions: Adelaide and Sydney in March–May and September 1897 respectively, and in Melbourne in January–March 1898.25

Following the colonial parliaments’ endorsement, the draft constitution was submitted at a series of referenda. It received strong majorities in Victoria, SA and Tasmania, but failed to achieve the minimum benchmark for support in NSW.26 Queensland and WA declined to participate over concerns that their smaller populations were disadvantaged within the current proposal. Following changes to the draft Bill in January 189927 all states reached agreement except WA, which delayed support until its 31 July 1900 referendum, three weeks after the Constitution became law.28 The Brisbane Courier declared:

Australia is born: The Australian nation is a fact … Now is accomplished the dream of a continent for a people and a people for a continent. No longer shall there exist those artificial barriers which have divided brother from brother. We are one people – with one destiny.29

However, to come into effect the draft constitution required British approval, which occurred on 5 July 1900.30 In London to facilitate the Bill’s passage, Deakin later described himself and colleagues Barton, James Dickson31, Charles Kingston32 and Sir Philip Fysh33 as ‘to some extent the lions of the season … [who] roared their best for the Bill’.34

The Royal Commission of Assent to the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK) signed by Queen Victoria on 9 July 1900, 1900. Official Gifts Collection, Parliament House Art Collections. The table, inkstand and pen used by Queen Victoria when signing the Royal Commission of Assent, shown with a facsimile of the Royal Assent and Seal. Official Gifts Collection, Parliament House Art Collections.

The ensuing Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK)35 became law when Queen Victoria36 signed the Royal Commission of Assent on 9 July 1900.37 The Queen presented a duplicate copy, alongside her signing pen, inkstand, and table to Barton at a ceremony at Windsor Castle.38 On 17 September 1900, Her Majesty proclaimed that the Commonwealth of Australia would come into existence on 1 January 1901.39 She also issued Letters Patent on 29 October 1900 appointing Lord Hopetoun, formerly Governor of Victoria, as Australia’s first Governor-General.40

The Queen signed her assent in duplicate so that a copy could be brought back to Australia, and presented it (together with the pen, inkstand and table that she used when signing the Royal Commission of Assent) to Edmund Barton at a ceremony at Windsor Castle.

The table was a centrepiece at the Centennial Park ceremony at the inauguration of the Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901. The writing table is today an important part of the Parliament House Art Collection and is used on ceremonial occasions.

‘The Federation Kiosk, Centennial Park, Sydney at the proclamation of Federation’, 1901. Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia (NAA A1200-L83907; 11404539). The Federation Kiosk at Sydney’s Centennial Park, 1 January 1901. Here the proclamation of the Commonwealth of Australia was read to the assembled crowd, as the first Governor-General, Lord Hopetoun, and the first federal ministry took their oaths of office around Queen Victoria’s writing table.

The first Ministry

Arriving in Sydney on 15 December 1900, Lord Hopetoun quickly set about commissioning his ministry. The selection garnered much media speculation, with the Argus surmising:

Attention is now concentrated upon the formation of a Ministry … It is expected that [Lord Hopetoun] will lose no time in entrusting someone with the task of forming a Ministry, and there is no variation in the general belief that Mr Barton is the man upon whom the honour is sure to be conferred … The Lyne party here still professes to be confident that the Premier of the senior colony cannot be passed over, and there are others who strongly hold that as Mr Reid, if he had been Premier of the colony, could not have been passed over, the mere political accident of his being out of office cannot outweigh his other strong claims.41

Hopetoun first invited NSW Premier William Lyne42 to form a ministry, despite Lyne’s well-known ambivalence regarding Federation. His choice was regarded by many as a misstep. The British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain43 cabled: ‘Great surprise expressed at choice of Lyne instead of Barton. Please give reasons’44. Sir John Anderson45 of the Colonial Office confided to Barton:

Hopetoun has fairly taken our breath away by asking Lyne to form a Govt …

[W]hen we discussed the matter before he left, I understood that like us here and most other people he was looking elsewhere for his first Minister.46

Reflecting acerbically on Hopetoun’s recent bout of typhoid fever, Kingston attempted to console the overlooked Barton, writing that the Governor-General’s illness ‘has no doubt kept him busy with his bowels, & left him no time to acquaint himself with Australian sentiments’47. For his part, the former NSW Premier George Reid48 felt that ‘the Governor-General has taken the only course fairly open to him’, and asserted that ‘if Mr Barton had been sent for I would have felt rightly aggrieved’49.

As a staunch ally of Barton, Deakin convinced the leading federalists to boycott a Lyne government. Lyne being unable to form a ministry, Hopetoun turned to Barton as Australia’s first Prime Minister50. Barton’s first ministry was announced on 30 December, with the Bulletin assessing:

Australia certainly owes a debt of gratitude to Lyne for his actions in the matter. A man who was less straight in his dealings than the lengthy William would almost certainly have stuck to the opportunity which accident threw in his way, to the great probable detriment of the country. When Lyne found that neither Barton, Turner, Deakin nor Kingston would serve under him, it became evident that he could not form a strong Government – the sort of Government that Australia expected. But, all the same, Lyne could have formed a Government. In fact he could have formed 25 Governments. There were probably 150 politicians in Australia who would have almost broken their necks getting to the telegraph-office to wire their acceptance of any portfolio that Lyne chose to offer them.51

References

1.C Cunneen, ‘Hopetoun, seventh Earl of (1860–1908)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed 12 July 2021.

2. M Rutledge, ‘Barton, Sir Edmund (Toby) (1849–1920)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1979, accessed 12 July 2021.

3. ‘Yesterday’s celebration’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 January 1901, p. 8, accessed 12 July 2021.

4. J Fitzgerald, On message: political communications of Australian Prime Ministers 1901–2014, Clareville Press, Mawson, 2014, p. 22.

5. E Taggart-Speers, ‘Inauguration of the Commonwealth (1901)’, Australian Screen, National Film and Sound Archive, accessed 1 June 2018.

6. Fitzgerald, op. cit., p. 21.

7. R Norris, ‘Deakin, Alfred (1856–1919)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed 12 July 2021.

8. A Deakin, ‘Problems ahead: the Boer War’, in D Heriot, ed., From Our Special Correspondent: Alfred Deakin’s letters to the London Morning Post: Volume 1: 1900–1901, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2020, pp. 5, 6 and 8, accessed 23 July 2021.

9. AW Martin, ‘Parkes, Sir Henry (1815–1896)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1974, accessed 12 July 2021.

10. H Parkes, ‘Speech of The Hon. Sir Henry Parkes, G.C.M.G., to the citizens of Sydney in the Gaiety Theatre’, Saturday June 13, 1891, “One people: One Destiny”’, Turner and Henderson, Sydney, 1891; ‘Sir Henry Parkes (1815–1896)’, Parliament of NSW; ‘Student Learning Centre: Henry Parkes’, Parliament of NSW, Parliamentary Education and Engagement. Websites accessed 21 October 2021.

11. A Deakin, The federal story: the inner history of the federal cause 1880–1900, JA La Nauze ed., 2nd edition, Melbourne University Press, Parkville, 1963, p. 173.

12. J Quick & RR Garran, The annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1901, pp. 79ff, accessed 23 July 2021; R Murray, The making of Australia: a concise history, Rosenberg Publishing, Kenthurst, NSW, 2014, pp. 153ff.

13. AW Martin, Henry Parkes: a biography, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1980, pp. 315, 383; ‘Australian Federal Council’, The Age, 1 February 1881, p. 3; Intercolonial Conference, Minutes of proceedings of the Intercolonial Conference held at Sydney January 1881 presented to both houses of parliament by His Excellency’s command, Melbourne, 1881. Websites accessed 23 July 2021. Parkes had first moved such a motion at his first intercolonial conference in 1867 but this, like the 1881 proposal, came to nothing. See Martin, Henry Parkes: a biography, op. cit., p. 383; Quick & Garran, op. cit., pp. 102–03.

14. Martin, Henry Parkes: a biography, op. cit., p. 384; Intercolonial Convention, Report of the proceedings of the Intercolonial Convention, held in Sydney, in November and December 1883, Sydney, 1883; ‘Federal Council Bill’, The Argus, 10 December 1883, p. 5; Quick & Garran, op. cit., pp. 111ff. Websites accessed 23 July 2021.

15. SB Kaye, ‘Forgotten source: the legislative legacy of the Federal Council of Australasia’, Newcastle Law Review, 1(2), 1996, p. 60, accessed 23 July 2021.

16. Ibid. See also Quick & Garran, op. cit., p. 113.

17. ‘Address’, ‘Official record of the proceedings and debates of the Australasian Federation Conference, 1890, held in the Parliament House, Melbourne’, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1890, p. iv, accessed 23 July 2021.

18. ‘Official report of the National Australasian Convention Debates, Sydney, 2 March to 9 April, 1891’, Records of the Australasian Federal Conventions of the 1890s, Government Printer, Sydney, 1891, accessed 23 July 2021.

19. AW Martin, ‘McMillan, Sir William (1850–1926)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1986, accessed 14 July 2021.

20. B de Garis, ‘How popular was the popular Federation movement?’, in Papers on Parliament, 21, Department of the Senate, December 1993, accessed 23 July 2021.

21. N Aroney, ‘New Zealand, Australasia and Federation’, Canterbury Law Review, 16, 2010, pp. 31–46; FLW Wood, ‘Why did New Zealand not join the Australian Commonwealth in 1900–1901?’, New Zealand Journal of History, 2(2), 1968, pp. 115–29; A Chan, ‘New Zealand, the Australian Commonwealth and “plain nonsense”’, New Zealand Journal of History, 3(2), 1969, pp. 190–95; M Fairburn, ‘New Zealand and Australasian Federation 1883–1901: another view’, New Zealand Journal of History, 4(2), 1970, pp. 138–59; PM Smith, ‘New Zealand federation commissioners in Australia: one past, two historiographies’, Australian Historical Studies, 122, 2003, pp. 305–25. Websites accessed 23 July 2021.

22. Parkes, op. cit.

23. 'The Art Society’s Exhibition’, The Sydney Mail and NSW Advertiser, 12 October 1889, p. 812; ‘Historic Memorials Committee meeting 13 Feb 1912’, National Archives of Australia, NAA A457, B508/7, p. 153; ‘Mr. Julian Ashton and the Art Gallery’, The Daily Telegraph, 3 March 1894, p. 10.

24. ‘Conference of Premiers: Australian Federation: Unanimity of Feeling’, The Argus, 30 January 1895, p. 5; ‘The Federal Scheme: Proposals of the Premiers: the Referendum Adopted’, The Argus, 1 February 1895, p. 7; ‘The Federal Gatherings: The Premiers’ Conference: the Federation Bill’, The Argus, 7 February 1895, p. 5. Websites accessed 23 July 2021.

25. ‘Official report of the National Australasian Convention debates Adelaide, March 22 to May 5, 1897’, Records of the Australasian Federal Conventions of the 1890s, Government Printer, Adelaide, 1897; ‘Official record of the debates of the Australasian Federal Convention, second session, Sydney, 2–24 September, 1897’, Records of the Australasian Federal Conventions of the 1890s, Government Printer, Sydney, 1897; ‘Official record of the debates of the Australasian Federal Convention, third session, Melbourne, 20 January – 17 March, 1898’, Records of the Australasian Federal Conventions of the 1890s, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1898. Websites accessed 23 July 2021.

26. Australian Bureau of Statistics & S Bennett, ‘Australian Federation’, Year Book Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, 2001, accessed 23 July 2021.

27. Quick & Garran, op. cit., pp. 213ff; Murray, op. cit., pp. 160ff.

28. ‘Federation factsheets: the Referendums 1898–1900’, Australian Electoral Commission; ‘A nation at last: Constitutional Centre of Western Australia exhibition: Western Australia says “yes”’, The Constitutional Centre of Western Australia. Websites accessed 23 July 2021.

29. ‘The coming Commonwealth’, The Brisbane Courier, 4 September 1899, p. 5.

30. Australian Senate, ‘For peace, order and good government – the first Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia: origins of the Australian Parliament’, Australian Senate, accessed 23 July 2021.

31. DD Cuthbert, ‘Dickson, Sir James Robert (1832–1901)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed 14 July 2021.

32. J Playford, ‘Kingston, Charles Cameron (1850–1908)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed 14 July 2021.

33. Q Beresford, ‘Fysh, Sir Philip Oakley (1835–1919)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed 14 July 2021.

34. Deakin, ‘The federal story, op. cit., p. 154.

35. ‘Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK)’, accessed 23 July 2021.

36. ‘Victoria (r. 1837–1901)’, Royal Family, accessed 14 July 2021.

37. ‘Royal Commission of Assent 9 July 1900 (UK)’, accessed 23 July 2021.

38. The table was to be a centrepiece at the Centennial Park ceremony to inaugurate the Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901. Made of English oak, the Queen Victoria writing table is today an important part of the Parliament House Art Collection and is used on ceremonial occasions.

39. ‘Royal Assent’, photograph, National Archives of Australia, NAA A13417.1, 1901, accessed 26 July 2021.

40. ‘Documenting a democracy: Letters Patent Constituting the Office of Governor-General 29 October 1900 (UK)’, Museum of Australian Democracy, accessed 23 July 2021.

41. ‘First federal ministry’, The Argus, 17 December 1900, p. 5, accessed 23 July 2021.

42. C Cunneen, ‘Lyne, Sir William John (1844–1913)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1986, accessed 14 July 2021.

43. GW Poole, ‘Joseph Chamberlain’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed 14 July 2021.

44. ‘Telegram from Secretary of State for the Colonies requesting reasons for choice of W.J. Lyne instead of Edmund Barton’, National Archives of Australia, NAA-A6661-1055; 421675, 1900, accessed 23 July 2021. By the time Hopetoun responded to the cable, Lyne had failed to form a ministry and he had commissioned Barton. C Cunneen, King’s men: Australia’s governors-general from Hopetoun to Isaac, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1983, p. 10.

45. ‘About people: Death of Sir John Anderson’, The Age, 26 March 1918, p. 8, accessed 26 July 2021.

46. ‘Series 1: Correspondence 1827–1921, Correspondence 1900 Item 739–40: 21 December Sir John Anderson to Edmund Barton – Part 1’, Papers of Sir Edmund Barton, nla.ms-ms51-2-949-s1, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1900, accessed 23 July 2021.

47. ‘Series 1: Correspondence 1827–1921, Correspondence 1900, Item 735: C Kingston Letter to Edmund Barton’, ibid., accessed 26 July 2021.

48. WG McMinn, ‘Reid, Sir George Houstoun (1845–1918)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1988, accessed 14 July 2021.

49. ‘The federal premier’, The Argus, 20 December 1900, p. 5, accessed 23 July 2021.

50. See JA La Nauze, ‘The Hopetoun Blunder’, in H Irving and S MacIntyre, eds, No ordinary act: essays on Federation and the Constitution by J.A. La Nauze, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, 2001.

51. ‘Plain English: Edmund Barton is “sent for”’, The Bulletin, 5 January 1901, p. 6, accessed 23 July 2021.