Appendix E - Work of Committee of Privileges: Some Facts and Figures

References, general

inquiries and advisory reports to November 2005

Since 1966, 127

matters have been referred to the Committee of Privileges and 124 reports have

been tabled, including five in 2005. Sixteen matters have been referred since

the committee’s previous general report on its operations, Report no. 107,

tabled in August 2002, and 17 reports have been tabled, including four advisory

reports.

As advised in

previous general reports (nos 35, 62, 76 and 107), the committee may combine

matters in a single report or report on them separately. Hence the number of

reports tabled does not correspond to the number of matters referred.

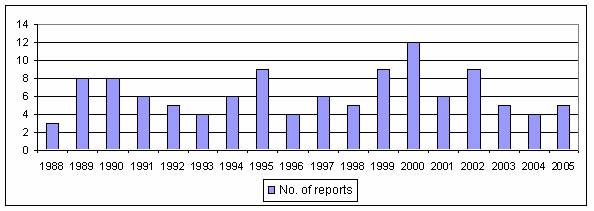

Figure E.1 Number of reports tabled per

year, 1988 – 2005

The committee’s

activities prior to 1988 were spasmodic, with little or no ‘bunching’ of

reports: reports were tabled in 1971, 1975, 1978, 1979 (2), 1981, 1984, 1985

(2) and 1986. Since 1988, however, many more demands have been placed on the

committee. As figure E.1 discloses, the busiest year to date has been 2000,

during which twelve reports were tabled. Reports can encompass more than one

reference with, for example, report no. 74 covering six references. As figure

E.1 also discloses, the committee’s workload is heavily influenced by the

election cycle. In years in which federal elections have been held (1990, 1993,

1996, 1998, 2001 and 2004) its activities have been reduced.

Since the passage of

the privilege resolutions, including the introduction of the right-of-reply

procedure, in 1988, the committee has tabled 45 right-of-reply reports compared

with 51 reports on possible contempts and 18 general or advisory reports.

Figure E.2 shows how the types of reports have fluctuated within a fairly

narrow band in those 18 years. In 2005, three reports dealing with possible

contempts have been tabled, along with one advisory report and one

right-of-reply report.

Figure E.2 Reports by report type 1988-2005

Conduct of inquiries

On receiving a

reference from the Senate, the Committee of Privileges normally seeks, in

writing, inputs from the persons involved. It provides them with all available

evidence and invites a response. Such responses often elicit more questions

from the committee, which seeks to answer them by providing the further

documentation it has received from the complainant to the other persons

involved, and vice versa, and inviting further written submissions. Claim and

counterclaim can be traded through the committee until it is satisfied it has

sufficient reliable evidence on which to reach its conclusions. In the event

that the committee considers that it needs to hear evidence in person from

those involved, it will invite them to a public hearing. This is the exception,

however, rather than the rule. Since its inception, the committee has held

public hearings into 12 matters, involving 20 days of public hearings; since

the passage of the privilege resolutions in 1988, 13 days of public hearings

have been held involving nine cases.

The length of time

taken by the committee to complete an inquiry depends on a number of factors:

the inherent complexity of the reference; the number of references under

consideration simultaneously; the promptness of responses from participants;

the interruptions brought about by parliamentary elections; the vagaries of the

parliamentary calendar; and the type of reference. From reference to report,

the committee’s inquiries have taken from one day (Reports nos 34, 38 and 97)

to 25 months (Report no. 67). The average duration of the 45 right-of-reply

inquiries has been 28 days; 33, or 73 per cent, have been completed within a

month and 12, or 27 per cent, within one week. Possible contempt matters may

take considerably longer, on average just over 8 months.

Contempt references

Since 1966, the

Committee of Privileges has tabled 58 reports on cases of possible contempt,

based on 70 references from the Senate. In some cases, more than one type of

contempt can be involved in the one inquiry; in other cases, the committee has

elected to table together in a single report the results of its inquiries into

several distinct references with similar features, such as the six references

relating to the unauthorised disclosure of documents in report no. 74.

The committee has,

for the purposes of this summary, recognised four broad types of possible

contempt: the provision of false or misleading evidence to a senator or a

Senate committee; the unauthorised disclosure of documents, oral evidence or

reports of the Senate or a Senate committee; interference with witnesses,

namely cases in which persons giving information to a senator or a Senate

committee have been threatened with some form of reprisal or have been

penalised in some way for giving, or preparing to give, such information or

evidence; and matters relating to a senator, such as molestation or harassment

of a senator, attempts to influence a senator’s conduct and matters relating to

senators’ interests..

Since 1966, there

have been 22 completed cases relating to possible unauthorised disclosure of

committee reports or proceedings. Allowing for multiple categorisation, the

disclosures in question were reports (2), draft reports (12), submissions (4),

in camera evidence (4), proposed amendment (1), deliberations (2), documents

(1) and legal opinion (1). In the same period there have been 21 completed

cases relating to possible interference with witnesses, 15 of possible false or

misleading information and nine of matters relating to a senator. A breakdown

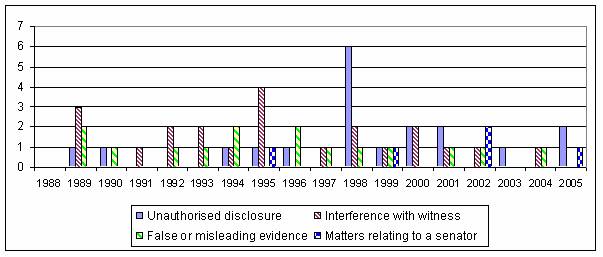

of possible contempt cases by type of contempt from 1988 onwards is shown in

Figure E.3. As that figure shows, the types of possible contempt referred vary

considerably from year to year. Of the three possible contempt reports tabled

in 2005, one has been a matter relating to a senator, and two have covered

three cases of possible unauthorised disclosure of draft committee reports or

deliberations.

Findings

of contempt and penalties imposed

Of 70 possible

individual contempt references within 58 contempt reports, contempt has been

found in 14 cases, six of them in the last six years. In the majority of the

earlier cases, the committee concluded that the contempt was inadvertent and

that the perpetrator(s) acted out of ignorance of the possible parliamentary

privilege consequences. This appears to be increasingly not the case, however.

In two cases a

penalty has been applied: the committee’s first report, in 1971, recommended a

reprimand, which was duly administered by the President in the Senate chamber;

while its 99th report recommended a reprimand, which was

administered in writing by the President. In three other instances, the

committee has recommended a conditional penalty: a fine if there is a reoffence

within the life of the Parliament (Report no. 8); prosecution, if the source of

the leak is disclosed (Reports nos 54 and 99); and the publisher’s access to

Parliament House to be curtailed if there is a reoffence (Report no. 99).

Figure E.3 Possible contempt matters by

contempt type 1988-2005

Public

officials’ involvement

Since the

committee’s inception, of the 63 cases broadly categorised as involving

possible contempt, 31 have involved in some capacity public servants, statutory

officers or staff of government agencies at federal, state or local government

level. In twenty cases, the possible contempt question related to the

activities in their official capacity of the public officials concerned.

While public

officials constitute the largest category of persons against whom possible

contempt allegations have been made, other groups are also significant. Members

of Parliament themselves and/or their staff are increasingly being involved in

possible contempts (15 cases); followed by journalists or publishers (8 cases);

universities, the police service and banks or credit unions have been involved

in two each; with the remainder comprising private individuals from a variety

of occupations.

Geographic

source of references

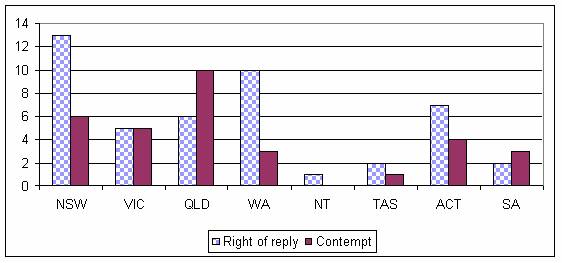

The majority of the committee’s

references is generated partly or solely from parliamentary committee activities,

particularly in their dealings with federal government departments, agencies or

ministers’ offices. Possible contempts which took place outside the parliament

are shown in Figure E.4, as is state or territory of residence of the person or

organisation seeking redress under the Senate’s right-of-reply procedures. Since 1988, every state and

territory has been the source of at least one reference involving possible

contempt, while all but the Northern Territory have contributed at least one

right-of-reply case.

Figure E.4 State and Territory source of

references 1988-2005

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page