Chapter 2 - Legal Aid Funding

2.1

This chapter discusses:

-

the

recent history and levels of Commonwealth and State and Territory

funding to Legal Aid;

-

the funding model used to determine the

distribution of Commonwealth funding;

-

the application of Commonwealth priorities and

guidelines in granting Commonwealth funds;

-

the breakdown of funding by type of matter:

criminal, family and civil;

-

specialist legal services;

-

the need to recognise the relationship between

"law and order" legislation with the resulting increase in demand for

legal aid; and

-

the Commonwealth/State dichotomy.

Recent history of funding to legal aid

2.2

Prior to 1997 the legal aid commissions (LACs) of each

state and territory were responsible for determining their own budget

priorities and expenditure. The Commonwealth participated in such decisions

through the Commonwealth Attorney-Generals representation on the board of LACs.

In 1996 the Commonwealth withdrew from this arrangement, and since July 1997

the state and territory legal aid commissions have been restricted to

allocating Commonwealth funding to matters arising under Commonwealth laws.

2.3

This funding arrangement is referred to as a

purchaser/provider arrangement, as under the legal aid agreements the

Commonwealth sets the priorities, guidelines and accountability requirements

regarding the use of Commonwealth funds.

2.4

In its Second

Report[1]

the Committee expressed its basic disagreement with the Commonwealth

Government's decision no longer to accept responsibility for the funding of any

matters arising under state and territory laws. The Committee reiterated its

concern in its Third Report.[2] The Committee

also expressed concern at the level of Commonwealth funding for legal aid.[3]

2.5

In 1996/97 the level of Commonwealth funding for legal

aid was $128.3 million. With the introduction of the new purchaser/provider agreement

Commonwealth funding was reduced to

$109.68 million in 1997/98, and to $102.84 million in 1998/99.[4]

2.6

On 15

December 1999, the Commonwealth Attorney-General announced that the

Commonwealth would provide $64 million in additional legal aid funding

nationally over four years, commencing 2000/2001. Commonwealth funding for

legal aid nationally in 2003/04 was $126.48 million.[5] The current

legal aid agreements expire on 30 June

2004.

2.7

In the 2004/05 budget the Government increased

Commonwealth funding of legal aid by $52.7 million over four years.[6] In a media

release regarding the Budget, the Attorney-General announced:

Additional funds will be available to State and Territory legal

aid commissions when they enter new legal aid agreements which are currently

being negotiated from 1 July 2004.

In return, the Government will be seeking timely reporting and

greater financial accountability from legal aid commissions.[7]

Levels of overall Commonwealth funding

2.8

The Law Council of Australia noted that although the

current four year funding agreements included an increase of funding of $64

million over the four year period, the level of Commonwealth funding in 2003/04

($126 million) was less than the level of funding in 1996/97 ($128 million), due

to the massive cuts to Commonwealth funding in 1997.[8]

2.9

It should also be noted that in real terms, the level

of funding in 2003/04 is substantially less than that provided in 1996/97.

After taking account of inflation, $128 million in 1996/97 is actually $153

million in real terms for 2003/04. This means that in real terms, the 2003/04

Commonwealth funding is $27 million less than it was in 1996/97.

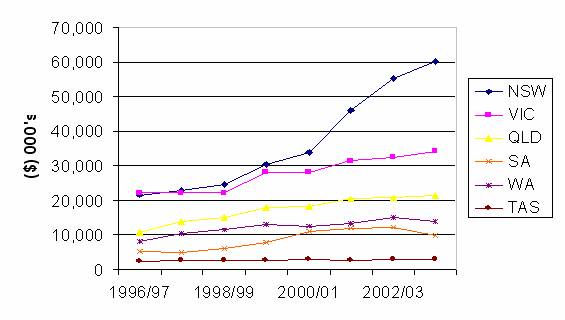

2.10 Figure

1.1 below shows the history of Commonwealth funding for legal aid for the years

1995/96 2003/04.

Figure 1.1

Commonwealth Funding for Legal Aid

Source: Based on figures

provided in correspondence from Commonwealth Attorney-General's Legal

Assistance Branch to the Committee dated 9 February 2004.

2.11 National

Legal Aid (NLA), which comprises the Directors of each state and territory LAC

also noted that funding had only returned to the levels of 1996/97. NLA argued

further that due to increased costs of service delivery, there has actually

been a decrease in the quantity of services being delivered:

The additional $63m legal aid funding for 2000-2004, given CPI

factors, was no more than an attempt to return to levels prior to the 1996

funding reduction. It should be noted that the $63m has not been indexed and,

while the cost of providing legal services has and will continue to increase,

the increased funding is not keeping pace with increases in these costs.

Whilst the quality of legal service has not been affected by the

cuts, the quantity and extent of that service has. The so called

purchaser/provider approach has added an additional layer of administration

and financial accountability for all Commissions.[9]

Levels of state and

territory funding to legal aid

2.12 In

its response to the Committee's Third

Report, the Government criticised the Committee's report for not adequately

detailing the levels of funding contributed by states and territories to legal

aid.[10]

2.13 As

noted above in Figure 1.1, Commonwealth funding to legal aid dropped steadily

from 1996 to 2000. The four year funding package implemented in 2000 has meant

that in 2004, funding has returned to below what it was in 1996 (again, it

should be noted that in real terms it is $27 million less than it was in 1996/97).

In contrast State and Territory contributions to legal aid have, in the main,

steadily increased from 1996 to 2004.

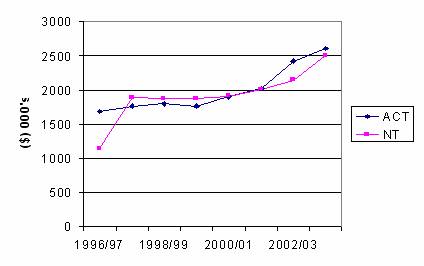

Figure 1.2 State

Funding of Legal Aid

Source: Based on figures from National

Legal Aid website, accessed 10 March 2004: http://www.nla.aust.net.au

Figure 1.3 Territory

Funding of Legal Aid

Source: Figures for State and Territory Funding from

National Legal Aid website, accessed 10 March 2004: http://www.nla.aust.net.au, Commonwealth

funding figures from correspondence from Commonwealth Attorney-General's Legal

Assistance Branch to the Committee dated 9 February 2004

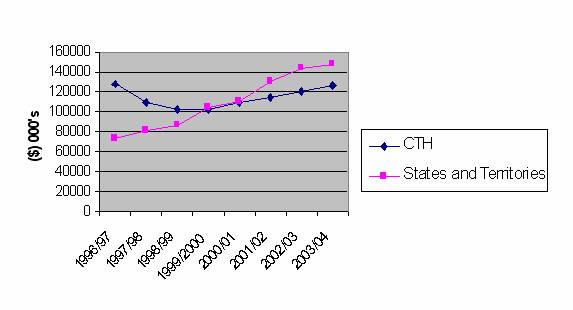

2.14 The

Government's introduction in 1996 of the Commonwealth/State funding dichotomy

was intended to move funding responsibilities to the jurisdiction within which

a matter arose. The Commonwealth would only fund matters arising under

Commonwealth law, whilst the States and Territories would fund matters arising

under their laws. Prior to 1996 the Commonwealth made a proportionately greater

contribution to legal aid than the States and Territories, since that time this

has been reversed, as the following figure shows.

Figure 1.4 State vs

Commonwealth funding of legal aid

Source: Based on figures from National

Legal Aid website, accessed 10 March 2004: http://www.nla.aust.net.au

Differences in Commonwealth funding to each State and

Territory

2.15 Funding

between the state and territory LACs is currently distributed under a 1999 funding

model that was based on research conducted by John Walker Consulting Services

and Rush Social Research. Submissions from each state and territory LAC

lamented that there is an insufficient level of Commonwealth funding.[11] Some

commissions also commented on the model used (discussed in more detail in the

next section) and the inequality of Commonwealth related legal aid services

that are available to citizens in each state and territory.

2.16 Legal

Aid Western Australia argued that

in per capita terms, 25% fewer people obtain legal representation to resolve a

family law matter in Western Australia

than do the national average.[12] It also noted

that Western Australia is the

lowest funded state or territory on a per capita basis, and as a result has the

highest refusal rate on applications received.[13] It also

pointed out that in real terms, per capita Commonwealth funding to Western

Australia has decreased by 28% over the last ten

years.[14]

2.17 The Victorian Department of Justice explained

that in 2003/04 NSW can expect to receive 50% more funding than Victoria,

despite only having a 36% greater population, and that Victoria can expect only

8% more funding than Queensland, despite the fact that Victoria has 31% more

people.[15]

2.18 Victoria

Legal Aid commented that in addition to different funding levels, the different

practices of each Commission (in relation to debt recovery and in the way they

apply the Commonwealth guidelines) can mean that citizens in each state and territory

face unequal chances of receiving Commonwealth related legal aid:

Victoria Legal Aid has

a very strong capacity to fund family law matters, whereas other states, such

as Western

Australia and Tasmania, on a regular basis have to say to applicants for aid for family law

matters: Im sorry. Your application meets the means test, the merits test and

the guidelines test, but we just do not have the money to fund you. So if you

are a Victorian with a family law matter you are in luck, but if you are in Western Australia you may well be in trouble.[16]

The funding model

2.19 There

were substantial criticisms of the model used to distribute Commonwealth funds.

The criticisms involved both in-principal objections to its assumptions and

methodology as well as specific errors in its application.[17]

2.20 The

Victorian Department of Justice and Victoria Legal Aid criticised three aspects

of the model, as well as general factors: unmet need, the 'suppressed demand'

factor and the 'average case cost' factor.

2.21 The

first criticism was that the model was based on the number of applications to LACs

and hence assessed met need and did not attempt to assess unmet need.[18]

2.22 The

second criticism related to the 'suppressed demand' factor used in the model.

The 'suppressed demand factor' seeks to account for reductions in demand for

legal aid, as a result of publicity regarding a lack of available funds:

The philosophy behind

that weighting was that in 1995, 1996 and 1997 the publicity in some

jurisdictions about the drastic cuts to legal aid was so severe that the demand

for legal aid in some jurisdictions was suppressed. It was an entirely

speculative exercise that that was the case. To apply a demand suppression

factor to only three of the eight jurisdictions was also entirely speculative

and to apply the weighting according to 10 per cent was entirely speculative.[19]

2.23

A

representative of the Attorney-General's Department explained the 'suppression

factor' in the following way:

I think it could be

described this way: due to publicity about levels of legal aid, people may not

have been making applications for legal aid in anticipation that they would not

be successful. A suppression factor was built into the model to increase

anticipated demand. It was adding in so you could anticipate that without that

suppression factor more applications would have been coming in some

jurisdictions.[20]

2.24 The

third criticism made by the Victorian Department of Justice related to the

average case cost factor included in the model:

The average case cost

element beggars belief, in terms of its logical foundations. It runs according

to this: if in a particular jurisdiction a legal aid commission has to pay a

higher average case cost to buy the service for the legal aid applicant, then

logically that commission can only afford to purchase fewer legal aid services.

If a commission can only purchase fewer legal aid services it must have a lower

level of demand, which therefore justifies lower levels of funding. That is the

way the average case cost factor was applied in the 1999 funding formula, and

it is a nonsense.[21]

2.25

In

evidence, the Attorney-General's Department explained the 'average case cost'

factor in the following terms:

The cost per case

factor was included because it was felt at the time that it reflected a

significant inverse statistical correlation of the cost per case with demand

for legal aid and as costs go up, depending on the cost per case, a legal aid

commission would be able to meet less demand and that would have an ongoing

impact on demand. The rationale for it is set out in the report of the model.[22]

2.26 Mr

Tony Parsons,

Managing Director of Victoria Legal Aid, argued that the model included

substantial errors. He pointed out that where the model sought to include

population figures of women, it erroneously included the population figures of

men.[23] He

also pointed out the population figure of people from non-English speaking

backgrounds was not based on Australian Bureau of Statistics figures, and hence

underestimated the population.[24] Victoria

Legal Aid expressed concerns over the model and noted the reduced funding that Victoria

had suffered as a result:

We have contacted the

creators of the modelRush-Walker developed the model for the Commonwealth in 1999and they have

confirmed those errors. So in the last four years, the Commonwealth has

distributed something like $450 million nationally for legal aid according to a

flawed funding distribution formula. Victoria takes a very strong stance on this because Victoria was the great loser from that distribution

model. In the last four yearsthe life of the agreement that was controlled by

that funding distribution modelWestern Australias funding increased by 30 per

cent, South Australias by nearly 20 per cent, Queenslands by 33 per cent, New

South Waless by 62 per cent and Victorias by zero per cent. So we have grave

concerns about that model and we urge the Senate committee to seriously review

its application.[25]

2.27

Victoria Legal Aid provided the Committee with a

version of the Rush/Walker model with the following amendments (see Table 1.1):

-

removal of the suppression and cost per case risk

factors for 2003/04 funding;

-

inclusion of 2001 Census Data for all states and

territories in the relevant demographic field - state and territory populations

by sex and age, non-English speaking background persons aged 10 and over and

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons aged 10 and over;

-

inclusion of new data for divorces involving

children aged under 18 years for the 2001 calendar year; and

-

inclusion of new data for the proportion of

households earning less than $300 per week.[26]

Table 1.1 Original Rush-Walker funding model compared to 'updated' model

for 2002-03 and 2003-04

|

Distribution of Commonwealth

Funding

|

Calculated Distribution of

Commonwealth Funding

|

|

for the two years to 30 June 2004 based on the original Rush-Walker funding model

|

for the two years to 30 June 2004 based on the updated Rush-Walker funding model

|

|

State

|

2002-03

|

2003-04

|

State

|

2002-03

|

2003-04

|

|

|

$m

|

%

|

$m

|

%

|

|

$m

|

%

|

$m

|

%*

|

|

NSW

|

38.956

|

32.31%

|

41.574

|

32.87%

|

NSW

|

32.699

|

27.12% (-5.19)

|

34.302

|

27.12% (-5.75)

|

|

Vic

|

27.75

|

23.02%

|

27.75

|

21.94%

|

Vic

|

29.648

|

24.59% (1.57)

|

31.102

|

24.59% (2.65)

|

|

Qld

|

23.709

|

19.66%

|

25.612

|

20.25%

|

Qld

|

24.801

|

20.57% (0.91)

|

26.017

|

20.57% (0.32)

|

|

SA

|

10.351

|

8.59%

|

10.802

|

8.54%

|

SA

|

12.286

|

10.19% (1.6)

|

12.889

|

10.19% (1.65)

|

|

WA

|

10.486

|

8.70%

|

11.232

|

8.88%

|

WA

|

12.684

|

10.52% (1.82)

|

13.306

|

10.52%(1.64)

|

|

Tas

|

3.88

|

3.22%

|

3.934

|

3.11%

|

Tas

|

3.569

|

2.96% (-0.26)

|

3.744

|

2.96% (-0.15)

|

|

ACT

|

3.104

|

2.57%

|

3.137

|

2.48%

|

ACT

|

3.448

|

2.86% (0.29)

|

3.617

|

2.86% (0.38)

|

|

NT

|

2.334

|

1.94%

|

2.441

|

1.93%

|

NT

|

1.435

|

1.19%(-0.75)

|

1.505

|

1.19% (-0.74)

|

|

Total

|

120.57

|

100.00%

|

126.482

|

100.00%

|

Total

|

120.57

|

100.00%

|

126.482

|

100.00%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* Same Percentage

Values used as for 2002-03 Data

|

Source: Victoria Legal Aid, Submission

97B, Attachment 1, p.2.

2.28 If

the model were to be subjected to the changes outlined above, the dramatic

changes in funding that would occur are a considerable reduction of funding to New

South Wales, a reduction in funding to Northern

Territory, and an increase in funding to Victoria.

2.29 However

it was not this model that Victoria Legal Aid put forward as its preferred

model.

The Commonwealth Grants Commission model

2.30 Mr

Parsons on behalf of Victoria Legal Aid suggested

that the current funding model should be replaced with a Commonwealth Grants

Commission model. He pointed out that the Commonwealth Grants Commission had

developed a simple model in conjunction with the Attorney-General's Department

and National Legal Aid.[27]

2.31 Victoria

Legal Aid gave the Committee a copy of this model which is shown below at Table

1.2. The basis for this model is different from the Rush-Walker Model, in that

it does not rely on LAC data, but bases its calculations on Grants Commission

assessment methods and relativity factors relating to (amongst other things)

the relative cost of delivering legal services in each state and territory.[28]

2.32 The

most obvious difference between the current funding model (or even the amended

one provided by Victorian Legal Aid) and this 'Grants Commission' model is the

funding to the Northern Territory and the ACT, which would receive dramatically

less funding under the Grants Commission model.

2.33 Victoria

Legal Aid explained that the Commonwealth has been provided with all the work

that Victoria Legal Aid and National Legal Aid have done in relation to

developing a new model. Mr Parsons

also told the Committee that the Commonwealth had committed to having

discussions with the LACs before the end of 2003, before the new funding

agreements are due to be signed off by the end of the financial year 2003-04.[29]

2.34 Victoria

Legal Aid's criticisms of the model were echoed by the Legal Aid Commission of

New South Wales, who also commented on the fact that the model does not account

for unmet legal need. It also confirmed it had consulted with the Commonwealth

about their concerns with the model:

[W]e are talking with

the Commonwealth, but not so much about the details of the model because, to be

perfectly honest, they are all flawed. The Commonwealth Grants Commission have

done some great work for us, but their work is not definitive either. The real

problem with all of that is: there is no way at the moment you can get an

accurate gauge of legal need; therefore you cannot factor that very important

point into these formulasbecause we simply do not know how to measure legal

need or unmet need at the moment. That is the difficulty.[30]

Table 1.2

A Commonwealth legal aid funding model based on

Commonwealth Grants Commission assessment methods, and application of estimated

state relativities to an illustrative 2002-03 funding pool

|

|

NSW

|

Vic

|

Qld

|

WA

|

SA

|

Tas

|

ACT

|

NT

|

Aust

|

|

General legal aid expenditure component (99.9%)

|

|

2000-01

input costs factor (a)

|

1.01355

|

0.99773

|

0.98285

|

1.00804

|

0.98190

|

0.98243

|

1.01549

|

0.99924

|

1.00000

|

|

Dispersion

factor (b)

|

0.99936

|

0.99525

|

1.00278

|

1.00694

|

0.99755

|

1.00770

|

0.98567

|

1.04242

|

1.00000

|

|

Cross

border factor (c)

|

0.99304

|

1.00000

|

1.00000

|

1.00000

|

1.00000

|

1.00000

|

1.13985

|

1.00000

|

1.00000

|

|

Low

income socio-demographic composition factor (d)

|

0.98405

|

0.97364

|

1.05089

|

0.94433

|

1.13019

|

1.18670

|

0.64655

|

0.85119

|

1.00000

|

|

Component

factor (e)

|

0.99171

|

0.96868

|

1.03775

|

0.96039

|

1.10917

|

1.17710

|

0.73908

|

0.88834

|

1.00000

|

|

Contribution

to relativity (f)

|

0.99072

|

0.96771

|

1.03671

|

0.95943

|

1.10806

|

1.17592

|

0.73834

|

0.88745

|

|

|

Isolation related

expenditure component (0.1%)

|

|

2000-01

isolation factor (g)

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

98.10726

|

1.00000

|

|

Component

factor (h)

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

98.10726

|

1.00000

|

|

Contribution

to relativity (f)

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.00000

|

0.09811

|

|

|

State relativity (i)

|

0.99072

|

0.96771

|

1.03671

|

0.95943

|

1.10806

|

1.17592

|

0.73834

|

0.98556

|

1.00000

|

|

Estimated State funding

($m) (j)

|

40.28

|

29.06

|

23.33

|

11.39

|

10.40

|

3.46

|

1.44

|

1.21

|

120.57

|

2.35 The

Attorney-General's Department confirmed that it is aware of some errors in the

model, and that it has been reviewing the model in consultation with the

Commonwealth Grants Commission and the Legal Aid Commissions:

In addition to the cost

per case factor and the suppression factor there were issues discussed in the

course of the review about whether the model should use actual rather than

projected population statistics. There were issues raised about whether it was

a demand driven model or a need driven model. There were also issues raised

about the use of Commonwealth Grants Commission factors and indices, which I

understand have since been changed. I think there were comments made about the

risk factors that were used in the model at the time. There were also what

might be described as technical criticisms of the methodology that was used, on

a more econometric basis.

we have been

discussing those concerns with the Commonwealth Grants Commission staff in the

course of the review and we have put a number of reworked models back to the

commission for comment along the way.[31]

2.36 Victoria

Legal Aid explained that a serious impediment in finding consensus in

consultations between the Commonwealth and the Legal Aid Commissions is that in

any change to the formula there will be winners and losers:

National Legal Aid will

never reach a unanimous view on a funding distribution model, because a funding

distribution model is always going to involve winners and losers. No-one wants

to go to their board and say, I have just agreed to a model that is going to

reduce the funding of our state legal aid commissionand here is my

resignation. We rely on the Commonwealth to show leadership in this area. We

want them to show leadership by adopting a model based on solid empirical data;

not the smoke and mirrors of the Rush-Walker model of 1999.[32]

2.37 The

Attorney-General's Department told the Committee that it was preparing a report

of the review of the model for the Attorney-General, and that a decision as to

whether the model will be changed is a decision that will be made by

Government.[33]

Committee view

2.38 The

Committee is concerned by evidence that the model the Commonwealth currently

uses to distribute funding between states and territories contains errors and

does not account for unmet legal need.

2.39 The

Attorney-General's Department has confirmed some of the errors pointed out by

the Victorian Department of Justice. A separate issue is the methods or factors

used in the model such as the 'suppressed demand factor' and the 'average case

cost factor'. Both of these factors appear to be arbitrary and without sufficient

foundation.

2.40 The

Committee notes that the Commonwealth Grants Commission has developed a basic

alternative funding model that utilises Commonwealth Grants assessment methods.

Whilst the Committee acknowledges that the Grants Commission model accounts for

the relative costs of delivering legal services in each State and Territory,

the Committee believes that a funding model should account for the levels of

demand and need for legal services in each state and territory. For example,

the Committee is not satisfied that the simple 'Grants Commission Model'

supplied by Victoria Legal Aid sufficiently takes into account the specific

challenges faced in the Northern Territory, particularly amongst Indigenous

Australians. The Committee believes that a new funding model based on the

Grants Commission model would be appropriate if it were adjusted to acknowledge

the special challenges faced by the Northern Territory in providing legal

services and access to justice in light of its high Indigenous population and remoteness.

These issues are discussed further in Chapter 5.

2.41 The

Committee is concerned that the current funding model (as well as the 'Grants

Commission model') does not account for unmet need for legal services. The

Committee notes that the Law and Justice Foundation of NSW is conducting an

assessment of legal need in that State, and commends this. At the time of

writing, Stage 2 of that assessment had just been released, which involved a

quantitative legal needs survey for disadvantaged people in NSW.[34] These issues

are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

2.42 Clearly

the unmet need for legal aid cannot be included in the funding model until an

assessment of unmet need has been made. Assessing the level of unmet need for

legal aid in Australia

is clearly a priority if the Commonwealth is to be able to develop a funding

model that optimises the level of access to justice for all Australians.

2.43 The

Committee notes that the Attorney-General's Department is reviewing the current

funding model in consultation with the LACs. The Committee also notes that the

Government's 2004-05 Budget proposes to increase Commonwealth funding for legal

aid by $52.7 million over four years. The Portfolio Budget Statements 2004-05

for the Attorney-General's portfolio notes that this increase will enable

'redistribution of legal aid funds across jurisdictions to meet demographic

changes'.[35]

2.44 The

Committee supports increasing Commonwealth funding for legal aid, however it is

not clear how 'demographic changes' will be determined, and as a result it is

unclear on what basis the increased funding will be redistributed. The

Committee is concerned that despite an increase in funding, there does not

appear to be provision for an assessment of unmet need in each state and

territory.

2.45 The

Committee believes that a new funding model needs to be developed to ensure

that increases in Commonwealth funding to legal aid are distributed in an

equitable and effective manner. As part of developing a new model, the

Committee recommends that the Government undertake or commission an assessment

of both demand for legal aid services and unmet need in relation to legal aid

(discussed further in Chapter 3).

Recommendation 1

2.46

The Committee recommends that the Government reform the

funding model for legal aid, taking into account concerns raised by legal aid

commissions in the recent review of the model. The Committee is not satisfied

with the justifications that have been offered regarding the 'suppressed demand

factor' and the 'average case cost' factor, and recommends that they be

removed.

Recommendation 2

2.47

The Committee recommends that the Commonwealth

Government develop a new funding model to ensure a more equitable distribution

of funding between the State and Territories. This model should be based on the

work of the Commonwealth Grants Commission model, but with increased funding

for the Northern Territory to account for the special challenges it faces in

light of its high Indigenous population and remoteness.

Application of Priorities and Guidelines

2.48 The

Commonwealth Priorities and Guidelines are set out in the legal aid funding

agreements between the Commonwealth and each state and territory. The

Commonwealths Priorities outline the broad areas which should be given

priority in using Commonwealth funds and are contained in Schedule 2 of the

funding agreements.

2.49 The

Guidelines are the tests that are to be applied by Commissions when assessing

legal aid applicants for Commonwealth related matters. They are contained in

Schedule 3 of the agreements and are made up of four parts. Part 1 contains the

means and merits tests that are to be applied to applicants, and parts 2-4

identify the types of family, criminal and civil matters for which Commonwealth

funds may be granted.

2.50 Various

comments were made in submissions and evidence about the different way that

these priorities and guidelines are implemented in states and territories.

The means test

2.51 The

'means test' set out in the guidelines assesses an applicant's assessable

income and assets. Applicants must qualify on both aspects, but if either is

exceeded, a grant may be made if the applicant makes a contribution.[36]

2.52 There

are two types of means test that can be used in assessing applicants for legal

aid. These are the National Legal Aid Means Test and the Simplified Legal Aid

Means Test. The two tests have the same assets test component, but assess

income in a different way. The Simplified Legal Aid Means Test varies from the

National Legal Aid Means Test in that it uses a formula that takes into account

the number of dependant persons in the applicant's household as well as the

employment status of the applicant and partner (if applicable).[37]

2.53 Currently,

all LACs except Queensland and Tasmania

use the National Means Test. The Attorney-General's Department noted that the

Commonwealth preferred the use of the Simplified Means Test because it

considers it easier to administer than the National Means Test, and therefore

more cost efficient.[38]

The Committee did not receive evidence from the LACs on the two tests.

2.54 In

relation to the means test, National Legal Aid argued that many people who

presently do not qualify for legal aid are unable to afford the services of

private lawyers to conduct their cases, or are unable do so without undue

hardship.[39]

2.55 National

Legal Aid argued that Commonwealth funding should be increased to allow the

means test to be adjusted to improve access to legal aid for those unable to

afford private representation.[40] It also noted that it had recently commissioned

research by Griffith University which indicated that there was a relationship

between the level at which the means test was set and self-representation in

the Family Court: It would not be unreasonable to speculate that the

situations identified in this research are likely to be paralleled in other

areas of the law.[41]

2.56 A

submission from Professor Rosemary

Hunter and Associate

Professor Jeff Giddings

of Griffith University,

who conducted the research commissioned by National Legal Aid, noted that their

research showed a significant income difference between those who met the means

test and those who were able to afford private representation.[42] Those

eligible for legal aid earned less than $25,000 p.a. after tax, yet people only

became able to afford private representation once they earned over $45,000 p.a.

after tax. Professor Hunter

and Associate Professor Giddings

noted that those between these income levels may have had financial commitments

that were not taken into account in the income test. They also pointed out that

low income people often met the income test but failed the assets test, despite

not having access to those assets being assessed.[43]

2.57 The

Hon. Justice Alastair Nicholson,

Chief Justice of the Family Court, also referred to this gap:

There is undoubtedly a

gap, if you like, between qualification for legal aid and the ability to fund

your own legal proceedings. Too many people fall into that gap A lot of these

people have no hope of being able to pay for legal expenses, yet the means test

is set at such a level that they are excluded.[44]

2.58 The

Welfare Rights Centre argued that this issue was particularly relevant to low

income defendants in welfare fraud prosecutions, who may have no income other

than welfare, but may own their family home, and hence fail the assets test:

There should be no

regard to the value of their principal home, if the person is on low income. A

classic example is someone [who] is on a disability support pension and all

they have is their principal home, who is charged with an offence in relation

to a $20,000 social security debt. There should be accessible legal aid for

that person, because they are not going to get legal representation anywhere

else. A disability support pension recipient may have an intellectual, psychiatric

disability or a brain injury that may be slightly relevant in that person

having incurred the debt in the first place and also highly relevant in them

not having chosen to access admin review of the debt before it got to that

point.[45]

2.59

The

Welfare Rights Centre explained that in NSW a person's equity in his or her own

home is disregarded up to $195,200. In non-criminal matters the Commission is

given the discretion to disregard a person's home equity, however for criminal

matters there is no such discretion.[46] The Welfare

Rights Centre argued that for criminal matters the means test for low income

earners or those on social security should be disregarded and for non-criminal

matters the threshold at which home value is considered should be raised

significantly.[47]

2.60 Professor

Hunter and Associate

Professor Giddings submitted that their

research suggests a correlation between the application of the means test

(particularly the assets test) and increasing levels of self-representation.[48] They

suggested three reforms to the means test which they argue would reduce the

levels of self representation in the Family Court:

These are:

1. take into account the question of

whether the litigant has realistic access to assessable assets

2. take into account previous attempts

to pay for private legal representation and existing debts to previous legal

representatives

3. extend eligibility to include a

higher proportion of clients earning less than $30,000 after tax.[49]

2.61 However,

if the means tests used by the LACs were modified in such a way without

increasing funding, it may simply lead to a more stringent application of the

merits test, as the Northern Territory Legal Aid Commission noted:

Without a substantial increase in funding, the NTLAC is unable

to increase the means test to enable more people to qualify for legal aid. If

the means test limits were to be increased on existing funding, the NTLAC would

have no choice but to read the merits test more narrowly to exclude enough

applicants for the NTLAC to remain within budget. The number of

self-represented litigants would therefore not be reduced but would simply be

caused by other reasons.[50]

The merits test

2.62 The

'merits test' essentially comprises three elements:

-

a legal and factual merits test;

-

a prudent self funding litigant test; and

-

an appropriateness of spending limited public

funds test.[51]

2.63 The

legal and factual merits test looks at whether the applicant has a reasonable

prospect of success. The prudent self funding litigant test is met if the

Commission considers that a prudent self funding litigant would risk their own

funds in the proceedings. The final element of the test is whether the

Commission considers the costs involved are warranted by the likely benefit to

the applicant or the community.[52]

2.64 The

Committee heard various arguments that the elements of the merits test are

substantially subjective. The Legal Aid Commission of NSW argued that the

'prudent self funding litigant' test should be abolished, on the grounds that

it is subjective, ambiguous, and difficult to apply in a transparent manner.[53]

2.65 The

difficulty in applying such a subjective test was echoed by the Combined

Community Legal Centres Group of NSW (CCLCG). In regards to the 'prudent self

funding litigant' test, Mr Simon

Moran explained:

Your guess is as good

as mine as to what that means. We have ideas and ways of addressing the

commission which we feel deal with that. Then there is this kind of catch-all

test at the end, which is whether the case is an appropriate spending of

limited public legal aid funds. Again, this leads to a sense of arbitrariness

with the provision of legal aid, which does not assist clients or,

particularly, solicitors when they are considering acting on a legal aid basis.

That has led to an increase of those issues regarding eligibility. We have

sensed their increase over the last five to seven years, and that has had an

impact on community legal centres as well as other legal service providers.[54]

2.66 There

were also concerns raised regarding the 'appropriateness of spending limited

public funds test'. The CCLCG gave an example to illustrate the subjective or

discretionary nature of the test:

The [case was] a

disability discrimination case that was brought by a man who had a disability

and who could only have accessed the town centre using his wheelchair. He could

not access the town centre as a result of various problems with footpaths, with

paving and with access on and off buses. So he considered bringing a complaint

of disability discrimination against the town council on the basis that he

could not access the premisesthe premises being the footpaths. We applied for

legal aid there. Essentially Legal Aid said, Its going to cost too much to

run; we cant fund this case, even though that person fitted into the means

test and there were reasonable prospects of success.[55]

2.67 There

was concern that the merits test is applied in different ways between states

and territories.[56]

Quoting research by Griffith University,[57] National

Legal Aid stated in its submission:

Amongst our concerns has been parity of eligibility across LACs.

In this regard the report which states There were evident differences between

Registries in both relative success rates in legal aid applications, and the

reasons why applications were unsuccessful. These differences appear to reflect

the respective family law funding positions of the Legal Aid Commissions. In Brisbane,

where demand for family law legal aid funding considerably exceeds the

available supply, applicants were more likely to be unsuccessful, and

applications were more likely to be rejected on the basis of merits. In Melbourne,

where the reverse situation applies, applicants were more likely to be wholly

successful, and the applications were more likely to be rejected on the basis

of means. In Canberra, and Perth,

which fall somewhere in between, applications are more likely to be

successful.[58]

2.68 Legal

Aid Queensland confirmed that the

different application of the guidelines was due to different levels of

available funds in each commission:

Legal Aid Queensland

applies the merit test with great rigour and reads it more expansively than do

other legal aid commissions. This is due to the funding shortfall requiring

funding constraints in the granting of legal aid for family law applications.[59]

Committee view

2.69 The

Committee's Third Report noted that

under the National Means Test the various jurisdictions were allowed to set

different monetary limits to items allowed under the test. The Committee noted

that this was to cater for both inter and intra-jurisdictional differences in

economic conditions. Whilst the Committee noted that it did not oppose such

variations in the means test levels if they were necessary in order to achieve

equitable outcomes in the light of differing economic conditions, the Committee

opposed such variations if based on inadequate provision of legal aid funds by

governments.[60]

2.70 The

Committee recommended that the Commonwealth Government ensure that the means

test income and asset levels were set at the same amounts for all parts of Australia,

unless regional variations could be shown to be justified by differing economic

conditions. The Committee also recommended that the Government conduct a review

of the appropriateness of the means test levels that currently apply.[61]

2.71 The

Government responded that it was unaware of any evidence that the legal aid

commissions tighten the means test to limit eligible applications for

assistance, and as a result it did not consider a review of the means tests was

necessary. It also noted that the Commonwealth preferred the use of the

Simplified Means Test.[62]

2.72 Regardless

of whether legal aid commissions are using the means or merits test in order to

limit applications by otherwise eligible applicants for budgetary reasons, the

Committee is genuinely concerned by evidence that there is a considerable gap

between those who qualify for assistance, and those who are able to afford

private representation.

2.73 The

Committee acknowledges that in many states, particularly New

South Wales, the means test appears to place a large

obstacle for many home owners. The Committee is concerned by evidence given by

the Welfare Rights Centre that many of its clients, particularly those with

intellectual disabilities, are stopped from accessing legal aid due to their

levels of home equity, despite having a very low income or being reliant on

social security.

2.74 The

Committee is also concerned by comments from Professors Hunter and Giddings, as

well as the Chief Justice of the Family Court, that there is a considerable gap

between those eligible to receive legal aid, and those who are actually able to

afford private representation.

2.75 However,

the Committee is also aware that if the means tests are made too liberal, then

Commissions may simply be forced to rely on arbitrary application of the merits

test in order to distribute limited resources.

2.76 The

Committee acknowledges the recommendations made by the Welfare Rights Centre

and Professors Hunter and Giddings. The

Committee believes that LACs should conduct an assessment of current

applications, and consider what the increase in successful applications would

be if those recommendations were implemented. This is necessary to be able to

assess the increase in demand these changes would place on current legal aid

resources.

Recommendation 3

2.77

The Committee recommends that the state and territory

legal aid commissions conduct an assessment of current applications, to

ascertain what increase in successful applications would occur if the following

changes were made to the merits test:

(a)

extend

eligibility to those earning less than $30,000 after tax; and

(b)

in criminal

matters, where a person passes the income test, disregard

home

equity.

Breakdown of funding by type of matter: criminal, family and civil

2.78 The

Committee's Third Report noted that

there had been concern that the Commonwealth Guidelines may cause criminal

matters to be funded at the expense of family matters, and that both criminal

and family matters may be funded at the expense of civil matters.[63] However the

Committee noted that there was no support for a strict hierarchy in the

Guidelines to ensure a particular distribution across the various types of

matters, as the result may be that the system is too rigid.[64]

2.79 The

Committee heard arguments that the funding priorities and guidelines favour criminal

matters over family law matters (see further in Chapter 4). The Committee also

heard that there are serious deficiencies in the level of legal aid available

for civil matters as a result of the Commonwealth funding guidelines.

2.80 The

Victorian Department of Justice explained that following the Commonwealth

funding cuts and the introduction of the Commonwealth Priorities and Guidelines

in 1997, funding for civil matters was almost abolished:

The impact for Victoria was severe. It included the almost complete

abolition of legal aid for civil matters so that now grants of legal aid are

very rarely made for matters such as discrimination, consumer protection,

tenancy law, social security law, contract law and personal injuries. Some of

those matters have been picked up by the private profession on a no win, no

fee basis, but substantial areas of law, particularly poverty related law,

have not been picked up.[65]

2.81 A

similar assessment was provided by the Legal Services Commission of South

Australia:

There are major gaps in

legal service available to the South Australian community. No legal

representation is funded for any civil disputationfor example, householders

versus builders, car dealers and insurance companies.[66]

2.82 Ms

Zoe Rathus on

behalf of the National Network of Women's Legal Services (NNWLS) also noted

that funding to civil matters had resulted in a drought of services:

I want to start by

reminding the committee of the number of areas of law that are simply not

covered anymore by legal aid and the concern amongst community legal centres

generally that there are areas of law where people can say, Theres no legal

aid for that. There seems to be a full stop, particularly in areas such as

immigration law and large areas of civil law for which legal aid is simply not

available anymore. We do not consider it acceptable for those kinds of areas to

exist.[67]

2.83 Whilst

the news from LACs was bleak in relation to the effect of the Commonwealth

Guidelines on assistance in civil matters, there was praise for the way that

NSW Legal Aid was providing assistance in civil matters:

The Legal Aid

Commission of New South Wales has a very innovative, very highly skilled

inhouse civil law program. Our experience as community legal centres is that

they are very highly skilled. They are very good at their job, and they have

specialist skills that other solicitors do not have. I believe that is the only

in-house civil unit in Australia, and it has been shown in New South Wales to be very valuable. I think other

commissions throughout Australia would be wise to adopt a similar model.[68]

2.84 Despite

the effectiveness of the civil unit administered by NSW Legal Aid, the

Committee heard that there is still substantial unserviced demand for civil

assistance in NSW, particularly in regional areas:

We see clients who have

problems with civil law, although New South Wales is one of the better states in its civil

law funding. We find that there is a huge demand for legal assistance in

employment law, particularly in the Blue Mountains, which is a tourist area and has a lot of parttime work and employment

of young people in under award situations. We are finding that, with that, a

deunionised work force and an increase in Australian workplace agreements, we

are getting a lot of demand in the complex area of employment law. Our region

needs either our centre or Legal Aid to fund an employment lawyer and possibly

a discrimination lawyer as well.[69]

2.85 The

Committee heard that Commonwealth funding for representation in Administrative

Appeals Tribunal (AAT) matters is limited to certain areas. The Committee also

heard that without free assistance in the non-cost jurisdictions of the AAT,

many people will not proceed, as the costs will often outweigh the award. The

Law Council of Australia explained that in the non-cost jurisdiction of the

AAT, up to a third of people are unrepresented:

that is a lot of

people. It is important to those people because they are often disputing

employment problems or welfare problems and so on. [70]

2.86

The Law

Council of Australia argued that the solution, apart from increasing funding,

is to relax the guidelines in relation to civil matters. [71]

2.87

Westside

Community Lawyers suggested that another way to remedy the lack of legal aid

for assistance and representation in civil matters was to provide duty

solicitors for such matters and noted that a pilot study into such a service was being conducted with final

year university students in the Adelaide civil registry.[72]

Committee view

2.88

The

Committee is concerned that the Commonwealth Priorities and Guidelines deny

adequate assistance in family and civil matters.

2.89

Whilst

the Committee acknowledges the importance of representation in criminal

matters, the Committee believes that adequate funding should be provided to

legal aid such that less restrictive guidelines may be introduced.

2.90

The

Committee is particularly concerned that adequate legal aid is not available to

those appearing before the Commonwealth AAT, as a substantial proportion of

such matters involve important issues such as employment and discrimination.

2.91

The

Committee believes that a duty solicitor service should be available for the

AAT.

Recommendation 4

2.92 The Committee recommends that the

Commonwealth introduce a duty solicitor service for the Commonwealth

Administrative Appeals Tribunal.

Specialist legal services

2.93 One

way to ensure that traditionally neglected types of matters receive a minimum

level of service is through the funding of specialist legal services. The

Committee received evidence in relation to the Commonwealth funding of two particular

services:

-

the Environmental Defenders Offices; and

-

an argument that the Commonwealth should create

and fund a forensic science institute to provide services to defendants.

Environmental Defenders Office

2.94 The

Environmental Defenders Office (EDO) was established to ensure there were legal

services representing public interest environmental law. The EDO

ensures that where a member of the public seeks to advocate an issue that is of

environmental public interest (and as a result may be unable or not prepared to

fund it themselves) the matter is accorded the necessary legal services.

2.95 In

terms of Commonwealth funding, the EDOs are restricted from using their funding

for litigation purposes. The Committee heard in its last inquiry that this

restriction imposed a significant constraint on the EDO

advocating to its full potential, and the Committee recommended that this

restriction by the Commonwealth be removed.[73] Mr

Mark Parnell

on behalf of the EDO explained to the Committee the

impact this restriction on Commonwealth funding had on them, and why it should

be removed:

To a certain extent,

this inquiry today has an element of deja vu about it. It has very similar

terms of reference to those of the inquiry back in 1997 and 1998, when the

Senate last looked at this, and I am saying very similar things to what a

colleague of mine said at that inquiry. We raised the issue of the litigation

restriction. We made the point that it had no basis in policy and that it was

politically motivated, and the Senate committee at that stage recommended that

that condition be removed.

The only policy grounds for not letting us litigate with legal aid money

seems to be the inherently political nature of environmental law. We are very

often challenging the decisions of the executive. We are challenging decisions

of statutory authorities and of ministers. We are challenging them on the

merits and on legality. The view seems to be that public funds should not be

used to challenge those sorts of decisions. The argument that I would put is

that that is like saying that we should not publicly fund criminal defence work

because it simply suggests that our law enforcement officers do not get it

right sometimes and that there should be no public funds used for defence. It

is exactly the same in relation to environmental law.[74]

2.96

Fitzroy

Legal Service also argued that the litigation restriction that is placed on the

Environmental Defenders Office should be removed.[75]

Commonwealth

funding for a forensic science institute

2.97

Liberty Victoria advocated the need for the Commonwealth to

establish an independent forensic science institute to assist in the defence of

those defendants who are facing charges supported by forensic evidence. Their

argument was that a lack of resources means that many defendants are unable to

afford the necessary defence to face charges that are supported by forensic

evidence.

Our principal concern

is that the field is heavily weighted against accused persons because they

simply do not have access to either the scientific or legal resources to enable

them to be, in a sense, playing on an even field. It is Libertys submission that, very rapidly, steps need

to be taken to correct this situation.

Liberty Victoria submits that it is necessary for a discrete institute to be established

for the use of accused persons and that, being a scientific institute, it

should have resources somewhat equivalent to those now available to the

prosecution authorities. At the present time, if accused persons wish to

challenge the scientific evidence relied upon by the prosecution, they have to

go looking in appeal to see if they can find qualified experts who are not

associated with the prosecution. That is very difficult. As DNA evidence in

particular becomes increasingly relied upon by the prosecution, that is going

to become an even more significant problem for accused persons.[76]

2.98

Liberty Victoria proposed that if such an institute were created, it would be able to

attend major crime scenes and offer an effective check to ensure that forensic

evidence is collected and processed in a proper manner.[77]

Committee view

2.99

The

Committee believes that although criminal matters appear to be funded at the

expense of family matters and that both criminal and family matters are funded

at the expense of civil matters, the Commonwealth Priorities and Guidelines

should not be amended to mandate a particular distribution of funding between

types of matter.

2.100

The

Committee reiterates the point it made in the Third Report that whilst attention must be paid to how funds are

distributed between matters, it would not be of benefit to have a rigid or

inflexible set of priorities for the purposes of funding allocation.

2.101

The

Committee was disappointed to hear that the EDO is still facing operational difficulties

because of contractual restrictions in its funding agreement with the

Commonwealth. The rationale for having a Commonwealth funded EDO is to ensure

that the area of public interest environmental law, which would otherwise have

little priority for receiving legal aid, is effectively advocated. For the EDO to be able to effectively advocate, it

needs to have the freedom to choose how it uses its funding in relation to

litigation.

2.102

The

Committee repeats its recommendation that the Commonwealth remove the

restriction on the EDO from using Commonwealth funding for

litigation purposes.

Recommendation 5

2.103 The Committee recommends that the

Commonwealth remove the restriction on the Environmental Defenders Office from

using Commonwealth funds for litigation purposes.

2.104 The Committee was

interested in the suggestion by Liberty Victoria that a national

institute for forensic science be established to ensure defendants have equal

access to such science as the prosecution does. Consequently the Committee considers that the

Government should support the establishment of such an institute.

2.105

The

Committee notes, however, that whilst it supports the idea in principle, it

does not believe the funding of such an institute should be done at the expense

of further funding to legal aid generally.

Recommendation 6

2.106 The Committee recommends that the Government

fund the establishment of a national forensics institute to provide forensic

opinions for defendants in serious criminal matters facing forensic evidence.

'Law and order' legislation and

increased demand for legal aid

2.107

The

Committee heard from LACs that when state governments engage in 'law and order'

campaigns, and introduce corresponding legislation, there is an increase in

demand for legal aid.

2.108

The

Legal Services Commission of South Australia explained in evidence that the

recent law and order campaign in that state, which manifested itself in the

form of stricter criminal trespass legislation, has lead to a steady increase

in demand for legal aid.

Our hypothesis is that

as the law and order campaign takes effect and new legislation is brought in

for serious criminal trespass, which has elevated the penalties imposed by the

courts on people trespassing on peoples property when they are present the

number of matters going to the district court has increased significantly, they

are being contested hard and, because the emphasis is on longer sentencing, the

sentencing submissions are being fought much harder. Our statistics have borne

that out. We are getting the Office of Crime Statistics and Research to

validate the research we have done. At the rate we are going, we have had to

ask the government for $1 million more in the next financial year just to

maintain the rate at which we are currently expending funds in the criminal

jurisdiction.[78]

2.109

This view

was supported by Victoria Legal Aid. Mr Tony Parsons noted that as a result of a road safety campaign there has been an

increase of applications for legal aid for road safety matters that involve the

risk of prison. These have included third offences, driving over the legal

limit (0.05) and dangerous driving. He noted that Victoria Legal Aid had been

fiscally compensated for this impact by the Victorian Government.[79]

2.110

Victoria

Legal Aid was asked in evidence for its views on a 'legal aid impact statement'

when legislation is introduced. Mr Parsons supported the idea:

It is a very sensible

proposal. Obviously legislation can have ripple effects and it is very

important that those ripple effects be taken into account so that the needs can

be best met.[80]

2.111

The Committee

asked Victoria Legal Aid whether the Commonwealth had undertaken such an

assessment or consultation with LACs. Mr Parsons noted that Commonwealth legislation has had an impact on legal aid

demand, and gave the specific examples of changes to the Family Law Act, social

security provisions and changes to the migration law.[81] He noted that

LACs are generally well consulted by the Commonwealth on reviews of legislation

and have the opportunity to respond to proposed legislative programs. Despite

such consultations, when a legislative program does proceed, there is no

corresponding compensation given by the Commonwealth, even where an impact on

legal aid demand is identified.[82]

Committee view

2.112

The

Committee believes that state and territory governments should pay specific

attention to the impact on legal aid demand when developing proposed

legislation. This consideration could either be in the form of including a

'legal aid impact statement' in the explanatory memorandum to legislation, or

through consultations with LACs.

2.113

However,

the Committee notes Victoria Legal Aid's comments that although the

Commonwealth consults over such proposed legislation, there is no corresponding

compensation when an increase in demand for legal aid services is identified.

2.114

The Committee

believes that state and territory and the Commonwealth Government must take

responsibility for increases in demand for legal aid that result from its new

legislation, and provide supplementary funding for LACs accordingly.

Recommendation 7

2.115 The Committee recommends that Commonwealth

and state/territory governments should provide legal aid impact statements when

introducing legislation that is likely to have an effect on legal aid

resources.

Recommendation 8

2.116 The Committee recommends that Commonwealth

and state and territory governments engage in consultations with legal aid

commissions when introducing legislation that may increase demand for legal

aid. If such an increase is identified, governments should provide

corresponding increases in funding to compensate legal aid commissions for this

increase in demand.

The Commonwealth/State dichotomy

2.117 There

was substantial 'in-principle' opposition to the Commonwealth/State funding

dichotomy. In addition to the in-principle opposition, there were criticisms

that the separation increased administration costs and resulted in an

inefficient use of what funding was available for Commonwealth matters.

In-principle opposition

2.118 The

Committee heard argument that the insistence of the Commonwealth that

Commonwealth funds only be used for matters arising under Commonwealth laws was

inefficient, and resulted in the Commonwealth failing to meet its obligations

to those for whom it has special responsibility.[83]

2.119 The

Law Institute of Victoria argued strongly against the dichotomy:

The rule that

Commonwealth funds may only be applied to Commonwealth matters is illogical and

arbitrary in its operation. It is this rule that has resulted in the legal aid

system failing so abjectly to meet the needs of the very people that it is supposed

to serve. We adopt the position that this rule should be abolished and that VLA

[Victoria Legal Aid] should be allowed to allocate legal aid funding according

to need. It should be left to VLA to determine where the interests of justice

require that legal aid be made available. Distinctions between Federal and

State laws are historical anomalies that are meaningless for present purposes.

The cynical adoption of this arbitrary distinction operates to diminish the

standing of the administration of justice in the eyes of those who come into

contact with it. To adopt these distinctions as a basis for withholding funding

encourages obfuscation of the issues by allowing the Federal and State

governments to shift responsibility for the gaps in the legal aid system.[84]

2.120

There

was a strong opposition to the dichotomy in submissions,[85] with no

submissions supporting it.

Administration costs

2.121 Because

the funding agreements first introduced in 1997 require that the LACs only use

Commonwealth funds on matters arising under Commonwealth laws, the LACs are

effectively required to maintain two sets of books.

2.122 Victorian

Legal Aid explained that under the funding agreement they are permitted to, and

do, spend five per cent of the Commonwealth allocation on administering the Commonwealth

Priorities and Guidelines.

The Commonwealth

permits VLA to take five per cent of the annual Commonwealth funding to

administer the Commonwealths program in this state. We have provided them with

financial data that indicates that that is about what it costs us to administer

the Commonwealth program. A substantial part of that five per cent is having to

effectively run two sets of books.[86]

2.123

The

substantial administration costs that are created by maintaining separate

accounts for funding was reinforced by the Legal Aid Commission of New South

Wales, which explained they spend 4.5 per cent of their Commonwealth funding on

administration.[87]

Inefficient use of Commonwealth funds

2.124 There

was criticism that the restrictions imposed by the guidelines stopped

commissions from using funds in matters that should rightly receive

Commonwealth funding. The Legal Aid Commission of NSW argued that the

restrictions imposed by the guidelines preclude those without dependant

children from accessing aid in a property dispute. Furthermore the requirement

that the applicant's equity in the matrimonial home be less than $100,000

precludes the vast majority of those in NSW from accessing legal aid:

The range of family law areas, which LACNSW is permitted to

undertake, is limited. Whilst it can

undertake work in child-related matters including residence and contact, child

support and certain maintenance areas, it is severely restricted in the types

of property dispute matters it can undertake.

For example, Guideline 8.2 states that legal assistance for

property matters may only be granted if the Commission has decided that it is

appropriate for assistance to be granted for other family law matters. The guidelines further state that legal

assistance should not be granted if the only other matter is spouse

maintenance, unless there is also a domestic violence issue involved.

This guideline effectively precludes people who have not had

children or whose children are adult, from obtaining a grant of aid. It also indirectly precludes aid for older

people. This guideline is discriminatory

and could be unlawfully so. If the

guideline is changed as it should be, further funding will be required to support

the likely increase in the number of cases which present.

Another problem is that legal aid may only be granted in certain

property disputes where the applicants equity in the matrimonial property is

valued at less than $100,000. Given real

estate values in NSW, the effect of this restriction is to deprive many people

who would otherwise be deserving of assistance.[88]

2.125 There

was also criticism that Commonwealth funds were being applied inconsistently

between each state and territory. The Victorian Department of Justice explained

that as different Commissions apply the guidelines differently, and some engage

in debt recovery processes that others do not, some LACs have scarce

Commonwealth funds available whilst some have a surplus they are unable to use:

The fact of the matter

is that, in the course of the last five years, we have built up a $20

million-odd reserve of Commonwealth funds. I want to spend that money. You

could never say that Legal Aid is meeting unmet legal need in the state of Victoria. The fact that the Commonwealth micromanage

how we can spend their money means that we struggle to do that; we struggle to

spend the money that we efficiently and rigorously collect from the community

who can afford to repay it.[89]

2.126 Victoria

Legal Aid explained that they regularly approach the Commonwealth for

permission to use this surplus for matters that are arguably of Commonwealth

responsibility, and are denied. When asked what the Commonwealth agreement said

on the issue, Mr Parsons

responded:

That money is collected

from clients who previously were given legal aid in Commonwealth law matters.

So the money we have collected is identified as a Commonwealth asset in our

bank account but the Commonwealth funding agreement says that we can only spend

Commonwealth revenue on a limited range of Commonwealth law legal aid matters;

that is, family law involving children and a very limited range of other

mattersfor example, veterans affairs.[90]

2.127

When

asked whether Victoria Legal Aid had sought permission to spend this surplus,

he responded that they had 'constantly and regularly' and were always refused.[91]

2.128 The

South Australian Legal Aid Commission proposed a compromise which would allow a

more flexible and efficient use of Commonwealth funds. It proposed that the

Commonwealth allow legal aid commissions to use 5-10 per cent of funding for

state matters.[92]

This would stand as a compromise, as the Commonwealth's desire to retain

Commonwealth funding for Commonwealth matters would be retained, but

Commissions would have the flexibility of using 5-10 per cent of funding for

matters that may exist in the grey area of the guidelines or may be of

particular need.

Committee view

2.129 The

Committee believes that the Commonwealth/State funding dichotomy is arbitrary

as many legal matters do not fall neatly in either category. Making such an

arbitrary distinction not only inhibits the effective servicing of legal needs,

it creates unnecessary administration costs for legal aid commissions. The

Committee is concerned by evidence from commissions that between 4 per cent and

5 per cent of Commonwealth funding is spent in administration costs. Clearly

the overall administration costs for Commissions would be reduced if they were

not required to maintain two separate accounts for funding.

2.130 The

Committee is also concerned by evidence from Victoria Legal Aid that it has a surplus

of Commonwealth funds, but is unable to use it on cases that may not fall

clearly within the Commonwealth Guidelines.

2.131 The

Committee believes that the Commonwealth/State funding dichotomy (ie the

'purchaser/provider' model) should be abolished, and funding should be returned

to the co-operative funding arrangements that were in place prior to the

creation of the dichotomy.

2.132 However,

if the current funding arrangements are retained, the Committee supports the

recommendation by the Legal Services Commission of South Australia that Legal

Aid Commissions be given a discretion of 10 per cent of Commonwealth funding,

to be used at the discretion of the LACs. This would allow them some

flexibility in accounting for demands for service that may not fall clearly

within the Commonwealth guidelines, but should rightly be serviced by

Commonwealth funds.

Recommendation 9

2.133

The Committee recommends that the current

purchaser/provider funding arrangement be abolished, and that Commonwealth

funding be provided in the same 'co-operative' manner as existed prior to 1997.

Recommendation 10

2.134

If the current purchaser/provider funding arrangement

is retained, the Committee recommends that the Commonwealth Government amend

the funding agreements to allow the legal aid commissions to use 10 per cent of

Commonwealth funding at their own discretion.