Chapter 6

Infrastructure

6.1

Infrastructure is a means for the delivery of goods and services that

promote prosperity, growth and wellbeing. Infrastructure is an essential input

to virtually all economic activities. Ensuring that infrastructure is adequate,

allocated to the right areas and used effectively reduces economic costs and

contributes to more efficient production.

6.2

Australia is particularly dependent on efficient infrastructure and

investment due to its size and population dispersion (road, rail, airports and

communications), its climate (water and electricity) and its reliance on trade

(ports).

6.3

In 2005, the Productivity Commission estimated that infrastructure

sector reforms up to 2005 had increased Australia’s GDP by 2.5 per cent.[1]

Again in 2005, the Export and Infrastructure Taskforce, chaired by Dr Brian Fisher,

reported that there were immediate export infrastructure constraints caused by Australia's

role in supplying the global commodities boom, but that these were localised in

nature.[2]

6.4

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2006 Economic

Survey of Australia found that infrastructure market reforms undertaken

under the National Competition Policy were largely a success. However, the OECD

emphasised that there remains 'unfinished business' to raise productivity and

reduce bottlenecks in all sectors, but most pressingly in water markets, where

little progress has been made to date.[3]

6.5

This chapter examines the current state of infrastructure, and the

factors which have impacted on the effectiveness and efficiency of significant

recent investment by the states in infrastructure development. It then examines

the role of Public-Private Partnerships and of the Commonwealth in

infrastructure provision and development.

The current state of infrastructure

6.6

The adequacy and serviceability of the existing infrastructure pool was

commented on by a number of witnesses, who in general took the view that

infrastructure development, as well as maintenance of the existing pool, had

lagged. Treasury officials submitted that the average age of Australia's public

sector infrastructure has been rising since the 1970s.[4]

The committee notes that the average age of that infrastructure is now

approximately 20 years,[5]

and that Australia's infrastructure lags behind the average of leading advanced

economies in terms of its ability to support economic activity.[6]

6.7

Dr Vince FitzGerald, observed that across the country, underinvestment

by state governments in critical infrastructure has led to economic capacity

constraints:

...we were underinvesting in infrastructure and we are paying for

that now. We have rising congestion on our roads; we have increasing congestion

in even the public transport system; we have a backlog of facilities, and not

simply current services, in health; and so on... [I]n my opinion, we are

playing catch-up, as is the nation generally. We have got stresses and strains

in the export infrastructure...[B]ulk export infrastructure is the most obvious

area that we see occasionally highlighted in the media, but it is also right in

the metropolitan regions of Australia, whether you are talking about Brisbane,

Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, Adelaide or perhaps Hobart—certainly in the bigger

cities. In today’s service economy era, when the transport of goods and people

around those regions is what makes the economy go, we clearly have backlogs.

Having strong infrastructure investment programs is overdue, frankly.[7]

6.8

Dr Steve Thomas MLA, Shadow Treasurer in Western Australia, pointed out

the shortcomings in infrastructure in key economic locations such as Karratha:

The hospital struggles and transport issues are significant. The

era of opportunity for Western Australia might pass us by without us being able

to put the infrastructure in place that would develop those resources well into

the future.

...

Most of the iron ore royalties go to the state. The state

government has to some degree dropped the ball on this over time. Oakajee, for example,

which is just north of Geraldton and will be the mid-west iron ore port - a

brand-new port which will be developed and built by the private sector - was

first mooted a decade ago.[8]

6.9

Mr Terry Mills MLA, Opposition Leader in the Northern Territory,

commented that:

Although there has been an increase in infrastructure spending in

recent years, much of this spending has been aimed at repairing an ageing asset

base...[M]uch of the infrastructure is reaching its use by date....Many roads,

schools, hospitals and other assets now need work. There will be a need to

borrow substantially for infrastructure augmentation into the future.[9]

6.10

Mr Kim Wells MP, Shadow Treasurer in Victoria, presented a range of

statistics to the committee showing that hospitals, schools and water

infrastructure in Victoria were attracting insufficient investment. In relation

to water, Mr Wells submitted that:

I think the Melbourne water authorities deliver a good service;

the reality is that there is not the infrastructure to support them. We have

pipelines that are crumbling. We have lack of infrastructure. If the infrastructure

were in place, like the [desalination] plant, it would assist the water

authorities. But we are not seeing that at the moment. There are lots of

promises and plans, but we will wait and see what occurs over the next couple

of years.

...

I think water authorities should pay a dividend, but I also

think that some common sense should be applied. If your infrastructure is

crumbling around you, you should be able to say to the water authorities, 'That

dividend will be reviewed or suspended,' to allow the water authority to use

retained earnings to build that infrastructure.[10]

6.11

Mr Wells also submitted that major road funding had been neglected by

the Victorian Government, and that this had resulted in economic losses:

We have spent less per head on construction than any of the

other states has. Obviously, you would expect Western Australia and Queensland

to spend more than us, but in Victoria we do not seem to spend the money on

roads, bridges or tunnels. We do not build things or fix things. As a result...

for anyone travelling on Melbourne roads—the Calder, the Monash or the

eastern—there is gridlock. It is costing us and our economy millions and

millions of dollars because we are having trouble moving our products and our

personnel around... on our main roads, in the morning peak, traffic travels at

around 20 kilometres per hour and, in the afternoon peak, we travel at around

35 to 40 kilometres per hour.[11]

6.12

Dr Bruce Flegg submitted that the Queensland Government under Premiers

Beattie and Bligh had not completed one major road project since 1998, and was

trying to build infrastructure at the top of the economic cycle when it was

most expensive.[12]

This was a theme running through the evidence of a number of witnesses, some of

which is discussed later in this chapter.

6.13

Recent increases in infrastructure spending by the states and territories

followed a prolonged period in which they placed very low priority on

infrastructure investment. Treasury submitted that state net capital investment

in the total public sector has more than doubled in recent years, rising from

around $11 billion in 2005–06 to $23 billion in 2007–08. It is projected

to peak at $32 billion in 2008–09 and then moderate to around $24.5 billion in

2010–11.[13]

Strategic management of infrastructure development

6.14

The need to invest in infrastructure has not been lost on states and

territories, and one reason for the deterioration in their fiscal position in

recent years has been their sharp increase in infrastructure investment. This

section examines the factors that have affected the success of state and

territory investment in infrastructure over recent years, and the impact it has

had on the broader economy.

Timing

6.15

The committee heard that the recent surge in infrastructure spending by

the states and territories is symptomatic of a general pattern of not

anticipating and responding in a timely and effective way to infrastructure

needs. Rather, infrastructure problems were allowed to reach breaking point

before corrective action was taken.[14]

6.16

Due to State Government inactivity in recent years, there is an urgent

need for investment in infrastructure, much of which should be provided by the

private sector. However, increased infrastructure spending by states and

territories at a time when unemployment was very low, and demand for skilled

labour strong, strengthened inflationary pressures in the economy and, in all

likelihood, crowded out worthwhile private sector investment. This impact was

not lost on Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Glenn Stevens, who was quoted by

Treasury officials as saying that:

Ideally [the investment] would have been done five years ago

when the miners did not want to do it at the same time, but it was not. It

still has to be done and, yes, that is a factor at work in the economy along

with very strong private demand and along with...large foreign stimuli... So

there are a lot of things that are basically giving us quite a strong demand

picture. Those infrastructure spend things are one, but only one among a

number.[15]

6.17

Increased spending has also had a hand in fuelling labour market

shortages and steeply increased construction costs.[16]

Thus, in the case of roads, estimates suggest that construction costs per

completed road kilometre are up by as much as 30 per cent in an 18 month

period, meaning that the community is getting far less for the outlays than it

would have had the spending been better timed.[17]

On this point, Mr Ergas was unequivocal:

...[H]ave state governments, on balance, acted in a way which

increased or reduced those inflationary pressures? I would say they have acted

in a way which increased those inflationary pressures and have done so in a

manner that could have been avoided had they pursued a more stable approach to

the key spending decisions.[18]

6.18

Officials from the Treasury acknowledged the impact that the sudden

additional demand from states has on the economy:

If...the economy is in a position of full capacity, very simply

you are saying that the aggregate demand in the economy is more or less equal

to the supply potential of the economy. It is clear...that the investment by the

states in public infrastructure is adding to aggregate demand. [This investment

in infrastructure] will add to aggregate supply in time, but not immediately.

It adds to aggregate demand before it adds to aggregate supply.[19]

6.19

State government representatives in at least one jurisdiction rejected

the contention that infrastructure had not developed in a timely fashion. Western Australia's

Under‑Treasurer, Mr Tim Marney submitted that:

I think...our planning for infrastructure has been reasonably

robust and there have been some investments in capacity which have been long

term. If I went back to our advice at the time, probably it would have been,

'Yes, maybe that's a bit early' and it has proven to be timely, so I think that

it has been quite strategic of government to place greater emphasis on

expansion of the productive capacity of the economy as opposed to recurrent

spending on an ongoing basis.[20]

6.20

It would appear that the states were in a good position to increase

their investment earlier than they did. The committee heard that in 2005–06,

for example, the states and territories received $47.4 billion more revenue

than they had received in 1999–00 (or $22.1 billion more in real terms) and yet

only $2.1 billion of this was devoted to the net acquisition of non-financial

assets.[21]

This was despite the fact that during that time it was clear that significant

capacity shortages in state and territory infrastructure had developed.

Inconsistency leading to poorer service

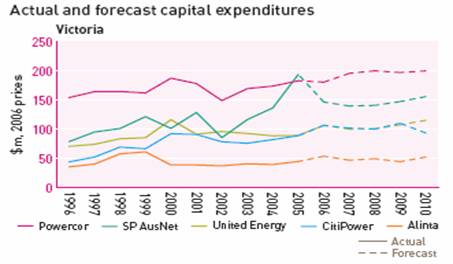

provision

6.21

The volatility of state government infrastructure investment is also

notable when contrasted with infrastructure investment by private sector

providers. An example provided to the committee concerned the levels of capital

expenditure undertaken by electricity distributors in Victoria, where

infrastructure is privately‑owned, and Queensland, where it remains

public, over the past decade. Whereas the privately-owned Victorian businesses

engaged in a relatively steady upward trend in investment, expenditure patterns

in the state-owned electricity distribution sector in Queensland have been much

more volatile, with relative stagnation in investment prior to 2003–04 followed

by high levels of 'catch up' investment from 2004.[22]

Figure 6.1—Capital Expenditure by Victorian Electricity

Distributors, 1996–2010

Source: Australian Energy

Regulator, State of the Energy Market Report 2007, p. 154.

Figure 6.2—Capital Expenditure by Queensland Electricity Distributors,

2001–02 to 2009–10

Source: Australian Energy

Regulator, State of the Energy Market Report 2007, p. 154.

6.22

Mr Ergas argued that the failure of the Queensland Government to invest

in a timely manner led to a serious reduction in the reliability of electricity

supply, and that outages in 2004 induced the Queensland Government to establish

an independent panel to review the service delivery of Queensland electricity

distributors. A key finding of the panel was that the distributors had focused

unduly on improving financial performance at the expense of undertaking capital

expenditure and maintaining service quality at acceptable levels.[23]

Quality of investment

6.23

Separate from the problem of timing and service provision is the issue

of selection of infrastructure projects to best serve the needs of taxpayers,

requiring careful and rigorous cost-benefit analysis.[24]

This was referred to by a number of witnesses as determining whether spending

constituted 'quality' investment.[25]

Mr Henry Ergas submitted that:

Unfortunately, the states and territories disclose virtually no

information about the evaluations undertaken of investment infrastructure

programs. Taxpayers cannot therefore have any real confidence that the debts

that are being incurred on major infrastructure projects will not simply

require substantially higher taxes in the years to come, taxes not offset by a

commensurate flow of benefits from the infrastructure projects undertaken.[26]

6.24

While inefficiencies in the allocation of infrastructure funds are

nothing new, the problems they create have been aggravated by the very

substantial investment by states in recent years. The committee heard that

public disclosure of cost-benefit analyses of all government-funded

infrastructure investment programs, regardless of jurisdiction, would increase

accountability for what are significant taxpayer-supported outlays.[27]

6.25

A case in point is the Victorian Government’s decision to spend over

$700 million upgrading regional passenger rail services, and to do so

without renewing the track with gauge-convertible sleepers. Mr Ergas considered

that, for a very modest expense, the government forewent what could have been a

significant feature of the project.[28]

6.26

Mr Kim Wells MP, Shadow Treasurer of Victoria, expressed his concern

over the projects being funded by the government in his state:

We would argue that if [debt] were being spent on issues of

productivity then you would understand that it is less inflationary. We have

asked the government for a full list of where they are applying this debt so we

can have a better understanding of what they are building to fix things,

because we do not see that at the moment.[29]

Management

6.27

As the scale of spending has increased, inefficiencies in the management

of that spending have become ever more obvious. New South Wales is a case in

point. The committee heard that in spite of a strategic plan for infrastructure

in New South Wales in 2002, by late 2004, an audit of 88 of the

key projects revealed $752 million in cost over-runs, one in four projects

delayed, and one in ten projects suspended or abandoned. By May 2006, the same

group of projects (with an estimated total project value of $11 billion), had

reached timetable blowouts of around 40 years, and cost blowouts of $1.7

billion. An assessment of the 2007–08 capital works budget papers shows 187

projects delayed, 219 years of total delays and an overall blow-out of

$2.6 billion.[30]

6.28

The situation appears similar in Victoria. Mr Kim Wells submitted that:

...The cost of the channel deepening started off at less than $100

million. It is closer to $1 billion. The fast train started off at $80 million

and they were going to get private involvement. That was just under a billion

dollars. We had the situation of the West Gate M1 contract which went from $1

billion to $1.363 billion. We have a list of almost $5 billion of those sorts

of cost overruns. It is of concern that poor financial management and poor

contract management are costing this state. We do understand that there are

cost increases over the life of a contract, but those cost blowouts are

significant.[31]

Public-Private Partnerships

6.29

One approach that aims to improve efficiency in infrastructure

investment involves greater reliance on Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs),

which are claimed to import to infrastructure investment the discipline of

private sector budget constraints. The assumption is that, since the providers

of finance secure no gains from politically popular but commercially unviable

projects, those projects that are not commercially viable will not be funded.

6.30

A number of witnesses pointed out that PPPs are not a suitable option

for every infrastructure project. The committee heard that, while PPPs deliver

on promises of efficiency in some cases, in others they fall short. Examples of

difficulties with PPPs include the Airport Rail link in Sydney and, to some

extent, the Sydney Cross-City Tunnel. The committee heard that both of these

projects involved substantial renegotiation, which materially altered the

effective risk allocation, highlighting the many difficulties involved in

designing effective PPPs. These difficulties are reflected in the high

transactions costs associated with establishing PPPs, with those costs usually

being in the order of between 3 and 10 per cent of construction costs.[32]

6.31

Mr Geoffrey Anderson, appearing in his private capacity, elaborated on

the rationale behind PPPs:

The first thing is that you do not do a PPP because you get

cheaper money. All treasury departments have quite specific guidelines for

PPPs—which are publicly available— and they set hurdles that they have to jump

over before they will agree to a PPP, which means the focus is then on taking

on risk. Of course it is very difficult at times to actually contract out all

risk. But I think governments are attracted to PPPs largely because they do

have the opportunity to transfer as much risk as possible, particularly

completion risk—and it is a big issue for governments to get buildings

completed on time—and to get other risks associated with the construction of

the project in somebody else’s hands. I think it is a more complicated issue [than]

purely financial. For a state like South Australia, I think it also brings

private investment, a commitment from people to bring business here. I think it

is a way in which governments can be involved with the private sector. I think

it is a way in which they can be assured they are going to get the right price

and the right management process all the way down the line. It has advantages.[33]

6.32

Mr Anderson went on to say that, in his opinion, the use of PPPs

differed depending on the political persuasion of the government. Mr Anderson

observed that:

What we are not seeing in PPPs in this state, because we have a

Labor government, is the traditional PPP. The traditional PPP was that the

company would build it and operate it and provide the service to the

government. We are not seeing that because that involves a degree of

privatisation which Labor governments are not prepared to accept—and maybe for

good reasons—but we are seeing them largely as financial and construction instruments.

A classic PPP was where the private sector would build the facility and staff

it and provide the service back to the government.[34]

6.33

On aspect of PPPs requiring significant improvement is the quality of

the contracts on which they are based, which according to the evidence do not

ensure optimal performance. Moreoever, particularly for projects that are 'too

big to fail', poorly designed PPPs may end up simply privatising profits while

socialising losses.[35]

6.34

Associate Professor Graeme Wines also observed that PPP agreements

typically operate over long periods of time, magnifying the need to assess risk

comprehensively.[36]

Associate Professor Wines also used the agreements entered into for the

Cross-City Tunnel in Sydney, as well as the CityLink in Melbourne, as examples

of contract terms that severely limited the scope for development of adjacent

public roads. Indeed, these contracts actually resulted in restrictions for

some adjacent roads, and these restrictions will continue for the period of the

respective agreements. These restrictions have accordingly limited the policy

options, with respect to road infrastructure in these examples, for the

respective governments.[37]

6.35

The implications of the need for private sector entities to produce a

positive return for shareholders over and above their higher interest costs

must also be considered for any potential PPP projects, along with the higher

interest rates usually offered to private sector borrowers.

6.36

The committee heard various reports of PPPs being misused by state

governments. Queensland Shadow Treasurer, Dr Bruce Flegg MP submitted that the

Queensland Government had mismanaged the use of PPPs to generate 'fast cash'

rather than to generate economic efficiency and savings.[38]

6.37

A possible example of this kind of misuses was given by Ms Vicky Chapman

MP, Deputy Leader of the Opposition in South Australia:

The big picture items here in South Australia are prisons,

schools and the $1.7 billion Marjorie Jackson-Nelson Hospital, which is really $1.9

billion because there is $200 million over in the transport budget to clean up

the rail yards it is going to go on—so it is nearly a $2 billion project. These

are big projects and, quite reasonably, the government looks at whether they PPP

them, but we have done the exercise and the cost under their PPP model is going

to bankrupt our grandchildren. That is the way we see it, and we are very

concerned about that...[W]e say that on the government’s own financing for $1.4

billion it could completely rebuild the hospital on the current...site. That is

our proposal; that is our clear position.[39]

The proper role of the Commonwealth

6.38

A small number of witnesses commented on what they saw as the proper

role of the Commonwealth Government in relation to the provision of

infrastructure into the future. The prevailing view was that the Commonwealth

had a role to play.[40]

The effect of vertical fiscal imbalance puts the Commonwealth Government in a

stronger position to fund large projects, and possibly to realise economies of

scale. However, Mr John Nicolaou, from the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Western

Australia, put forward another reason for Commonwealth involvement:

I think that both the Commonwealth and states have a

responsibility. The states really are responsible for the basic delivery of key

infrastructure because many of the deliverers of infrastructure are government

owned entities, and certainly I agree with that. But in relation to

infrastructure that is not owned by the state per se, I think that the

Commonwealth can take a bigger role. We only have to highlight some of the

perverse incentives that are created if the Commonwealth gets significant

amounts of revenue and benefits from infrastructure provision while the states

at the same time have to fund that infrastructure and get far less in terms of

revenue. Clear examples of that are the infrastructure on the Burrup, and the

Gorgon project when that comes on stream, and even the Ravensthorpe nickel

project. Those are areas where the state has a responsibility to provide common

user infrastructure, but the majority of the revenue benefits go to the

Commonwealth in terms of royalties, income tax and so forth.[41]

6.39

The committee finds some merit in this argument. It sees a legitimate

role in some circumstances for the Commonwealth to accept a greater share of

responsibility for infrastructure than it might have in the past. Whether the

recently established Infrastructure Australia is a step in this direction will

depend on how that body operates and on what principles.

6.40

However, some evidence was received pointing to the need for caution in

defining the role of the new body. For example Dr Steve Thomas MLA, Shadow

Treasurer for Western Australia, said that he was:

...hoping at some point that there will be an additional mechanism

for the Commonwealth to engage in the construction of that infrastructure. We

will look very carefully at Infrastructure Australia, the new group which is

providing infrastructure. We will be watching that very carefully. If its

agenda is to provide resources and infrastructure for high population density areas

and if it ends up building roads between Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne and

Canberra and does not look at future proofing the country and investing in infrastructure

which builds the country, in the north-west of Western Australia in particular,

and also to some degree, I suspect, in Queensland and the Northern Territory,

then Infrastructure Australia will be one of the great failures of Australian

history. If it does the job that we think it should do, it may be one of the greatest

success stories we have ever seen.[42]

6.41

The need to reform state government infrastructure decision-making was

also addressed by Concept Economics:

If Infrastructure Australia proves little more than a vehicle

for transferring Commonwealth funds to state governments without reform of

infrastructure decision-making and governance arrangements, it has the

potential to merely waste taxpayers’ money. Large-scale investment from a

Building Australia Fund, or indeed from any other public sector source, does

not absolve the Commonwealth Government of its responsibility for ensuring that

state and Territory governments improve their decision-making processes and

tackle pressing regulatory problems that, in some cases, are holding back

commercial investment in much-needed infrastructure.[43]

Conclusion

6.42

The committee notes the sub-optimal state of the infrastructure pool

across Australia, and makes the obvious point that it is crucial to get infrastructure

investment right. Infrastructure assets are, by their nature, difficult to

replicate, and some are natural monopolies. If development and renewal of

infrastructure is mismanaged at government level, the resulting bottlenecks are

likely to impose severe constraints on economic growth.

6.43

While the committee was pleased to hear that investment by states and

territories has picked up over past two years, and that infrastructure renewal

is taking place, it is concerned at some aspects of the investment. These concerns

were captured by Mr Henry Ergas when he made the following remarks, citing

two primary concerns with the way states had managed infrastructure spending in

recent years:

The first is with the timing of the expenditures and the

management of the timing of the expenditures, and the second is with the

quality of the expenditures. The issue with respect to the timing is

particularly acute with respect to infrastructure in that we had a relatively

prolonged period where, albeit with some variations between jurisdictions, the

states and territories tended to reduce or severely constrain their

infrastructure spending, and then following that period we had a period where

there was almost a spending spree associated with catching up on the shortfalls

that had accumulated initially. It is bad enough to have that kind of stop-go

cycle, which under any circumstances increases costs unnecessarily, but even

worse to have that stop-go cycle coincide with overall cyclical movements in

the economy, which means that you, as it were, open the tap to the full just as

the economy is going into what looks like a period of overheating or at least

where labour markets and product markets are very tight. Hence, you accentuate

all of the inflationary pressures underway in the economy. That in my view

highlights a serious failure of policy.

On top of that you then have my second concern, which is about

the quality of outlays. It is the responsibility of state governments to

undertake significant long-term investments, and it is sensible for state

governments to finance those long-term investments, including through

borrowings. There is nothing inherently sinful or undesirable in that. But

those borrowings essentially represent a tax liability for future generations

or future periods, and hence the quality of the outlays is essential. If those

are good quality outlays that will yield long-term benefits and enhance the

productive capacity of the economy then future generations will find it easy to

bear the associated tax burdens because productive potential will have

increased at the same time as some costs have been deferred to the future. On

the other hand, if those outlays do not expand productive capacity in the long

term, if they are not worth while, then all that is really being done is to

make future generations poorer than they would otherwise be.[44]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page