Chapter 3

The carbon tax the Prime Minister promised

we wouldn’t have

Introduction

3.1

This chapter outlines the key features of the carbon tax which were

released on 10 July 2011 and subsequently updated with the introduction of the

Clean Energy Legislative Package into the Parliament on 13 September 2011.

The carbon tax is announced

3.2

On 10 July 2011, the Prime Minister, the Hon. Julia Gillard MP,

announced her plan to introduce a carbon tax. The Prime Minister stated:

... we have now had the debate, 2011 is the year we decide

that as a nation we want a clean energy future.

Now is the time to move from words to deeds.

That’s why I announced today how Australia’s carbon price

will work.

From 1 July next year, big polluters will pay $23 for every

tonne of carbon they put into our atmosphere.[1]

Features of the carbon tax

3.3

This part of this chapter outlines the key features of the carbon tax.

Start date and transitional period

3.4

Starting from 1 July 2012, the price of each tonne of carbon dioxide

emissions will be fixed, operating as a carbon tax (the fixed-price period). The

initial starting price '... will be $23 for each tonne of pollution beginning

on 1 July 2012'.[2]

The carbon tax will be in operation for three years. Under the government's

carbon tax, 'the price will rise by 2.5 per cent a year in real terms during a

three-year fixed price period until 1 July 2015'.[3]

3.5

Then, from 1 July 2015, the carbon tax will move to an emissions trading

scheme where the price will be set by government imposed limits on the

permissible amount of carbon dioxide emissions in any one year (the

flexible-price period).[4]

3.6

The table below provides an overview of the revenue that will be collected

from the carbon tax, and associated changes that form part of the government's

carbon tax, according to Treasury modelling.

Table 3.1: Revenue from the carbon tax and associated

measures[5]

|

Year

|

Revenue from carbon tax ($m)

|

Revenue from carbon tax applied via other measures ($m)

|

Fuel tax credit reductions ($m)

|

Total per year ($m)

|

|

2011-12

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

2012-13

|

7,740

|

290

|

570

|

8,600

|

|

2013-14

|

8,690

|

320

|

70

|

9,080

|

|

2014-15

|

9,190

|

320

|

70

|

9,580

|

|

Total

|

25,620

|

930

|

710

|

27,260

|

3.7

An equivalent carbon tax will also apply to synthetic greenhouse gasses

and aviation fuels.[6]

The carbon permit a property right?

3.8

Under the Clean Energy Bill 2011:

Section 103: A carbon unit is personal property and, subject

to sections 105 and 106, is transmissible by assignment, by will and by

devolution by operation of law.[7]

3.9

The Explanatory Memorandum for the Clean Energy Bill does not explain

why a carbon unit is clearly defined as personal property.

3.10

The direct consequence of defining a carbon unit as personal property is

to make it more likely that:

Repeal would amount to an acquisition of property by the

commonwealth, as holders of emissions permits would be deprived of valuable

asset[s].[8]

3.11

In these circumstances, under section 51(xxxi) of the Australian

Constitution, a government acquiring these assets would be required to 'pay

compensation, potentially in the billions of dollars. A future government

would therefore find repeal prohibitively costly'.[9]

3.12

The definition of a carbon unit as a personal property right limits the

scope of action of future governments and parliaments. As economist Professor

Henry Ergas has noted:

...internationally, governments have generally ensured that

pollution permits are not treated as conventional property rights, precisely as

to be able to revise environmental controls as circumstances change. Rather,

this provision serves one purpose only: to guarantee any attempt at repeal

triggers constitutional requirements to pay compensation, shackling future

governments.[10]

3.13

The committee explored the issue further and sought advice from the

Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency on permits and their

standing as personal property rights:

Senator BOSWELL: In particular, have you received any

advice about the liability of a government which removed the carbon

legislations thus removing any value of it in a carbon unit? So, we come into

power and we say: 'No, we are not having this.' What happens to that carbon

unit?

Mr Sakellaris: I do not recall the details, we would

have to take that on notice.

Senator BOSWELL: When did you ask for advice, when did

you receive the advice on this particular issue? What did that advice say? Has

the department evaluated what the size of any potential future liability will

be?

Dr Kennedy: For the last part of the question I can

say that the department has not done any analysis around the possible repeal of

the system and what the cost would be. As to all the previous questions about

when advice was taken, we have not brought our legal advisors with us but we

are very happy to take all those questions on notice and provide you with an

answer.

Senator BOSWELL: I will read them out again. When did

you ask for that advice and when did you receive it? What did the advice say?

Has the department evaluated what the size of any potential future liability

will be?

Dr Kennedy: We had a person from the Australian

Government Solicitor working throughout the pulling together of the

legislation. So, if you like, we were receiving advice on an ongoing basis, but

we also sought additional—

Senator BOSWELL: You cannot give me what I am asking

now, you are prepared to take that on notice.

Dr Kennedy: I can, but I wanted to let you know that a

lawyer from the Australian Government Solicitor worked with us all the way

through, so in a sense advice was provided as it was done. But we can answer

your questions about whether particular pieces of advice were sought external

to the department. We are happy to do that.

Senator BOSWELL: And when you received it and what it

said, and its potential size of future liabilities.

Dr Kennedy: As I said I do not think we have done any

analysis at all on potential liability because we have not evaluated the

scenario of repealing the scheme.[11]

3.14

In its response to the questions taken on notice, the Department of Climate

Change and Energy Efficiency noted that they:

... received legal advice on the effect of section 51(xxxi)

of the Constitution, relating to the acquisition of property on just terms,

on repeal of the legislation. The advice was requested on 16 September 2011 in

view of the interest in this issue in the Parliament and in the media, and

draft advice was received on 21 September 2011.

Legal advice is subject to legal professional privilege.

The Department has not evaluated the size of any potential

future liability of a government that removed the clean energy package of

legislation.[12]

Committee Comment

3.15

The committee considers that it is highly irresponsible and

inappropriate for a government seeking to implement a carbon tax in clear

defiance of an explicit pre-election commitment and to deliberately expose

Australian taxpayers and the economy to these significant costs in its efforts

to prevent future governments from implementing a mandate to rescind such a tax

based on its assessment of the national interest.

3.16

This is all the more the case given the uncertainty that currently

surrounds the future international environment for climate change policy. Given

that uncertainty, the proper course is to seek and retain flexibility, rather

than lock-in a path that may prove both futile and costly.

How will the carbon tax work?

3.17

The carbon tax will work in the following way:

Large polluters will report on their emissions and buy and

surrender to the Government a carbon permit for every tonne of carbon pollution

they produce.

In the fixed price period, as many carbon permits as

businesses require to meet their obligations will be available at the set

price. This will operate like a carbon tax on around 500 polluters.[13]

Liable businesses will need to buy and surrender to

the Government a permit for every tonne of pollution they produce.

-

In the fixed price stage, that runs from 1 July 2012 to 30 June

2015, the carbon price will start at $23 per tonne and rise by 2.5 per cent a

year in real terms.

-

From 1 July 2015 onwards, the price will be set by the market

and the number of permits issued by the Government each year will be capped.

If businesses can lower their pollution, the price they pay will

be less. This is how the carbon price drives innovation and energy efficiency.

All revenue from the carbon price will be used by the Government

to:

-

assist households with price impacts they face by cutting taxes

and increasing payments

-

support jobs and competitiveness

-

build our new clean energy future.[14]

Coverage

3.18

The carbon tax will apply to facilities that have direct emissions of 25

000 tonnes or more a year of carbon dioxide equivalent, with some exclusions.[15]

This is expected to be around 500 carbon emitters.[16]

3.19

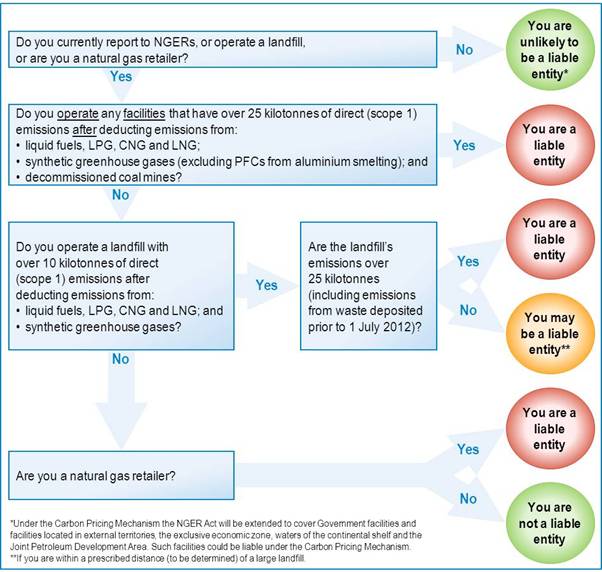

The graphical representation below provides an overview of how the scheme

will rule in and rule out what businesses are covered by the carbon tax.

Graphic 3.1: Coverage of the carbon tax[17]

|

NGERs – National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting

Scheme

|

|

3.20

The government has not released the names of the emitters that it

believes will be covered by the carbon tax. However, on 18 July 2011 the Parliamentary

Library released a paper listing the top 299 emitting companies (remembering

that the tax is based on individual facilities rather than corporations), using

information provided under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme.

3.21

The Parliamentary Library notes that:

... although imperfect, the NGER data is the only public

information that provides any indication as to which companies may be liable

under the proposed Carbon Pricing Mechanism.[18]

3.22

The carbon tax does not apply to certain industry sectors and energy

forms. The agriculture sector is excluded from the carbon tax[19]

and closed landfills are exempt from the carbon tax as well.[20]

In addition, parts of the transport sector, for example, fuels used by

passenger cars and light commercial vehicles, are also exempt.[21]

3.23

Of the liable businesses, it is estimated that around:

-

135 operate solely in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory;

-

110 solely in Queensland;

-

85 solely in Victoria;

-

75 solely in Western Australia;

-

25 solely in South Australia;

-

20 solely in Tasmania; and

-

fewer than 10 solely in the Northern Territory.[22]

3.24

A further 45 liable entities operate across multiple states.

3.25

Of the estimated 500 businesses:

-

around 60 are primarily involved in electricity generation;

-

around 100 are primarily involved in coal or other mining;

-

around 40 are natural gas retailers;

-

around 60 are primarily involved in industrial processes (cement,

chemicals and metal processing);

-

around 50 operate in a range of other fossil fuel intensive

sectors; and

-

the remaining 190 operate in the waste disposal sector.[23]

3.26

The issue of the number of businesses covered by the carbon tax was

raised by the committee during the course of its inquiry. The government has

indicated that around 500 emitters would be covered by the carbon tax but this

number was questioned. The challenge is about the number of small businesses

that will be caught under the government's changes to fuel tax:

CHAIR: I am looking at the exposure draft, page 5,

43(8), 'Working out the amount of carbon reduction'. This clause effectively

imposes a carbon price on fuel through a reduction in the fuel tax credit, does

it not?

Mr Comley: That is correct.

CHAIR: Essentially, it contains a formula. The credit

for taxable fuel or the fuel tax rebate is reduced by a formula that is the

quantity of fuel times the carbon price times the carbon emissions rate.

Doesn't this mean that recipients of the fuel tax rebate are paying a carbon

price from the word go by the wording of your own legislation?

Mr Comley: It certainly means that they are having a

reduction in their credit linked to the carbon price, yes.

CHAIR: From day 1, as of 1 July 2012 under your

exposure draft?

Mr Comley: Yes, that is correct.

CHAIR: I thought that that was correct, which is not

entirely consistent with the proposition that fuel has been excluded from the

carbon pricing package that has been released by the government.

Mr Comley: The documents make it clear that there is

coverage of the transport sector. In fact, if I were to turn to both the policy

tables and the full clean energy document, it is clear that transport is

covered in some part. There are exclusions for small on-road vehicles under 4.5

tonnes. But it is entirely consistent with the documentation that has been

provided.

Senator WILLIAMS: So are you telling us that the 6.21c

a litre on the rebate for transport of more than 4.5 tonnes tare weight will

start on 1 July 2012?

Mr Comley: No—sorry Senator. For the large vehicle

issue, there is a government commitment to start on 1 July 2014. The fuels

being referred to here are a fuels related effectively to off-road use.

CHAIR: And of course the expected revenue which the

government intends to include, in terms of transport fuels, into the carbon

pricing regime from 2014-15 has been included in the costings of the package,

too, has it not?

Mr Comley: It is part of the forward estimates, yes.[24]

3.27

Seeking further information about the impact of the change to the fuel

tax, the committee challenged the notion that only 500 companies would be

caught by the tax with the Department of the Treasury:

Senator BOSWELL: Yes, how many will be subject to

carbon price on fuel from July 2011?

CHAIR: 2012, I think.

Senator BOSWELL: Okay, we will make it 2012.

Mr Heferen: We would have to take that one on notice.

Senator BOSWELL: Based on Taxation Office data, 60,000

businesses including small business will pay a carbon price. Not just the 500

big polluters. Will those 60,000 businesses start paying a carbon price by

2012?

Mr Heferen: Is the reference to the 60,000 businesses

those which would have had their fuel tax credit adjusted?

Senator BOSWELL: Yes.

Mr Heferen: I think that relates to the question

before, which would be the question of how many businesses will be affected. We

have to take that on notice.[25]

3.28

At the time of finalising the report, no reply to the Question taken on Notice

had been received by the committee.

Australia's carbon emissions

reduction targets - binding future governments

3.29

The government has committed to reducing carbon emissions by 5 per cent

from 2000 levels by 2020 and by up to 15 or 25 per cent depending on the scale

of global action.

3.30

Under the Clean Energy Bills, a 'carbon pollution cap' will be put in

place through regulations, allowing the government to review the target as

circumstances change in accordance with defined principles.[26]

3.31

The exposure draft includes a mechanism for setting a default carbon emission

cap should there not be any regulations in effect. While the regulation

containing proposed 'carbon pollution caps' may be disallowed by either House

of Parliament, this will not stop the scheme from continuing its operation, as

explained by the Explanatory Memorandum to the Clean Energy Bill 2011:

2.8 Having a default in the legislation ensures that the

mechanism continues to operate in the event that regulations setting pollution

caps do not come into effect. The default cap follows a trajectory consistent

with Australia's unconditional target of reducing national emissions to five

percent below 200 levels by 2020, taking into account projections for emissions

from uncovered sectors (including the impact of emissions reduction measures on

those sectors).[27]

3.32

The consequences of this legislative design were clearly identified by

economist, Professor Henry Ergas, who noted that:

... unless the government can secure a majority for an alternative

target, permitted emissions are automatically cut by up to 10 per cent in a

single year crippling economic activity.

A Coalition government, or even a Labor government less

wedded to the Greens, would therefore find itself trapped.[28]

3.33

Under the legislation, these automatic reductions in carbon emissions

are not a disallowable instrument. That is, to prevent automatic increases in

the carbon tax, or the trading price of emission permits, both Houses of Parliament

would need to pass legislation to that effect. As the Explanatory Memorandum to

the Clean Energy Bill 2011 states:

Default pollution caps exist in the event the regulations

setting pollution caps do not take effect. This is only a concern when

regulations setting pollution caps are either not tabled in the Parliament by

the deadline or are tabled and then disallowed.[29]

3.34

In contrast, any Ministerial decision to reduce carbon emissions by more

than the default amount is a disallowable instrument, meaning that only one

house of parliament need vote against this decision to have it disallowed.[30]

In effect, under the government’s clean energy legislation, in the future taxes

can increase even without the approval of the House of Representatives, even

though the House is given the exclusive constitutional power to raise taxes.[31]

Australia's carbon emissions

reduction targets

3.35

The government has committed to reduce carbon emissions by 5 per cent

from 2000 levels by 2020 and by up to 15 or 25 per cent depending on the scale

of global action. Though the target is one that has bipartisan support, the

opposition disagrees about the mechanism by which the target might be reached. It

should be noted that this target is not included in the Clean Energy Bill introduced

into Parliament on

13 September 2011. Rather a 'carbon pollution cap' will be put in place through

regulations, allowing the government to review the target as circumstances

change, in accordance with principles set out in the Bill. The Bill does

include a mechanism for setting a default carbon pollution cap should there not

be any regulations in effect.

3.36

Under the Government’s carbon tax scheme, Australia’s emissions to 2020

will actually rise by around 90 million tonnes. The only way Australia will

meet its 5% target will be as a result of the purchase of international

permits. Therefore, the Government will be implementing a new tax that, from

the outset, will not actually achieve its desired aim.

3.37

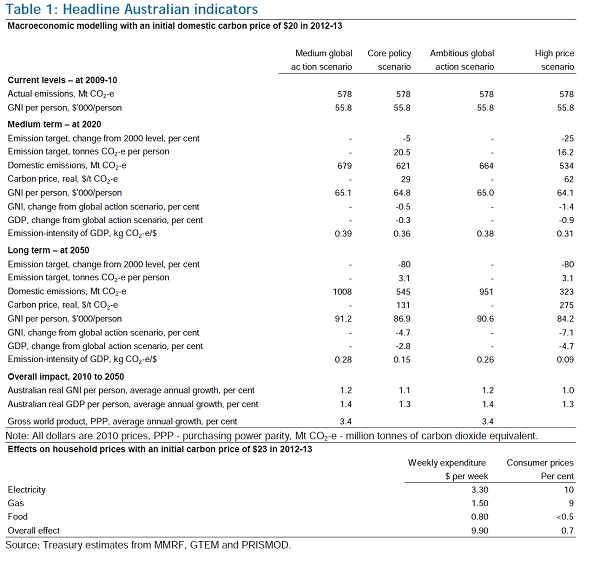

The table below highlights the policy dimension of this. In 2009-10

Australia emitted 578 million tonnes, but by 2020 it will be 679 million

tonnes. So despite slower GDP growth and slower growth in real wages,

emissions will be 90 million tonnes higher. These are the government's own

figures.

Table 3.2 Headline Indicators[32]

3.38

These targets will require cutting forecast emissions by at least 23 per

cent in 2020.[33]

Importantly:

The Government also commits to a new 2050 target to reduce

emissions by 80 per cent compared to 2000 levels, in line with targets

announced by the United Kingdom and Germany.[34]

Regulatory and governance structure

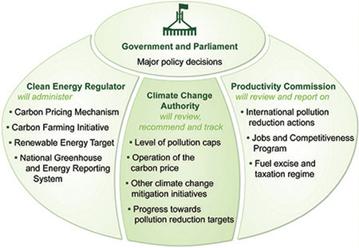

3.39

The governance structure for the scheme is set out in the graphic below.

The Australian government and the Minister for Climate Change and Energy

Efficiency are responsible for setting the overall policy direction for climate

change.

3.40

The Climate Change Authority will recommend pollution caps and oversee

the operation of the flexible carbon permit trading market. The Clean Energy

Regulator will administer the scheme that enables the trading of permits. The

Productivity Commission will conduct ad hoc reviews into climate change matters

at the direction of the government and will review the compensation provided

under the scheme but not the direct spending on, for example, the Clean Energy

Finance Corporation. As a result, significant Commonwealth expenditure will not

be subject to regular, independent scrutiny.

Graphic 3.2: Governance arrangements for the carbon tax[35]

Good money after bad

3.41

Prior to the announcement of the framework for the Clean Energy Plan and

the institutions outlined above to administer the carbon tax, the government

had already started allocating resources to the climate change cause.

Australian

Competition and Consumer Commission

3.42

The government announced on 13 July 2011 that the Australian Competition

and Consumer Commission (ACCC) would be policing claims by businesses that

could mislead consumers into believing that price rises had occurred due to the

carbon tax when this was not the case.

3.43

The funding for the ACCC to undertake this activity is:

... $12.8 million over four years to the ACCC and those funds

will go towards the establishment of a dedicated team which will involve more

than 20 staff and their activities will be directed towards enforcement and

towards education of businesses and consumers.[36]

3.44

This measure was not included as a cost in the government's Clean Energy

Plan announced on 10 July 2011.

Other regulatory agencies

3.45

In addition to the establishment of the regulators referred to above, other

agencies who will be involved in the implementation of the government's Clean

Energy Plan are:

-

the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA); and

-

the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC).

3.46

ARENA will be a statutory authority, set up to provide funds for

research, development and commercialisation of renewable energy technologies.

It will incorporate a number of existing programs, such as the Australian

Centre for Renewable Energy, the Australian Solar Institute and the Australian

Biofuels Research Institute. It is projected to be revenue neutral, as it will

utilise $3.2 billion of funding already allocated to those programs over nine

years. The government's plan is that future funding for ARENA will come from

dividends paid by the Clean Energy Finance Corporation.[37]

3.47

The role of the CEFC will be to invest in the commercialisation and

deployment of renewable energy, energy efficiency and

low-emissions technology. It has allocated funding under the Clean Energy Plan

of $10 billion over five years from 2013-14.[38]

3.48

The CEF was subject to inquiry during the course of the committee

undertakings its public hearings. The corporation is a part of the regulatory

architecture for the overall carbon tax scheme but despite this its exact

status remains unclear:

CHAIR: The carbon tax package said that no decision

had yet been made whether the Clean Energy Finance Corporation would sit in

Treasury or in the Finance portfolio. Has this been resolved?

Mrs McCulloch: It has not yet been finalised.

CHAIR: When is that expected to be finalised?

Mrs McCulloch: Discussions are ongoing with the

government, including in relation to appointments to the CEFC.[39]

3.49

The reason for the inability of the government to determine which

Minister will have responsibility for the CEFC opens the way for speculation

about whether disagreements between Ministers or departmental secretaries is

driving the delay.

3.50

The CEFC will be responsible for a substantial amount of public funds,

some $10 billion dollars in total. The committee was very much interested in

the corporations and the decisions surrounding its creation:

CHAIR: Did the government or the Multi-Party Climate

Change Committee seek advice from Treasury on the Clean Energy Finance

Corporation before a decision was made to establish it?

Mrs McCulloch: Treasury provided advice on the package

in its entirety, including the Clean Energy Finance Corporation.[40]

3.51

The committee pursued the matter further and sought information about

the rationale for a public sector organisation competing with private

businesses in the provisions of loans:

CHAIR: I am seeking an explanation as to what the

policy basis is for a government-financing entity providing commercial loans to

private sector energy companies? By definition, if they are commercial loans

why can companies not source their loans from the private sector?

Mrs McCulloch: Commercial in that sense does not

necessarily mean the market rate or the hurdle rates that that these businesses

would need to go through. There are a large number of potential clean energy

and renewable projects out there that cannot get finance for a range of reasons

and the purpose of the entity, the CEFC, is to leverage private sector

investment in this area.

CHAIR: So the Clean Energy Finance Corporation will

provide loans and equity and they are not quite commercial because you are

saying that they are pitched at a level that would not necessarily be market

level?

Mrs McCulloch: Commercial is, in that sense, intending

that they will earn a positive return.

CHAIR: What sort of positive return?

Mrs McCulloch: I will have to take that on notice. I

do not know that detail.[41]

3.52

The response from Treasury to the question taken on notice, in its

entirety is:

Recipients

of commercial loans provided by the CEFC are expected to be charged an interest

rate comparable to that offered by lenders in the private sector.

The

objective of the CEFC is to remove market barriers that would otherwise hinder

the financing of large-scale clean energy and renewable projects. That is, the

CEFC will operate in the ‘market gap’, encouraging projects that wouldn’t

otherwise proceed by providing an alternative source of debt or equity to

underpin a project’s financial viability.[42]

3.53

While the Clean Energy Finance Corporation will be providing a variety

of loans, some of which are to be non-commercial, this invariably gives rise to

concerns about the fiscal impact of such organisations on the Commonwealth

Budget:

CHAIR: I refer to the costings that you referred me to

before, on page 131, of the plan document. How come the Clean Energy Finance

Corporation has a fiscal impact of $944 million over the forward estimates?

Mrs McCulloch: That costing includes things like the

administration—the actual running costs of the CEFC. It also includes an

allowance for some concessional loans—some loans that are below the government's

bond rate—and it also allows for some prudent estimation of defaults. It is

standard.

CHAIR: Out of $10 billion, you are expecting nearly $1

billion will go to administration, defaults and non-commercial loans or equity?

Mrs McCulloch: They are a portion of the costings,

yes.

CHAIR: Are you able to provide us the detail of what

makes up that $944 million? How much of it is administration? How much of it is

an estimate of defaults? How much of it is an estimate of what you call

concessional loans?[43]

3.54

Treasury also took these questions on notice and replied:

The fiscal

impact of $944 million across the forward estimates reflects the net impact of

revenue and expenses excluding public debt interest costs. Departmental expense

is equal to $60 million over the forward estimates.

Over half

is explained by the expense associated with concessional loans and the

remainder is largely explained by the allowance that is made for defaults.

The funding

provided to the CEFC will impact on gross debt. To the extent that the CEFC

acquires offsetting debt-like assets, such as loans, there will be a lesser

impact on net debt.

Treasury

expects that taxpayers will, over time, receive interest and dividends. That

is, taxpayers will get a positive return on the investment.[44]

3.55

The inevitable outcome of a government-owned financing corporation

providing funds to industry is the age-old issue of picking winners. During the

1980s various state governments were engaged in this practice with the

electorates across Western Australia, South Australia and Victoria left to pick

up the pieces:

CHAIR: Essentially this is back to governments picking

winners in supposedly commercial transactions, though, isn't it? Have you

looked at the history of Tricontinental, the State Bank of South Australia and

WA Inc. to better manage the risk that eventuated in those circumstances, where

governments lost billions picking winners in what were supposedly commercial

transactions? Is the risk management framework more robust than what it was at the

time?

Mrs McCulloch: The government has announced that it

will appoint a chair to conduct a review over a period of about six months,

reporting early next year, to assess a risk management framework, provide

advice to government on an appropriate investment mandate and look at issues

around the establishment of the CEFC—what function and form it takes. The risk

management frameworks have not been established yet. The government is seeking

advice, including from experts in the financial sector.

CHAIR: I am sure that with the Tricontinental, State

Bank of South Australia and WA Inc. examples there were chairs of boards. I am

sure that they had corporate governance frameworks and reviews of risk

management and so on. Governments getting involved in this sort of business and

trying to pick winners is not really a very good way of dealing with taxpayers'

money. But that is just my view.[45]

3.56

To the extent that picking winners is successful or unsuccessful, there

will be an impact on the Commonwealth Budget:

CHAIR: I am giving that as an example to make a point.

The point is this: if the government is taking equity through the Clean Energy

Finance Corporation, what is the accounting treatment when the value of shares

drops, for example, from $1.50 to 25c?

Mrs McCulloch: That would affect the government's

balance sheet, just like it does with any other equities that it enters into.

CHAIR: So it would affect the government's balance

sheet?

Mrs McCulloch: Yes.

CHAIR: Are you quite sure of that?

Mrs McCulloch: Yes. The government's balance sheets

takes into account all of its assets and liabilities.

CHAIR: Except that the Clean Energy Finance

Corporation of course as a whole is off budget.

Mrs McCulloch: No, it is within the general government

sector and therefore on the government's balance sheet.

CHAIR: Except that you are assuming that you are going

to make a return. You are saying that, to the extent that that does not happen,

that will be obvious; that will be transparent.

Mrs McCulloch: There are two distinctions here. The

figures that you are looking at in the document are the cash and fiscal flows

on an annual basis. Then there is also the balance sheet—what does it do for

gross debt, for the government's asset position and for net debt? The CEFC is

incorporated in the government's balance sheet.[46]

3.57

The committee pursued the matter:

CHAIR: How is the accounting treatment of the Clean

Energy Finance Corporation determined? How subcommercial would a Clean Energy

Finance Corporation transaction have to be before it was treated as a subsidy

that had a fiscal impact? Is it, as you have just mentioned, as soon as it is

below the bond rate that it hits the budget bottom line?

Mrs McCulloch: I would have to double-check the exact

definition. The accounting standards here are consistent with the ABS GFS

guidelines and consistent with the way Finance do the costings for these types

of entities. Exactly the definition used for what is concessional, I will take

on notice.[47]

3.58

The reply from Treasury to the question taken on notice, in its

entirety, stated:

The Charter

of Budget Honesty Act 1998 requires that the budget be based on external

reporting standards. The budget treatment of CEFC is consistent with accounting

and budget rules.

Concessional

loans are loans that charge an interest rate below the market interest rate.

The

accounting treatment of concessional loans involves an upfront impact to the

fiscal balance and net debt (to the extent of the concession). As repayments

are made, this impact is unwound over the life of the loan.

The impact

to the underlying cash balance is limited to the net of interest receipts and

interest payments.

Treasury

expects that taxpayers will, over time, receive interest and dividends. That

is, taxpayers will get a positive return on the investment.[48]

Advertising and community awareness

3.59

On 16 June 2011, almost a month before it unveiled its plan, the

government announced a national advertising campaign to sell the carbon tax.

The Minister for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, the Hon. Greg Combet AM

MP, has stated that the campaign will cost $12 million. This is in addition to

an allocation of $8.2 million in the 2011-12 Budget for the Climate Change

Foundation Campaign, which will fund a $3 million grants program, as well as

'partnerships and other community engagement activities'.[49]

3.60

It has been suggested that the total cost of all government advertising

to support its carbon tax is closer to $25 million, when the cost of leaflets

and websites is added in.[50]

Compensation for households

3.61

The government has indicated that the price impact of its carbon tax

will mean that '[o]n average, households will see cost increases of $9.90 a

week, while the average assistance will be $10.10 a week'.[51]

3.62

As a tax, the carbon tax and related measures will raise around $27.2

billion between 2012-13 and 2014-15. The government has announced that '[m]ore

than half of the revenue raised by putting a price on carbon pollution will go

to households to help meet price impacts'.[52]

3.63

Chapter 7 explores the impact of the carbon tax on households in more

detail.

For households under the carbon tax

3.64

Under the government’s carbon tax, a new Clean Energy Supplement will be

paid. The assistance will mean up to:

-

$110 per child for a family that receives Family Tax Benefit Part

A;

-

$69 extra for families that receive Family Tax Benefit Part B;

-

$218 extra per year for single income support recipients and $390

per year for couples combined for people on allowances; and

-

$234 per year for single parents, in addition to the increased

family payments they receive.[53]

3.65

The '[p]ayments of the Clean Energy Supplement will be paid on a

fortnightly basis from March 2013 for most allowances, July 2013 for family

payments and January 2014 for students on Youth Allowance'.[54]

For pensioners under the carbon tax

3.66

Under the government’s carbon tax:

A new Clean Energy

Supplement will be paid, equal to a 1.7 per cent increase in pensions, allowances

and family payments. The assistance will mean:

-

Up to $338 extra per year for

single pensioners and self-funded retirees, and up to $510 per year for

pensioner couples combined.[55]

3.67

The '[p]ayments of the Clean Energy Supplement will be paid on a

fortnightly basis from March 2013 for pensions and most allowances'.[56]

Reform of income taxation

arrangements

3.68

Under the carbon tax, a range of income taxation reform measures will

also be introduced. These include:

From day one of the carbon

price on 1 July 2012, every taxpayer with income below $80,000 will receive a

tax cut, with most getting at least $300 a year.

These tax cuts will be

permanent, and they will increase. On 1 July 2015, a second round of tax cuts

will apply, increasing the saving to at least $380 a year for most taxpayers

earning under $80,000 compared to now.[57]

3.69

Taken together:

The combined changes mean

headline tax rates will better match the effective rate that a lot of taxpayers

are actually paying at the moment. All taxpayers under $80,000 will pay less

tax.[58]

Cost of household assistance measures

3.70

The cost of all household assistance measures are set out in the table

below.

Table 3.3: Cost of household assistance under the carbon tax[59]

|

Year

|

Increases in transfer payments ($m)

|

Tax Reform ($m)

|

Low Carbon Communities ($m)

|

Other energy efficiency measures ($m)

|

Implementation of assistance ($m)

|

Totals

($m)

|

|

2011-12

|

1,470

|

0

|

5

|

7

|

51

|

1,543

|

|

2012-13

|

775

|

3,350

|

39

|

13

|

54

|

4,230

|

|

2013-14

|

2,302

|

2,370

|

83

|

15

|

39

|

4,890

|

|

2014-15

|

2,380

|

2,320

|

90

|

13

|

28

|

4,830

|

|

Total

|

6,927

|

8,040

|

217

|

48

|

172

|

15,403

|

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding. Numbers in the above

table are those contained

in the source document.

3.71

Chapter 7, 8 and 10 of the Report provide a detailed critique of the

government's carbon tax and its impact on households, the Commonwealth Budget,

the states and, importantly, jobs and investment.

Links to international markets

3.72

Under the carbon tax, emitters cannot buy carbon credits from

international markets for the purpose of offsetting their domestic emissions.

This prohibition will last during the fixed-price period.[60]

At the conclusion of the fixed-price period, an emissions trading scheme will

come into operation. Once the flexible-price period commences and up until

2020, emitters will be restricted to meeting at least half of their annual

liability from domestic permits or credits. This prohibition will be reviewed

by the Climate Change Authority in 2016.

Compensation for affected industries

3.73

Compensation arrangements for affected industries come from two

sources. Measures agreed by the MPCCC and stand alone Government measures.

3.74

Under the carbon tax, '[t]he Government will allocate around 40 per cent

of carbon price revenue to help businesses and support jobs'.[61]

Chapter 5 of the report considers compensation for emissions intensive

industries.

Jobs and Competitiveness Program

3.75

The government has developed a Jobs and Competitiveness Program to

assist industries that are vulnerable under the carbon tax. The Program:

... has been designed to

provide assistance to the most emissions-intensive activities in the economy

that are highly exposed to international competition - either on export markets

or from importers.[62]

3.76

The fund is to provide $9.2 billion over the first three years of the

carbon tax.[63]

3.77

The types of industries that are emissions intensive are those that are

very important to the Australian economy. These industries include coal, steel,

aluminium, food and farming. Together, the mining and agriculture sectors

account for over 70 per cent of Australia’s exports. They are the industries

that build and sustain Australia's prosperity.

3.78

Almost all emissions-intensive and trade exposed activities are in the

manufacturing sector. The Jobs and Competitiveness Program will provide support

to activities that generate 80 per cent of emissions, specifically:

The Government expects that 40 to 50 activities will be

eligible. Examples of eligible activities include aluminium products, steel,

manufacturing, pulp and paper manufacturing, glass making, cement production

and petroleum refining.[64]

3.79

Unfortunately for emissions intensive industries as they confront the

carbon tax, '[f]urther details on eligibility for assistance under the Jobs and

Competitiveness Program will become available in the future'.[65]

This situation is undesirable given that the introduction of the carbon tax is

less than one year away and businesses will need to make employment and

investment decisions prior to and after the possible introduction of the carbon

tax.

3.80

In order to assist the emissions-intensive industries most exposed to

the impact of the carbon tax '[t]he government will allocate, free of charge,

Australian carbon permits to the most emissions-intensive and trade exposed

industries'.[66]

3.81

The Jobs and Competitiveness Program entails two categories of

assistance:

The most

emissions-intensive and trade-exposed activities will initially be eligible for

94.5 per cent shielding from the carbon price. A second category of assistance

will provide an initial shielding level of 66 per cent of the carbon price.[67]

3.82

The table below provides an overview of the cost of the Jobs and

Competitiveness Program.

Table 3.4: Cost of the Jobs Competitiveness Program[68]

|

Year

|

Jobs and Competitiveness

Program ($m)

|

|

2011-12

|

0

|

|

2012-13

|

2,851

|

|

2013-14

|

3,059

|

|

2014-15

|

3,312

|

|

Total

|

9,222

|

The assistance rates will be reduced by 1.3 per cent per year.[69]

Steel industry

3.83

In order to help the steel industry adjust to a lower carbon future:

The Government will provide assistance worth $300 million

over four years to encourage investment and innovation in the Australian steel

manufacturing industry through the Steel Transformation Plan. This will help

the sector transform into an increasingly efficient and economically

sustainable industry in a low-pollution economy.[70]

3.84

A separate government document the Clean Energy Future - Securing a

clean energy future: The Australian Government's Climate Change Plan states

that the $300 million is over five years.[71]

3.85

According to the government, this measure is '... additional to those

agreed by the Multi-Party Climate Change Committee'.[72]

The Steel Transformation Plan is not included as a cost in the government's

Clean Energy Plan released on 10 July 2011 and was not agreed by the MPCCC.[73]

3.86

The Steel Transformation Plan is costed at $189 million over

2011-12 until 2014-15.[74]

Coal industry

3.87

The coal industry is of vital importance to the Australian economy. To

assist the coal industry:

The

$1.3 billion Coal Sector Jobs Package will provide transitional assistance to help the coal industry to implement carbon

abatement technologies for the mines that

produce the most carbon pollution. The amount of carbon pollution produced by

coal mines varies greatly, so the fairest way to deliver assistance is to

target assistance at those mines that are most impacted by the introduction of

the carbon price.[75]

3.88

The Coal Sector Jobs package is $1.3 billion over six years, the cost running

over a four year period starting in 2011-12 is $696 million.[76]

3.89

In addition, this measure will be supported by a '$70 million Coal

Mining Abatement Technology Support Package (which) will provide support for the

development and deployment of technologies to reduce fugitive emissions from

coal mines'.[77]

A total of $70 million is allocated over six years, with the allocation during the

four year period starting 2011-12 being a total of $41 million.[78]

3.90

This measure is '...additional to those agreed by the Multi-Party Climate

Change Committee'.[79]

The Coal Sector Jobs Package and the Coal Mining Abatement Technology Support

Package are not included as costs in the government's Clean Energy Plan

announced on 10 July 2011. Chapter 4 explores the impact of the carbon tax on

the coal industry.

Treatment of heavy on-road

transport

3.91

The government will alter the application of taxation arrangements in

the transport industries. Under the government's plans:

... an effective carbon price on fuel used by heavy on-road

transport from 1July 2014 through changes in fuel tax credits. This will

significantly broaden coverage of the carbon price as heavy on-road vehicles

account for over 25 per cent of road transport emissions.[80]

3.92

The changes to the treatment of heavy on-road transport were not

included as costs in the government's Clean Energy Plan announced on 10 July

2011.[81]

The measure starts in 2014-15 and amounts to $510 million in revenue in its

first year of operation.[82]

Electricity Industry

3.93

The government has also made a commitment to negotiate the closure of

some of the highest emitting coal-fired power stations, representing around

2000 megawatts of generation capacity, by 2020.[83]

No funds are set aside in the Clean Energy Plan for this project, however,

Treasury has advised the committee that these funds will derive from the

budget's contingency reserve.[84]

Chapter 6 explores the issues surrounding the impact of the carbon tax on

Australia's electricity industry.

Revenue and outlays under the carbon tax

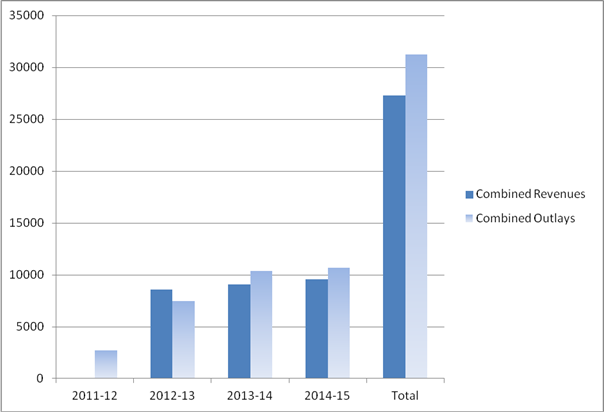

3.94

The table and graph below compare revenues and outlays associated with

the carbon tax agreed within the MPCCC.

Table

3.5: Revenues and outlays under the carbon tax agreed by the

MPCCC[85]

|

Year

|

Combined revenues ($m)

|

Combined outlays

($m)

|

Difference

($m)

|

|

2011-12

|

0

|

2,717

|

-2,717

|

|

2012-13

|

8,600

|

7,490

|

1,110

|

|

2013-14

|

9,080

|

10,366

|

-1,285

|

|

2014-15

|

9,580

|

10,696

|

-1,116

|

|

Total

|

27,260

|

31,269

|

-4,008

|

Note: Numbers may not add due to

rounding, total net impact matches exactly the source for this table.

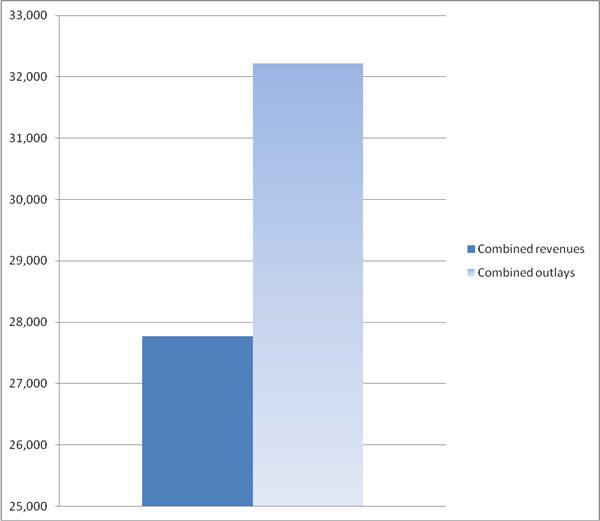

Graphic 3.3 Revenues and

outlays under the carbon tax agreed by the

MPCCC[86]

3.95

Table 3.5 and Graphic 3.3 do not give the full picture of the cost

blow-out of the carbon tax and associated measures. It does not include:

-

$12.8 million for the ACCC;[87]

-

$12 million for advertising and raising community awareness of the

carbon tax and its effect;[88]

-

$41 million for the Coal Mining Abatement Technology Support

Package;[89]

-

$189 million for the Steel Transformation Plan;[90]

and

-

$696 million for the Coal Sector Jobs Package.[91]

3.96

Outlay measures not directly accounted for in the release of the

government's Clean Energy Plan amount to a staggering $950.8 million.

3.97

The government's stand alone measures have increased revenues by

$510 million due to the imposition of an additional fuel tax credit reduction

for heavy on-road transport from 2014-15.

3.98

These same stand alone measures create a deficit of $440.8 million. That

is, the government's measures raise $510 million through the fuel tax credit

reduction and outlay $950.8 million.

3.99

The table and graphic below bring together the combined MPCCC and

government revenues and outlays to highlight a combined deficit of $4449.8 million.

Table 3.6: Total revenues and outlays under the carbon tax

agreed by MPCCC and the government's stand alone measures[92]

|

|

MPCCC and government combined revenues ($m)

|

MPCCC and government combined outlays

($m)

|

Difference ($m)

|

|

Total

|

27,770

|

32,219.8

|

-4,449.8

|

Graphic 3.4 Total revenues and outlays under the carbon tax agreed by MPCCC and

the government's stand alone measures [93]

Committee comment

3.100

It is clear to the committee that the case for a carbon tax has not been

made. The proposed tax is a tax which the Gillard Government promised it would

not introduce.

3.101

Furthermore, the committee considers that the proposed design of the tax,

which will introduce property rights, is highly inappropriate. This feature of

the carbon tax legislation is clearly and deliberately designed to prevent

future governments from implementing a mandate to rescind the carbon tax and

has the potential to expose taxpayers to significant compensation payouts.

3.102

More generally, given the uncertainties surrounding the global framework

for climate change, it could lock Australia into a policy that is both futile

and costly.

3.103

Not only is this particular aspect of the proposed legislation highly

inappropriate but, in addition, the carbon tax package as proposed is fiscally

irresponsible – the introduction of the tax and its associated measures will

result in a cost blow-out of $4,449.8 million. So much for the carbon tax being

'budget neutral' as the Parliament was promised at budget time.

Recommendation 1

It is the Committee's view that the carbon tax should be

opposed and the legislation defeated in the Parliament as:

-

there is no electoral mandate for the carbon tax;

-

the modelling that supports it is based on a number of highly

contestable assumptions;

-

it is likely to undermine Australian businesses' ability to

compete in the global economy;

-

it will have significant adverse effects on particular sectors

and regions, with a particularly disproportionate impact on regional Australia;

-

the effect of the policy on the cost of living, and on jobs is

likely to be higher than the government's current estimates indicate;

-

there is considerable evidence that the carbon tax will not

result in any real environmental gain, despite imposing a significant cost on

the economy over the next thirty years.

The Committee recommends that the

carbon tax be opposed by the Parliament.

Recommendation 2

The Committee recommends that if the Parliament believes

that it should proceed with the carbon tax, any provisions in the legislation

designed to bind future governments seeking to prevent them from amending or

rescinding the scheme be removed.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page