Additional Comments - Senator Andrew Bartlett

I support the recommendations of the Senate Select Committee

on Ministerial Discretion in Migration Matters and agree with the thrust of the

report. I share the concerns raised in the report regarding the lack of

transparency around the ministerial discretion system. The reluctance of DIMIA

and the Minister for Immigration to assist with providing records and other

material pertinent to the Committee's investigation illustrates that the system

is a major accountability problem that all parliamentarians should be concerned

about.

The political genesis of this Inquiry related to specific

allegations against the then Immigration Minister, Philip

Ruddock. Whilst any allegations of serious

impropriety should be examined, the Inquiry demonstrated that the real problems

are with the way the power of ministerial discretion has evolved and expanded

into so many aspects of migration law.

Whilst the current Minister's refusal to allow proper access

to records was frustrating and unacceptable, I believe it must be said that no

solid evidence at all was presented to suggest that the so-called 'cash for

visas' allegations had any real substance. I have been and remain very critical

of many of Minister Ruddock's policies towards migration and refugee issues and

the way those are implemented, but I have seen nothing that leads me to think

that there is likely to be direct corruption of the sort that had been alleged

or implied. Similarly, I have seen nothing which gives weight to any of the

claims against Mr Kirswani,

the member of the public most frequently mentioned in regard to these

allegations.

I believe the 'cash for visas' allegations are a distraction

from the main issue of concern, which is the decline in transparency, independence,

consistency and fairness in the migration area, particularly (but by no means

only) in regard to asylum claims.

I support retaining ministerial discretion, but it needs to

be in a far more limited capacity. I believe the use of the discretionary powers

has grown much larger and wider than is desirable. The Committee's report

details the expansion in the minister's use of these powers in recent years. I

would like to see ministerial discretion restored to it's original intention of

being for unusual and extraordinary circumstances. This would mean reducing

some of the areas where discretion is now available and introducing codified

criteria for visas in areas where discretion has now become commonplace.

I am pleased that the Committee has made recommendations to

this effect, particularly in relation to adopting a system of complementary

protection. However, I would have liked to have seen the Committee present a stronger,

more detailed case for such a measure. I wish here to highlight a number of

options that merit examination in any consideration of implementing a

complementary protection regime in Australia.

The need for Australia

to adopt a complementary protection system

I remain concerned that Australia

is one of the few countries in the developed world that does not have a system

of complementary protection. I believe that the Government is turning a blind

eye to the merits of complementary protection, which are well documented in

evidence to this inquiry. I am left in no doubt that the current Australian

practice of relying solely on ministerial discretion places it at odds with

emerging international trends and that the risks involved in relying solely on

this mechanism are not acceptable.

The Committee has been made aware that most European countries

and Canada have

adopted a visa category which addresses the issue of complementary protection. The

UNHCR advised the Committee that a number of countries have in place

administrative or legislative mechanisms for regularising the stay of persons

who are not formally recognised as refugees, but who are in need of protection

or for whom return is not possible or advisable.[508] Amnesty International also told the

Committee that the international community is in the process of moving towards

developing systems which have a complementary protection component.[509] UNHCR explained recent international

developments regarding complementary protection in the following terms:

Every country has cases which fall in the difficult grey area

between those of people who have experienced high levels of discrimination or

come from countries with recognised human rights concerns, and those of people

who cross the threshold of persecution on convention grounds and are recognised

as refugees. The committee can think of that as a spectrum with people at one

end with no international protection concerns and people at the other end who

are recognised as refugees.[510]

The UNHCR also points out that there are significant

differences in the way countries interpret inclusion criteria set out in

Article 1 of the 1951 Convention.[511]

This means that some persons who are recognised as refugees in one country may

be denied such status in another country. At least three categories of persons

are currently the subject of varying State interpretations of the refugee

definition criteria: those who fear persecution by non-state agents for 1951

Convention reasons; those who flee persecution in areas of on-going conflict;

and those who fear or suffer gender-related persecution.[512]

The reliance of ministerial discretion to meet the

protection needs of those who fall outside of the Refugee Convention’s

definition of a refugee ignores the real dangers facing thousands of people who

seek protection from Australia.

I believe that relying on ministerial discretion in this way

leaves no safeguards to ensure that those whom Australia

has protection obligations under international treaties receive this

protection.[513]

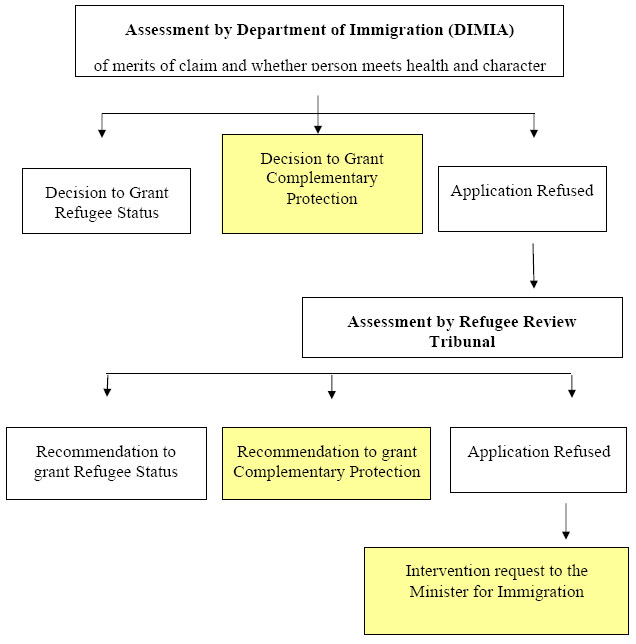

The Refugee Council of Australia has presented the Committee

with a proposal for a model of complementary protection. This model allows decision

makers to grant protection at all stages of the process. As Figure 1 shows, the

model uses a single administrative procedure to determine whether a person is

eligible for complementary protection and is therefore efficient and cost

effective.

I believe this model deserves serious consideration on the

part of the government. Adopting such a model will ensure that Australian

policy is consistent with not only internationally recognised best practice but

also an Australian Government commitment to the framework document Agenda for Protection[514] which was adopted by the

Executive Committee of the UNHCR in September 2001.

Figure 1: Proposed Model of Complementary Protection

(Refugee Council of Australia)

APPLICATION FOR A PROTECTION VISA

The UNHCR also presented a compelling case for the adoption

of a system of complementary protection, one that would overcome some of the problems

that beset the government's current policy towards people who fall outside the

Refugee Convention. The UNHCR told the Committee:

This approach would ensure that key concerns—such as the threat

of torture, the rights of children, or the non-returnability of a stateless

person—are dealt with ... certainty and clarity from the outset, rather than

relying on a non-compellable, non-reviewable executive power at the very end of

the process. UNHCR believes that this is a better risk management and more

humanitarian approach which would avoid prolonged detention and prevent any

chance of people being refouled without these issues being raised and

considered properly.[515]

The UNHCR advised the Committee that in 2002 it had

requested the Government to provide complementary forms of protection to all

Afghans and, more recently, to all Iraqis seeking refugee status ‘because we

know that even rejected Iraqis cannot be returned at present—certainly not in

large numbers’. The UNHCR clarified its position by stating that complementary

protection should only be temporary: ‘We review the situation in principle in

the countries of origin every six months and we brief the government on what

our view is of the situation’.[516] In

addition: ‘For a complementary form of protection, we certainly would not

suggest that the traditional rights that we would request be granted to

convention refugees be applied’.[517]

In other words, the UNHCR is proposing a flexible solution that would be able

to respond to changing circumstances in countries of origin as required.

In addition to the above proposals, there are a number of

other options that should be noted. HREOC advised the Committee that all models

of complementary protection should at the very least incorporate the following

three features:

- clear criteria setting out when a person should

be protected from non-refoulement under the ICCPR, CROC and CAT;

- procedures that protect against errors in

applying that criteria (due process); and

- mechanisms to implement Australia’s protection

obligations for those who meet the criteria (visas).

The CCJDP and the Uniting

Church also advocate the

introduction of a complementary protection scheme into Australian law based on

the various refugee determination systems currently in operation in countries

such as Canada,

the Netherlands,

Sweden, Denmark,

the UK and the US.[518] The Refugee Council of Australia

points out that Denmark

and Sweden have

comprehensive legislation which recognises fully the protection need of certain

groups of people who fall outside the terms of the Refugee Convention, but who

have compelling humanitarian reasons to stay.[519]

The CCJDP argues that the government should seriously

consider two options as a potential solution to the ‘unaccountable’, ‘vague’

and ‘unwieldy’ mechanism embodied in section 417.[520] The first involves the introduction

of a new humanitarian visa class which would have at least two distinct

advantages over the current sole reliance on the section 417 discretionary

powers:

- it would remove the administrative burden,

inconsistency and arbitrary decision making inherent in the section 417 powers

by de-linking the compassionate and humanitarian program from the onshore

refugee program; and

- it would preclude the continuation and use of section

417 in certain circumstances, and increase the discretion available to case

managers and the RRT to deal with more humanitarian claims at a much earlier

stage of the refugee determination process.

The second option would involve amending section 36 of the

Migration Act to give DIMIA case officers and the RRT jurisdiction to grant

protection visas to persons who meet the requirement for protection under the

CAT, CROC and ICCPR. According to the CCJDP, this would enable decision makers

at both the primary and merits review stages to consider relevant human rights

conventions as well as the Refugee Convention, thus ‘improving the criteria for

their discretion, [saving] time, and [reducing] the number of cases currently

made under s417’.[521]

The change would empower decision makers in much the same

way as currently exists for temporary protection visas introduced in 2001.

These visas which apply to those who fall under the umbrella of the Pacific

Solution include criteria that are outside of the Refugee Convention.

I want to also note that DIMIA was unable to substantiate its

claim that introducing special categories of visas will place considerable

pressures on Australia’s

ability to protect its borders, and result in the Minister for Immigration

losing his or her control of the migration determination process. This claim is

simply alarmist and exaggerated. In fact, other witnesses rejected these

arguments outright. Dr Mary

Crock, for example, told the Committee that:

The criteria for the exercise of such powers can be articulated

without opening the floodgates and [government] losing precious control of the

migration process. The criteria are to be found in the human rights enshrined

in international law...[522]

Whilst I remain supportive of the concept of ministerial

discretion, various changes in circumstances and wide-ranging changes to Australia’s

Migration Act have left many thousands of people in a vulnerable position.

Currently we face the prospect of those who were granted temporary protection

remaining in an unprocessed state for months or maybe years to come. The

situation is so dire that those who have argued ministerial discretion adequately

meets these needs can no longer logically do so. The expense, inefficiency and the

human costs of the current system make it absolutely necessary for steps to be

taken to alleviate the problem.

I believe it is time that Australia

accepted and acted upon its international obligations and joined the global

community in offering protection to refugees for non-convention reasons. The

concerns about the flaws and limitations of ministerial discretion have been

raised before Senate Committees many times and outlined in previous reports,

but have not been addressed by government. I therefore strongly urge the

government to accept recommendation 17 of the Committee report and give

priority to implementing a system of complementary protection in Australia.

Andrew Bartlett

Australian Democrats