Chapter 3

Overview of data on Indigenous wellbeing

3.1

This chapter will provide a broad overview of selected data on community

wellbeing, including in areas of health, education, housing and community

infrastructure, juvenile justice, employment and child protection across all

states and territories with regional and remote Indigenous populations. The

committee thought it useful to illustrate broadly some aspects of the wellbeing

of Indigenous populations between both the states and territories in

metropolitan and in regional and remote areas within each jurisdiction are

being measured and reported.

3.2

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) there are two

main types of data useful for evaluation purposes, these are statistical and

administrative collections:

...statistical collections refer to data collected solely for

statistical purposes, such as sample surveys and censuses...[and] administrative

collections refer to data collected in the process of administering or

evaluating a government or community program or service (i.e. the data are a

by-product of an administration process).[1]

3.3

The main source of the data used for this report is the ABS' statistical

and administrative collections as well as other sources such as the Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare and the Ministerial Council on Education, Employment,

Training and Youth Affairs.

3.4

A comprehensive table listing the range of data available on Indigenous

communities was provided to the committee by the ABS and formed the basis of

the table that can be found at Appendix 4 of this report.

3.5

As outlined in its first report, the committee uses the most widely

accepted geographical definition of remoteness which is the Accessibility/Remoteness

Index of Australia (ARIA+). ARIA+ measures the remoteness of a locality based

on the physical road distance to the nearest urban centre and classifies

localities according to the following definitions:

-

major city;

-

inner regional;

-

outer regional;

-

remote; or

-

very remote.[2]

3.6

The committee also wishes to note that data can be interpreted in many

different ways and to suit the purposes of the user. The committee does not

consider the data presented here to be a definitive and absolute picture of

regional and remote Indigenous communities across the states and territories.

Rather the committee intends for the data to present a broad illustration of

the status and wellbeing of regional and remote Indigenous communities.

Issues with current data collections

3.7

During the committee's inquiry a number of submissions and witnesses

presented evidence to the committee on the need for better and more extensive

data collection at both national and state levels.[3] A focus on attaining more

accurate and detailed data would assist in the assessment and monitoring of both

the wellbeing of regional and remote Indigenous communities and the

effectiveness of government policies and service delivery.

3.8

The ABS noted the importance of quality data in its submission, stating

that:

To assess the impact and effectiveness of government policies

on the wellbeing of regional and remote Indigenous communities, high quality evidence

that is comparable over time and across jurisdictions is required. Targets will

only provide motivators for improvement if there is data to show whether or not

they are being met. Good data also provide the broader evidence base for

understanding what interventions might be successful, and in which locations

and situations.[4]

3.9

The committee firmly agrees with the ABS that accurate and relevant data

must provide the evidence base for informing successful policies and to make

progress towards increasing the wellbeing in regional and remote Indigenous

communities.

3.10

The National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction (NCETA)

noted that:

Improved knowledge and understanding of data...is important for

several reasons. It allows benchmarks to be established against which programs

can track progress. It allows goals to be set for improvements and it provides

an empirical basis for the development of targeted interventions.[5]

3.11

The committee also notes that the Commonwealth Minister for Families,

Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, in an address to the

National Press Club, highlighted the Commonwealth government's commitment to

evidence and evaluation, which the committee agrees requires a commitment to

accurate and extensive data collection.

Inevitably there will be difficult decisions but all these

decisions will be driven by one single criterion - evidence. This is the

Government's obsession and we make no excuses for it. It is my abiding fixation

and I readily acknowledge it.

All our policy decision-making will be based on a thorough,

forensic analysis of all the facts and all the evidence. Once implemented, all

programs will be rigorously and regularly evaluated. This is the principle I will

impose across my portfolio.

Spending buckets of money and hoping for the best, does not

work - a point repeated again by Coroner Hope who says in the Kimberley there

have been massive funding allocations with minimal accountability.[6]

3.12

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) also presented

data in its submission to the inquiry which included both administrative and

statistical data. The AIHW noted that the availability, representativeness and quality

of data on the health and wellbeing of Indigenous people in regional and remote

areas is insufficient:

Some surveys are limited by the sample size and therefore the

level disaggregation possible. Other surveys, ask different questions of people

living in remote areas, reducing comparability. For administrative data sets

the issues are more related to differences in the completeness of Indigenous

identification by remoteness—with people living in remote and very remote areas

being more likely to identify as Indigenous than those living in urban areas...Information

on area of residence needed to derive remoteness categories is not available

for many administrative data sources. For example, the juvenile justice and

child protection data sets...cannot be disaggregated by geographical area below a

very broad scale. The lack of specific locational information in some health

and welfare administrative data sets makes it impossible to present information

for Indigenous people by remoteness.[7]

3.13

The ABS in its submission outlined similar concerns to the AIHW.

Increased resources and support, from all levels of

government, for improving identification of Indigenous people in administrative

datasets is essential for the ABS and others to maintain the momentum for

further progress in this area.[8]

3.14

Both the ABS and the AIHW also outlined particular concerns and problems

with the collection of administrative data at the committee's Canberra hearing.

The AIHW outlined some issues with collecting Indigenous data.

Basically our problem with Indigenous data is two-fold.

Usually with survey data, sometimes people who are under survey think across

regions. They can ask the question in urban areas but they change the question

slightly in remote areas, and that makes the data not comparable. Or sometimes

they drop a question completely because they think it is too sensitive in

remote areas and therefore we are not going to ask the question, in which case

we have a gap...

...Our problem is really mostly with administrative data.

Identification level can be variable by state and variable by remoteness.

People in remote areas are more likely to identify as Indigenous...They are still

involved in Indigenous cultural practices and so on. As you move into major

cities this becomes less clear. Therefore it is very difficult when we look at

health status by remoteness for us to separate the fact of identification or

whether there is an actual change in health status between the two areas,

really.[9]

3.15

The ABS noted particular concerns with administrative data collections,

stating that:

When we work with administrative systems we are in the hands

of the people who run those systems. We develop standards and we encourage

people to adopt those standards. Indigenous identification is one of the issues

in an area like criminal justice, but there is actually a paucity of data

across-the-board in many of these areas, particularly where the administration

is primarily with state and territory governments, which quite reasonably set

up independent systems, have different legislative frameworks, and then we have

to try to develop a national framework that fits around that. Our experience is

that that takes a very long time and it does not go as fast as anyone,

including us, would like it to.[10]

3.16

The Commonwealth Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and

Indigenous Affairs, at the 2008 launch of a joint ABS and AIHW report on

Indigenous health, also outlined what the government considers as the current

inadequacies in data collection:

As the authors and drivers of policy we need quality data to

know what works and what doesn't.

But there are glaring gaps in national data collection. For

example this report only contains data on Indigenous deaths from the Northern

Territory, Western Australia, South Australia and Queensland.

This reveals serious gaps in the collection of essential

information including Indigenous mortality. This must be addressed.

The Government knows that if we are to close the gap in

Indigenous disadvantage we must fill in the gaps in data collection.[11]

3.17

The Productivity Commissioner, in a presentation at the ABS NatStats

conference in 2008, noted that improvement of the existing data collections on

births and deaths, hospitals, Medicare, and school enrolment, as well as

addressing the immediate gaps in data on crime victims and perpetrators and

regional data was required to improve the measurement of outcomes for

Indigenous people.[12]

3.18

The committee also notes that extensive gaps in baseline data exist in

relation to the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER). The report of the

NTER review board noted that:

While considerable quantitative and qualitative data is

available in the key areas of health, housing, education, policing and

employment in remote Territory communities, it was clear that little or no baseline

data existed to specifically evaluate the impacts of the NTER.

Apart from some initial scoping data, there was little

evidence of baseline data being gathered in any formal or organised format

which would permit an assessment of the impact and progress of the NTER upon

communities. The lack of empirical data has proved to be a major problem for

this Review and is an area that requires urgent attention.[13]

3.19

The Department of Human Services provided information in their

submission on where income managed funds had been allocated, stating that:

As at 23 January 2009, a total of $133,065,182.70 has been

income managed, of which $130,618.623.34 has been allocated by customers to

various priority items. Food is by far the highest expense incurred by income

managed customers. Representing just under 64 per cent, followed by housing at

9.5 per cent. This is further supported by anecdotal reports of more money

being spent on food, children being well-clothed and fed, houses being

furnished and roadworthy vehicles being purchased.[14]

3.20

At the Canberra public hearing the committee inquired as to how the

department had collected this data and how it had established that the majority

of income managed funds was being spent on food. The department responded:

Ms Gaha—We know that 64 per cent of money has been spent in

shops that primarily sell food. We cannot actually say every single item,

because they also sell clothes...

Senator SIEWERT—Exactly. There are household goods and all

sorts of things.

Ms Gaha—That is correct.

Senator SIEWERT—You do not actually know that 64 per cent has

been spent on food.

Ms Gaha—No. We know that that amount of money has been spent

in shops that primarily sell food.

Mr Tidswell—As the table said, it is the allocated funds.

When we sit down with customers, as you are well aware, we work through to

allocate to their priority needs. That is where that data is taken from.

Senator SIEWERT—That is where that comes from.

Mr Tidswell—Yes. It is not after sale.[15]

3.21

The committee notes that although there is anecdotal evidence to support

an increase in money being spent in shops and retail outlets that sell food, as

well as other approved items, it notes that there is no itemised data available

from the use of the BasicsCard to identify what income managed funds have

actually been spent on. It may not be accurate to say that almost 64 per cent

of income managed funds are being spent on food as there is no system to record

whether this actually occurs. The committee considers that this should be

clarified when the Commonwealth government is reporting on the use of income

managed funds.

3.22

The Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) noted in its submission that

it is 'committed to providing policy advice and implementation of programs

based on the best available evidence'.[16]

The committee notes that DoHA contracted the AIHW to collate and analyse the

data from the NTER Child Health Check Initiative and the AIHW publicly releases

the findings from the data every six months.

3.23

The committee agrees with the NTER Review Board that the quality of data

collection and its use must be given urgent attention and that extensive

consideration must be given to the methodology and process for collecting and

analysing this data. The ABS outlined that high quality data is best obtained:

...when the procedures used are culturally appropriate and

where the Indigenous community is highly engaged in the statistical process.

This is particularly true for remote Indigenous communities. ABS, in its

statistical collection activity, has developed, over a number of years, a

national Indigenous engagement strategy to ensure that Indigenous communities

are better engaged in the statistical process, understand the uses to which the

statistical information is put in developing and evaluating policies that may

impact on them, and have statistical information returned to them in ways in

which they can use it.[17]

3.24

The ABS also cautions against the creation of additional new data

collections suggesting that in order to meet the current requirement for good

expansive data, governments should focus on improving the quality of existing

collections through better 'application of appropriate data management

principles, including the use of agreed definitions and classifications'.[18]

Limiting the number of data collections would also avoid increasing the

respondent load which is very important in Indigenous communities. As the ABS

explained:

Improving the wellbeing of Indigenous Australians is a key

focus for Australian governments. As the demand for evidence to support Indigenous

policy making continues to grow, so does the load placed on the small

Indigenous population by surveys and other research.

There is significant load placed on communities through the

collection of administrative data required as part of, or in support of,

particular service delivery programs. In addition, large-scale, national

surveys such as the ABS collections described in paragraph 9 and surveys commissioned

by other government agencies (state/territory and Australian government), which

generally are not national but can also be quite onerous, add to the respondent

load. However, research in Indigenous communities extends beyond statistical

collections such as national surveys and censuses to include smaller-scale

studies, for example, case studies which may be limited to one or two

Indigenous communities. In an environment of slow change, as the research load on

the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population increases, so does the

likelihood of the Indigenous population becoming disengaged from the data

collection and statistical processes. This impacts on the ability to collect

high quality, relevant information to inform policy and research.[19]

3.25

The committee agrees with the ABS and AIHW that better data collection

and awareness of the importance of quality data is required. The committee also

urges governments to consistently and rigorously familiarise themselves with

available data and be disciplined in utilising the available data when

developing and implementing policies. This was a particular issue highlighted

in the NTER Review Board's report which noted that clearly identifying the size

and composition of the Indigenous population was critical to be able to assess

the NTER's effectiveness and the future resources required to achieve its

objectives. However the NTER did not appear to use the ABS 2006 estimates of

the Indigenous population in the NTER prescribed areas which was estimated at 44

229. The Review board found that internal NTER planning documents cited the

population as 35 929, which according to the Review Board raised 'questions

about the adequacy of the demographic base that has informed the NTER roll-out'.[20]

3.26

The committee is concerned that although quality data from the ABS was

available it was not sufficiently utilised in the development of the NTER

policies. As the ABS noted in its submission:

One of the legislated functions of the ABS (ABS ACT 1975) is

to ensure coordination of the operations of government agencies in the

collection, compilation and dissemination of statistics and related information.

This includes avoiding duplication in information collection, attaining compatibility

between statistics compiled by agencies, and maximising utilisation of

information available for statistical purposes.[21]

The committee is deeply concerned that reliable data was

available from the ABS but it was not used when the measures of the NTER were

being developed.

Recommendation 1

3.27

The committee recommends that COAG make a concerted effort to

improve the quality and scope of existing data collections on regional and

remote Indigenous communities and urges all departments and agencies to

routinely utilise the expertise of dedicated statistical agencies such as the

ABS and AIHW when collecting and analysing data to ensure that it is consistent

and accurate across all jurisdictions.

Undercount of Indigenous

populations in the Census.

3.28

The committee also notes that in its previous report it highlighted

concerns regarding a substantial undercount of the Indigenous population in the

2006 Census.[22]

The ABS advised the committee that they have made reforms and changes that will

more accurately reflect the Indigenous population:

After evaluating the results from the 2006 census, and

particularly undercount for the Northern Territory, WA and Queensland, we have

set up a working group that comprised representatives from state and federal

agencies, local government, various development commissions and Indigenous

organisations to look at the issue surrounding the conduct of the 2006 census.

As a result of that working group we came up with over 30 recommendations on

how we could address some of those issues. Some of those recommendations have

now been included in our plans for the 2011 Census and we will continue to work

closely with that working group in the lead-up to the 2011 census.[23]

3.29

Some of the strategies the ABS are employing for the 2011 Census

include:

-

reducing the overall national under-enumeration rate for the

Indigenous population by reducing the enumeration period for remote

communities;

-

seeking earlier and ongoing engagement with Indigenous groups and

communities and all levels of government;

-

expanding the current Indigenous Community Engagement Program;

-

employment of local engagement managers in areas where the ABS

has had problems with enumeration such as Broome, Fitzroy Crossing, Tennant

Creek and Mount Isa;

-

provision of a greater level of support for Indigenous people in

completing their forms;

-

an expanded public relations campaign;

-

expanding the sample of remote Indigenous communities that are

selected in the post enumeration survey;

-

employment of an additional 300 Indigenous people to provide

assistance to Indigenous households in completing the questionnaires; and

-

establishment of 'flying squads' and mobile teams to travel to areas

where problems have been identified during enumeration.[24]

3.30

The committee will continue to monitor the release of new data

throughout the inquiry and will detail the findings of t

3.31

he new National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey

(NATSISS) which is due to be released in October 2009 in its next report.

Social and demographic context of Indigenous communities

3.32

When comparing the wellbeing of Indigenous communities across the states

and territories, an understanding of the different social and demographic

contexts is important. There are substantial and very important differences

across the states and territories which no doubt influence the way policy is

developed and the method of service delivery.

3.33

Table 1 illustrates the dramatically higher proportion of Indigenous

people that live in the Northern Territory compared to all other states.[25]

For example, 30 per cent of the total population of the Northern Territory are Indigenous

but in all other jurisdictions the overall Indigenous population is less than 4

per cent. This large difference is again repeated when looking only at remote

and very remote populations in each state and territory. In the Northern

Territory 32 per cent of the remote population are Indigenous, compared with

the next highest number in New South Wales at 19 per cent. This is similar to

very remote areas of the Northern Territory where 74 per cent are Indigenous

compared again with the next highest of Queensland and Western Australia at

just under 40 per cent.

Table 1: Demographic

context of indigenous populations by state and territory

|

|

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

SA |

WA |

TAS |

NT |

Aust |

|

%

of population that are Indigenous |

2.24% |

0.65% |

3.54% |

1.79% |

3.45% |

3.76% |

30.39% |

2.50% |

|

%

of population in remote areas that are Indigenous |

19.73% |

2.04%* |

14.66% |

2.65% |

13.11% |

4.91%* |

32.19% |

15.19% |

|

%

of population in very remote areas that are Indigenous |

27.49% |

N/A |

39.80% |

29.07% |

39.27% |

N/A |

74.07% |

47.45% |

Source:

ABS 2002 NATSISS * Includes outer regional and remote areas

3.34

Table 2 presents data from the most recent 2002 NATSISS that

identifies the proportion of Indigenous people in each state and territory that

live on homelands and/or traditional country and who identify with a language

group or clan. Again the Northern Territory has the highest percentage of its

Indigenous population, at 38 per cent, who still live on homelands and/or

traditional country followed by Western Australia with just over 26 per cent and

New South Wales with 23 per cent.

Table 2: Social context of indigenous populations by

state and territory

|

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

SA |

WA |

TAS |

NT |

Aust |

|

% of Indigenous people living

on homelands/ traditional country |

23.8% |

14.9% |

13.4% |

16.1% |

26.4% |

N/A |

38.0% |

21.9% |

Source:

ABS 2002 NATSISS

3.35

Table 3 below shows the percentage of the Indigenous population

identifying with a tribal group or language group or clan in remote and

non-remote areas in New South Wales, South Australia, Western Australia,

Queensland and the Northern Territory. The table illustrates that New South

Wales has the lowest percentage of Indigenous people identifying with a tribal

group or language group or clan. The Northern Territory has the highest

percentage of the population identifying with a tribal group or language group

or clan, at almost 95 per cent in remote areas, followed by South Australia,

remote areas in Western Australia and Queensland.

Table

3: Identification with tribal group or language group/clan

|

NSW |

QLD |

SA |

WA |

NT |

Aust |

|

Remote |

45.3% |

65.4% |

77.6% |

68.7% |

94.3% |

76.6% |

|

Non-remote |

41.5% |

53.0% |

58.8% |

40.8% |

41.5% |

45.7% |

|

Total |

41.7% |

56.2% |

63.3% |

53.8% |

88.4% |

54.1% |

Source: ABS 2002 NATSISS

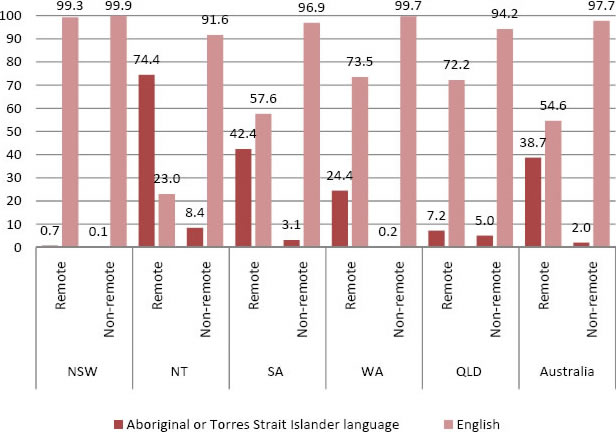

3.36

Another significant area of difference between the states and

territories in the social and demographic context is the percentage of

Indigenous people who do not speak English as the main language at home, as

illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Primary language spoken at home

Source: ABS 2002 NATSISS

3.37

In New South Wales less than one per cent of Indigenous people in both

remote and non-remote areas speak an Indigenous language as the main language

at home, whereas in the Northern Territory almost three-quarters of Indigenous

people speak an Indigenous language at home followed next by remote areas of

South Australia with 42 per cent and Western Australia with just under

one-quarter. Most of the other states also have sizeable differences between

remote and non-remote areas except for New South Wales and Queensland where

there is no significant statistical difference between the two populations.

3.38

Overall, this broad outline of some of the main data on the demographic

and social context of Indigenous communities indicates that the Northern

Territory has the largest remote Indigenous populations with the highest level

of Indigenous language speakers and people living on homelands or traditional country.

The committee notes that when developing and implementing policies and

delivering services to Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory the

government would face greater logistical challenges and costs than many of the

other jurisdictions.

General wellbeing in regional and remote Indigenous communities

3.39

The 2002 NATSISS and the 2004-05 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS) collected data on the general, social and

emotional wellbeing of Indigenous communities including personal stressors,

community issues, mental health, cultural identification and racism. The AIHW

also reports on the wellbeing of Indigenous people including data on 'health,

health determinants, welfare, access to housing and/or homelessness services,

aged care and other services'.[26]

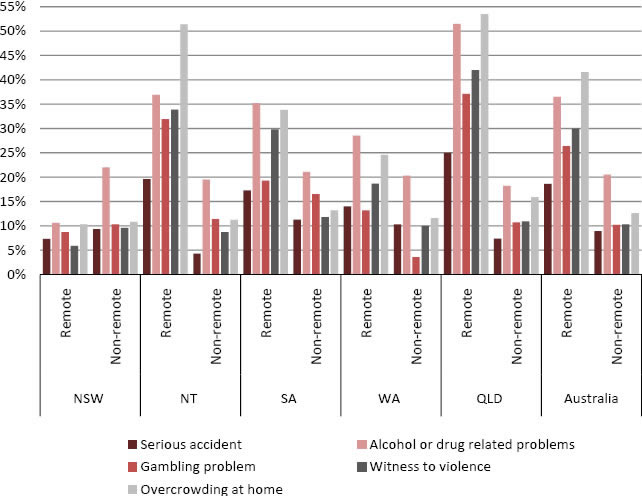

3.40

Figure 2 over the page illustrates some differences between states and

territories in relation to the types of personal stressors experienced in the

last 12 months by Indigenous people in remote and non-remote areas.

3.41

The types of stressors reported by respondents differ significantly

according to remoteness. Figure 2 illustrates that Indigenous adults who lived

in remote areas in the Northern Territory, South Australia, Western Australia

and Queensland were significantly more likely than other Indigenous adults to

say that they had been a witness to violence, had a gambling problem, and/or

had been involved in a serious accident. Remote areas in Queensland recorded

the highest reported stressors across all five listed in the graph with over 50

per cent of respondents reporting overcrowding and alcohol or drug related

problems as personal stressors followed with the next highest percentages in

the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia respectively.

Only in New South Wales did a non-remote area report a higher instance of one

of the stressors, that being alcohol or drug related problems, otherwise all

other stressors were more prominent in remote areas.

3.42

The AIHW notes that the higher incidence of Indigenous people living in

remote or very remote areas reporting stressors than those in major cities is most

likely to be related to socioeconomic and environmental disadvantage:

...for example, 2% of Indigenous houses are community rental housing

in major cities compared with 55% in remote Australia, and more Indigenous

clients received support for homelessness in regional and remote areas than in

major cities.[27]

Figure

2: Type(s) of personal

stressors experienced in last 12 months

Source: ABS 2002 NATSISS

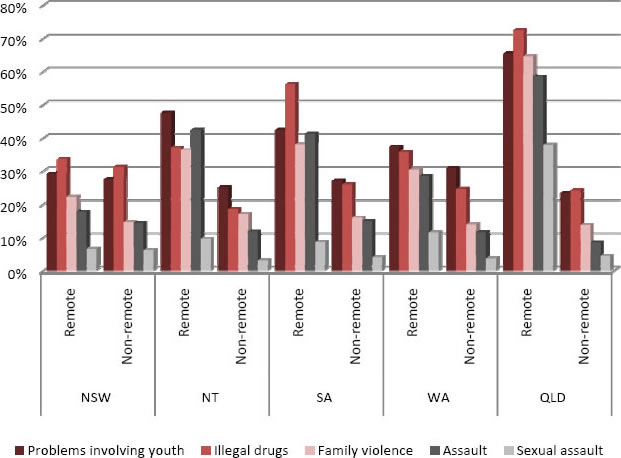

3.43

The NATSISS also surveyed the percentage of the Indigenous population

over 15 years of age that reported neighbourhood and community problems in both

remote and non-remote areas. The graph below illustrates a small section of the

responses which again differ across jurisdictions. In New South Wales there was

very little difference between remote and non-remote areas however in

Queensland the difference is quite distinct with all of these reported in

higher numbers in remote areas. The remote areas of Queensland reported the

highest levels of all these community problems, with almost 40 per cent of

respondents reporting sexual assault as a problem in remote areas of Queensland

with the next highest in the Northern Territory at just under 10 per cent. Over

50 per cent of respondents reported that illegal drugs were a concern in remote

Queensland and South Australia.

3.44

Also evident is the high rate of reported community and neighbourhood

problems involving young people. Apart from remote areas of New South Wales,

where it was just under 30 per cent, in all other jurisdictions over 30 per

cent of respondents reported that young people were causing problems in the

community, with remote Northern Territory reporting almost 50 per cent and remote

Queensland again the highest at over 60 per cent.

Figure 3: Neighbourhood/community problems

reported, 2002

Source:

ABS 2002 NATSISS

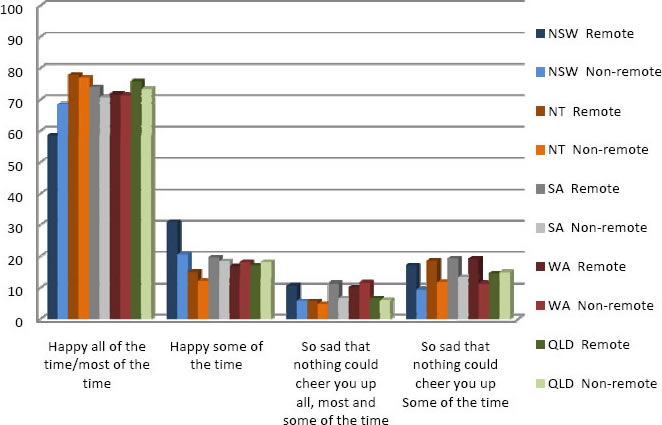

3.45

A similar result is also illustrated in the graph over the page which is

a selection of positive wellbeing indicators taken from the most recent

NATSIHS. Apart from New South Wales at least 70 per cent of respondents in the

other states and territories were happy all or most of the time but more New

South Wales respondents in remote areas reported being happy some of the time.

The overall level of happiness reported in Indigenous communities was for the

most part similar across the states and territories.

3.46

On the other hand Figure 4 below also provides data on sadness, with almost

10 per cent of respondents in remote areas of New South Wales and South

Australia as well as both the remote and non-remote areas in Western Australia

being so sad that nothing could cheer them up all or most of the time. Almost

20 per cent of respondents in remote New South Wales, Northern Territory, South

Australia and Western Australia recorded being so sad that nothing could cheer them

some of the time. However again, overall there was no sizeable difference

across the states and territories in positive wellbeing even though many of the

contributing factors—such as housing, safety and education—can differ

significantly in the same areas.

Figure 4: Selected indicators of positive wellbeing, by

remoteness, 2004-05

Source:

ABS 2004-05 NATSIHS

3.47

The committee also notes the lack of data on the characteristics of

Indigenous carers and their wellbeing. When asked at the committee's hearing in

Canberra whether the AIHW was aware of any data on carers in Indigenous

communities looking after the elderly population and people with disabilities,

the AIHW responded:

We are not aware of anything specific in relation to

Indigenous carers. We are doing some further work on carers at the moment,

basically off administrative data sets for our biennial publication Australia’s

Welfare, which has not been published yet but may well have come up with

further information. At this stage there is nothing further that we could

suggest.[28]

3.48

The committee finds this lack of data and a seeming lack of any plans to

improve this data concerning and urges the Commonwealth government to consider

improving data collection in this area.

Housing and community infrastructure

3.49

There is comparable data on housing and community infrastructure that

again illustrates sizeable differences between the states and territories.

3.50

The data illustrated here in Table 4 identifies that the Northern

Territory has both the highest number of Indigenous people living in an

overcrowded household and in a dwelling with major structural problems. For

example in the Northern Territory only 39 per cent of Indigenous people live in

a dwelling with no major structural problems whereas all other jurisdictions

record that almost 60 per cent of Indigenous people live in a dwelling with no

major structural problems. Overcrowding in the Northern Territory is three

times greater than the national average and more than twice the rate of

overcrowding in the state with the next highest rate, which is Western

Australia.

Table 4: Indigenous

housing, 2004-05

|

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

SA |

WA |

TAS |

NT |

Aust |

|

% of Indigenous

people Living in a dwelling with no major structural problems |

64.3% |

62.3% |

64.3% |

59.9% |

59.2% |

73.5% |

39.5% |

60.4% |

|

% of Indigenous

households that were overcrowded in 2006 |

9.0% |

8.3% |

13.6% |

10.7% |

14.2% |

6.7% |

33.7% |

12.4% |

Source: ABS 2004-05 NATSIHS

3.51

In regards to houses being connected to essential infrastructure, the

AIHW's report on Indigenous housing indicators 2005-06 found that:

The majority of discrete Indigenous communities in Australia

were connected to an organised supply of water (99%), sewerage (98%) and

electricity (97%). The Northern Territory had the largest number of communities

not connected to an organised supply of these services, with seven not connected

to water or sewerage and 20 not connected to electricity.[29]

3.52

The Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report noted that data on access

to clean water and functional sewerage needs to be collected on a regular basis

to allow 'comparison between services in Indigenous communities and those delivered

by major utilities'.[30]

3.53

The committee notes that although all states and territories need to

focus on improving Indigenous housing there is a clear deficiency in the

standard and availability of Indigenous housing in the Northern Territory when

compared to the other jurisdictions with significant remote and very remote

Indigenous populations. The committee notes that current Commonwealth and

Northern Territory policy is focused on alleviating some of this housing

distress by the selection of 15 out of the 26 priority communities earmarked

for new housing being in the Northern Territory. This is discussed in more

detail in Chapter 4.

3.54

The levels of community infrastructure and services provided in Indigenous

communities also differ greatly between states and territories. As previously

noted, the Northern Territory has the poorest housing figures, yet in some

areas of access to community infrastructure it records some of the more

positive outcomes. For example, as Figure 5 illustrates, the Northern Territory

has the highest proportion of its Indigenous population in discrete Indigenous

communities with a women's shelter and, along with Queensland, the highest

recorded percentage for swimming pools.

3.55

The data presented in Figure 5 below suggests that access to youth

centres is low across all jurisdictions with only Queensland having more than

50 per cent of its population of discrete Indigenous communities with access to

youth centres. All the other jurisdictions all recorded less than 30 per cent.

The lack of access to youth centres as well as other youth programs in remote

Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory in particular is supported by

the Central Australian Youth Link Up Service's outline in their submission on

the infrastructure needs in the Central Australian region of the Northern

Territory.[31]

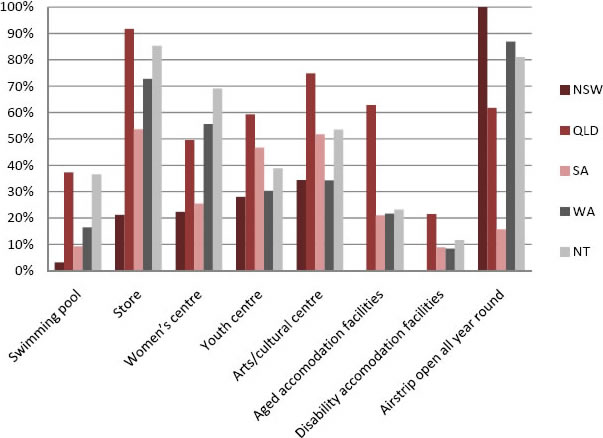

Figure 5: Proportion of reported usual population of discrete Indigenous

communities with access to facilities, 2006

Source: AIHW 2008 Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Health Performance Framework report

3.56

The committee also notes that Figure 5 illustrates that New South Wales

recorded the lowest proportions across all four selected categories, recording

almost half the availability/existence of community infrastructure of

Queensland. For example New South Wales has no aged or disability accommodation

facilities in its discrete Indigenous communities. All other states, apart from

South Australia, also registered a very low proportion of access to both aged

facilities and to disability accommodation facilities, with no state or

territory recording more than 20 per cent of the reported usual population in

discrete Indigenous communities having access to disability accommodation

facilities.

3.57

The committee is concerned that the data indicates very low access to

aged facilities and disability accommodation facilities in all jurisdictions in

discrete Indigenous communities. Such facilities, as well as other respite

facilities, are very important in any community in a regional or remote area.

The committee discusses this further in relation to the NTER, and will pursue

further investigations into aged care support and facilities in its remaining

reports.

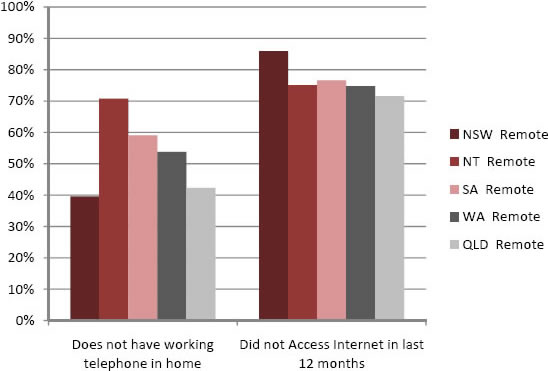

Figure 6: Indigenous

access to telephone and internet in remote areas

Source:

ABS 2002 NATSISS

3.58

Figure 6 above depicts access to telephones and the internet in remote

areas across the states and territories. Access to the internet was

comparatively limited across all jurisdictions with at least 70 per cent of

people not using the internet in the last 12 months. However with telephone

access in the home results were much more varied, with just over 70 per cent of

Indigenous people in remote areas of the Northern Territory not having access

to a telephone in their own home, compared to 40 per cent in New South Wales.

Clearly a greater focus is required in bridging the 'digital divide' in

regional and remote Indigenous communities.

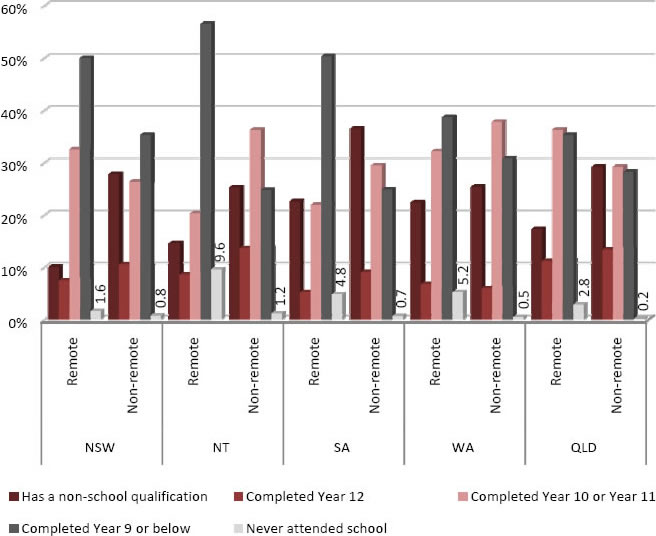

Indigenous educational attainment and standards

3.59

In the area of education the data again illustrates large differences

between the standards of reported Indigenous attainment levels across the

jurisdictions. The graph below outlines the educational attainment of

Indigenous people aged over 15 years that were surveyed in the NATSISS. From

this graph the highest proportion of Indigenous people who have never attended

school live in remote areas of the Northern Territory, almost 10 per cent,

followed by remote areas of Western Australia, South Australia, Queensland and

finally New South Wales with 1.6 per cent. Across all jurisdictions the number

of people who never attended school was much lower in non-remote areas.

Figure 7: Level of educational attainment of Indigenous

persons aged 15 years or over, 2002

Source:

ABS 2002 NATSISS

3.60

Figure 7 above also shows that remote areas in New South Wales have the

lowest percentage of Indigenous people with non-school qualifications at just

below 10 per cent. Only the remote areas of South Australia and Western

Australia registered more than 20 per cent of Indigenous persons aged over 15

with a non-school qualification.

3.61

NCETA notes in its submission that:

Potential factors contributing to the low levels of

Indigenous students’ school retention rates include availability and

accessibility of schools, especially secondary schools, racism at school,

parents’ negative experiences of schooling, wellbeing of the children (poor

health, hunger, hearing difficulties, substance abuse), and the perceived

quality and relevance of available schooling.[32]

3.62

The National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) test is

another recent addition to nationally comparable data collections on

educational achievement that specifically identifies Indigenous students and

geographical locations. The committee notes the Council of Australian Governments

(COAG) has stated that the results of the NAPLAN tests will be used as performance

indicators by the COAG Reform Council to measure progress against the Closing

the Gap target to 'halve the gap for Indigenous students in reading, writing

and numeracy within a decade'.[33]

3.63

The most recent tests for which results have been released were

conducted in May 2008 for Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 across Australia. This was the

first time all students in the same year level have been assessed on the same

test items across reading, writing, language conventions (spelling, grammar and

punctuation) and numeracy in all states and territories. The Ministerial

Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA) in the

report on the results of the 2008 NAPLAN tests stated that:

The tests broadly reflect the curriculum content across all

States and Territories, and the types of test questions and test formats were

chosen so that they would be familiar to teachers and students.

NAPLAN is an important innovation in national literacy and

numeracy assessment in Australia. It reports the full range of student

achievement against a common scale and uses a common set of tests to resolve

the technical difficulties associated with equating State and Territory based

tests.[34]

3.64

The NAPLAN results show that overall at all year levels Indigenous

students were less likely to be achieving at or above the national minimum

standards than non-Indigenous students. The report notes that across year

levels:

...there is a decline in the difference between Indigenous and

non-Indigenous student mean scores for Reading, Spelling, Grammar and Punctuation,

but there is an increase in the differences for Writing. The differences in

Numeracy are the same at each year level. The participation rate for Indigenous

students declines as year level increases.[35]

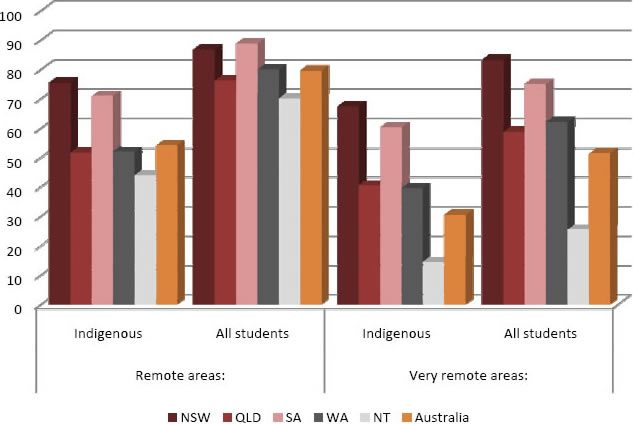

3.65

The committee has outlined in this report the reading and numeracy

results for Years 3 and 7 across all jurisdictions with remote and very remote

populations. The results from the NAPLAN for these areas are illustrated

Figures 8-11 on the following pages.

3.66

For the year 3 results in reading, remote and very remote areas in New

South Wales and South Australia had the highest percentages of Indigenous

students at or above national minimum standard, at around 70 per cent in remote

areas and 60 per cent in very remote areas. However, in very remote areas in

Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory less than 40 per cent

of Indigenous students were at or above national minimum standard, with the

Northern Territory scoring around 14 per cent. Again in numeracy New South

Wales and South Australia performed the best out of all jurisdictions in remote

areas while in very remote areas only the Northern Territory recorded less than

50 per cent of students at or above national minimum standard.

3.67

Figure 9 illustrates reading achievements for Year 7 students. The

committee notes the very low percentage of Indigenous students that are at or

above the benchmark in very remote areas in South Australia and the Northern

Territory. In South Australia only 17 per cent were at or above the benchmark

and in the Northern Territory it was just under 14 per cent. The Northern

Territory government has previously acknowledged the need to improve Indigenous

literary and numeracy skills in a 2008 policy document:

The ability to read and write and to be numerate is the

foundation for all school learning. Good literacy and numeracy skills are critical

if young people are to complete their schooling successfully. These skills are

also required if they are to participate fully in the economic and social

development of the NT and the nation.

Despite substantial investment by the NT and Australian

governments in supporting the improvement of literacy and numeracy skills for students,

and the genuine effort of Department of Education and Training (DET) staff over

many years to improve results, there has been no significant improvement in NT

students ‘ literacy and numeracy outcomes.[36]

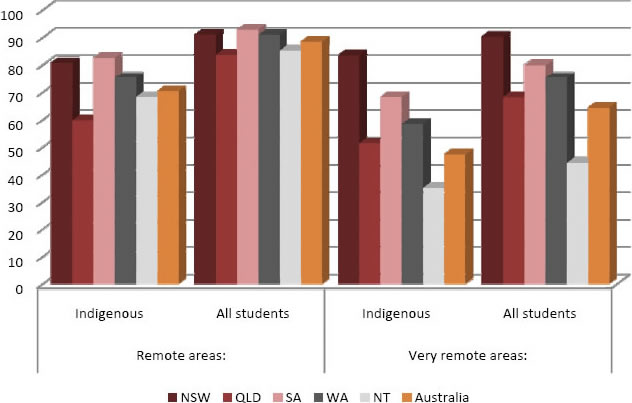

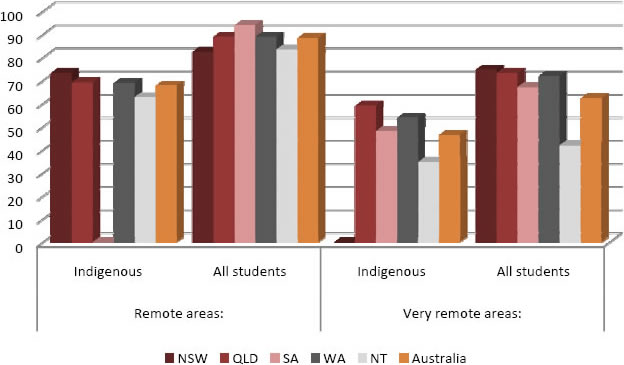

Figure 8: Percentage of Year 3 students at or above national

minimum standard in reading, 2008

Figure 9: Percentage of Year 3 students at or above national minimum standard

in numeracy, 2008

Source:

MCEETYA 2008 NAPLAN

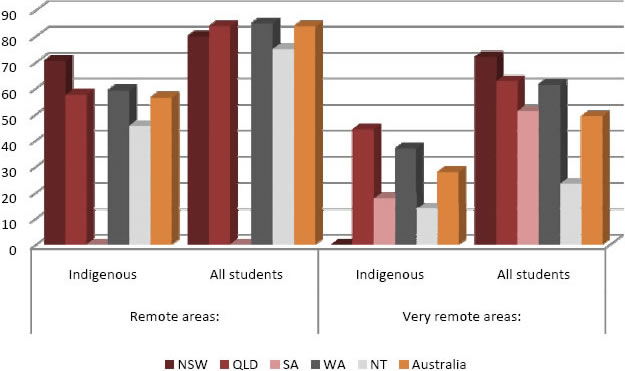

Figure 10: Percentage of Year 7 students at or above national minimum standard in

reading, 2008

Note: Where there are no

results this indicates that the data was not published as there were no

students tested or the number of students tested was less than 30.

Figure 11: Percentage of Year 7 students at or

above national minimum standard in numeracy, 2008

Source: MCEETYA 2008 NAPLAN

3.68

The MCEETYA report noted that the Year 7 results for reading and

numeracy showed that:

In the Northern Territory, Indigenous students are

one-quarter to one-third as likely to be achieving at or above national minimum

standards in literacy domains and half as likely to be achieving at or above

national minimum standard in Numeracy...

...the mean score for Indigenous students [across Australia] is

substantially lower than that for non-Indigenous students, and is cause for

major concern. In Reading, for example, the difference in the means across

Australia is 74 points, the difference in the Northern Territory is 145 points

and in Western Australia it is 83 points.[37]

3.69

In addition to student attainment, student attendance levels are another

area of interest to the committee for comparison across the states and

territories. The MCEETYA National Report on Schooling in Australia 2007

outlined the data on comparable school attendance across the jurisdictions for

full time students in Years 1-10. The report noted that school attendance was 'a

new performance measure and currently student attendance data is not collected

uniformly across jurisdictions and schooling sectors'.[38]

The report also noted that:

...due to variance in the systems in place for collecting

student attendance data across the sectors and jurisdictions it is not yet

possible to collect the data consistently across Australia in all

jurisdictions/sectors.[39]

3.70

Figure 12 over the page depicts the attendance rates for government

schools but the MCEETYA report did not disaggregate the data by remoteness area

and did not list any source of such disaggregated data in the statistical

annex.

3.71

The committee considers this is a priority area as the COAG National

Indigenous Reform Agreement has identified national, jurisdictional and

geo-locational—the school's geographical location—school attendance rates as

one of the two performance indicators to be used to measure progress against

the Closing the Gap target to 'Halve the gap for Indigenous students in Year 12

attainment or equivalent attainment rates by 2020'.[40]

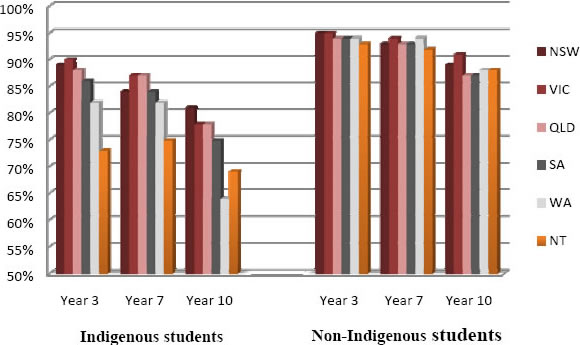

Figure 12: Student attendance rates in government schools in

2007

Source: MCEETYA

2009 National Report on Schooling in Australia 2007

3.72

In general, student attendance in Victoria, Tasmania and New South Wales

tended to be higher than the other jurisdictions. The Northern Territory

attendance rates were lower than those of other states for each year level. The

Northern Territory had the lowest levels of attendance in all years for

Indigenous students except in year 10 where Western Australia was slightly

lower at just under 65 per cent compared to the Northern Territory's 68 per

cent. The MCEETYA reported noted that the data indicated that:

...Indigenous students attended school at lower rates than

non-Indigenous students, with the variation in attendance more pronounced in

the later years of schooling. For some States and Territories, there was a

difference of more than ten percentage points in attendance rates between

Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. In the Northern Territory, particularly

from years 6 to 10, the difference was close to 20 percentage points.[41]

3.73

The committee notes that the Northern Territory Department of Education

and Training has published its own school attendance data, which is provide

below in Table 5, but this is not comparable to other jurisdictions. The

committee acknowledges the particular logistical difficulties faced by the

Northern Territory government with a high proportion of its Indigenous

population residing in remote and very remote areas. However the committee is

concerned that this data suggests that very little progress has been made since

2008.

Table 5: School

attendance in the Northern Territory 2008-09

|

|

2008 |

2009 |

|

Geolocation |

Indigenous |

Non-Indigenous |

Total |

Indigenous |

Non-Indigenous |

Total |

|

Provincial |

81.1% |

90.6% |

88.7% |

82.6% |

91.9% |

90.1% |

|

Remote |

81.9% |

92.4% |

87.7% |

82.5% |

92.7% |

88.0% |

|

Very

Remote |

65.7% |

91.0% |

69.1% |

63.5% |

90.1% |

67.0% |

Source:

Northern Territory Department of Education and Training - Enrolments and

attendance 2008-2009

The health of the Indigenous population

3.74

The AIHW report Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance

Framework 2008 report analyses data on the comparative state and territory

government expenditure on health goods and services for Indigenous people. The

report noted that the Northern Territory ($5,461) and South Australia ($4,011)

had the highest average expenditure per person for Indigenous people. As Figure

13 below depicts, the increased expenditure is related to the proportion of the

Indigenous population that reside in remote and very remote areas.

Figure 13: Expenditure ratio on Indigenous health

Source: AIHW

2008

3.75

The committee notes that there is no universally collected primary

healthcare data currently available. At the committee's hearing in Canberra on

9 June 2009 the committee asked the AIHW if there was anything being done to

address this vacuum:

Generally in terms of primary healthcare data it is a

difficult area to get data on. We have, say, seven million hospital separations

a year that we collect data on but a great many more are primary care episodes.

Filtering out and trying to get a useful data collection out of that is an

interesting problem. A few months back we published a report towards primary

healthcare data looking at what existing data there is because there are

various electronic collections that do collect data. It is certainly something

that we are hoping to do further work on. I think the Primary Healthcare

Strategy will be a key document from which data collection will be launched

because that overall policy will be clear about what needs to be collected. It

is really a case of what should be collected. We are doing some work at the

moment with the states and territories on trying to develop a national minimum

dataset, that is the minimum number of standard items that should be collected

in relation to primary healthcare and community health. We are certainly trying

to take it forward.[42]

3.76

In terms of other basic health indicators available, the 2004-05 NATSIHS

collected various data on Indigenous health in regional and remote Indigenous

communities including information on general health, smoking, alcohol

consumption, long term health conditions, oral health, Body Mass Index,

immunisation and women's health issues.

3.77

The committee notes that very little data is currently available about

the patterns and levels of alcohol and drug use by Indigenous people,

especially amongst young Indigenous people. NCETA noted in its submission that

it has undertaken investigation of data that examines the pattern of alcohol

and drug use by school aged children. The study found that

Indigenous students were 1.27 times more likely to have used

any illicit drug in the last year compared to non-Indigenous students (with

age, gender, school type (Government, Catholic, Independent), self-rated

academic performance, alcohol and tobacco use, socio-economic disadvantage, and

language spoken at home controlled for).

The most commonly used illicit drugs among Indigenous students

were cannabis, inhalants, and tranquillisers.[43]

3.78

The NCETA noted that very little of the available data has been

published and is currently preparing documents that report these findings. The

committee looks forward to the release of additional data on the patters of

alcohol and drug use of young people and would also like to see the data

reported by geographical location and on a state and territory level.

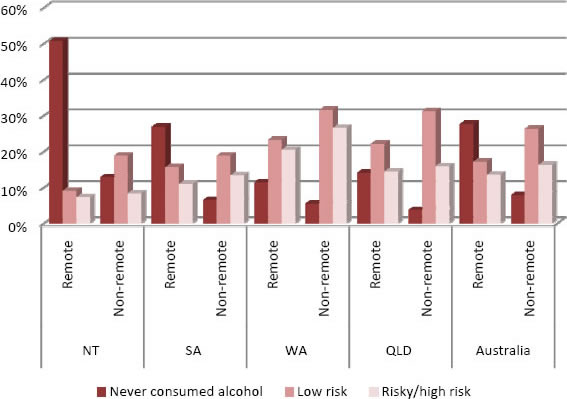

Figure 14: Alcohol risk of Indigenous persons aged 18 years

and over, 2004-05

Source: ABS 2004-05

NATSIHS

3.79

Figure 14 above illustrates the alcohol risk of Indigenous people across

states and territories and in both remote and non-remote areas. Of particular

interest is that 50 per cent of Indigenous people in remote areas of the

Northern Territory reported having never consumed alcohol which was far above

any other jurisdictions either remote or non-remote. Overall a higher proportion

of Indigenous people in remote areas had never consumed alcohol than in

non-remote areas across all jurisdictions and there was less reported low risk,

risky and high risk drinking in remote areas as well.

3.80

The committee also notes the data available on Indigenous health workers

and the numbers of medical practitioners. As discussed in Chapter 5, the number

of Aboriginal Health Workers (AHW) has been declining in some states and

territories recently. This is also supported by data analysed by the AIHW which

is illustrated over the page in Figure 15. As the graph shows, from 2001–2006

the number of male AHWs increased in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland

but decreased in the Northern Territory and Western Australia. For female AHWs,

numbers in New South Wales and Queensland increased by over 20 per cent in South

Australia and the Northern Territory, slightly increased in the Northern

Territory and South Australia but decreased in Western Australia.

Figure 15: Male AHWs by state and territory, 1996, 2001 and

2006, Census.

Figure 16: Female AHWs by state and territory, 1996, 2001 and

2006, Census.

Source: AIHW 2009

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health labour force statistics and data

quality assessment.

3.81

In Figure 17 below, apart from New South Wales all remote areas had a

lower reported daily consumption of fruit and vegetables than non-remote areas,

with daily fruit consumption the lowest in remote Western Australia and vegetable

consumption the lowest in the Northern Territory.

Figure 17: Selected dietary habits of Indigenous persons

aged 12 years and over, 2004-05

Source: ABS 2004-05 NATSIHS

Table 6: No. of

psychiatric beds in public acute hospitals with psychiatric units per 100 000 people, 2004-05

|

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

SA |

WA |

TAS |

NT |

Aust |

|

Inner regional |

12.9 |

11.7 |

22.7 |

0 |

5.8 |

20.1 |

N/A |

14.4 |

|

Outer regional |

0.4 |

4.7 |

16.4 |

0 |

14.7 |

0 |

23.8 |

9.3 |

|

Remote |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6.6 |

1.2 |

|

Total all regions (including

major cities) |

13.3 |

18.1 |

23.4 |

11.2 |

20.9 |

17.8 |

16.0 |

17.2 |

Source:

AIHW (2007) Mental health services in Australia 2004-05

3.82

In terms of mental health, the AIHW released a comprehensive report on mental

health services in Australia in April 2007. The aim of the report was to

provide information on a wide range of mental health-related services provided

in Australia, as well as the resources associated with those services. Although

the report is not Indigenous-specific it does provide information on mental

health facilities available by remoteness area as Table 6 above illustrates.

Only the Northern Territory has public psychiatric beds available in remote

areas and it also has the most available per 100 000 people in outer regional

areas. The committee was surprised to note that South Australia has no beds

available in outer regional or remote areas.

Employment

3.83

The ABS 2002 NATSISS also collected data on the size of the Indigenous

labour force and the difficulties Indigenous people have finding employment.

Figure 18 below outlines the percentage of Indigenous people not in the labour

force by state and territory and remoteness. Remote areas of the Northern

Territory recorded the highest percentages, just on 50 per cent, followed by

the remote areas of New South Wales and the non-remote areas of Western

Australia and South Australia respectively. In Queensland, South Australia and

Western Australia the percentage of Indigenous people not in the labour force

was greater, even if only slightly, in non-remote areas than in remote areas.

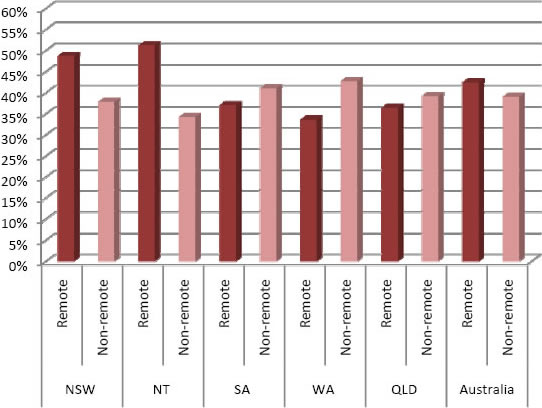

Figure

18: Percentage of Indigenous persons aged 15 years or over not in the labour

force, 2002

Source: ABS 2002 NATSISS

3.84

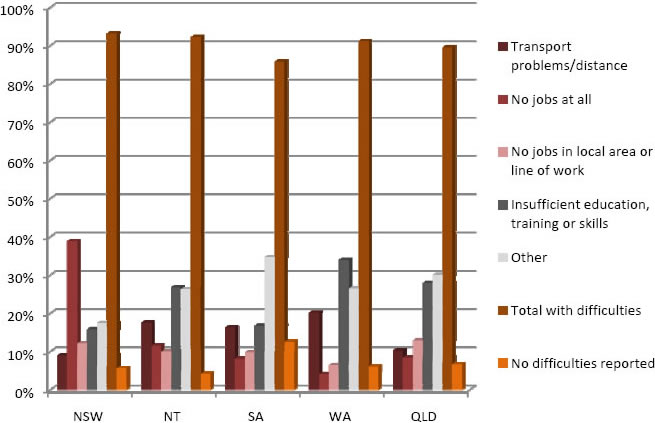

Figure 19 over the page illustrates that over 80 per cent of unemployed

Indigenous people in remote areas find it difficult to find work, rising to

over 90 per cent in New South Wales where the most common barrier to finding

work is that there are no jobs at all. However in the Northern Territory and

Western Australia the greatest barrier is insufficient education, training or

skills to find a job and this reason is second only to no jobs in local area or

line of work in Queensland.

3.85

NCETA notes in its submission that:

Employment status and employment opportunities are key

factors in the health and wellbeing of individuals and the communities in which

they live. Employment status and opportunities are also heavily implicated in

the risk of problematic alcohol and other drug use. So, from a prevention perspective,

the need to ensure that adequate employment options exist is of fundamental importance.[44]

Figure 19: Main difficulty finding work for unemployed

Indigenous persons aged 15 years or over in remote areas, 2002

Source:

ABS 2002 NATSISS

3.86

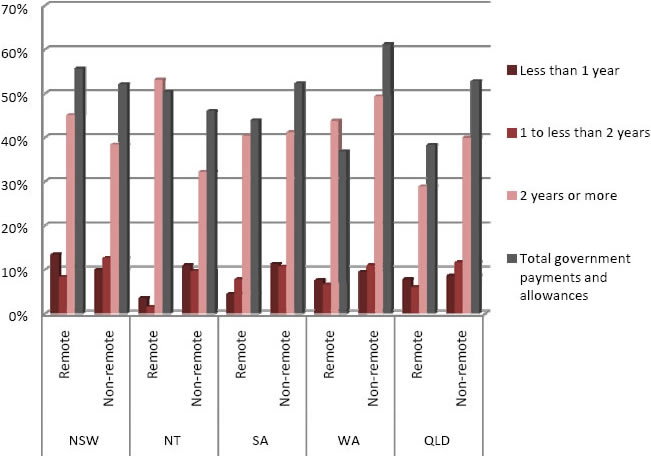

Figure 20 over the page outlines the percentage of the total Indigenous

population in remote and non-remote areas for which government pensions and

allowances have been the main source of income. The majority of Indigenous

people have been on government pensions and allowances for more than two years

with a higher percentage of Indigenous people in Western Australia and

Queensland in non-remote areas on government pensions and allowances than in

remote areas. In remote areas in the Northern Territory and South Australia

fewer than 5 per cent have been on government pensions and allowances for less

than one year whereas in New South Wales is more than double that number at

13.5 per cent. Also of interest is that overall the Northern Territory has a

smaller percentage of Indigenous people in remote and non-remote areas on government

pensions and allowances than New South Wales.

Figure 20: Times

that government pensions and allowances have been the main source of income in the

last 2 years for Indigenous people aged 15 years and over, 2002

Source:

ABS 2002 NATSISS

Welfare and security of children and young people

3.87

The committee is unable to compare data on juvenile justice and child

protection across states and territories in regional and remote areas. This is

because, as the AIHW noted in its submission, :

...data on young people in juvenile justice facilities or under

juvenile justice supervision can be disaggregated by state and territories but

cannot be disaggregated by geographical location. The same is the case for

children in the child protection system where the child protection data set

does not allow for the reporting of the data by region or remoteness.[45]

3.88

The committee was particularly concerned with the limited data available

in this area given that at the time of arrest and incarceration details on

where the offence was committed and where the person resided would be recorded.

The committee is also concerned with the lack of detailed data in this area

given that juvenile detention rates are one of the 12 Headline Indicators for

the Productivity Commission's annual Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report.[46]

3.89

Although geographical regions within jurisdictions cannot be compared,

the more general differences between states and territories can. The AIHW

report on Juvenile justice in Australia 2006-07 identifies that while

rates of juvenile justice supervision:

...for non-Indigenous young people were similar across all

states and territories, there was considerable variation in the rates for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people. Western Australia had the

highest Indigenous rate, with around 80 per 1,000 Indigenous young people under

supervision, followed by South Australia with 50 per 1,000...the Northern

Territory, Tasmania and Victoria had the lowest rates, which ranged from 20 to

26 per 1,000.[47]

3.90

The report also notes that both Western Australia and Tasmania have had

large increases in the rate of Indigenous people under supervision. In Western

Australia, the rate of Indigenous young people under juvenile justice

supervision:

...increased from 70 per 1,000 in 2003–04 to 80 per 1,000 in

2006–07...In contrast, the Indigenous rate decreased in South Australia from 62

to 50 per 1,000.[48]

3.91

The report outlines the average daily number of young people in

detention by Indigenous status in each state and territory. On a daily average

almost 90 percent of young people in detention in the Northern Territory are

Indigenous followed by Western Australia with just over 70 per cent. It is also

clearly evident that a further disaggregation of this data into remoteness

areas would provide valuable information and allow better comparison between

states with large urban populations and those with relatively large remote

populations.

Table 7: Average

daily number of young people in detention 2006-07

|

NSW |

QLD |

WA |

SA |

NT |

Aust |

|

Indigenous |

184 |

91 |

83 |

21 |

26 |

443 |

|

Total all young

people |

386 |

145 |

117 |

52 |

29 |

941 |

|

% that are

Indigenous |

48% |

63% |

71% |

40% |

90% |

47% |

Source: AIHW 2008

3.92

The committee's research has shown that there are similar problems with

data collections related to child protection. The most recent Overcoming

Indigenous Disadvantage report noted that existing data collections needed to

be developed to:

...better reflect the underlying extent of child protection

issues that are not necessarily apparent from administrative data on substantiations,

notifications and orders.[49]

3.93

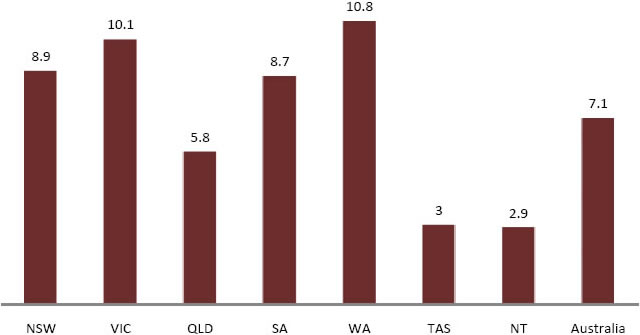

Figure 21 below illustrates the number of Indigenous children on care

and protection orders in each state and territory, which differs greatly. It

should also be noted that even though the Northern Territory has a low ratio it

does not necessarily give a complete picture as it may also indicate a lack of

services in remote and very remote areas where a substantial proportion of the

Indigenous population reside.

Figure 21: Ratio of Indigenous to non-Indigenous children on

care and protection orders, July 2007

Source: AIHW 2008

3.94

The AIHW's report Child protection Australia 2006–07 also lists

the type of abuse or neglect that is reported by state and territory. There are

many notable differences, for example in Western Australia, 50 per cent of the

notifications are for neglect while in Queensland it is 33 per cent and in

Victoria it is 19 per cent. In addition South Australia only has 2.7 per cent

of notifications for sexual abuse while Western Australia has 12.5 and the

Northern Territory has almost 10 per cent. The Northern Territory and Victoria

have by far the highest notifications for physical abuse with just over 30 per

cent with the next closest at 22 per cent.

3.95

The comparisons with non-Indigenous children are also interesting as

although Indigenous children across all jurisdictions have a higher percentage

of notifications for neglect and for emotional abuse, excluding Queensland,

while non-Indigenous children, with the exception of the ACT and Tasmania (for

which the data should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of

Indigenous children), have a higher percentage of notifications for sexual and

physical abuse. It also must be noted that there may be substantial

under-reporting of child abuse across all jurisdictions.

Figure 22: Percentage of children aged 0-17 years who were the subject of

substantiated notifications: type

of abuse or neglect, by Indigenous status and state/territory, 2006-07

Source: AIHW 2008

3.96

The committee notes that the Australian Institute of Family Studies, in

its submission, outlined that:

A simple examination of the statistics showing an

over-representation of Indigenous children and young people in the child

protection and out-of-home care systems does not answer why this occurs. Such

correlational data need to be examined in detail to see whether there is

something inherent in Indigenous populations, in the policies and procedures of

authorities (such as overt or covert racism, which may mean that problems in

Indigenous families are more likely to be observed and come to the attention of

authorities), or whether such overrepresentation can be explained by some other

underlying causes (e.g., socio-economic disadvantage).[50]

Conclusions from the data

3.97

Throughout the broad examination of some basic data on areas related to

the terms of reference for the committee's inquiry, such as health, welfare,

wellbeing, child protection and employment, what becomes obvious is the great

difference between the status and wellbeing of Indigenous people across the

country. It also provides some additional quantitative evidence to substantiate

the constant pleas the committee receives from witnesses that there can be no

one-size-fits-all solution as there is no one consistent problem across jurisdictions

or communities.[51]

This was also acknowledged recently by the Commonwealth Minister for Families,

Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs in an address to the

National Press Club:

The Government realises that there is no single solution to

what is a systemic, complex problem. It just doesn't make sense to think that

what works in one remote Indigenous community can be effectively transposed to

another. This has to be tackled community by community, with local input and

ownership.[52]

3.98

Providing an overview of some of the available data also illustrates the

importance of good data collection and analysis for developing policy and

assessing the needs of people who live in particular areas. Using accurate and

relevant data specific to the location of the intended area of implementation

is essential, as situations and needs can vary between remote and very remote

areas as well as in regional areas. The committee notes that more work on

improving data collection that can be disaggregated to regional locations and

by remoteness areas needs to be undertaken.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page