Chapter 4 - Factors influencing the demand for housing

4.1

There are a number of factors which have driven up the demand for

housing, and in particular for home ownership, in recent years.

Higher incomes

4.2

As Australia has lifted its productivity, and benefited from the

higher prices for its commodity exports due to the 'resources boom', average

incomes and household wealth have increased.[1]

It is unsurprising that households have wanted to spend some of this increased

income and wealth on improving the quality of their housing. At the upper end

there has also been increased demand for second 'holiday' homes, particularly

in coastal regions.[2]

To the extent that supply responses are limited (see next chapter), this

increased demand leads to higher prices.[3]

4.3

For many couples, household incomes are higher because both

partners now work (as indicated by rising labour force participation rates).

However, as Professor Julian Disney notes:

By fuelling competitive bidding-up of house prices it has led

many couples into taking on excessive workloads to pay their mortgage.[4]

4.4

Incomes have increased at a similar pace across most income

quintiles in the past decade.[5]

But there are likely to be some groups whose capacity to save and bid for homes

has improved less than others. For example, around 300 000 people have accumulated

HECS/HELP debt, which may be an impediment to buying a home.[6]

Demographics

4.5

The average household size has decreased for a number of reasons,

such as later marriage, fewer children and increased incidence of separation

and divorce.[7]

This increases the demand for housing for a given population. Demographic

projections are for this to continue, with lone person households expected to

increase at a much faster rate than family and group households.[8]

4.6

Australia has relatively strong population growth for an advanced

economy. A large component of this reflects relatively high immigration

compared to comparable countries. Higher immigration rates have added to demand

for housing, especially as immigrants tend to be disproportionately young

adults.[9]

Immigrants have also tended to head for areas where housing is already short,

such as Sydney, rather than to country regions. This partly reflects a

perception of where the best job opportunities are located. It has a self-reinforcing

aspect as new arrivals prefer to locate in areas where friends or relatives

have already gone or where there are shops and cultural facilities catering to

people from their ethnic background.

4.7

An eminent demographer points out that:

About half the growth in households in Melbourne is attributable

to overseas migration. When you push out the 30-year projection, as you get

near the end of it, about 80 per cent of the growth is attributable to

migration...in Sydney, all the growth in households is attributable to overseas

migration.[10]

4.8

This has led some witnesses to suggest restricting immigration,

even of skilled workers, as a means of curbing rises in house prices:

One of the key drivers of the housing crisis, we believe, is the

continued rapid population growth in Australia, which is a continent of very

low carrying capacity, and most of the development is around the edges of the

continent...[we recommend] that we train our own skilled workers and that we

cease poaching skilled workers from other countries.[11]

4.9

In this context, the committee also notes concerns that in the

current environment of skill shortages in the construction industry, the net

impact of immigration is inflationary:

We do not have the trades to build the housing stock that we

need. Immigration into the country is fuelling demand at a much faster rate

than immigration is helping our industry build that extra demand.[12]

4.10

There are also alternative arguments:

I am all for increasing immigration....I think that, to support

infrastructure in this country with the landmass we have, we need a lot more

people to use those facilities.[13]

4.11

The Government has made it clear it sees substantial net economic

benefits from continued high rates of immigration:

The Australian labour market is the tightest it has been in a

generation, with skill and labour shortages pushing up labour costs and

contributing to inflationary pressures. Immigration will continue to be an

important contributor to labour supply, with skilled migration in particular

helping to address Australia's skill needs in the short-term while also

delivering fiscal benefits.[14]

4.12

The committee regards population growth policy as an important

issue, but one outside the terms of reference of this inquiry.

4.13

The relationship between the overall number of skilled migrant

workers and the number with particular skills in the construction industry is

discussed in more detail in chapter 5 (paragraphs 5.60–5.64).

High rents

4.14

The increase in rents in recent years has increased the desire

of many renters to buy a home instead of renting. However, having to pay higher

rents has reduced the ability of these households to save a deposit. The

net impact on the effective demand for house purchases is therefore ambiguous.

Lower interest rates

4.15

The decline in the standard home loan interest rates from the mid–1990s

to early 2002 increased the amount that households could borrow and so gave

them the ability to bid up house prices. For example, the repayments on a 30–year

mortgage of $100 000 at an interest rate of 14 per cent are $1185 per month.

When interest rates are instead 7 per cent, the same repayments can service a

loan of $178 000.

4.16

The main reason for the drop in housing loan interest rates had

been the lowering of the Reserve Bank's policy interest rate as a low inflation

environment has become established. But increased competition has also seen a

reduction in the margin between the policy interest rate and the housing loan

rate.

4.17

If this mechanism were the only driver of prices, then prices

would have fallen back again as interest rates have since risen. However, there

may be inertia in the system, or prices may be 'sticky', as vendors are

reluctant to accept low bids. This would imply that affordability will only be

restored by the gradual rise in incomes rather than a fall in nominal house prices.

4.18

Given that underlying inflation has recently risen above the

Reserve Bank's 2‑3 per cent medium-term target band, it could be argued

that aggregate demand in the economy has been allowed to grow faster than

aggregate supply. A loose fiscal and/or monetary policy is likely to result in

rises in asset prices, including house prices, as well as generalised

inflationary pressures.

4.19

When the Reserve Bank Governor was asked what the central bank

could do about housing affordability he replied:

the best thing that we can do is keep inflation rates

controlled, because if we do not do that then interest rates will end up much

higher than otherwise. I think the biggest problem for housing affordability is

that basically, particularly if you are a first home buyer, the level of house

prices is too high. The policies to address that are mainly not in our

preserve, except that, if we run monetary policy too loose, house prices tend

to inflate more than they need to and that would not be good.[15]

4.20

The committee received comment from one submitter who criticised

the Reserve Bank's approach to monetary policy. Mr Phil Williams highlighted in

his submission that the RBA's inflation target is set solely in terms of consumer

prices, not asset prices. The cost of land is not included in the CPI.

As a result, Mr Williams argued that the RBA's monetary policy failed to

respond to the sharp spike in house prices in 2002–2003.[16]

He claimed that the underlying cause of house price inflation is the conduct of

monetary policy which should aim for house price stability, not just the 2–3

per cent CPI band.[17]

4.21

The committee does note that the RBA has been vigilant in seeking

to restrain the CPI to within its target band. There have been several

increases in the official cash rate over the past three years which 'is helping

to produce a moderation in demand'.[18]

Table 4.1: Housing

finance markets

|

|

Typical term of mortgage

(years) |

Typical loan-to-value ratio

for new mortgages (%) |

Variable rate mortgages (%

of total) |

Owner-occupiers with

mortgage (% of total) |

Home equity with-drawals |

Mortgage market index# |

Use of mortgage-backed

securities |

|

Australia

|

25 |

80 |

85 |

45 |

yes |

0.69 |

extensive |

|

Austria

|

25 |

60 |

|

|

no |

0.31 |

|

|

Belgium

|

20 |

83 |

25 |

56 |

no |

0.34 |

limited |

|

Canada

|

25 |

75 |

30 |

54 |

yes |

0.57 |

extensive |

|

Denmark

|

30 |

80 |

32 |

|

yes |

0.82 |

no |

|

France

|

15 |

75 |

20 |

38 |

no |

0.23 |

limited |

|

Germany

|

25 |

70 |

30 |

|

no |

0.28 |

yes |

|

Hong Kong

|

20 |

70* |

most |

|

|

|

yes |

|

Ireland

|

20 |

70 |

most |

|

limited |

0.39 |

limited |

|

Japan

|

25 |

80 |

21 |

|

no |

0.39 |

limited |

|

Netherlands

|

30 |

90 |

26 |

85 |

yes |

0.71 |

extensive |

|

NZ

|

25-30 |

95 |

16 |

|

|

|

limited |

|

Norway

|

17 |

70 |

most |

|

yes |

0.59 |

no |

|

Singapore

|

30-35* |

80* |

most |

|

|

|

yes |

|

S. Korea

|

20* |

56 |

most |

|

yes |

|

limited |

|

Sweden

|

25 |

80 |

98 |

|

yes |

0.66 |

limited |

|

Switzerland

|

15-20 |

80* |

35 |

|

no |

|

limited |

|

UK

|

25 |

75 |

97 |

60 |

yes |

0.58 |

yes |

|

USA

|

30 |

80 |

22 |

65 |

yes |

0.98 |

extensive |

*maximum # IMF (2008) measure: higher values

indicates easier household access to mortgage credit. Sources: BIS (2006, pp

12–4); Ellis (2006, p. 14); IMF (2008); Lawson and

Milligan (2007, p.46); Tsatsoranis and Zhu (2004, p. 69); Zhu (2006, p. 60).

Greater credit availability

4.22

In addition to interest rates being lower, loans have become

easier to obtain. In the longer term this has been a welcome result of

financial deregulation. Non-bank lenders have increased the availability of

credit for housing, tapping into securitisation markets. Since deregulation,

the Australian housing finance market has developed a wide range of products

and credit is available to all potential borrowers who can afford the

repayments (Table 4.1).

4.23

In this brave new financial world, banks no longer 'ration'

credit only to customers with a long record of placing money in low-interest

deposit accounts with them. As the Reserve Bank's deputy governor noted:

...if you go back just 30 years it was very hard for households to

get access to finance. Basically, to get a housing loan you had to save for

years at the bank and then you had to plead with the bank to give you some

money and then they only gave you some of the money. You had to go to a finance

company, a building society or someone else and borrow at much higher rates to

get the rest of the money to buy a house...and if you were a woman you had no

chance.[19]

4.24

Looking back further, the increase in the availability of credit

is even starker.

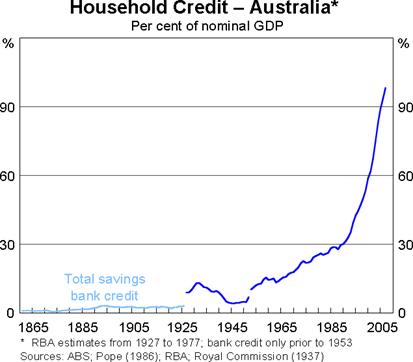

Chart 4.1

Source: Battellino (2007).

4.25

However, there is evidence that recently credit standards have

been loosened excessively. This was been most noticeable in the United States

where the prevalence of 'sub-prime' loans is now causing serious problems in

financial markets. While Australian lenders have not gone as far as their

counterparts in the US, the Reserve Bank has referred to 'the general lowering

of credit standards that has occurred since the mid 1990s' and the Australian

Prudential Regulation Authority has referred to lenders having 'been willing to

move out the risk spectrum by loosening their credit standards'.[20]

4.26

Housing lenders are now much more likely to allow customers to

borrow amounts that require more than 30 per cent of income to service and will

lend a higher proportion of the value of a property.[21]

There is considerable variation among lenders in how much they will lend, as

noted by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority: 'The most aggressive ADI

will typically be willing to lend more than twice as much as the most

conservative'.[22]

4.27

There are disadvantages in moving away from the old model where

banks required people to save a deposit with them before granting a loan. As Dr

Judith Yates commented: 'having a savings history is not a bad idea in that it

indicates that people do have the capacity to save'.[23]

Households unable to save regularly may struggle to meet loan repayments.

4.28

The greater availability of credit has fuelled the aspirations of

first home buyers. A Queensland developer gave this example:

When we first started developing land out there [Ipswich], in

1992, we noticed that people would buy a block of land and spend probably the

next 12 months building their house. They would spend every weekend out in the

front yard landscaping, doing all those things that they could not afford to do

when they first built the house. It probably took them almost two years to come

up with a house in the form that they actually wanted. Now we do not see any of

that. Now we see people shifting into a house with everything done up-front—swimming

pool, landscaping, everything. My point is: I think people want everything

straightaway these days.[24]

4.29

As lenders moved from rationing credit to marketing it, some

households were offered larger amounts of credit than they could readily repay:

Deregulation of the financial institutions in the eighties had a

significant impact on low-income people. Not only do those people sign up for

things they cannot afford but also they often do not understand the paperwork

they are signing.[25]

4.30

A similar view was put by John Symond of Aussie Home Loans:

money has been too free. Instead of looking at getting their

ultimate home step-by-step, young people expect and want a new home with all

the mod cons. They go off to a department store and borrow $20,000 for a plasma

TV, new lounges and everything else in the belief that it is interest-free and

the latest and the greatest. They then find out that they have been stung with

a 28 per cent interest rate. So clearly credit tightening would be a good

thing.[26]

4.31

Regretting some of the excesses associated with financial

deregulation might be regarded as wishing the stable door had been shut before

the horse had bolted. But the committee did hear some suggestions for some mild

forms of regulation to address these concerns:

Options for consideration may include mandatory minimum credit

checks, minimum loan-to-value ratios for property purchases, restrictions on

advertising targeting persons with a poor credit history, or public disclosure

of the level of credit risk held or on-sold by lending institutions.[27]

Speculative demand

4.32

In addition to the demand from people wanting a house in which to

live, there is a speculative element to the demand for housing. As one witness

put it, 'houses are being valued as speculative assets, not as homes for

Australians anymore'.[28]

(See the discussion in Chapter 2 on 'changing aspirations').

4.33

As well as encouraging home ownership, this attitude has led many

households to borrow to purchase a second investment property.[29]

Investors now account for about a third of new home loans. The Reserve Bank

(2003, p. 48) has referred to the role of unregulated property investment

seminars in promoting the purchase of investment properties.

4.34

Except for the brief period of 'irrational exuberance' about hi‑tech

stocks around 2000, Australians have generally regarded property as a better

investment destination than equities, although they are less attracted to it

now than in the 1980s.

4.35

There is a self-reinforcing aspect to speculative booms:

Related to this boom period is the self-generating nature of

house price rises. Most finance for housing arises from the high price already

of existing housing, because people upgrading build on the increased value of

their housing, and investors are then drawn in by rising prices. So you have a

self-generating effect until they hit something like much higher interest rates

or a recession or something.[30]

Chart 4.2

Source: Reserve Bank (2003, p.

41)

Taxation influences

4.36

This speculative demand for housing may be encouraged by some

aspects of the taxation system, which makes investing in housing (and sometimes

other assets yielding capital gains) more attractive than alternative

investments. A blunt assessment is provided by Professor Julian Disney:

...a major cause of our problems is that we have excessive

exemptions for owner-occupiers from capital gains tax, land tax and the pension

assets test. They are so generous that they have driven up housing prices. They

have ended up being not in favour of homeownership; they are in favour of

current homeowners but they are not in favour of homeownership.[31]

4.37

In similar vein, the economics journalist Ross Gittins has

commented:

Do you see what the special tax-free status of housing does? By

pushing up the price of homes it makes it that much harder to attain the state

of being a home owner, but makes the benefits of home ownership even greater if

you manage to make it. The jackpot's bigger, but harder to win. And a system

that is biased in favour of owner-occupiers is a system that is biased against

renters. That's unfair to people who spend all their lives as renters, as well

as making it harder for would-be home owners to make the leap.[32]

4.38

Significant tax concessions are currently provided for housing.

It is not easy to find hard data on the costs of most of these concessions[33],

but the secretariat has put together in Table 4.2 some approximate numbers from

the sources indicated, based on the assumptions listed. In addition to the tax

expenditures listed, the exemption of owner-occupied housing from the asset

test for the age pension costs around $10 billion.[34]

4.39

The combined total of capital gains tax arrangements, land tax

exemption and negative gearing arrangements is estimated to be in the order of

$50 billion per year. That reflects against the $1½ billion in the

Commonwealth–State Housing Agreement and the $1 billion spread over four to

five years proposed for the new National Rental Affordability Scheme and the

Housing Affordability Fund. These tax concessions also mean that the overall

support to wealthy homeowners is greater than that to low income renters.[35]

Table 4.2: Taxation expenditures pertaining to housing ($

billion in 2007-08)

|

Capital gains tax exemption for

owner-occupied housing[36]

|

20 |

|

Discount on capital gains on

investor housing[37]

|

6 |

|

Land tax exemption for

owner-occupied housing[38]

|

10 |

|

Negative gearing for rental

housing[39]

|

2 |

|

Non-taxation of imputed rent

for owner-occupied housing[40]

|

15 |

Sources: Secretariat estimates,

see footnotes.

Table 4.3:

International comparison of taxation regimes

|

|

Interest tax deductibility |

Capital gains tax |

Land tax |

Investor |

Tax on imputed |

Indirect tax rate |

|

|

Owner |

Investor |

Owner |

Investor |

Owner |

Investor |

Negative gearing |

Depreciation |

rent |

on new houses (%) |

|

Australia

|

no |

yes |

no |

half rate |

no |

yes |

yes |

yes* |

no |

10 |

|

Canada

|

no |

yes |

no |

half rate |

yes |

yes |

yes* |

yes |

|

|

|

France

|

no |

yes |

no |

no* |

limited |

limited |

limited |

yes |

no |

20 |

|

Germany

|

no |

no |

no* |

no* |

limited |

limited |

yes |

yes |

no |

16 |

|

Neth'nds

|

yes |

na |

na |

na |

yes |

yes |

na |

no |

yes* |

19 |

|

NZ

|

no |

yes |

no |

no |

limited |

limited |

yes |

yes |

no |

0 |

|

Sweden

|

yes |

yes |

limited |

limited |

yes |

yes |

yes |

no |

|

|

|

Switz.

|

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

no |

yes* |

yes |

|

|

UK

|

no |

no |

limited |

yes |

limited |

yes |

yes |

no |

no |

0 |

|

USA

|

yes |

yes |

no |

yes |

yes |

yes |

limited |

yes |

no |

|

Sources: Ellis (2006, p.

11); Lawson and Milligan (2007, p.46). *under some conditions

4.40

The tax treatment of housing in Australia is compared with that

in comparable countries in the above table.

Recommendation 4.1

4.41

In the interests of more informed discussion of arrangements to

encourage affordable housing, the Treasury be asked to publish current

estimates of various taxation and related measures affecting the housing

market.

Discount on capital gains on

investor housing

4.42

Capital gains on investor housing held for over a year are taxed

at half the marginal tax rate applied to other income.[41]

A common argument for this discount is that it also applies to holdings of

shares.[42]

Some would contend that the logic of not discriminating between different types

of income would mean that all capital gains should be taxed at the same rate as

other income. (In some tax regimes, capital gains are regarded as 'unearned

income' and taxed at a higher rate than other income.) The current

arrangements do not apply to alternative investments, such as bank deposits

(and education and training), which generate income that is not in the form of

capital gains.

4.43

A number of witnesses argued that capital gains should be taxed

like other income. Apart from fairness concerns, it was argued that the concession

encourages investors to focus on investment in that type of housing where

capital gains are expected to be largest and this may be more expensive rather

than affordable housing:

...we should not have the discount on capital gains tax, because

it is crucial that we do not encourage investment to go where the capital gain

is the greatest. We need it to go to the bottom end.[43]

4.44

Another suggestion was that the concession be more focused:

Australians would be better served if the incentives were based

entirely on newly constructed houses rather than established houses so it led

to an increase in supply.[44]

4.45

In contrast, the construction industry argues that the tax rate

on capital gains should be lowered further:

...governments need to introduce a stepped-rate capital gains tax

where after, say, 10 years there is no capital gains tax applicable. This will

mean you will get investment into the rental market.[45]

Capital gains tax exemption for

owner-occupied housing

4.46

Capital gains on owner-occupied housing (the 'family home') are

exempt from income tax. This is another aspect of the taxation system which

favours housing as an asset class and increases demand for it.

4.47

Master Builders Australia argue that the exemption should be

retained, on the grounds that:

There is no empirical evidence to support the proposition that

the tax exempt status of home ownership undermines the equity or efficiency of

the tax system.[46]

4.48

Others witnesses expressed reservations. Professor Sorensen

commented:

...the tax breaks afforded to housing—for example, the absence of

capital gains tax for owner-occupied housing...just simply tend to feed in to

higher prices for housing.[47]

4.49

The exemption may also lead to households demanding larger homes

than they require at the time for accommodation, to increase their prospective

capital gains:

Owner-occupiers were encouraged to over-invest in housing

producing the so-called 'McMansions' in the outer suburbs. This was, in part, a

logical response to the fact that capital gains are not paid on the family

home. The family home was thus seen by middle income households as an

opportunity to maximise their savings.[48]

4.50

Another fault with this tax concession is its regressive nature:

...the capital gains tax exemption for owner-occupied housing is

vastly regressive in a social sense, with nearly all the gain from that

exemption going to high-income households.[49]

Land tax exemption for

owner-occupied housing

4.51

All states, and the ACT, impose land taxes but exempt almost all

owner‑occupied housing (Table 7.6). This impacts on what in principle

would be an efficient and equitable tax and can encourage some people to hold

wealth in the form of housing in excess of their requirements for

accommodation.[50]

4.52

Shelter WA recommends capping this exemption to a level 10 per

cent above the median house price for the region.[51]

4.53

A problem in taxing the land value of owner-occupied housing is

that asset‑rich but income-poor households, such as retirees, may need to

incur debt to pay it. This is easier to do now that 'reverse mortgages' are

more readily available, but older households are likely to be wary of

increasing their debt. Professor Disney suggests addressing this problem by

making the land tax at least partially deferrable until sale.[52]

Negative gearing

4.54

'Negative gearing' refers to allowing investors to deduct losses

on rental property from their other income (not just other property income) and

so lower their tax liabilities. In aggregate, landlords received gross rental

income of $19 billion in 2005–06, from which they were allowed to deduct $14 billion

in interest, $1 billion in capital works deductions and $9 billion of other

deductions (including letting agents' fees, body corporate levies and council

rates), giving an overall 'loss' of $5 billion which they could offset against

other income.[53]

4.55

Included among the deductions is a depreciation allowance of 2½

per cent on new buildings. This had been introduced at 4 per cent in 1985 when

the scope of negative gearing was reduced by quarantining the interest cost

offset to rental income.[54]

The rate was lowered to 2½ per cent in 1987 when the quarantining was removed

and full negative gearing restored. It could be argued that houses are an

appreciating rather than depreciating asset, or that 2½ per cent overstates any

physical depreciation (ie that the average house will last more than forty

years).

4.56

Negative gearing is criticised on equity grounds:

We have argued that it is iniquitous. It is not spread fairly

and it really represents one of the starkest contrasts in the Australian

taxation system.[55]

4.57

This leads to suggestions to cap it.

...there should be caps. There should not be unlimited access.

Millionaires and billionaires should not be able to access it, and you should

not be able to access it on your 20th investment property. There should be

limits to it.[56]

4.58

Master Builders Australia defend negative gearing as 'part of a

modern tax system'.[57]

Table 4.3 shows that tax systems in a number of modern economies do not allow,

or restrict, negative gearing.

4.59

The Real Estate Institute of Tasmania claimed that 60 per cent of

those using negative gearing 'are your mum and dad investors—normal

Australians—not the rich and wealthy'.[58]

While investors owning rental properties may be 'normal', they may also be more

affluent than the average taxpayer.

4.60

A number of witnesses point out, correctly, that negative gearing

also applies to other investments such as purchases of shares.[59]

However negative gearing seems to be used a lot more for housing than for

investment in other assets, with some recent estimates suggesting that a third

of investors in housing claim they are making losses. In many cases, when the

rental property is initially bought, the investor expects to make such a loss

but hopes that (concessionally taxed) capital gains will mean the undertaking becomes

profitable. As noted above, in Australia housing investors routinely make an

aggregate loss, while in other countries they generally make an aggregate

profit.[60]

4.61

The most common argument by supporters of negative gearing (and

capital gains tax concessions) is that it increases the supply of rental

accommodation and keeps rents lower than they otherwise might be.[61]

FaHCSIA stated that 'the taxation provision for negative gearing has

demonstrably increased the amount of rental housing that is available in the

broader market', but under later questioning, acknowledged that 'we do not have

any information from our own sources' to support this and made references to

work by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.[62]

4.62

It does seem to be the case that rental yields (ie rent as a

proportion of the property price) on their own could be unattractive without

the tax advantages. A common rule of thumb in the Australian real estate market

is that a property that costs X thousand dollars will rent for about X dollars

per week. This implies a gross yield of about 5 per cent. After deducting

expenses such as maintenance, letting agents' fees and so on, net yields are

lower, currently around 3 per cent. This is well below interest rates being

paid by banks.

4.63

But a further reason advanced as to why these yields are low is

that the tax advantages given to housing have led to house prices being bid up.

On this argument, without these tax breaks, house prices would be lower, making

rental yields attractive to investors without the tax breaks being required.

4.64

As noted above, negative gearing was restricted in July 1985 and

restored in October 1987. Rents rose around the time it was restricted and its

restoration was followed by an increase in the supply of rental housing.

However, some argue this may have had more to do with the global stockmarket boom

and crash occurring at the same times, initially attracting and then scaring

investors away from shares – the main alternative investment asset to rental

housing.[63]

4.65

Negative gearing is also seen as advantaging investors over owner-occupiers.

One witness claimed it 'amounts in essence to much cheaper finance for

investors versus home buyers'.[64]

4.66

Even if negative gearing encourages investment in rental

property, many witnesses agreed 'the funds that go into negative gearing

housing for rental do not go to modest or low-income rental'.[65]

Two examples of this argument are:

...there is a major need...for some changes in our taxation system

that are going to support investment in long-term, low-cost rental

accommodation. ...We have seen negative gearing have a positive impact on the

willingness of people to invest in rental property as part of their investment

profile and strategy. But that is very selective and it is not long term. If we

are to deal with the rental accommodation side of housing affordability, we are

going to need to see superannuation funds, infrastructure funds and the like

being prepared to take a long-term view of developing and holding that

accommodation, to provide low-cost rental alternatives for our society.[66]

At the moment the only good that comes out of the use of

negative gearing is the creation of rental property but, unfortunately, very

little of it is at an affordable level.[67]

4.67

To the extent that negative gearing changes the tenure

arrangements of some housing, it is not regarded as particularly beneficial by

some:

...with a given block of housing, if an investor simply turns a

house over from owner-occupation to investment, that on the face of it means

there is more housing for renting, but they are obviously displacing one

household net from owner-occupation to renting. On the face of it, investment

in housing simply does not assist the renting situation.[68]

4.68

There are differing views about whether negative gearing leads to

construction of new housing or a bidding up of the prices of existing homes.

The Real Estate Institute of Australia argues:

Negative gearing as it is certainly encourages the building of

new property. Given that a major component in the tax offset—or write-down, if

you like—of negative gearing comes from the depreciation component, that

component is obviously a lot higher and a lot more attractive for new

properties. So a lot of money from investors using negative gearing as it

stands actually goes into new property.[69]

4.69

Professor Sorensen by contrast believes:

...the tax breaks afforded to housing—for example...negative gearing

for rental property...just simply tend to feed in to higher prices for housing...We

would have lower rentals combined with better returns for owners of rental

accommodation, were negative gearing to be abolished.[70]

4.70

This has led to some suggestions to modify it in ways that would

encourage construction of new and affordable housing. Mr Pollard suggests:

negative gearing be applied only in the case where investors buy

new houses and that it not apply to the buying of established houses. The

effects of this would be that investor interest in established houses would

fall significantly and so we could expect that prices in future would rise much

less than prices of housing generally otherwise, because the vast majority of

investor finance is used on established houses.[71]

4.71

National Shelter suggests:

to taper it to ensure that you can only maximise the level of

investment on it if you are building affordable housing.[72]

4.72

Along similar lines, Professor Burke suggests restructuring it:

...in a way which encourages greater investment in new supply and

lesser investment in existing stock, which only puts investors in competition

with first home buyers. ...Instead of having 100 per cent allowable for all

expenses, you have a higher deductibility—we recommend up to 125 per cent—for

investment in new construction and the purchase of the new rental property. It

reduces to only 75 per cent deductibility for investment in an established

property. That 125 per cent deduction only applies for a benchmark

affordability property—in other words one that is probably around $300,000,

which could be indexed annually. But then the 125 per cent reduces as prices go

up. So over some cut-off point like $500,000 or $600,000 you are back to the 75

per cent.[73]

4.73

Only a few submissions wanted to abolish negative gearing totally.[74]

But there were other suggestions to restrict or quarantine it:

The loss would be available in future years as the rent income exceeded

the expenses, but in the early years it can't be used to reduce overall taxable

income. This would have an effect without being a massive change.[75]

4.74

The attractiveness of negative gearing would be greatly

diminished if the tax discount on capital gains on investor rental housing was

removed.

Recommendation 4.2

The committee recommends that Australia's Future Tax System Review

Panel consider the implications for housing affordability, as well as the

overall fairness of the tax system, of the:

- tax discount for capital gains on investor housing;

- exemption from land taxation of owner-occupied housing;

and

- current negative gearing provisions.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page