Coalition Senators' Dissenting

Report

SPENDING SPREE NOT STIMULUS

SUMMARY

Having carefully considered the

Government’s package, and the evidence presented to the Committee, Coalition

Senators believe the package:

- will

not achieve the objectives the Government claims;

- is

too big at this time, leaving little scope for further measures if needed

later;

- is

poorly thought through and a poor quality use of $42 billion of taxpayers’ money;

- lacks

ingredients that should be part of packages of this kind – measures to increase

employment, productivity, efficiency and competitiveness; and

- commits

Australia to record amounts of debt (the Government seeks authority to borrow

$200 billion), endangering the nation’s long-term economic security.

Coalition Senators are not opposed to a

responsible stimulus package.

But nothing Coalition Senators have

heard at the Committee’s hearings gives them confidence that the package has

been subject to the full intellectual rigour and detailed examination that

should be required when committing to spending $42 billion of taxpayers’ money.

Rather, it appears that the development

of the package and its contents have been politically driven not economically

driven.

INTRODUCTION

On Tuesday 3

February 2009, the Government announced a new package of measures totalling

$42 billion and including an Updated Economic and Fiscal Outlook (UEFO).

The new measures bring the total Government stimulus packages announced to date

to $74 billion or 6.4 per cent of GDP (see Table 2).

The legislation

effecting the package was introduced on Wednesday 4 February 2009, with the

Government insisting that both the House of Representatives and the Senate

should pass the legislation unamended by Thursday 5 February 2009. That is,

the Government insisted that Parliament approve the expenditure of $42 billion

of public money in 48 hours.

Because such a

large amount of taxpayers’ money is involved, Coalition and minority Senators

voted that an Inquiry be held into the package of legislation, so it could be

subject to detailed scrutiny.

Despite the need

for careful examination, the Government forced a hurried inquiry, with the

Report due by Tuesday 10 February 2009. The Government has been unable to

articulate a strong reason for the unnecessary haste. It originally claimed

that the Centrelink cash bonuses could not be delivered on time unless the

package was rammed through the Parliament in 48 hours. Yet in evidence to the

Committee, the CEO of Centrelink Mr Finn Pratt said “If the parliament passes

this legislation next week, as currently presented, we will be able to

implement it for 11 March”. (Proof Hansard Friday 6 February 2009, p8).

Further, Coalition Senators expressed their concern that the timetable for

consideration of this huge financial package has been so hasty that Treasury

has been unable to provide answers to many of the Committee’s questions on

notice.

Coalition

Senators note that the unprecedented demand for the passage of a series of

large measures without due scrutiny poses a significant risk to the Public

Account. Not only is there a risk that the size of the package is too great,

but the components of the package might be of poor quality and therefore

achieve less impact than some alternative package. The spending of taxpayers’

money is not costless; there is an opportunity cost in providing public

spending and that includes alternative options foregone such as returning taxes

to the people who paid them.

Coalition

Senators have reached the conclusion that this package does not conform with

best economic theory and evidence, has been insufficiently analysed by the

Departments of Treasury and Finance, is too large, and leaves insufficient

capacity to respond to future needs.

Coalition

Senators are deeply concerned that the Government has failed to consider or

model alternative policies and has committed significant public money to a

range of programmes that will not achieve the Government’s stated objectives.

To

summarise, the package:

- is too large;

- has been introduced too early;

- imposes too much debt on Australian

taxpayers; and

- is poorly targetted to achieve its stated

objective “to support economic growth and jobs in Australia” (UEFO, page 17).

Coalition

Senators therefore recommend that the Senate vote against the package as a

whole. The Government should then present to the Parliament an appropriate

stimulus package that is more modest, better targeted and which contains

components that would genuinely improve productivity, assist in genuine job

creation, and raise the living standards of the Australian people.

ECONOMIC

CIRCUMSTANCES

International

International

economic conditions have weakened, and it is widely accepted that the world is

in recession, with the G7 countries in particular suffering significant

recessions. According to the forecasts in UEFO, Chinese growth has also

dropped significantly, to an estimated 6 ½ per cent in 2009. Forecasts for

growth in the euro area are around minus 2 per cent in 2009. It is

noteworthy that the majority of countries – including the G7 countries and

Brazil, Russian, India and China – have included tax cuts in their stimulus

packages. According to The Economist (31 January 2009, p71),

the average stimulus is estimated at 2.8 per cent. Governments have also taken

on substantial public liabilities, in many cases taking equity in private

banks.

National

Australia’s

economic conditions have weakened, but remain significantly stronger than the

rest of the world. The UEFO forecasts growth in Australia to be 1 per cent in

2008-09 and ¾ of a per cent in 2009-10. It also forecasts that unemployment

will rise to 7 per cent by the June quarter 2010, compared with the present

unemployment rate of 4.5 per cent for the month of December 2008.

There are a

number of reasons for the relative strength of Australia’s economy compared

with overseas. A major reason is a long series of economic reforms, commencing

with the Hawke/Keating Government’s floating of the dollar in 1983 with

bipartisan support from the Coalition which then accelerated under the

Howard/Costello Government. These macroeconomic and microeconomic reforms

included: liberalising trade, opening capital markets, improving the regulation

of the corporate and financial sector, enhancing competition, freeing up the

labour market and a myriad of other measures to make Australia’s economy

stronger, more resilient and more dynamic adding to the living standards of

Australians.

Australia’s

financial sector is the envy of the world – the four major Australian banks now

being in the top 20 of the highest credit ratings of banks in the world. Our

regulation is, as the Deputy Prime Minister said at Davos, “better than world

class”. According to the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority,

Australian banks continue to be in a relatively strong state, a testimony to

the success of the prudential regulation regime established by the former

Coalition Government.

The legacy

inherited by the Rudd Government in November 2007 was one of a very strong

economy, with a dynamic and flexible labour market, sound financial regulation,

and strong economic growth. The unemployment rate was at a 30 year low, with

record high participation rates; public net debt had fallen to minus $41

billion; inflation was in the target range of 2 to 3 per cent; consistent

budget surpluses had been achieved and were forecast over the forward

estimates; a number of significant investment funds were established to address

long-term challenges such as the ageing of Australia’s population (including

the Future Fund and the Higher Education Endowment Fund); and a long series of

sustainable tax cuts have returned the benefits of sound economic management to

the Australian taxpayer.

Professor

McKibbin in evidence to the Committee (Submission) lent his support to the view

that the Australian economy was very strong compared with other countries and

said:

“Up until this point the Australian economy has proven to be a

good model for economic reform combined with careful regulation and an

appropriate role for Government. This reality should be reinforced whenever

possible”.

Government

policy to date

Many of the

Government’s policies to date have been misguided, ad hoc, and hasty. For

example, the Government’s decision to provide an unlimited guarantee for bank

deposits created a substantial distortion which negatively affected – and

continues to affect – the savings of hundreds of thousands of Australians.

Similarly, through much of 2008 the Government overstated the inflation threat

and increased inflation expectations leading to higher interest rates. The

effects of those increases are still feeding through into economic activity.

The Government talked down the economy for political gain, undermining business

and consumer confidence. The Government took decisions to increase taxes and

other revenue in the May Budget after talking of “painful” budget cuts in the

months and weeks beforehand.

Coalition

Senators consider that this pattern of policy mistakes and rushed decision

making in the attempt to appear “decisive” has weakened the Australian economy,

lowered business and consumer confidence, and exposed Australia needlessly to

additional risk from the global financial crisis. Coalition Senators consider

that the present package continues this pattern of rushed decision making and

urge the Government to be more cautious, competent and strategic in its

management of the economy.

The importance of

business and household confidence was emphasised by Professor McKibbin in

evidence to the Committee. He said:

“Therefore, the first requirement of the Nation Building and Jobs

Plan Bills should be to help restore confidence. Ideally this would imply that

all sides of politics would reach a consensus on the way forward and would

quickly pass legislation through the Parliament. It is unfortunate that this

consensus was not reached early through a bipartisan approach” (Submission).

Coalition

Senators agree with this statement and regret that the Coalition’s repeated

offer to work with the Government in a bipartisan manner has been consistently

rejected by the Prime Minister.

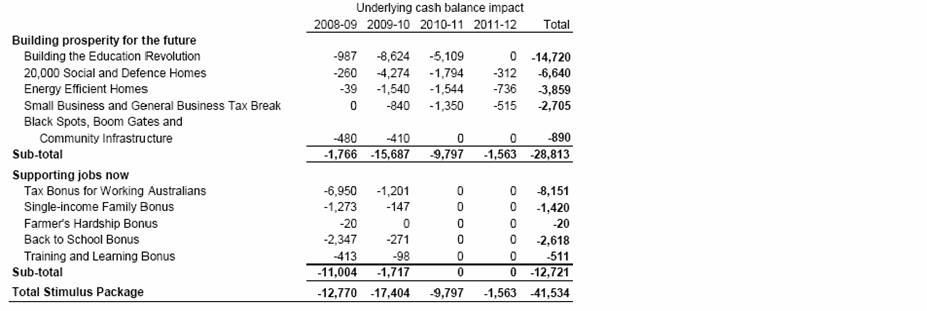

THE PACKAGE

The stimulus

package comprises 10 components structured into two key themes: building

prosperity for the future and supporting jobs now, as shown in the table below.

TABLE 1: Key

components of the $42 billion package

Source: Updated Economic and Fiscal Outlook, page 17

The Government

argues that the components in the Building prosperity for the future are

aimed at improving productivity, but Coalition Senators consider that spending

taxpayers’ money on these projects is unlikely to enhance productivity. Programmes

that simply spend taxpayers’ money on social housing or subsidise activities

that are self financing are highly unlikely to improve productivity.

The various

grants under Supporting jobs now are clearly attractive to recipients.

But by focussing on grants rather than tax cuts, the Government has rejected a

more effective measure. And by making the grants so large, the Government has

reduced the scope for future stimulus measures.

Deficits

and Debt

The UEFO shows

that the accumulated deficits between 2008-09 and 2011-12 are projected to be

$118 billion. Of that, policy decisions taken since the May Budget make up the

majority: $67 billion over the forward estimates, including $29 billion in

2008-09. The Government’s own figures show that in the absence of its policy

decisions, the budget would still be in surplus in 2008-09. The Government has

simply run up Commonwealth debt – its amendments to the Commonwealth Inscribed

Stock Act seek authority for borrowing up to $200 billion – an unprecedented

amount for Australia. This amount –$9500 per man, woman and child – is a

burden on Australian taxpayers that will reduce Australia’s growth. Treasury

was unable in the timeframe to provide an estimate of the interest cost of the

debt. However, David Crowe in the Australian Financial Review (10

February 2009) estimates that the interest cost on the proposed debt will rise

to $7 billion a year.

The net

deterioration in the Commonwealth’s Budget position between 2007-08 and 2008-09

is projected to be 3.6 per cent of GDP. This is similar to the deterioration

under the Whitlam Government, which went from a surplus of 1.9 per cent of GDP

in 1973-74 to a deficit of 1.8 per cent of GDP in 1975-76. However, Coalition

Senators note that although the current deterioration is roughly similar to

that previous episode in terms of percentage of GDP, under the current

Government the deterioration is projected to occur over the course of a single

year – twice as fast as the deterioration under the Whitlam Government.

Coalition

Senators further note that the latest stimulus package follows earlier measures

which together now total almost $75 billion. Again, the Government has been

unable to articulate the need for a further stimulus package of such a size and

composition following these earlier packages which have not been assessed for

their efficacy. At 6.4 per cent of GDP (see Table 2), the stimulus measures in

Australia are larger than those in the United Kingdom and United States among

others – countries that are in considerably worse economic health and therefore

require commensurately larger fiscal stimuli.

In evidence

tabled by Treasury to the Committee on 5 February 2009, a comparison of fiscal

stimulus packages around the world in 2008 and 2009 was provided. This

supports the Coalition Senators’ view about the relative size of the Australian

stimulus. Using only the $10.4 billion and $42 billion packages, Treasury

calculates that Australia’s stimulus is 4.9 per cent of GDP. This is four

times the size of the US stimulus as a proportion of GDP (1.2 per cent) as

shown in the Treasury evidence. It also showed that the UK’s stimulus was 1.4

per cent of GDP, Germany was 2.6 per cent of GDP, Japan was 2.6 per cent of GDP

and France at 1.4 per cent of GDP.

Excessive debt

has been a major cause of the global financial crisis. Coalition Senators

therefore are bemused that the Government is unconcerned about the prospect of

a significant increase in public debt. The lessons of the mid-1990s show that

the burden of public debt significantly impaired the economic performance of

Australia.

Coalition

Senators are concerned by the lack of a clear strategy to return the budget to

surplus. The UEFO provides no detail other than allowing tax receipts to

increase and holding growth in real spending to 2%. Worryingly, despite

numerous queries, officials from the Treasury and the Department of Finance and

Deregulation were unable to provide further detail about how these commitments

would be met over the period.

Furthermore,

Coalition Senators are concerned by the UEFO projections outlining $50 billion

in deficits over 2010-2012 despite a projected economic recovery and 3% growth

in real GDP. Treasury officials were unable to project when the community

might expect the budget to return to surplus.

TABLE 2:

GOVERNMENT STIMULUS PACKAGES ANNOUNCED TO DATE

|

Package

|

$ million

|

|

Economic Security Strategy

(October 2008)

|

10,400

|

|

COAG Package

|

15,200

|

|

Nation Building and Jobs

Plan (February 2008)

|

41,534

|

|

Ruddbank (Government

contribution)

|

2,000

|

|

Local Community

Infrastructure

|

300

|

|

Infrastructure package

|

4,700

|

|

TOTAL

|

74,134

|

[1]

Coalition

Senators are concerned that the Government is unable to provide evidence on the

success or otherwise of the $10.4 billion package announced on 14 October 2008,

yet it is now asking the Senate to approve a further package of four times the

size. In evidence to the Committee, Dr Henry said “so we are only going to get

by the first week of March a very partial reading of the impact on both

household consumption and household saving of the October package” (Proof

Hansard 5 February 2009, page 9). Further, in evidence given on Monday 9

February, Richard Evans of the Australian Retailers Association stated “it is

too early to determine whether or not the cash has entered the market in any

significant way. Indeed it may take six months before we actually the results

...”. (page 2-3).

When questioned

about the small increase in retail sales in December, Mr Evans noted “retailers

have been discounting since November to stimulate customers. It was very soft

in December” (page 2).

Even more

concerning, when asked about how Australians could judge the success of the

proposed $42 billion package, Dr Henry conceded that we may never know. He

said “... it is going to be difficult for us to be able to provide the Parliament

with precise estimates of the actual fiscal impact of the package”. (Proof

Hansard, Monday 9 February 2009, page 56).

ECONOMIC

PRINCIPLES, THEORY AND EVIDENCE

Many leading

academic economists have spoken publicly of their concerns that fiscal stimulus

of the sort proposed by the Government is ineffective or, worse,

counterproductive. This view reflects a large body of theoretical and empirical

work over the last thirty years (the Appendix contains more detailed

discussion).

In the United

States, three Nobel laureates in economics (James Buchanan, Edward Prescott and

Vernon Smith) and a number of other economists including Deepak Lal, John Cochrane

and Michael Bordo have signed an open letter to the American President stating

that:

“... it is a triumph of hope over experience to believe that more

government spending will help the U.S. today. To improve the economy,

policymakers should focus on reforms that remove impediments to work, saving,

investment and production. Lower tax rates and a reduction in the burden of

government are the best ways of using fiscal policy to boost growth” (Open

letter from 200 economists New York Times/ Washington Post/Wall

Street Journal, January 2009).

Harvard

University economics professors, Robert Barro and Greg Mankiw have provided

clear statements of their concerns.

Barro has

cautioned against “programs that throw money at people” and “massive

public-works programs that do not pass muster” and emphasised the value of

income and corporate tax reductions (Wall Street Journal, 22 January

2009).

Mankiw has

pointed out three home truths as his government rushes to introduce a huge

increase in government spending (New York Times, 11 January 2009).

First, the effect of government spending on the economy is not very large.

Second, public spending on poorly chosen projects will not improve economic

well-being. Third, evidence suggests that the effects of tax cuts are greater

than spending increases, perhaps twice as large.

A number of

leading Australian economists have raised similar concerns about fiscal policy

in general and the Australian government’s approach in particular. Professor

Tony Makin of Griffith University has written:

“The textbook consensus is that for open economies, fiscal

policy is ineffective in stabilising aggregate demand in the short run under

floating exchange rates – especially if it means lifting unproductive

government spending and running up public debt to fund it” (Australian

Financial Review, 15 December 2008).

Australia is an

open economy with floating exchange rates and a high degree of international

capital mobility. Further, “if the extra government spending fails to generate

an economic return sufficient to cover the servicing costs of the foreign

borrowing required to fund it, the seeds are sown for a future currency crisis”

(Australian Financial Review, 4 February 2009). The proposed expenditure

on education and social housing, as well as the transfer payments will not

generate a return to cover debt servicing costs.

In evidence to

this committee, Professor Sinclair Davidson, of RMIT, has argued that spending

multipliers are often overstated. He has advised that the government should

consider tax cuts such as a GST or pay roll tax holiday and bringing forward

the “aspirational” income tax cuts suggested by the Labor Party prior to the

election.

Reserve bank

board member and professor at the Australian National University, Warwick

McKibbin, has stated that the December 2008 stimulus payments did not have much

impact and has called for a halving of the GST for a year (reported in The

Age, 30 January 2009).

The chairman of

Concept Economics, Professor Henry Ergas (Australian, 9 February 2009)

has a number of concerns about the effectiveness of fiscal policy, noting also

that the latest stimulus appears to be “too much, too soon”, a view shared by

the Coalition and discussed further below.

There is no

evidence that the government has requested or considered a detailed examination

of the theoretical and empirical work on this subject before reaching its

policy conclusions. In public it has relied on selective use of opinions

expressed by certain individuals at international bodies such as the IMF while

eschewing the views of the organisation.

Whilst much of

the evidence suggests that tax cuts have a relatively large fiscal multiplier,

Coalition Senators note that the Government effectively raised taxes when the

planned “aspirational” tax cuts were abandoned in the Mid-Year Fiscal and

Economic Outlook. Page 52 of that document states that:

“In the 2008-09 Budget, the Government made a provision for its

aspirational tax goals in 2011-12. The Government said that achieving its

aspirational tax goals ‘will depend on economic conditions and the need to

maintain fiscal responsibility’. Given the dramatic deterioration in the global

economic outlook and associated increased uncertainty, the provision will no

longer be maintained. The Government will reconsider the policy parameters

following an improvement in overall economic conditions.”

Coalition

Senators are puzzled as to why the Government believed back in November 2008

that it was not fiscally responsible to carry out its election commitment of

planned tax cuts and quietly abandoned them, but that less than three months

later it has now decided that it is fiscally responsible to spend $42 billion

and seek authority for borrowing up to $200 billion. No explanation of this

has been provided.

THE

GOVERNMENT’S ANALYSIS

Treasury’s

modelling of the stimulus package is a black box. We have no idea of the

structure of the model, the data used or the results for GDP or employment for

each of the ten policies in the plan. The figures that have been floated are

unsupported by detailed analysis, appear fanciful and are inconsistent. The

Government claimed that the $10.4 billion package will create about 75,000

jobs at an average cost of $139,000 per job; infrastructure package of $4.7

billion will create 32,000 jobs at a cost of $147,000 per job; COAG package of

$15.1 billion will create 133,000 jobs at a cost of $114,000 per job. Yet, the

$41.5 billion package will “support” up to 90,000 jobs over the next two

years at an average cost of $461,000 per job or $230,500 per job per year.

Coalition Senators note the change in language and Treasury’s inability to

account for this.

The $41.5 billion

package has much lower job “support” than the $10.4 billion package. The result

is curious as the second package has large infrastructure spending which

Treasury tells us (Dr Gruen’s evidence, 5 February 2009, p. 11) has a higher

GDP multiplier (closer to 1) than transfer payments (closer to 0.5). No details

have been supplied about exactly what are the estimated GDP and employment

multipliers for each sector of the economy in the model of the ten components

of the package.

It appears that the Nation

Building and Jobs Plan was provided by the government to Treasury for

modelling, rather than prepared by Treasury. And it appears that Treasury was

not asked to model any alternative policies.

The Government has

consistently stated that it wanted open, transparent and accountable government

with evidence based policy. Yet in the case of the present package, the

Government has failed to provide any accountability measures and has not

provided any regulation impact statements to establish that the Bills will

provide a net benefit to Australians and that the proposed measures are

superior to any alternatives. The Government has also failed to provide any

key performance indicators to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the

package.

SIZE OF

STIMULUS

The Government

has not made available analysis of the size of the stimulus. This appears not

to be readily available despite the Prime Minister’s statement on the

importance of co-ordination across countries.

According to page

71 of the Economist (31 January 2009), the weighted average stimulus of

the G7 countries plus Brazil, Russian, India and China, was 3.6 per cent of GDP

spread over several years. See table for the individual country details.

Australia has a

bigger stimulus than these other countries which are in a significantly worse

financial and economic state than Australia. (Australia’s stimulus is about 6.4

per cent of GDP (and around 4 per cent for the $42 billion package) taking

into account the $10.4 billion package, the $15 billion COAG package, the $4.7

billion infrastructure package and this $42 billion second stimulus package). [2]

A smaller

stimulus today would leave greater room for the future should a further

stimulus be required.

Saul Eslake said

that a large fiscal stimulus leading to high debt would mean higher taxes in

the future. “It may well be that servicing or repaying the debt incurred now

will ultimately require higher taxes” (Proof Hansard Monday 9 February 2009,

page 37).

Dr Henry said in

evidence to the Committee when asked about repaying the debt “it could also be

achieved by asset sales” (Proof Hansard Monday 9 February 2009, page 40).

Professor

McKibbin in evidence to the Committee argued that Australia’s relative economic

strength and the likelihood that the global economic slowdown may be sustained

suggested that:

“The current package is too large at this stage of the global

economic slowdown. Given the circumstances in Australia, the package should be

less than the 2 per cent of GDP average stimulus recommended by the IMF”.

(Submission)

TIMING OF

STIMULUS

In his address to

Treasury staff on 14 March 2007, Dr Henry stated that “for macroeconomic

purposes, it is probably reasonably safe to assume that we are already at full

employment – or, at least, very close to the NAIRU, the non-accelerating

inflation rate of unemployment”. When Dr Henry made this statement, the

unemployment rate was 4.6 per cent (February 2007, seasonally adjusted).

In evidence to

this Committee, Dr Henry has said “we are not in a position of full employment...

this is not a situation in which we are having a fiscal expansion with an

economy already at full employment” (5 February 2009, p. 30). While Coalition

Senators note that unemployment is a lagging indicator, no explanation was

provided for the contradiction in his views nor was evidence provided that the

unemployment rate is significantly higher than the Australian Bureau of

Statistics’ figure of 4.5 per cent.

In evidence to

this committee, Dr Gruen said that in the Treasury’s modelling, “the

unemployment rate will return to the model’s rate at which inflation is neither

rising nor falling sometimes called the NAIRU” (5 February 2009, p. 42).

This is not an

abstract point. If NAIRU is between 4.5 and 5 per cent, then there is a

practical question of why we are undertaking such a massive fiscal policy

intervention now. While the government wishes to pre-empt an increase in

unemployment, on Treasury’s analysis, it would seem prudent to wait. There are

costs of acting precipitately. It will be a large diversion of productive

resources into less productive uses for limited immediate benefit should

conditions not deteriorate as much as some fear. Alternatively, it will leave

the government less able to respond in the future should conditions

dramatically worsen.

Professor

McKibbon, in evidence to this committee noted that an economic downturn may

persist for some time and that the economic and regulatory strengths of the

Australian economy allow Australia to have a smaller response than other

countries. The Coalition considers that there is, therefore, a very real

concern that this stimulus package may be, as Henry Ergas puts it “too much,

too early”.

COMPOSITION OF

STIMULUS

As discussed

above little consideration has been given to alternative policies and no

justification has been provided for why the elements of the package have been

chosen above alternatives.

Tax cuts

Many leading

economists conclude that tax cuts are preferable to spending increases.

The Economist (31 January 2009, page 71) table referred

to above shows that all of the G7 and BRIC countries have tax cuts in their

stimulus packages. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook (October 2008, page

178) concludes that “revenue-based stimulus measures seem to be more effective

in boosting real GDP than expenditure-based measures”, especially in advanced

economies like Australia’s. The six-monthly Outlook is the most important

regular statement of IMF policy and this conclusion is contained in a chapter

examining in detail the evidence on fiscal policy as a countercyclical tool.

The Government has rejected

the possibility of tax cuts which so many other countries consider superior to

a handout only package. It has also rejected the considered advice of the IMF

in favour of tax cuts over transfer payments (IMF, World Economic Outlook,

October 2008).

Tax options raised by

leading Australian economists include permanent measures such as bringing

forward the already announced tax cuts scheduled for 2010 or introducing the

aspirational income tax cuts. Temporary measures include a GST rate cut or

payment holiday and a payroll tax holiday.

Payroll tax and

GST can be changed quickly and implemented as quickly as spending increases, as

can the Coalition’s suggestion of some federal assistance to partially pay for

the superannuation guarantee of small businesses.

Another reason to

favour tax cuts as a significant part of the package is because tax cuts can be

relied upon to increase the productive capacity in the longer-term and

therefore they increase GDP growth. As the Treasurer himself noted in his

Second Reading speech on the Tax Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Reduction)

Bill to the House on 14 February 2008:

“Economic modelling undertaken by the Treasury indicates the

personal income tax reforms alone will lift aggregate labour supply by around

65,000 persons in the medium term. This increase in workers, together with the

increase in the effort of existing workers, will make available around 2.5

million additional hours of work to the economy each week. These tax reforms

will also enhance the incentives for taxpayers to upgrade their skills and gain

higher qualifications by allowing workers to keep more of the wage gains that

come with being more highly skilled and productive.”

Professor

McKibbon also noted in his testimony:

“The main problem I see is in the cash payments. I would replace

the intent of these payments by bringing forward the tax cuts that are already

legislated for future years.”

Poorly selected

spending programmes, by contrast, will work in the opposite direction.

Experience suggests that the private allocation of resources generates higher

returns on average over the long-run.

Quality of projects

Many economists

have raised the concern that public spending on poorly chosen projects will not

improve economic well-being.

The announcement

of $21.4 billion in public expenditure on schools and public housing provides

no serious explanation as to why these projects were chosen instead of the many

other alternative public and private projects that could be undertaken.

Of course the

Coalition believes in our schools and in housing, but are these the best

investments to undertake with over $21 billion of public money and debt?

In evidence (5

February 2009, p. 18) Dr Henry states “a project which would make a substantial

enhancement to the future supply capacity of the economy is a project that

should be done anyway. And it should be done on top of these measures.”

However, Coalition Senators

endorse the view taken by many of the world’s leading economists that such an

approach is unnecessary and undesirable. All projects chosen as part of a

stimulus package can and should be worth doing in their own right.

The Coalition finds it

remarkable that the Government has been unable to identify worthwhile projects

given that it says it has been thinking about Australia’s infrastructure needs

since it won office over a year ago.

Coalition Senators are also

surprised that the Government does not appear to have estimates of the

multipliers for individual components. Senator Joyce asked if this meant that

spending $42 billion digging holes and filling them in again would result in

the same stimulus as the 10 components actually chosen. Dr Gruen replied:

“I guess the answer to that is that Keynes

at some point made the point that the effect on aggregate demand would be the

same if you dug holes and filled them in. It is actually a famous example. But

to the extent that you can do something which has the same effect on jobs and

you end up with something that is actually what society wants, that is clearly

preferable to digging holes and filling them in.” (Proof Hansard Monday 9

February 2009, page 57).

Coalition Senators are

concerned about the shortcomings of the Government’s analysis which is unable

to distinguish the effectiveness of different programmes either in their

short-term stimulus effects or their long-term effects on economic growth.

In regard to long-term

effects on economic growth and employment, Treasury has confirmed that “in the

long run we are not talking about saving jobs” (Proof Hansard, Thursday 5

February 2009, page 41). This is in contrast to statements from the Government

which appear to suggest that the job creation effects of the package are both

short and long-term. For example in UEFO (page 17), it states that the Building

prosperity for the future component of the package will not only boost

demand and increase employment over the next couple of years, but will also add

“to the productive capacity of the economy in the longer-term”.

Coalition

Senators also noted that the component to encourage insulation in homes is

inconsistent with the Government’s own Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme. The Treasurer’s “Energy Efficient Homes Program” released

on 3 February 2009 says:

“Overall, it is estimated that these

new measures could result in the abatement of 4.7 million tonnes of carbon

dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2-e) per year from the end of the program, and total

abatement of 49.4 Mt CO2-e by 2020.”

However, the CPRS White Paper involves a reduction target of 5 per

cent of emissions by 2020. The installation of insulation would reduce the

price of permits to other emitters and not result in any additional carbon

emissions reductions beyond the 5 per cent target. By reducing the permit

price, the insulation scheme is an effective subsidy to high emitters.

CONCLUSION

Australia has

enjoyed a long period of strong economic growth, falling unemployment due in

large measure to a long series of micro and macro-economic reforms. As a

result, Australia is better prepared than other countries to withstand the

economic downturn.

The Government

has panicked and wants to rush through an extremely large fiscal package with

inadequate analysis and scrutiny and without considering alternatives. In

addition the Government has failed to demonstrate the effectiveness of its

previous stimulus measures, especially with regard to its claims that the

October 2008 package would create 75,000 jobs – a claim that has now been

widely discredited.

RECOMMENDATION

Accordingly

Coalition Senators recommend that the Senate reject this package and vote

against the six Bills.

Senator Mitch Fifield

Deputy Chair |

Senator Scott Ryan |

Senator Barnaby Joyce |

| |

|

|

| Senator Eric Abetz |

Senator Helen Coonan |

|

APPENDIX

Coalition

Senators firmly believe that some basic economic principles should be kept in

mind when examining the efficacy of fiscal stimulus packages. A dollar of

additional Government spending creates both benefits and costs. Weighing up

those costs and benefits should always be done with a great amount of care, in

order to obtain maximum “bang” for taxpayers’ “buck”. This is even more

important when such large amounts of money are at stake and the size of the

debt to be incurred by the public in this instance is so significant.

The basic

economic principle of opportunity cost means that an additional dollar of

Government spending must always draw resources away from alternative economic

uses in the private sector. As Treasury Secretary Dr Ken Henry noted in his

speech of 14 March 2007:

“Expansionary fiscal policy tends to ‘crowd out’ private activity:

it puts upward pressure on prices which, all things being equal, puts upward

pressure on interest rates. Depending upon the size of the interest rate

response, the nominal exchange rate might also appreciate, squeezing further

resources out of the traded goods and services sectors of the economy. As a

rather crude, but nevertheless instructive generalisation, there is no policy

intervention available to Government, in these circumstances, that can generate

higher national income without first expanding the nation’s supply capacity.

Policy actions that expand the nation’s supply capacity target at least one of

the 3Ps — population, participation or productivity – that we have been talking

so much about in recent years.

Now you might be thinking that that’s all pretty obvious. It is,

after all, a tautology. But one of my messages to you today is that if you

understand what I have just been talking about, then you are a member of a

rather small minority group. The political economy hasn’t kept pace with the

real economy.”

The Department of

Finance's Handbook of Cost Benefit Analysis makes a similar point at

page 43:

“(a) Employment multipliers

The existence of unemployment sometimes leads analysts to augment

the benefits from Government projects due to indirect effects of the project on

employment and output. The reason given is that if labour which would otherwise

be unemployed is used on a public project, the expenditures of the newly

employed workers may raise employment and incomes in other sectors of the

economy where labour and other factors of production would otherwise be

involuntarily idle, and so on in a chain reaction.

The problem with this approach is that any such multiplier effect

could also be achieved by alternative uses of the project resources. Instead of

undertaking the project, the Government could reduce taxation or increase

expenditure, either of which could be expected to have an expansionary (though

not necessarily similar) effect on income and employment. It should be

remembered that cost-benefit analysis is always concerned with incremental

costs and benefits, that is, with effects which would not have occurred in the

absence of the project."

And on page 40

the handbook states that:

"To say that a project will create 100 jobs is not to say

that a project will reduce unemployment by 100 people. As a general rule, it is

recommended that analysts assume that labour, as with other resources, is fully

employed. Moreover, unless the project is specifically targetted towards the

goal of reducing unemployment, it can be expected that many of the jobs will be

filled by individuals who are currently employed but who are attracted either

by the pay or by other attributes of the new positions. The research necessary

to justify the use of shadow pricing of labour should include, therefore, the

mix of unemployed and continuously employed persons in the additional

employees."

Professor Kevin

Murphy of the University of Chicago has recently developed these ideas further,

proposing a simple analytical framework for assessing the proposed fiscal

stimulus package in the United States.[3] He notes that a proper assessment of the

benefit of an additional dollar of spending should take account of the extent

to which worthwhile projects will be correctly identified and ranked by the

Government, the extent to which the dollars that are spent will actually employ

idle resources, the opportunity cost of those idle resources, and the

efficiency cost of raising the tax revenue to fund the additional spending.

Professor

Sinclair Davidson in his evidence to the Committee highlighted these concerns

and the evidence from leading international economists. In particular he

concludes “discretionary fiscal policy has a poor track record of success”. In

particular “Keynesian strategies are less likely to work in small open

economies”. Professor Davidson also reminded the Committee of the important role

of independent monetary policy and the automatic stabilisers in fiscal policy.

Coalition

Senators are not convinced that the Government has based its decisions on

credible theoretical arguments or empirical evidence regarding any of these

individual aspects of the fiscal stimulus package.

Coalition

Senators were disappointed at the inability of the Government to precisely

define what is meant by the concept of the “fiscal multiplier” and the complete

lack of convincing empirical evidence regarding the sign and size of fiscal

multipliers for Australia in general and for this set of measures in

particular, both for the package as a whole and for individual policy

proposals. In particular, there appeared to be some confusion as to whether

the multiplier measured the change in aggregate demand brought about by a

change in fiscal policy, or the change in GDP that is brought about (the latter

is the accepted definition).

Coalition

Senators were also disappointed that the Government did not consider the effect

that talking down the economy would have on businesses and consumers, the

reaction of the private sector to deficits and debt, and the role of business

and consumer confidence would play in the economic recovery.

Coalition

Senators were not convinced by the vague theoretical arguments putting forth

the proposition that fiscal multipliers for spending were higher than for tax

cuts, and were not presented with any compelling empirical evidence supporting

this claim.

For their part

Coalition Senators note that the fiscal policy decisions of the Coalition

Government in the 1996-97 Budget – which involved policy decisions to

significantly cut outlays in order to reduce the irresponsible budget deficits

it had inherited, and to repay the previous Government’s $96 billion debt –

appear to have had exactly the opposite effect compared to these vague

theoretical claims.

Table 3 below

shows that in its 1996-97 Budget, the Coalition took policy decisions to reduce

outlays by $12.9bn over three years, when the Australian economy was much

smaller.

What was the

fiscal multiplier associated with this tightening? The Australian economy grew

by 3.9 per cent in the year to June 1997, by 4.5 per cent in the year to June

1998, and by 5.2 per cent in the year to June 1999. Unemployment fell from 8.2

per cent in June 1997 to 6.7 per cent in June 1999.[4] The evidence from this episode seems to

suggest that the fiscal multiplier for spending is negative in Australia and

does not seem to be consistent with the vague theoretical claims that were

presented to the committee.

This kind of

empirical evidence is neither unique nor new. Thirty years ago Professors

Robert Lucas (Nobel Laureate) and Thomas Sargent wrote that:

“In the present decade, the United States has undergone its first

major depression since the 1930s, to the accompaniment of inflation rates in

excess of 10 per cent per annum. These events have been transmitted (by the

consent of the governments involved) to other advanced countries and in many

cases have been amplified. These events did not arise out of some reactionary

reversion to outmoded “classical” principles of tight money and balanced

budgets. On the contrary, they were accompanied by massive government budget

deficits and high rates of monetary expansion, policies which, although bearing

an admitted risk of inflation, promised according to modern Keynesian doctrine

rapid real growth and low rates of unemployment.

That these predictions were wildly incorrect and that the doctrine

on which they were based is fundamentally flawed are now simple matters of

fact, involving no novelties in economic theory. The task now facing

contemporary students of the business cycle is to sort through the wreckage,

determining which features of that remarkable event called the Keynesian

Revolution can be salvaged and put to good use and which others must be

discarded”. [5]

More recent

empirical evidence can also be found. A 2005 empirical study by Professors

Andrew Mountford and Harald Uhlig entitled "What are the Effects of

Fiscal Policy Shocks?" found that:

- “a surprise deficit-financed tax cut is

the best fiscal policy to stimulate the economy

- a deficit-financed government spending

shock weakly stimulates the economy

- Government spending shocks crowd out both

residential and non-residential investment without causing interest rates to

rise.” [6]

Professors

Christina Romer and David Romer of the University of California at Berkeley

find that the fiscal multiplier for a tax cut is 3, a much larger value than

most estimates of spending multipliers.[7]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page