Chapter 1 - Introduction

1.1

On 5 February 2009, the Senate referred the provisions of the following

bills to the Finance and Public Administration Committee for inquiry and report

by 10 February 2009:

- Appropriation (Nation Building and Jobs) Bill (No.1) 2008–2009

- Appropriation (Nation Building and Jobs) Bill (No.2) 2008–2009

- Household Stimulus Package Bill 2009

- Commonwealth Inscribed Stock Amendment Bill 2009

- Tax Bonus for Working Australians Bill 2009

- Tax Bonus for Working Australians (Consequential Amendments) Bill

2009.

1.2

On the same day, the Senate also referred the provisions of the Appropriation

(Nation Building and Jobs) Bill (No.2) 2008–2009 relating to the social housing

program to the Community Affairs Committee.

Conduct of the Inquiry

1.3

Details of the inquiry, the bills, and associated documents were placed

on the Committee's website. As of Monday, 9 February 2009, the Committee had

received 29 submissions which are listed in Appendix 1. Appendix 1 also

lists additional information received by the Committee. Submissions were placed

on the Committee's website for ease of access by the public.

1.4

In referring the provisions of the bills to the Committee, the Senate

directed the Committee to hold hearings on 5 February, 6 February and 9 February 2009 respectively. A list of witnesses who appeared at the hearings is at

Appendix 2.

1.5

The Committee thanks those departments, organisations and individuals

who gave evidence at the hearings at very short notice for their cooperation

and willingness to do so. The Committee is also grateful to those organisations

and individuals who made submissions within the tight timeframe.

1.6

The Committee would also like to thank the Department of Parliamentary

Services for producing the proof Hansard Transcripts in a very short time.

Context of the Inquiry

1.7

Australia faces an unprecedented global financial crisis as the majority

of countries go into recession. The massive collapse of the United States subprime

mortgage market has plunged the global economy into crisis. There is a major downturn

in world trade which has led to a slump in consumer and business confidence. Australia

is not immune to the crisis. The Government must act decisively to protect the

national interest by strengthening the economy in order to protect the financial

security of Australian families and businesses.

1.8

The International Monetary Fund's (IMF) October 2008 World Economic

Outlook described the world economy thus:

The world economy is entering a major downturn in the face of

the most dangerous financial shock in mature financial markets since the

1930s...The situation is exceptionally uncertain and subject to considerable

downside risks. The immediate policy challenge is to stabilize financial

conditions, while nursing economies through a period of slow activity and

keeping inflation under control.[1]

1.9

Dr Ken Henry, Secretary of the Treasury gave his assessment:

My assessment is that the weakness in

aggregate demand that we are confronting in Australian economy calls for both

very substantial reductions in interest rates and very substantial fiscal

stimulus. I think it is the case that—well, it is certainly the case—that these

two arms of policy are working in the same direction and complementing one

another. If your question was whether these measures were complements or

substitutes, my answer is that they are complements.[2]

1.10

Mr Klaus Schmitt-Hebbel, Chief Economist of the Organisation for

Economic Coordination and Development, stated that 'in normal times, monetary

rather than fiscal policy would be the instrument of choice for macroeconomic

stabilisation. But these are not normal times' and that central banks should also

cut rates further.[3]

1.11

Mr Greg Evans, Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), also

commented:

ACCI strongly supports the government's stimulus package and its

attempt to lift aggregate demand across the economy. Such is the scope of our

current economic difficulties that this package, combined with monetary easing,

is absolutely essential. The size of the package at two per cent of GDP in 2009

is appropriate and in line with our own estimate of what is required.[4]

1.12

Anglicare Australia, Catholic Social Services Australia, The Salvation

Army and UnitingCare Australia, in an issues paper on the impact of the global

financial crisis on social services in Australia, noted that:

Some sectors in the financial markets have shut down altogether

and others are simply dysfunctional. The capital markets, where financial

intermediaries and companies borrow money to fund their investments and,

increasingly, their day-to-day running costs, are most notably affected. Risk

premiums demanded by lenders have jumped and even creditworthy borrowers are

having trouble obtaining sufficient funds. All companies and households are

affected.[5]

1.13

The Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2008-09 (MYEFO) released by the

Treasurer and the Minister for Finance and Deregulation on 5 November 2008 commented that the global financial crisis had 'entered a new and dangerous

phase'. While Australia was better placed than most other countries to

withstand the fallout, it 'was not immune from the effects of the global

financial crisis and the global downturn'.[6]

1.14

In response, the Australian Government took action to strengthen the

economy and support Australians including the $10.4 billion Economic Security

Strategy (ESS), a $300 million program to build local community infrastructure,

a $15.2 billion Council of Australian Governments (COAG) funding package and

the Nation Building Package announced in December 2008.[7]

1.15

On 3 February 2009, the Updated Economic and Fiscal Outlook (UEFO) was

released. The UEFO noted that the outlook for the global economy had

deteriorated sharply since the MYEFO, with the IMF cutting its forecast for

global growth and now forecasting a deep global recession.[8]

1.16

In relation to the Australian economy, it was stated that 'the weight of

the global recession is now bearing down on the Australian economy. Growth is

expected to be significantly weaker than previously anticipated and

unemployment will be higher.'[9]

In addition, the sharp fall in global commodity prices is compounding the

impact on Australia.[10]

1.17

On 3 February 2009, the Australian Government announced a $42 billion Nation

Building and Jobs Plan (the plan) over 4 years to provide immediate support

for jobs and growth. In the UEFO it was stated that:

Without this significant and timely policy stimulus, Australia

would face a more severe slowdown than forecast. With the Nation Building and

Jobs Plan, economic growth is only expected to slow to 1 per cent in 2008-09

and ¾ of a per cent in 2009-10. With slower growth, the unemployment rate is

forecast to rise to 7 per cent by June 2010.

The Nation Building and Jobs Plan has been crafted to strike the

right balance between supporting growth and jobs now, and delivering the lasting

investments needed to strengthen the economy for the future.[11]

And:

Doing nothing is not an option. It is becoming increasingly

apparent that, while still important, monetary policy action alone will not be

sufficient to restore growth in demand within a reasonable time period. The

Government's swift action ensures that fiscal policy, along with monetary

policy, is clearly targeted at supporting economic growth and jobs.[12]

1.18

Key measures of the plan highlighted by the Government include:

- free ceiling insulation for around 2.7 million Australian homes;

-

build or upgrade a building in every one of Australia's 9,540

schools;

-

build more than 20,000 new social and defence homes;

- $950 one-off cash payments to eligible families, single workers,

students, drought affected farmers and others;

- a temporary business investment tax break for small and general

businesses buying eligible assets; and

- significant increase in funding for local community

infrastructure and local road projects.[13]

1.19

The following day, the six bills were introduced in the House of

Representatives to implement the plan, the objective of which is to 'support

jobs and invest in future long term economic growth':

By investing in jobs and long term economic growth the Plan

strikes the right balance between immediate support for jobs now, and

delivering the long term investments needed to strengthen future economic

growth.[14]

Key Issues

1.20

A number of concerns and questions were raised during the course of the

inquiry in relation to the Nation Building and Jobs Plan bills including:

- Australia's position in the current financial crisis;

- the size of the plan and the choice of measures;

- the multiplier effect of the plan's measures;

- the implementation lag;

- the employment effects;

- the proposed increase in the borrowing limit governing the issue

of Commonwealth Government Securities; and

- the effectiveness of cash payments as opposed to tax cuts.

1.21

The proposed increase in the borrowing limit governing the issue of

Commonwealth Government Securities and the effectiveness of cash payments as

opposed to tax cuts are discussed in Chapters 4 and 5 respectively.

Australia's position in the current

financial crisis

1.22

Dr Ken Henry provided the Committee with an overview of the prospects

for the global economy:

At the time that the 2008-09 budget was released the

International Monetary Fund was forecasting world growth for 2009 of four per

cent. Less than nine months later the IMF is now forecasting world growth of

about one half of one percentage point. That is a very substantial deterioration

in forecast growth. It is the largest downward revision to forecast growth by

the IMF that I can recall. Certainly it would be the largest since the Second

World War...so in that sense the global circumstances confronting Australia are

simply unprecedented.

There are other respects in which circumstances confronting Australia

are unprecedented. The forecast growth for our major trading partners is as

weak as we have seen quite possibly since the 1930s. Virtually all of the

countries that we regard as our major trading partners, when we talk about our

major trading partners in an economic sense, are growing at well below trend

rates of growth. Most of them are projected by the IMF to be in recession in

2009. Many of them, indeed, are already in recession and have been for some

period of time.[15]

1.23

Dr Henry also commented on the Australian economy:

It remains the case that, on our assessment and on the

assessments of the International Monetary Fund and the OECD, Australia's

macroeconomic performance is relatively strong both in respect of actual

performance and forecast performance.[16]

1.24

Dr Henry went on to comment that Australia's performance is due to very

careful management of the Australian economy over a long period of time with

respect to both macroeconomic policy and microeconomic reform; effective

regulation of the financial system; and the benefits which have flowed from the

run-up in commodity prices that accelerated at the end of 2003. Dr Henry

concluded:

So there are a whole range of reasons why Australia's relative

economic performance is still quite good, but in an absolute sense the economic

prospects confronting the Australian economy have obviously deteriorated very

substantially.[17]

1.25

UEFO provided a forecast of gross domestic product (GDP) of one

percentage point in 2008-9 as compared to real GDP growth in 2007-08 of 3¾

percentage points. The forecast for 2008-09 takes into account 'the very

considerable loosening in monetary policy that has occurred, the significant

depreciation in the Australian dollar that has occurred, the October

macroeconomic stimulus package and, of course, this macroeconomic stimulus

package' and 'is well below trend growth for the Australian economy and which

explains fully why, in our forecasts, we have the unemployment rate increasing'.

Dr Henry noted that in 2009-10, the forecast is for 'even weaker gross

domestic product growth of only three-quarters of one percentage point'.[18]

1.26

Dr Henry continued:

If one compares the outlook for Australia with the outlook for

the rest of the industrialised world, ours is in some respects a pleasing

outlook. The rest of the industrialised world taken together is forecast by the

International Monetary Fund to go backwards in 2009. But in other respects, and

certainly relative to Australia's trend rate of growth, the figures in the UEFO

have to be regarded as very weak.[19]

1.27

Dr Henry concluded that 'these are highly unusual circumstances and we

have advised government...that there is a need for fiscal policy action and that

it is quite urgent'.[20]

Size of the Nation Building and Jobs Plan

1.28

Given the size of the package, concerns were raised during the inquiry

that the plan was too substantial or should have been staggered over a longer

period of time.[21]

1.29

The UEFO stated that:

The Nation Building and Jobs Plan is intentionally large — it

reflects the seriousness of the challenges being faced and the need to build a

strong economy for the future. By avoiding measures that lock in long-term

spending, the Government is well-positioned to take action to begin to return

the budget to surplus as soon as the economy starts to recover.[22]

1.30

The Australia Institute put the plan's size into the international

context:

While in absolute terms the $42 billion package (over 2.3 years)

is very large, it is less than two per cent of GDP in 2009 and 2010. It is

important to view projected government deficits in relation to both the size of

the Australian economy (the total deficit is 2.8 per cent of Australia's $1.2

trillion GDP in 2009–10) and the size of the fiscal deficits in the US (eight

per cent) and the UK (8.5 per cent). Most EU member countries will also have

deficits well in excess of three per cent of GDP due to the adoption of

stimulus packages and the average for advanced economies in 2009 is seven per

cent.[23]

1.31

Similarly, Mr Greg Evans of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and

Industry noted:

In looking at this issue, we reviewed what was happening

internationally and the size of various fiscal packages. We looked at the UK

and the USA, which are partly analogous, although the depth of their economic

decline has certainly been a lot greater than ours. Indeed, their fiscal

stimuli has been greater than ours. So we thought, on balance, around two per

cent of GDP was appropriate and, in 2009, that is basically what this package

delivers.[24]

1.32

The Committee heard evidence from a number of economists who provided a

range of views to the Committee.

1.33

In response to questions as to why the package was substantial when Australia

is in a much better financial position in comparison to other countries Mr David

Tune, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, stated that:

I guess it is a matter of trying to think forward. The objective

of the package is to get in ahead of the game, in a sense. Looking at the

projections that the Treasury had produced on where they thought the Australian

economy was going, the view was taken that it would be sensible to get in ahead

rather than wait and see what actually happens. Those forecasts may or may not

turn out to be correct; we will see. But, based on the best information that

was available to us in the department, that was the basis of the advice that we

were giving to the government around that time in conjunction with the other

central agencies. Really, it is a question of whether you wait and see or

whether you get in ahead of the game. On this occasion, the government

obviously decided to get in ahead of the game.

The size of the fiscal stimulus and the period of time over

which it occurs are also very important here. If you take into account what the

government did in December last year in the ESS, the economic stimulus package,

and what is being done in the current package, you are probably looking at up

around three per cent of GDP. It is in line with the sorts of averages there in

other countries that you have been talking about. I think it is really a matter

of trying to act in advance of need. It is preventative to a large extent.[25]

1.34

Mr Tune also noted that most advanced countries are doing 'fairly

substantial fiscal stimulus programs at the moment'. The IMF recommendation or

view is that fiscal stimulus should be at least two per cent in calendar year

2009, which is around the figure of Australia's package.[26]

1.35

Officials were questioned as to whether a smaller package, $12 billion

or $21 billion, would not have achieved the same outcome. In response,

Treasury Secretary, Dr Ken Henry stated that the proposed $42 billion plan

would result in GDP growth whereas a smaller plan may well leave GDP contracting

in 2009–10:

... we estimate that as a result of this package...GDP growth will

be around half a per cent higher in 2008-09 and around ¾ to one per cent higher

in 2009-10. It follows, I think, that a smaller package, even a smaller package

with the same profile, would contribute smaller amounts to GDP growth in

2008-09, and with a package that had the same profile and the same composition

as this package—I know those are two big qualifications—but that had a lower

level, a lower aggregate amount, there would be some point at which GDP growth

in 2009-10 in particular might well have been negative.[27]

1.36

On the other hand, doubling the package amount would not necessarily

result in a doubling of the impact on GDP. Dr Henry also commented that 'one

would have to start worrying about the capacity issues':

As I indicated, this particular package takes account of

judgements that we and Finance have made about the capacity of the economy to,

if you like, digest these programs. If these programs, for example, were to be

doubled, maybe we would make different judgements about the capacity of the

economy to digest those programs in that same time profile. I suspect we would

and for that reason we should not expect the multipliers to be constant.

Therefore, you should not expect a linear impact.[28]

Government's Balance Sheet

1.37

A number of senators raised questions about the impact of borrowing on

the Government’s balance sheet. The Government will need to borrow to fund the Nation

Building and Jobs Plan to support the economy and jobs. However, the

Government's balance sheet remains in sound shape, particularly when compared

to other comparable economies.

1.38

As economist Mr Saul Eslake, stated 'the levels of public debt projected

in the Updated Economic and Fiscal Outlook are not excessive or alarming by

either Australian historical or international standard'.[29]

1.39

The UEFO forecasts that general government net debt will rise to 5.2 per

cent of GDP in 2011-12. This is around the average net debt levels that have

prevailed over the past three decades and compares to an average net debt

across OECD member countries of more than 45 per cent of GDP.

Composition of the package

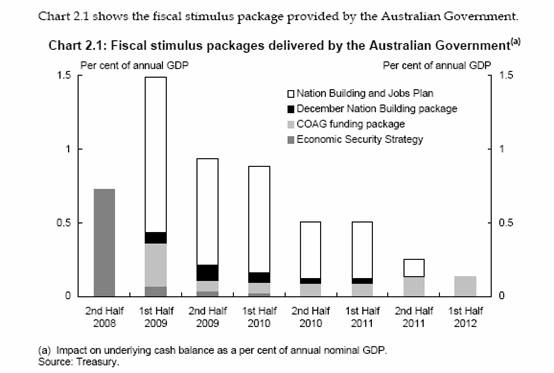

1.40

The UEFO provided a chart showing the projected impact of the package on

aggregate demand as well as the relative contributions of earlier stimulus

measures.[30]

1.41

The UEFO stated that as a result of the plan, GDP growth will be around

half per cent higher in 2008-9 and around three-quarters to one per cent higher

in 2009-10.[31]

1.42

There was considerable discussion during the inquiry concerning the

composition of the package. This went to the use of a tax bonus instead of tax

cuts (this is discussed in chapter 5) and the balance between the various

elements of the plan, including the timing of the impact.

1.43

Dr David Gruen, The Treasury, commented on the way in which the plan has

been framed:

We are in a very unusual situation, which is that Australia is

suffering from insufficient aggregate demand for the whole economy. So the

package has been framed with the thought in the backs of our minds that it is

important to come up with spending plans that will deliver stimulus to the

economy quickly—let us say over 2009 and perhaps into 2010. That is based on a

current assessment of what we think is the nature of the global recession;

namely, we think it is deeper, and will be longer, than we thought several

months ago. So we are focused on spending that will have a material effect on

demand within the economy over that sort of time frame. In assessing the

spending in this package, an important criterion is spending that will actually

have an impact on the economy relatively quickly, because that is the nature of

the problem that we are facing.[32]

1.44

Dr Henry reinforced the need for the plan to address immediate problems:

The problem we are dealing with at the moment...is that we are in

very unusual circumstances, quite unlike the circumstances we have been in the

last 10 years, in which the aggregate demand in the Australian economy is about

to fall dramatically below potential gross domestic product. This package is

about trying to minimise the extent to which aggregate demand falls below

potential gross domestic product. The reason for that is that... if aggregate

demand falls markedly below the potential level of gross domestic product, then

so too will the actual output in the Australian economy fall markedly below its

potential, and many people will end up unemployed.[33]

And:

The thinking that informed the development of this package was

that the current calendar year, 2009, is likely to be in the absence of any

fiscal stimulus a particularly weak year and to some extent also 2010. These

are the key years. That is true globally. You can see that in the IMF's

forecasts for world growth. Particularly 2009 is anticipated to be the weak

year but with some risk on 2010. So the advice that we provided to government

was that it would be appropriate to have a fiscal stimulus which in calendar

year 2009 was at least, at a bare minimum, one percentage point of GDP and

considerably more than that if it were feasible to develop a package that would

have that impact on government spending in calendar year 2009 with some amount

being spent in 2010. I guess it was that thinking about the shape of the

package which ultimately determined the size of its budgetary cost in each year

and its profile.[34]

1.45

This point was also noted by Mr David Tune, Department of the Prime

Minister and Cabinet:

The key focus was to try and get immediate stimulus. That is

what it is about, and that is why there was a mix there of cash payments,

including a tax offset, and infrastructure—mainly community infrastructure

because it is very fast to get going. The whole intent of this package is to

try and get stimulus during the course of 2009.[35]

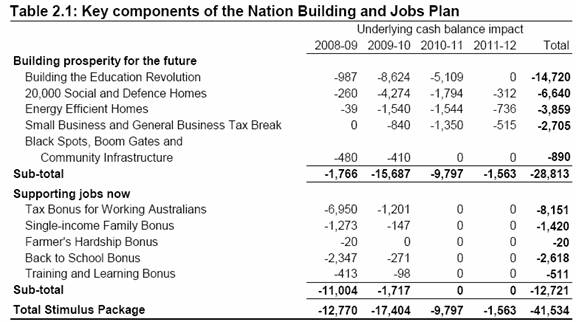

1.46

Table 2.1 of the UEFO provides the key components of the plan and impact

for the years 2008-09 to 2011-12. The impact of the capital projects lifts

after 2009-10 while direct payments to families have an immediate impact. The

implementation lag is shorter for direct transfer payments to households and

longer for direct government spending.

1.47

Dr Ian Watt, Secretary of the Department of Finance and Deregulation,

commented on the table and stated that:

The top group is the direct government spending. As you can see,

very little direct government spending occurs in 2008-09. With the best will in

the world, with the fastest-acting infrastructure, capital or repair and

maintenance programs that we could find, it was still extremely difficult to

spend much money in the next five months.

...

As you can see in the bottom panel on that table, the direct

payments to families and individuals impact on 2008-09 disproportionately by

comparison. So they give you the relatively rapid stimulus in 2008-09. The

capital projects, the repairs and maintenance projects, pick up steam through

2009-10.[36]

1.48

Dr Henry also explained:

The implementation lag is somewhat shorter for direct transfer

payments to households and somewhat longer for direct government spending. So

if one were to decide that on this occasion one was going to reserve for a

future period any decisions about measures impacting in, let us say, 2009-10,

for example, then when one came to make those decisions, one would be

confronting precisely this problem again. The problem with sequential decision

making is that it will never prove efficacious to deciding to undertake

activities that have an implementation lag longer than the period of time

between the two decision making points.[37]

1.49

In answer to questions on why there was a need to implement the plan in

one stage, rather than some parts at a later time if required, Dr Henry

commented:

Were decisions not taken now, very little of the impact that you

see in 2009-10 would be there. So if you want to have a fiscal impact in

2009-10 and you want that fiscal impact to be through direct government

spending—the measures which are in the top part of this table—then you have to

take the decisions now. If you leave it for another 12 months, for example, you

will not be able to have an impact in 2009-10 in respect of those measures.

Well, you will not be able to have much of an impact. The earliest you will be

able to have much of an impact will be 2010-11 and so on. You will be

continually pushing out for about a year the time at which those measures would

have an impact on the economy. There is an inevitable implementation lag. Is that

sufficiently clear—an inevitable implementation lag. You have to take the

decision and you have to be prepared to live with the implementation lag.[38]

1.50

A number of Senators raised the question of whether cash vouchers would

be a more effective means of ensuring immediate cash flow into the economy as

opposed to one-off cash bonuses.

1.51

In response, Dr Henry stated:

I am just trying to illustrate why there is a difficulty with

the voucher proposal—then surely a household that could only access the $950

through a voucher arrangement would simply spend that $950 and reduce spending

by an equivalent amount elsewhere in their income. That is, if you thought that

the whole $950 was going to be saved unless you had a voucher mechanism then

surely what the household would do is take the voucher, spend all the money and

save another $950 part of their income. To put it another way, money is

fungible.[39]

1.52

Treasury officials were questioned on the choice of measures in the

plan, particularly in relation to infrastructure projects including why

infrastructure projects that would overcome bottlenecks for the export industry

and spending on the Murray-Darling Basin were not included while spending has

been directed to assembly halls and sports centres. In response, Dr Henry highlighted

that such projects would not enable prompt infrastructure expenditure required

to address the deficiency of aggregate demand which the plan was specifically

designed to address.[40]

He further noted that:

I think rather the issue is: in dealing with the very rapid

decline in aggregate demand that we have in our forecasts, can that form of

infrastructure spending be brought online in a sufficiently timely fashion that

it can impact on aggregate demand now? Those infrastructure bottlenecks are worth

addressing, no matter what the macroeconomic circumstances are that Australia

is confronting. They should be judged on their merits as supply enhancement

initiatives. The government's consideration of those things, in my view—and

this is advice I would tender to any government—should not be affected by the

state of the macroeconomy. But those projects do not tend to be the sorts of

projects that can be brought on stream very, very quickly in order to address a

very rapid decline in aggregate demand. They tend not to be of that nature.[41]

1.53

Dr Henry made similar comments in relation to other infrastructure

projects raised in the evidence.[42]

Dr Henry also addressed the notion that there is 'a very large volume of

supply enhancing infrastructure projects out there on which government

expenditure could be undertaken tomorrow'. He commented that that is not the

case: 'It is obviously the case that there is a lot of infrastructure spending

that is being undertaken, but could that be doubled, tripled or quadrupled

overnight? No, I do not think it could be'.[43]

The multiplier effect of the plan's measures

1.54

Questions were raised during the inquiry as to the rationale of the

combination of measures proposed under the plan and the strength of the

multiplier effect of such measures.[44]

The Treasury indicated that the multiplier would be a half to one, but there

was uncertainty about the magnitude.[45]

Dr Gruen stated:

...our estimate of the fiscal multiplier is something like a half

to one, as in spending to GDP. We would like to be more precise than that, but

if you look at the literature, including papers produced by the IMF, that is

exactly the sort of range that people quote. We do not have these numbers to

the degree of precision that we or anyone else would like. We have estimates with

a range of the order of half to one for the multiplier.[46]

1.55

Dr Gruen continued:

We can make a broad comment on that which is that...we think it is

reasonable to expect that the multiplier on infrastructure spending is likely

to be higher than the multiplier on one-off payments to individuals. The reason

is that, if you spend a dollar, you have already put a dollar into the economy

whereas, if you hand a dollar over to someone, they may save part of that

dollar. You probably get a larger multiplier for infrastructure spending.[47]

1.56

Dr Henry noted that leakages, such as to savings and spending on

imports, occur and detract from the direct impact of the measure:

The bit that goes overseas is an income leakage. But the bit

that goes to Australian households, like the wages and salaries that go to

Australian households, some of it will be saved and some of it they will bring

back into the retail sector and you get that multiplier process.[48]

Employment

effects

1.57

Treasury officials noted that when economic growth is forecast to be

below trend, the unemployment rate is forecast to rise. The UEFO states that the

plan will help 'support and sustain' up to 90,000 jobs over the next two years

but 'notwithstanding the solid boost provided by the fiscal stimulus, the

unemployment rate is forecast to reach 7 per cent by June 2010'.[49]

1.58

Treasury indicated that the figure of 90,000 was based on 'an estimate

of how much we think the package will raise GDP and then from there we use an

employment equation to give us an estimate of what increase in employment that

will lead to, relative to not doing it'.[50]

Dr Henry commented:

...to the extent that one can minimise the number of people losing

a job, the better the prospects are of those people going forward being able to

find a job—that is, the greater the extent to which one can minimise the number

of people who lose a job, the smaller the period of time for which those people

might find themselves out of work.[51]

1.59

Dr Henry concluded that the 'biggest risk to unemployment in Australia

is the deficiency of aggregate demand emerging'.[52]

The plan is aimed at increasing aggregate demand which will impact positively

on employment. Mr Tune also commented that:

This package does protect jobs; there are no two ways about

it—it supports jobs. There are issues there about other people who will lose

jobs. Yes, that is what happens in these sorts of situations. The existing

income support system is there to assist those people. The Job Network is there

to assist those people. Both those programs are demand driven, so there is no

dollar constraints on whether people can gain access to those payments or gain

access to the services of the Job Network. So all of those things are there.

The Prime Minister said yesterday that in conjunction with the states he would

like to work through what more can be done in those particular areas. So that

is an issue under active consideration at the moment.[53]

1.60

In response to concerns raised about a rise in unemployment, Mr Grant Belchamber

of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) stated:

The package as a whole is directed at supporting economic

activity and avoiding the increase in unemployment that would otherwise occur.

The cash payments are at the front end of the package, with the infrastructure

spending to follow on from them. We think both parts are absolutely critical in

assisting currently unemployed Australians to find work and in preventing job

losses amongst currently employed Australians. On the whole, the package

delivers substantially in the interests of unemployed Australians and those

employed in firms that find the going tough over the coming year.[54]

1.61

Mr Frank Quinlan representing major Church providers noted of the plan:

The Rudd Government's Nation Building and Jobs Plan is not

designed as a rescue package for the community sector or for unemployed people.

It is a rescue package for the nation as a whole which focuses on creating and

maintaining jobs.[55]

1.62

Whilst Ms Hatfield Dodds of the Australian Council of Social Service

(ACOSS) raised concerns about assistance to the unemployed, she stated that

ACOSS supports the plan for seeking to 'prevent unemployment from rising even

more rapidly'.[56]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page