Chapter 2 - Regional Partnerships Program

2.1

The Regional Partnerships (RP) program, which commenced

on 1 July 2003, is intended

to give effect to the government's policy set out in the publication, Stronger Regions, A Stronger Australia.

RP replaced eight precursor programs, the Regional Solutions, Regional

Assistance, Rural Transaction Centres, and Dairy Regional Assistance programs

and four regional structural adjustment programs.[26] As noted in Chapter 1, the funding of

a project under one of those programs, the Dairy Regional Assistance Program,

was the subject of a previous Finance and Public Administration References

Committee report.[27]

The RP program

2.2

Detailed information on the RP program may be found in DOTARS'

submission to the inquiry.[28] That

submission includes a number of attachments that describe all facets of the

program, including, among other things, the guidelines for determining

successful projects, the constitution and role of the 56 Area Consultative Committees

(ACCs) that act as advisory bodies in the regions, and the role of the minister.

Only some of these matters are discussed in this chapter. Issues related to the

ACCs are discussed in the next chapter. Information about the program may also

be accessed on the DOTARS Regional Partnerships website.[29]

2.3

In this chapter, the Committee outlines aspects of the

structure and operations of the RP program which are critical to understanding

how the program works and which are relevant to some of the case studies

examined later in the report. These aspects are:

-

Guidelines

-

Strategic Opportunities Notional Allocation

(SONA)

-

The minister's role

-

Expenditure, including election commitments

-

Distribution of grants

-

Administrative processes

-

Funding agreements

-

The TRAX system

-

Audit and evaluation.

The RP guidelines

2.4

The guidelines cover matters such as the aims of the

program, the involvement of the ACCs and local government, accountability

requirements and advice about how to apply for a grant. Other matters covered,

and those elements of the guidelines which proved to be of most relevance to

the inquiry, are assessment criteria and the eligibility of organisations and

projects.

2.5

The guidelines were first published on the DOTARS

website towards the end of June 2003, and have been revised since then.[30] It is not clear when the revision was

made, but it apparently involved a change to the eligibility criteria, in

particular to the need for a project to have the necessary approvals and

licences in place for it to be approved.[31]

This is discussed below in relation to eligibility for funding and is particularly

relevant to the Tumbi Creek project discussed in Chapter 5.

Assessment criteria

2.6

The guidelines provide that:

To ensure the most effective use of Regional Partnership funds,

priority will be given to those projects that demonstrate value for money by

achieving their outcomes through the most efficient and effective means,

securing appropriate funding from other sources and/or have exhausted other

funding options.

Value for money will be determined taking into account the total

request for Regional Partnerships funding and meeting the...assessment criteria.[32]

2.7

The RP guidelines set down several assessment criteria

under three headings, namely, outcomes,

partnerships and support and project and applicant viability.

2.8

Under outcomes

the guidelines specify that a successful project would demonstrate that it

would provide benefits to the community by, for example, meeting a demonstrated

need or community demand for the project's

outcomes. A successful project would also demonstrate that it would create or

enhance opportunities in the community by, for example, providing

infrastructure that enhances economic/social opportunities.[33]

2.9

Under partnerships

and support the guidelines state that establishing community support is

critical to the long-term success and ownership of a project. The guidelines

define the ways in which it may be demonstrated that a project is a partnership

and that it has community support. The guidelines read as follows:

Partnerships are a strong demonstration of support. Partnerships

are established where individuals, private sector businesses, community/not for

profit organisations, other organisations and any local, state and/or

Australian Government agencies make a financial and/or in-kind contribution to

your project.[34]

2.10

Under project and

applicant viability the guidelines set down several criteria, including the

demonstrated ability, or access to expertise, to manage the project both during

and after funding and demonstrated sustainability beyond the funding period.[35] The sustainability criterion is of

some significance in the Tumbi Creek case study included in Chapter 5.

Eligibility

2.11

With some specified exceptions, entities registered

under State or Commonwealth legislation, for example the Corporations Act 2001, can apply for Regional Partnerships funding.

The exceptions include Australian and state government departments, individuals,

and private enterprises and co-operatives that are considered commercial

enterprises that are requesting funding for planning, studies or research.

2.12

ACT Chief Minister Mr Jon Stanhope MLA submitted that

the RPP eligibility criteria disadvantage the ACT. All ACT government

departments are ineligible to apply for funding despite the fact that the ACT

government performs both state and local government functions:

This approach unfairly disadvantages the ACT. The ACT government

is unique in Australia

in that it delivers both State/Territory and local government functions. While

other local governments in Australia

can apply for RP program funds, the ACT cannot.[36]

2.13

The Committee considers that these concerns are valid

and that ACT government departments should be allowed to apply for funding for

projects that would otherwise be eligible under the RPP guidelines.

2.14

The guidelines identify a number of different types of

project that would not be eligible for funding. Ineligible projects include

those that compete directly with existing business, unless production

differentiation tests can be met,[37]

and those that could involve cost shifting or that duplicate funding from other

sources. The guidelines also specify that proposals that cannot obtain, or have

not yet obtained, the relevant approvals or licences to progress will not

generally be considered. They also specify that retrospective costs cannot be

funded.[38]

2.15

The guideline regarding the need for a project to

obtain relevant approvals or licences gave rise to some confusion during the

inquiry because the version of the guidelines on the DOTARS website contained

contradictory requirements. The current guideline is reproduced in the

paragraph above. The version of the guidelines on the website included that paragraph,

but also specified that projects that 'could

not obtain or were in the process of obtaining the relevant approvals or

licences to progress' were not eligible for funding.[39] This contradicts the above statement

that such projects will not generally be

considered.

2.16

The eligibility criteria are particularly significant

with regard to the Strategic Opportunities Notional Allocation procedures that

are discussed below.

Strategic Opportunities Notional Allocation (SONA)

2.17

Some funds within the RP program are 'available each

financial year for new projects that are seen as strategic opportunities'.[40] According to the RP Internal

Procedures Manual, SONA 'will allow the Government to respond quickly and

easily to a diverse range of situations which may fall outside the

administrative constraints of RP, but which are consistent with the purposes of

RP'.[41]

2.18

The SONA procedures provide that the projects and initiatives

that are administered under the procedures need to be consistent with the goals

and priorities of either Regional Partnerships or the Stronger Regions, A

Stronger Australia

statement, and that they must meet the majority of the RP program's

selection criteria. The DOTARS procedures identify three categories of project

that could be considered under SONA, as follows:

-

projects that are of national or cross-regional

significance;

-

projects that are a whole-of-government

response; or

-

projects that respond to a significant event,

such as a regional economic or social crisis, where relief is not available

from existing relief programs.[42]

2.19

The document also states that SONA procedures may

address program restraints of a more administrative nature, and the following

examples are given:

Where funding for a high priority project would significantly

exceed the relevant ACC's notional allocation and approval cannot be delayed

until sufficient RP funding becomes available; or

Where a decision not to support a project is reversed following

formal review and additional funding flexibility is required; or

Where a project or initiative would require the waiver of some

specific part of the guidelines or eligibility criteria in order to be funded

(eg the waiver that enabled normally ineligible proponents, Australia Post and

Centrelink, to participate in Rural Transaction Centres).[43]

2.20

The SONA procedures appear to have been applied to nine

projects in the 18 months to 31

December 2004. Six of those projects were approved for funding, as

follows:

-

Christmas Island Mobile Upgrade, Christmas Is. -

$2.750 million

-

Crocfest, Commonwealth Department of Health and

Ageing - $158,400

-

Primary Energy Pty Ltd, Gunnedah, NSW - $1.210

million

-

National Centre of Science, Information and

Communication Technology, and Mathematics for Rural and Regional Australia

(SiMERR), University of New England, Armidale, NSW - $4.950 million

-

Slim Dusty Foundation Ltd, Kempsey, NSW – 2

grants of $550,000

-

Sugar Industry Reform Package, national -

$12.734 million.

2.21

Three projects were rejected, namely, Regional Australia

on Board (West Melbourne), Wholesale Regional Banking Model Development (Kingaroy,

Qld) and the CISSES (Chain of Intermodal Shared Services on the Eastern

Seaboard) Consortium, that was proposed by the Wagga Wagga City Council. The

reason given for rejecting the West Melbourne proposal

was given as, 'Poor value for money for program funds. RP is not the most

appropriate funding source for this activity'.[44]

The reason for rejecting the regional banking proposal was, 'Suitable partner

funding and/or community support not demonstrated. Sustainability and/or wider

community benefit of outcomes not demonstrated'.[45] The CISSES proposal, which aimed to

create an efficient freight system across eastern Australia,

was rejected on the grounds that, 'Sustainability and/or wider community

benefit of outcomes not demonstrated'.[46]

2.22

DOTARS informed the Committee that in the 2003-04

financial year $20.872 million was committed to SONA. The major projects for

which funds were committed in that year were the sugar industry reform package,

SiMERR and the Christmas Island mobile upgrade. When the

SONA procedures were produced in September 2003, $3 million was allocated for

2003-04 for SONA,[47] suggesting that

the government did not expect that SONA would be used as extensively as it was.

The actual commitment of funds under SONA in 2003-04 suggests that the

allocation was indeed 'notional'.

2.23

One of the RP program's

predecessor programs, the Regional Assistance Program (RAP), also included

provisions for grants for projects of national significance. The Australian

National Audit Office (ANAO) conducted a performance audit on the administration

of the RAP, including the Projects of National Assistance elements of the

program, in 2002.[48] DOTARS informed the Committee that:

SONA was modelled to satisfy the principles set for the Regional

Assistance Program Projects of National Significance.

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) Report on the Regional Assistance Programme agreed to the concept

of the Projects of National Assistance elements of that programme and made a

number of observations regarding consistent decision making and public

accountability, in particular that 'the

assessment process should be sufficiently rigorous to provide reasonable

assurance that the projects selected are consistent with the guiding principles

of RAP'.[49]

2.24

DOTARS stated that the projects that had been administered

under the SONA procedures of RP did not meet the usual eligibility criteria. DOTARS

also stated that only three of the eligibility criteria had not been fully met.

The relevant criteria were the provision of funds to other government

departments, the use of a grant to produce a prospectus and the lack of

planning approval for a project.

2.25

Dr Gary

Dolman, Assistant Secretary of DOTARS

Regional Communities Branch, informed the Committee that the Slim Dusty project

in Kempsey, NSW, did not have full planning approval when it was approved, but

that the RP guidelines had been amended since then so that the project would

now be eligible for approval under the normal arrangements for RP projects.[50] The Committee finds this explanation

unsatisfactory. The fact that the guidelines were later amended does not excuse

the fact that this project was approved without meeting the guidelines.

Applications must be assessed against the guidelines in place at the time to

avoid making a mockery of established processes.

2.26

It is interesting that the two grants to the Slim Dusty

project that were administered under the SONA procedures were approved on 25 January 2004 and 21 June 2004. A project for the dredging

of Tumbi Creek in New South Wales

was approved on 24 June 2004,

having been administered under the normal RP arrangements, despite the lack of

the appropriate licences. The administration of the grants for the dredging of

Tumbi Creek is described in detail in Chapter 5.

2.27

Another RP grant that was processed under the SONA

procedures is a $1.2 million grant to Primary Energy Pty Ltd for the 'grains

to ethanol' project. That project also had to

be administered under SONA because it did not meet the RP eligibility guidelines.

The grant was in fact approved for planning purposes and for the production of

a prospectus, contrary to the guidelines.[51]

The Primary Energy grant is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7. A grant to

the University of New England for the SiMERR project also was administered

under SONA, not only because it was of national or cross-regional significance,

but also because it may have breached the partnership criteria in as much as

the hub centres in the other States and Territories (partners in the project) were

not confirmed at the time the grant was processed.[52] This grant is also discussed in

Chapter 8.

Publication of the SONA procedures

2.28

The SONA procedures were first produced in September

2003, some weeks after the RP program was established, and were revised in

March 2004.[53] Unlike the RP guidelines,

the procedures were not published widely but were included only in the Internal

Procedures Manual. In effect, until the SONA procedures were tabled in the

House of Representatives in early December 2004, in response to intense

scrutiny by the Opposition, the only persons with access to them were DOTARS

employees in the relevant area and (potentially) employees and members of the

Area Consultative Committees. The procedures apparently were not known to those

who might have made applications for grants and, more importantly, were not

known to parliamentarians whose role it is to scrutinise government expenditure.

The SONA procedures were provided to the Committee in DOTARS' submission

(attachment H).

2.29

It became evident during the course of the inquiry that

many ACC chairs and executive officers were still unaware of the existence of

the SONA procedures.[54] Four ACC

executive officers (EOs) told the Committee they were aware SONA existed

because Ms Riggs,

DOTARS Executive Director, Regional Services, had mentioned it at an ACC EO's

conference, but none of them had ever seen the procedures.[55]

Administration of SONA

2.30

DOTARS submitted that projects administered under the

SONA procedures are 'assessed in the normal way, including against the Regional

Partnerships' assessment criteria of clear outcome, partnership, benefit to the

community and sustainability'.[56]

2.31

Despite evidence from DOTARS to the contrary,[57] it is clear that ministers' offices

were involved in decisions to apply the SONA procedures to certain projects.

DOTARS' submission states that ministers have not directed or suggested to

departmental employees that the procedures be applied to an application.[58] However, as described in the Primary

Energy case study in Chapter 7 of this report, the department was subject to

pressure from Minister Anderson's

office and a strong request from another minister that the project be funded.

It is obvious that DOTARS had no option but to use the SONA procedures to give

effect to that request.

Role of the minister

2.32

The RP program is one of many discretionary grants

programs administered by the Commonwealth Government. A consequence of the

discretionary nature of the program is explained in the guidelines published by

DOTARS, as follows:

Regional Partnerships is a discretionary programme. The funding

of projects, through Regional Partnerships, is at the discretion of the Federal

Minister for Transport and Regional Services or the Federal Minister for

Regional Services, Territories and Local Government, therefore meeting the

assessment criteria does not guarantee funding.[59]

2.33

A corollary to this is that the ministers may approve

projects that do not necessarily meet the guidelines or that they may vary the

amount of the grant. DOTARS informed the Committee that in relation to 17 or

three per cent of the approximately 600 applications processed by the

department from 1 July 2003

to 31 December 2004, the minister

did not follow the department's recommendation.

Of the 17, the minister approved 11 projects that the department advised should

not be approved, rejected three that the department considered should be

approved and in three cases the minister varied the amount of the grant from

the department's advice.[60]

2.34

The Committee requested DOTARS to identify those

projects on which the minister's decision deviated from the department's

recommendation, but departmental witnesses refused to provide this information.[61]

2.35

The discretionary nature of RPP funding decisions,

combined with this refusal to disclose details of the minister's decisions,

leaves the RP program susceptible to perceptions of bias. Submissions to the

inquiry suggested that such perceptions could be overcome by appointing a board

or commission to undertake RPP funding decisions.

2.36

Mr Jon Stanhope MLA, ACT Chief Minister, submitted:

Given the accountability of Ministers, it is not unreasonable

for Ministers to make the final decisions on funding projects. However, the

Regional Partnerships program's broad guidelines allows it the flexibility to

support a wide range of projects under its banner. In this case, the rationale

for approving particular projects in particular locations may not be as clear

as in programs with more tightly defined objective and guidelines.

To overcome any perception of bias in supporting projects, the

Australian Government could consider moving the responsibility for approving or

rejecting projects to a government appointed board with members who had

relevant qualifications.[62]

2.37

Mr Stanhope

suggested that the approach used by the former Networking the Nation program

would provide a suitable model for RPP. Mr

Peter Andren MP

suggested that a grants commission process similar to that used to allocate

local government grants would be a suitable approach.[63]

Expenditure

2.38

The Commonwealth Government spent $86.922 million on

the RP program in 2004-05, and has appropriated $111.625 million for the

program in 2005-06. It is estimated that a further $250 million will be

allocated to the program from 2006-07 to 2008-09.[64] Including the $78.457 million expended

on RPP in 2003-04,[65] the total amount allocated

to the program exceeds $500 million.

2.39

In the period 1

July 2003 to 31 December

2004, the minister approved funding for 504 projects, to the value

of $123,656,940.[66] The minister also

rejected 150 applications for funding in that period.[67] The amount of grants approved for projects

ranged from $2,754 for replacement lighting for tennis courts at

Brushgrove, New South Wales, to $12.734 million for 'transitional support for

the sugar industry and consequently to sugar dependent communities'.[68]

Election commitments

2.40

Not all the funds allocated for the RP program in

2005-06 and future years will be expended on new RP projects or on projects now

in the process of assessment. A significant number of election promises were

made that will likely be met from the program funds. DOTARS submitted a list of

these promises and their expected cost. There are six 'icon' projects, for

which $27.5 million has been promised, and 50 other projects.[69] The cost of the election commitments

likely to be funded through RP amounted to approximately $66 million, ranging

from a grant of $5,000 for the Macedon Football Club to upgrade its change

rooms to $15 million for a Rural Medical Infrastructure Fund.

2.41

Proponents of some of the projects in the list may have

been in the process of applying for grants and may have met the guidelines for

receiving a grant. However, apparently there is no need for any of the projects

identified as election promises to address the RP guidelines in order to

receive a grant from the program. DOTARS informed the Committee that instead of

the normal application process, the department would seek information from each

of the proponents to enable it to make an assessment of risk to the

Commonwealth. Ms Riggs

stated that:

We will then formally put an advice to the minister or

parliamentary secretary in respect of each of these projects. That might, for

example, say that there might be some conditions on the funding, and only then

would we seek to enter into a funding agreement which would convert those

commitments into actual grants. [70]

This demonstrates that the process of funding election

commitments from RPP was neither transparent nor rigorous. Some effects of

election commitments bypassing the RP guidelines and assessment processes are

discussed below in relation to commitments made in Tasmania.

Effect of RP election commitments in

Tasmania

2.42

A total of $1.535 million in election commitments to be

funded under RPP were made in the electorate of Bass in Tasmania,

suggesting that the seat was targeted by the government at the 2004 election.

Projects included $600,000 for economic development initiatives in Launceston

and Northern Tasmania, $150,000 for a planning strategy

for the town of Bridport, $250,000

for bicycle tracks in Launceston and $250,000 to develop a complex in Georgetown

to house the Bass and Flinders replica ship, 'The

Norfolk'.[71]

A total of $2.765 million of election commitments to be funded by RPP in Tasmania

were made during the 2004 election period.[72]

2.43

In his submission to the inquiry, the Hon

Paul Lennon MHA,

Premier of Tasmania, raised a number of concerns about the effects of the federal

government's election commitments to be funded

from the RP program. The impacts included election commitment projects

duplicating state programs relating to recreational infrastructure and matched

funding requirements being placed on the state government.[73] The Premier commented as follows:

The funding will be provided on the proviso that the State

Government matches the funding. This raises a number of issues, in particular:

- The capacity to deliver additional projects;

- "Matched funding" requirements being imposed

on the State Government;

- Duplication between the program's projects, and those

that are State funded; and

- The consideration given to the local context when

deciding funding.[74]

2.44

The Premier's

submission also commented on the election promises bypassing the program's

established processes and undermining the consultation requirements integral to

RPP:

The projects promised during the election have involved minimal

consultation with TEAC [ACC Tasmania] and the State, and undermine the

systematic processes of the partnership program that was established by the

Commonwealth.[75]

2.45

The Committee received similar evidence from ACC

Tasmania that election commitments raised questions among proponents who had

followed the proper process:

The "election promises" where projects have received

funding, that were not known to the ACC, or where further development was

required, undermines the voluntary commitment of the ACC Regional Directors...The

Regional Directors are the face of the ACC in regional communities, therefore

they are approached by community members...[who ask] "why projects were

funded" when they were informed of the correct procedures and process

which had to be adhered to for funding under Regional Partnerships.[76]

2.46

The Committee considers that the government should take

existing state and local government programs and priorities into account and

consult with local ACCs before making election commitments.

Distribution of grants

2.47

DOTARS submitted data up until 31 December 2004 showing the distribution of

grants by political party and location of electorate.[77] The data show that overall there was

little difference in the proportion of applications approved among electorates

held by different parties. There were, however, significant differences in the

numbers of applications made from electorates held by Government, Opposition

and Independent members and in the funds provided.

2.48

In the 82 electorates then held by the Government, 795

applications were made resulting in $65.2 million of grants. In the 64

electorates held by the Opposition, 209 applications were made resulting in

$18.5 million of approved grants. In the 4 seats then held by

Independents/minor parties, 60 applications were made receiving $14.9 million

in approved grants.

2.49

Differences in the number of grants and funding

received were also apparent across the locations of electorates. In the 38

metropolitan electorates held by the Government parties 58 applications were

made. In the 50 metropolitan electorates held by the Opposition, 96

applications were made. The Government-held electorates received a total of

$6.9 million while the Opposition-held electorates received $4.5 million.[78]

2.50

In provincial electorates the Opposition held eight

seats, from which 67 applications were made, resulting in grants valued at $7.5

million. From the eight seats held by the Government parties there were 44

applications, which led to $3.2 million in grants.

2.51

In the rural electorates the differences were more

marked. In rural locations, 46 applications were made from the six seats held

by the Opposition, and those electorates received $6.5 million in grants. There

were 693 applications from the 36 electorates held by the Government parties,

and $55.2 million in grants. The three seats in this category that were held by

Independents received $14.6 million from 54 applications (this amount

presumably included the $5.5 million made to the Buchanan Park 'icon' project.)

2.52

While there is no 'average' electorate, and hence no

reason why there necessarily should be equity in the distribution of grants

among electorates, the average amount in grants provided to each electorate may

be instructive. When considering these figures, it should be remembered that

the RP program is intended to benefit the regions. It should also be remembered

that the figures are for grants approved, not for funds committed.

2.53

In the metropolitan areas, each electorate held by the

Government parties received an average of $180,614 while each electorate held

by the Opposition received $90,999. In provincial areas, Government-held

electorates received on average $395,278, while Opposition-held electorates

received $938,828.

2.54

For electorates in rural locations, the average amount

of RP funding approved for Government-held electorates was $1.5 million and was

$1.1 million for seats held by the Opposition. The three electorates held by

Independents received on average $4.9 million. These electorates include New

England which was described as a 'National Party target seat'.[79] Issues surrounding some significant

grants made to projects in that electorate are discussed in Chapter 8.

2.55

In summary, the overall number of grants approved for

Government-held seats was significantly higher than for Opposition-held seats.

The electorates that on average received most funding from the RP program were

seats held by Independent members.

Distribution of SONA grants

2.56

As noted above, six projects were approved using the

SONA procedures in the 18 months to 31

December 2004. One of these projects, the Christmas Island Mobile

Upgrade for $2.75 million, was located in an Opposition-held electorate. Two grants

totalling $1.76 million were for projects located in National Party electorates

—

the Slim Dusty Foundation and Primary Energy grants. The grant to the University

of New England SiMERR National Centre

for $4.95 million was to an Independent electorate. The remaining two projects

approved using SONA, Crocfest and the Sugar Industry Reform Package, were both

described as national projects and related to a number of electorates.

Timing of grant approvals

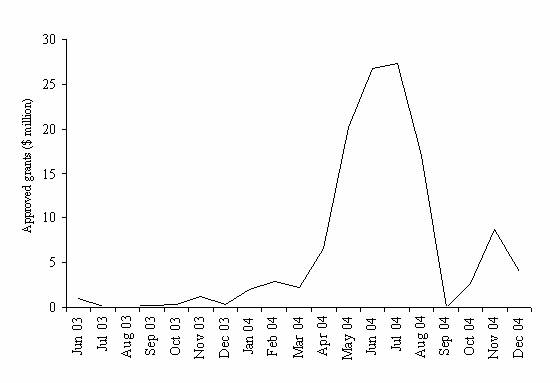

2.57

The number of project applications and quantity of

grants approved was not uniformly spread throughout the period to December

2004. As shown in Chart 1, there was a significant increase in grant approvals

in the months leading up to the 2004 federal election. In June,

July and August 2004, the three months preceding the announcement of the

election, $71.1 million worth of grants were approved. In other words, over half (58 per cent) of the total

funding approved for the entire period from the commencement of the program to

31 December 2004 was approved in the three months preceding the election

announcement. Of the funding approved in those three months, $22.1 million (31

per cent) was for projects in marginal electorates.

Chart

1: RPP grant approvals[80]

Administrative processes

2.58

Project proponents may lodge their applications with

DOTARS. Depending on the medium used, for example, electronic or paper, the

application will go either to the national office or a regional office. If an

application is lodged with DOTARS national office it is usually assigned to a

regional office for processing. The regional office refers the application to

the relevant Area Consultative Committee (ACC) for review.[81] The role of the ACCs is described in

more detail in Chapter 3.

2.59

Proponents are advised, for example on the RP website,

that before making an application they should contact the local ACC which can

assist them in developing their application, and with lodging it with DOTARS.

The ACC is required to consider the application, among other things, against

priorities in the relevant Strategic Regional Plan and against RPP's objectives

and criteria. The ACC is required to rate the project on a scale of 1 to 4,

with 4 being the highest rating.

2.60

However, the Committee received evidence, discussed in

later chapters, that in reality the processes described above are not always

followed. The Committee became aware of a number of applications that were not

forwarded to the ACCs for review, or where ACCs were given insufficient time to

consider and rate applications. Overall, the Committee is not in a position to

ascertain how often ACCs are excluded completely from the assessment process or

their role is minimised. This is unsatisfactory. The Committee was impressed by

the overwhelming majority of ACCs that it met and considers that the ACCs

provide an important reality check on project applications.

2.61

Applicants are contacted by the regional office to

provide them with preliminary advice, for example, to seek additional

information, or to inform them that their application is being assessed or if

it is ineligible.[82] If the project is

eligible for a grant and the application has been completed properly, it is

assessed in a regional office against a detailed checklist contained in the RP Internal

Procedures Manual. The application then goes through a 'quality assurance'

check at the national office, which is also responsible for the final

submission to the minister.

Announcement

2.62

After an application receives ministerial approval, the

grant is announced. The Internal Procedures Manual states that it is the

minister's preference for local (i.e. government) MPs or senators to have the

opportunity to advise successful applicants on behalf of the government. They

are also given the opportunity to make arrangements for the announcement. Two

or three days later the minister's office advises the successful applicant and

the relevant ACC. Non-government local members are also informed.[83]

2.63

A possible consequence of the early notification to government

parliamentarians is stated in DOTARS' procedural manual:

This means that DOTARS may find that applicants and ACCs are

aware that a project is successful before staff in either National Office or

Regional Office have been notified. This situation should be managed by DOTARS

staff tactfully.[84]

2.64

When DOTARS becomes aware of the announcement, summary

information about the recipient, the amount of the grant, the purpose of the

grant and the title of the relevant ACC are placed on the RP website.

2.65

For unsuccessful projects the relevant DOTARS regional

office notifies the applicant in writing within two weeks of the ministerial announcement.

Unsuccessful applicants may appeal to the department for a review of the

decision. Reviews are conducted by officers other than those who originally

assessed the application. A final decision on a review rests with the minister.[85]

2.66

The Committee wished to inquire into the timing of

grant announcements in comparison to the dates approvals were made. DOTARS,

however, declined to provide information about the date of announcements, despite

the Committee requesting this information in late 2004. As mentioned above, DOTARS

asserted that announcements are a matter for the minister, and DOTARS may not

necessarily know when announcements are made.[86]

Official openings

2.67

The RP Internal Procedures Manual includes advice about

official openings or launches. The decision maker or a representative of the

decision maker is invited. Representatives may be the local member (if a

government member), a 'patron'

senator or, if those persons are not able to attend, a representative from the

ACC or from DOTARS.[87] No mention is

made in the manual of invitations to non-government parliamentarians. This was

a matter of concern to the Independent Member for New England

in relation to his not being invited to the opening of an aged care facility in

his electorate. His concern is addressed in Chapter 8 of the report.

Due diligence

2.68

The due diligence that is conducted at least in

relation to an application for larger RP grants seems to take account of two

factors—the viability of the proponent and the viability of the project. Dr

Dolman, when commenting on the Tumbi Creek

project, defined due diligence as meaning whether or not the proponent is

likely to be facing financial difficulties and whether the project is viable.[88] This is a much weaker definition than

the statement in the RP guidelines that 'Applications

will be subject to substantially higher levels of scrutiny where it is

[sic]...seeking more than $250,000 from Regional Partnerships'.[89]

2.69

There was discussion during the inquiry regarding the

appropriate level of due diligence that is required, and also regarding when in

the assessment process due diligence should be undertaken. The executive officer

of the Far North Queensland Area Consultative Committee (FNQACC), when

commenting on investigations into the viability of the A2 Dairy Marketers

proposal, and responding to a question as to whose role it is to undertake due

diligence, stated that:

Let us be very clear about our understanding of what due

diligence is ... Our [FNQACC's] thing is to look

at it [a project] and make a balanced recommendation on what we believe. We

certainly do not have the resources..., with a staff of three, to be doing due

diligence...but it is within our scope to make some comment about what we see.[90]

This matter is further discussed in Chapter 6.

2.70

Despite some confusion about due diligence

responsibilities between ACCs and DOTARS, the RP Internal Procedures Manual

states that responsibility for due diligence rests with the department.[91] Due diligence seems to be conducted in

the main after the approval process, and for larger grants is usually

outsourced to external consultants. The RP Internal Procedures Manual advises

that a standard procedure before signing a funding agreement is the undertaking

of risk assessment processes. The amount of funding being sought, the project

type and applicant type determines the extent of the assessment. The following extract

is taken from the manual:

-

Pre-assessment – Basic check on an applicant (In

house)

-

Level 1 – Credentials check on an applicant

(Lawpoint website)

-

Level 2 – Assessment of applicant's financial

risk status (External consultant)

-

Level 3 – Assessment of project's commercial

risk/suitability (External consultant)

-

Private sector applicants are typically subject

to a higher level of risk assessment.[92]

2.71

The extent of due diligence then depends on the

proponent, and the size and nature of the project. The Committee was told by

DOTARS witnesses, for example, that local government councils as proponents are

generally assessed as being low risk.[93]

Ms Riggs

commented that:

Prima facie, for example, one might take the view that a council

is not going to be allowed to go broke by its state government, whereas that

would be unlikely be true of a private sector organisation. So you might allow

for a larger project or a larger amount of grant funding to go to a council

than you would allow to a private sector organisation without doing a very

intensive due diligence on the project that is in question.[94]

2.72

The Committee was hindered in its ability to examine due

diligence procedures because the thresholds for determining the level of due

diligence had been removed from the version of the RP Internal Procedures

Manual provided to the Committee by DOTARS. The following explanation for the

absence of the Assessing Risk and

Viability section was provided within the manual:

This section is currently under major review and therefore has

been removed. If advice is necessary contact the Applications, Approvals and

Contracts section.[95]

2.73

In contrast, the thresholds for the level of due

diligence required in relation to SRP projects were clearly specified in

DOTARS' submission:

-

A Lawpoint check for applicants seeking funding

of approx <$50,000

-

A company viability check for applicants seeking

funding of approx $50,000 - $500,000

-

A company and project viability check for

projects over $500,000.[96]

2.74

The Committee is disturbed that procedures fundamentally

important to determine the viability of projects and the risk to the

Commonwealth were left in abeyance without appropriate interim measures. The

Committee considers that guidance on due diligence checks should be finalised

as a matter of urgency.

Funding agreements

2.75

Grant recipients are

required to enter into a funding agreement with the Commonwealth.[97] The form of the agreement may be found

on the Regional Partnerships website.[98]

2.76

DOTARS, through its regional offices, negotiates with

the recipient regarding the budget, outcomes and milestones information that

are to be included in the agreement. The first grant payment is not made until

all the conditions that have been imposed on the approval of the grant have

been met, and further payments are not made until the recipient meets the

milestones specified in the agreement. As a result, the announced grant may not

be funded, as in the case of A2 Dairy Marketers, for example, which went into

receivership before the funding agreement was concluded.[99] In contrast, the first payment of

$426,800 to Primary Energy Pty Ltd was made conditional on merely signing the

funding agreement, and therefore no progress was required towards actual

project outcomes.[100]

2.77

In signing the agreement, recipients acknowledge that

the government may be obliged to disclose information contained in it.[101]

2.78

The Committee received copies of a number of agreements

relating to grants that it wished to consider in depth. The agreements were

detailed, and included, among other things, provisions for the management of

funds, record keeping and reporting. The Commonwealth's

agreement in relation to The Cove Caravan Park, for example, included among its

provisions 'activity/ milestone descriptions'

and 'expected reporting dates'

against those milestones. An example from the agreement reads as follows:

| Activity/milestone

description |

Expected reporting date |

| (iii) Kerbing/sealing roads and footpaths |

30

April 2005 |

2.79

The agreements state that recipients must provide

DOTARS with reports on progress at specified times. Post activity reports that

include audited statements of receipts and expenditure are also required.

2.80

An interesting inclusion in the agreements is a

standard provision, titled Acknowledgement

and Publicity, which requires the recipient to acknowledge the financial

and other support received. The agreement stipulates that any publicity should

use the words, 'This project is supported by funding from the Australian

Government under its Regional Partnerships programme'.[102] The provision also requires the

grant recipient to clear all publicity, announcements and media releases through

a departmental contact officer before they are released to the media.[103]

TRAX

2.81

A software system known as TRAX is integral to the administration

of the RP program. DOTARS submitted copies of diagrams from its TRAX training

manual that show that every step in the processing of a RP grant, from the

lodging of an application to the acquittal of funds, is recorded in the system.[104] DOTARS claimed that the use of TRAX addresses

a part of a recommendation made by this Committee in its report on a Dairy RAP

project, namely, that DOTARS 'adopt...an improved documentary record of

assessment procedures'.[105]

2.82

The department bought the basic TRAX product in

December 2002. It began operating in July 2003 and, by 30 June 2005, DOTARS had expended $3.8 million developing

and refining the system.[106] The costs

included two trips to Canada

by senior departmental staff to meet with the software providers to discuss

issues and problems associated with the development of TRAX.[107]

2.83

One witness, the executive officer of the Kimberley

ACC, claimed that TRAX is 'difficult,

time-consuming, customer unfriendly and it should not he released until all the

bugs have been removed'.[108] Ms

Riggs agreed that when DOTARS first released

the application 'front end'

of TRAX it was very user unfriendly, quite problematic and had some

limitations.[109] She informed the

Committee that because some people had difficulty with the front end of the

system DOTARS had implemented other means for the submission of applications,

for example hard copy, that ensured that DOTARS staff rather than ACC staff are

responsible for data entry. Ms Riggs

also observed that the 'front end'

is only part of TRAX, and that most of the system supports the internal processing

functions of staff of the department.[110]

Ms Riggs

claimed that the department had made substantial improvements to the system

since July 2003 and that it 'provides

appropriate elements of support'.[111]

2.84

Reports on RP grants which were generated from TRAX and

that were initially submitted to the Committee in January 2005 were wrong in

some important details. Incorrect information was provided to the Committee

about when some applications had been submitted and approved, hampering the

Committee's inquiry. DOTARS had then to

reconcile the data held in TRAX with paper records held in its regional

offices,[112] with the result that the

Committee did not receive reliable data on some important projects until May

2005.

2.85

The Committee is aware that mistakes can be made when people

are entering data into electronic databases and spreadsheets, but it was

particularly unfortunate that in this case those mistakes adversely affected

the conduct of the inquiry. Furthermore, it is not clear what internal quality

control mechanisms are in place to ensure the accuracy of TRAX data in the

future.

Audit and Review

Audit reports and reviews

2.86

In its submission DOTARS listed five external reviews

or audits of three precursor programs—Regional Assistance, Dairy Regional

Assistance and Telecommunications Grants (which included Rural Transaction

Centres) programs—and three internal reviews of the RP and SR programs. Copies

of the executive summaries of those reviews were submitted to the Committee.

The department stated that it had incorporated lessons from those reviews into

the RP program 'to ensure that it operates in line with best practice programme

administration'.[113] This Committee's

report, A funding matter under the Dairy

Regional Assistance Program, June 2003,

was included among the external reviews.

2.87

DOTARS also provided an attachment to its submission

which set out for the RP and SR programs the department's actions to meet the

recommendations of the ANAO's Better

Practice Guide for the Administration of Grants and the recommendations of

the reviews and reports mentioned above.[114]

2.88

As mentioned, DOTARS has conducted three internal

reviews of the RP and SR programs. These reviews were as follows:

-

KPMG (2004), Findings

and Recommendations on the Review of Regional Partnerships Programme;

-

KPMG (2004), Review

of Regional Office Delivery; and

-

KPMG (2004), Review

of the Sustainable Regions Programme Internal Audit.

2.89

The department relied on the first of these reviews for

its assessment that the RP program is delivering substantial benefits to

communities across Australia,

and for a measure of the effectiveness of expenditure under the program. The

department claims that at least $3 is contributed by state government, local

government and the private sector for every program dollar, and that three jobs

are generated for every $50,000, with this rising to four jobs in the longer

term.[115] The review also collected,

among other things, data on the nature of the activities generated by RP

funding and the allocation of funds by type of project.[116]

2.90

DOTARS informed the Committee that its evaluation strategy

for both programs sets up processes to gather performance data on the impact of

the programs against their stated objectives (and outcomes) and that the

strategy is in three stages, as follows:

-

Post-implementation review;

-

Impacts of projects; and

-

External evaluation.[117]

2.91

The first stage of the post-implementation review of

the SR program has been concluded and the second stage commenced. As part of

the first stage evaluation of the RP program, an internal review of a selection

of projects was conducted. The second part of stage one involved a client

survey. That survey had been completed, but the report had not been produced,

by 12 August 2005.[118] The second stage of the RP review is

scheduled for 2006.[119] The external

evaluation of the RP program is to begin in June 2006. The external review of

the SR program is scheduled to report in late 2005-06.[120]

2.92

While DOTARS provided evidence about the macro-level

assessment of the SRP and RPP, the Committee notes that there is little

evidence of evaluation of the outcomes of individual projects—evaluation of

which is fundamental to any measure of the success or otherwise of the

programs. The Committee also notes the absence of a clear link between RP or SR

funding and demonstrated regional development outcomes commensurate with the

quantum of funding.

ANAO Best Practice Guide

2.93

As reported in the previous section, DOTARS submitted

an attachment to its submission (Attachment J) in which the administrative

processes adopted for the RP and SR programs were listed against the principles

set down in the ANAO's Better Practice Guide for the Administration of Grants, May 2002

(the Better Practice Guide). In general, DOTARS has addressed the principles,

but there appear to be shortcomings, which are possibly outside the department's

control. Under 'Grant Announcements'

for example, the ANAO's recommendation is that

grant offers should be made and unsuccessful applicants advised as soon as

possible. DOTARS has asserted that announcements are made as soon as possible,

but the timing of the announcements is a matter for the minister, and DOTARS

may not necessarily know when announcements are made.[121] Additionally, although DOTARS has

produced and promulgated guidelines for applicants in line with the ANAO

principles, there is no mention of the SONA procedures in the guidelines or in

Attachment J to DOTARS' submission.

2.94

The Better Practice Guide also states that the

objectives of a program must be clearly documented and communicated to all

stakeholders, as follows:

Grant programs should operate under clearly defined and

documented operational objectives...Operational objectives for the program should

include quantitative, qualitative and milestone information or be phrased in

such a way that it is clear when these objectives have been achieved, Adequate

information will then be available on which to base future decisions for

continuing or concluding the program.[122]

2.95

However, the RP program has four extremely broad

objectives, which are as follows:

- Strengthening growth and opportunities

- Improving access to services

- Supporting planning

- Assisting in structural adjustment[123]

2.96

The Committee does not accept DOTARS'

claim that these objectives meet the ANAO Better Practice Guide's principle of

defining operational program objectives.[124]

The Committee considers it imperative that the RP program objectives be made

specific to enable the meaningful evaluation of the program.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page