Chapter 4 - Social objectives

4.1

In chapter 1 it was noted that while the Government

placed emphasis on the employment enhancing claims of its policy and

legislation, most of the adverse comment on the policy debate leading up the

introduction of the WorkChoices Bill

concerned 'quality of life' aspects of employment. The claim of 'improved

flexibility' was seen for what it is: an extended period of hours of employment

at a standard wage. There was much discussion on the effects of extended hours

of work on family life, and on likely cuts to special leave benefits.

4.2

This chapter considers the proposed changes discussed

in earlier chapters in relation to social effects, beginning with the likely

effects on female wages and conditions and its implications for sex discrimination

in the workplace. Women constitute the most significant group of workers

experiencing continuing disadvantage in the workforce, particularly in regard

to their ability to balance work and non-work obligations.

4.3

The committee has long noted the indifference of the

Government to Australia's

adherence to international labour obligations. It has presumed that the Government

probably regards International Labour Organisation (ILO) conventions as having

more relevance to advanced first world European countries than to countries

like Australia.

For this reason it is particularly important for this report to relate

industrial agreement changes to ILO benchmarks.

The work and life balance

4.4

Advanced living standards represent the aspiration of

progressive countries. These standards require wages and working conditions

that provide a firm foundation for personal and family development. A floor

under wages and a ceiling over working hours has been a basic principle –

perhaps the central principle – around which industrial relations has been

built for over one hundred years. The principle has become enshrined in the

standard eight hour working day which is the basis of family-friendly work

practices. The contests over pay and conditions have occurred on matters of

detail rather than principle. This is still the case, but long fought-for

rights over hours of work are now threatened by likely employer demands for

'flexibility' in working hours which have the potential to severely

discriminate against people, especially lower-paid workers, in the services and

other industries. Current agreements which might be considered to promote

flexibility and balance in work and non-work obligations are varied and

sometimes onerous, but they commonly include the availability of leave to care

for dependents and flexibility around otherwise regular hours of work. Even

now, the casualisation of the labour force, especially at the low-paid end of

manufacturing and service industries, has no regard for the work and life

balance of individuals and families.

4.5

Press commentary over past months on the issue of work

and life balance has been as illuminating as academic submissions received by

the committee. Economic correspondent Ross

Gittins put the issue of flexibility and

productivity in the perspective of workplace changes when he wrote:

Now, there's no doubt that keeping our factories, offices and

shops open for longer – ideally 24 hours a day – will raise their productivity.

That might not be profitable, of course, if the longer hours were a lot more

expensive in terms of penalty rates.

But get rid of the penalties and the increased productivity will

assuredly lead most of us to higher incomes. ...Trouble is, doing so puts means

ahead of ends. It focuses on the income, forgetting why we want it. It makes us

servants of factories and offices rather than their masters. ...It robs us of our

humanity, taking away our leisure and making us more like robots. The thing

about robots...is that they don't have families and don't need relationships to keep

them satisfied with life.[154]

4.6

The increasing demand for family friendly working

conditions is illustrated by submissions such as from the Independent Education

Union of Australia (IEU), which cited an unmet need for flexibility for

teachers, particularly in senior schools, and the unwillingness by

administrators to embrace flexibility measures. The IEU pointed out that the

option of working part-time is only a partial solution, as for many workers it

is not financially viable, particularly when the part time worker has to pay

for child care. The Union also noted that the teaching

profession is ageing, a fact which brings with it the need for its members to

care for aged or ill parents. Education is hardly alone in this regard. This is

a timely reminder that, while child rearing is perhaps the most common reason

for needing workplace flexibility, it is not the only one.[155]

4.7

Some analysis of 'family friendly' provisions contained

in agreements has been done. At present, according to the Government's figures,

84 per cent of federal certified agreements contain at least one family

friendly measure, and these provisions cover 94 per cent of employees working

under such agreements.[156] On the

other hand, only 70 per cent of AWAs contain any such provisions. The OEA submission

reported that provisions such as these in AWAs are more common among those

working in the private sector, as many public sector employers have made

provision for family-related leave and flexibility through other means.

Employees enjoying these benefits were more likely to come from a large

organisation.[157]

4.8

The OEA submission also said that bereavement leave

(paid or otherwise) was the most common 'family friendly' provision contained

in AWAs surveyed. Given that nearly half of those contained only one such

provision – bereavement leave – for many AWA employees could constitute the

beginning and the end of active provision for a healthy work and life balance.[158]

4.9

The Government's figures are contested by the ACTU, which

claimed that:

Analysis of the evidence upon which the government relies

reveals that it double counts the incidence of provisions that are guaranteed

through awards or legislation, i.e. where a clause [in an agreement] simply

mirrors the provision of an entitlement under an award or in legislation, it is

counted as having enhanced workers ability to reconcile their commitments. This

is ludicrous. When the government's data is examined, only three provisions

appear in agreements in double-digit percentages – carer's leave, part time

work, and single day absences on annual leave. Each of these is standard in

awards, having arisen from the Personal/Carers leave test cases in 1994 and

1995.[159]

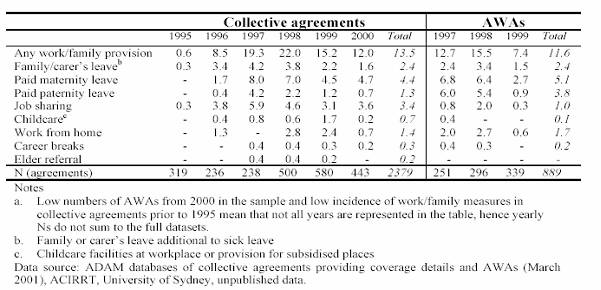

4.10

A study by Dr Gillian

Whitehouse, published in 2001, also

contained findings which were significantly different from the Government's

figures, as is illustrated by the following Table.

Percentage of agreements with reference to work/family measures[160]

4.11

The stark differences in the findings can largely be

attributed to Dr Whitehouse's

omission of provisions which reiterate statutory rights or test case standards.

A number of other disparities are also evident. The research differs from the

OEA findings in concluding that 13.5 per cent of collective agreements and 11.6

per cent of AWAs contained a family friendly measure, and only 7 per cent of

private sector AWAs contained such a measure, compared with 34 per cent in the

public sector.[161] This is in direct

contrast to the OEA's findings, and once again throws doubt on the accuracy of its

statistics.

4.12

Dr Whitehouse

concluded that her data:

... provide little support for optimism about continuing growth in

the use of industrial agreements for work/family provisions ... although the

prevalence of these types of provisions in collective agreements increased

significantly from the mid-1990s, a downturn is evident since 1997/98. A similar trend is evident for

AWAs, with the 1999 figure the lowest of the three years available for all

items.[162]

4.13

Nor does analysis from other sources support the

argument that AWAs are family-friendly. Professor

Bradon Ellem

made the point that women tend to bare the brunt of inflexible workplace

practices and Australian Workplace Agreements are less likely to contain family

friendly provisions:

...[W]e do not find things like flexible working hours ... we do not

find measures to encourage affirmative action within particular workplaces or

to have sexual harassment clauses or child-care facilities. We do not find

those very particular and readily measurable changes taking place in AWAs –

nor, indeed, as I say, in as many enterprise agreements as we might expect or

look for.[163]

4.14

The Queensland Working Women's Service (QWWS) reminded

the committee that the adoption of flexible conditions is often ad-hoc and that

the availability of part-time work was not mandatory for employers of workers

following the birth of a child or after significant changes in caring

responsibilities. The QWWS also submitted that organisational culture was

variable and frequently hostile to the concept of flexibility for workers, and

that the career consequences for women choosing to be away from the workplace

were often significant. Notably, in this context, it also informed the

committee that 'pregnancy discrimination' was reported by 657 of their clients

over a three year period, and that more than half of this cohort was employed

in the clerical or personal services sectors.[164]

4.15

The relative disadvantage of women in terms of their

income and prospects for promotion was set out in a paper by Marian

Baird and Patricia

Todd. The paper argues that the lack of

support for the increasing number of women who choose to combine work with

motherhood is a fundamental example of where workforce measures let women down.

This lack of support includes the lack of universal access to paid maternity

leave. Baird and Todd argue

that the broader use of individual agreements and the reduction in the role of

awards will serve to decrease protections for women who wish to have children.[165]

4.16

Professor Bradon

Ellem also commented on the likely effect of

increased coverage of individual agreements on women, submitting that:

Australia

has very high levels of casual work compared to other OECD countries, which in

turn have negative effects on gender equity and skill development ... the

proposals do nothing substantial to address the work-life balance. In fact, we

argue that the changes are likely to exacerbate the problems of low pay, fewer

entitlements and job insecurity which already affect female employees.[166]

4.17

Notwithstanding the legislative entitlement to parental

leave, the OEA's own data confirmed that less than one quarter of AWAs surveyed

specifically allowed for it.[167]

4.18

Employer groups argued that flexibility benefits both

their membership and workers. The Australian Industry Group (AiG) argued in

support of flexibility in agreement-making, and observed that AWAs fit easily

into a society which values the needs and circumstances of individuals in the

determination of employment conditions. Conversely, awards and collective

agreements were limited in their ability to cope with the differing needs of

individuals.[168] This argument has

also been made by the government in support of increasing the role of AWAs and

'simplifying' the award process.[169]

4.19

However, in her 2001 study of the effect of AWAs on the

work and life balance, Dr Whitehouse

noted that:

... [S]tudies to date of the role of both collective and

individual industrial agreements in delivering work/family measures offer

little encouragement. Agreement databases have shown little incidence of

provisions explicitly oriented to work/family goals and a high incidence of

hours flexibility measures, some of which may impede the successful combination

of work and family responsibilities by reducing control and predictability of

hours.[170]

4.20

The relative failure of collective and individual

agreements to assist in balancing work and private lives was picked up on by a

number of submissions. In addition to the unmet need for flexibility

highlighted by the Independent Education Union[171] the Australian Nursing Federation questioned

the extent to which employers took this issue seriously, observing that while

promises by employers to facilitate the striking of a balance were frequently

made, action was often restricted to a recitation of the human resources policy

manual and little else. This, the Federation submitted, was the underlying

reason for the relative lack of progress.[172]

4.21

The ANF also submitted that their members struggled to cope

with tensions created by work and private demands, exacerbated by labour

shortages in their industry. Indeed, it argued that: 'Nurses often conflicting

roles as family members and community participants appears to be an

increasingly key issue in the way nurses view their employment'.[173]

4.22

The union movement was not alone in levelling criticism

at the wider use of individual agreements. Ms Kate Wandmaker, of the Western

New South Wales Community Legal Centre, stated categorically that, of the

thousands of AWAs she had given advice in relation to, she had never come

across one which provided favourable conditions in relation to being able to

better balance work and family commitments. Ms

Wandmaker observed that AWAs were almost

always drafted by employers, who have been slow in Australia

to realise the benefits of promoting a balanced lifestyle for their employees.[174] In Scandanavia, better family

policies are led by the Government and are then reinforced by companies, not

the other way around.

4.23

It is clear to the committee that neither collective

nor individual agreement-making in Australia

has resulted in sufficient progress in striking a proper balance between work

and non-work activities for many workers. This is a matter of serious concern,

and warrants continued scrutiny in the future. However, the committee finds

that, in all likelihood, AWAs and other individual agreements tend to offer a far

less satisfactory result than do collective agreements for those workers who

have family-related responsibilities outside work. The increased coverage of

AWAs therefore augers badly for the increasing number of employees who require

flexibility in their leave and hours of work. Any government initiative to

reduce the availability of pattern or industry bargaining is likely to have a

negative impact on the ability of employees to strike a balance between their

work and private lives.

4.24

It is worth noting the United

Kingdom, one of the countries the Prime

Minister argues Australia

needs to be more attuned with respect to labour regulation, has recognised the

importance of the work and family balance. The UK Government legislated for six

months government funded paid maternity leave and the right of employees of

children under six (or 18 if the child has a disability) the right to request

flexible hours, including part-time work.

4.25

The committee is also concerned about the negligent

application of the no disadvantage test by the OEA, and the need for inclusion

of leave provisions and negotiations for hours of work ceilings in the list of

allowable matters. It is beyond doubt that a number of unscrupulous employers

will attempt the exploit the 'flexibility' provisions to suit their own

exclusive purposes. With the proposed changes to unfair dismissal laws, lower

paid, and mainly young and female workers will be vulnerable to pressure from

these unscrupulous employers. The committee will be paying particular attention

to this issue when it considers the Government's proposed WorkChoices

Bill.

The gender pay gap

4.26

The fact that women on average in Australia

receive less pay per unit of time is well documented. The Australian Bureau of

Statistics report on Employee Earnings and Hours reported that, as late as May

2004, average income for full-time non-managerial males was $974.90, compared

with $828.00 for women. This represents a disparity of more than 17 per cent.[175] While significant strides have been

made in recent decades, a disparity of this magnitude is of great concern. It

is in this context that the committee has examined the effects of individual

agreements on the gender pay gap.

4.27

The statistics are worrying. It is clear that women

fare better, on average, under registered collective agreements, earning

$678.50 per week in May 2004, than under registered individual ones ($636.60

per week). It is also clear that the difference between average earnings by

males and females in each of the employment categories is greatest in the case

of individual registered agreements. Men working under registered collective

agreements earned on average $943.40 in May 2004, while those on registered individual

agreements earned $1055.20. The latter figure represents an inequity of $418.60

per week, or nearly 40 per cent, between women and men working under similar

employment arrangements.[176]

4.28

The Western Australian Minister for Consumer and

Employment Protection pointed to figures in his own state, where the gender pay

gap is greater than the national average and greater than it was prior to the

introduction of individual agreements in 1993, as evidence of what effect

individual agreements can have on gender pay equality. The Government submitted

that the gender pay gap was up to 9 per cent higher after the introduction of

individual agreements without an award safety net in 1993.[177]

4.29

The committee is not aware of any evidence which

suggests that an increase in the use of individual agreements would help to

close the gender pay gap. Indeed, even under the OEA's own analysis of the ABS

data, women are considerably less well off under AWAs than under awards or

collective agreements. The OEA submission said that women employed under AWAs

are worse off in both the private and public sectors:

Overall, the data shows that AWA females earned approximately 60

per cent of their male counterparts' earnings. The overall [certified

agreement] and Award female earnings ratio was higher, at 69 and 79 per cent

respectively.[178]

4.30

The Textile, Clothing and Footwear Union of Australia

provided the committee with an example of where women working under a certified

collective agreement had been 'organised' into a lower level classification

than their male counterparts. The certified agreement provided for an

independent review of the classification structure by the AIRC, enabling the

situation to be challenged. The Union points out that, under individual

agreements, there would be no guarantee of pay equity in the first instance, let

alone scope to mount a challenge to any unfair gender imbalance.[179]

4.31

The statistics and other evidence leave little room for

doubt. It is clear that, on average, women fare worse under individual

arrangements than under centralised or collective ones. The simple application

of logic supports the conclusion that broader use of AWAs in the workplace will

bring about a widening in the gender pay gap, and that women stand to lose from

such a development.

4.32

The Committee is also concerned that in some states,

such as Queensland and New

South Wales, the state industrial relations

commission have developed equal remuneration principles which have been used as

a key mechanism to run pay equity cases to remedy the undervaluation of work

undertaken primarily by women. Such a mechanism does not exist at the federal

level, and with the Commonwealth Government planning to take over the state

system, there will be little opportunity to achieve pay equity.

International obligations

4.33

The ACTU submitted that the current bargaining

arrangements breach Australia's

international obligations under International Labour Organisation Conventions

87 and 98. The Council submitted that the Workplace Relations Act, as well as

sections of the Trade Practices and Crimes Acts, had been singled out for

adverse comment by the ILO in relation to Convention 98, particularly insofar

as they neglect to promote collective bargaining, restrict the subject matter

of agreements, and favour workplace bargaining over bargaining in other forms.

The Council also argues that Convention 87 has been contravened through

provisions in the Act which restrict strike action.[180]

4.34

The Committee majority acknowledges the analysis put

forward by the ACTU in relation to Australia's

likely breach of ILO conventions. However, due to the scarcity of evidence from

other sources in relation to this matter, the committee majority is unable to

comment further.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next page