Chapter 1 - The evolution of workplace agreements

1.1

This is an introductory chapter which describes and

outlines themes and arguments that will be presented more fully in the

following three chapters. It puts the current interest in workplace agreements

in an historical context, recognising that the pace of change has quickened

suddenly in the light of the imminent introduction of the WorkChoices

Bill. As was explained in the Preface, it

has not been possible in this report to avoid anticipating what is likely to

come with the WorkChoices Bill.

1.2

There is considerable commentary on the evolving

process of wage determination over the past dozen years. Most areas of

employment have been affected. Movement away from centralised wage fixing began

with amendments to the Industrial Relations Act in 1993, toward enterprise

bargaining arrangements, a move by the Keating Government which was initially

opposed by sections of the union movement.

1.3

Since then, a diminishing proportion of the workforce

has directly relied on industry-wide awards, which provide a comprehensive set

of wages and conditions per industry, and which provide the current safety net

for lower-paid members of the workforce. These are generally unskilled workers

but also cover part-time and casual workers and immigrant skilled workers with

poor English. Very large numbers of employees indirectly rely on awards, using

them as the base starting point for collective and individual agreements, or,

with respect to specific provisions, as default provisions. Skilled workers,

and certainly those represented by unions, generally enjoy above-award wages

and other benefits of enterprise agreements. However, it remains the case that

the award system continues to underpin the wages and conditions of workers who

have collectively and individually negotiated above-award wages; and acts as an

important safety net for the remaining workforce. Such wage differentials in

the workforce are not exceptional, as they were fifteen years ago, and are a

notable characteristic of the current wages structure.

1.4

The central issue in the debate over industrial

agreements, which is the subject of this report, is the extent to which the

current trend toward wider disparities in wages and conditions can continue.

Traditionally, the award structure has put a substantial floor under wages.

This report deals in part with the consequences of the removal over time of the

award structure, and its replacement by new mechanisms and agreement processes

which many claim will widen the wages gap and create a permanent underclass of

unskilled employees existing barely above poverty levels. There has been much

speculation on the social consequences of such a development. It is feared it

will move Australia

towards the harsher and less egalitarian USA

practice. The spectre of poverty and social alienation that is evident on the

extensive fringes of American society concentrates the minds of many

commentators, who also acknowledge that in many other respects the conditions

and traditions of governance which prevail in the United

States find no mirror in this country.

1.5

Of relevance to this inquiry are the social

consequences of New Zealand's

experience with individual contracts during the 1990s. It has been widely

reported that the Employment Contracts Act of 1991 had disastrous consequences

for workers who had previously relied on industrial awards to provide a safety

net of minimum wages and conditions. The new system of individual contracts

introduced in 1991 was a disaster for jobs, wages and productivity, resulting

in a significant rise in the number of 'working poor'.[1]

1.6

The other side of this argument draws heavily from the

necessity of continuing with the work begun with the 1993 legislation ushering

in enterprise agreements, based largely on the assumption that economic

imperatives make further movement along this path essential. That is, reform

must follow reform in a continuing cycle in the direction of sustaining maximum

productivity. To stand still is to go backwards. Proponents of this line of

argument emphasise its importance at a time when the economy of the country is

subject to unrelenting global competition.

Historical context

1.7

In the last 20 years, Australian wage fixation has

moved incrementally from a centralised model of awarding national wage increases

to match increases in the cost of living, to a much more devolved system, where

wages are primarily set at the workplace level, often based on improvements in

productivity.

1.8

This shift first started to occur in 1987, with the

Commission's introduction of the Restructuring and Efficiency Principle.[2] This was reinforced (albeit at an

industry level) by the Structural Efficiency Principle[3] which accelerated following the

development of the Enterprise Bargaining Principle in 1991.[4]

1.9

From this time, the Commission's decisions and the

Government's legislative action (most significantly through the Industrial Relations Reform Act 1993 and

the Workplace Relations and Other

Legislation Amendment Act 1996) have facilitated this shift in focus from

national and industry level wage fixation to workplace level wage fixation. In

broad terms, by the mid 1990s, there was general acceptance of the principle

that industrial agreements could not be fairly made without regard for the

profitability – and the capacity to pay higher wages – of businesses,

especially in such a diverse economy when not all businesses were profitable at

the same time.

The Workplace Relations Act and

subsequent amendments

1.10

Following the Coalition's election in March 1996, the

Government introduced the Workplace

Relations and Other Legislation Amendment Act 1996, which renamed and

significantly reformed the Industrial

Relations Act 1988. The amendments focused on achieving wage increases

linked to productivity at the workplace level. The new name of the act

reflected this, as did new provisions relating to negotiating and certifying

agreements. The act also introduced a new form of agreement, Australian

Workplace Agreements (AWAs), which could be made between an employer and an

individual employee.

1.11

Two other significant changes were to restrict the

Commission's ability to make awards in relation to matters outside a core of 20

'allowable award matters' set out in section 89A, and the introduction of

provisions requiring the Commission to review and simplify awards to remove all

provisions falling outside these 'allowable award matters' after a transitional

period of 18 months. These provisions achieved what the Commission had decided

it could not do itself under the former legislation; this is, limit the content

of the award safety net to a set of core minimum conditions.[5]

1.12

The simplification of Federal Awards to 20 allowable

matters had the most significant effect of removing restrictions on casual

labour. Although the rise of casual labour from 18.2 per cent of the workforce

in 1988 to 26.6 per cent of the workforce in 2004 is a significant trend, its

effect on workers has been more recently felt.[6]

The committee believes it is a trend which will continue under proposals

contained in the WorkChoices Bill.

1.13

The role of the Commission, and that of its awards, has

developed to reflect the increasing emphasis on setting wages and conditions by

agreement at the workplace. It was inevitable that the scope for arbitration by

the Commission would be reduced in line with these changes, and the Commission

itself had recognised this earlier.[7]

1.14

It is worth noting that the Government did not get

their full proposal through the Senate. In the end, there were 176 Democrat

amendments made to the original legislation.

1.15

Having been successful in having the Workplace

Relations Act passed, with substantial amendments insisted on by the Senate,

the Government thereafter had less success with subsequent amendments to the

act. Many of the amendments the government has sought to make to the act in the

years since 1996 have been thwarted by the Opposition and other parties in the

Senate. While that is true, the extent of Government failure should not be

exaggerated. It is common for the Government to claim that their legislative IR

agenda has been routinely obstructed in the Senate, but up until June 30 2005 the Coalition secured

passage of 18 workplace relations bills through the Senate. Of these, five were

supported by all parties and passed without amendment, including the very

substantial Workplace relations (Registration and Accountability of

Organisations) Bill 2002.

1.16

The first significant amendments proposed after 1996 were

contained in a major bill, the Workplace Relations Legislation Amendment (More

Jobs, Better Pay) Bill 1999. The bill, often

referred to as the MOJO Bill, sought among other things, to reduce the role of

industrial awards, reform the certification of agreements and the making and

approval of AWAs and to clarify rights and responsibilities relating to

industrial action. It also sought to reduce allowable award matters, restrict

union right of entry provisions and review provisions for freedom of

association. This bill lapsed at the end of the 39th Parliament. Following

the failure of MOJO to pass the Senate, this comprehensive amendment bill was

'unpackaged' into separate constituent bills which were reintroduced in

following years. A number of less contentious bills were passed.

1.17

One of these was the Workplace

Relations Amendment (Genuine Bargaining) Act 2002, which specified

factors to be taken into account by the Commission when considering whether a

negotiating party was genuinely trying to reach agreement, and which empowered

the Commission to make orders in relation to new bargaining periods.

1.18

The Workplace

Relations Amendment (Better Bargaining) Bill 2003 proposed to

restrict access to industrial action before the expiration of an agreement,

provide more ready access by employers to cooling-off periods, allow third

party suspensions of industrial action and limit union access to protected and

unprotected industrial action. The bill lapsed at the end of the 40th

Parliament.

1.19

Most recently, the Workplace

Relations Amendment (Simplifying Agreement-making) Bill 2004 sought

to simplify certified agreement-making at the workplace level, reduce the

delays, formality and cost involved in having an agreement certified, and

prevent interference by third parties in agreement-making. It also sought to

provide for the extended operation of certified agreements of up to five years.

The bill lapsed at the end of the 40th Parliament.

1.20

The brief chronology above pertains primarily to

amendments in relation to widening the scope of agreement-making. With its

newly realised Senate majority, the Government has announced its intention to

introduce legislation into the Parliament in late 2005 in its latest attempt to

'simplify' agreements. Announcements from the Government suggest that the bill

will seek to encourage the use of Australian Workplace Agreements (AWAs) at the

expense of collective agreements, and dismantle the award structure over time.

The Australian Industrial Relations Commission (AIRC) will have responsibility

for simplifying awards, regulating industrial action and registered

organisations, and will play a role in relation to termination of employment.

Employers and employees will also be able to use the AIRC to help them resolve

a dispute. The new Australian Fair Pay Commission will set and adjust a single minimum

wage and determine other working conditions within a framework of a reduced

number of allowable matters. These are expected to include annual leave, carer's

leave, parental leave, and maximum ordinary hours of work.

Agreements: their scope and coverage

1.21

This section provides a descriptive summary of the

nature and coverage of enterprise and individual agreements in the context of

the broader employment framework, since the passage in 1996 of the Workplace Relations

Act.

1.22

The act introduced significant changes to the

legislative framework of formalised agreement-making in the federal

jurisdiction. Under the act, there are a number of options for making an

agreement, both formal and informal. Formal options include a certified

agreement (CA), which are most commonly certified by the AIRC under either

section 170LJ (employer and employee organisation), or section 170LK (employer

and a majority of employees). Other options exist for the formation of a CA

pertaining to new businesses and for the settlement of industrial disputes.

1.23

The other type of formal agreement is AWAs, which were

the first non-collective agreement to be recognised by legislation in the federal

jurisdiction. AWAs are made directly between an employer and an employee, and

are approved by the Employment Advocate.[8]

1.24

The Australian Bureau of Statistics collects and

publishes data relating to the scope and coverage of different agreements, as

well as incomes. Registered agreements are statutory instruments and

unregistered agreements are common-law agreements. The ABS records the most

common methods of setting pay for all employees in May 2004 as being registered

collective agreements (38.3 per cent), unregistered individual arrangements

(31.2 per cent) and award only (20.0 per cent). Unregistered collective

agreements (2.6 per cent) and registered individual agreements (2.4 per cent)

were the least common methods of setting pay. The remaining 5.4 per cent of employees

were working proprietors of incorporated businesses.

1.25

The most common methods of setting pay for full-time

employees were collective agreements (41.5 per cent) and registered and

unregistered individual arrangements (38.9 per cent). For part-time employees, collective

agreement (39.7 per cent) and award only (34.3 per cent) were the most common

methods of setting pay.

1.26

The median weekly total earnings for full-time adult

non-managerial employees who had their pay set by awards only were $625.00.

This compares with median weekly total earnings of $904.00 for full-time adult

non-managerial employees who had their pay set by collective agreements and

median weekly total earnings of $814.00 for full-time adult non-managerial

employees who had their pay set by registered and unregistered individual

arrangements.[9] The committee notes that

ABS figures do not differentiate between those agreements, collective or

otherwise, which are in part underpinned by award provisions.

1.27

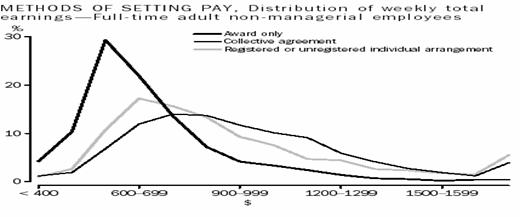

The following graphic illustrates the use of different

employment arrangements across the income levels.[10]

1.28

The committee does not know how many AWAs are currently

operative. Data relating to AWAs, and to an even larger extent non-AWA

individual agreements, can best be described as estimates. They are individual

agreements and confidential documents, running for differing lengths of time. At

the committee's hearing in Perth, Western Australian Minister, Hon John Kobelke

MLA, also referred to the difficulty in obtaining accurate data on the coverage

of workplace agreements.[11]

1.29

The Office of the Employment Advocate (OEA) has submitted

that AWA approvals have enjoyed an annual growth rate of 29 per cent over the

past three years, and an even higher rate for small to medium businesses. The

OEA also estimated that 'industry penetration' by AWAs stands at 5.4 per cent nationally.[12]

1.30

Professor David

Peetz has taken issue with the OEA's

submission, arguing that:

...[I]t is important not to misinterpret cumulative OEA lodgement

data as providing any measurement of actual coverage, as there is substantial

potential for double and triple counting of AWA employees who leave and are

replaced by AWA employees or who sign replacement AWAs ... The OEA estimate that

5.4 per cent of the Australian population was 'covered' by AWAs in June 2005 is

implausible, given that only 2.4 per cent were covered in May 2004, only 217

000 AWAs (equivalent to about 2.7 per cent of employees) were approved in

2004-05, and many of the workers covered by AWAs in May 2004 ... would have

either left their jobs or been covered by replacement AWAs.[13]

1.31

The ACTU had similar concerns, pointing to a disparity

in the number of AWAs estimated to be in force by the OEA and the ABS of more

than 226 000. This equates to a disparity of 115 per cent.

1.32

Professor Peetz

also pointed to ABS data which makes clear that growth in the number of

employees covered by collective agreements from 2002 to 2004 far exceeded the

likely rise in registered individual contracts.[14]

1.33

One of the main criticisms of the use of the ABS data

to support the view that the coverage of individual agreements is growing

rapidly relates to the way the ABS categorises employees. Professor

Ellem argued:

[T]he way that the Australian Bureau of Statistics count these

figures is not the most helpful way of doing it. When they do their samples,

any one employee is classified into only one category whereas ... a large number

of or most employees in effect have their wages and condition determined by a

combination of instruments. For example, if your wages and conditions are

determined by a federal award and some kind of individual agreement then

modifies some part of that agreement ... [the ABS] would count such a person as

being in the individual agreement-making category only. [Thus] we do not really

know for sure what the make-up of the regulation of the Australian labour

market is at the moment in any sophisticated way.[15]

1.34

Professor Ellem

continued:

I am saying that it is a genuinely difficult problem and there

are legitimate ways of going about it. All that we want to do is to make sure

that we are comparing like with like.[16]

1.35

Professor Ellem's

observations appear to the committee to be well founded. The glossary of the

relevant ABS report discloses that those in the individual arrangement category

include employees who had the main part of their pay set by an individual

contract, registered individual agreement, common-law contract, or an agreement

to receive over-award payments.[17]

1.36

Finally, it was pointed out that figures from Western

Australia are skewed as a result of a change of government.

There is a higher proportion of AWAs in effect in Western

Australia than in any other state. This is partly due

to the prevalence of AWAs in the mining industry, but also because most of the

workers formerly covered by Individual Workplace Agreements went over to AWAs.[18] Nonetheless, it is clear to the

committee that the scope and coverage of AWAs across the country is open to considerable

dispute.

What do AWAs cover?

1.37

The most comprehensive analysis of AWA content was

carried out by the Australian Centre for Industrial Relations Research and

Training (ACIRRT) based on sample AWAs provided by the OEA between 2002-03. Issues

commonly dealt with in AWAs include wages and other remuneration, span and

flexibility of hours, leave provisions, and so-called 'family friendly'

provisions. Of these, the most commonly covered issue is span and flexibility

of hours, which 82 per cent of surveyed AWAs made reference to. Only 15 per

cent of AWAs placed a limit on the number of hours to be worked in any one day,

with 4 per cent of agreements allowing for more than 12 hours per day to be worked.[19]

1.38

Professor Peetz's

submission contended that the span of hours is the predominant issue covered by

AWAs, and he draws on ACIRRT research to argue that AWAs tend to provide for annualised

working hours which are longer than other agreements. These 'annualised hours' can

leave workers at a significant disadvantage because they tend to be paid at

ordinary-time, rather than overtime rates of pay.[20] This results in wages being devalued

over time. This was the general experience in Western

Australia under its previous system of individual

workplace agreements (IWAs). The Western Australian Government submission noted

that while many IWAs included very open-ended hours of work under the guise of

flexibility: '...an analysis of the loaded rates of pay for these workers did not

appear to make up for the increasingly open and flexible hours of work

arrangements'.[21]

1.39

The committee heard evidence from Ms

Janine Freeman,

Assistant Secretary, UnionsWA, that inclusion of annualised working hours in

AWAs raises serious health and safety issues. Ms

Freeman described the effect of annualised

salaries on the ambulance officers who worked at Port Hedland:

They had workplace agreements to annualise their salaries. At

first the salaries looked extremely attractive because they were annualised and

took things into account...When they looked at the hours they were working, the

amount of call-out they had to do and the additional duties that were

considered in the workplace agreement, they found that, if they had been on a

certified agreement, they would have been underpaid. The impact on families in

Port Hedland – in remote and regional areas – was quite harsh and caused a lot

of difficulty.[22]

1.40

The next most common employment condition covered by

AWAs is leave, which was specified in 74 per cent of agreements, followed by

'family friendly' provisions such as parental leave or additional flexibility

when required for family-related contingencies.

1.41

Alarmingly, only 38 per cent of AWAs covered by the

survey made reference to wage rises, and in 41 per cent of AWAs one or more

loadings such as overtime had been 'absorbed' into an overall rate of pay.

1.42

The ACTU drew on data from the Department of Employment

and Workplace Relations (DEWR) to show that even collective agreements are

frequently left wanting in content detail. Only about 29 per cent of employees

covered by certified (collective) agreements are covered by comprehensive agreements.

Comprehensive certified agreements appear most frequently in the construction,

manufacturing, retail trade, and transport and storage industries. However,

with the exception of retail trade, these agreements account for only a small

proportion of employees covered by this type of agreement.[23]

1.43

Hence, for the purpose of this report the committee

assumes that the number of AWAs currently in effect is uncertain, but that

awards and collective agreements still set wages and conditions for the

majority of the workforce.

Characteristics of employment under

AWAs and other individual agreements

1.44

There is a significant proportion of the workforce which

relies solely on awards and informal agreements. Workers operating under

awards, and forms of unregistered agreements, total one quarter of the

workforce, and are primarily those on lower incomes. They include a high

proportion of women, and young and casual workers. As the ACTU argued:

While there has been rapid growth in the number of employees

covered by formal bargaining, awards remain relevant in setting the wages of

one in five employees ... [A]wards [also] remain relevant in underpinning

bargaining for the majority of employees employed under collective agreements.[24]

1.45

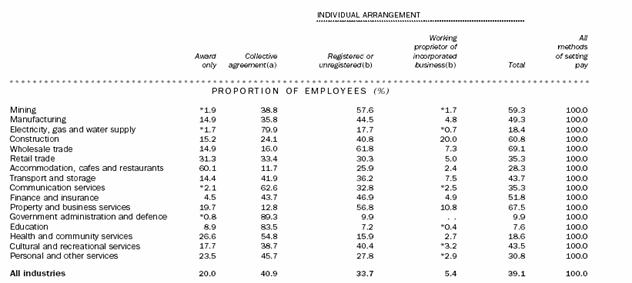

The

following table illustrates the coverage of individual agreements among

different industry groups.[25]

1.46

The table shows the preponderance of workers employed

under individual agreements who are occupied in the mining, wholesale trade,

finance, manufacturing, property and business sectors. There is evidence to

suggest that a significant proportion of these workers are not party to an AWA,

but rather are engaged in informal over-award common-law agreements.

1.47

What is also clear from the table is the situation of workers

in the burgeoning hospitality (hotel, cafes and restaurants) sector, who are

more often than not working solely on awards, while those in retail, health and

community and personal services also have a high rate of award adherence. These

industries are among the highest employers of casual and female workers, as

well as being among the lowest paid, particularly for women.[26] Any move toward AWAs which is

facilitated under forthcoming legislation will probably affect these employees as

the award structure gradually winds up.

1.48

It is pertinent to note here that in promoting

individual agreements, employers are resisting collectivism and promoting

workplace flexibility, but on their terms only. As the committee heard from one

authority:

The two biggest changes that have taken place, including in the

services sector but more broadly in manufacturing, are an increase in the

number of employees on 12-hour shifts. There is also an increase in the basic

length of the working day to 12 hours. That does not mean necessarily that

people work 12 hours a day but it means that any time within the 12 hours is

considered ordinary working time. It reduces payments for working unsociable

hours. ...I think that in those sectors in particular the really critical thing

about AWAs compared to any kind of old collective agreement is that what it is

really about is individualising the process of making the agreement itself. It

is about individualising employee representation at work and, I think, in

effect reducing real flexibility for employees and reducing their voice in

relation to their employer when they have a grievance or a concern.[27]

1.49

Evidence such as this puts a basis of academic research

beneath instinctive distrust of workplace arrangements which avoid the scrutiny

imposed by traditional processes of collective bargaining and tribunal

decisions. This is the basis for fears that AWAs will not promote socially or

family-friendly working conditions. Wage justice may be achieved through AWAs,

as experience with mining and high-skill jobs has demonstrated, but even in these

cases the costs to individuals has been high, and is barely sustainable over a

working career.

Pattern bargaining and pattern agreements

1.50

Few industrial relations practices infuriate the

Government more than 'pattern bargaining', whereby union managements across a

state attempt to negotiate an identical enterprise agreement across comparable

industries within a state. The Government claims that this defeats the

rationale for enterprise based agreements based on shared interests of a firm

and its employees. It argues that a firm's level of remuneration should be

based on its capacity to pay, and its capacity to trade productivity increases

with higher wages.

1.51

Peak employer bodies dutifully condemn pattern

bargaining, but evidence to this committee's inquiries over a number of years

from peak body constituents appears to be ambivalent. As wages make up the bulk

of expenditure outlays, any practice which sets predictable wages at the same

level across an industry greatly simplifies cost estimates for firms tendering

for work. Pattern bargaining, especially in the building and construction

industry, saves a great deal of management time and allows contractors to

remain competitive on the basis of work practices, contract management and in

managing the cost of materials. Productivity gains are no less assured under

these conditions than in having to bargain large numbers of individual

agreements.[28]

1.52

The Government's stand against pattern bargaining for

collective agreements in the private sector is in contrast to its own habit of

pattern bargaining for collective agreements in the public sector. Its stand

against pattern bargaining for collective agreements in the private sector is also

juxtaposed to its support of pattern individual agreements in both the private and

public sectors. Anyway, AWAs are mostly not 'bargained' agreements but are

imposed agreements, the only likely exceptions being those for very high income

employees. Nor do AWAs extend across an industry, although the variations may

be slight in areas with skill shortages.

1.53

Some evidence suggests that many employers prefer

awards and statutory collective agreements. They provide a base upon which to

build common-law agreements. They provide a standard of wages and conditions

which is useful. Professor Bradon

Ellem agrees, arguing that, for many

employers, transparent, efficient and equitable occupational health and safety

and workers' compensation schemes are more important.

Conclusion

1.54

The argument about industrial agreement-making is about

the relativities of bargaining power. The Government has taken the view that

the upper hand in bargaining for wages and conditions has generally been held

by employees, backed by their unions and the apparatus of wage-fixing

institutions. Hence the frequent claim of its legislative intentions as

securing 'balance', 'choice' and 'flexibility'. There is an unspoken assumption

in Government circles, and some employer circles, that in many areas of

employment wages are too high. Yet the Government also claims as a justification

for AWAs that wages will increase. Evidence suggests that they will, but only

in highly professional and highly skilled jobs, and in the particular

circumstances of some industries, and as a result of volatility in the labour

market and the long-term trend toward labour shortages in certain sectors.

1.55

The Government's legislative intent since 1996, which

continue with the imminent WorkChoices

Bill, has been to tilt bargaining power toward

employers. It is a policy based on dubious assumptions about the relationship

between employers and employees. The policy rationale is as follows: the

economic is more important than the social; a philosophical objection to

collective agreements (including awards); and an assumption that employment

relations should regulate employees as economic units, who exist primarily for

work. As a corollary to this, employers stand in a naturally ascendant

relationship with employees, and their needs are therefore paramount. The

system of individual contracts proposed by the Government will significantly

enhance managerial prerogatives and diminish the independence and choice

available to employees.

1.56

The reason given for the paramount importance of

employer demands is the need to increase productivity. The flaw in this

argument is that labour costs and hours worked are only two elements in the

productivity equation. It will be argued in chapter 3 that squeezing labour is

far less effective in raising productivity than improved management, technology

and the injection of capital. What evidence we have shows that productivity in

general is highest in firms in which collective, rather than individual,

agreements are the norm, and where the security, and therefore contentment, of

employees is manifested through good work performance.

1.57

As will also be noted, it is not productivity that

concerns businesses as much as profitability. It is true that cutting labour

costs may increase profits in some circumstances, but this can be a blunt

instrument in dealing with market cycles. If labour costs are significantly

reduced, the flow-on effect through the economy will affect consumer demand. As

employer's profit share is already at a record high of 27 per cent of GDP, and

workers' wages share is almost at the lowest on record at 53 per cent of GDP,

this committee agrees with commentators who wonder what the real purpose of

these changes is.[29]

1.58

Perhaps the answer to this question was given by one of

the key witnesses to this inquiry, who reminded the committee, that the focus

of workplace changes proposed now and in the past by the Government is less

concerned with outcomes than with process.[30]

As the committee has observed before in dealing with numerous amendments to the

Workplace Relations Act, the micro-regulation of industrial legislation ensures

that process has become an end in itself; that hoops must be jumped through in

particular order, lest employers be tempted to take a pragmatic view of the

responsibility they have to hold the line with the Government in whatever it is

attempting to achieve.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next page