CHAPTER 1

Grasping the issues

1.1 Regional Australia has been the focus of greatly increased attention

in recent years: a recognition of the relative decline of rural and regional

economies and communities. The then Industry Commission undertook a study

of regional industry in 1993. [1] Two reports published in 1994 have become widely

quoted: one by McKinsey and Company, commissioned by the former Department

of Housing and Regional Development, and another by the (Kelty-Fox) Regional

Development Taskforce. [2] There is an increasing volume of academic research

and writing on the condition of regions which the Committee has gratefully

called upon to inform its views and recommendations.

1.2 In the first term of the Coalition government, elected in 1996, official

interest in regional matters appeared to wane as relevant agencies were

disbanded, resulting in the loss of 220 public service positions and some

$150 million in program funding. The government did, however, retain the

regional structure of Area Consultative Committees (currently 58 of them)

and moved to change the focus of their activities. More recently, the

attention of government has returned to regional matters, as reflected

in the title of the newly expanded Department of Transport and Regional

Services.

1.3 The Committee notes the government's announcement of its regional

policy made on 11 May 1999, and contained in the statement Regional

Australia: Meeting the Challenges. While some members of the Committee

regret the limited scope of regional policy action which characterises

the statement, all members commend the government for acknowledging, through

its proposed Regional Australia Summit, and regional forums, the need

to involve regional interests in the direction of future policy. The Committee

sees this as an encouraging move toward redirecting policy making from

an exclusively Government process to a broader more consultative process.

1.4 A difficulty arises in estimating the effectiveness of a regional

development strategy aimed at fostering new growth concepts in regional

areas. The Committee believes that in general, governments have not fully

focused upon the necessary requirements to enduring prospects in regional

areas. The issue has not been a lack of acceptance of the need for regional

development policy but rather a lack of a consistent approach that transcends

the political cycle, and one that is coherent between all levels of government.

1.5 Governments also increasingly expect the private sector to assume

the risks in any development. Currently the status quo is that joint ventures

are to be encouraged provided that governments are not required to bear

excessive risks. This raises the question of the role of government in

regional development. It can be argued that the private sector is likely

to be more risk averse than governments as there is a requirement to achieve

an adequate return for their shareholders. Therefore in many cases it

may be necessary for governments to `kickstart' the process. The value

of this report, the Committee hopes, will be in addressing some of the

political realities and imperatives involved in regional policy making.

1.6 These are complex issues. There are some claims that financial assistance

remedies are more likely to distort the overall balance of economic growth

than to benefit depressed regions in the long term. Policies directed

at more focused and sustainable regional development planning are claimed

to be difficult to formulate and execute with the overlapping responsibilities

of three spheres of government. [3] The Committee

is aware, nonetheless, of a residual sympathy in Australia for the `bush

battlers', though this may be coming to an end as new generations of city

dwellers lose their contacts with rural Australia. It is also aware that

the viability of rural and regional industries has been subject to rigorous

and continuing evaluation by government agencies, banks, investors and

environmentalists.

1.7 Above all, the Committee is aware that while only a minority of people

live outside the metropolitan areas, the issues of `city versus the bush'

have a social and economic dimension that economic rationalism can find

no answer to. The Committee understands that global forces and economic

policy changes over the past fifteen years have provoked a degree of dissatisfaction

in some regions, and increased perceptions of relative deprivation and

government neglect. Regional employment remains, therefore, an issue of

continuing political importance. The Committee's view is that despite

currently fashionable opinions favouring a minimalist role for government

on issues of progress and development, governments can not declare a `policy-free

zone' in relation to regional affairs.

1.8 An inquiry into employment and unemployment necessarily involves

a close look at the evolution of regional economies. The mantra `jobs,

jobs, jobs' unfortunately conceals the reality that employment is a consequence

of investment in marketable goods and services. No matter how efficient

and committed employment agencies may be, they cannot create jobs. Nor

are job creation projects effective unless they connect beneficiaries,

eventually, with unsubsidised employment in viable industries. Employment

is an investment in human capital; but one dependent on market return.

It is a harsh economic fact that investment in the production of goods

and services either no longer requires a large component of human capital

or requires skills which a large number of people do not possess. Up-skilling

of the Australian workforce, particularly in regional areas, clearly presents

a major challenge which governments can not ignore.

1.9 As this report notes at several points, the forces of economic change,

particularly to trading and investment patterns and decisions may well

be matters largely beyond the control of governments. This does not absolve

governments from exercising their responsibilities to deal with the impact

of these forces on the Australian economy. Governments must engage in

some serious policy planning to ensure that the development of Australia's

competitive advantage includes programs for re-skilling the regions, developing

their infrastructure, growing sustainable industries and encouraging the

flow of investment to them.

1.10 McKinsey and Company (1994) found that the success of regional economic

development depends to a large extent on the commitment, quality and energy

of business and community leadership. [4] In

submissions and oral evidence received by the Committee, the importance

of approaching regional development from the bottom up was also stressed.

The Committee believes that the Commonwealth must play a key role in the

facilitation of regional development strategies which are based on the

initiatives generated in the local areas themselves and in the coordination

of the actions of state and local governments and their respective agencies.

Regional disparities in employment

1.11 In a dynamic world economy it is to be expected that not all regions

would maintain their position in the prosperity league. Globalisation

and structural economic change affect regions in different ways. Many

of Australia's regions are growing rapidly and are taking full advantage

of growing trade opportunities, thereby attracting national and international

investment across industries as diverse as tourism, dairy farming, mining

and viticulture. [5] Other regions are less

fortunate. Disparities in employment in regional Australia are starkly

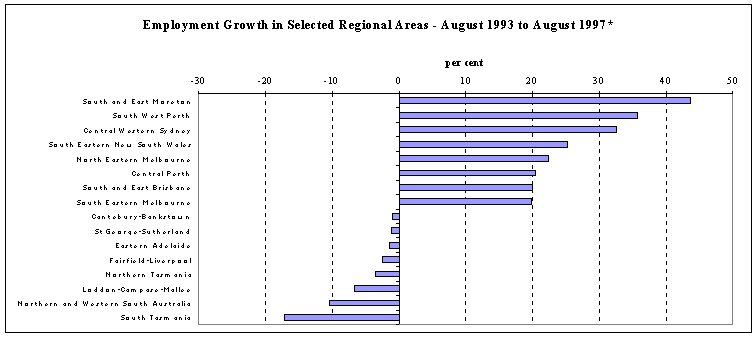

evident in the following charts:

Source: Submission no. 166, Department of Employment, Education, Training

and Youth Affairs, vol. 8, p. 100

Source: DEWRSB, Australian Regional Labour Markets, No. 86

1.12 The worrying aspect of regional disparity in Australia is the experience

of inexorable decline in some centres of population. For many regions

there is unlikely to be any upward curve on the economic cycle to look

forward to. Location, resources and markets are the determinants of survival.

Thus, regional centres like Broken Hill, Port Pirie and Whyalla will almost

certainly continue to decline, not only because of global considerations

but because local sources of raw materials will soon be exhausted. Tasmania's

primary industries have been affected by changes to world trade patterns

in the past and more recently to global pressures on manufacturing and

process industries. Its remaining specialised and high valued trade commodities

are not produced by labour intensive industries. Outer metropolitan areas

of the major cities continue to show the unemployment effects of shifts

in investment toward industries and services where human capital needs

are determined by levels of skill rather than by weight of numbers.

1.13 Technological change is an important determinant in influencing

regional disparities. For instance the telecommunications revolution will

bring employment opportunities. [6] Regional

centres like Launceston and Ballarat welcome the advent of telephone call

centres as large–scale employers. Other regions believe they see

few of the advantages of the telecommunication revolution. The antagonism

of people in more remote areas of Australia to the sale of Telstra is

significant because of assumptions made that access to the most sophisticated

telecommunications system available is essential in maintaining global

competitiveness for remotely centred businesses.

1.14 In South Australia, a factor identified as a cause of regional disparity

in employment has been a regions' proximity to the metropolitan area.

The closer a region is to the city, the more advantages business in those

areas receive through lower transport and other transaction costs, including

availability of infrastructure and a potentially large labour market.

[7]

1.15 This experience in one state has more general application according

to the submission to this inquiry from the former Department of Employment,

Education, Training and Youth Affairs (DEETYA), which stated, among other

observations, that people in smaller populated regions often had to accept

jobs for which they were over-qualified; or remained unemployed for longer

periods. Industries in metropolitan areas were able to react faster to

cyclical changes in the economy, achieve faster rates of growth during

upswings, and did not experience skills shortages like non metropolitan

industries, as they were able to access a much larger labour market. [8]

1.16 Another factor influencing regional disparities in employment is

labour mobility. Displaced workers are most often unable to move to areas

where their skills may be in demand because of financial and family constraints.

Home ownership is a powerful disincentive to move when house prices are

depressed in towns and cities in decline. This is especially the case

with older workers, for whom `quality of life' is an associated reason

for lack of mobility where location is seen as ultimately the most important

consideration in a life which may extend twenty years beyond retirement.

It is the next generation, without ties, which moves out, affecting the

demographic profile of regional centres. As Professor Rolf Gerritsen told

the Committee:

What is happening in these towns is that young people – and that

is fairly common throughout rural Australia – with any talent finish

school and leave. Entrepreneurs with any talent move out. The entrepreneurs

who remain in these sorts of towns are risk averse; they are basically

running down their capital. There is substantial asset deflation in

these areas which operates independently of the Australian economy and

is another feature of this `terminal decline'. So we have a situation

where these communities are in very severe economic straits. They have

extremely high crime rates which are associated with poverty and unemployment.

[9]

1.17 Professor Gerritsen commented that there was a migration back to

these communities of people who did not succeed elsewhere. Reverse migration

was a characteristic of towns like Walgett and Bourke, particularly for

Aboriginal people.

1.18 Another factor entrenching economic stagnation in many regions is

a shortage of skills in a region. A number of witnesses referred to the

lack of general education and low retention rates in schools. While one

witness commented that high levels of ethnicity might explain why 12 000

residents of Hume had left school under the age of 14 [10] it does not explain why north-west Tasmania had

the lowest school retention rates in the country. [11]

Another witness stated that the retraining of people with previously low

levels of educational attainment presented problems because many people

in rural Australia have not had pleasant experiences with the formal education

sector.' [12] The Committee considers

these observations to be somewhat disturbing as it suggests that the education

system is not adequately addressing the needs of regional communities,

particularly those from non-english speaking backgrounds.

1.19 In addition to the problem of skill shortages is the growing problem

of generational unemployment. As a witness from the Maryborough City Council

revealed:

We are now in a situation where we have a third generation of unemployed

people within the community. They know no different. As long as they

can remember, their grandfathers have not worked and their parents have

not worked, and they seem to feel that that is the way the system goes.

[13]

International Experience

1.20 The revitalisation of regions whose industrial base has been significantly

eroded has been a challenge faced by countries even more severely affected

than Australia by global economic change. Industrial and mining areas

of France and Belgium have borne the brunt of this change, as have the

English Midlands, the north-east `rustbelt' areas of the United States

around cities like Pittsburg and Baltimore and the Maritime Provinces

in Atlantic Canada.

1.21 These countries have implemented many and varied regional policies

over time. Some of these policies have resulted in marked improvements

in the regions concerned such as in the case of Birmingham in the UK (discussed

further in Chapter 2) while others have been less successful.

1.22 The Committee takes the view that in regions which have suffered

considerable economic decline and where prospects for substantial revitalisation

appear limited the solution should include appropriate social and economic

assistance involving both government and community sectors. At various

places throughout this report the Committee has drawn on international

examples of regional policy some of which are innovative and others illustrative

of the difficulties faced by governments in attempting to combat regional

decline.

Classification of regions and their problems

1.23 The Committee notes the very useful classification of Australian

regions made by the National Institute of Economic and Industry Research

(NIEIR). [14] A listing of the regional structure

adopted by the NIEIR can be found in Appendix 1. The six broad categories

identified are:

- sub-global cities – this is Sydney CBD and some surrounding

areas (North Shore and Eastern Suburbs) which are connected to major

business centres abroad and whose workforce is heavily engaged in maintaining

financial services and information links with centres of global business.

The NIEIR also suggest that the Melbourne and Brisbane CBDs have the

potential to become sub-global cities. Economic performance in these

regions is influenced by the state of the world economy and their continued

prosperity will depend on their ability to be attractive players in

the global market place.

- service based metropolitan – these are suburban areas

dependent on service industries, the government workforce and domestic

consumer industries. The NIEIR places the Central Coast, Outer West,

Sydney South, Sydney Central, Sydney Northern Peninsula, Perth Metropolitan

and Perth CBD, Brisbane north and south, Canberra, and Adelaide CBD

in this category. Economic performance in these regions has been influenced

by transport improvements, retail decentralisation, and government locational

strategies.

- resource based regions – these are areas or centres which

are largely dependent on the exploitation of local minerals, energy

resources and timber resources. Examples include Broken Hill, Gladstone

and the Pilbarra region. Economic performance in resource based regions

will be affected by movements in world prices as well as the stock of

natural resources.

- industrial oriented regions – these being areas with a

higher than national average concentration of manufacturing activity.

They include metropolitan areas like Sunshine, Footscray and Broadmeadow

in Melbourne, Liverpool and Auburn in Sydney as well as fringe metropolitan

centres like Elizabeth, Geelong and Kwinana. A significant factor in

the performance of these regions over the past fifteen years has been

the progressive removal of tariff protection.

- rural based regions – these being areas of population

largely dependent on agriculture and pastoral industries, examples being

Gippsland, Riverina, Darling Downs and other wheat belt areas and coastal

regions in all States. While climatic conditions can paly a significant

role in the short-term performance of these regions, over the longer-term

the leading influence has been the decline in the real value of commodity

prices.

- lifestyle based regions – these are almost always coastal

regions with very favourable climates which have experienced population

increases because of tourism and as places of retirement. Places such

as the Gold Coast, Sunshine Coast, Far North Coast (NSW) and North Queensland

fall into this category. Tourism and often eco-tourism plays a primary

role in the economic performance of these localities.

1.24 Cycles of economic growth have been the experience of regions for

a century. These vary from region to region and occur for different reasons,

part of which can be attributed to the differential industry distribution

as identified above. Industries experience product life cycles and technological

change which have an impact on labour demand. [15]

The demand for skilled labour, in some industries, is usually more crucial

at the setting-up stage of production and less so once production is in

full swing. This explains why a perceived shortage of skilled labour is

often an impediment to investment in non-metropolitan regions.

1.25 Changes to the profile of Australia's manufacturing industry have

had its greatest impact on regional centres dependent on a narrow industrial

base. This can be seen in a fall in employment resulting from the rapid

decline of the clothing, textile and footwear industry in north west Melbourne

and in Launceston. It can also be seen in the Spencer Gulf towns of Port

Pirie and Whyalla and in Burnie. Larger and more fortunately situated

centres like Geelong and Newcastle have been less affected by the decline

in their major industries because of their success in maintaining and

developing a broader industrial base.

1.26 Rural based regional economies have waxed and waned over the past

seventy years, but the trend has followed a steady decline with the diminishing

value of agricultural industry products as a proportion of GDP, similar

to the trend in more recent years with regard to non-metropolitan manufactured

goods. The pastoral and agricultural industries which were the foundation

of Australia's prosperity for most of its post-settlement history, were

not labour intensive, but the small towns and townships which serviced

properties in rural districts have gone into sharp decline as improvements

to roads and motor vehicles have brought dispersed populations and townships

closer to larger regional centres. Much of the so-called `rural decline'

in small country towns may be attributed to progress and to increasingly

sophisticated demands of the rural population for services available only

in the larger regional centres. As was stated in a paper delivered to

the Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand:

Some commentators view the pattern of settlement in many parts of rural

Australia as simply archaic, in the sense that it reflects the `horse

and buggy' era and has not adjusted to the new economy. The trend toward

centralisation away from small settlements and into larger provincial

centres, they would say, represents a natural progression and reflection

of consumer demand. Whilst in one sense this might be true, it does

not deal with the very real economic and social issues bearing down

on small towns. If the issues are ignored, we risk weakening the economic

and social fabric of the State and its capacity to compete. [16]

1.27 The economic and employment conditions in lifestyle based regions

such as the coastal regions of northern NSW and southern QLD varies greatly.

Some areas have experienced property booms, not always to the advantage

of local people. Retirement incomes are lower than wages and salaries

on average, as are the incomes of the working populations in these regions.

On top of this are the very high numbers of unemployed people in these

regions, in particular unskilled young people for whom `lifestyle' is

either a more important consideration than employment, or some compensation

for lack of employment prospects.

The plight of regional Australia

1.28 The Committee has heard a great deal of oral evidence and assimilated

a large volume of information, which taken together, present fairly gloomy

prospects for those living in some regions in Australia. These stark realities

facing a community in decline may be sequenced as follows:

- erosion of the economic base as key industries wind down or where

company restructuring forces the closure of a branch plant;

- closure of support industries;

- loss of income puts pressure on local small businesses, some of which

may close;

- as employment prospects recede school leavers and mobile skilled workers

depart for the metropolitan region, further education and training or

to regions with a skills deficit;

- population decline sees withdrawal of some state and Commonwealth

government offices and services;

- school numbers drop and professionally qualified (and higher paid)

people leave;

- housing prices fall, reducing the options for some of those with portable

skills, who may stay and accept unemployment benefits; and,

- local rates receipts fall, with a likely drop in services as a result.

[17]

1.29 This sequence shows the influence of negative income multipliers,

with reduced levels of income and local small business closures. In towns

that have been highly dependent on a single industry sector, such as in

Whyalla, there is a significant risk that following a period of sustained

high unemployment, the local labour supply will become out of touch with

the mainstream labour market. Skills atrophy and the stock of human capital

loses its value. Regional labour market perceptions change the institutional

framework of the local labour market to the extent that it presents a

deterrent to new business investment. This effect is compounded when a

decline in housing prices or rents attracts workers with poor employment

opportunities. [18]

1.30 Evidence given to the Committee indicates that wage levels are not

a significant factor in determining employment outcomes, but skill levels

are. Thus, firms in search of skilled workers will select a location with

low unemployment and bid for workers in the already tight market. [19]

It should also be noted that Australia experiences a relatively low incidence

of geographical labour mobility. On the basis of evidence given to it,

the Committee has identified deficiencies in public transport as presenting

a serious disadvantage to people in some metropolitan regions. Even advocates

of a minimalist government policy role for regional development put infrastructure

creation in the category of tasks which governments do well and which

they have continuing responsibility for. Expenditure on urban transport

over recent decades has been restricted, in most cities, to improvements

to existing routes rather than to building in new corridors to meet settlement

expansion and population shifts.

1.31 Another feature of some metropolitan regions are the permanent pockets

of high unemployment, broadly characterised as low-skilled workers, often

migrants with poor English language skills, or those living in non-metropolitan

regions recently bereft of obsolete and redundant industries. This is

further evidence of the inherent inadequacy of the education system for

people from non-english speaking backgrounds. Such areas indicate

the extent of the training deficit which needs to be overcome.

1.32 The Committee notes the efforts that are being put into `school-to-work'

transition programs, particularly in South Australia and in Western Australia:

measures intended to fit school leavers into local jobs and to combat

the risk of `generational unemployment' of which the Committee heard much

evidence. Some evidence was heard of misconceptions about the changed

world of work, [20] negative attitudes to education,

and the need to address the challenge of local relevance and motivation.

There are also resource deficiencies. In the midst of the rationalisation

of services which is currently experienced across all sectors, that which

the country can least afford is a restriction of educational opportunity,

particularly in the area of vocational education. Chapter 5 of this report

details the Committee's findings and recommendations in regard to education

and training.

1.33 Despite the difficulties facing regional communities, the Committee

still found strong indications of optimism and stories of success in its

visits to rural regions; they are `battling' but they are still optimistic.

Communities were determined to survive on new, less certain and less lucrative

industries even though their populations were declining with their children

heading for the cities. The community spirit of a region, or of towns

and cities in the region, is an important element for future or continued

growth given the right form of government funding assistance.

1.34 At the public hearing in Elizabeth, the Committee heard from the

Deputy Mayor of the City of Playford, Mr Ronald Watts, that the region

believed in its economic future:

If you travel around the northern suburbs of Adelaide, and this is

not just Elizabeth; it is Salisbury as well, you will find a very positive

attitude from the people that live here. There is a bright economic

future, in our view. We do believe in our own ability to make things

change and to work. We are not sitting around waiting for someone to

come and give us a handout. We will obviously take your money because

we need it but we will make every effort to take our own attempts forward

and not sit back to wait for someone to do something about it. [21]

1.35 This attitude appeared to be paying dividends in some areas of South

Australia where economic restructuring has taken a significant toll on

traditional areas of employment. The Committee heard evidence from representatives

of the Riverland Development Corporation of successful industry diversification

leading to improved long-term prospects for regional growth. Between June

1992 and March 1997 the unemployment rate in the region declined from

15.7 per cent to 6.9 per cent. It was explained that this decline correlated

with a period of strong economic growth. It was also explained, however,

that industry restructuring and government assistance, particularly in

the area of infrastructure, played a significant role. Faced with a shift

in demand in the citrus industry, the Riverland region has expanded its

horticultural base with the wine industry seen as the critical new industry,

notwithstanding the significant value of growth in almond, vegetable and

olive production. [22]

1.36 A representative of the Eyre Regional Development Board in Whyalla

presented similar evidence to the Committee. In this region, it was explained

that while agriculture would continue to be a major source of economic

growth for the region, it would not generate significant employment growth.

Thus the region was working at developing its tourism, viticulture and

aquaculture industries. It was stressed that in fostering these new industries,

government had an important role to play in ensuring that appropriate

and adequate infrastructure was available. [23]

1.37 The task of the Committee has been to identify those problems in

the regions which may be addressed in a constructive way and those difficulties

and grievances which may be remedied by the actions of governments. The

Committee understands the economic basis for the decline in regional employment

opportunities. It appreciates the pressures on Australian enterprises

to rationalise workforces and maximise profits in order to become players

in the global market and to satisfy the demands of shareholders and the

stockmarket. It also appreciates that these developments are associated

with some heavy social costs, and does not accept the proposition that

in addressing these social costs governments must take their cue from

the operational culture of the private sector.

1.38 A more detailed discussion of regional diversification and the impacts

of government policy and structural change on regional growth is provided

in Appendix 2 of this report. This appendix provides a case study of the

Northern Rivers region of New South Wales, presenting the cumulative evidence

given to the Committee on regional development issues in this area.

City and `the bush': a hard-dying perception

1.39 There is no accepted definition of a `region' in the academic literature.

Most studies done on regionalism, including those commissioned by government

agencies make no distinction between metropolitan and non-metropolitan

regions. For instance, the Bureau of Industry Economics (BIE) argued in

its 1994 report, Regional Development: Patterns and Policy Implications,

[24] that regional policy ought to be developed

in a way which treated all regions, metro and non-metro, in the

same way so that disparities could be assessed. While the BIE found that

between 1976 and 1986, non-metropolitan regions in Tasmania, Victoria

and South Australia suffered the greatest relative declines in income,

Hobart, Melbourne and Adelaide also suffered relative declines. On this

basis, the submission from the south Metropolitan Perth Regional Development

Organisation also argued that it makes no theoretical or practical sense

to restrict regional policy to dealing only with non-metropolitan regions.

[25]

1.40 The Committee, following the current practice, has taken a broad

definition of the term `region'. This reflects the view that regions are

most appropriately defined according to measurable indicators of economic

and employment performance, and descriptions of economic synergies. Regions

include not only those areas of population outside the metropolitan cities,

but large districts within metropolitan areas beyond the central business

districts. The Committee, nonetheless, has some sympathy with the view

from rural regions that the emphasis on a broad view of regional Australia

would cast the more traditionally defined regions into the shadows [26]

and that social and cultural determinants should be seen as just as important

as economic determinants.

1.41 The tensions between metropolitan and non-metropolitan interests

are long-standing. They inspired the foundation of the Country (National)

Party in 1920 and fuelled the One Nation Party nearly eighty years after.

The two events are not unconnected. The traditional distinction between

`Sydney and the bush' which has featured prominently as a theme in Australian

arts and letters has changed, especially since the mid-1980s, to a distinction

between `the big end of town' and beyond. That is, a perception has developed

of a new and close alliance between governments and business, whose decisions

about the economic structure of the nation have resulted in declining

prosperity and a diminished level of services in the regions (including

outer metropolitan regions) as well as an increasing sense of neglect

and alienation. This sentiment has been well-described by Margaret Bowman

in the foreword to a series of studies on rural towns:

The communities described here may be geographically `beyond the city',

but they remain within its shadow, in the main under the control of

city-based social, political and economic forces which most residents

can neither control nor even understand. Country towns take their cues

from the city: what the trend setting suburb has today the rural centre

tomorrow will be working to acquire…But in other important respects,

non-metropolitan Australia is another nation…Life is harsher because

there are, at best, fewer social choices and often facilities and services

lack the quality and variety of the city. Vulnerability to external

forces breeds uncertainty, isolation begets fear of the city, and there

is the constant awareness that the city acts as a magnet to some of

the most talented and ambitious young people. [27]

1.42 Among these `external forces' are corporations and governments.

The corporations, especially in the retail industry, represent the face

of the city in the regions. With their economic strength they can destroy

local business, and also deprive rural centres of services that cannot

be provided locally. Governments have provided a protective counterforce

in the past, and regional communities have long been dependent on the

highly visible arms of government agencies, so that the extent of their

recent withdrawal has been traumatic. There is a perception that the decision

to reduce government services in regional areas has been at least partly

influenced by business models of administration which are not always appropriate

for the delivery of those services traditionally provided by governments.

1.43 The misgivings of some critics to a definition of regions which

excludes metropolitan areas may result from past experience in which regional

development policy was associated with efforts, with mixed success, to

decentralise economic activity away from metropolitan areas. [28]

It is also based on the idea that people who live and work in rural areas

form a cohesive group with particular needs and who are capable of exercising

political influence to achieve them. People living in the vast outer fringes

of metropolitan areas naturally see things differently. These regions

are the dominant centres of economic activity and contain about 80 per

cent of Australia's population.

1.44 The Committee notes that some scholars view the traditional distinction

between the city and the bush as a false dichotomy: that there is an overwhelming

commonality of interests between people who live in the metropolitan areas

and those who live beyond them. [29] Nonetheless,

the Committee considers that recent global trends, reflected in changing

government policies, are strengthening rather than diminishing the force

of rural mythology as may be evidenced by recent political developments.

1.45 However one may regard the `city and the bush' dichotomy, the evidence

presented to the Committee gives a clear picture of the importance of

metropolitan regions as areas of production and employment relative to

non-metropolitan regions. A view expressed in a submission from a rural-based

researcher, Professor Tony Sorensen, argued that government incentives

and training activities should not be restricted to rural and regional

areas.

I am inclined to the view that such activities should be national and

not regional since capital cities need similar conditions to rural and

regional areas to prosper. Dynamic and energetic capital cities will

create significant spill-over effects that benefit adjacent non-metropolitan

regions and diversify parts of regional Australia away from reliance

on traditional primary output. [30]

1.46 A social aspect to support for metropolitan regions was stated at

the Committee's hearing in Perth:

I believe that unemployment in metropolitan regions probably can have

a greater impact on the social cohesion of a metropolitan community

than in rural communities, because in rural communities, from my observation,

there is a greater support structure … that varies greatly …

from metropolitan communities, which in some cases comprise a lot of

strangers just grouped in a suburb and doing the best they can. [31]

1.47 The Committee was informed of the disparity between the northern

and southern metropolitan areas of Perth, exacerbated in part by the neglect

by successive governments of rail transport links in the south and by

high council rates. [32] The geographical focus

of regional development programs run by the government of Western Australia

is the rural areas. Metropolitan areas are not eligible for the range

of assistance programs for economic development which are intended to

ensure that communities in rural areas are not disadvantaged relative

to those in Perth. While the Committee sees some virtue in needs based

funding it also recognises the policy dilemma faced by governments which

receive sound advice that development funding can have proportionally

greater benefit in metropolitan regions through significant employment

gains. [33]

Social and physical infrastructure

1.48 The Committee was told that governments have failed to link effectively

the development of local infrastructure to training and work experience

opportunities for unemployed people. Many councils need support and encouragement

from both the state and Commonwealth governments to develop the frameworks,

concepts, plans (detailed designs in the case of infrastructure projects)

and budget allocations to tailor projects to have maximum community, training

and job placement outcomes. The Committee was informed by one council

that there seems to be a misguided notion on the part of governments of

all persuasions that just because they have an idea to get the unemployed

working that councils are going to be queuing to take advantage of it.

[34] The Committee is aware, however, of example

were local governments have enthusiastically taken up policies to help

generate employment in the local area.

1.49 Some metropolitan regions showed evidence of problems of an even

greater magnitude than non-metropolitan regions. The City of Maribyrnong

described its deteriorating infrastructure, on which it is now spending

twice the Melbourne metropolitan municipal average. The Maribyrnong Council

was critical of the failure to link infrastructure renewal with job training

opportunities. [35]

1.50 The Committee heard a more complex explanation in relation to employment

in the western suburbs of Sydney where Fairfield and Liverpool councils

have been energetic in the creation of new jobs, but with little improvement

so far in the unemployment rate. Professor Bob Fagan explained to the

Committee his research into the segmentation of the labour force, and

how people become trapped into particular types of jobs or unemployment.

People find local jobs hard to access because of deficiencies in local

transport, especially for shift-work, or because of language difficulties.

[36]

1.51 The factor keeping people out of the workforce, out of jobs that

exist in their own commuting zones, is their inability to access various

kinds of social infrastructure – educational institutions, childcare

and so on. [37] The creation of a stock of

local jobs is only half the answer. The other is the creation of services

which will allow people to take up these jobs. As Professor Fagan pointed

out, the social infrastructure deficiencies result from decisions made

outside the region.

They are determined at state government level, they are determined

by patterns of investment by state and federal government, and they

are determined by, if you like, a lack of regional sensitivity in policies

that are not regional policies but welfare policies, employment policies,

industry policies and so on. [38]

Government actions and responsibilities

1.52 A line in the Budget Papers for 1997-98 puts the government's policy

on regional matters at that time very concisely:

In 1997-98 the Commonwealth terminated regional development programs

to eliminate duplication of State and local government activities in

this area.

1.53 As noted, however, the Government has since given a higher priority

to regional development issues, strengthening its regional services portfolio,

expanding the role of the Area Consultative Committees and, as will be

outlined in Chapter 6, implementing some other regional development initiatives.

At its basis, however, Coalition regional policy is seen as an adjunct

to broader economic policy. The government claims that `getting the fundamentals

right' is the first and necessary step to the regeneration of regional

economies and employment. The Committee has no argument with `getting

the fundamentals right.' It does question the assumption that regions

will share in the benefits of national economic revival when so far all

the evidence points to the reverse. It takes the view that government

policy must become more proactive in the interests of regional Australia.

1.54 The Committee does not lack an understanding of the difficulties

and dilemmas that face the current government because they have faced

all previous governments. It also recognises that regional policy is not

an area where partisan boasts of long-term successes can be made by either

side of politics. As the Committee has noted already, the influence of

governments on many of the key factors impacting on regional areas is

limited. So much energy and resources with regard to regional issues is

tied up with the fight for markets, the application of flood or drought

relief and the scores of palliative measures that are required to keep

regional populations from falling behind their metropolitan kinfolk in

the equity stakes.

1.55 The Committee sees no end to the need for palliative measures in

parts of regional Australia. While the Committee accepts that some industries

will go out of existence and towns may go with them, there is in some

cases a justifiable cost involved in reviving the fortunes and the livelihoods

of localities and regions where economic and social benefits may be identified.

1.56 Economic and social planning should not be seen as incompatible

with either deregulation or micro-economic reform. There is neither national

economic benefit nor social benefit in having depressed regions remain

in existence in the midst of overall prosperity. Some attempt at planning

should be made to ensure that the redistribution of wealth and resources

gives a better than even chance that prosperity will be extended beyond

the fortunate few regions that currently experience growth.

1.57 The Committee believes that there is now the need for the Commonwealth

to continue its recent moves in creating a more proactive role for itself

in regional policy making. The core of this policy should be the establishment

of a more formal structure of consultation and decision making across

states, and embracing both state and local governments in the process.

The Committee argues that proper consideration of `bottom-up' proposals

and solutions, and facilitation of local business initiatives, would benefit

from a coordinating structure which embraced all three spheres of government.

At first glance this proposal presents a paradox: centralised `top-down'

structures may appear to be least suitable for encouraging local enterprise.

The first response to this is that the Commonwealth already has structures

in place for this purpose in the Area Consultative Committees. The second

is that the notion of a formally constituted federal coordinating body

would build primarily upon existing state structures rather than impose

a Commonwealth model, incorporating the Area Consultative Committees in

some overarching structure. The Committee is firm in its view that the

complaints of regional and local agencies and businesses about uncoordinated

assistance and initiatives from both Commonwealth and state governments

should be addressed in a practical way. It looks to the government's proposed

Regional Australian Summit to advance this process.

Footnotes

[1] McKinsey and Co. Lead Local Complete

Global: Unlocking the Growth Potential of Australia's Regions, Office

of regional Development, Department of Housing and Regional Development,

1994

[2] Report of the Taskforce on Regional Development,

Developing Australia: A Regional Perspective, Canberra, 1994

[3] Peter McLoughlin and James Cannon in R.

Hughes and P D Wilde, (eds) Industrial Transformation in Australia

and Canada, pp. 267-68

[4] McKinsey and Company, Lead Local Compete

Global: Unlocking the Growth Potential of Australia's Regions, Report

for the Department of Transport and Regional Development, Canberra, 1994,

p.25

[5] Submission No. 183, Department of Transport

and Regional Development, vol. 8, p. 91

[6] Submission No. 110, South Metropolitan Perth

Regional Development Organisation, vol. 5, p. 17

[7] Submission No. 202, South Australian Government,

vol. 9, p. 230

[8] Submission No. 166, Department of Employment,

Education, Training and Youth Affairs, vol. 7, p. 99

[9] Professor Rolf Gerritsen, Hansard,

Canberra, 18 December 1998, p.1510

[10] Mr David Hall, Hansard, Ballarat,

17 June 1998, p. 630

[11] Mr Dick Adams MP, Hansard, Launceston,

16 June 1998, p. 506

[12] Dr Ian Falk, Hansard, Launceston,

16 June 1998, p. 496

[13] Cr Alan Brown, Hansard, Rockhampton,

4 August 1998, pp. 1182-3

[14] Graham Larcombe and Mark Cole, `Australian

Regional Employment and Growth Trends, Prospects and strategies' in National

Economic Review, No.90, March 1998, pp.19-20

[15] Submission No. 110, South Metropolitan

Perth Regional Development Organisation, vol. 5, pp. 24-5

[16] Peter Tesdorpf, Competitive Communities…?

The Impact of Competitive Tendering and National Competition Policy on

Small Towns, Small Business, Economic and Regional Development –

the Victorian Experience, Paper delivered to the Small Enterprise

Association of Australia and New Zealand Annual Conference, 21-23 September

1997, p.10

[17] McKinsey & Company, Lead Local

Compete Global: Unlocking the Growth Potential of Australia's Regions,

Report for the Department of Industry, Transport and Regional Development,

Canberra 1994

[18] Submission No. 110, South Metropolitan

Perth Regional Development Organisation, vol. 5, p. 21

[19] ibid., p. 51

[20] Submission No. 51, Enterprise in the Community,

vol. 2, p. 163

[21] Mr Ronald Watts, Hansard, Elizabeth,

28 April 1998, p. 105

[22] Mr Kenneth Smith and Mr Trent Madder,

Hansard, Elizabeth, 28 April 1998, pp. 81-6

[23] Mr Ian Nightingale, Hansard, Whyalla,

29 April 1998, pp. 137-8

[24] Bureau of Industry Economics, Regional

Development: Patterns and Policy Implications, Research Report 56,

Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra 1994.

[25] Submission No. 110, South Metropolitan

Perth Regional Development Organisation, vol. 5, p. 13

[26] Submission No. 36, Orange City Council,

vol. 2, pp. 2-3

[27] Margaret Bowman (ed.), Beyond the City:

Case Studies in Community Structure and Development, Longman Cheshire

Melbourne 1981, p. xxvi

[28] Submission No. 110, South Metropolitan

Perth Regional Development Organisation, vol. 5, p. 9

[29] D. J. Walmsley, `The Policy Environment'

in Tony Sorensen and Roger Epps (eds.), Prospects and Policies for

Rural Australia, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne 1993, p. 55

[30] Submission No. 72, Associate Professor

Tony Sorensen, vol. 3, p. 290

[31] Mr Henry Zelones, Hansard, Perth,

18 August 1998, p. 1407

[32] ibid., p. 1415

[33] Submission No. 110, South Metropolitan

Perth Regional Development Organisation, vol.5, p. 11

[34] Submission No. 118, Maribrynong City Council,

vol. 5, p. 194

[35] ibid., pp. 193-4

[36] Professor Robert Fagan, Hansard,

Parramatta, 23 July 1998, p. 1038

[37] ibid., p. 1039

[38] Professor Robert Fagan, Hansard,

Parramatta, 23 July 1998, p. 1039