Chapter 3

The premise of the bill

3.1

This chapter focuses on the claim made by the drafter of the legislation

that the need for action on creeping acquisitions reflects the Australian

Competition and Consumer Commission's (ACCC) highly permissive approach to

merger applications.

The high rate of merger approval

3.2

The principal argument put by the proponent of the bill to amend section

50(1) is that the current rate of merger approvals by the Australian

Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is too high. Associate Professor

Frank Zumbo argues that the ACCC approves 97 per cent of all merger and

acquisition applications and that as a result, 'Australia has some of the most

highly concentrated markets in the world'.[1]

3.3

In evidence to the committee, Associate Professor Zumbo explained how

the figure of 97 per cent was calculated:

In the year 2008-09 there were 412 mergers considered. The

number not opposed outright was 397; opposed outright, 10. When I get to around

the 97 per cent figure I look at the number totally opposed outright. On that

number, 10 out of 412, you get 97.57 per cent. There is a further category—and

I add this for the sake of clarification—that says ‘applications resolved

during review through undertakings’. That represents a further five cases. That

is a case where the ACCC has raised concern and the parties have given

undertakings to the ACCC that satisfy the ACCC. That is a further five. Even if

you add that further five as having been stopped by the substantial lessening

of competition test, then that is a further one per cent. That takes you down

to roughly 96.57 per cent. So, the 97 per cent number is looking at the opposed

outright, but I do accept that there is some flexibility and I am happy to

throw in those extra five or that extra per cent and you are still around 97

per cent.[2]

Criticism of this analysis

3.4

Both Treasury and the ACCC have queried Associate Professor Zumbo's

analysis. The following section canvasses their respective arguments.

Treasury's analysis

3.5

In its submission, Treasury noted that the percentage of mergers opposed

and not opposed is not a good measure of the effectiveness or application of

the merger test because some merger matters are not included in the official

statistics.

3.6

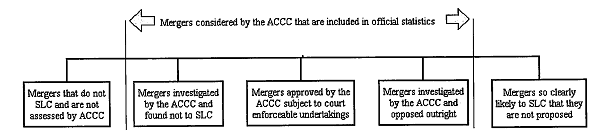

Treasury's submission included the above diagram by way of illustration.

The boxes on the far left and far right of the spectrum represent those merger

categories that are excluded from the official statistics.

3.7

The far left box represents those mergers that do not substantially

lessen competition and are not assessed by the ACCC. A large proportion of the

merger matters that are considered but not opposed by the ACCC are referred to

it by the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) or the Australian Prudential

Regulatory Authority (APRA) or by the merger parties as a matter of courtesy.

These do not raise competition concerns.

3.8

The far right box represents those mergers so likely to substantially

lessen competition that they are not proposed. These mergers are prevented by

section 50(1) 'even though they are not recorded as having been proposed by the

ACCC'.[3]

3.9

The three middle boxes are those mergers that are considered by the ACCC

and are either found not to substantially lessen competition, are approved

subject to enforceable court undertakings or are opposed outright.[4]

3.10

Associate Professor Zumbo did note that the mergers included in the

official statistics and those so 'likely to substantially lessen competition

that they are not proposed' are more likely to arise in concentrated markets.

He told the committee that in a highly fragmented market, the parties are

unlikely to go to the ACCC unless they want 'a letter of comfort'.[5]

3.11

Nonetheless, the key point to make is that if those mergers in highly

fragmented markets represented in the far left box were included in Professor

Zumbo's calculations, the merger approval figure would be significantly less

than 97 per cent.

3.12

The ACCC was also critical of Associate Professor Zumbo's merger

approval statistic of 97 per cent. Mr Tim Grimwade of the ACCC told the committee

that the figure of 97 per cent cannot be a meaningful measure of the

effectiveness of the test. He gave three main reasons why this is the case.

3.13

First, it does not take into account the nature of the matters that the

ACCC reviews. Specifically, there are many merger clearance requests—'between

100 and 200 a year'—referred to the ACCC by the FIRB. The vast majority of

these raise no concerns 'because they relate usually to a new entrant coming in

and buying an asset or business in Australia'. Mr Grimwade noted that

these instances:

...clearly would inflate the denominator, if you are going to

start using a 97 per cent statistic to measure the effectiveness of the test.[6]

3.14

Second, there are matters that do not require review and important sub‑categories

among those that do require a review. The ACCC explained that in this financial

year it has sought to distinguish between pre-assessed mergers that do not

require any review and those that do. In the 2009–2010 financial year, about

120 merger requests have been pre-assessed without any review, leaving 'about

118' that require review.[7]

Of those requiring review:

- some are opposed outright;

- some are accepted that would otherwise have been blocked but for

a remedy being proposed and accepted by the commission; and

- some are put for review but 'withdrawn before we give our final

decision'. There were 'around 21' of this category last year and 'another 10

already' this financial year.[8]

These categories

accord with the three middle boxes in Treasury's diagram (above).

3.2

Third, the ACCC emphasised that there is no legal obligation by parties

to notify the Commission of a merger proposal. Instead, the ACCC structures and

incentivises notifications 'to capture a really large number of mergers' in

order to ensure that it can block any anticompetitive merger. Mr Grimwade

explained:

If we had a mandatory notification process—and we have given

it some thought—it would have all sorts of adverse consequences. For instance,

it would send a signal to those that do not meet the notification

thresholds—because you have to have a threshold for notification—that perhaps

their merger is okay when in fact it might not be.[9]

3.3

The ACCC was asked its view as to how many mergers and acquisitions are

prevented by the substantial lessening of competition test. Mr Grimwade gave

the following response:

...having regard to the matters that we review, leaving aside

the matters we do not review that we pre-assess do not require review, and you

include the matters we oppose, the matters we would have opposed but for

accepting a remedy or the matters that were withdrawn, you end up this

financial year looking at about 77 per cent, I think. I think it is a furphy to

use a statistic like that to make such a big decision on changing a test of this

function effectively for two decades that is consistent with international best

practice and has largely generated very good outcomes for the Australian

economy.[10]

International comparisons

3.15

Ms Julie Clarke of Deakin University has argued that the approval of

roughly 95 per cent of merger proposals notified to the ACCC in any given year

does not necessarily mean that the 'substantial lessening of competition test'

is set too high. Indeed, she noted in her submission to the inquiry that this:

...percentage is consistent with the percentage of notified

mergers challenged in most other OECD jurisdictions. In the United States, for

example, the percentage of notified mergers challenged is routinely lower than

that challenged in Australia. This statistic simply reflects the fact that the

vast majority of mergers do not raise competition concerns. It does not imply

that the law itself is too lenient.[11]

3.16

Associate Professor Zumbo told the committee that comparisons of merger

approvals between Australia and the United States must be seen in context. He

explained:

Our concern in Australia is that our markets are getting even

more concentrated and quickly so. If you have a 97 per cent approval rating in

the United States, which is a much bigger market, it takes a lot longer to get

to the level of concentrations that you have in Australia if it is the same

approval rating of 97 per cent. We need to look at each country on its own

merits, as we have to look at each merger on its own merits.[12]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page