<<

Return to previous page | House of

Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Affairs

Navigation: Previous

Page | Contents | Next Page

- The disproportionately high level of Indigenous juveniles (aged

between 10 and 17 years) and young adults (aged between 18 and 24

years) in the criminal justice system is a major challenge

confronting the Council of Australian Government’s

(COAG’s) commitment to 'Closing the Gap' in Indigenous

disadvantage.

- Tragically, Indigenous juveniles and young adults are more

likely to be incarcerated today than at any other time since the

release of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody

final report in 1991. This rise has occurred despite increased

funding and the concern and efforts of community members,

government officials, non-government organisations and the

judiciary around Australia.

- Contact with the criminal justice system represents a symptom

of the broader social and economic disadvantage faced by many

Indigenous people in Australia. We have reached the point of

intergenerational family dysfunction in many Indigenous

communities, with problems of domestic violence, alcohol and drug

abuse, inadequate housing, poor health and school attendance, and a

lack of job skills and employment opportunities impacting on the

next generation of Indigenous Australians. Additionally, there has

been a loss of cultural knowledge in many Indigenous communities,

which has disrupted traditional values and norms of appropriate

social behaviour from being transferred from one generation to the

next.

- The overrepresentation of Indigenous youth in the criminal

justice system is a national crisis and Commonwealth, state and

territory governments must respond rapidly and effectively to

prevent current and future generations of young Indigenous people

from entering into the criminal justice system. This is a long term

challenge that will require sustained commitment and rigour from

all jurisdictions to address the root causes of Indigenous

disadvantage, and to rehabilitate young Indigenous people currently

in the criminal justice system.

The critical need for early intervention

- The detention rate for Indigenous juveniles is 397 per 100 000,

which is 28 times higher than the rate for non-Indigenous juveniles

(14 per 100 000). In 2007, Indigenous juveniles accounted for 59

percent of the total juvenile detention population.[1]

- There is a strong link between the disproportionate rates of

juvenile detention and the disproportionate rates of adult

imprisonment. Although Indigenous Australians make up only

approximately 2.5 percent of the population, 25 percent of

prisoners in Australia are Indigenous.[2]

- Prisoner census data shows that between 2000 and 2010, the

number of both Indigenous men and women in custody has increased

markedly:

- Indigenous men by 55 percent, and

- Indigenous women by 47 percent.[3]

- The Committee finds that the escalation of the number of

Indigenous women in detention is disturbing. Indigenous women are

critical to the future strength of Indigenous families and

communities. They play an important role in the care of children,

providing the future generation with a stable upbringing. Continued

growth in the number of Indigenous women being imprisoned will have

a long lasting and negative impact on the wellbeing of Indigenous

families and communities.

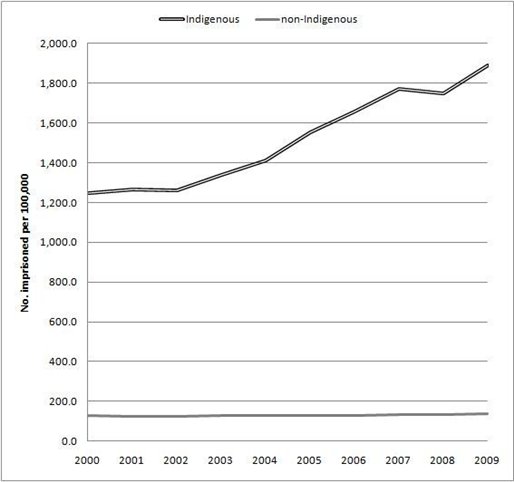

- Between 2000 and 2009, the imprisonment rate of Indigenous

Australians increased 66 percent (from 1 248 to 1 891 per 100 000).

Figure 2.1 shows this dramatic increase in the rate of imprisonment

for Indigenous people over the last decade, in comparison to a

steady imprisonment rate for non-Indigenous Australians. These

figures highlight both a concerning pattern of generational

entrenchment for some Indigenous Australians in the criminal

justice system over a long period of time, and the critical need

for early intervention.[4]

Figure 2.1 Age standardised Indigenous

and non-Indigenous imprisonment rates in Australia

(2000‑09)[5]

Source ABS 2009, Prisoners in Australia

4517.0, Canberra.

- Statistics demonstrate that adult imprisonment rates differ

between states and territories (see Figure 2.2).

- New South Wales has the highest total number of Indigenous

people in prison (2 139), compared with Western Australia (1 552)

and Queensland (1 495). However Figure 2.2 shows that Western

Australia has the highest number of Indigenous people in prison per

capita than any other state or territory, increasing from 2155.7

per 100 000 in 1999 to 3 328.7 per 100 000 in 2009. That figure

represents at least three Indigenous people in jail for every 100

Western Australian residents.

Figure 2.2 Age standardised per capita

Indigenous imprisonment rates by state and territory, 1999-2009

Source ABS 2009, Prisoners in Australia

4517.0, Canberra.

- The steepest increase in Indigenous imprisonment rates in the

2000-09 period was 90 percent for the Northern Territory, while

significant increases were recorded in South Australia (65

percent), New South Wales (57 percent), Western Australia (54

percent), Victoria (50 percent), and Queensland (23

percent).[6]

- Indigenous juveniles and young adults are much more likely to

come into contact with the police in comparison with their

non-Indigenous counterparts. In 2008, over 40 percent of all

Indigenous men in Australia reported having been charged formally

with an offence by police before they reached the age of

25.[7]

- Indigenous juveniles are overrepresented in both community and

detention-based supervision. Indigenous juveniles make up 53

percent of all juveniles in detention and 39 percent under

community supervision. Indigenous juveniles in detention are

younger on average than their non-Indigenous counterparts.

Twenty-two percent of Indigenous juveniles in detention were aged

14 years or less, compared with 14 percent of non-Indigenous

juveniles.[8]

- The overrepresentation of Indigenous juveniles in the criminal

justice system varies greatly according to state and territory,

offence type and by the type of interaction (including being

cautioned, charged or detained). However, data is not presently

available to accurately compare types of contact across state and

territory jurisdictions. The Australian Institute of Criminology

(AIC) found that differing levels of representation can partly be

attributed to different counting measures to record contact with

the police across jurisdictions. The AIC recognised that data

relating to the Indigenous status of juveniles may not adequately

capture the extent of Indigenous juveniles’ contact with the

criminal justice system.[9]

- Adverse contact with the criminal justice system is not

confined to offenders. Community safety is a vital pre-condition to

achieve COAG’s targets in health, education and housing.

Governments agreed at a 2009 roundtable on Indigenous community

safety that if there is not action to address serious problems in

community safety, it will not be possible to make improvements in

other areas.[10]

- Indigenous people are more likely to be victims of crime,

especially violent crime, than non-Indigenous people.[11] Women are more likely to

be the victims of crime than men, and most violent offending

against Indigenous women is committed by Indigenous men.[12]

- Between 2006 and 2007, Indigenous women were 35 times more

likely to be hospitalised as a result of spouse or partner violence

than non-Indigenous women.[13]

- The Committee recognises that Indigenous victimisation rates

must be addressed in conjuncture with offending rates, and that

both are symptoms of the disadvantage and social dysfunction that

pervades many Indigenous communities.

- The Committee found that gaps in data collection are impeding

government responses to this issue, and that better data is needed

to track trends and better identify patterns of offending and

victimisation. A discussion of the relevant gaps in data collection

is included in chapter 8 of this report.

High rates of offending and disadvantage

- Prominent amongst the reasons for the high proportion of

Indigenous people in the criminal justice system is the broader

social and economic disadvantage faced by many Indigenous people.

An analysis of the 2002 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) identified a number of economic

and social factors that underpin Indigenous contact with the

criminal justice system. The analysis demonstrated that respondents

to the national survey were far more likely to have been charged

with, or imprisoned for, an offence if they left school early or

performed poorly at school, were unemployed, or abused drugs or

alcohol. The study found that the risk of Indigenous people being

charged or imprisoned increased if the respondent was experiencing

financial stress, lived in a crowded household, or had been taken

away from their natural family.[14]

- One of the key findings of the 1991 Royal Commission was

that:

The more fundamental causes of over-representation of Aboriginal

people in custody are not to be found in the criminal justice

system but those factors which bring Aboriginal people into

conflict with the criminal justice system in the first place ...

[and] the most significant contributing factor is the disadvantaged

and unequal position in which Aboriginal people find themselves in

society - socially, economically and culturally.[15]

- This section provides a brief discussion and general overview

of the relationship between aspects of disadvantage and the

overrepresentation of Indigenous juveniles and young adults in the

criminal justice system based on the evidence gathered in this

inquiry, including:

- social norms and individual family dysfunction

- connection to community and culture

- health

- education

- employment, and

- accommodation

Social norms and family dysfunction

- FaHCSIA’s submission stressed that individual family

dysfunction was a significant contributing factor to high rates of

juvenile offending and identified the following key concerns:

- The extent of alcohol abuse and consequential problems such as

family breakdown, family violence, financial and legal problems,

child abuse and neglect and psychological distress among family and

friends of the drinker

- There is a strong link between alcohol consumption and drug

misuse and the risk of imprisonment

- A further consequence of alcohol misuse is an increase in the

risk of Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), which itself is

linked to a range of long term behavioural problems

- The presence of family violence. This is a strong predictor of

child abuse, and partner violence has a damaging effect on

children's emotional, behavioural and cognitive development. Family

violence is strongly associated with a high risk of clinically

significant emotional or behavioural difficulties in Indigenous

children, and

- Child neglect and abuse.[16]

The Courts Administration Authority (CAA) of South Australia

reported in its submission that the link between child abuse and

neglect, and offending behaviour is now well established. The CAA

urged that:

The proven impact of child abuse and neglect on youth offending

suggests that prevention strategies and effective intervention in

child abuse and neglect should be priority areas for youth crime

prevention.[17]

- Chapter 3 discusses family dysfunction and negative social

norms, which are characteristic of the background of many young

Indigenous youth who find themselves in contact with the criminal

justice system.

Connection to community and culture

- Through a variety of historical processes, many young

Indigenous people risk becoming disconnected from their families

and their elders, language, law and country. This represents a loss

of wellbeing, accountability and culture, as norms of appropriate

social and cultural behaviour are not transferred from one

generation of people to the next. Many young Indigenous people risk

being caught between two worlds, as Anthony Watson (a Yiriman

cultural boss) explained:

It’s not having a sense of direction that is such a

problem. A lot of young people live in another culture; it’s

not mainstream, it’s not traditional; they are lost in the

wind. When they’re lost in the wind is when they could end up

in jail; they could end up dead, end up not contributing anything

to the community, but becoming a lot of trouble.[18]

- Chapter 3 of this report provides a discussion of the evidence

relating to community and family development of positive social

norms and positive social engagement, while chapter 7 examines a

number of diversion programs that incorporate Indigenous cultural

knowledge, norms and values.

Health

- The Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage Key Indicators 2009

Report found that:

Indigenous people experience very high rates of a variety of

physical and mental illnesses, which contribute to poorer quality

of life and higher mortality rates. Physical health outcomes can be

related to various factors, including a healthy living environment,

access to health services, and lifestyle choices. Health risk

behaviours, such as smoking and poor diet, are strongly associated

with many aspects of socioeconomic disadvantage. Mental health

issues can be related to a complex range of medical issues,

historical factors, the stressors associated with entrenched

disadvantage and drug and substance misuse.[19]

- A range of physical and mental health issues directly relate

and contribute to the overrepresentation of Indigenous youth in the

criminal justice system. The Committee has heard evidence that

these concerns include:

- mental health issues

- alcohol, drug and substance misuse [20]

- foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), and

- hearing loss.

- The Royal Australasian College of Physicians informed the

Committee that young people in the justice system are much more

likely to suffer from mental health disorders than the general

population. In addition, the College advised that:

Indigenous Australians are also more likely to have higher

hospital admissions for conditions classified as ‘mental and

behavioural disorders’ and have higher rates of suicide and

deliberate self injury than non-Indigenous Australians.[21]

- The College further noted that:

- Young people who have a childhood history of social and

psychological adversity are more likely to abuse alcohol and

illicit drugs; and

- Mental disorders due to psychoactive substance use are

reportedly diagnosed in Indigenous Australians at a greater

frequency than the general population. [22]

- Clearly alcohol, drug and substance abuse contributes to young

people coming into adverse contact with the criminal justice

system. In New South Wales, a study reported that, on average,

detained youth began to use substances for non-medical purposes at

11 years and commenced using illicit drugs about two years

later.[23] Related

research found that 63 percent of detained youth had engaged in

binge drinking in the two weeks prior to being detained, while 56

percent had used amphetamines, 50 percent had used opioids, and 24

percent had injected an illicit drug.[24]

- An analysis of the 2002 NATSISS found that illicit drug use and

high risk alcohol consumption were the strongest predictors of both

criminal prosecution and imprisonment.[25]

- Alcohol misuse has harmful and often tragic consequences across

generations of people. FASD describes a range of permanent birth

defects caused by the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy.

Primarily, prenatal alcohol exposure causes damage to the central

nervous system and is linked to growth deficiencies (low birth

weight) and facial abnormalities. The Committee has heard that the

incidence of FASD is extremely high in many Indigenous communities

and that children who are born with FASD have an increased risk of

coming into adverse contact with the justice system.

- The Committee has heard that Indigenous Australians are far

more likely to experience hearing impairment than non-Indigenous

people. The damage caused by persistent ear disease leaves between

40 percent (urban) and 70 percent (remote) of Indigenous adults

with hearing loss and auditory processing problems.[26] Juveniles with

undiagnosed hearing problems have an increased risk of adverse

contact with the police.

- These health issues that are related to the overrepresentation

of Indigenous juveniles and young adults in the justice system are

examined in detail in chapter 4 of this report.

Education

- Children who have access to a good quality education and who

are supported and directed by their parents to attend school are

likely to develop the necessary knowledge, skills and social norms

for a productive and rewarding adult life.

- The difference in educational attainment between Indigenous and

non-Indigenous Australians is a powerful determinant of the

overrepresentation of Indigenous youth in the justice

system.

- Indigenous children are less likely than non-Indigenous

children to have access to, or participate in early childhood

education. The gap in preschool learning opportunities means that

many Indigenous students will be disadvantaged from their very

first day at school.

- This disadvantage is demonstrated by a substantially lower

proportion of Indigenous students across all year levels achieving

the national minimum standards for literacy and numeracy in 2008,

compared to non-Indigenous students.[27]

- Similarly, year 12 completion rates indicate poor educational

outcomes for Indigenous students. In 2006, the proportion of

Indigenous 19 year olds who had completed year 12 or equivalent (36

percent) was half that of non-Indigenous 19 year olds (74

percent).[28]

- The New South Wales Department of Education and Training

emphasised the link between poor education outcomes and contact

with the justice system, noting that ‘there is a strong

correlation between expulsion from school and incarceration in the

juvenile justice system’[29]. The Department acknowledged that student

outcomes were influenced by a range of factors including:

... other family members' educational experiences and the

capacity of the education system to engage and support students to

develop their individual strengths. Poor nutrition and poor health

status, complex family issues resulting in violence or abuse, poor

housing or overcrowding, poverty and unemployment are all factors

which impact on a student's capacity to engage in and succeed at

learning.[30]

- Chapter 5 of this report examines in detail the need to

increase both school attendance and school achievement in order to

reduce the representation of young Indigenous people in the

criminal justice system.

Employment

- There is a strong relationship between unemployment and

criminal behaviour, particularly when offenders come from low

socioeconomic backgrounds. A study of the 2002 NATSISS found that

nearly 60 percent of Indigenous people who had been charged with an

offence were unemployed.[31]

- In 2006, Indigenous youth aged between 15 and 24 years were

three times more likely than their non-Indigenous counterparts to

be neither employed nor studying. This figure worsened by

remoteness: nearly 40 percent of Indigenous youth in remote areas

aged between 15 and 24 years were neither employed nor studying,

compared with around 25 percent in major cities.[32]

- Chapter 6 of this report examines in detail the evidence

relating to effective transitioning from education to employment,

and measures to secure and retain employment.

Accommodation

- Inadequate accommodation in many Indigenous communities is a

key contributing factor for high rates of juvenile offending. The

2008 NATSISS reported that:

- almost one third of Indigenous children in Australia under the

age of 14 lived in overcrowded accommodation

- in remote areas, this figure increased to 59 percent for

children aged 4 -14 years and 54 percent for children aged 0-3

years

- 39 percent of Indigenous Australians living in remote areas

lived in dwellings that had major structural problems,

and

- 28 percent of Indigenous Australians living in remote areas

lived in dwellings that either lacked or reported problems with

basic household facilities. Basic household facilities considered

important for a healthy living environment include those that

assist in washing people, clothes and bedding; safely removing

waste; and enabling the safe storage and cooking of food.[33]

- The Northern Territory Legal Aid Commission made the following

comments in relation to the impact of inadequate housing on

children's wellbeing and youth justice:

Appropriate safe and affordable housing is the cornerstone for

all other social functioning including health, education and having

children grow up in caring, respectful and thriving communities let

alone building towns, jobs, roads and other infrastructure.

Adequate housing offers safety and security which impacts on social

and physical development, growth and learning.[34]

- High incarceration rates have been linked to youth who have

been in out-of-home care. This is discussed further in chapter 3.

Inadequate accommodation options for Indigenous youth on bail and

after they have been released from detention are discussed in

chapter 7.

Overrepresentation and Closing the Gap

- While primarily the states and territories are responsible for

developing and administering criminal justice policy, a national

approach is required to address the causes of young Indigenous

people coming into contact with the criminal justice system.

Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage is both a national

responsibility and a significant national challenge. It requires an

ongoing commitment and collaboration between all levels of

government working in partnership with Indigenous Australians, the

corporate sector and community organisations. Currently this

national approach is represented by the Council of Australian

Government’s (COAG’s) Closing the Gap program of

generational change.

- Closing the Gap requires governments to address decades of

ineffective investment in services and infrastructure in ways that

are specifically designed to directly benefit Indigenous

Australians. FaHCSIA asserts that:

This agenda is important in both addressing the underlying

causes of much Indigenous juvenile offending and incarceration and

also reducing re-offending and improving life prospects after

initial contact with the justice system.[35]

- Understanding the age profile of Australia’s Indigenous

population is vital to ensure that efforts to overcome Indigenous

disadvantage are directed in the most appropriate way. This profile

is very different to the rest of Australia’s population.

Australia's Indigenous population is growing at twice the rate of

the total Australian population. Indigenous Australians are, on

average, much younger than non-Indigenous people. In 2006 half of

all Indigenous Australians were aged 21 years or younger, while

half of all non-Indigenous Australians were aged 37 or younger.

Children aged less than 15 years comprised 38 percent of the

Indigenous population, compared with 19 percent in the

non-Indigenous population.[36]

- Another challenge facing the Closing the Gap commitment is that

Australia’s Indigenous population is so dispersed

geographically across urban, regional and remote areas. The Prime

Minister’s 2011 report on Closing the Gap stated that:

Almost one third (32 percent) of the Indigenous population live

in major cities. 43 percent of Indigenous Australians live in

regional areas and some 25 percent in remote Australia. In

contrast, 69 percent of non-Indigenous Australians live in major

cities and less than 2 percent in remote and very remote

Australia.

Over half of Indigenous people live in either New South Wales

(30 percent) or Queensland (28 percent). Approximately 14 percent

reside in Western Australia and 12 percent in the Northern

Territory.

Closing the gap will require that policies and programs focus on

both remote areas, where levels of disadvantage are usually higher

and major cities and regional areas where the majority of

Indigenous Australians live, and which also suffer from significant

levels of disadvantage.[37]

- The targets of the COAG commitment to Closing the Gap are

to:

- close the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and

non-Indigenous Australians by 2031

- halve the gap in mortality rates for Indigenous children under

five by 2018

- ensure access to early childhood education for all Indigenous

four year olds in remote communities by 2013

- halve the gap in reading, writing and numeracy achievement for

Indigenous children by 2018

- halve the gap in Year 12 or equivalent attainment rates by

2020, and

- halve the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and

non-Indigenous Australians by 2018.

- These targets are ambitious and serve to focus policy and

government activity over the long term. They are interrelated, with

progress in one area having a positive influence on others.

Ensuring children have a positive start in life and receive a high

quality education means they are less likely to come into contact

with the criminal justice system, and more likely to be employed

and healthy as adults, and are better placed to raise their own

families in the future. For that reason, the Closing the Gap

targets address Indigenous disadvantage both over an

individual’s life cycle and across generations of

people.[38]

- COAG has agreed that these targets will only be achieved

through a sustained commitment towards improving the following

strategic areas or ‘Building Blocks’:

- Early Childhood

- Schooling

- Health

- Economic Participation

- Healthy Homes

- Safe Communities, and

- Governance and Leadership

- FaHCSIA identified that the main elements of this strategy

relevant to reducing juvenile offending are:

- giving children a better start in life through early childhood

education and better schools and better housing. On average,

Indigenous juvenile offenders commit their first crimes at an

earlier age, from ten onwards, than non-Indigenous juveniles,

reflecting disengagement from other options. This earlier start

translates over time into a longer criminal career which leads to a

much greater possibility of incarceration. Reducing overcrowding in

housing, which often creates high levels of stress and inability to

cope with school or other pressures, is a major element of Closing

the Gap

- creating opportunities for parents through improved employment

opportunities and better health outcomes. The consequences of

current life expectancy in Indigenous communities is illustrated by

one study that showed that just under 12 percent of Indigenous

offenders had a parent deceased. Parents debilitated by chronic

disease or having substance abuse issues find it difficult to guide

and manage teenage behaviours, and

- improving delivery of services to Indigenous people that may

help reduce the risk of offending by young people. There is general

recognition that Indigenous people frequently access various

services at a lower level than their needs justify. This can be

because of geographic isolation or cultural or trust issues. COAG

is committed to improving access through the Remote Service

Delivery National Partnership Agreement and the agreed Urban

Regional Service Delivery Strategy.[39]

- Consequently, COAG has agreed to a range of National Frameworks

and National Partnership Agreements, and a National Indigenous Law

and Justice Framework.

- The Prime Minister’s 2011 report on Closing the Gap

announced that some progress is being made, however due to data

limitations and the sheer length of time required to meet specific

targets, it is too early to accurately gauge the success of the

commitment.

- Progress towards the Closing the Gap targets is expected to

lead to improvements in justice outcomes for Indigenous people,

however substantial reductions in Indigenous overrepresentation in

the criminal justice system are only likely to occur in the long

term.

The need for justice targets

- While all of the Building Blocks, and any activity under them,

is relevant to this inquiry, of most relevance is the Safe

Communities Building Block. The Committee finds it striking that

none of the Closing the Gap targets address the Safe Communities

Building Block.

- Wes Morris, from the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture

Centre (KALACC), claimed that the absence of a National Partnership

Agreement linked with the Safe Communities Building Block was an

anomaly in the Closing the Gap strategy which limited the capacity

of governments and non-government organisations to implement

Indigenous justice specific initiatives:

It is almost the perverse irony that most of those building

blocks do have national partnership agreements, but of course one

does not. The one that does not is the safe communities building

block ... it happens to be the one with no national partnership

agreement and thus no funding.[40]

- Emilie Priday from the Australian Human Rights Commission,

called for the inclusion of justice targets in the Closing the Gap

strategy to not only address people entangled in the criminal

justice system, but to increase the likelihood of meeting the

existing targets:

One of the things we have argued for in the last Social Justice

Report is that there should be targets around criminal justice as

well. Obviously targets around criminal justice and reducing

Indigenous imprisonment are going to then support the other targets

that have been set in the Closing the Gap agenda as well.[41]

- Ms Priday expressed her frustration that criminal justice

targets were not incorporated into the broader Closing the Gap

commitment:

At the moment, we have Closing the Gap and a whole heap of

targets in terms of education, health and employment. Yet we do not

have anything around criminal justice targets. When we are looking

at the overrepresentation that we have, it seems crazy that we are

not including that. It is really important for us to put this

forward to the committee as a Closing the Gap issue and also as a

human rights issue.

I guess really what that also means is that then we can have

some sort of platform for integrating some of these issues into

COAG processes. The thing about juvenile justice issues—and I

am sure everyone here has mentioned it and I think we would all

agree—is that they are quite siloed. The beauty of the

Closing the Gap process is that it is bringing together state,

territory and Commonwealth levels of government and

departments—all the different departments. I think that could

be one practical step that we could take in a big picture approach

to where we need to be going in terms of

overrepresentation.[42]

- Similarly, the Australian Children’s Commissioners and

Guardians emphasised that:

... it will be impossible to meet the ‘closing the

gap’ targets around health, education and employment without

also addressing the high level of Indigenous imprisonment which

compounds individual and community disadvantage.[43]

- Katherine Jones from the Attorney-General’s Department,

advised the Committee that work was underway on the development of

justice targets:

... with the intention of including the targets relating to that

in any future COAG reform packages. We are working with the states

and the territories through the Standing Committee of

Attorneys-General Working Group on Indigenous justice to develop

the targets. We hope that the targets will be considered by the

Standing Committee of Attorneys-General at its next meeting on 23

July [2010].[44]

- While the Standing Committee of Attorneys-General (SCAG) is

working on justice targets for possible inclusion in the Closing

the Gap strategy, there is no guarantee that COAG will adopt the

target(s) that SCAG develops. At the time of tabling this report,

the Attorney-General’s Department informed the Committee that

no further developments have been made on Indigenous justice

targets.

- Ms Jones advised the Committee that ‘whilst there [had

been] some negotiations towards a separate National Partnership

Agreement on community safety, there [was] not one being progressed

at the moment’.[45]

- COAG has agreed previously (in May 2009) that the Safe

Communities Building Block, rather than being addressed through a

National Partnership Agreement, would instead be addressed through

three national policy vehicles, including:

- the National Indigenous Law and Justice Framework

2009-2015

- the National Council’s Plan to Reduce Violence against

Women and their Children 2009–2021, and

- the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s

Children

2009–2020.[46]

- These three policy vehicles and a range of state and territory

Aboriginal justice agreements or equivalent strategies will be

discussed in the following section of this chapter.

The National Indigenous Law and Justice Framework

- In November 2009, the Commonwealth and state and territory

governments, through SCAG, endorsed the National Indigenous Law and

Justice Framework (the Indigenous Justice Framework). The

Indigenous Justice Framework represents the first nationally agreed

approach to addressing the issues underpinning adverse contact with

the criminal justice system common to many Indigenous

people.

- The five goals of the Indigenous Justice Framework are:

- improve all Australian justice systems so that they

comprehensively deliver on the justice needs of Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples in a fair and equitable

manner

- reduce over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander offenders, defendants and victims in the criminal justice

system

- ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples feel

safe and are safe within their communities

- increase safety and reduce offending within Indigenous

communities by addressing alcohol and substance abuse,

and

- strengthen Indigenous communities through working in

partnership with government and other stakeholders to achieve

sustained improvements in justice and community safety.[47]

- The Indigenous Justice Framework identifies options for action

that address each of these goals to assist government and

non-government service providers in the development of Indigenous

justice initiatives.

- Commonwealth, state and territory governments are not compelled

to implement any of the Indigenous Justice Framework’s

strategies or actions. Instead, governments can choose what to

implement according to their priorities and resource

capacity.[48]

- The Indigenous Justice Framework includes a Good Practice

Appendix containing a catalogue of good and promising practice

identified by the Commonwealth, state and territory governments. It

is expected that the Appendix will be updated annually to reflect

positive Indigenous justice program developments.

- In August 2009, the Attorney-General, the Hon. Robert

McClelland MP announced a $2 million investment for Indigenous

Justice Program Evaluations.[49] Twenty of the programs identified in the Good

Practice Appendix are being evaluated over two years from December

2010 to December 2012.[50]

- SCAG’s National Indigenous Law and Justice Framework

2009-2015 stated that reports on progress under the Framework will

be provided to SCAG on an annual basis.[51] The

Attorney-General’s Department advised the Committee that no

review of activity under the Framework was undertaken in

2010.[52]

National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their

Children

- In March 2009, an 11-member National Council released the

National Plan for Australia to Reduce Violence against Women and

their Children (the National Plan). The National Plan focuses on

preventative measures to challenge the values and attitudes that

sustain violence in the community. The National Plan emphasises the

need to help people develop respectful relationships that are

non-violent and based on equality and mutual respect.[53]

- The six objectives of the National Plan are:

- communities that are safe and free from violence

- relationships that are respectful

- services that meet the needs of women and their

children

- responses that are just

- perpetrators who stop their violence, and

- systems that work together effectively.[54]

- Although the National Plan recognises that Indigenous women are

more likely to ‘report higher levels of physical violence

during their lifetime ... [and] experience sexual violence and

sustain injury’[55] than non-Indigenous women, it is not an

Indigenous specific plan for action, nor is the issue of violence

against Indigenous women addressed through a single outcome area or

strategy.

- The National Plan is only a set of recommended strategies and

actions, and does not compel the Commonwealth, state or territory

government to implement of any of the suggested

initiatives.

- In April 2009, the Commonwealth Government released its

response to the National Plan, outlining 20 priority actions to

address each of the six outcome areas, only two of which had an

Indigenous specific focus, including:

- an agreement to build on current activities to reduce

overcrowding in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities,

and

- an agreement to consult with States and Territories to develop

national responses to fund healing centres for Indigenous

communities.[56]

National Framework for Protecting Australia’s

Children

- In April 2009, COAG endorsed the National Framework for

Protecting Australia’s Children 2009-2020 (the Child

Protection Framework). The Child Protection Framework seeks to

deliver a more integrated response to the issues affecting the

safety and wellbeing of children.

- The Child Protection Framework does not alter the

responsibilities of governments. State and territory governments

retain responsibility for statutory child protection and the

Commonwealth Government retains responsibility for income support

payments.[57]

- The six supporting outcomes of the Child Protection Framework

are:

- children live in safe and supportive families and

communities

- children and families access adequate support to promote safety

and intervene early

- risk factors for child abuse and neglect are

addressed

- children who have been abused or neglected receive the support

and care they need for their safety and wellbeing

- Indigenous children are supported and safe in their families

and communities, and

- child sexual abuse and exploitation is prevented and survivors

receive adequate support.[58]

- The Child Protection Framework is ‘supported by rolling

three year action plans identifying specific actions,

responsibilities and timeframes for implementation’.[59]

- The Child Protection Framework recognises that Indigenous

children are especially disadvantaged and require additional

responses to the issues they face in terms of their safety and

wellbeing, however it is not an Indigenous specific framework for

action.

State and Territory Indigenous justice agreements

- Aboriginal justice agreements or equivalent strategic documents

exist in New South Wales (New South Wales Aboriginal Justice Plan),

the Australian Capital Territory (ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Justice Agreement), Victoria (Victorian Aboriginal Justice

Agreement), Western Australia (WA State Justice Plan), and

South Australia (Aboriginal Justice Action Plan).

Queensland’s agreement lapsed in 2010 and a draft of the new

agreement has been released for public consultation. These

agreements and documents provide strategic plans, at state and

territory level, to address community safety and rates of

Indigenous offending.

- The Committee noted that Tasmania and the Northern Territory do

not have Aboriginal justice agreements or equivalent strategic

documents.

The Australian Capital Territory

- The ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Agreement

2010-2013 has five goals, which are to:

- improve community safety and improve access to law and justice

service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the

ACT

- reduce the overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander people in the criminal justice system as both victims and

offenders

- improve collaboration between stakeholders to improve justice

outcomes and service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander people

- facilitate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people taking

a leadership role in addressing their community justice concerns,

and

- reduce inequalities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

people in the justice system.

- The agreement was developed by the ACT government in

partnership with the ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Elected Body and the ACT Aboriginal Justice Centre.

- Importantly, the agreement has a reporting framework that is

based on a range of performance measures, including:

- the long term reduction of the number of adults in

custody

- the number of staff undertaking cultural awareness and cultural

competency training with justice agencies

- the number of Indigenous staff employed within key justice

agencies, and

- a range of data sources that include the number of Indigenous

children, young people and adults who come into contact with the

criminal justice system and the nature of that contact.

- The agreement requires:

- annual reporting on performance measures by the relevant ACT

agencies, which may be subject to the ACT Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Elected Body estimate style hearings

- an alignment of territory reporting with national reporting on

work towards the broader Closing the Gap targets, and

- the provision of a public report card on the performance

measures of each agency after two years.[60]

New South Wales

- Until recently New South Wales had an Aboriginal Justice Plan

which set out the following goals:

- reduce the number of Aboriginal people coming into contact with

the criminal justice system

- improve the quality of services, and

- develop safer communities.[61]

- Under the goals were seven strategic direction areas, each with

their respective objectives and actions:

- Aboriginal children

- Aboriginal young people

- community wellbeing

- sustainable economic base

- criminal justice system

- systemic reform, and

- leadership and change.[62]

- However, the New South Wales Aboriginal Justice Advisory

Council no longer exists, with the New South Wales Government now

‘consulting with the network of 20 Aboriginal Community

Justice Groups on law and justice issues affecting Aboriginal

people in NSW’.[63] The Committee was advised that the New South

Wales Department of Aboriginal Affairs are monitoring the

implementation of the New South Wales Aboriginal Justice Plan under

the Two Ways Together process.

Victoria

- The Victorian Aboriginal Justice Agreement Phase 2 (AJA2) has

two aims, which are to:

- minimise Koori over-representation in the criminal justice

system by improving accessibility, utilisation and efficacy of

justice-related programs and services in partnership with the Koori

community, and

- have a Koori community, as part of the broader Victorian

community, that has the same access to human, civil and legal

rights, living free from racism and discrimination and experiencing

the same justice outcomes through the elimination of inequities in

the justice system.[64]

- Under the aims there are six objectives with a range of

strategies and initiatives, including:

- crime prevention and early intervention

- diversion and stronger alternatives to prison

- reduced re-offending

- reduced victimisation

- responsive and inclusive services, and

- stronger community justice responses.[65]

- Andrew Jackomos from the Department of Justice Victoria,

emphasised the issue of partnership between the Victorian

Government, the judiciary, and the Victorian Indigenous community

as fundamental to the success of the AJA2:

What makes our Aboriginal Justice Agreement work – and I

believe it works – is this strong partnership. It is a

dynamic partnership that is regularly tested. But it is a

continuing partnership, and it brings together a government,

judiciary and community ... We have a network of regional

Aboriginal justice advisory committees – I think we now have

nine across the state – that bring together community and

bring together justice agencies at the regional and local level to

identify what the issues are and also to identify locally based

responses.[66]

- The success of the AJA2 is measured by improvements in the

headline indicator which is to reduce the rate of Koori

imprisonment and a large number of intermediary indicators. The

AJA2 acknowledges that:

Because Koori over-representation is heavily influenced by

conditions beyond the control of the justice system, the headline

indicator is unlikely to be sensitive enough to measure decreases

in over-representation caused by AJA2 initiatives. The intermediary

indicators ... are far more able to do this because factors outside

the influence of the AJA2 have less impact on them. Further, they

all contribute to the performance of the headline

indicator.[67]

- The intermediary indicators are worth noting as they reveal how

developed the monitoring framework of the AJA2 is. The intermediary

indicators include:

- number of times Koori youth are processed by police

- proportion of Kooris cautioned when processed by

police

- proportion of Kooris remanded in custody

- proportion of Kooris in maximum security prisons

- proportion of adult Kooris sentenced to prison rather than

other orders

- proportion of Koori youth sentenced to juvenile detention

rather than other orders

- proportion of Koori prisoners released on parole

- proportion of Koori adults/youth who return to prison/juvenile

detention within two years

- proportion of Koori adults/youth who are convicted within two

years of their previous conviction

- proportion of people accessing positive criminal justice

system-related services who are Koori

- number of Kooris employed in criminal justice system-related

agencies

- number of Kooris on intervention orders

- number of Kooris convicted for violent offences against

persons

- number of Kooris who are victims of crime (by offence

category)

- number of Koori volunteers involved in programs

- number of community initiated and implemented programs,

and

- number of Koori organisations delivering programs.[68]

- Mr Jackomos advised the Committee that following the

introduction of the AJA2, there had been sustained improvements in

some of the intermediary indicators:

The response from the Victorian Aboriginal Justice Agreement has

been a reduction in the rate in which young Kooris come into

contact with police, from 75.6 per thousand in 2004-05 down now to

71.6. So our contact is decreasing. There has been an increase in

young Kooris in the 10 to 17 age group cautioned when processed by

police. This is an initiative that the Victorian Aboriginal Legal

Service has led for us in partnership with the Koori communities

and Victoria Police. So that is an increase from 27.9 up to 34. We

see that we are making improvement. There is a huge way to go but

we see that in partnership – and it has to be a strong

partnership – we can make a difference.[69]

Western Australia

- Western Australia’s State Justice Plan (the Justice Plan)

was developed by the State Aboriginal Justice Congress (the State

Congress). It is not a government plan, but sets out some

‘key priorities for negotiation with

Government’.[70] Those key priorities are:

- reform the criminal justice system to achieve fair treatment

for Aboriginal people

- tackle alcohol, drug abuse and mental health issues

contributing to crime, and

- strengthen families and communities to build identity and help

prevent violence and other crime.[71]

- Under each of these priority areas, the State Congress will

seek to negotiate specific agreements with State and Commonwealth

government agencies, drawing upon identified strategies and actions

under each of the priority areas.[72]

- Leza Radcliffe from the State Congress, told the Committee that

the strength of the Justice Plan was that it drew on the voices of

Aboriginal people:

This is one of the better true representations of the Aboriginal

voice with regard to justice issues ... We access a lot of people

at a regional level and a local level because the issues are

current and relevant to people. In our different areas we have come

up with our strategies for our region and they have been combined

in that one document. That is a good representation of what we hope

to achieve at a state level.[73]

- Review and evaluation of the Justice Plan is expected to occur

at two levels. The first focuses on the individual agreements

negotiated with State and Commonwealth government agencies, while

the second looks at the Justice Plan as a whole. Review of the

individual agreements will occur annually, while the review of the

Justice Plan will occur either in 2011 or 2012.[74]

South Australia

- South Australia’s Aboriginal Justice Action Plan 2008-14

(the Action Plan) has five goals, including:

- to ensure all South Australians have access to democratic, fair

and just services

- to ensure that crime is dealt with effectively

- to improve public safety through education, prevention and

management

- to contribute towards building sustainable communities,

and

- to excel in service delivery innovation and government

efficiency.[75]

- The priority actions in the plan are drawn from implementation

plans from South Australia’s Strategic Plan targets.[76] Each priority action is

supported by a lead agency, and identifies key performance

indicators, timeframes for action, and contributing agencies.

Queensland

- A draft of the new Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Justice Strategy has been released for public consultation

(closing 30 May 2011). The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Justice Strategy 2011-2014 is a three year program that aims to

reduce Indigenous offending and re-offending in

Queensland.

- The key features of the strategy are:

- a place-based approach, focusing on select locations in urban,

regional and remote Queensland (these include Cairns, Townsville,

Mount Isa, Rockhampton and Brisbane and discrete Aboriginal

communities and the Torres Strait Islands)

- an ongoing assessment of Indigenous justice (and

justice-related) programs and services, in consultation with

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and other key

stakeholders

- an annual report to Parliament on progress

- actions which link with the government’s work relating to

the Crime and Misconduct Commission report, Restoring Order: Crime

prevention, policing and local justice in Queensland’s

Indigenous communities, including:

- the commitment to review the Community Justice Group program,

local law and order laws, and the use of local Indigenous people in

policing roles

- consistency with the national approach to Indigenous justice

and community safety issues agreed under the National Indigenous

Law and Justice Framework, and

- a program of action to make on-the-ground changes that will

reduce over-representation and improve community safety for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.[77]

- A Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice

Taskforce will be established to monitor the implementation,

direction and progress of the Strategy. The Taskforce will:

... be chaired by an Indigenous community leader and include

representatives from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

communities (including a representative from Queensland Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Council (QATSIAC) and from

community justice groups), State and local governments (including

Directors-General of key State Government agencies), the community

sector and the private sector.[78]

- The Strategy has been devised to reduce the statistical

overrepresentation of Indigenous people in the criminal justice

system. It has more immediate targets to be achieved within three

years, including a commitment to ensure that:

100 high-risk Indigenous young people, including those who have

had contact with the Youth Justice system, will be transitioned to

employment after receiving a qualification, mentoring and other

assistance in the building of the recreational Active Trail between

Kingaroy and Theebine (132 km).[79]

- The Strategy aims to put in place policy measures that will

improve outcomes in the longer term to increase early intervention

and prevention support, and to improve the treatment and

rehabilitation of offenders. These long term targets include

ensuring that:

- all parents or carers of young Indigenous people who come into

contact with the youth justice and child safety systems will be

offered parenting and/or family support

- all Indigenous people in prison or detention who are in need of

literacy and numeracy training will receive it, including those on

short stays (i.e. less than 12 months), and

- all prisons and detention centres will provide driver education

support to assist people to get their licence, or to regain it,

including those on short stays (i.e. less than 12 months).[80]

Committee comment

- The Committee was disturbed to hear that not only do Indigenous

juveniles and young adults continue to be overrepresented in

detention centres and prisons, but that levels of incarceration are

increasing despite ongoing effort and funding in this area. It is

shameful that in 2011 Indigenous people are more likely to be

detained or imprisoned than at any other time since the 1991 Royal

Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody report.

- The Committee is concerned deeply that Indigenous people,

especially Indigenous women, are at such a high risk of being the

victims of violent crime.

- The Committee recognises that the overrepresentation of

Indigenous juveniles and young adults in the criminal justice

system is a consequence of the chronic disadvantage experienced by

many Indigenous communities.

- The Committee acknowledges the need to provide for and support

safe and healthy communities that empower Indigenous youth and

their families to be strong and self-determining, and to equip

young Indigenous people with a positive sense of identity,

educational attainment and the appropriate life skills to make

positive choices for their future. The Committee recognises the

critical need for early intervention to nurture the next generation

of young Indigenous people and prevent them from coming into

adverse contact with the criminal justice system.

- The Committee notes that the majority of states and territories

have Indigenous justice agreements or equivalent strategic

documents in place - the exceptions are Tasmania and the Northern

Territory. The Committee notes the importance of such agreements

and the need for each state and territory to shape agreements

appropriate to the issues and communities in their

jurisdiction.

- While supportive of the variations this will bring to each

agreement, the Committee considers there is a need for some states

and territories to provide greater detail in their agreements and

to ensure appropriate Indigenous involvement in the design and

implementation of the agreement.

- The Committee considers that such agreements should be viewed

as dynamic and elements should be reviewed regularly and updated

following monitoring and evaluation of area outcomes. Victoria and

Western Australia appear to have a sound Indigenous partnership

approach and Victoria has a well developed system of monitoring.

The Committee is encouraged by Queensland’s draft strategy

approach to including Indigenous representation in its

implementation and monitoring framework.

- The Committee urges other states and territories to re-evaluate

their own agreements and be willing to build on the work of others.

In particular, the Committee urges Tasmania and the Northern

Territory to develop appropriate justice agreements in partnership

with their Indigenous communities.

- The Committee is supportive of COAG’s Closing the Gap

strategy. The existing Closing the Gap targets and the National

Partnership Agreements that focus activity on the Building Blocks

provide a sound foundation for addressing Indigenous

disadvantage.

- While the Closing the Gap strategy, in the Committee’s

view, establishes a sound foundation for addressing Indigenous

disadvantage, the Committee is concerned about both the lack of

activity under the Safe Communities Building Block and the absence

of an Indigenous justice target to complement the existing targets

in the areas of health, education and employment.

- The Committee commends Commonwealth and state and territory

governments on the development and endorsement of the National

Indigenous Law and Justice Framework. Insofar as it provides

stakeholders with a coherent strategy for pursuing improvements in

justice outcomes for Indigenous people, it is a comprehensive

document of value to those who choose to use it in this

manner.

- The Committee is encouraged by the development of the National

Plan for Reducing Violence against Women and their Children. The

actions in the National Plan that specifically address Indigenous

women and children are well considered, and likely to lead to

improvements in safety, if implemented.

- The Committee commends COAG on the endorsement of the National

Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children. It is pleasing

to see that the issue of Indigenous community safety is being

addressed in a specific outcome area.

- However, the Committee has some concerns with aspects of the

National Indigenous Law and Justice Framework, the National Plan to

Reduce Violence against Women and their Children, and the National

Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children.

- Foremost amongst those concerns is that the National Indigenous

Law and Justice Framework, while comprehensive in its

identification of Indigenous justice issues, does not compel any

jurisdiction to implement its strategies and actions, and is

unlikely to lead to any coordinated and sustained activity in this

area.

- Neither the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and

their Children nor the National Framework for Protecting

Australia’s Children is Indigenous specific. Where Indigenous

issues do receive focused attention, as they do in the National

Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children, that attention

is restricted to issues relating to Indigenous community safety

rather than the full spectrum of issues affecting Indigenous

people’s contact with the criminal justice system.

- The Committee does not accept that the Safe Communities

Building Block is being well served by these three policy vehicles

as suggested by COAG.

- The Committee is of the view that Closing the Gap in the

identified target areas between Indigenous and non-Indigenous

people can only be achieved if the Safe Communities Building Block

is addressed in a nationally coordinated and sustained manner with

attention focused not only on Indigenous prevention and diversion,

but also on rehabilitation.

- The Committee does not accept the view that investment in

education, health, housing and employment initiatives are

sufficient to close the gap in Indigenous justice outcomes.

Certainly, initiatives in these areas will have a positive impact

on Indigenous imprisonment rates in the long term. However, the

idea that initiatives in these areas are all that are needed to be

successful fails to recognise intergenerational patterns in which a

significant number of Indigenous people are entangled already

within the criminal justice system. These people return to their

communities upon release, often without improved prospects and with

the capacity to negatively influence others in their

communities.

- Therefore, the Committee considers that the most effective

means of focusing activity on the Safe Communities Building Block

and for supporting activity under the other Building Blocks is

through the development of a National Partnership Agreement

dedicated to improving Indigenous justice and community safety

outcomes.

- Although the Commonwealth Government and state and territory

governments will be responsible for developing the details of the

National Partnership Agreement, the Committee considers it

necessary that prevention, diversion and rehabilitation are equally

addressed as part of that agreement.

- The Committee considers it vital that justice targets are

included in the COAG Closing the Gap strategy. The Committee

recommends that the Commonwealth endorse the justice targets

developed by SCAG and strongly urges all states and territories to

support the inclusion of a Safe Communities Building Block related

Partnership Agreement and justice targets in the Closing the Gap

strategy.

Recommendation - National Partnership Agreement

|

-

|

The Committee recommends that the Commonwealth

Government develop a National Partnership Agreement dedicated to

the Safe Communities Building Block and present this to the Council

of Australian Governments by December 2011 for inclusion in the

Closing the Gap strategy.

|

Recommendation - Justice targets

|

-

|

The Committee recommends that the Commonwealth

Government endorse justice targets developed by the Standing

Committee of Attorneys-General for inclusion in the Council of

Australian Governments’ Closing the Gap strategy. These

targets should then be monitored and reported against.

|

[1] Australian

Institute of Criminology (AIC), ‘Juvenile detention’,

30 June 2007,

<www.aic.gov.au/statistics/criminaljustice/juveniles_detention.aspx>

accessed 24 February 2011.

[2] Australian

Bureau of Statistics (ABS), National Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Social Survey 2008, Canberra.

[3] Figures derived

from total Indigenous prisoner numbers by sex in 2000 and 2010. ABS

2000, Prisoners in Australia 4517.0, Canberra, p.11; ABS 2010,

Prisoners in Australia 4517.0, Canberra, p. 52.

[4] ABS 2009,

Prisoners in Australia 4517.0, Canberra.

[5] Age

standardisation is a statistical method used by the ABS that

adjusts crude rates to account for age differences between study

populations. For more information, see the explanatory notes,

paragraphs 34-39, at <www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/

Lookup/4517.0Explanatory%20Notes12010?OpenDocument> accessed 11

May 2011.

[6] ABS 2009,

Prisoners in Australia 4517.0, Canberra.

[7] ABS 2009,

National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2008,

Canberra.

[8] AIC, submission

67, p. 2.

[9] AIC 2007,

Juveniles’ contact with the criminal justice system in

Australia. AIC, Canberra p. 1.

[10] Communiqu ,

Indigenous Community Safety Roundtable, Sydney, 6 November

2009.

[11] ABS, Recorded

Crime – Victims, Cat. No. 4510.0, June 2010, pp. 38-9.

[12] Jacqueline

Fitzgerald & Don Weatherburn, ‘Aboriginal Victimisation

and Offending: The Picture from Police Records’, Crime and

Justice Statistics Bureau Brief, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and

Research (BOCSAR), December 2001, p. 2.

[13] Steering

Committee for Review of Government Services (2009), Overcoming

Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2009 – Report, p.

4.131.

[14] D

Weatherburn, L Snowball & B Hunter, The economic and social

factors underpinning Indigenous contact with the justice system:

Results from the 2002 NATSISS survey. Crime and Justice Bulletin,

No. 24.

[15] Commonwealth

of Australia, Royal Commission into Deaths in Custody, 1991, Vol.

1, p. 1.7.1.

[16] Department of

Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

(FaHCSIA), submission 79, p. 3.

[17] Courts

Administration Authority (CAA), submission 69, p. 9.

[18] Kimberley

Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre (KALACC), exhibit 5, p. 6.

[19] SCRGSP,

Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2009 Report, p.

7.1.

[20] Substance

misuse refers to a range of harmful activities including petrol

sniffing and chroming (inhaling a range of chemical products to

produce a high feeling).

[21] Royal

Australasian College of Physicians, submission 53, p. 5.

[22] Royal

Australasian College of Physicians, submission 53, p. 5.

[23] J Howard,

& E Zibert, 1990, ‘Curious, bored and waiting to feel

good: the drug use of detained young offenders’, Drug and

Alcohol Review, no. 9, pp. 225-31.

[24] J Hando, J

Howard & E Zibert, 1997, ‘Risky drug practices and

treatment needs of youth detained in New South Wales Juvenile

Justice Centres’, Drug and Alcohol Review, vol 16, no. 2, pp.

137-45.

[25] D

Weatherburn, L Snowball, & B Hunter, ‘The economic and

social factors underpinning Indigenous contact with the justice

system: Results from the 2002 NATSISS survey’, Crime and

Justice Bulletin, no. 24.

[26] Damien

Howard, submission 87, p. 5.

[27] Steering

Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision,

Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2009 Report, p.

4.3.2.

[28] Steering

Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision,

Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2009 Report, p.

4.5.0.

[29] New South

Wales Department of Education and Training, submission 43, p.

2.

[30] New South

Wales Department of Education and Training (NSWDET), submission 43,

p. 2.

[31] D

Weatherburn, L Snowball, & B Hunter, ‘The economic and

social factors underpinning Indigenous contact with the justice

system: Results from the 2002 NATSISS survey’, Crime and

Justice Bulletin, no. 24.

[32] SCRGSP

Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2009 Report, p.

6.32.

[33] ABS 2009,

National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2008,

Canberra.

[34] Northern

Territory Legal Aid Commission (NTLAC), submission 45, p. 3.

[35] FaHCSIA,

submission 79, p. 7.

[36] Closing the

Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2011, p. 10.

[37] Closing the

Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2011, p. 11.

[38] Closing the

Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2011, p. 9.

[39] FaHCSIA,

submission 79, p. 8.

[40] Wes Morris,

KALACC, Committee Hansard, Perth, 30 March 2010, p. 60.

[41] Emilie

Priday, Australian Human Rights Commission, Committee Hansard,

Sydney, 4 March 2010, p. 31.

[42] Emilie

Priday, Human Rights Commission, Committee Hansard, Sydney, 28

January 2011, p. 80.

[43] Australian

Children’s Commissioners and Guardians, submission 59, p.

5.

[44] Katherine

Jones, Attorney-General’s Department, Committee Hansard,

Canberra, 27 May 2010, p. 2.

[45] Katherine

Jones, Attorney-General’s Department, Committee Hansard,

Canberra, 27 May 2010, p. 21.

[46] SCAG,

National Indigenous Law and Justice Framework 2009-2015, p. 6.

[47] SCAG,

National Indigenous Law and Justice Framework 2009-2015, p. 10.

[48] SCAG,

National Indigenous Law and Justice Framework 2009-2015, p. 4.

[49] Hon. Robert

McClelland MP, ‘Indigenous Young People Crime and Justice

Conference’, August 2009, p. 8.

[50]

Attorney-General’s Department, Evaluation of Indigenous

justice programs in support of the National Indigenous Law and

Justice Framework,

<www.ema.gov.au/www/agd/agd.nsf/Page/Indigenous_law_and_native_titleIndigetitl_law_programs>

accessed 5 May 2011.

[51] SCAG,

National Indigenous Law and Justice Framework 2009-2015, p. 31.

[52] The advice

was received from the Attorney-General’s Department on 28

April 2011.

[53] National

Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children, Time

for Action: The National Council’s Plan to Reduce Violence

Against Women and their Children, 2009-2021, March 2009, p. iv.

[54] National

Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children, Time

for Action: The National Council’s Plan to Reduce Violence

Against Women and their Children, 2009-2021, March 2009, pp.

16-20.

[55] National

Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children, Time

for Action: The National Council’s Plan to Reduce Violence

Against Women and their Children, 2009-2021, March 2009, p. 9.

[56] Commonwealth

of Australia, The National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women,

Immediate Government Actions, April 2009, p. 15.

[57] Commonwealth

of Australia, National Framework for Protecting Australia’s

Children 2009-2020, p. 9.

[58] Commonwealth

of Australia, National Framework for Protecting Australia’s

Children 2009-2020, p. 11.

[59] Commonwealth

of Australia, National Framework for Protecting Australia’s

Children 2009-2020, p. 5.

[60] ACT

Government and ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elected

Body, ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Agreement

2010-2013, p.23.

[61] NSW

Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council, NSW Aboriginal Justice Plan:

Beyond Justice

2004-2014, p. 8.

[62] NSW

Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council, NSW Aboriginal Justice Plan:

Beyond Justice

2004-2014, p. 10.

[63] New South

Wales Government, Crime Prevention Division,

<www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/ajac> accessed 13 July 2010.

[64] Victorian

Government, Victorian Aboriginal Justice Agreement Phase 2, 2006,

p. 19.

[65] Victorian

Government, Victorian Aboriginal Justice Agreement Phase 2, 2006,

p. 20.

[66] Andrew

Jackomos, Department of Justice, Victoria, Committee Hansard,

Melbourne,

3 March 2010, p. 22.

[67] Victorian

Government, Victorian Aboriginal Justice Agreement Phase 2, 2006,

p. 26.

[68] Victorian

Government, Victorian Aboriginal Justice Agreement Phase 2, 2006,

pp. 26-27.

[69] Andrew

Jackomos, Committee Hansard, Melbourne, 3 March 2010, p. 22.

[70] Government of

Western Australia, State Justice Plan 2009-2014, p. 7.

[71] Government of

Western Australia, State Justice Plan 2009-2014, p. 8.

[72] Government of

Western Australia, State Justice Plan 2009-2014, p. 8.

[73] Leza

Radcliffe, State Aboriginal Justice Congress, Committee Hansard,

Perth, 30 March 2010,

p. 55.

[74] Government of

Western Australia, State Justice Plan 2009-2014, 2009, p. 9.

[75] Government of

South Australia, Aboriginal Justice Action Plan, 2009, p. 3.

[76] Government of

South Australia, Aboriginal Justice Action Plan, 2009, p. 2.

[77] Government of

Queensland, Draft Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice

Strategy 2011-2014 Summary, p. 1.

[78] Government of

Queensland, Draft Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice

Strategy 2011-2014, p. 27.

[79] Government of

Queensland, Draft Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice

Strategy 2011-2014, p. 29.

[80] Government of

Queensland, Draft Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice

Strategy 2011-2014, p. 29.

Navigation: Previous

Page | Contents | Next Page

Back to top