Key points

- The Bill proposes amendments to Commonwealth whistleblower protection law.

- Specifically it intends to improve the regime applying to those public officers of Commonwealth agencies who make public interest disclosures regarding wrongdoing or ‘disclosable conduct’.

- These reforms to the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 (PID Act) are a response to the Moss Review of 2016.

- A major change is the proposal to narrow the definition of ‘disclosable conduct’. This would remove disclosures relating to ‘personal work-related conduct’ from the scope of disclosable conduct (and thus protection of the PID Act). These matters would be addressed under alternative frameworks.

- The Bill would insert a positive duty to protect whistleblowers upon principal officers of Commonwealth agencies.

- A second round of reforms to the PID Act later in 2023 has been pledged by the Attorney‑General.

- The Bill does not create a Whistleblower Protection Authority. However, the Attorney-General has stated that consultations on that issue will commence shortly.

Introductory Info

Date introduced: 30 November 2022

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Attorney-General

Commencement: Schedules 1 to 3 commence on the earlier of Proclamation or 6 months after Royal Assent.

The commencement of Schedule 4 is contingent upon the commencement of section 40 of the National Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2022 and Schedule 1 to the National Anti-Corruption Commission (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Act 2022.

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose

- The

Bill amends the Commonwealth public sector whistleblower protection regime.

- The

current Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 permits a selected range of public

interest disclosures by persons who are ‘public officials’ or former public

officials in the Commonwealth public sector, regarding suspected wrongdoing (‘disclosable

conduct’) by another public official or Commonwealth agency. The Act requires

agencies to investigate disclosures. If disclosures fall within the protection

regime of the Act, the whistleblower has certain legal protections against

reprisal actions and immunity from civil, criminal and administrative liability.

- The

Bill proposes the first of two tranches of reforms to the PID Act,

promised by the incoming Government, as a response to Moss Review of the

Act, published in 2016.

- The Bill implements 21 of the 33 recommendations of the Moss

Review, in addition to recommendations from two other Inquiries (in 2017 and

2019–20).

- The first major change is to remove disclosures relating to

personal work-related disputes and conduct from the scope of ‘disclosable

conduct’ under the PID Act.

- The

second inserts a positive duty to support PID disclosers and witnesses, upon

principal officers of Commonwealth agencies.

- Related are reforms to enable greater information-sharing, removing

a general secrecy offence and facilitating agencies to appropriately share

information relating to a disclosure to enable it to be investigated by the

most suitable agency.

- Additional reforms are proposed to increase and improve the role

of the Commonwealth Ombudsman and the IGIS in having oversight of the handling

of PID disclosures.

- A second tranche of changes to the PID Act is promised by

the Attorney-General.

Key Issues

- A key change is to remove disclosures relating solely to personal

work-related disputes and conduct from the scope of ‘disclosable conduct’. The

drafting is convoluted and involves three exclusions from an exemption.

- Proposals around exclusion of work-related disputes from the PID

Act have been critiqued on the basis that they go beyond the Moss

Review recommendations.

- Other criticism has flowed from the fact that this Bill does not

propose a National Whistleblower Protection Authority or Commissioner. The

Government has promised to open a round of public consultation on that

question.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Public

Interest Disclosure Amendment (Review) Bill 2022 (the Bill) is to make changes

to the legislative framework for the Commonwealth public sector whistleblower

protection scheme in response to review recommendations.

The Bill proposes amendments to the Public Interest

Disclosure Act 2013 (the PID Act) and related (contingent) amendments

to the National

Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2022 (NACC Act).

The broad rationale is to support the Government’s law

reform agenda in public administration, and its focus on integrity. The

amendments to the PID Act are also linked to recent anti-corruption enactments.

As the Attorney-General explained when introducing the Bill in November 2022: ‘an

effective public sector whistleblowing framework is essential to … support

disclosures of corrupt conduct to the National Anti-Corruption Commission

[NACC]’.[1]

The National

Anti-Corruption Commission (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Act 2022

(NACC Consequential Act)—which

received Royal Assent in December 2022—will make amendments to the PID Act

(relating to the inter-relationship of anti-corruption investigations and public

interest disclosure (PID) investigations).[2] This Bill proposes a further

round of amendments to the PID Act to provide additional protections to

whistleblowers, and to simplify administration for Commonwealth agencies regarding

PID matters.

The Bill proposes the first of two tranches of reforms to

the PID Act, promised by the incoming Government, to implement selected recommendations

of the first statutory review of the Act, by Philip Moss AM (the Moss

Review), tabled in

Parliament in October 2016.

As the Moss Review explained:

The PID Act is intended to bring forth and investigate

disclosures of serious wrongdoing within agencies, to ensure they are

investigated, to enable agencies to fathom the nature of this wrongdoing, and

to address it. Disclosures made under the PID Act shine a light on

wrongdoing: these disclosures help agencies understand and tackle pockets of

wrongdoing and the culture enabling it.[3]

Public

interest disclosures (whistleblowing)

Public interest disclosure, otherwise known as ‘whistleblowing’,

can be defined as a ‘disclosure by organisation members (former or current) of

illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices under the control of their

employers, to persons or organisations that may be able to effect action’.[4]

It is argued that whistleblowers are important ‘because

they can promote an informed society and provide an essential and valuable

service to the public by exposing wrongdoing’.[5]

Among the most famous whistleblower cases internationally is that of Daniel

Ellsberg who leaked the ‘Pentagon

Papers’, an act that arguably contributed to a more rapid end to the

Vietnam War.[6]

Technology has opened opportunities for anonymous external

whistleblowing, with some newspapers offering source anonymity for

whistleblowers to communicate with journalists.[7]

Purpose:

Implementation of Recommended Reforms

The Government advises that the Bill will implement:

Additional

future amendments

It is understood that the Government intends whistleblower

protection law reform to be rolled out in two tranches (or stages).

The Attorney-General has stated that the reforms would aim

to simplify the PID scheme and improve protections for public sector

whistleblowers to make them more ‘effective and accessible’.[10]

In November 2022, he explained that this Bill containing the first tranche of

reforms was designed to:

ensure immediate improvements to the public sector

whistleblower scheme are in place before the [National Anti-Corruption

Commission] NACC commences in mid-2023.[11]

The second tranche of reforms is envisaged to be presented

after passage of the present Bill and in the words of the Attorney, will involve

‘redrafting the … Act to address the underlying complexity of the scheme’.[12] The Attorney has undertaken

to consult with the public during 2023 on these reforms and to issue ‘a

discussion paper on whether there is a need to establish a Whistleblower

Protection Authority or Commissioner’.[13]

Structure

of the Bill

The Bill amends the PID Act and the NACC Act.

The Bill has four Schedules that make amendments as

follows:

Schedule 1, which has seven Parts:

- Part

1 amends the PID Act to remove protection for disclosure of

information that concerns ‘personal work-related conduct’ from the

whistleblower protection legislation.

- Part

2 makes amendments relating to the handling, allocation and investigation

of disclosures in situations such as where another agency is better able to

handle a disclosure, or where other law or power would be more appropriate for

an investigation of the disclosure.

- Part

3 makes a number of amendments relating to reprisals against whistleblowers

and witnesses, by extending protections to witnesses and also by extending the

definition of reprisals.

- Part

4 would make amendments to facilitate the reporting and sharing of information,

principally by repealing the general secrecy offence.

- Part

5 proposes amendments to clarify the roles of the Ombudsman and the IGIS in

relation to complaints about an agency’s handling of a protected disclosure

(PID).

- Part

6 would provide for the handling and transfer of disclosures from one

agency to another after there has been a machinery of government (MOG) change,

in other words, after functions are transferred from one Commonwealth agency to

another.

- Part

7 would amend the definitions of ‘agencies’, ‘public officials’ and

‘principal officers’ to include reference to Commonwealth entities and to

clarify that judicial officers, members of Parliament and their staff are not

public officials.

Schedule 2 of the Bill makes additional minor

amendments to the PID Act including updating the section giving an

outline of the legislation, and other amendments aimed at consistency. It would

also provide for a further review of the Act to be completed 5 years after these

amendments commence.

Schedule 3 clarifies how amendments proposed in

Schedules 1 and 2 would apply.

Schedule 4 amends the National Anti-Corruption (NACC)

legislation and the PID Act to support the operation of the NACC. The

amendments aim to ensure consistency of protection for disclosures across the

anti-corruption and whistleblower protection laws.

Background

By 2013, the Commonwealth was the only Australian

jurisdiction that did not have legislation dedicated to facilitating public

interest disclosures and protecting whistleblowers, with the states and territories

having already enacted such laws in advance of the Commonwealth.[14]

Prior to 2013, there were numerous unsuccessful prior attempts, in private

members Bills, to introduce comprehensive Commonwealth whistleblower protection

laws.[15]

The Public

Interest Disclosure Bill 2013 (PID Bill) was introduced by Mark Dreyfus during

his first term as Attorney-General. (Further detail on the PID Bill is

available in several Library publications).[16]

The PID Bill passed both houses on 26 June 2013,[17]

with an expressed aim of establishing ’a single comprehensive scheme to support

inquiry into wrongdoing in the Commonwealth public sector and those who report

it’.[18]

The PID Bill was criticised by the Greens and Andrew Wilkie.

Mr Wilkie stated that the Government Bill:

weaves a web of extraordinarily complicated definitions to

negatively frame the circumstances in which public interest disclosures are

protected.[19]

Senator Milne of the Australian Greens expressed the view

that:

This proposed legislation essentially sets up trip wires at

every turn and one wrong step means the whistleblower is out on their own,

exposed to lengthy and stressful legal retribution … Whistleblower protection

must encourage those hesitant about speaking out, but there are so many

specific requirements for a disclosure in this bill that I fear it will do the

opposite …[20]

Outline of the PID Act

This section provides the reader with a recap of the present

PID Act, which has been in force for nearly a decade. A useful outline

of the PID Act is set out in a factsheet and flowchart, prepared by the

Commonwealth Ombudsman.[21]

A more detailed yet ‘plain English’ explanation of the PID Act is

provided by the Ombudsman’s publication Agency

Guide to the PID Act: Version 2, April 2016.

Objects

The objects of

the PID Act are:

(a) to promote the integrity and

accountability of the Commonwealth public sector; and

(b) to encourage and facilitate the

making of public interest disclosures by public officials; and

(c) to ensure that public officials who

make public interest disclosures are supported and are protected from adverse

consequences relating to the disclosures; and

(d) to ensure that disclosures by public

officials are properly investigated and dealt with.[22]

Application

The PID Act is a framework applying to the reporting

of wrongdoing by public officials in the Commonwealth public sector. The Act

states that it ‘provides a means for protecting public officials, and former

public officials, from adverse consequences of disclosing information that, in

the public interest, should be disclosed’.[23]

The Act operates in parallel with Commonwealth law for

whistleblower protection in the private sector in the Corporations Act.[24]

The PID Act only applies to the APS employees and

other ‘public officials’ of the Commonwealth public sector (section 69).

In broad terms, the PID Act

provides for:

• qualified

protection of disclosers

• investigation

of disclosures when made internally

• administration

of protected disclosure investigations.

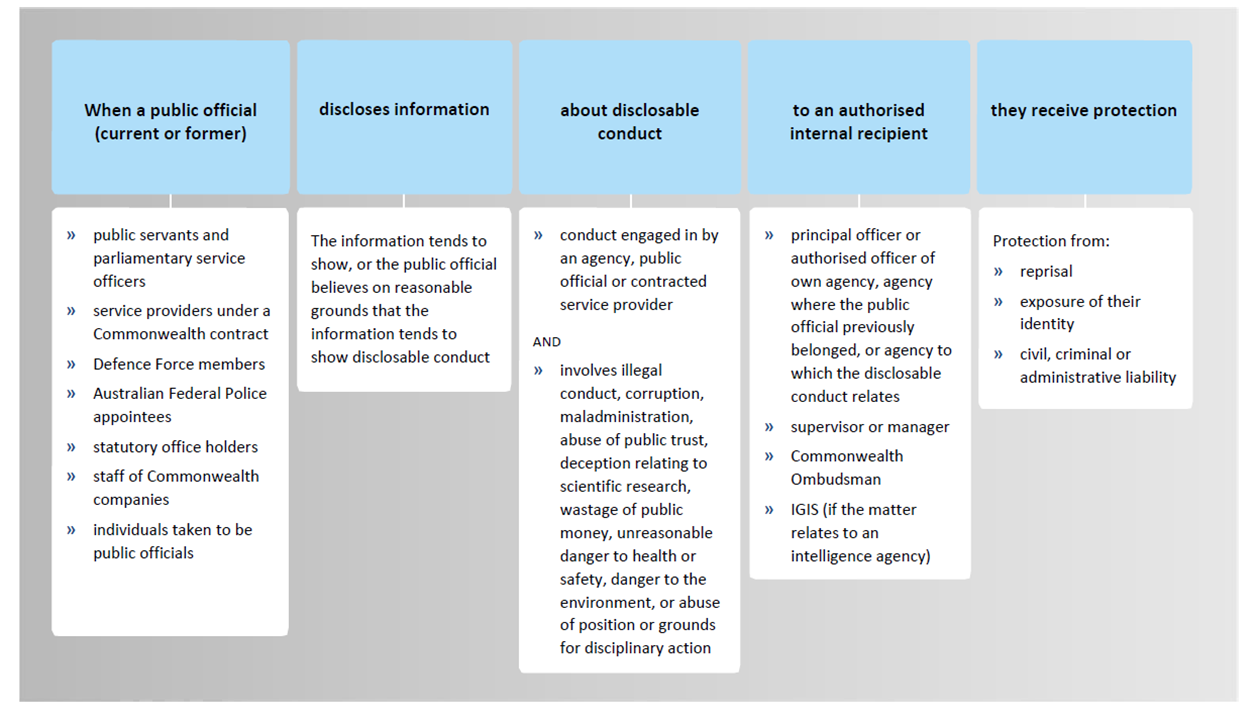

Figure 1: Simplified outline of an internal public interest disclosure (Ombudsman: 2016:3)

Source: 2021–2022 Annual Report, Commonwealth Ombudsman, 36.

The Act requires Commonwealth agencies to investigate and respond to disclosures

that meet the test of being ‘public interest disclosures’. It provides

protections to public officials who make qualifying disclosures.

The protection of external disclosures is also subject to

a requirement that they be ‘on balance, not contrary to the public interest’.[25]

Agencies subject to the Act

The Act applies to Departments, Executive Agencies and

prescribed authorities.[26]

According to the Commonwealth Ombudsman there are 176 agencies subject to the PID

Act.[27]

Four categories of disclosure

The PID Act protects four types of ‘public interest

disclosure’ (PID), namely:

- internal

disclosures

- external

disclosures

- emergency

disclosures, and

- legal

practitioner disclosures.[28]

As explained in the Act:

Broadly speaking, a public interest disclosure is a

disclosure of information, by a public official, that is:

-

a disclosure within the

government, to an authorised internal recipient or a supervisor, concerning

suspected or probable illegal conduct or other wrongdoing (referred to as

“disclosable conduct”); or

-

a disclosure to anybody, if an

internal disclosure of the information has not been adequately dealt with, and

if wider disclosure satisfies public interest requirements; or

-

a disclosure to anybody if there

is substantial and imminent danger to health or safety; or

-

a disclosure to an Australian

legal practitioner for purposes connected with the above matters.

However, there are limitations to take into account the need

to protect intelligence information.[29]

Who can

disclose: a Public Official

Only those defined as a ‘public official’ may make public

interest disclosures under the Act.[30]

The definition is also relevant to the persons whose conduct can be the subject

of a public interest disclosure.

Public official is defined in section 69 of

the PID Act and includes:

- an APS employee, or Secretary in, a

Department

- an APS employee in, or Head of, an

Executive Agency

- a principal officer of, or member of the

staff of, or an individual who constitutes, a prescribed authority[31]

- a member of a prescribed authority (other

than a court)

- a director of a Commonwealth company

- a member of the Defence Force

- an Australian Federal Police appointee

- a Parliamentary service employee (within

the meaning of the Parliamentary Service Act 1999)

- an individual who is employed by the

Commonwealth otherwise than as an APS employee and who performs duties for a

Department, an Executive Agency or prescribed authority

- certain statutory officeholders.[32]

Contractors

Can a

contractor use the Commonwealth whistleblower law? The answer is that this

depends on them meeting several legislative tests. These are firstly to be a

‘public official’, and secondly, to be disclosing ‘disclosable conduct’.

In specified

circumstances, contractors fall within the definition of ‘public official’ for

the purposes of the PID Act. This is if they are:

- an individual who is a contracted service

provider for a Commonwealth contract, or

- an officer or employee of a contracted

service provider for a Commonwealth contract and who provides services for the

purposes of the Commonwealth contract.[33]

The

application of the PID Act to contractors also depends on the definition

of disclosable conduct, which includes conduct ‘engaged in by a

contracted service provider for a Commonwealth contract, in connection with

entering into, or giving effect to, that contract’.[34]

Internal

disclosure

The main route for disclosures provided by the PID Act

is ‘internal disclosures’ within government which are made to ‘authorised

internal recipients’.[35]

Whistleblowers can also disclose directly to their supervisors.[36]

Further, disclosures can also be considered to be internal

disclosures, when made outside of an agency, if made to the Commonwealth

Ombudsman, the Inspector General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS).[37]

(This Digest explains the roles of the Ombudsman and IGIS in more detail below).Despite

perceptions of the general public that whistleblowers take their concerns to

the media, the emphasis of the PID Act is on internal, rather than

external disclosure, at least in the first instance. As summarised by the Moss

Review: ‘External public interest disclosures can be made in a narrow range

of circumstances and usually only after an internal disclosure has been made’.[38]

The Bills Digest on the PID Bill 2013 explained: Internal disclosures are

central to the PID scheme as there is an underlying assumption in the Bill that

public interest disclosures should be ‘internal’ unless there is sufficient

justification for the disclosure to be ‘external’.[39]

Three

preconditions for a valid internal disclosure

To make a valid internal PID, and thus receive the

protections and immunities under the PID Act, a person disclosing

suspected wrongdoing must:

1. be a current or former public official

2. make

their disclosure to the correct person within an Australian Government agency

(their supervisor or an authorised internal recipient)

3. provide

information that they believe tends to show, on reasonable grounds, ‘disclosable

conduct’ within an agency or by a public official.[40]

The process for receiving, assessing and either rejecting

or investigating disclosures of information under the PID Act are set

out in short form in the flowchart reproduced from the Ombudsman’s Reference

Guide to the Act.

Figure 2: Process of assessing, investigating internal disclosures under PID Act (Ombudsman's Reference Guide)

External disclosure

The Act provides a pathway for whistleblowers to make

external protected disclosures to ‘any person’ outside the agency (e.g. to the

media or an MP) in limited circumstances. The Act only enables: ‘a disclosure

to anybody, if an internal disclosure of the information has not been

adequately dealt with, and if wider disclosure satisfies public interest

requirements’ [emphasis added].[41]

Public interest considerations include for example

consideration of whether the disclosure would promote the integrity and

accountability of the Commonwealth public sector, and the nature and

seriousness of the conduct.[42]

Emphasis on

Internal Disclosure

The emphasis of the PID Act is on internal

disclosures within government rather than supporting and encouraging

whistleblowers to ‘go public’. As explained by the Attorney-General in his 2013

second reading speech:

A main purpose of the bill is to establish clear procedures

for allegations of wrongdoing to be reported by public officials and for

findings of wrongdoing to be rectified. The emphasis on the scheme is on the

disclosure of wrongdoing being reported to and investigated within government.

To this end, the bill places obligations on principal officers of agencies to

ensure that public interest disclosures are properly investigated and that

appropriate action is taken to deal with recommendations relating to their

agency. In short, these are obligations to act on disclosures of wrongdoing and

to fix wrongdoing where it is found. A well-implemented and comprehensive

scheme should lead to a discloser having confidence in the system, and remove

incentive for the discloser to make public information to parties outside

government.[43]

The Act does not protect

external disclosure of intelligence information (or conduct). Within the six intelligence

agencies, only internal disclosures are permitted (see below).

Emergency disclosure

There is also provision for ‘emergency

disclosures’. Where there is a substantial and imminent danger to health and

safety or to the environment, the internal disclosure can be by-passed and

disclosures can immediately be made public in accordance with specified

conditions.[44]

Protections

Public officials who make a disclosure in accordance with

the PID Act have protections from reprisal actions and immunity from

civil, criminal and administrative liability for making the disclosure. In

addition, no contractual or other remedy or right may be enforced or exercised

against the individual on the basis of that disclosure.[45]

The Act specifies examples of reprisals, including

dismissal, injury in employment, discrimination in employment, or alteration of

employment.[46]

Oversight

The Commonwealth Ombudsman and the Inspector General of

Intelligence and Security (IGIS) are the statutory authorities responsible for oversight

of the PID Act. These bodies are also responsible for promotion of the PID

Act, and monitoring and reporting on its operation.[47]

The Act uses the term investigative agency as a

catch all for the Ombudsman, the IGIS and any; agency prescribed under the PID

rules. No agency has been prescribed.[48]

Role of the

Commonwealth Ombudsman

The public interest disclosure functions of the Ombudsman

are set out in the PID Act and section 5A of the Ombudsman Act 1976

and include:

- acting

as an ‘investigative agency’ and ‘authorised internal recipient’ under the PID

Act[49]

- investigating

disclosures under the PID Act or using separate powers under the Ombudsman

Act

- assisting

principal officers, authorised officers, public officials and former public

officials in relation to the operation of the PID Act[50]

- conducting

educational and awareness programs relating to the PID Act for agencies,

public officials and former public officials[51]

- assisting

the IGIS with its functions under the PID Act[52]

- determining

standards relating to: disclosure procedures, conduct of PID investigations,

and standards for PID investigation reports, and standards for PID reporting by

agencies and

- receiving

notices from agencies relating to the allocation of disclosures and decisions

not to investigate disclosures.[53]

Further, the way a disclosure has been allocated or

investigated, or the allocation or investigation decision, may be the subject

of a complaint under the Ombudsman Act.

Intelligence

agencies and the PID Act

Under the Act, intelligence information (as

defined in section 41) is exempted from the public (external) disclosure

provisions. Intelligence information cannot be the subject of an external disclosure

(such as provision of information to the media or an MP).[54]

Likewise it cannot be the subject of ‘emergency disclosure’ or ‘legal

practitioner disclosure’. Intelligence information can only be the subject of an

internal disclosure.[55]

The Bill does not propose to alter that position.

Inspector-General

of Intelligence and Security (IGIS)

The Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS)

has oversight of the 6 intelligence agencies subject to the PID scheme,[56]

and in relation to the intelligence functions of the Australian Criminal

Intelligence Commission (ACIC) and the Australian Federal Police (AFP).[57]

It has the same allocation, investigation and education functions as the

Commonwealth Ombudsman.[58]

Conduct engaged in by intelligence agencies and by public

officials of these intelligence agencies which relates to the proper

performance of their functions and powers is excluded from the PID Act.[59]

IGIS

responsibilities include overseeing the actions of intelligence agencies to

ensure they comply with the PID scheme, as well as assisting current and former

public officials of intelligence agencies in relation to the operation of the PID

Act.

The PID Act in Practice

Judicial observation

In 2019, Justice Griffiths of the Federal Court gave a

less than complimentary assessment of the readability of the PID Act,

describing it as ‘technical, obtuse and intractable’.[60]

In a judgment regarding an unsuccessful application by a

whistleblower employee of the Department of Parliamentary Services, he recounted:

In a somewhat understated submission, the respondents

described the PID Act as involving “a number of complex interlocking

substantive provisions and definitions”. The legislation might more

accurately be described as technical, obtuse and intractable …This may reflect

the multiple compromises which have been struck in weighing the competing

public and private interests. Those competing interests are reflected in the

objects of the PID Act, as set out in s 6 … It is acknowledged that

reconciling these competing objects is not an easy exercise and is one for the

Parliament. But the outcome is a statute which is largely

impenetrable, not only for a lawyer, but even more so for an ordinary member of

the public or a person employed in the Commonwealth bureaucracy [emphasis

added].[61]

Extent of

wrongdoing disclosed

The statutory Moss Review (2016), discussed below, conducted

after the Act had been in operation for only two and a half years, found that

the PID Act ‘has enabled disclosure of fraud, serious misconduct and

corrupt conduct, but only to a limited extent’.[62]

More detailed data about allegations raised in PIDs since the

completion of the Moss Review is evident in the Annual Reporting of the

Ombudsman and the IGIS.

Data: Recent

number of disclosures

In 2021–22, 257 PIDs were received across the Commonwealth

public sector (compared with 333 in 2020–21, a 23 per cent decrease). A further

428 disclosures were assessed as not meeting the requirements of the PID Act,

and not considered to be public interest disclosures, compared with 400 in

2020–21 (7 per cent increase).[63]

In terms of PIDs lodged within the jurisdiction of the

IGIS, there were 10 PID Act disclosures (received or allocated) during

2021-22, and 16 PID disclosures during 2020-21.[64]

Data: Nature

of allegations

The Annual Reporting on the operation of the PID Act

by the Commonwealth Ombudsman provides insights into the broad categories of

allegations made of disclosable conduct during 2020-21 (marked in navy blue in

graphic) compared to 2021-22 (marked in light blue in graphic). The data

indicates that ‘maladministration’ and ‘conduct that may result in disciplinary

action’ were the two most common categories of allegation made.[65]

Figure 3: Main categories of allegation in PIDs, 2020-2022

Source: Ombudsman

Are the

laws working for whistleblowers?

Critics have argued that reforms should offer more

specific support to whistleblowers aimed at addressing what is often the high

personal and financial cost of making a whistleblowing disclosure.[66]

According to Professor A. J. Brown and Kieran Pender:

Research shows that a substantial proportion of

whistleblowers suffer serious repercussions for doing so, of whom barely a

fraction receive any protection. This injustice has a chilling effect… Among

the few claims for remedies or compensation brought under any federal law –

including less than a dozen cases under the PID Act since 2013 – almost

none have been successful.[67]

Protecting Australia’s Whistleblowers: The Federal

Roadmap (2022) made the following findings based on detailed primary

sources research:

Griffith University’s Whistling While They Work 2 project … surveyed

over 17,000 employees from 46 organisations, including 5,500 whistleblowers and

3,500 managers and governance staff who observed or dealt with whistleblowing

cases … [it] found no improvement in the outcomes for public sector

whistleblowers [since 2008] … according to the managers and governance staff,

56 per cent of public interest whistleblowers suffered serious repercussions –

whether as indirect/collateral damage, or in 30 per cent of cases, as direct

harm including adverse employment actions, harassment or intimidation. This was

despite the fact that in over 90 per cent of cases, managers and governance

staff assessed the whistleblower as being correct and deserving of the

organisation’s support … only half (49 per cent) of these whistleblowers were

identified as having received any remedy for the detriment they suffered – even

marginal or insufficient remedies – despite its seriousness. Even fewer (43 per

cent) of those who suffered serious direct harm received any remedy. Overall,

less than six per cent received any compensation for the employment, health or

personal impacts. The low proportion of meaningful remedies for whistleblowers,

even when managers identify that they suffered serious repercussions and

deserved support, shows clearly that the rights intended by law were not

translating into reality.[68]

Legal Costs

Section 18 of the existing Act departs from the usual rule

regarding the allocation of legal costs (which would normally mean the losing

party is required to pay the costs of the winner), to provide some measure of

reassurance in advance to a prospective discloser. It provides that in Federal

Court proceedings (including appeals) where an applicant seeks orders for an

order preventing or injuncting reprisals, or requiring compensation, an apology

or reinstatement or other protections, the applicant cannot be ordered to pay

the other party’s costs except where the proceedings were brought vexatiously

or without reasonable cause, or where unreasonable actions were taken that

caused legal costs to be incurred.

The present Bill does not alter this position in the Act

in relation to costs.

Moss Review

The first statutory review of the PID Act was

completed in July 2016 (Moss Review).[69]

It was undertaken by Philip Moss AM, the former Integrity

Commissioner and head of the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement

Integrity (ACLEI) between 2007–14.

The Moss

Review was established in January 2016 under section 82A of the PID

Act, which required a review of the PID Act to be commenced within two

years of commencement of the Act.

Terms of

Reference

The terms of reference were to examine:

1. the impact of the Act on individuals seeking to make

disclosures in accordance with its provisions;

2. the

impact of the Act on agencies, including any administrative burdens imposed by

investigation and reporting obligations in the Act;

3. the

breadth of disclosable conduct covered by the Act, including whether

disclosures about personal employment-related grievances should receive

protection under the Act; and

4. the

interaction between the Act and other procedures for investigating wrongdoing,

including Code of Conduct procedures under the Public Service Act 1999

and the Commonwealth's fraud control framework.[70]

Main Findings

The Moss Review found that the PID Act had

only been partially successful, with few individuals who had made disclosures

feeling supported, and agencies finding the scheme difficult to apply. It

described the perspective of both whistleblowers and that of Commonwealth

agencies, finding:

The experience of whistleblowers under the PID Act

is not a happy one. Few individuals who had made PIDs reported that they felt

supported. Some felt that their disclosure had not been adequately investigated

or that their agency had not adequately addressed the conduct reported. Many

disclosers reported experiencing reprisal as a result of bringing forward their

concerns.

The experience of agencies is that the PID Act

has been difficult to apply. Most agencies noted that the bulk of disclosures

related to personal employment-related grievances and were better addressed

through other processes. Agencies noted also that the PID Act’s

procedures and mandatory obligations upon individuals are ill-adapted to

addressing such disclosures…

The relative newness of the PID Act framework may be

part of the cause, yet the Review concludes that the current PID Act

provisions impair the effective operation of the framework. In this respect,

the Review notes that there are two principal challenges:

-

The PID Act’s interactions

with other procedures for investigating wrongdoing are overly complex.

Investigations into disclosures are often isolated from other integrity and

accountability legislative frameworks by the operation of the secrecy offences.

Key investigative agencies have been omitted. There is also a perception that the

PID Act framework is legalistic, making it difficult to resolve a PID.

-

The kinds of disclosable

conduct are too broad, rather than being targeted at the most serious

integrity risks, such as fraud, serious misconduct or corrupt conduct. The

Review found that while the PID Act is helping to bring to light

allegations of serious wrongdoing, these disclosures are in the minority. Most

PIDs concern matters that are better understood as personal employment-related

grievances, for which the PID Act framework is not well suited.

The Review considers that, by adopting legalistic approaches

to decision-making, the PID Act’s procedures undermine the

pro-disclosure culture it seeks to create.[71]

Recommendations

The Moss Review made 33 recommendations to improve

the operation of the PID Act. A summary table of recommendations is

provided at the Appendix, which indicates which recommendations have been

addressed in the Bill.

Moss explained that ‘the Review’s recommendations are

intended to encourage and instil a pro-disclosure culture [within Commonwealth

agencies]’.[72]

In summary, the recommendations included:

- better

targeting the scheme to focus on significant wrongdoing such as fraud, serious

misconduct and corrupt conduct

- providing

better support for disclosers, or potential disclosers, by enabling them to get

help and advice from lawyers, and other professional support services

- providing

witnesses to the wrongdoing with the same protections as disclosers from

detriment, and immunity from civil, criminal and administrative liability

- strengthening

the ability of the Commonwealth Ombudsman and the Inspector-General of

Intelligence and Security to scrutinise and monitor decisions of agencies about

disclosures

- appointing

additional investigative agencies under the PID Act

- redrafting

the Act with a ‘principles-based’ approach (as compared to prescriptive

procedural requirements)

- including

as permissible additional external disclosure when disclosure within an agency

has not been actioned as required by the statute

- inserting

an explicit requirement to accord procedural fairness to a person against whom

wrongdoing is alleged before making adverse findings about that person, and

- retaining

criminal offences for revealing identifying information but repealing the

prohibitions on not using and not disclosing protected information.[73]

Other inquiries

and reactions

The Bill also seeks to respond to recommendations of two

other Inquiries.

- On

30 November 2016, the Senate referred an

Inquiry into Whistleblower Protections in the Corporate, Public and Not-for-profit

Sectors to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and

Financial Services. That Committee tabled its report

in the Parliament in September 2017 (the PJCCFS Report). The inquiry primarily

examined the private sector whistleblowing scheme under the Corporations Act

but some recommendations related to the public sector whistleblowing scheme

under the PID Act. The Bill responds to Recommendations 6.1 and 6.3 of

the PJCCFS Report. On 4 July 2019, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Intelligence and Security commenced an inquiry into the impact of the exercise of law enforcement

and intelligence powers on the freedom of the press, as a result of a referral

by then Attorney-General, Christian Porter. The Committee reported

in August 2020 (the PJCIS report). The Bill responds to Recommendations 10 and

11 of the PJCIS report.

National

Anti-Corruption Commission laws

On 30 November 2022, the National

Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2022 (NACC Act) and National Anti-Corruption

Commission (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Act 2022 (NACC Consequentials Act) passed the Parliament.

These Acts received Royal Assent on 12 December 2022. It is intended that the main

provisions of the NACC legislation will commence in mid-2023 on a day to be

fixed by proclamation.[74]

The passage of the NACC legislation is relevant to the

present discussion of proposed amendments to the PID Act, for two

reasons:

- the NACC Consequentials Act will make amendments to the PID Act and

- there

is a need for the system for investigation of disclosures under both schemes to

operate together in parallel but without unnecessary complexity and confusion.

Further detail on the NACC Bills can be found in the

relevant Bills

Digest published in November 2022.

In terms of the interaction of the NACC legislation and

the proposed amendments to the PID Act, the Attorney-General has

indicated that the Government’s aim is for the PID amendments to be in place by

the time the NACC is established in mid-2023.[75]

The second

reading speech for the present Bill states that the Bill will amend the

NACC legislation to reflect [the proposed] amendments to whistleblower

protections in the PID Act ‘to ensure both regimes provide strong

protections for whistleblowers’.

Overview of

disclosure provisions of the NACC legislation

The National

Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2022 provides a range of protections to

persons who provide evidence or information about a corruption issue to the

NACC. This is designed to enhance the effectiveness of the NACC by encouraging

people to provide information about corruption issues without fear of

retribution.

Part 4 of the NACC Act deals with protections for

disclosers.

Section 23 outlines what is meant by a NACC disclosure. Section

24 affords immunity from civil, criminal and administrative liability to any

person who provides information about a corruption issue to the NACC. Sections 29

and 30 provide for protection against reprisals or threat of reprisals. These

are complementary protections to those provided under the PID Act (paragraph 10(1)(a) and

subsection

19(1)).

The NACC Act also provides protection from the

enforcement of contractual or other remedies against a person due to their NACC

disclosure (paragraph 24(1)(b)), which is equivalent to paragraph 10(1)(b) of

the PID Act.

Another relevant provision of the NACC Act is section

35, concerning mandatory referral of PID Act disclosures, which provides

that staff members of Commonwealth agencies who become aware of certain

corruption issues in the course of performing functions under the PID Act

are required to refer those corruption issues to the NACC Commissioner.

Committee

consideration

Legal and

Constitutional Affairs Committee

The Bill was referred on 1 December 2022 to the Senate

Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs for

inquiry. The Committee had received 23 submissions

by early February 2023. Some of these submissions are discussed below. At the

time of writing, the Committee was due to report by 14 March 2023.

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

has reported on its initial consideration of the Bill.[76]

The Committee sought the advice of the Attorney-General on a number of matters,

some of which are discussed below under Key issues and provisions.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Liberal-National

Coalition

As a member of the Joint

Select Committee on National Anti-Corruption Commission Legislation,

Senator Paul Scarr stated

[emphasis added]:

We heard some very strong testimony that there needs to be reform

with respect to the management of whistleblowers, in particular, so that

whistleblowers, whether they are in the public sector or the private sector,

are given the support and guidance they need in order to effectively discharge

the important role which they conduct and carry out in our civic society. I

think the evidence is there that, at this point in time, there's a maze of laws

that need to be navigated by whistleblowers. As someone who used to be a

whistleblower officer for a major company in the private sector, I think it's

absolutely important that whistleblowers have the courage to put up the red

flag with respect to issues and should be given support and should be able to

get the guidance they need to discharge their important role in our civic

society.

This may suggest that the Coalition supports some degree

of reform to laws governing whistleblower protections, although it is not clear

if the Coalition endorses the measures adopted by the Bill.

Greens

Justice portfolio spokesperson for the Greens, Senator David

Shoebridge, said the Bill ‘excludes whistleblower complaints with a mixture of

employment elements’, which he claims goes a step further than the related

recommendation from the Moss Review.[77]

The Guardian reported on Shoebridge’s view that:

Labor’s whistleblower bill goes too far in excluding personal

conduct such as sexual harassment complaints from protection … Examples in the

bill of conduct that could no longer be the subject of a whistleblower

complaint include interpersonal conflicts, bullying or harassment; disputes

about promotions; terms and conditions of employment; and disciplinary action

including suspension or termination.[78]

Crossbench

At the time of debate of the NACC legislation in 2022, a

group of cross-benchers called for a Whistleblower Protection Commissioner.[79]

In particular, Independent MP Helen Haines has continued

to advocate establishment of a whistleblower protection commission. Her

submission to the Committee inquiry into the current Bill refers to the need to

provide legal support to whistleblowers. She submits:

The formation of an independent whistleblower protection

commission is critical to support whistleblowers who are navigating the legal

system. This was a key pillar of my 2020

Australian Federal Integrity Commission Bill and received support in the

Advisory Report for the Joint Select Committee examining the NACC Bill. A

Whistleblower protection commission would operate similarly to the Fair Work

Ombudsman or human rights commissions, and should provide legal support to

whistleblowers, enforce whistleblower protection laws and implement

whistleblower protections[80]

Dr Haines also suggested that Parliament should:

Vest the Fair Work Commission with new jurisdiction to

conciliate whistleblowing claims against public and private employers to ensure

easier, consistent access to remedies.[81]

During debate over the NACC legislation, Dr Haines stated ‘I

don’t want to see a powerful corruption commission set up without whistleblower

protections. I can’t rest as a parliamentarian until I know whistleblowers will

be protected. We’ve seen plenty of examples where they come to grief.’[82]

Teal Independent, Kate Chaney, also stated

during the second reading debate on the NACC legislation that:

the priority amendments to the Public Interest Disclosure Act

need to be substantive and work together with later amendments to support

disclosure of relevant information with necessary protection.

Andrew Wilkie

During debate on the NACC Bills in November 2022, Andrew

Wilkie stated: ‘the PID Act is seriously deficient and urgently in need

of reform’.[83]

Moreover, during private members’ business, Mr Wilkie moved

that the House call on the Government to:

(a) urgently

reform the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 and Corporations Act

2001 to ensure that protections for whistleblowers are strong,

comprehensive and fit for purpose; and

(b) establish

an empowered and well-resourced Whistleblower Protection Commissioner to

facilitate the effective implementation and enforcement of whistleblower

protections.

Lambie

Alliance

During debate on the NACC legislation, Senator Lambie expressed

concern about whistleblower protections for journalists, stating that:

This is a grey area when it comes to journalists, and that

worries me considerably. Without them, many things never come out into the

open.

Senator David

Pocock

Senator David Pocock indicated his support for strong

whistleblower protection laws, by helping Griffith

University’s Centre for Governance and Public Policy, Transparency

International and the Human Rights Law Centre launch a major report on the

topic co-authored by AJ Brown and Kieran Pender in November 2022.[84]

Senator Pocock also stated

during debate on the NACC legislation in 2022 that:

Whistleblower protections are fundamental to ensuring

integrity. I welcome the whistleblower reforms to be introduced at the end of

this week and call on the government to act as quickly as possible to establish

a whistleblower protection commissioner and provide whistleblowers with the

protection they deserve. There should be really clear processes and pathways

for people in public service and in the private sector to come forward with

information that may well be politically inconvenient and that may be, frankly,

embarrassing for Australians but is crucial if we are to continue to improve

the open democracy we have and to have all the benefits of living in such a

system.

Position of

agencies, experts, interest groups and stakeholders

IGIS

The Inspector General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS)

made a submission to the Committee inquiry into the Bill. It outlined its role

in terms of oversight of PID disclosures from the intelligence agencies. It

stated that the IGIS received ten public interest disclosures about the conduct

of the intelligence agencies during 2020-21. Further it stated:

In terms of the amendments contained in the Bill and their

impact on the IGIS' role under, and oversight of, the PID framework, the IGIS

does not have any specific issues to raise for the Committee's consideration. [85]

Australian Human

Rights Commission

The Australian Human Rights

Commission, suggested that staff of MPs and Senators (under the Members of

Parliament (Staff) Act 1984 (MOPS Act)) be given the option to

make protected public interest disclosures under the PID Act. It stated:

For the reasons given in the Set the Standard report

into Commonwealth parliamentary workplaces, the Commission does not support the

proposal in the Bill to clarify that the PID Act does not apply to

parliamentary staff. The Commission agrees with the comments made in the report

of the 2009 parliamentary inquiry that led to the PID Act that

parliamentary staff may have insider access to information, be in a position to

observe serious conduct contrary to the public interest and face risks of

reprisal for speaking out. They should be supported to do so and provided with

the protections afforded by the PID Act. The Commission recommends that

parliamentary staff should be included as ‘public officials’ in the PID Act.[86]

Victorian

IBAC

The Victorian Independent Broad-Based Anti-corruption Commission

(IBAC) commented on the proposal of the Bill to remove MPs and staff engaged

under the MoPs Act from the definition of ‘public official’. It noted:

The effect of removing Members and MoP Staff from the

definition means they will need to make disclosures under the National

Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2022 (NACC Act) to be protected against any

civil, criminal, or administrative liability.[87]

Human

Rights Law Centre

Senior Lawyer at the Human Rights Law Centre and co-author

of a recent report

on whistleblowing, Kieran Pender, stated:

The amendments to reform the PID Act are an important

first step to better protect and empower Australian whistleblowers … But they

are just that - a first step. These technical changes make administrative

improvements but do not deal with fundamental issues.[88]

Mr Pender is one of the authors of a detailed contribution

to the debate on whistleblower laws published late in 2022 by the Griffith

University’s Centre for Governance and Public Policy, Human Rights Law Centre

and Transparency International, in the form of a report calling for more far-reaching

reform of what is described as Australia’s ‘incomplete and messy’ patchwork of

whistleblower laws.[89]

The report:

urges the government to establish a federal whistleblower

protection authority to oversee and enforce Australia’s whistleblower

protections, create a new federal law to consolidate patchy safeguards for

private sector whistleblowers and stronger protections for those who make

disclosures to the media and members of parliament. [90]

Professor A.

J. Brown

Professor A. J. Brown, Professor of Public Policy and Law,

Griffith University, has a long record of publication in the field of

whistleblower protection research. He has led six Australian Research Council

projects into public integrity and governance reform, including three into

public interest whistleblowing, and the 2020 ARC Linkage Project, 'Australia's

National Integrity System: The Blueprint for Reform'. He is also a Fellow of

the Australian Academy of Law.[91]

In a June 2022 interview with ABC’s The Business programme, he said:

Our laws are still very reliant on whistleblowers themselves

having the legal resources [and] the money to be able to go to court and fight

for their own protection. A big gap is the lack of a whistleblower protection

authority.[92]

In an opinion piece on the Bill, published in November

2022 Professor Brown argued:

However worthwhile, the “priority amendments” recommended by

a now out-of-date 2016 review involve few steps towards addressing the deeper

defects in the laws. Most of those 2016 recommendations were designed to make

it easier for agencies to navigate their roles, more than improve the

protections.[93]

Professor Brown said Australia had ‘rapidly fallen behind’

other democratic countries when it came to protecting whistleblowers. ‘Complex

laws, full of loopholes and lacking practical support, are not fulfilling their

purpose of protecting those who speak up’, Brown said.[94]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill states:

Some of the proposed amendments contained in this Bill would

impact the respective workloads of the Ombudsman and the IGIS.[95]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[96]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee

on Human Rights had no comment on the Bill.[97]

Key issues

and provisions

Schedule

1—Main amendments

Part 1 - Personal work-related

conduct

Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Bill proposes amendments to

create a new category of conduct, namely ‘personal work-related conduct’, and

to remove it from the scope of ‘disclosable conduct’.

Disclosable

Conduct

The meaning of ‘disclosable conduct’ is important

as it sets the boundaries for when public officials may make (internal or

external) public interest disclosures under section 26.

‘Disclosable conduct’ only includes conduct of an agency,

public official, or contracted service provider for a Commonwealth contract.[98]

The types of disclosable conduct are conduct

that:

- contravenes

a Commonwealth, state or territory law

- in

certain circumstances, contravenes a law in force in a foreign country

- perverts

the course of justice or involves corruption of any other kind

- constitutes

maladministration including conduct based on improper motives, or that is

unreasonable, unjust or oppressive, or is negligent

- is

an abuse of public trust

- is

fabrication, plagiarism or deception in relation to scientific research

- results

in wastage of public money or public property

- unreasonably

results in a danger to health or safety or unreasonably results in or increases

a risk of danger to health or safety

- results

in danger to the environment or increases the risk of danger to the environment

- is

of a kind prescribed by the Public Interest

Disclosure Rules (PID Rules).[99]

Disclosable conduct is also:

- conduct

where a public official abused his or her position, and

- conduct

that could give reasonable grounds for disciplinary action.[100]

It is immaterial whether the disclosable conduct in

question occurred before or after commencement of the PID Act; whether

the agency involved has ceased to exist; or whether the particular public

official or contract service provider involved in the conduct no longer hold

these particular positions.[101]

Non-disclosable

matters

Conduct is not disclosable if it relates to political or

expenditure matters with which a person disagrees.[102] Attempted whistleblowing on

the grounds of disagreement with government policy or priorities is not

protected by the Act. As set out in section 31:

conduct is not disclosable conduct if it relates only to a

policy or proposed policy of the Commonwealth Government; or action that has

been, or is proposed to be taken by a Minister … or amounts, purposes or

priorities of expenditure or proposed expenditure relating to such a policy … or

action with which a person disagrees.

Policy intent

The aim of these amendments is to narrow the range of

conduct that can be reported, disclosed or otherwise be the subject of a

whistleblower complaint. The aim is to exclude complaints about minor

‘personal’ issues from the PID scheme. This is evident from the second reading speech,

which states an intent ’to focus the Act on integrity wrongdoing, such as fraud

and corruption’.[103]

The Government asserts that these amendments implement

Moss Recommendations 5 and 6. These advocated ‘a stronger focus on significant

wrongdoing’ and ‘the general exclusion of personal employment-related

grievances’.[104]

The Moss Review recounted:

Submissions received from agencies noted that the

overwhelming majority of disclosures concerned issues like workplace bullying

and harassment, forms of disrespect from colleagues or managers, or minor

allegations of wrongdoing … The Review recommends that the legislation redefine

the scope of disclosable conduct to focus on fraud, serious misconduct and

corrupt conduct. This approach is not to suggest that agencies should ignore

other forms of wrongdoing or workplace conflict. The Review notes that such

matters are better resolved through less formal processes available through

existing administrative and statutory schemes, such as performance management,

merits review, or disciplinary conduct procedures.[105]

Narrowing the scope of disclosable conduct may have

administrative benefits for the 176 Commonwealth agencies who can receive PID

disclosures and decide upon and investigate them. This will be the case if

the new provisions are easy to understand and apply.

Review

recommendations and corresponding Item Number in Schedule 1 to the Bill

| Precis of topic |

Recommendations |

Item Number

|

Section |

| ‘Personal

work-related conduct’ |

Moss

Review Recommendation # 5 & 6 |

Items 1,3

and 4 |

Amends section

8, inserts new subsection 29(2A) and new section 29A |

| Narrowed

definition of disclosable conduct |

Moss # 7 |

Item 2 |

New

paragraph 29(2)(b) |

| Definition

of personal work-related conduct, closer alignment of private and public

sector whistleblowing provisions |

PJCIS Press

Freedoms Report, #9 (in part)[106] |

Items 3 and

4 |

New subsection

29 (2A) and new section 29A |

New category of exclusion

Items 3 and 4 of Schedule 1 provide that ‘personal

work‑related conduct’ (‘PWRC’) is excluded from the definition of

‘disclosable conduct’ in section 29 of the PID Act .

The meaning of ‘personal work‑related conduct’

is defined in new section 29A, inserted by item 4, as

follows:

conduct (by act or omission) engaged in by a public official

(the first official) in relation to another public official (the second

official) that:

(a) occurs in

relation to, or in the course of, either or both of the following:

(i)

the second official’s engagement or appointment as a public official;

(ii)

the second official’s employment, or exercise of functions and powers,

as a public official; and

(b) has, or

would tend to have, personal implications for the second official.

Examples of PWRC to be excluded

Item 4 gives the following examples of personal

work‑related conduct:

- conduct

relating to an interpersonal conflict (including, but not limited to, bullying

or harassment)

- conduct

relating to a transfer or promotion

- conduct

relating to terms and conditions of engagement or appointment

- disciplinary

action taken

- suspension

or termination of employment or appointment

- other

conduct that would give rise to review rights under section33 of the Public Service Act

1999.[107]

Conduct not excluded: Reprisals

The exclusion of personal work-related conduct

is modified by Item 3, which inserts new subsection 29(2A). It

provides that three types of PWRC will remain within the ambit of ‘disclosable

conduct’. These are exemptions from the proposed exclusion of

personal work-related conduct as disclosable conduct.

The first is where the conduct would constitute taking

a reprisal against another person. New paragraph

29(2A)(a) provides that reprisal conduct is not excluded from the Act. The

Second Reading speech indicates that PWRC which ‘amounts to a reprisal’ is not

intended to be excluded from the list of ‘disclosable conduct’.[108]

Background: Reprisal provision

Section 13 of the PID

Act defines ‘what constitutes taking a reprisal’. It provides that a

person takes a reprisal if the person by act or omission causes any detriment

to another person (the second person) because they believe or suspect that the

second person or any other person made, may have made or proposes to make a

public interest disclosure, and that belief or suspicion is the reason, or part

of the reason, for the act or omission.[109]

Detriment is defined to include any

disadvantage including, but not limited to, dismissal, injury in relation to

employment, alteration of an employee’s position to their detriment and

discrimination between an employee and other employees of the same employer

(s.13(2)).

Background:

Moss Review data on reprisals

Some 75% per cent of respondents to Moss Review’s

online survey who had made an internal disclosure stated they had experienced

reprisal after making a PID.[110]

The Ombudsman also published relevant data:

In 2021–22, Commonwealth agencies reported 52 claims of

reprisal, an increase from 27 the previous year. The most common types of

conduct alleged were bullying, disadvantage to employment and, unreasonable

management action. Agencies reported that, on investigation, no claims were

substantiated.[111]

Conduct not excluded: public confidence or significant

implications for an agency

There are two additional proposed exemptions from the

broad exclusion of PWRC.

New paragraph 29(2A)(b) provides that where the PWRC

is ‘of such a significant nature that it would undermine public confidence in

an agency (or agencies)’, then it is not excluded, and remains subject to the

disclosure regime.

New paragraph 29(2A)(c) clarifies that where PWRC

‘has other significant implications for an agency (or agencies)’ it is not

excluded.

Comment

This group of amendments proposes narrowing the type of

disclosable conduct under the Act.

Firstly, however the definition of PWRC is complex and

opaque. The Bill offers no guidance on the phrases ‘conduct of such a

significant nature’ and ‘significant implications’.

Secondly, both the Second Reading Speech and Explanatory

Memorandum employ terms not in the Bill. The Speech says disclosures of PWRC

can still be investigated ‘where it is symptomatic of a larger, systemic

concern within an agency.’ [112]

However, the Bill does contain the term ‘systemic wrongdoing’ or ‘systematic

concern’.

Thirdly, the phrase suggested by Moss Recommendation 5 to

exclude ‘conduct solely related to personal employment-related grievances’

is not employed in the Bill.[113]

It is useful to revisit the recommendations of the Moss

Review in detail. Related text of the Moss Review was couched in

terms of an additional recommendation - although was unfortunately not numbered

as such. Yet it remains highly relevant:

The Review recommends that the PID Act be amended

to adopt a general exclusion for personal employment-related grievances. These

amendments will need to ensure that in cases when a disclosure that includes

both an element of personal employment-related grievance, as well as an element

of other wrongdoing, the latter element could still be the subject of a PID.

These amendments should also be reviewed after their implementation to ensure

that they achieve the policy intention. [114]

Proposed narrowing of ‘conduct that could result in

disciplinary action’

The Bill proposes to narrow the types of wrongdoing that

can be subject of a PID by excluding less serious breaches of the APS Code of

Conduct, such as those which would not involve reasonable grounds for

dismissal. This is to implement Recommendation 7 of the Moss Review.

As discussed above, the definition of disclosable

conduct in section 29 of the PID Act includes conduct that could

give reasonable grounds for disciplinary action.[115]

Item 2 repeals and replaces paragraph 29(2)(b), to provide that

conduct which could give reasonable grounds for disciplinary action is only disclosable

conduct if it could give reasonable grounds for termination.

Comment: Intermingled disclosures

The Moss Review discussed the likelihood that—in

some instances—matters that on first examination can be characterised as

‘personal’ issues may still also raise broader issues of agency

maladministration or agency wrongdoing. It notes:

The Review became aware that, occasionally, a personal

employment-related grievance can be symptomatic of a larger, systemic concern,

such as discriminatory employment practices or nepotism. Such concerns should

attract the protection of the PID Act. To ensure that these matters can

be the subject of a disclosure, the Review recommends that Authorised Officers

be granted discretion to treat a personal employment-related grievance as a

disclosure under the PID Act if they consider it relates to a systemic

issue.[116]

The Review stated:

These amendments will need to ensure that in cases when a

disclosure that includes both an element of personal employment-related

grievance, as well as an element of other wrongdoing, the latter element could

still be the subject of a PID. These amendments should also be reviewed after

their implementation to ensure that they achieve the policy intention.[117]

Position of stakeholders

Public Service Commissioner

The Australian Public Service Commissioner Peter Woolcott,

expressed support for the PWRC changes, in a submission to the Legal and

Constitutional Affairs Committee inquiry into the Bill:

Legislating this change … will provide immediate and

much-needed clarity for all those in the APS who engage with the PID scheme … [T]he

administrative burden on agencies will nonetheless decrease significantly as

complaints regarding personal employment-related grievances or lower-level

misconduct are moved to the most appropriate handling framework …[118]

Greens

Greens spokesperson on Justice, Senator David Shoebridge,

said that the Bill ‘excludes whistleblower complaints with a mixture of

employment elements’, saying that this goes further than the exemption proposed

by the Moss Review.[119]

He said: ‘the carve out for employment-related matters is set at far too high a

level … We know that whistleblowers too often lose their jobs or their careers

from speaking out, so we can’t have a PID scheme that excludes all employment

disputes’.[120]

Broader research-informed perspective

In 2008, researchers led by Professor Brown noted that it

is difficult to define and identify what are purely ‘personal’ or ‘private’

grievances within an agency, stating:

it is important that organisational systems recognise the

degree to which personal and public interest matters are intertwined,

otherwise, issues of public interest can go overlooked and employees might be

left subject to reprisals simply because personal interests are also involved.[121]

Not infrequently, whistleblowers have been targeted with

personalised criticism and pressure by organisational management. Sometimes

attempts are made to characterise whistleblowing as misguided actions of an

individual with a personal grudge, character failings or even psychiatric

issues.[122]

Referral of a whistleblower for psychiatric assessment

sometimes can represent a form of retaliation, according to Kenny et al. in the

Journal of Business Ethics. This is because the stigma associated with

‘mental illness’ in society ‘can be used by retaliatory organizations seeking

to discredit a whistleblower’.[123]

Fotaki et al found that some ‘organizations position whistleblower subjects as

mentally unstable and unreliable individuals, to undermine their claims’.[124]

In relation to the UK whistleblower protection

legislation, British barrister, John Bowers stated that it is important to

ensure that legislative drafting does not generate an organisational incentive

to discredit whistleblowers:

One area of tension lies between the interest in confining

the legislation’s protection to those responsibly acting in the public

interest, and a concern as to the chilling effect if protection is uncertain.

The most obvious example lies in the test for good faith, which focusses on

motive. Whilst those who act other than in the public interest are therefore

not protected, employers are encouraged to discredit the whistleblower rather

than focussing on what they disclose.[125]

One solution to this could be to apply a different test.

The UK’s whistleblower provisions in employment legislation provide that the

category of external disclosures (for example, to the media) that are protected

is only available where disclosures are not made for personal gain.[126]

International comparison of reprisal provisions

The anti-reprisal provisions of the PID Act require

the whistleblower to prove to the Federal Court that a Commonwealth agency had

a conscious ‘belief or suspicion’ of a disclosure as a positive ‘reason’ for

the detrimental conduct … before remedies might be granted by the Court.

Paragraph 13(1)(c) relating to reprisals states that a discloser must persuade

the Court that the employer agency’s ‘belief or suspicion is the reason, or

part of the reason, for the [reprisal] act or omission’.[127]

By contrast, the EU Directive on the protection of

persons who report breaches of Union law (2019), places the onus on the

agency, in Article 21 ‘Measures for Protection against retaliation’:

5. In proceedings before a court or other

authority relating to a detriment suffered by the reporting person, and subject

to that person establishing that he or she reported or made a public disclosure

and suffered a detriment, it shall be presumed that the detriment was made in

retaliation for the report or the public disclosure. In such cases, it shall be

for the person who has taken the detrimental measure to prove that that measure

was based on duly justified grounds.[128]

The Preambular text to the EU law clearly states an

intention to places the onus on the agency:

Retaliation is likely to be presented as being justified on

grounds other than the reporting and it can be very difficult for reporting

persons to prove the link between the reporting and the retaliation, whilst the

perpetrators of retaliation may have greater power and resources to document

the action taken and the reasoning. Therefore, once the reporting person

demonstrates prima facie that he or she reported breaches or made a public

disclosure in accordance with this Directive and suffered a detriment, the

burden of proof should shift to the person who took the detrimental action, who

should then be required to demonstrate that the action taken was not linked in

any way to the reporting or the public disclosure. [para 93]

Stakeholder comments

The Centre for Governance and

Policy at Griffith University, Transparency International and the Human

Rights Law Centre criticised the drafting of the PWRC exclusions. In their

submission to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee they

stated:

We consider this complex drafting will not translate into

effective implementation, as experience indicates it will encourage some

agencies to treat anything that involves work-related personal conduct as being

excluded from PID Act protection, even where there is a mix of

work-related personal conduct and other (public interest) wrongdoing within a

disclosure. Such mixed disclosures are the largest single category of

disclosures, constituting around half of all whistleblowing cases, as our

empirical research has shown (see Whistling While They Work 2). Accordingly,

s.29(2A) and s.29A of the PID Act require significant redrafting to

better achieve the letter and spirit of the Moss Review’s

recommendation.[129]

Part 2—Allocation

and investigation of disclosures

This part proposes amendments to the PID Act relating

to the administrative process for allocation and investigation of PID matters.

Many of these proposed amendments aim to provide greater ‘flexibility’

in the handling of PID allocations and investigations. They create more options

for the allocation, reallocation, referral and handling of disclosures by an authorised

officer.

Other amendments propose new requirements and

clarifications to improving communication between agencies (and with

disclosers) about the handling of PID investigations.

These processes apply after it has been determined that a disclosure

meets the tests for being a ‘public interest disclosure’ (see: Figure Two: Flowchart of process, above).

Review recommendations

and corresponding Item Number in Schedule 1 to the Bill

| Precis of topic |

Recommendations |

Item Number in Bill |

Section |

| Timely provision of investigation reports to Ombudsman

or IGIS |

Moss # 3 |

Item 28 |

New subsection 51(4) |

| Additional options for allocation and investigation of

disclosures (decision by authorised officer) |

Moss Recommendation # 14 |

Item 11 |

new sections 43, 44 and 44A.

|

| Discretion to not investigate or to cease investigation

|

Moss # 31 |

Items 11, 19 and 25

|

new sections 43, 44 and

50AA new paragraph 48(1)(ga) |

| Simplification by removing scope for parallel