Introductory Info

Date introduced: 10

February 2022

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: The

Bill commences on the first 1 January, 1 April, 1 July or 1 October to

occur following Royal Assent.

The amendments apply to patents granted or issued

after 11 May 2021 in respect of income years starting on or after 1 July 2022.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Treasury

Laws Amendment (Tax Concession for Australian Medical Innovations) Bill 2022

(the Bill) is to amend the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997) to introduce a ‘patent box’ tax regime.

The patent box regime aims to incentivise companies to:

- base

their medical and biotechnology research and development (R&D) operations

in Australia and

- commercialise

their patents in Australia.[1]

The Bill fully implements the ‘Patent Box – tax concession

for Australian medical and biotechnology innovations’ measure from the 2021–22

Federal Budget.[2]

Background

What is a patent box?

A patent box is a tax regime that provides a lower or

concessional tax rate for income derived from certain forms of intellectual

property (IP)—typically patents but sometimes other

forms of IP such as designs and copyright material.

Patent box gets its name from the box on an income tax

form that companies check if they have qualified IP income.[3]

Alternatively, a patent box may also be viewed as a metaphorical box: patents meeting stated criteria—that is, patents

that are ‘in the box’—receive a concessional tax rate for the income they generate.

What was proposed

in the Budget?

In the 2021–22 Budget, the Government

proposed its patent box tax regime would provide a 17% concessional tax rate

for corporate income derived directly from Australian medical and

biotechnology patents.[4]

Figure 1 below shows that the 17%

concessional tax rate of the proposed patent box is considerably lower than the

usual corporate tax rate (from 2021-22 onwards).

Figure 1: patent box’s concessional tax rate compared to

corporate income tax rate

Source: Parliamentary Library estimates based

on Australian Government, Budget Measures: Budget

Paper No. 2: 2021–22, 23; Australian Taxation

Office (ATO), ‘Changes to Company Tax Rates’, ATO website, 28 October 2021.

Why is the Government introducing a patent box?

R&D activities are widely perceived to have positive

benefits (known as ‘positive externalities’) that spill over to other parts of

the economy and benefit the rest of society. As such, many governments around

the world attempt to promote R&D activities through a combination of direct

investment and tax incentives.

Currently, over 20 countries have some form of patent or

IP box tax schemes.[5]

While patent box tax regimes can differ widely in their scope, they are mostly

designed to achieve some or all of the following objectives:

- promote

increased investment in R&D activities

- promote

the commercialisation of research

- prevent

the erosion of domestic tax base that can occur when mobile sources of income

are transferred to other countries.

The assumption underlying all three objectives is that IP

is highly mobile and companies that own IP can relocate these assets to

countries that provide favourable tax treatment.[6]

For example, when a company develops a patent in Australia, it can choose to

commercialise the patent by licencing the use of the patent to an Australian or

an overseas manufacturer.

Patent box tax regimes are typically intended to

incentivise companies to commercialise their patents ‘onshore’ in the host

country by providing concessional tax treatment, thus capturing at least some

taxes in the host country, rather than losing all income generated from patents

to an overseas country.

The OECD recommendations to tackle tax avoidance

Governments around the world have increasingly sought to

modify their tax regimes to incentivise the retention and acquisition of IP. This

competition between countries has resulted in ever more generous tax regimes

that enable multinational enterprises to access low tax rates for IP related income

without contributing significant amounts of R&D expenditures in the host

country.[7]

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) considers this type of competition to be a harmful tax practice.[8]

In other words, patent box tax regimes can potentially give rise to harmful tax

practices that will lead to ‘a race to the bottom’ if they are designed or

implemented poorly.

Consequently, the OECD/G20 BEPS (Base Erosion and

Profit Shifting) Project provides 15 action plans that equip governments

with instruments needed to tackle harmful tax avoidance behaviours.[9]

The Australian Government said it would follow the OECD’s

guidelines to ensure that its patent box regime meets internationally accepted

standards.[10]

In July 2021, the Treasury released a Discussion Paper

on the policy design of the Government’s proposed patent box.[11]

Details of the Australian patent box design are discussed below in the ‘Key issues and provisions’ section of this Digest.

Opening a ‘box’ of worms – is a patent box a good or bad idea?

The debate around the benefits of patent box tax

concessions is highly contested, with no consensus view emerging as to their overall

effectiveness. The following three questions are central to any debate on

patent box tax regimes:

- does

a patent box promote economic growth and innovation?

- do

potential benefits of a patent box outweigh its drawbacks?

- are

there better alternative policy tools to promote innovation?

In 2015, the Department of Industry, Innovation and

Science (DIIS) published a report titled Patent

Box Policies.[18]

The report found that a patent box in Australia should lead to an increase in

the number of patent applications. However, this increase would largely be the

result of ‘opportunistic’ behaviour and would not reflect a genuine increase in

inventiveness.[19]

As such, the report concluded:

patent boxes are not a very appropriate innovation policy

tool because they target the back end of the innovation process, where

market failures are less likely to occur.[20]

[emphasis added]

In 2016, the Joint

Select Committee on Trade and Investment Growth’s Inquiry into Australia’s

Future in Research and Innovation also cautioned:

If a patent box is introduced, it should be subject to a sunset

clause after three years of operation. A review should be undertaken to

determine the effectiveness of the patent box scheme and whether it should be

extended and for how long.[21]

[emphasis added]

The Bill does not contain a sunset clause as recommended

by the Joint Select Committee.

The conclusions reached by the 2015

DIIS report have been disputed by many industry stakeholders.[22]

Advocates of a patent box (for example, pharmaceutical companies) argue that the tax

regime will encourage companies to increase investment in R&D activities

and enable patents to be domiciled in the host country for tax purposes.[23]

Due to the increased investment in R&D activities, the

advocates argue that the lower tax rates introduced by a patent box regime will

eventually attract more patents and lead to economic growth.[24]

This type of argument is typically known as the ‘Laffer Curve

argument’ (sometimes criticised as ‘Voodoo Economics’),[25]

which has often been used to justify tax cut policies.[26]

Furthermore, the advocates believe that a patent box can

be more effective than R&D Tax Incentive programs in promoting the commercialisation

of research.[27]

They argue that Australia’s current R&D

Tax Incentive program is ‘input‐based’—that is, the program

encourages companies to invest in eligible R&D activities, and in return

the companies receive a tax benefit regardless of whether they decide to

commercialise their research in Australia.

In contrast, a patent box is an ‘output‐based’ measure

that provides a lower tax rate for corporate income generated from patents

filed and granted—that is, after the R&D has already occurred in Australia.[28]

If a patent is not commercialised and generates no income, then the patent

owner is unable to receive any tax benefit from the patent box’s concessional

rate. As such, the advocates believe a patent box regime will be effective to incentivise

companies to commercialise their patents onshore in Australia.

Evidence for and origins of the

proposed medical and biotechnology patent box regime

It is arguable that the Bill is a policy response to

sustained industry representations to the Government rather than a regulatory

response informed by a substantive body of generally accepted evidence.

As noted above, the lack of a firm and accepted evidence

base regarding the effects of patent box tax concessions has resulted in a lack

of a consensus view as to their overall effectiveness. This means that the

evidence for the need for a patent box regime is, at best, contested.

Despite the contested evidence, stakeholders in the

Australian medical and biotechnology sector have been advocating for such a

regime for many years. As noted in the Regulatory Impact Statement:

Certainly, [the medical and biotechnology] industry has

been the most active in advocating for a patent box with a competitive

concessional rate on eligible patents. This industry also has experience

with patent box regimes in other jurisdictions and has indicated it can comply

with the regulatory burden consistent with other foreign patent box regimes. For

the above reasons, in the 2021-22 Budget the Australian Government announced

its intention to introduce a patent box regime for the medical and

biotechnology sector, and that it would consult with industry on the design of

the patent box prior to making a final decision on the regime.[29]

[emphasis added]

Committee consideration

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

At the time of writing, the Committee has not considered

this Bill.[34]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Official position

At the time of writing, non-government parties and

independents have not made official comments on the Bill.

Media speculation

Kim Carr, a Labor Senator from Victoria, indicated in a

media article in May 2021 that he would not support the introduction of a

patent box regime. Senator Carr said:

The history of patent boxes in other countries suggests that

we should be wary of measures that increase the risk of lost revenue without

guarantees of compensatory increases in economic activity…

What patent boxes really do is create an incentive for

multinational companies to move their intellectual property around between

jurisdictions, which opens the possibility of rorting…

The Morrison

Government’s decision to take the patent-box option indicates its confusion

about innovation, and industry policy in general.[35] [emphasis added]

The Opposition has yet to make a comment on the Bill. As

such, it is not clear if the above remarks by Senator Carr reflect the current ALP

policy position in relation to the measures proposed by the Bill.

Position of

major interest groups

Medical and pharmaceutical industry

Medical and pharmaceutical industry associations are

supportive of the Bill. For example, Medical Technology Association of

Australia (MTAA) issued a press release:

MTAA has welcomed the introduction of the Government’s Patent

Box Bill into the House of Representatives this week, which aims to spur on

local medical technology innovation and investment into the future. The Patent

Box was first proposed and championed by MTAA in 2015, and since then has been

supported by a growing number of stakeholders across the MedTech [Medical

Technology] industry and wider health sector.[36]

Similarly, Medicines Australia, an industry association

representing members of the medical industry, said:

This legislation is a welcome first step, and we will

continue to encourage stronger and bolder incentives to promote and protect

Australian innovation. The proposed design of the patent box, tabled in

Parliament yesterday, could go further to attract multinational

biopharmaceutical companies to invest in developing or manufacturing medicines

and vaccines onshore. Australia still faces significant barriers, such as a

smaller population and remote geographical location to other jurisdictions. We

look forward to a continuing constructive partnership with the Government to

increase the competitiveness of the patent box.[37]

[emphasis added]

These industry associations are broadly supportive of

patent box, but they may have concerns or recommendations regarding specific

aspects of the regime. The specifics are discussed below in the ‘Key provisions

and issues’ section of this Digest.

Tax advocacy groups and academics

Some think-tanks and academics oppose the Government’s

proposed patent box regime because they believe it will lead to ‘tax lurk’. For

example, David Richardson, a Senior Research Fellow at the Australia Institute,

said:

If we genuinely want to promote Australian manufacturing in

the medical and biotech industries there are better mechanisms that might be

considered. Similarly if we want to encourage R&D there are much better mechanisms.

The patent box risks merely adding another tax lurk for multinationals in a

race to the bottom against other patent boxes in the UK and elsewhere.[38]

[emphasis added]

Dr Isaac Gross of Monash University argues:

In short, a patent box is good in theory but bad in practice;

and the design of the Australian government’s patent box is particularly bad. It

will likely end up being just another way multinational companies can avoid

paying tax.[39]

[emphasis added]

Tax Justice Network, an advocacy group calling for ‘tax

justice’ and ‘fairer’ tax systems, expressed several concerns regarding the

proposed patent box. The group said:

We are concerned that introducing the patent box regime for

the medical and biotechnology sectors will give away tax revenue for

activities corporations would have already carried out. Further, we are

concerned that once introduced, the patent box regime will be expanded over

time to reduce the tax contributions corporations need to make on revenue

derived from patents related to other business sectors. We are further

concerned about the complexity of ensuring the integrity of the claims made by

corporations against the lower tax rate in the patent box regime. As a result,

there will be an incentive for corporations to seek to claim as much of their

income as possible falls within the lower tax rate of the patent box.[40]

[emphasis added]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum (EM), the measure

introduced by the Bill is estimated to decrease the underlying cash balance by

$120 million over the forward estimate period.[41]

All figures in this table represent amounts in $million.[42]

| 2020–21 |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

2024–25 |

| 0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-50.0 |

-70.0 |

Statement of Compatibility

with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[43]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

At the time of writing, the Committee has not considered

this Bill.[44]

Structure of

the Bill

The Bill has one Schedule comprising three Parts:

- Part

1 is titled main amendments and amends the ITAA 1997 to introduce

a patent box regime

- Part

2 is titled other amendments and inserts definitions of key terms into

the ITAA 1997

- Part

3 sets out the application and transitional provisions for the patent

box regime in the Income Tax

(Transitional Provisions) Act 1997.

Key issues and provisions

Item 1 in Part 1 of the Bill inserts proposed

Division 357—Patent box into the ITAA 1997. Item 1 specifies the

eligibility criteria for the patent box regime (for example, who is eligible

for the patent box regime, what patents qualify for the regime).

Who is eligible for the patent box?

To be eligible to receive the concessional tax treatment

of the patent box regime, an entity must be defined as a ‘R&D entity’ as

per section 355-35 of the ITAA 1997, which applies to the existing R&D

Tax Incentive program. In other words, an eligible R&D entity for the

patent box must be a company that is a resident of Australia for income tax

purposes or a foreign resident operating through a permanent establishment in

Australia subject to a double tax agreement.[45]

It appears that the Government’s intention is for the

patent box to apply to companies only.[46]

However, by relying on the definition of R&D entity in section 355-35 of

the ITAA 1997, it means public trading trusts with a corporate trustee

may also be eligible for the patent box.[47]

It is unclear if this is intended by the Government.

Patentee vs licensee

Furthermore, only patentees who hold rights over a medical

or biotechnology patent will be eligible.[49]

An exclusive licensee of a patent does not satisfy this definition, as they

hold rights under the licence agreement as licensee, rather than rights under

the patent as patentee.[50]

What patents are eligible for the patent

box?

To be eligible, a medical or biotechnology patent must be

linked to a therapeutic good registered on the Australian

Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG).[53]

A medical or biotechnology patent qualifies if it is one of the following:

Only patents granted or issued after the Federal Budget

announcement on 11 May 2021 will be eligible for the patent box.[55]

The patent box regime will commence on 1 July 2022.[56]

For example, if an Australian company has:

- been

granted a medical patent on 12 May 2021 in the United States and

- the

patent is linked to a therapeutic good registered on the ARTG and

- the

company has made R&D expenditures linked to that patent in Australia[57]

and

- the

company derives income from the patent in Australia

then the company may be eligible to receive the concessional

tax treatment of the patent box regime from 1 July 2022 onwards.

Election for the patent box to apply

The patent box regime is optional, meaning a taxpayer must

‘elect’ or choose for the regime to apply. This election is irrevocable and

applies prospectively.[65]

The election must be made before or at the time the

taxpayer is required to lodge their income tax return for the relevant income

year.[66]

Practically speaking, this means Australian medical and biotechnology companies

should consider whether to opt into the patent box by the time their tax return

is due for the first applicable income year.

The EM clarifies that although it is not possible for a

taxpayer to make a patent box election that has retrospective effect, where

income is derived in an income year prior to the remaining conditions of the patent

box regime being satisfied (for example, milestone payments being received),

the taxpayer can later seek to amend their income tax return in order to claim

the tax concession in respect of that income once those conditions are

satisfied, provided they have made the required election on time.[67]

What income is concessionally taxed?

The Bill provides a 17% concessional tax

rate for the proportion of a patent box income stream that is

attributable to the taxpayer’s development of the patent that underlies that

income.[68]

What is a patent

box income stream?

A Patent box income stream is

defined in proposed subsection 357-25(3) of the ITAA 1997 as

assessable income derived from:

- sales

or rental income derived by the taxpayer from the sale or dealings of a

therapeutic good linked to the taxpayer’s eligible patent or patents

- royalties

or licence fees derived by the taxpayer for granting rights to exploit the

taxpayer’s eligible patent or patents

- a

balancing adjustment event derived from proceeds of sale received by the

taxpayer from the sale or assignment of the taxpayer’s eligible patent or

patents

- damages

or compensation payable to the taxpayer in respect of the taxpayer’s patent or

patents.[69]

Notably, income from manufacturing remains excluded from

the scope of the patent box.[70]

Figure 2 below shows only income

generated directly from patented products will be eligible for the patent

box. Income due to manufacturing, branding and other attributes of patented

products will not be eligible.

Figure 2: income derived directly from eligible patents can receive the 17%

concessional tax rate under the patent box

Source: Australian

Government, 2021–22 Budget’s Tax Factsheet, p. 3.

Steps for determining income

streams

Proposed subsection 357-25(1) of

the ITAA 1997 provides that taxpayers are required to identify a patent

box income stream in order to access the concessional tax treatment

provided by the proposed patent box regime. In other words, it is up to

corporate taxpayers to record and identify whether their income (for example,

royalties from a patent) meets the requirements set out in proposed section

357-25.

Under proposed subsection 357-25(1) a corporate

taxpayer seeking to access the patent box regime will need to work out the

portion of their assessable income attributable to eligible

patents by undertaking the following steps:

- Step

1: identify all eligible patents that underlie the patent box

income stream

- Step

2: determine a reasonable apportionment of the income arising from the patent

box income stream that is attributable to those patents by undertaking

a full transfer pricing analysis consistent with OECD principles

- Step

3: reduce that amount to reflect the extent of the taxpayer’s Australian

R&D activities, using an R&D fraction formula which is

consistent with the formula set down by the OECD in the BEPS Action 5 Report on

Harmful Tax Practices (see discussion about the ‘nexus approach’ below)[71]

- Step

4: multiple the result of step 3 by the patent box NANE fraction to

determine the amount deemed to be non-assessable and non-exempt income (‘NANE’

income) to achieve an effective tax rate of 17%.[72]

The relevant steps are discussed below.

Step 1: Identify eligible patents

The first step is for the taxpayer to identify all eligible

patents that underlie the patent box income stream. To be

eligible the patent must meet the requirements set out in proposed sections

357-15 and 357-20 discussed earlier in this Digest:

- it

must relate to a medical or biotechnology patent (issued in Australia, the

United States or European Union) granted or issued after the Federal Budget

announcement on 11 May 2021 and

- be

linked to a therapeutic good registered on the Australian

Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG).[73]

Step 2: determine the proportion of

the patent box income stream attributable to eligible patents

The second step is for the taxpayer to determine a

reasonable apportionment of the assessable income arising from the patent

box income stream attributable to the underlying patents by undertaking

a full transfer pricing analysis consistent with:

The EM notes:

Where the patent does not account for the entire value

received for the good, the income unrelated to the patent must be separated

from the income derived from the patent. A medical device may have an embedded

patent in the form of certain technology, but the value of that device may also

be attributable to the hardware, branding, marketing and other embedded patents

held by competitors and licenced by the taxpayer.

Where, for example, ordinary income derived from the sale of

therapeutic goods may be attributable to the marketing and manufacturing of

those therapeutic goods, as well as the underlying patent, it is only the

reasonable apportionment of this income attributable to the patent that is

intended to benefit from the patent box regime.

This reasonable apportionment approach requires the taxpayer

to identify the portion of the patent box income stream that is attributable to

the underlying patent in a manner that best achieves consistency with the

relevant OECD documentation outlined above.[75]

The EM provides two useful examples that show how a

company can determine a reasonable apportionment of its income from eligible

patents.[76]

Issue: compliance costs

The EM acknowledges that the patent box regime has high

ongoing compliance costs for companies wishing to receive the concessional tax

rate.[77]

As an analogy, when a person lodges their tax return, it is their

responsibility (rather than the ATO’s responsibility) to keep track of all the

receipts and this may be time consuming for the person. Steps 1 and 2

of in proposed subsection 357-25(1) will require careful record keeping

of patents and attribution of income to eligible patents.

However, the Regulatory Impact Statement notes that in

relation to the increased compliance costs:

these costs can be significantly reduced by leveraging some

of the compliance requirements businesses already incur to claim the R&DTI

[Tax Incentive] or meet the TGA requirements. Participation in the patent box

regime is optional, so firms whose costs are high relative to the benefits may

elect not to take advantage of the concession.[78]

Issue: transfer pricing

A large multinational company may have a manufacturing

division in one country, a research division in another country, and a

marketing division in a third country. These divisions of the same parent

company may sell services or products to each other. A company can charge a

higher price to its division in high-tax countries (reducing profits) while

charging a lower price (increasing profits) for its division in low-tax

countries.[79]

This is known as ‘transfer pricing’.

International sales between two subsidiaries or divisions of

the same parent company must be made using the ‘Arm’s

Length Principle’, meaning that the prices charged should be reasonable

market price, as if the two divisions were unrelated independent parties.[80]

The Arm’s Length principle is supported by all OECD countries (including

Australia).[81]

In the context of the Bill, the EM clarifies that when a

company identifies income that is derived from exploiting an eligible patented

invention, the portion of the income that is attributable to that patent

must be determined so as best to achieve consistency with OECD transfer pricing

principles.[82]

Put simply, a multinational company cannot illegally shift its profits between

its subsidiaries while also try to benefit from the concessional tax rate of

the patent box.

Step 3: determine the R&D

fraction for the income year

The third step is for the taxpayer to determine their

Australian R&D activities, using an R&D fraction formula

that gives effect to the ‘nexus approach’ recommended by the OECD in the BEPS

Action 5 Report on Harmful Tax Practices.

To give context to how the R&D fraction

for an income year is determined under the Bill, a brief summary of the OECD

‘nexus approach’ is provided below.

The OCED BEPS ‘nexus approach’

BEPS Action 5 Report

(OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Action Plan) recommends countries

adopt the modified nexus approach for patent box regimes to ensure that they do

not give rise to harmful tax practices.[85]

BEPS Action 5 is endorsed by all OECD and G20 countries (including Australia).[86]

Australia’s patent box regime will

comply with the nexus approach.[92]

Proposed subsections 357-25(1) and 357-30(1) of the ITAA 1997

specify that a taxpayer can only benefit from the concessional tax treatment of

the patent box if the taxpayer incurs ‘qualifying R&D expenditure’ of

eligible patents in Australia. Put simply, if a company does not undertake

R&D activities in Australia, then it would not be able to receive the lower

tax rate of the patent box.

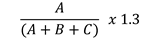

R&D fraction

Pursuant to the requirements of the nexus approach set out

above, taxpayers must keep track of how much R&D activity is undertaken in

Australia. Only R&D expenditure incurred for the purposes of actual R&D

activities (as defined in the R&D Tax Incentive program) in the development

of an eligible patent can constitute qualifying expenditure for the purposes of

the R&D fraction.[93]

Proposed subsection 357-30(1) provides a formula to work out the R&D

Fraction (that is the proportion of R&D activities eligible for the

patent box’s concessional rate). The higher the

fraction, the more patent box

income that may be taxed concessionally:

A = Total amounts of taxpayer’s notional deductions for

R&D expenditure in respect of a qualifying patent or patents.

B = Total expenditure incurred in respect of a qualifying

patent or patents on R&D activities conducted outside of Australia by one

or more associates of the R&D entity.

C = Total cost of each depreciating asset in respect of

which the taxpayer can deduct an amount under Division 40 for the income year

attributable to the qualifying patent or patents.[94]

The numerator ‘A’ in the R&D Fraction

captures only the R&D expenditure incurred by the taxpayer for R&D

activities undertaken in Australia.

For ‘C’ an integrity rule can apply to deem the cost of an

asset held by the R&D entity to be its market value if at the asset

acquisition time, the R&D entity was not dealing at arm’s length and the

asset’s cost was less than its market value.[95]

A 30% uplift is then applied to the fraction. The EM clarifies

that this uplift only applies to the extent that the numerator does not surpass

the denominator as the R&D Fraction is capped at one. The R&D

Fraction is cumulative, including all R&D expenditure from previous

years.[96]

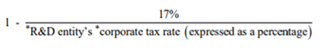

Step 4: determine deemed amount of NANE

income to achieve an effective tax rate of 17%

The fourth step is to determine the amount deemed to be

NANE income to achieve an effective tax rate of 17%.[99]

This is done by multiplying the R&D Fraction

(the result of step 3) by the patent box NANE fraction. The patent

box NANE fraction is determined by the formula in proposed

subsection 357-25(7):

The effect of this is to achieve an effective tax rate of 17% in respect of the

relevant income from the patent box income stream.[100]

Concluding comments

The Bill introduces a patent box regime that aims to incentivise

companies to commercialise their patents in Australia. The Bill appears to be a

policy response to sustained representations from industry, rather than a

regulatory response informed by a substantive body of generally accepted

evidence.

Nonetheless, the rather narrow measures (that focus on the

medical and biotechnology sector) proposed by the Bill complement the

Government’s announcements regarding an additional

$2 billion investment in the R&D Tax Incentive program[101]

and a $2.2 billion investment in the University

Research Commercialisation Action Plan,[102]

all of which may be viewed as part of the Government’s broader efforts to boost

innovation.

The proposed patent box regime is wider in scope than what

was announced in the 2021‑22 Budget (for example, the regime will apply

to patents granted in the US and Europe). The regime may expand further in the

future to include Australia’s clean energy sector and other industries.

Given there are diverging views on the effectiveness of

patent boxes, potential points of contention regarding the Bill include:

- Should Australia introduce a patent box?

- Is the 17% concessional tax rate a suitable rate?

-

Should the scope of the patent box be amended to apply more broadly?